Abstract

Historic migration and the ever–increasing current migration into Western countries have greatly changed the ethnic and cultural patterns of patient populations. Because health care beliefs of minority groups may follow their religion and country of origin, inevitable conflict can arise with decision making at the end of life. The principles of truth telling and patient autonomy are embedded in the framework of Anglo–American medical ethics. In contrast, in many parts of the world, the cultural norm is protection of the patient from the truth, decision making by the family, and a tradition of familial piety, where it is dishonorable not to do as much as possible for parents. The challenge for health care professionals is to understand how culture has enormous potential to influence patients’ responses to medical issues, such as healing and suffering, as well as the physician-patient relationship. Our paper provides a framework of communication strategies that enhance crosscultural competency within nephrology teams. Shared decision making also enables clinicians to be culturally competent communicators by providing a model where clinicians and patients jointly consider best clinical evidence in light of a patient’s specific health characteristics and values when choosing health care. The development of decision aids to include cultural awareness could avoid conflict proactively, more productively address it when it occurs, and enable decision making within the framework of the patient and family cultural beliefs.

Keywords: end of life, advanced kidney disease, decision-making, Communication, Cultural Competency, Decision Support Techniques, Ethics, Medical, Ethnic Groups, Humans, Minority Groups, chronic kidney disease, Physician-Patient Relations

Introduction

This Moving Points in Nephrology describes the principles and challenges of providing person-centered care for patients with advanced kidney disease at the end of life. Communication between the practitioner and the patient (including their wider family/social support) is key to achieving these aims. As discussed by Davison and Jassal (1), this includes sharing prognosis, determining symptoms, and providing care aligned to the preferences and goals of the individual patient. These principles of truth telling and patient autonomy are embedded in the framework of Anglo–American medical ethics. In contrast, in many parts of the world, medical practice is on the basis of family decision making and medical beneficence. These differences can inevitably lead to conflict between patients, families, and clinicians and therefore, the need to develop strategies to reduce crosscultural miscommunication (2). This paper aims to help clinicians become culturally aware and competent, thereby improving their communication with patients and families.

The American clinical practice guidelines on dialysis initiation and withdrawal from the Renal Physicians Association (RPA) (2) state that “they reflect the ethical principle of respect for autonomy because clinicians, family members, and others have an ethical duty to accept the decisions regarding medically indicated treatment made by competent patients and in the absence of competence, to formulate decisions that would respect patients’ wishes, or if wishes are unknown, advance the best interest of their patients” (2). Historic migration and the ever–increasing current migration into Western countries have, however, greatly changed the ethnic and cultural patterns of patient populations. This is particularly true when considering advanced kidney disease, which is much more common in many ethnic groups compared with white European populations (3). As an example, around 50% of patients on RRT in London are from ethnic minorities, predominantly South Asian and Afro-Caribbean (4).

Migration: Magnitude of the Issue

Throughout human history, individuals, families, and groups have emigrated from their native homes to other places globally for many reasons: the prospect of education, economic, or social advantage; the need to escape war, political torture, or other conflicts; or the desire to reunite with other family members. At one point in 2005, there were an estimated 191 million immigrants across the globe: approximately 64 million of these immigrants arrived in Europe, and 44 million arrived in North America, a tripling of the immigrant populations in these regions compared with 20 years earlier (5). Spain, Germany, and the United Kingdom were the European countries with the highest immigration, receiving more than one half of all immigrants in 2008 (6). Increasing diversity is a reality as witnessed by the daily news bulletins about dramatic increases in global economic and political migration. This means that there is an enlarging proportion of people who do not live in their own native country or culture.

In many parts of the world, the cultural norm is protection of the patient from the truth, decision making by the family, and a tradition of familial piety, where it is dishonorable not to do as much as possible for parents (7); examples are given in Table 1. With evidence that the ethics of minority groups may follow their religion and country of origin (8), conflict with Anglo–American medical ethics structure may arise from both patients’ and physicians’ perspectives, because both have their own languages, explanatory illness models, religious beliefs, and ways of understanding the experience of suffering and dying (9,10).

Table 1.

