Abstract

Both β1- and β3-adrenergic receptors (β1ARs and β3ARs) are present on nuclear membranes in adult ventricular myocytes. These nuclear-localized receptors are functional with respect to ligand binding and effector activation. In isolated cardiac nuclei, the non-selective βAR agonist isoproterenol stimulated de novo RNA synthesis measured using assays of transcription initiation (Boivin et al., 2006 Cardiovasc Res. 71:69–78). In contrast, stimulation of endothelin receptors, another G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) that localizes to the nuclear membrane, resulted in decreased RNA synthesis. To investigate the signalling pathway(s) involved in GPCR-mediated regulation of RNA synthesis, nuclei were isolated from intact adult rat hearts and treated with receptor agonists in the presence or absence of inhibitors of different mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and PI3K/PKB pathways. Components of p38, JNK, and ERK1/2 MAP kinase cascades as well as PKB were detected in nuclear preparations. Inhibition of PKB with triciribine, in the presence of isoproterenol, converted the activation of the βAR from stimulatory to inhibitory with regards to RNA synthesis, while ERK1/2, JNK and p38 inhibition reduced both basal and isoproterenol-stimulated activity. Analysis by qPCR indicated an increase in the expression of 18 S rRNA following isoproterenol treatment and a decrease in NFκB mRNA. Further qPCR experiments revealed that isoproterenol treatment also reduced the expression of several other genes involved in the activation of NFκB, while ERK1/2 and PKB inhibition substantially reversed this effect. Our results suggest that GPCRs on the nuclear membrane regulate nuclear functions such as gene expression and this process is modulated by activation/inhibition of downstream protein kinases within the nucleus.

Keywords: Beta-adrenergic receptor, Endothelin receptor, Nuclear membrane, G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR), Transcription, Signal transduction, Protein kinase

1. Introduction

β-adrenergic receptors (βARs) are part of the GPCR superfamily that signal through heterotrimeric G proteins. GPCRs activate a wide range of downstream effectors and regulate diverse cellular functions in cardiomyocytes, including contractility, metabolism and gene expression. Additionally, the downstream signalling pathways activated following ligand binding can vary depending on the composition of heterotrimeric G proteins, and particularly which α subunits interact with the receptor.

In mammalian cardiomyocytes, all three known βAR subtypes have been detected. β1ARs are the predominant subtype found in the heart, representing roughly 70% of the total βAR density [1]. Primarily involved in the regulation of cardiomyocyte contractility, β1ARs are known to signal through Gαs and adenylyl cyclase (AC). β2ARs, representing roughly 30% of the total βAR density, are also involved in the regulation of the contractility, but to a lesser extent [2]. β1ARs and β2ARs signal through Gαs and AC with similar efficacy. However, the signals are compartmentalized differently in cardiomyocytes, possibly due to their localization in distinct membrane microdomains and/or dual coupling of the β2AR to Gαs and Gαi [3]. β2ARs also have a high level of spontaneous activity not detected for β1AR [4]. During the development of heart failure, β1ARs are internalized, their synthesis is reduced, and they begin to signal predominantly through a Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CAMKII)-dependent mechanism, while β2ARs switch from Gαs to Gαi signalling, potentially activating cardioprotective mechanisms [2]. Additionally, expression and activity of GRK2 (βARK1), the primary GPCR kinase (GRK) in the heart, is increased during the development of heart failure, providing a molecular mechanism for βAR desensitization in heart failure [1]. While β3ARs are also expressed in healthy cardiomyocytes, their functions remain ill-defined, and they represent a negligible part of the total βAR density [1]. In fact, as opposed to the β1ARs and β2ARs, β3ARs appear to have negative inotropic effects and are actually up-regulated in response to heart failure [5]. Hence, βAR subtypes likely play non-redundant roles within the cardiomyocyte.

Recently, evidence has accrued showing that functional GPCRs are not solely localized at the plasma membrane but can also signal from different endogenous membrane compartments, including the nuclear membrane (reviewed in [6]). Recent evidence also seems to indicate that these intracellular receptors may have the capacity to regulate signalling pathways that differ from those of their plasma membrane counterparts, as was recently demonstrated for the metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 (mGluR5) [7]. In the case of the βARs, functional β1AR and β3AR, but not the β2AR, have been detected at the level of the nuclear membrane in rat and mouse adult ventricular myocytes [8]. Moreover, several studies have demonstrated that a number of their normal cell surface interactors, including Gαs, Gαi, Gαq, adenylyl cyclase, and PKA, as well as other regulatory molecules known to interact with GPCRs, are also associated with the nucleus or the nuclear membrane [9,10]. In fact, literature even seems to support the existence of nuclear-localized phosphoinositide signalling pathways that can regulate nuclear PKB/Akt signalling [11]. Furthermore, βARs on the nuclear membrane have been shown to be functional with respect to both ligand binding and effector activation [8]. Indeed, in isolated nuclei, β1ARs activate AC following treatment with isoproterenol, while β3ARs appear to stimulate de novo transcription, through Gαi activation [8]. However, the post-receptor signalling pathways that become activated following ligand binding and lead to changes in gene transcription remain to be identified.

Given the presence of GPCRs at the level of the nuclear membrane, we wished to assess what role they might play in adult cardiomyocytes, and to determine what pathways might be activated downstream of nuclear receptor activation and lead to modulation of gene transcription. To this end we used a pharmacological approach to investigate the involvement of different MAPKs and the PI3K/PKB pathway.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Materials

Anti-PKB, anti-phospho-PKB (threonine 308 and serine 473), anti-phospho-ERK p44/42 (threonine 202/tyrosine 204), anti-MEK1/2 and anti-phospho-MEK1/2, anti-p38 and anti-JNK2 antibodies were from Cell Signaling Technology. Anti-Raf1 and Lamin B antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Anti-NFκB antibody was from eBioscience. Horseradish peroxide (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies were from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories (West Grove, PA). Enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) reagent Renaissance Plus was from Perkin Elmer Life Sciences (Woodbridge, Ontario). Triton X-100 (TX-100), leupeptin, PMSF and DNase I were from Roche Applied Science (Laval, Quebec). SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis reagents, Bradford Protein Assay reagent, and nitrocellulose (0.22 μm) were from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Mississauga, Ontario). Isoproterenol was from Tocris Bioscience (Ellisville, MO). Endothelin-1 (ET-1) was from Peninsula Laboratories (Torrance, CA). Pertussis toxin (PTX), microcystin LR, CGP 20712A, ICI118551 and α-amanitin were from Sigma (Mississauga, Ontario). PD98059, SB203580, SP600125, LY294002, wortmannin and triciribine were from Calbio-chem. U0126 was from Upstate Cell Signaling Solutions. RNaseOut, dNTP Mix, First Strand buffer and M-MLVRT were from Invitrogen. Primers, as well as SyBR Green and ROX were also from Invitrogen. RNA extraction kits were from Qiagen. RT2 First strand kits, SABiosciences RT2 qPCR Master Mix and rat NFκB signalling pathway RT2 Profiler PCR arrays were from SABiosciences. Unless otherwise stated, all reagents were of analytical grade and were purchased from VWR Canlab (Ville Mont-Royal, Quebec) or Fisher Scientific (Mississauga, Ontario). [α32P]UTP (specific activity 3000 Ci/mmol) was from Perkin Elmer.

