To the Editor

Our understanding of EoE pathogenesis is incomplete, but repetitive antigen exposure plays a role in the majority of patients. Skin prick testing, serum IgE levels, and atopy patch testing in some centers have been used to guide dietary elimination, but there is insufficient data to suggest that they are superior to empiric elimination of common food triggers.1 Recent data suggest a possible association between EoE and elevated levels of total IgG4 (T-IgG4), and that IgG4 may be implicated in disease pathogenesis.2

The role of IgG4 in EoE is unclear. Clayton et al2 showed that esophageal IgG4 deposits in EoE derive from dense plasma cell infiltrates in the lamina propria. Moreover, data from one study noted that intrasquamous deposits of IgG4 may distinguish patients with GERD versus EoE.3 These observations suggest potential associations between EoE and IgG4-related diseases. Nontheless, food-specific IgG4 has also been shown to inhibit basophil and mast cell responses4; indeed, food-specific IgG4:IgE ratios have been identified as markers of sustained unresponsiveness5 and oral tolerance.6 We speculate that IgG4 may be a marker of epitheial disruption produced initially to attenuate IgE-mediated disease but that, ultimately, results in a pro-inflammatory process in susceptible atopic hosts. Evidence for this concept may be supported by the development of EoE in some subjects undergoing oral immunotherapy.7

Since common food allergens are primary triggers of EoE, the aim of this study was to examine the role of food-specific IgG4 in the pathogenesis of EoE. We hypothesized that food-specific IgG4 (FS-IgG4) levels would be elevated in subjects with active EoE compared to controls, decrease with successful dietary elimination, and correlate with known food triggers.

We performed a case control study of 20 adult EoE subjects and 10 non-eoE controls using prospectively banked specimens from the University of North Carolina EoE Registry and Biobank. Details regarding recruitment, specimens and data collection have been published previously.8 Diagnosis of active EoE was defined by consensus guidelines.9 Non-EoE controls were subjects with dysphagia or GERD who did not meet histologic critieria for EoE. Subjects with PPI-REE were excluded. Subjects diagnosed with EoE were treated with a six food elimination diet (SFED) where dairy, egg, wheat, soy, peanut/tree nuts, and seafood were eliminated in addition to suspected dietary triggers based on clinical history. Eleven subjects demonstrated histologic resolution of esophageal eosinphilia (<15 eos/hpf) after 6–8 weeks of dietary elimination and were classified as diet responders. The 9 remaining subjects were classified as non-responders. Clinical food triggers were identified by serial reintroduction of individual food groups followed by repeat endoscopy and biopsy at approximately 6 week intervals. Figure E1 illustrates the study design. We measured T-IgG4 and FS-IgG4 levels for peanut, soy, egg white, casein and wheat by ELISA in paired plasma and esophageal homogenates at baseline and following dietary elimination. Details regarding the study population, methods for IgG4 measurement, and statistical analysis are detailed in this article’s online respository at jacionline.org.