Examples of ethics of truth telling related to culture and country

| Country/Cultural Group | Attitudes toward Truth Telling |

| China | When fatal diagnosis or prognosis is given, the physician informs the family and hides it from the patient—it is up to the family to decide whether, when, and how to disclose the truth to the patient; families usually decide to conceal such information, and physicians are willing to follow such decisions and cooperate with families in deceiving patients (39) |

| Black | Only God has knowledge and power over life and death, and physicians cannot have access to this type of knowledge; the Christian religious view held by many in the black community holds that suffering is redemptive—it is to be endured rather than avoided; forgoing life support to avoid pain and suffering, therefore, might be seen as failing a test of faith (9) |

| Italy | Trend of partial and nondisclosure persists; this arises within families independent of patient requests, although there is some evidence that physician preferences are moving toward full disclosure (40) |

| Spain | Tradition of partial and nondisclosure; the majority of doctors state that they would inform the patient only in certain circumstances or if requested by the patient (40) |

| India (Hindu) | Tradition of nondisclosure and relatives protecting the individual from knowledge in case he/she gives up hope and dies prematurely; this is exacerbated by the belief that modern medicine often provides hope, however unrealistic, that a cure is possible (41) |

The Effect of Diversity on ESRD and at the End of Life

Culture is but one of several typologies of difference that have been used to signify diversity among individuals and groups. Narrowly defined from an anthropologic perspective, culture can be thought of as that which refers to the “…patterns, explicit and implicit, of and for behavior acquired and transmitted by symbols,” language, and rituals (7). Seen as a recipe for living in the world, this conceptual framework for culture explains the means of transmitting these recipes to the next generation (8). The challenge for health care professionals in an increasingly diverse society is to understand how culture has enormous potential to influence patients’ responses to medical issues, such as healing and suffering, as well as the physician-patient relationship. As a direct result, those from migrant communities may possess little knowledge of or have little exposure to palliative care. (Palliative care has been defined as an approach that improves the quality of life of patients [adults and children] and their families who are facing problems associated with a life-threatening illness. It prevents and relieves suffering through the early identification, correct assessment, and treatment of pain and other problems, whether physical, psychosocial, or spiritual. Addressing suffering involves taking care of issues beyond physical symptoms. Palliative care uses a team approach to support patients and their caregivers. This includes addressing practical needs and providing bereavement counselling. It offers a support system to help patients live as actively as possible until death [11].) For example, in the United Kingdom (12) and more recently, among people living with end stage kidney failure in Canada (13), those from black, Asian, or minority ethnic groups were identified as being statistically less likely, after taking all other factors in account, to understand the value of palliative care. Specific to kidney disease, the US Renal Data System data show that rates of dialysis withdrawal in minority ethnic groups are lower compared with in the white population (14). It is also important to note that migrant communities may also have different cultural values regarding life and death compared with the Western approach to dying, which includes palliative care.

Identifying preferences for medical care in advance of untoward or terminal circumstances can be a difficult and emotional process. The decision-making model of advance care planning derived from bioethics practices assumes that choices made by the individual can be arrived at through rational processes that are unchanged by time, shifting social consequences, or disease and illness progression. Such a model may only appeal to certain subsets of groups, thus limiting the utility of instruments used for advance planning (living wills or durable powers of attorney for health care) (15,16). For some groups, speaking about the dying process or planning for death may represent a transgression of a strong cultural taboo and could create additional distress. Other patients, unfamiliar with or mistrustful of the legal system, may misconstrue the purpose or nature of formal advance care planning documents. In all cases, rather than abandon the goals of advance care planning, strategies should be sought that facilitate understanding. For example, a generic discussion to identify a health care proxy need not be cast as a discussion of death but rather, can be an opportunity to determine desired roles of various family members and support persons. Discussions about patient preferences for end of life care should be culturally and linguistically appropriate and reflect sensitivity to patient values and beliefs.