2.2. Isolation of nuclei

Rat cardiac nuclei were isolated as described previously [12]. Briefly, rat hearts were pulverized under liquid nitrogen, resuspended in cold PBS, and homogenized (Polytron, 8000 rpm; 2×10 s, Fraction 1). All subsequent steps were carried out on ice or at 5 °C. Homogenates were centrifuged for 15 min at 500 ×g. The resulting supernatants, referred to as Fraction 2, were diluted 1:1 with buffer A (10 mM K-HEPES (pH 7.9), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, 25μg/ml leupeptin, 0.2 mM Na3VO4), incubated 10 min on ice, and centrifuged for 15 min at 2000 ×g. The resulting supernatant was discarded. The pellet, referred to as crude nuclei (Fraction 3) was resuspended in buffer B (0.3 M K-HEPES pH 7.9, 1.5 M KCl, 0.03 M MgCl2, 25 μg/ml leupeptin, 0.2 mM Na3VO4), incubated on ice for 20 min, and centrifuged for 15 min at 2000 ×g. The pellet, an enriched nuclear fraction (Fraction 4), was resuspended in buffer C (20 mM Na-HEPES (pH 7.9), 25% (v/v) glycerol, 0.42 M NaCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.2 mM EGTA, 0.5 mM PMSF, 0.5 mM DTT, 25 μg/ml leupeptin, 0.2 mM Na3VO4) or 1 x transcription buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.9, 0.15 M KCl, 1 mM MnCl2, 6 mM MgCl2, 1 mM ATP, 2 mM DTT, 1 U/μl RNase inhibitor) and either used fresh or aliquoted, snap-frozen using liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C.

2.3. Transcription initiation

Measurements of transcription initiation were performed as previously described [8]. Briefly, 10 μl of isolated nuclei (resuspended in 1 x transcription buffer) were incubated at 30 °C for 30 min in the presence of the indicated agonist/antagonist and 10 μCi [α32P]UTP (3000 Ci/mmol). CTP and GTP were omitted to prevent chain elongation. Following termination of reactions by digestion with DNase I, nuclei were lysed with 10 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 10 mM EDTA and 1% SDS. Duplicate 5 μl aliquots were transferred onto Whatman GF/C glass fiber filters, washed twice with 5% TCA containing 20 mM sodium pyrophosphate, and air-dried. 32P incorporation was determined by liquid scintillation counting. DNA concentrations were determined spectrophotometrically and [32P]UTP incorporation expressed as cpm/μg DNA. Where indicated, isolated nuclei were pre-treated with the appropriate pharmacological inhibitors. Nuclei were either pre-treated at room temperature with 10 μM PD98059 for 1 h, 20 μM U0126 for 30 min, 100 nM wortmannin for 30 min, 50 μM LY294002 for 30 min, 10 μM SB203580 for 1 h, 20 μM SP600125 for 1 h, 1 μM triciribine for 30 min, 3 μM α-amanitin (a potent inhibitor of RNA polymerase II and III) for 30 min, or vehicle (DMSO) for either 30 min or 1 h, according to which inhibitor was used.

2.4. Immunoblotting

SDS PAGE and immunoblotting were performed as previously described [12]. Immunoreactive bands were quantified using a BioRad VersaDoc 4000 imaging system and Quantity One® software (Version 4.5.2 for Mac).

2.5. Quantitative real-time PCR

RNA was isolated from purified nuclei using Qiagen RNA extraction kits. To prepare cDNA, 1 μg of RNA was mixed with 100 ng of random primers and 1 μl of 10 mM dNTP mix, diluted to a final volume of 10 μl, heated to 65 °C for 5 min, and then immediately quick chilled on ice. Next, 4 μl of 5 x first strand buffer, 2 μl of 0.1 M DTT and 1 μl of RNase Out were added, and reactions were incubated for 2 min at 37 °C. Following the addition of 1 μl of M-MLV reverse transcriptase (200 units), reactions were mixed, centrifuged and then incubated for 10 min at 25 °C, 50 min at 37 °C, and finally 15 min at 70 °C. qPCR reactions, containing 12.5 μl of SyBR Green PCR master mix, 0.03 μl ROX Dye (an internal fluorescence standard), 2.5 μl of primers, and 10 μl of cDNA were 1 cycle of 10 min at 95 °C, then 40 cycles of (30 s at 95 °C, followed by 1 min at 60 °C and 1 min at 72 °C) using a Stratagene Mx3000P system. Samples were assayed in triplicate and normalized to β-actin expression. Primers used for real-time qPCR are shown in Table 1. The specificity of each primer pair for the amplicon of interest was verified by dissociation curve analysis.

Table 1.

Primers used during real-time qPCR

| Target | Primers |

|---|---|

| 18S S | 5′-ACG GAC CAG AGC GAA AGC AT-3′ |

| 18S AS | 5′-TGT CAA TCC TGT CCG TGT CC-3′ |

| NFkB S | 5′-CTG CGA TAC CTT AAT GAC AGC G-3′ |

| NFkB AS | 5′-AAT TTT GGC TTC CTT TCT TGG CT-3′ |

| β-Actin S | 5′-TTC AAT TCC ATC ATG AAG TGT G-3′ |

| β-Actin AS | 5′-CTG ATC CAC ATC TGC TGG AAG GTG-3′ |

S, sense; AS, anti-sense.

2.6. RT2 Profiler PCR arrays

RNA was isolated from purified nuclei using Qiagen RNA Extraction Kits. cDNA was prepared from 1 μg of RNA using the SABiosciences RT2 First Strand Kit. cDNA (102 μl) was mixed with 1275 μl of 2 x SABiosciences RT2 qPCR Master Mix plus 1173 μl of ddH2O and 25 μl of the final mixture was transferred to each well of the RT2 PCR array. Arrays were assayed for 1 cycle of 10 min at 95 °C, then 40 cycles of (15 s at 95 °C, followed by 1 min at 60 °C) using a Stratagene Mx3000P system. All conditions were done in triplicate and normalized to the vehicle control. Each 96-well plate also included primers for 5 housekeeping genes as well as positive and negative controls. Results were analyzed using web-based analysis software (SABiosciences). Changes were considered significant when p<0.05.

2.7. Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± the standard error of the mean (S.E.M.). The significance of differences between groups was determined using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison tests (Prism 4.0cx, GraphPad Software). Differences were considered significant when p<0.05.

2.8. Miscellaneous methods

Protein concentrations were determined by the method of Bradford using bovine γ-globulin as a standard.

