Abstract

Objectives

This study examined whether acculturation to American culture, maintenance of Chinese culture, and their interaction predicted Chinese immigrant parents’ psychological adjustment and parenting styles. We hypothesized that American orientation would be associated with more positive psychological well-being and fewer depressive symptoms in immigrant mothers, which in turn would be associated with more authoritative parenting and less authoritarian parenting. The examination of the roles of Chinese orientation and the interaction of the two cultural orientations in relation to psychological adjustment and parenting were exploratory.

Methods

Participants were 164 first-generation Chinese immigrant mothers in the U.S. (Mage = 37.80). Structural equation modeling was used to examine the direct and indirect effects of acculturation on psychological adjustment and parenting. Bootstrapping technique was used to explore the conditional indirect effects of acculturation on parenting as appropriate.

Results

American orientation was strongly associated with positive psychological well-being, which was in turn related to more authoritative parenting and less authoritarian parenting. Moreover, American and Chinese orientations interacted to predict depressive symptoms, which were in turn associated with more authoritarian parenting. Specifically, American orientation was negatively associated with depressive symptoms only at mean or high levels of Chinese orientation.

Conclusions

Results suggest acculturation as a distal contextual factor and psychological adjustment as one critical mechanism that transmits the effects of acculturation to parenting. Promoting immigrant parents’ ability and comfort in the new culture independently or in conjunction with encouraging biculturalism through policy intervention efforts appear crucial for the positive adjustment of Chinese immigrant parents and children.

Keywords: acculturation, Chinese immigrants, depressive symptoms, psychological well-being, parenting style

Chinese immigrant parents in the U.S. need to reconcile cultural differences between their heritage Chinese culture and the mainstream American culture in every aspect of their adaptation to the life in the U.S., including in their parenting (Cheah, Leung, & Zhou, 2013). The process of cultural and psychological changes that take place as a result of contact between two or more cultural groups and their individuals is called acculturation, which may entail changes in one's behavioral repertoire, values, attitudes, identity, and/or maintenance of one's culture of origin (Berry, 2005, 2009). The current study focused on the direct and indirect associations between the behavioral acculturation of Chinese immigrant mothers in the U.S. and their parenting styles and practices.

The various acculturation processes can also be characterized by how frequently individuals actively engage in the traditions, norms, and practices of the mainstream or heritage culture (Tsai & Chentsova-Dutton, 2002; Ying, Lee, & Tsai, 2000). When mainstream and heritage cultural orientations are considered simultaneously, different acculturation strategies are possible: assimilation (orientation towards the mainstream culture only), separation (orientation towards the heritage culture only), integration (orientation towards both cultures), and marginalization (orientation towards neither culture) (Berry, 1997, 2005; Berry, Phinney, Sam, & Vedder, 2006). Previous studies have been limited due to the use of unilinear acculturation measure or examining only one of the two dimensions within a single study, despite the wide consensus on the benefits of using bilinear assessments of acculturation to capture dual cultural orientations (Costigan & Su, 2004; Ryder, Alden, & Paulhus, 2000). Moreover, researchers who included both dimensions typically utilized the cut-off score (e.g., mean, median, or the scale mid-point) to group participants, in order to create four acculturation styles (e.g., Eyou, Adair, & Dixon, 2000; Der-Karabetian & Ruiz, 1997). The problem is that the cut-off score approach cannot capture the varying degree of the two cultural orientations (Chia & Costigan, 2006). In addition, arbitrarily dividing participants who are slightly below and above the cut-off score into two different acculturation groups may be problematic because individuals with moderate scores on the cultural orientations may converge into additional acculturation patterns (Coatsworth, Maldonado-Molina, Pantin, & Szapocznik, 2005). Therefore, the current study examined both American and Chinese orientations using a bilinear measure and explored the interaction between the two cultural orientations, instead of the cut-off score approach, to better capture the role of acculturation (strategies) in Chinese immigrant parents’ adjustment and parenting.