Relevant knowledge and greater awareness of palliative care are, therefore, critical, particularly as growing evidence suggests that a significant number of people from ethnic communities, which disproportionately include those on low incomes, misses out on high–quality palliative care and end of life care. This situation exists even in the United Kingdom, despite palliative care being free at the point of delivery from the National Health Service and the independent charitable sector. Possible explanations for these disparities include (1) different referral patterns to specialist palliative care and lack of understanding among professionals about exactly which patients to refer and when; (2) gate keeping by services; (3) complex linguistic and communication barriers; (4) different preferences, including for more aggressive or curative care at the end of life, or a cultural mistrust of end of life care; and (5) strong religious and familial support systems (17–19). Additionally, people from minority ethnic communities may also experience overt and inadvertent racial discrimination at individual and institutional levels (20). Identifying and eliminating vertical health inequality (inequality among households or individuals) and horizontal health inequality (inequality among culturally defined [or constructed] groups) in the delivery of high–quality palliative and related care, therefore, represent critical mandates. More sophisticated standards for monitoring and ensuring the cultural sensitivity and cultural competency within the palliative medicine workforce and more widely should be used along with strategies to increase community-based partnerships.

Avoiding and Coping with Conflict

Both the US RPA guidelines (3) and the General Medical Council (GMC) (21) in the United Kingdom give some guidance about avoiding conflict. Both are on the basis of the premise that individual patients should be aware of their prognosis to make decisions regarding their care. The GMC states clearly that physicians do not have to provide treatment that they consider nonbeneficial and that information should not be given to a patient only if he/she refuses (and has capacity to do so), not because of the request of the family unless it is believed that giving information would cause the patient serious harm (defined in document to mean “more than that the patient might become upset or decide to refuse treatment” [21]). The GMC also suggests that, where there is conflict with patient/family wishes or other medical colleague decisions, options are to consider seeking advice from a more experienced, perhaps senior, colleague, obtaining a second opinion, or holding a case conference. Ultimately, seeking legal advice and resorting to the United Kingdom courts as final arbiter may be required, but awareness of cultural differences during patient/family discussions and guidance related to potential ethical conflicts should avoid this route (22).

In contrast, the US RPA guidelines are dialysis specific. They also address the issue of conflict between clinicians and patients/families regarding demands for dialysis that the clinician deems medically inappropriate. The cultural conflict of giving information (or not) to individual patients is not addressed. The suggested solutions to conflict are specifically a trial of dialysis (but this needs clear end points), second opinions, consultation with the hospital ethics committee or ethics consultants, and ultimately, potential transfer to another institution or physician to provide dialysis. If none are willing to accept the patient, the family/legal representative can be informed that dialysis will be withdrawn unless there is a court injunction to the contrary.

In reality, neither the United Kingdom GMC nor the US RPA guidelines avoid conflict. Nephrology teams, therefore, need to develop cultural awareness and crosscultural communication strategies, including use of decision aids, to enable shared decision making within the framework of the patient and family cultural beliefs. This approach should proactively reduce conflict (23) and productively address it when it occurs.

Crosscultural Communication Strategies

Culture defines the way that people make sense of the world and influences how individuals view the illness experience and approach decision making. Despite the importance of culture in health care, traditional medical training is deficient in crosscultural communication education. Strategies to improve skills and knowledge in cultural competence and better communication relevant to the care are required (24). For example, crosscultural communication includes strategies that acknowledge individual cultural traditions, avoid generalizing a patient’s beliefs or values on the basis of cultural norms, and take into account one’s own beliefs, values, and experiences (25). Clinician culture is multifaceted and largely shaped by the biomedical influences, which include the knowledge and experience that accompany becoming a physician as well as the influence of a given health care system in which one practices (9). A recent qualitative study of United States and United Kingdom academic medical centers examined the influence of institutional culture on do not resuscitate decision making at end of life (26). The way that the physicians in training approached decision making was directly influenced by whether the hospital policies prioritized patient autonomy versus best interest. For instance, physicians training in a hospital that prioritized autonomy would be more likely to neutrally offer resuscitation, regardless of whether they believed resuscitation to be clinically appropriate.

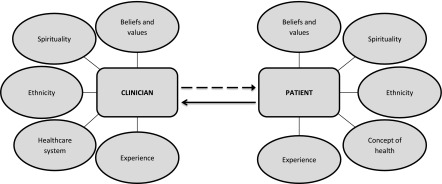

To address these challenges, crosscultural communication strategies must be reflective and individualized (23,27). The first step to crosscultural competency involves becoming aware of the inherent beliefs, values, and biases within ourselves as clinicians and the influence of the health care system in which one practices. When clinicians become conscious of their own beliefs and values, they may become more receptive and open to those of the patients, especially when differences exist. Figure 1 visualizes the complex cultural influences within the patient and clinician relationship.