3. Results

3.1. Regulation of β-adrenergic transcriptional responses in isolated nuclei by protein kinases

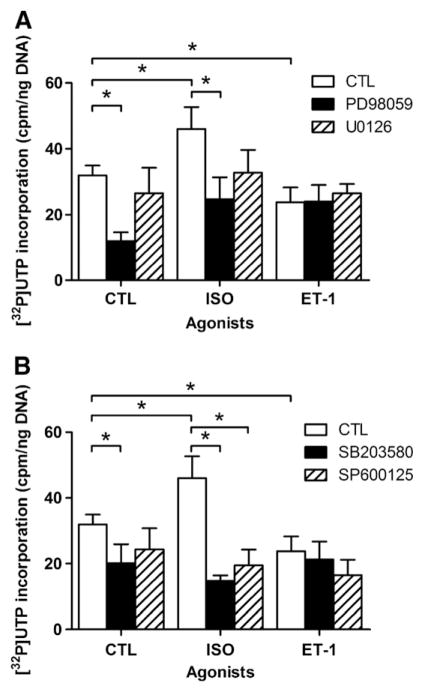

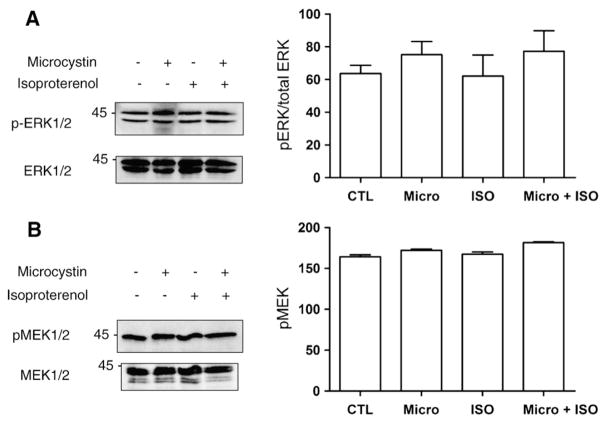

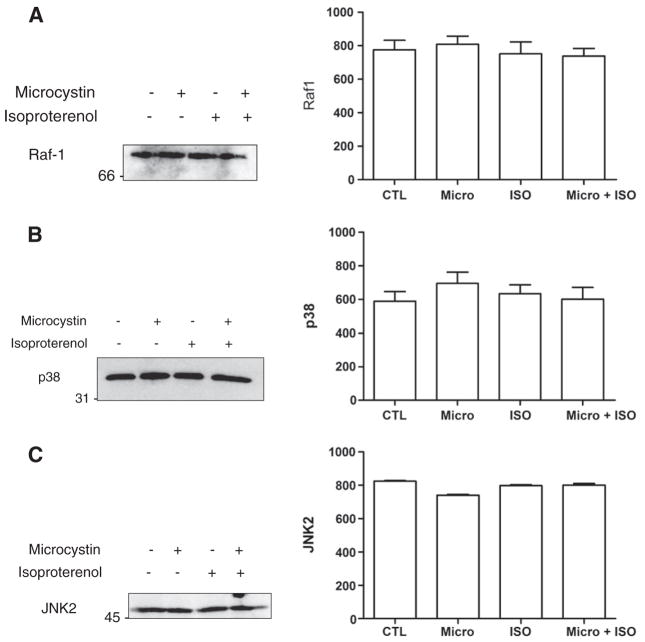

We have shown previously that isoproterenol (ISO) increases de novo RNA synthesis in nuclei freshly isolated from rat heart [8]. MAPK and PKB signalling are known to lead to the phosphorylation of a variety of transcription factors, including some that are regulated by multiple signalling pathways. ERK1/2 primarily activates activator protein-1 (AP-1) through its coordinated stimulation of c-fos, while JNK also activates AP-1, though through its control of c-jun expression [13]. PKB on the other hand primarily activates the FoxO family of transcription factors as well as NFκB [14]. Moreover, ATF-2 and p53 can be activated by JNK as well as p38 MAPK, while c-myc has been shown to be activated by ERK1/2, ERK5 and JNK [15–17]. Hence, it is reasonable to propose that one or more of these pathways may be involved in regulating transcription in response to activation of βARs in the nuclear membrane. First, we set out to determine if the ERK1/2 MAPK pathway modulated the effects of βAR stimulation on transcriptional initiation. Freshly isolated nuclei were incubated with ISO (1 μM), in the absence or presence of an inhibitor of either MEK1/2 activation (PD98059) or activity (U0126), and [α32P]UTP to measure initiation of RNA transcription. Endothelin type B receptors (ETB) have also been shown to be present on the nuclear envelope [12]; hence, purified nuclei were also treated with endothelin 1 (ET-1, 10 nM). Interestingly, whereas ISO increased [32P]UTP incorporation (Fig. 1A) treatment with ET-1 decreased RNA transcription below control levels. Treatment with PD98059 also resulted in a decrease in basal levels of de novo transcription whereas U0126 did not suggesting a difference between having activatable MEK1/2 or not. However, pre-treatment with either PD98059 or U0126 blocked the increase in RNA synthesis following ISO treatment. Neither compound altered the inhibition of RNA synthesis induced by ET-1, suggesting that the signals from βAR and ETB are compartmentalized differently. The presence of the activated, phosphorylated form of ERK1/2 in isolated nuclei was confirmed by immunoblot, where isolated nuclei were pretreated with either vehicle, ISO, microcystin LR, or ISO and microcystin LR and then probed with anti-phosphoERK1/2 (p42/p44, Fig. 2A). The presence of other components of the ERK1/2 pathway was also assessed by immunoblotting, with the results demonstrating the presence of both Raf-1 and the phosphorylated form of MEK1/2 (Figs. 2B and 3A). The ability of PD98059 to reduce the basal level of transcription, taken together with the ability of both PD98059 and U0126 to block the ISO-induced up regulation of RNA synthesis, and the presence of Raf-1, MEK1/2 and ERK1/2 immunoreactivity, demonstrate that all of the components of the ERK1/2 MAPK pathway are present in the nucleus and appear to be already in an activated form prior to βAR stimulation. Isoproterenol treatment did not activate nuclear ERK1/2 per se. A number of signals likely converge on ERK1/2 and other MAPKs suggesting that the net state of their activation may serve a modulatory role for βAR-mediated transcription.

Fig. 1.

Effect of MAP kinase inhibition on transcription initiation. A) Enriched nuclear fractions were stimulated with either 1 μM isoproterenol (ISO), or 100 nM ET-1. [α32P] UTP incorporation was measured in either untreated nuclei or nuclei pretreated with either an inhibitor of MEK1/2 activation, PD98059 (10 μM, 1 h), or activity U0126 (20 μM, 30 min). B) Enriched nuclear fractions were stimulated with either 1 μM isoproterenol (ISO), or 100 nM ET-1. [α32P]UTP incorporation was measured in either untreated nuclei or nuclei pretreated with p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 (50 μM, 30 min) or JNK MAPK inhibitor SP600125 (100 nM, 30 min). Data represent mean±S.E. of at least three separate experiments performed in triplicate. Significant differences (* for p<0.05) were determined by one-way ANOVA for three or more experiments.

Fig. 2.

Phosphorylation of ERK1/2 and MEK1/2 in isolated nuclei following treatment with isoproterenol. A) Enriched nuclear fractions were either untreated (1), treated with 1 μM microcystin LR (an inhibitor of type I and IIA protein serine/threonine phosphatases) (2), stimulated with 1 μM isoproterenol (3), or with 1 μM isoproterenol plus 1 μM microcystin LR (4). All treatments were for 30 min at 30 °C. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose and probed with an anti-phospho ERK1/2 (threonine 202/tyrosine 204) antibody. B) Enriched nuclear fractions were treated as described in A, separated on SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose, and probed with an anti-phospho MEK1/2 antibody. Data represent mean±S.E. of at least three separate experiments. Significant differences (* for p<0.05) were determined using one way ANOVA for three or more experiments.

Fig. 3.

Detection of Raf1, p38 and JNK2 in isolated nuclei. Enriched nuclear fractions were treated as described in Fig. 2A, separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose and probed with A) an anti-phospho Raf1 antibody, B) an anti-p38 antibody or C) an anti-JNK2 antibody. Images on the left of each panel show representative immunoblots and data on the right of each panel represent mean±S.E. of at least three separate experiments. Significant differences (* for p<0.05) were determined by one-way ANOVA for three or more experiments.