Acculturation and Parenting

Researchers have proposed that parenting may change as acculturating immigrant parents adopt attitudes and behaviors of the mainstream culture (Bornstein & Cote, 2004; Farver & Lee-Shin, 2000). The present study focused on two most widely studied parenting styles: authoritative and authoritarian parenting identified by Baumrind (1967). Some researchers have critiqued the applicability of Baumrind's parenting styles to Asian parents (e.g., Chao, 1994). However, the authoritative and authoritarian parenting styles have been found to have important implications on child development in both independent (e.g., United States) and interdependent (e.g., China) cultures (Baumrind, Larzelere, & Owens, 2010; Chen, Dong, & Zhou, 1997; Sorkhabi, 2005), as well as Chinese immigrant families (Cheah, Leung, Tahseen, & Schultz, 2009). American culture values independence, assertiveness, and autonomy (Greenfield, Keller, Fuligni, & Maynard, 2003). Thus, authoritative parenting, characterized by warmth and responsiveness, respect for and encouragement of children's autonomy, and discipline through reasoning and induction, is highly endorsed. In contrast, Chinese culture emphasizes interdependence and emotional restraint to maintain harmonious interpersonal relationships as well as filial piety affording great authority and respect to parents (Chao & Tseng, 2002; Kim & Sherman, 2007; Wu, 1996). Hence, compared to their American counterparts, Chinese parents tend to use more authoritarian parenting that is characterized by physical coercion, verbal hostility, and frequent use of punitive discipline strategies, and less authoritative parenting (Darling & Steinberg, 1993; Wu et al., 2002). Several recent studies indicated that Chinese immigrant mothers in the U.S. also endorsed authoritative parenting or autonomy-supportive practices to support their children's positive development (e.g., Cheah et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2014; Liew Kwok, Chang, Chang, & Yeh, 2014; Kim, Wang, Orozco-Lapray, Shen, & Murtuza, 2013). Given the cultural differences in child socialization beliefs, it is reasonable to believe that, for Chinese immigrant parents, higher acculturation to American culture would be associated with more authoritative parenting and less authoritarian parenting whereas higher acculturation to Chinese culture would be associated with more authoritarian parenting and less authoritative parenting.

However, empirical evidence supporting the direct associations between acculturation and parenting practices has been inconsistent. Whereas some researchers found no associations between acculturation and parental control (Chuang, 2006) or the use of physical discipline (Lau, 2010) among Chinese immigrant parents in North America, others (e.g., Liu, Lau, Chen, Dinh, & Kim, 2009) reported that the American orientation was related to higher levels of maternal monitoring and lower levels of harsh discipline in Asian-American parents. Different measurements of acculturation across studies may partly explain the inconsistent findings (Ho, 2014). More importantly, acculturation may be indirectly associated with parenting through potential mediating mechanisms that have not been fully explored in the literature.

In this study, we examined one potential mediator, maternal psychological adjustment, in the associations between acculturation and maternal parenting. According to Belsky's (1984) process model, parents’ psychological functioning is the most influential factor contributing to parenting, and may mediate the effects of contextual stress or support on parenting behavior. Facing different cultural norms and resulting cultural conflict may be sources of stress that arises uniquely from the acculturation process, which can influence the adjustment of immigrants (e.g., Oh, Koeske, & Sales, 2002). We considered acculturation as one contextual source of stress or support for Chinese immigrant parents. In the following sections, we reviewed studies on the acculturation to psychological adjustment link (Path a), the psychological adjustment to parenting link (Path b), and the currently available evidence on the mediating pathway (Path ab) where psychological adjustment mediates the associations between acculturation and parenting.

Acculturation and Psychological Adjustment

The associations between acculturation and psychological adjustment have been widely studied but whether each cultural orientation is related to favorable health outcomes remains inconclusive, partly due to the use of unilinear measures of acculturation in many studies (Schwartz et al., 2010). Theoretically, better English language skills and more social interactions with American people may provide immigrants with better employment opportunities and more positive self-evaluations but may also expose them to more discrimination situations. Similarly, exclusive dependence on speaking Chinese and interacting frequently with Chinese friends may lead to underemployment in immigrants but may also increase their ethnic pride and co-ethnic social support network. In a recent meta-analysis, Yoon, Langrehr, and Ong (2011) found a small but significant negative association between acculturation towards the host culture and psychological distress/depressive symptoms but did not find a significant relation between acculturation to heritage culture and psychological outcomes. Another meta-analysis conducted by Gupta, Leong, Valentine, and Canada (2013) also revealed a small but significantly negative relation between acculturation towards the American culture and depressive symptoms, and a non-significant overall association between acculturation towards the Asian culture and depressive symptoms. It should be noted that Asians are less likely to report depressive symptomatology than European Americans even if they actually experience similar levels of depression (Wong, Tran, Kim, Kerne, & Calfa, 2010), probably resulting in an attenuated estimate between cultural orientations and depressive symptoms. By including both negative and positive health outcomes, Yoon et al. (2013) meta-analyzed 325 studies and found that acculturation to the host culture was favorably associated with both negative mental health (e.g., less depression and psychological distress) and positive mental health (e.g., more self-esteem and satisfaction with life), although the specific types of mental health outcomes differed. However, maintenance of heritage culture was only favorably associated with positive psychological functioning (e.g., self-esteem) and was unfavorably related to negative mental health (e.g., more anxiety), suggesting that each cultural orientation may have differential implications on negative versus positive psychological adjustment.