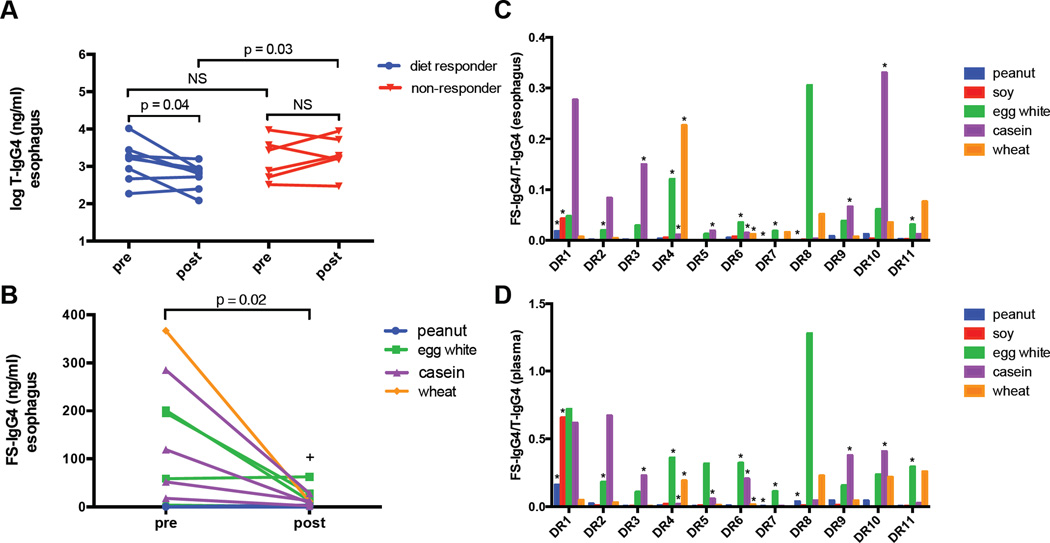

Table E1 details the demographics and clinical characteristics of the study population. At baseline, subjects with EoE demonstrated signficantly higher levels of T-IgG4 and FS-IgG4 in the esophagus in comparison to non-EoE controls (Table 1). Similar results were seen in the plasma, although plasma T-IgG4 did not differ significantly in EoE subjects. Significant differences were not observed for baseline T-IgG4 or FS-IgG4 levels when non-responders were compared to diet responders. Linear regression analysis of T-IgG4 and FS-IgG4 measurements in all subjects revealed positive correlations between esophageal FS-IgG4 levels and those seen in the plasma (Fig E2). Following dietary elimination, esophageal T-IgG4 declined significantly in responders (p=0.04) (Fig1, A), but not among non-responders. Additionally, post-elimination T-IgG4 levels were significantly lower in the responder group than the non-responder group (p=0.03). In diet-responders with identified triggers, we observed significant declines in esophgeal, but not serum, FS-IgG4 for all trigger foods (p = 0.02) (Fig 1, B). Interestingly, the one subject that demonstrated a slight increase in egg white-specific IgG4 was consuming baked egg at the time of follow-up biopsy.

Table I.

Baseline absolute IgG4 levels in EoE subjects and controls

| Controls (n = 10) |

EoE cases (n = 20) |

p† | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Esophageal biopsies (median, IQR) |

|||

| Peanut | 0.01 (0.01–0.50) | 4.05 (0.39–14.5) | 0.003 |

| Soy | 0.01 (0.01–0.01) | 2.12 (0.12–4.82) | < 0.001 |

| Egg white | 2.88 (0.01–12.7) | 61.4 (21.1–147.3) | < 0.001 |

| Casein | 0.67 (0.01–3.78) | 55.8 (5.87–271.5) | < 0.001 |

| Wheat | 1.10 (0.01–3.82) | 19.9 (5.13–184.6) | < 0.001 |

| Total | 469 (210–848) | 1847 (551–3487) | 0.008 |

| Plasma (median, IQR) | |||

| Peanut | 609.0 (153–1731) | 2324 (703.9–18709) | 0.04 |

| Soy | 54.8 (0.01–1204) | 1141 (436.9–3549) | 0.02 |

| Egg white | 16400 (1683–78833) | 84147 (30720–151476) | 0.01 |

| Casein | 2928 (384–7232) | 22316 (5113–123456) | 0.01 |

| Wheat | 4984 (298–10388) | 14773 (4486–119263) | 0.04 |

| Total | 276839 (101755–725261) | 441092 (146954–747240) | 0.65 |

Total and antigen-specific IgG4 measurements are reported in ng/ml

comparisons of medians by Wilcoxon rank-sum

Figure 1. Esophageal IgG4 is elevated in EoE subjects and decreases in response to dietary elimination.

(A) Esophageal T-IgG4 levels decrease after dietary elimination in diet responders but not in non-responders. (B) Esophageal FS-IgG4 levels to known triggers decrease significantly following dietary elimination. Baseline esophageal (C) and plasma (D) FS-IgG4/T-IgG4 ratios for diet responders with identified triggers

+ Denotes a subject that continued to consume baked egg (B).