Next, we examined the potential involvement of the p38 and JNK MAPK pathways. Pre-treatment with SB203580, an inhibitor of p38α and p38β activity, again resulted in the inhibition of basal RNA synthesis (Fig. 1B), while pre-treatment with SP600125 (which inhibits JNK) showed an inhibitory trend that did not reach statistical significance. Both SB203580 and SP600125 blocked the ISO-induced increase in transcription, but had no appreciable effect on the inhibition of transcription induced by ET-1, again highlighting differences in how the two signalling pathways are organized in nuclei. Both p38 and JNK were detected by immunoblot (Fig. 3B, C), however levels of phospho-p38 and phospho-JNK were too low to detect with the antibodies available (data not shown). These results indicate that both the p38 and JNK MAPK signalling cascades are present within the nucleus. The ability of p38 and JNK inhibitors to completely block ISO-induced up regulation of RNA synthesis, while not being directly activated by isoproterenol treatment, seems to indicate that these MAPKs might also play important modulatory roles in this process. Thus the different MAPK systems all seem to mediate the ability of βAR to increase transcriptional activity. Systems which control MAPK activity or distribution in the nucleus would either be permissive or restrictive to transcriptional regulation by βAR.

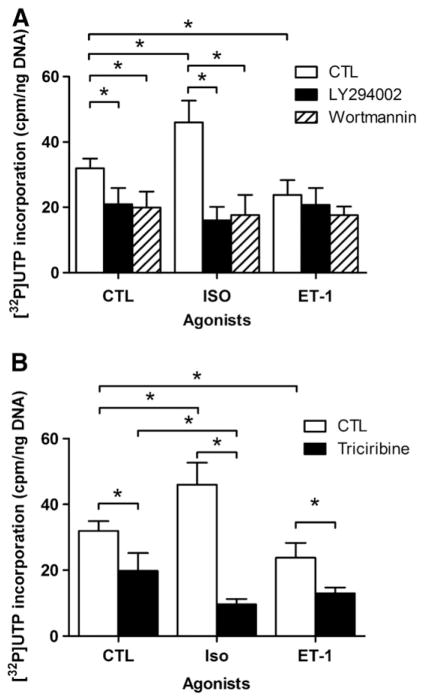

We then turned our attention to the PI3K/PKB pathway. LY294002 and wortmannin (which inhibit PI3K) both inhibited de novo transcription in the absence of agonist stimulation (Fig. 4A), and blocked the increase in transcription in response to ISO. Again neither inhibitor had any effect on ET-1 induced inhibition. In line with these experiments, it was not surprising that pre-treatment with the PKB inhibitor triciribine alone resulted in a similar decrease in basal de novo transcription since PKB is downstream of PI3K (Fig. 4B). A striking finding was that triciribine not only blocked the increase in transcription produced by ISO, but actually converted the normal stimulatory effect of ISO to an inhibitory one, i.e. levels of RNA synthesis initiation were lower in the presence of triciribine and ISO than with triciribine alone. Thus, the ability of triciribine to turn ISO from stimulatory to inhibitory indicates that ISO, when PKB cannot be activated, becomes an inverse agonist for the transcriptional pathway. In addition, triciribine enhanced the inhibitory effect of ET-1, suggesting that ET-1 and triciribine inhibit de novo RNA synthesis by two distinct pathways.

Fig. 4.

Effect of PI3K/PKB inhibition on transcription initiation. A) Enriched nuclear fractions were stimulated with either 1 μM isoproterenol (ISO), or 100 nM ET-1. [α32P]UTP incorporation was measured in nuclei either untreated or pretreated with PI3K inhibitors LY294002 (50 μM, 30 min) or wortmannin (100 nM, 30 min). B) Enriched nuclear fractions were stimulated with either 1 μM isoproterenol (ISO), or 100 nM ET-1. [α32P]UTP incorporation was measured in nuclei either untreated or pretreated with PKB inhibitor triciribine (1 μM, 30 min). Data represent mean±S.E. of at least three separate experiments performed in triplicate. Significant differences (* for p<0.05) were determined using one-way ANOVA for three or more experiments.

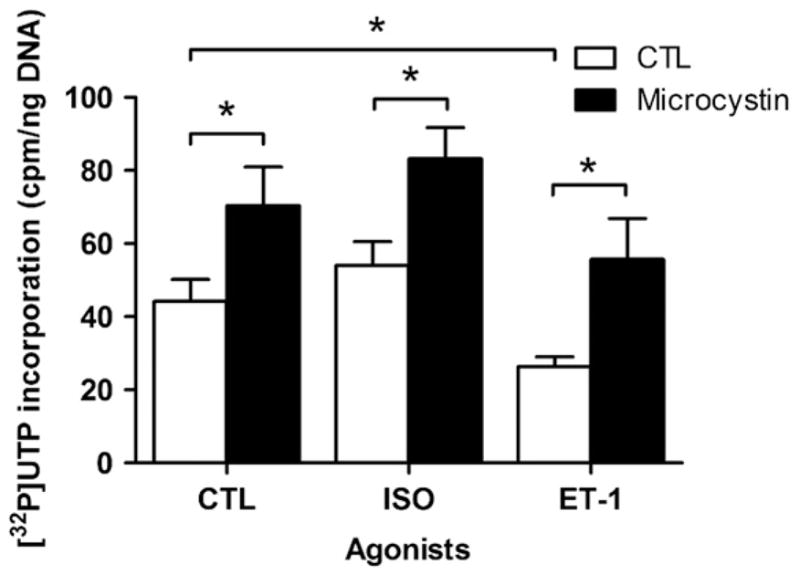

3.2. Regulation of β-adrenergic transcriptional responses in isolated nuclei by protein serine/threonine phosphatase activity

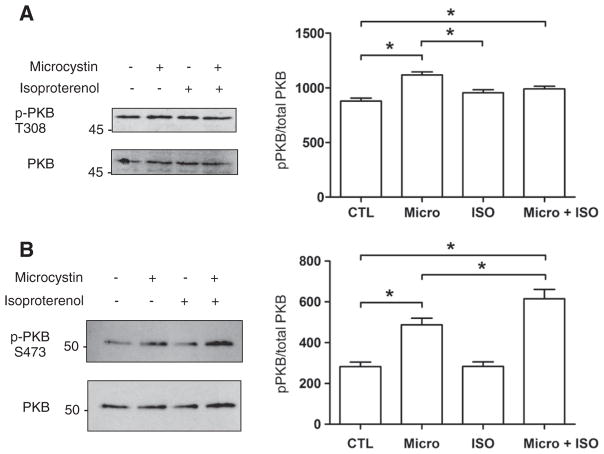

Given that ERK1/2, p38, JNK and PKB are all protein serine/threonine kinases, we next examined the involvement of protein serine/threonine phosphatase activity in regulating [32P]UTP incorporation. Microcystin LR, a potent inhibitor of type I and IIA protein serine/threonine phosphatases, produced 50% increases in transcription initiation with vehicle, ISO, and ET-1 (Fig. 5). The latter observation is interesting in the sense that it changes the direction of ET-1 signalling with respect to transcription initiation in an analogous way to how triciribine affected the response to ISO. Since PKB inhibition converted ISO from an activator into an inhibitor of transcriptional initiation, the effect of ISO and microcystin upon PKB phosphorylation was also examined. Isolated nuclei were pretreated with either vehicle, ISO, microcystin LR, or ISO and microcystin, and either phospho-PKB threonine 308 or serine 473 was quantified by immunoblotting. Treatment with microcystin increased phosphorylation of PKB at both threonine 308 and serine 473 (Fig. 6A, B) indicating the presence of, and dephosphorylation by, type I and/or IIA protein serine/threonine phosphatase activity in isolated nuclei. Additionally, although ISO alone did not increase PKB phosphorylation at either threonine 308 or serine 473, treatment with ISO in the presence of microcystin increased the level of PKB phosphorylation at both sites, particularly in the case of serine 473, indicating that ISO is in fact able to activate PKB in the nucleus, but that PKB is subject to rapid dephosphorylation. The levels of both total ERK and total PKB immunoreactivity remained constant (Figs. 2A and 6A, B), confirming that the changes in phospho-PKB levels were due to activation of local PKB pools in isolated nuclei following receptor stimulation.