Figure 1.

Cultural aspects that influence the clinician-patient interaction. When clinicians become conscious of their own beliefs and values, they may become more receptive and open to those of the patients, especially when differences exist.

The second step involves effective communication strategies that are evocative, nonjudgmental, and respectful. Kagawa-Singer and Kassim-Lakha (23) have proposed a strategy to elicit information about the patient's Resources, Identity, Skills and Knowledge (RISK), known as the RISK reduction assessment. This is a helpful strategy to learn and support the particular cultural influence and beliefs of a given patient and family. The RISK reduction assessment includes resources for patients and families to navigate the health care system, individual circumstances and migration experience, skills available to the patient and family to navigate the health care system and cope with the disease itself, and knowledge about the ethnic groups health beliefs, values, practices, and cultural communication etiquette (23). Teal and Street (27) developed a culturally competent communication model from existing models that incorporate critical elements of cultural communication. This model highlights five key communication skill sets: nonverbal skill, verbal skill, recognition of potential cultural differences, incorporation of and adaptation of cultural knowledge, and negotiation/collaboration (28).

Ask-tell-ask is a helpful communication strategy to engage in culturally competent communication (29). This framework encourages a two-way conversation, in which the clinician first asks for the patient’s and/or family’s input rather than reflexively disclosing information. The usefulness of this strategy extends beyond giving information to include asking about cultural experience, decision-making preferences, and prior experiences with health care and exploring values and preferences. Table 2 includes examples of open-ended questions to better understand the cultural preferences and values of a given patient and family (23,28,29).

Table 2.

| Communication Task and Communication Strategy | Example |

| Understand the patient’s experience | |

| Rapport building/ask about the patient as a person | Can you tell me about your life? Where were you born and raised? How has your experience been coming to a new country? |

| Invite curiosity | As your clinician, what would be helpful for me to know about you and your life? |

| Assess how the patient interprets her condition | What do you think has caused your kidney problems? |

| Giving information | |

| Assess for health knowledge needs | What is your understanding of your condition? |

| Ask what kinds of information desired | Some people want to know everything about their medical condition, whereas others may not. Do you have a preference? |

| Give information concisely without medical jargon and check in for understanding | To ensure that I did a good job in giving you information, can you tell me what you will take away from this visit? |

| Determine patient involvement in medical decision making | |

| Assess decision-making preferences | How would you like decisions to be made about your health care? |

| Determine the patient’s preferred decision maker | Who is the person that you trust to help make medical decisions if you were unable to do so? |

| Understand the patients beliefs and values | |

| Ask about what is important to the patient and loved ones | As we talk about how best to care for you, what you are hoping for? What concerns you most? |

| Address spiritual concerns | Faith can be a source of strength. Can you tell me about your faith? |

| Address trust concerns | |

| Be transparent; avoid judgement and defensiveness | Some people are uncomfortable discussing their health with a clinician from a different background. Please feel comfortable sharing with me your concerns |

| Explore experience | When it comes to your health, have you ever felt that you have been treated unfairly? |

| Address resource/needs | |

| Actively inquire about ways to support the patient and family | What kinds of support would be helpful to you and your family? |

| Actively assess for concerns about the plan | What concerns do you have about this plan? |

After the clinician has an understanding of the kinds of information desired and ways to communicate this information, how the information is told is equally important. Patients and families may have language barriers and low health literacy, further complicating their ability to process and act on critical medical information (30). Clinicians should use clear language, with only one to three pieces of information without medical jargon. The final ask allows the patient and family to teach back what they have heard to ensure that the clinician gave information in a way that was easily understood: “To ensure that I did a good job giving you information, can you tell me what you will take away from our discussion today?” This question is nonjudgmental and invites the opportunity for the patient and family to correct information or perceptions that the clinician may have shared. Additionally, this final ask invites the patient and family to share any concerns or lingering questions.