* Denote confirmed food triggers (C, D)

Among the eleven diet responders, baseline esophageal and plasma FS-IgG4:T-IgG4 ratios were elevated for a majority of trigger foods (Fig 1, C and D). Some subjects with marked elevations of FS-IgG4 did not have corresponding clinical triggers. Of note, the one subject with soy as a trigger was the only subject with elevated esophageal and plasma levels of soy-specific IgG4. We were not able to derive predictive thresholds of FS-IgG4 for invidual food triggers given the small size of our cohort and large variations in IgG4 levels among subjects. Interestingly, some EoE subjects had persistently elevated T-IgG4 levels despite dietary elimination. While this may reflect non-adherence it may also be due to the presence of IgG4 to food allergens which have not been successfully identified, aeroallergens or other environmental triggers of EoE.

While interpreting our results, we acknowledge certain limitations. This is a single center, exploratory study of adult subjects; therefore, the results cannot be generalized to children. The sample size is also relatively small and insufficiently powered to make definitive comparisons between responders and non-responders or draw conclusions regarding FS-IgG4 as a marker of specific food triggers. Because the majority of esophageal IgG4 levels were only measured from a single biopsy specimen, it is possible that more focal deposits of IgG4 were not detected. Moreover, we did not assess food specific IgE responses. However, these limitations are balanced by a number of strengths including the study’s prospective design, utilization of banked samples collected, stored and processed in a uniform fashion for all subjects, detailed clinical and dietary elimination information, and blinded analysis of matched tissue and plasma samples.

In summary, we observed in this small sample of adult EoE subjects that T-IgG4 and FS-IgG4 are elevated in the esophagus compared to non-EoE controls. We found that when food triggers are eliminated, esophageal total and FS-IgG4 levels decrease in diet responders; although, these trends are not clearly seen in plasma. The presence of FS-IgG4 in the esophagus of EoE subjects suggests that chronic antigen exposure in an atopic individual appears to be associated with an antigen specific-IgG4 response that may contribute to the pathogenesis of EoE.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

none

Declaration of funding: Funded by the National Institutes of Health T32 AI007062 (BLW); NIH K23 DK090073 (ESD); T32 DK007634 (WAW). This project was also supported in part by a Translational Team Science Award with funding provided by the UNC School of Medicine and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), National Institutes of Health, through Grant Award Number UL1TR001111

Abbreviations used

- DR

diet responders

- eos/hpf

eosinophils per high power field

- EoE

eosinophilic esophagitis

- FS-IgG4

food-specific IgG4

- GERD

gastroesophageal reflux disease

- NR

non-responders

- PPI

proton pump inhibitor

- SFED

six food elimination diet

- T-IgG4

total IgG4

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Henderson CJ, Abonia JP, King EC, Putnam PE, Collins MH, Franciosi JP, et al. Comparative dietary therapy effectiveness in remission of pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:1570–1578. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clayton F, Fang JC, Gleich GJ, Lucendo AJ, Olalla JM, Vinson LA, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis in adults is associated with IgG4 and not mediated by IgE. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:602–609. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zukerberg L, Mahadevan K, Selig M, Deshpande V. Esophageal intrasquamous IgG4 deposits: An Adjunctive Marker to Distinguish Eosinophilic Esophagitis from Reflux Esophagitis. Histopathology. 2015 doi: 10.1111/his.12892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akdis M, Akdis CA. Mechanisms of allergen-specific immunotherapy: multiple suppressor factors at work in immune tolerance to allergens. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:621–631. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.12.1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vickery BP, Scurlock AM, Kulis M, Steele PH, Kamilaris J, Berglund JP, et al. Sustained unresponsiveness to peanut in subjects who have completed peanut oral immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133:468–475. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Du Toit G, Roberts G, Sayre PH, Bahnson HT, Radulovic S, Santos AF, et al. Randomized trial of peanut consumption in infants at risk for peanut allergy. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:803–813. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lucendo AJ, Arias A, Tenias JM. Relation between eosinophilic esophagitis and oral immunotherapy for food allergy: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014;113:624–629. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2014.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dellon ES, Rusin S, Gebhart JH, Covey S, Higgins LL, Beitia R, et al. Utility of a Noninvasive Serum Biomarker Panel for Diagnosis and Monitoring of Eosinophilic Esophagitis: A Prospective Study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:821–827. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liacouras CA, Furuta GT, Hirano I, Atkins D, Attwood SE, Bonis PA, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: updated consensus recommendations for children and adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:3–20 e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.02.040. quiz 1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.