Fig. 5.

Effect of microcystin on transcription initiation. Enriched nuclear fractions were stimulated with either 1 μM isoproterenol (ISO), or 100 nM ET-1. [α32P]UTP incorporation was measured in nuclei either untreated or pretreated with 1 μM microcystin LR (an inhibitor of type I and IIA protein serine/threonine phosphatases) prior to the addition of agonist. Data represent mean±S.E. of at least three separate experiments performed in triplicate. Significant differences (* for p<0.05) were determined using one-way ANOVA for three or more experiments.

Fig. 6.

Phosphorylation of PKB following treatment with isoproterenol. Enriched nuclear fractions were treated as described in Fig. 2A, separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose and probed with A) an anti-phospho PKB (threonine 308) antibody or B) an anti-phospho PKB (serine 473) antibody. Images on the left of each panel show representative immunoblots and data on the right of each panel represent mean±S.E. of at least three separate experiments. Significant differences (* for p<0.05) were determined by one-way ANOVA for three or more experiments.

3.3. Targets of β-adrenergic transcriptional responses in isolated nuclei

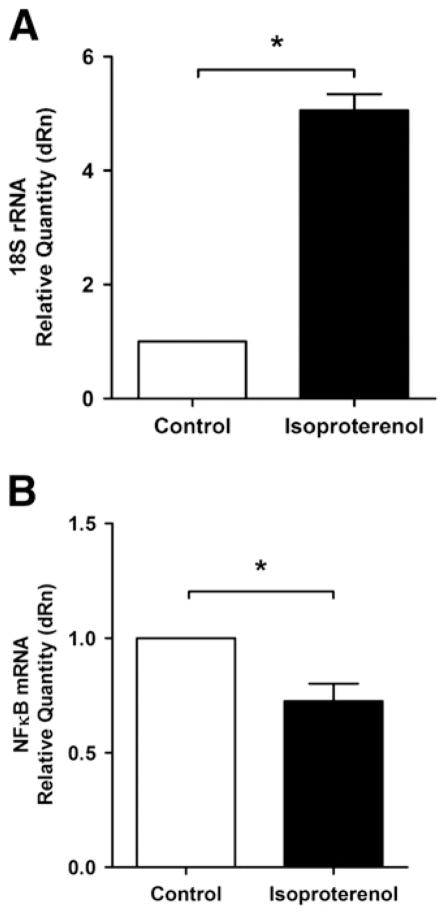

We next wished to determine which type(s) of RNA were being altered upon stimulation of βAR on isolated nuclear membranes. Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) represents the majority of the RNA within the cell. Consequently, to identify if an increase in rRNA synthesis was responsible for the observed increase in de novo RNA synthesis, isolated nuclei were treated with ISO or vehicle for 30 min, 1, 6, 12 or 24 h and the quantity of 18 S rRNA determined by qPCR, and normalized against β-actin mRNA. Large variations in the abundance of 18 S rRNA could be seen at the later time points, including a decrease at 12 h and a significant increase at 24 h (data not shown). However, a closer examination of the qPCR data revealed the variability observed from the 6 h time point forward was due to changes in both 18 S rRNA and β-actin mRNA levels, which appeared to be degraded more rapidly in the ISO treated samples. For that reason we decided to focus solely on the 30 min time point. A significant increase, of close to 5 fold, in 18 S rRNA was observed, indicating that an increase in rRNA is likely primarily responsible for the increase in global transcription observed upon βAR stimulation (Fig. 7A).

Fig. 7.

βAR stimulation alters the abundance of 18 S rRNA and NFκB mRNA. A) Enriched nuclear fractions were stimulated with either 1 μM isoproterenol or vehicle for 30 min at 37 °C. RNA was then extracted, cDNA prepared and 18 S rRNA (A) or NFκB1 mRNA (B) quantified by qPCR. CT values were normalized to those for β-actin mRNA. Data represent mean±S.E. of at least three separate experiments. Significant differences (* for p<0.05) were determined by one way ANOVA for three or more experiments.

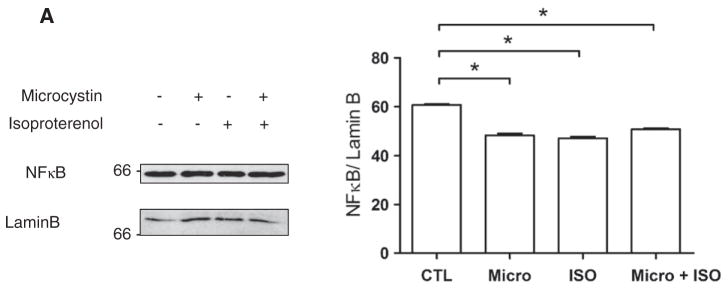

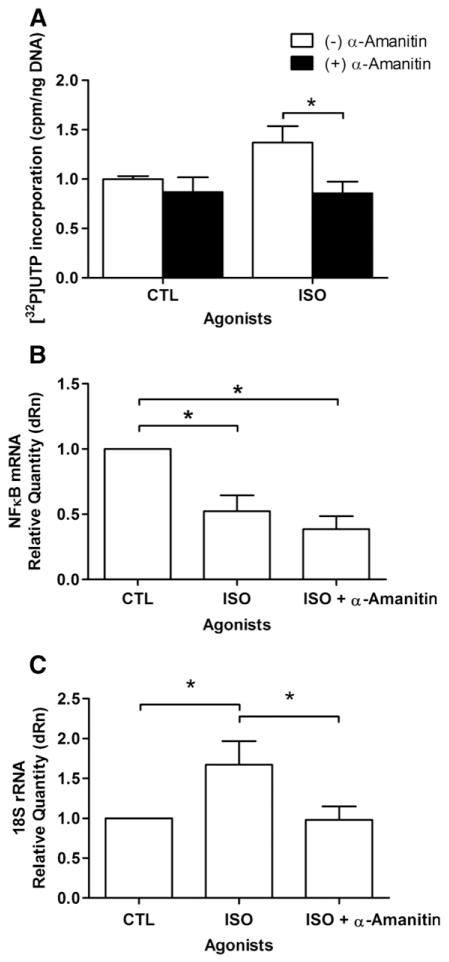

We also wanted to determine whether mRNA abundance was affected in response to activation of βAR in the nuclear membrane. Given that NFκB is a well characterized transcription factor downstream of PKB signalling, and its message levels have recently been shown to be regulated by another nuclear GPCR, the type 1 angiotensin II receptor (AT-1) [18], we reasoned that it might be an interesting candidate. Using primers directed against NFκB1, we observed a decrease in NFκB mRNA levels after 30 min of stimulation with ISO (Fig. 7B). These results were further confirmed at the protein level as a small decrease in NFκB was observed following treatment with ISO (Fig. 8). Levels of NFκB protein were normalized using an anti-lamin B antibody. Hence, the abundance of NFκB mRNA appears to be down-regulated by nuclear βAR stimulation. The fact that inhibition of RNA polymerase II (RNAP II), with α-amanitin, substantially reduced the effects of ISO on transcription initiation (Fig. 9A) also suggests that some of the transcriptional events depend on this enzyme. ISO reduced NFκB mRNA levels and no added effect was observed in the presence of α-amanitin (Fig. 9B). Interestingly, we also noted an effect of α-amanitin on 18 S rRNA levels, which depends on RNAP I (Fig. 9C).