Shared Decision Making

Shared decision making is seen as useful in enabling practitioners to be culturally competent communicators (28) by providing a model where clinicians and patients jointly consider best clinical evidence in light of a patient’s specific health characteristics and values when choosing health care (31). It is important to recognize that some patients would rather have different levels of engagement in the decision-making process, with some preferring a recommendation from the clinician (28). In practice, it requires patients, professionals, and health care systems to think differently about the delivery of and engagement with evidence-based care. Both practitioner and patient are expected to collaborate proactively in this decision-making process by exchanging information about the illness, diagnosis, and treatment from their areas of expertise; making explicit values and preferences in the context of care pathways and/or lifestyle; reasoning together the best option for the patient; and agreeing and implementing the choice that aligns best with clinical evidence and patient preference (32).

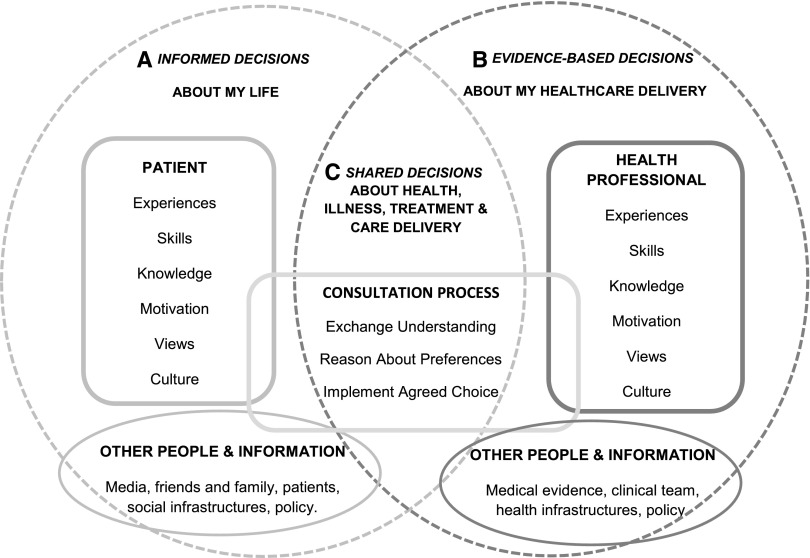

Patients, professionals, and health care infrastructures can be enabled to engage in shared decision making (31,33). Interventions enabling people to collaborate more effectively within this complex system are informed by findings from the applied social sciences, medical communication, evidence-based practice, and health professional training. Different types of interventions are used to support people in different stages of making a decision and reasoning with others (33): for example, evidence-based prompts for professionals to make accurate choices in the context of care pathways and patients to make informed decisions in the context of their lives (1 and 2 in Figure 2); health professional training, patient decision coaching, and consultation prompts for more effective communication between patients and professionals (3 in Figure 2); and training and decision aids for others involved in implementing care in people’s lives (e.g., other health professionals and/or family) (Figure 2). When developed using systematic methods to identify patient, professionals, and health care needs and preferences, these resources are culturally relevant (34), because they make explicit the options, attributes, values, and evidence of importance to all people involved in making and implementing health care choices (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Using such a decision support system is culturally relevant as it makes explicit the options, attributes, values, and evidence of importance to all people involved in making and implementing health care choices. Function–informed, evidence–based, and shared decision support for (A) the patient, (B) the professional, and (C) the consultation. Reprinted from Breckenridge et al. (33), with permission.

Evaluation of shared decision–making interventions within predialysis education programs suggests that they are acceptable to staff and patients and can be implemented across different health care systems: for example, shared decision–making training and prompts for use by health professionals to structure predialysis education consultations (35) and patient decision aids supporting patients’ engagement with predialysis programs (36). Furthermore, there is a range of patient-centered approaches used by others in the delivery of self-care, advance care planning, and palliative services that provide techniques (e.g., goal setting training) and prompts (e.g., patient–reported outcome measures) to help professionals deliver and negotiate evidence-based care in a culturally appropriate way (37,38).