Fig. 8.

Detection of NFκB following treatment with isoproterenol. Enriched nuclear fractions were treated as described in Fig. 2A, separated by SDS-PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose and probed with an anti-NFκB antibody. Expression of NFκB was normalized to the levels of Lamin B protein. Images on the left of each panel show representative immunoblots and data on the right of each panel represent mean±S.E. of at least three separate experiments. Significant differences (* for p<0.05) were determined by one-way ANOVA for three or more experiments.

Fig. 9.

Effects of α-amanitin on isoproterenol-mediated transcription initiation. A) Nuclear [α32P]UTP incorporation was determined following α-amanitin (3 μM, 30 min) or vehicle pre-treatment and subsequent treatment with 1 μM isoproterenol. B) Levels of NFκB1 mRNA following α-amanitin or vehicle pre-treatment and subsequent treatment with 1 μM isoproterenol. Samples were treated as described above in Fig. 3. CT values were normalized to β-actin mRNA levels. C) Levels of 18 S rRNA following α-amanitin or vehicle pre-treatment and subsequent treatment with 1 μM isoproterenol. Samples were treated as described above in Fig. 3. CT values were normalized to β-actin mRNA levels. Data represent mean±S.E. of at least three separate experiments. Significant differences (* for p<0.05) were determined by one way ANOVA for three or more experiments.

To further explore the regulation exerted by nuclear βARs on the NFκB pathway, we used RT2 Profiler PCR arrays (purchased from SABiosciences) with RNA from isolated nuclei treated with ISO or vehicle for 30 min in the presence or absence of either ERK1/2 inhibition (U0126) or PKB inhibition (triciribine, Table 2). The abundance of several transcripts was significantly altered in each of the conditions. Consistent with our initial experiments with NFκB, treatment with ISO also resulted in the down-regulation of ATF-2, Il1r1 and Tnfrsf1b, along with the modest up-regulation of Ripk2. ATF-2, which is known to interact with c-jun, is a transcription factor primarily regulated by the stress activated MAPKs JNK and p38 and is known to play a role in the hypertrophic response [19], while Il1r1 is mainly involved in the immune and inflammatory response, through its interaction with Myd88, although it also plays a role in the activation of NFκB [20]. Tnfrsf1b plays a role in the activation of NFκB, but only in the absence of Rip proteins like Ripk2 [21]. Taken together these results support the idea that ISO stimulation leads to general inhibition of the NFκB pathway along with the suppression of the inflammatory response.

Table 2.

RT2 Profiler PCR array analysis of the NFkB signalling pathway in isolated cardiac nuclei

| Gene

|

Treatment

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symbol | Name | ISO | ISO+U0126 | ISO+triciribine |

| ATF-2 | Activating transcription factor 2 | −1.89 (0.042) | 1.32 (0.202) | 1.18 (0.448) |

| Casp1 | Caspase 1 | −1.04 (0.906) | 1.43 (0.093) | 1.49 (0.045) |

| Lpar1 | Lysophosphatidic acid receptor 1 | 1.15 (0.376) | 1.51 (0.193) | 1.28 (0.016) |

| Il1r1 | Interleukin 1 receptor, type 1 | −1.20 (0.017) | 1.16 (0.405) | −1.16 (0.776) |

| Irak2 | Interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase 1 | −1.21 (0.615) | 2.12 (0.012) | 1.25 (0.310) |

| Jun | Jun oncogene | −1.45 (0.176) | 1.70 (0.086) | 1.04 (0.975) |

| Tnfsf14 | Tumor necrosis factor superfamily, member 14 | −1.12 (0.648) | 1.16 (0.416) | 1.43 (0.069) |

| Myd88 | Myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88 | −1.22 (0.489) | 1.42 (0.007) | 1.22 (0.194) |

| Ippk | Inositol 1,3,4,5,6 pentakisphosphate 2-kinase | 1.27 (0.585) | 2.17 (0.003) | 1.20 (0.305) |

| Ripk2 | Receptor-interacting serine-threonine kinase 2 | 1.33 (0.023) | 1.11 (0.562) | −1.10 (0.459) |

| Tlr6 | Toll-like receptor 6 | 1.51 (0.228) | 1.16 (0.418) | 1.43 (0.068) |

| Tnfrsf1b | Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily 1b | −2.15 (0.049) | 1.28 (0.147) | 1.36 (0.066) |

| Tradd | Tnfrsf1a-associated via death domain | 1.74 (0.071) | 1.11 (0.544) | 1.12 (0.523) |

| Traf3 | TNF receptor-associated factor 3 | 1.10 (0.832) | −1.33 (0.008) | −1.32 (0.219) |

Data shown are expressed as the fold-change in mRNA abundance relative to a vehicle control. p-values are indicated in parentheses. (n=3).

Further, isolated nuclei pretreated with U0126 prior to ISO stimulation showed an increase in Irak2, Myd88 and Ippk along with a decrease in Traf3. Both the protein kinase Irak2 and adaptor protein Myd88 play key roles in the activation of NFκB [22], whereas Traf3 has been shown to inhibit NFκB activation [23]. The role of the enzyme Ippk is still unclear, but it has been shown to play a role in the inhibition of apoptosis [24]. In addition, c-jun is also up-regulated in comparison to the ISO stimulated nuclei. Our results indicate that inhibition of ERK1/2 activation by U0126 in the presence of ISO leads to the activation of NFκB and the suppression of apoptosis. Hence, U0126 completely reverses the inhibitory effect exerted on the NFκB pathway by ISO stimulation, indicating that ERK1/2 might be responsible for this inhibitory effect.

Isolated nuclei pretreated with triciribine prior to ISO stimulation showed an increase in Casp1 and Lpar1 mRNA, along with increases in Tnfsf14, Tlr6 and Tnfrsf1b that were not quite statistically significant. Casp1 is an enzyme involved in the up-regulation of inflammation and apoptosis [25], while Lpar1 is a GPCR involved in developmental, physiologic and pathophysiologic processes, and has also been shown to activate PKB as well as Rho pathways [26]. In addition, Tnfsf14 and Tnfrsf1b both have been shown to play a role in the activation of NFκB and apoptosis [21], while Tlr6, through its interaction with Tlr2, is involved in the immune response [27]. Hence, it appears that PKB inhibition leads to an increase in the abundance of mRNAs arising from genes important for induction of apoptosis, suggesting a role for PKB in the inhibition of apoptosis following nuclear βAR stimulation. The results of the RT2 PCR arrays were in accordance with the qPCR data, where ISO stimulation leads to the reduction of NFκB mRNA, while also demonstrating a role for both ERK1/2 and PKB in modulating this pathway. Taken together, our data indicate that nuclear βAR modulate a number of transcriptional events through localized signalling pathways (i.e. PKB activation) and these are modulated by the tone of ERK, p38 and protein phosphatase signalling in the nucleus.

4. Discussion

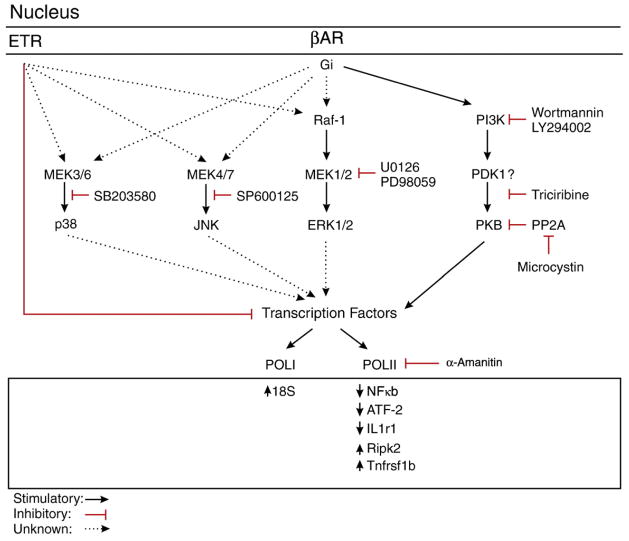

We have demonstrated that GPCRs located on the nuclear membrane are not only functional with respect to ligand binding and effector activation, but also can play very distinct roles in regards to the regulation of RNA synthesis (summarized in Fig. 10). Whereas βAR activation has been shown previously to both activate AC via Gs and stimulate global RNA synthesis via Gi [8], we now show that ETR activation by ET-1 has the opposite effect, actually inhibiting de novo RNA synthesis, in a protein phosphatase-sensitive manner. These two types of GPCRs exert opposing effects on RNA synthesis indicates that they either integrate signals relevant for target binding sites in the genome or may have distinct sets of targets. Additionally, βARs in the nuclear membrane, similarly to the βARs located at the level of the plasma membrane, appear to be able to activate the PI3K/PKB pathway, a process which also appears to be highly regulated via serine/threonine phosphatases. MAPK signalling pathways, although not directly activated by the βAR in the nucleus, do in fact modulate the ability of βAR to mediate transcriptional events, again in a manner that is sensitive to serine/threonine phosphatase inhibition. Different levels of control are also suggested by the differences in basal transcriptional activity in the presence of an activatable MEK or not. Whereas PD98059 inhibits MEK1/2 activation, U0126 inhibits MEK1/2 activity. As a result, in the nuclei treated with U0126, MEK1/2 can still be activated and hence might play some other role unrelated to its kinase activity per se, perhaps as a scaffold.

Fig. 10.

Signalling diagram of post-nuclear βAR and ETR activation. Signalling diagram illustrating major findings of our study.

Nuclear-targeted PKB overexpression has previously been shown to have several beneficial effects including enhanced contractility and protection from ischaemic injury [28], while sustained PKB activation can lead to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy primarily via phosphorylation of substrates localized to the cytoplasm [11,29], indicating that PKB not only plays important roles in the nuclei of cardiomyocytes, but that these roles can differ depending on its localization. Furthermore, we show that inhibition of PKB with triciribine causes ISO to behave as an inverse agonist, leading to the inhibition of RNA synthesis, as opposed to its previously noted stimulatory effect. At the level of the plasma membrane, PI3K activation leads to the recruitment of phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-1 (PDK1) and PKB via their pleckstrin homology (PH) domains, where PDK1 is able to phosphorylate PKB at threonine 308 and thereby activate it [30]. Once activated, PKB can accumulate both in the cytoplasm and the nucleus [11,31,32]. However, inhibition of PI3K with either wortmannin or LY294002 did not produce the same effect, indicating that either PKB activation in this case might be mediated by another pathway, or that PKB is only one of multiple effectors activated downstream of PI3K in the nucleus. One such possibility would be that PKB is being activated by DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PK) through the control of cAMP levels [33,34], although in this case DNA-PK would not be exported, but would instead phosphorylate PKB within the nucleus. Moreover, it is unclear how inhibition of PKB with triciribine reverses the effect of ISO treatment on transcriptional activity. One possibility is that the conformational state of the receptor is altered such that ISO now acts as an inverse agonist for the transcriptional pathway. Recent evidence demonstrates that βAR inverse agonists for AC may act as agonists for activation of MAPKs via a β-arrestin-mediated pathway [35]. In our case, similar pleiotropic effects of ISO may result from PKB-mediated alterations in the receptor or its signalling partners, leading to the inhibition of de novo RNA synthesis, when PKB is inhibited and activation when it remains activatible. Given the high level of basal RNA transcription seen, in the case where PKB is inhibited, ISO might simply be inhibiting the spontaneous activity of these nuclear localized receptors in a functionally selective manner. Further experiments to examine the involvement of β-arrestin in this pathway and the identification of the relevant PKB targets are required. At this point, it is still unclear if the nuclear localized receptors interact with β-arrestin or GRKs although both are present in the nucleus [36,37]. Pim-1, a protein kinase downstream of PKB, may also be involved as it plays a pivotal role in the inhibition of both apoptosis and hypertrophy in cardiomyocytes, and its expression affects both JNK and ERK pathways [38]. This may in part explain why each of the MAPK pathways appears to play some role in the βAR stimulated increase in de novo RNA synthesis. Additionally, Pim-1 has been shown to phosphorylate and stabilize c-myc [39]. Given the established role of c-myc as an activator of RNAP I [40], this may suggest a pathway involving the receptor, PKB and RNAP I being important for rRNA transcription.

Although the bulk of the transcriptional response to βARs stimulation involved synthesis of rRNA, we did detect regulation of specific mRNA targets, such as NFκB, which was down-regulated in response to treatment with ISO, and our experiments with α-amanitin demonstrate a role for RNAP II in the receptor-mediated transcriptional responses. The effects on rRNA transcription in response to pretreatment with α-amanitin were somewhat surprising. A similar effect of α-amanitin on RNAP I- and RNAP III-transcribed genes has been reported previously [41,42] and RNAP II was recently shown to bind near and regulate the transcription of genes transcribed by RNAP III [41]. Alternatively, it may be that signalling via the βAR alters the activity and/or distribution of shared components of RNAP I and RNAP II but this is beyond the scope of the present study.

Genes for other modulators and targets of the NFκB pathway, such as ATF-2 and Tnfrsf1b were also down-regulated. Nuclear GPCRs may therefore be important regulators of both apoptosis and the inflammatory pathway in the heart. Moreover, the fact that both ERK1/2 and PKB inhibition seem to reverse the effects of ISO stimulation on these identified genes would seem to indicate that both pathways play a role in the regulation of gene expression by nuclear βARs. This may be through MAPK or PKB modulation of the signalling proteins themselves, modulation of the transcriptional machinery or via alterations in the occupancy of chromatin sites by ERK and other protein kinases [43,44]. Further, given the already identified role of MAPKs in regulating mRNA stability [45], further experiments need to be conducted to determine if the regulation that we see is actually due to a changes in the level of de novo mRNA synthesis or reduced mRNA stability. These results reveal that βARs located on the nuclear envelope can in fact affect specific genes, and pathways, though further large-scale analysis by microarray would be useful in developing a broader picture of genes regulated by these receptors.

5. Conclusions

We have shown that ETB and βARs in the nuclear membrane can effect RNA synthesis, and in opposing ways, implying that they have different roles to play in regulating this process. Additionally, using a pharmacological approach we have shown that MAPK and PKB modulate RNA synthesis observed following ISO treatment in isolated nuclei. Moreover, we show that not only is rRNA synthesis increased but specific mRNA targets, such as NFκB, also appear to be regulated. Together, these results begin to demonstrate that not only are these GPCRs present at the level of the nuclear membrane, functional with respect to ligand binding and effector activation, but also have a role to play in the regulation of gene transcription, in addition to other functions yet to be discovered.