Conclusions

There is increasing awareness in both lay and medical circles that, for many patients, modern medicine fails to achieve the quality and dignity of death that most people would want when asked. To achieve this, it is essential to enhance communication between health care teams, patients, and families. The framework for doing this has mostly been developed around the Anglo-American model of truth telling and patient autonomy as essential components of the decision-making process. Many of our patients and families make decisions using different frameworks, and this may be further exacerbated by an underlying distrust of health care teams delivering care in culturally and linguistically different ways. The resulting conflict often disadvantages the individual patients concerned with failure to share prognosis, wishes, and goals. Increasing crosscultural competency with resulting enhanced use of shared decision making should avoid some of this conflict and improve the quality of medical care for patients throughout the continuum of their illness.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

The research of S.N.D. is funded by Canadian Institutes of Health Research grants 89801, 126151, and 126193 and Alberta Innovates Health Solutions grant 201400400.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.Davison SN, Jassal SV: Supportive care: Integration of patient-centered kidney care to manage symptoms and geriatric syndromes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 1882–1891, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Renal Physicians Association: Shared Decision-Making in the Appropriate Initiation of and Withdrawal from Dialysis Clinical Practice Guideline, 2nd Ed., Rockville, MD, Renal Physicians Association, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patzer RE, McClellan WM: Influence of race, ethnicity and socioeconomic status on kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol 8: 533–541, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.UK Renal Registry: 17th Annual Report: Chapter 1 UK Renal Replacement Therapy Incidence in 2013: National and Centre-Specific Analyses. Available at: https://www.renalreg.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/01-Chap-01.pdf. Accessed August 24, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Collett E: Europe: A New Continent of Immigration, Brussels, Belgium, European Policy Centre, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 6.EUROSTAT: Demography Report 2010. Older, More Numerous and Diverse Europeans, Luxembourg, Luxembourg, Publications Office of the European Union, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Pentheny O’Kelly C, Urch C, Brown EA: The impact of culture and religion on truth telling at the end of life. Nephrol Dial Transplant 26: 3838–3842, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson MRD: End of life care in ethnic minorities. BMJ 338: a2989, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kagawa-Singer M, Blackhall LJ: Negotiating cross-cultural issues at the end of life: “You got to go where he lives.” JAMA 286: 2993–3001, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phipps E, True G, Harris D, Chong U, Tester W, Chavin SI, Braitman LE: Approaching the end of life: Attitudes, preferences, and behaviors of African-American and white patients and their family caregivers. J Clin Oncol 21: 549–554, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization: Palliative Care—Fact Sheet No. 402, Geneva, Switzerland, World Health Organization, 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koffman J, Burke G, Dias A, Raval B, Byrne J, Gonzales J, Daniels C: Demographic factors and awareness of palliative care and related services. Palliat Med 21: 145–153, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davison SN, Jhangri GS, Koffman J: Knowledge of and attitudes towards palliative care and hospice services among patients with advanced chronic kidney disease. BMJ Support Palliat Care 6: 66–74, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thomas BA, Rodriguez RA, Boyko EJ, Robinson-Cohen C, Fitzpatrick AL, O’Hare AM: Geographic variation in black-white differences in end-of-life care for patients with ESRD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 1171–1178, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koffman J, Morgan M, Edmonds P, Speck P, Higginson IJ: “I know he controls cancer”: The meanings of religion among Black Caribbean and White British patients with advanced cancer. Soc Sci Med 67: 780–789, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crawley L, Koffman J: Cultural aspects of palliative medicine. In: Oxford Textbook of Palliative Medicine, edited by Cherny N, Fallon M, Kaasa S, Portenoy RK, Currow DC, Oxford, United Kingdom, Oxford University Press, 2015, pp 84–93 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahmed N, Bestall JC, Ahmedzai SH, Payne SA, Clark D, Noble B: Systematic review of the problems and issues of accessing specialist palliative care by patients, carers and health and social care professionals. Palliat Med 18: 525–542, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hopp FP, Duffy SA: Racial variations in end-of-life care. J Am Geriatr Soc 48: 658–663, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koffman J, Morgan M, Edmonds P, Speck P, Higginson IJ: ‘The greatest thing in the world is the family’: The meaning of social support among black Caribbean and white British patients living with advanced cancer. Psychooncology 21: 400–408, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arora S, Coker N, Gillam S: Racial discimination and health services. In: Racism in Medicine, edited by Coker N, London, King's Fund, 2001, pp 141–167 [Google Scholar]

- 21.General Medical Council: Treatment and Care towards the End of Life: Good Practice in Decision Making, 2010. Available at: http://www.gmc-uk.org/static/documents/content/Treatment_and_care_towards_the_end_of_life_-_English_1015.pdf. Accessed December 20, 2015