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP-77791 to BGA and MOP-79354 to TEH) and the Fonds de l’Institut de Cardiologie de Montréal (FICM). BGA was a New Investigator of the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada and a Senior Scholar of the Fondation de la Recherche en Santé du Québec (FRSQ). TEH holds a Chercheur National award from the FRSQ. We thank Jason Tanny at McGill University for helpful discussions.

Abbreviations

- AC

adenylyl cyclase

- ATP

adenosine triphosphate

- βAR

β-adrenergic receptor

- CAMKII

Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II

- DNA

deoxyribonucleic acid

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- ET-1

endothelin 1

- ERK

extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- GPCR

G protein-coupled receptor

- HRP

horseradish peroxide

- ISO

isoproterenol

- JNK

c-Jun N-terminal kinase

- MAPK

mitogen activated protein kinase

- NFκB

nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B-cells

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- PI3K

phosphoinositide 3-kinase

- PKA

protein kinase A

- PKB

protein kinase B

- PMSF

phenylmethanesulphonylfluoride

- PTX

pertussis toxin

- qPCR

quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

- RNA

ribonucleic acid

- RNAP

RNA polymerase

- TCA

trichloroacetic acid

- TX-100

Triton X-100

- UTP

uridine 5′triphosphate

References

- 1.Tevaearai HT, Koch WJ. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2004;14(6):252. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xiao RP, Zhu W, Zheng M, Cao C, Zhang Y, Lakatta EG, Han Q. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2006;27(6):330. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2006.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuschel M, Zhou YY, Cheng H, Zhang SJ, Chen Y, Lakatta EG, Xiao RP. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(31):22048. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.31.22048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu WZ, Wang SQ, Chakir K, Yang D, Zhang T, Brown JH, Devic E, Kobilka BK, Cheng H, Xiao RP. J Clin Invest. 2003;111(5):617. doi: 10.1172/JCI16326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng HJ, Zhang ZS, Onishi K, Ukai T, Sane DC, Cheng CP. Circ Res. 2001;89(7):599. doi: 10.1161/hh1901.098042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boivin B, Vaniotis G, Allen BG, Hebert TE. J Recept Signal Transduct Res. 2008;28(1–2):15. doi: 10.1080/10799890801941889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jong YJ, Kumar V, O’Malley KL. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(51):35827. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.046276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boivin B, Lavoie C, Vaniotis G, Baragli A, Villeneuve LR, Ethier N, Trieu P, Allen BG, Hebert TE. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;71(1):69. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sastri M, Barraclough DM, Carmichael PT, Taylor SS. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(2):349. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408608102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Willard FS, Crouch MF. Immunol Cell Biol. 2000;78(4):387. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.2000.00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miyamoto S, Rubio M, Sussman MA. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;82(2):272. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boivin B, Chevalier D, Villeneuve LR, Rousseau E, Allen BG. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(31):29153. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301738200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turjanski AG, Vaque JP, Gutkind JS. Oncogene. 2007;26(22):3240. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salminen A, Kaarniranta K. Cell Signal. 2010;22(4):573. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buschmann T, Potapova O, Bar-Shira A, Ivanov VN, Fuchs SY, Henderson S, Fried VA, Minamoto T, Alarcon-Vargas D, Pincus MR, Gaarde WA, Holbrook NJ, Shiloh Y, Ronai Z. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21(8):2743. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.8.2743-2754.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.English JM, Pearson G, Baer R, Cobb MH. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(7):3854. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.7.3854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gupta S, Campbell D, Derijard B, Davis RJ. Science. 1995;267(5196):389. doi: 10.1126/science.7824938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tadevosyan A, Maguy A, Villeneuve LR, Babin J, Bonnefoy A, Allen BG, Nattel S. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(29):22338. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.121749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lim JY, Park SJ, Hwang HY, Park EJ, Nam JH, Kim J, Park SI. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2005;39(4):627. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2005.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Croker BA, Lawson BR, Rutschmann S, Berger M, Eidenschenk C, Blasius AL, Moresco EM, Sovath S, Cengia L, Shultz LD, Theofilopoulos AN, Pettersson S, Beutler BA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(39):15028. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806619105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pimentel-Muinos FX, Seed B. Immunity. 1999;11(6):783. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80152-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ringwood L, Li L. Cytokine. 2008;42(1):1. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2007.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bista P, Zeng W, Ryan S, Bailly V, Browning J, Lukashev ME. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(17):12971. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.076091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Verbsky J, Majerus PW. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(32):29263. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503366200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li J, Yuan J. Oncogene. 2008;27(48):6194. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Choi JW, Herr DR, Noguchi K, Yung YC, Lee CW, Mutoh T, Lin ME, Teo ST, Park KE, Mosley AN. J Chun, Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2010;50:157. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.010909.105753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Farhat K, Riekenberg S, Heine H, Debarry J, Lang R, Mages J, Buwitt-Beckmann U, Roschmann K, Jung G, Wiesmuller KH, Ulmer AJ. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;83(3):692. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0807586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perrino C, Rockman HA, Chiariello M. Vascul Pharmacol. 2006;45(2):77. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2006.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matsui T, Li L, Wu JC, Cook SA, Nagoshi T, Picard MH, Liao R, Rosenzweig A. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(25):22896. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200347200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Duronio V. Biochem J. 2008;415(3):333. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kops GJ, de Ruiter ND, De Vries-Smits AM, Powell DR, Bos JL, Burgering BM. Nature. 1999;398(6728):630. doi: 10.1038/19328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Biggs WH, III, Meisenhelder J, Hunter T, Cavenee WK, Arden KC. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96(13):7421. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.13.7421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Feng J, Park J, Cron P, Hess D, Hemmings BA. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(39):41189. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406731200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huston E, Lynch MJ, Mohamed A, Collins DM, Hill EV, MacLeod R, Krause E, Baillie GS, Houslay MD. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(35):12791. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805167105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Azzi M, Charest PG, Angers S, Rousseau G, Kohout T, Bouvier M, Pineyro G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(20):11406. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1936664100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yi XP, Zhou J, Baker J, Wang X, Gerdes AM, Li F. Anat Rec A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol. 2005;282(1):13. doi: 10.1002/ar.a.20143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scott MG, Le Rouzic E, Perianin A, Pierotti V, Enslen H, Benichou S, Marullo S, Benmerah A. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(40):37693. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207552200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Muraski JA, Fischer KM, Wu W, Cottage CT, Quijada P, Mason M, Din S, Gude N, Alvarez R, Jr, Rota M, Kajstura J, Wang Z, Schaefer E, Chen X, MacDonnel S, Magnuson N, Houser SR, Anversa P, Sussman MA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(37):13889. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709135105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang Y, Wang Z, Li X, Magnuson NS. Oncogene. 2008;27(35):4809. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grandori C, Gomez-Roman N, Felton-Edkins ZA, Ngouenet C, Galloway DA, Eisenman RN, White RJ. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7(3):311. doi: 10.1038/ncb1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Raha D, Wang Z, Moqtaderi Z, Wu L, Zhong G, Gerstein M, Struhl K, Snyder M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(8):3639. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911315106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jendrisak J. J Biol Chem. 1980;255(18):8529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pokholok DK, Zeitlinger J, Hannett NM, Reynolds DB, Young RA. Science. 2006;31(5786):533. doi: 10.1126/science.1127677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lawrence MC, McGlynn K, Shao C, Duan L, Naziruddin B, Levy MF, Cobb MH. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(36):13315. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806465105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Clark A, Dean J, Tudor C, Saklatvala J. Front Biosci. 2009;14:847. doi: 10.2741/3282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]