- 22.Crawley LM, Marshall PA, Lo B, Koenig BA; End-of-Life Care Consensus Panel: Strategies for culturally effective end-of-life care. Ann Intern Med 136: 673–679, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kagawa-Singer M, Kassim-Lakha S: A strategy to reduce cross-cultural miscommunication and increase the likelihood of improving health outcomes. Acad Med 78: 577–587, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Surbone A: Cultural aspects of communication in cancer care. Support Care Cancer 16: 235–240, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dzeng E, Colaianni A, Roland M, Chander G, Smith TJ, Kelly MP, Barclay S, Levine D: Influence of institutional culture and policies on do-not-resuscitate decision making at the end of life. JAMA Intern Med 175: 812–819, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Searight HR, Gafford J: Cultural diversity at the end of life: Issues and guidelines for family physicians. Am Fam Physician 71: 515–522, 2005 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Teal CR, Street RL: Critical elements of culturally competent communication in the medical encounter: A review and model. Soc Sci Med 68: 533–543, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schell JO, Arnold RM: NephroTalk: Communication tools to enhance patient-centered care. Semin Dial 25: 611–616, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dageforde LA, Cavanaugh KL: Health literacy: Emerging evidence and applications in kidney disease care. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 20: 311–319, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stacey D, Légaré F, Col NF, Bennett CL, Barry MJ, Eden KB, Holmes-Rovner M, Llewellyn-Thomas H, Lyddiatt A, Thomson R, Trevena L, Wu JH: Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 9: CD001431, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T: Shared decision-making in the medical encounter: What does it mean? (or it takes at least two to tango). Soc Sci Med 44: 681–692, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ahmad N, Ellins J, Krelle H, Lawrie M: Person-Centred Care: From Ideas to Action (Bringing Together the Evidence on Shared Decision Making and Self-Management Support), United Kingdom, The Health Foundation, 2014. Available at: http://www.health.org.uk/sites/default/files/PersonCentredCareMadeSimple.pdf. Accessed June 21, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Breckenridge K, Bekker HL, van der Veer SN, Gibbons E, Abbott D, Briançon S, Cullen R, Garneata L, Jager KJ, Lønning K, Metcalfe W, Morton R, Murtagh FM, Prutz K, Robertson S, Rychlik I, Schon S, Sharp L, Speyer E, Tentori F, Caskey FJ: How to routinely collect data on patient-reported outcome and experience measures in renal registries in Europe: An expert consensus meeting. Nephrol Dial Transplant 30: 1605–1614, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alden DL, Friend J, Schapira M, Stiggelbout A: Cultural targeting and tailoring of shared decision making technology: A theoretical framework for improving the effectiveness of patient decision aids in culturally diverse groups. Soc Sci Med 105: 1–8, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fortnum D, Smolonogov T, Walker R, Kairaitis L, Pugh D: ‘My kidneys, my choice, decision aid’: Supporting shared decision making. J Ren Care 41: 81–87, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Winterbottom AE, Gavaruzzi T, Mooney A, Wilkie M, Davies SJ, Crane D, Baxter P, Meads DM, Bekker HL, Mathers N, Tupling K: Patient acceptability of the Yorkshire Dialysis Decision Aid (YoDDA) Booklet: A prospective non-randomized comparison study across 6 predialysis services [published online ahead of print October 1, 2015]. Perit Dial Int doi:pdi.2014.00274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Walczak A, Butow PN, Bu S, Clayton JM: A systematic review of evidence for end-of-life communication interventions: Who do they target, how are they structured and do they work? Patient Educ Couns 99: 3–16, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Etkind SN, Daveson BA, Kwok W, Witt J, Bausewein C, Higginson IJ, Murtagh FEM: Capture, transfer, and feedback of patient-centered outcomes data in palliative care populations: Does it make a difference? A systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage 49: 611–624, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fan R, Li B: Truth telling in medicine: The Confucian view. J Med Philos 29: 179–193, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gysels M, Evans N, Meñaca A, Andrew E, Toscani F, Finetti S, Pasman HR, Higginson I, Harding R, Pool R; Project PRISMA: Culture and end of life care: A scoping exercise in seven European countries. PLoS One 7: e34188, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Firth S: End-of-life: A Hindu view. Lancet 366: 682–686, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]