With regard to acculturation strategies, Nguyen and Benet-Martínez (2013) conducted a meta-analysis on biculturalism (the integration acculturation strategy) and showed that integrated individuals tended to be significantly better adjusted than those who were oriented to only one culture. Importantly, the biculturalism-adjustment association was stronger for Latin, Asian, and European participants than for African or Indigenous participants. An empirical study among Chinese-American mothers (Tahseen & Cheah, 2012) also found that mothers who participated in both cultures exhibited better mental health than those with a separated acculturation strategy. In sum, the positive effects of acculturation towards the mainstream culture are generally found whereas findings on the effects of the maintenance of the heritage culture are less clear. In addition, due to the limitations of the cut-off score approach that was primarily used in previous studies to create acculturation strategies, empirical studies using more appropriate approaches, such as the interaction approach proposed here, are warranted.

Psychological Adjustment and Parenting

A large body of literature has indicated the significant role of parental psychological adjustment in shaping parenting (see Lovejoy, Graczyk, O'Hare, & Neuman, 2000; Wilson & Durbin, 2010 for meta-analyses). Most previous research focused on the deleterious effects of poor mental health in predicting parenting. For example, depressive symptoms were found to be associated with more maladaptive parenting, including harsher and inconsistent parenting (Baydar, Reid & Webster-Stratton, 2003), more restrictive and coercive parenting (Bor & Sanders, 2004; Gutman, Fridel, & Hitt, 2003), and more neglectful behaviors in lower economic status mothers of diverse ethnic background in the U.S. (Turney, 2011). However, the associations between depressive symptoms and positive parenting were not consistently found (Baydar et al., 2003; Costigan & Koryzma, 2011).

In addition, few studies have examined the beneficial effects of positive psychological well-being (e.g., self-acceptance, personal growth) on more supportive or less controlling parenting especially among young children. Cheah et al. (2009) examined Chinese immigrant mothers with young children and found that psychological well-being was associated with more authoritative parenting behaviors when mothers experienced low levels of parenting stress. Mothers with higher self-acceptance, a more positive view on life, and greater sense of environmental mastery were found to be more likely to demonstrate sensitive parenting and less likely to prefer punitive punishment strategies (Meyers & Battistoni, 2003). Based on the limited available evidence, positive psychological functioning seems to be favorably associated with both negative and positive parenting. Due to the general lack of studies on positive psychological well-being and inconsistent findings regarding the role of depressive symptoms, more research systematically examining each adjustment-parenting link is needed.

Acculturation, Psychological Adjustment, and Parenting

Few studies have examined the mediating role of psychological adjustment in the links between cultural orientations and parenting. White, Roosa, Weaver, and Nair (2009) investigated the mediating role of depressive symptoms in the association between one domain of acculturative stress (English competency pressures) and parenting in Mexican American families. Their findings reflected inconsistent mediation, i.e., a positive direct effect of English competency pressures on mothers’ warmth plus a negative indirect effect on warmth and consistent discipline behavior through depressive symptoms, with a total positive effect of English competency pressures on warmth. The authors explained that when mothers experience a contextual stressor associated with living in another culture, they may try to overcompensate for these perceived pressures on their children by offering high levels of warmth.

Kim, Shen, Huang, Wang, and Orozco-Lapray (2014) examined whether Chinese American parents of adolescents’ acculturation was related to their parenting practices through the mediating role of parents’ bicultural management difficulty and depressed mood. They found that mothers’ American orientation (but not Chinese orientation) was related to less bicultural management difficulty, which in turn was related to fewer depressive symptoms and then less punitive parenting and inductive reasoning. These studies provided some evidence for both the more predictive role of American versus Chinese orientation and depressive symptoms as an important mechanism linking acculturation to parenting. Much remains unknown, however, regarding whether acculturation is associated with parenting through negative mental health in immigrant parents with young children, and whether positive psychological functioning mediates some of the acculturation-parenting links.

According to the dual continuum model, positive mental health and mental illness belong to two correlated but separated entities among the population (Keyes, Dhingra, & Simoes, 2010). Keyes (2002) introduced the terms “flourishing” and “languishing” to describe the presence of positive psychological functioning and mental illness respectively. Some processes related to positive well-being can be quite distinct from those concerning mental illness (Huppert & Whittington, 2003; Winzer, Lindblad, Sorjonen, & Lindberg, 2014). Given that cultural orientations may be differentially related to negative (e.g., depression) versus positive mental health (e.g., self-esteem) (e.g., Yoon et al., 2013), which may also correlate differentially with (positive) parenting behavior (e.g., Meyers & Battistoni, 2003), it is worthwhile to examine negative and positive psychological adjustment as separate mediating mechanisms leading to both positive and negative parenting in the acculturation-parenting associations.

The Present Study

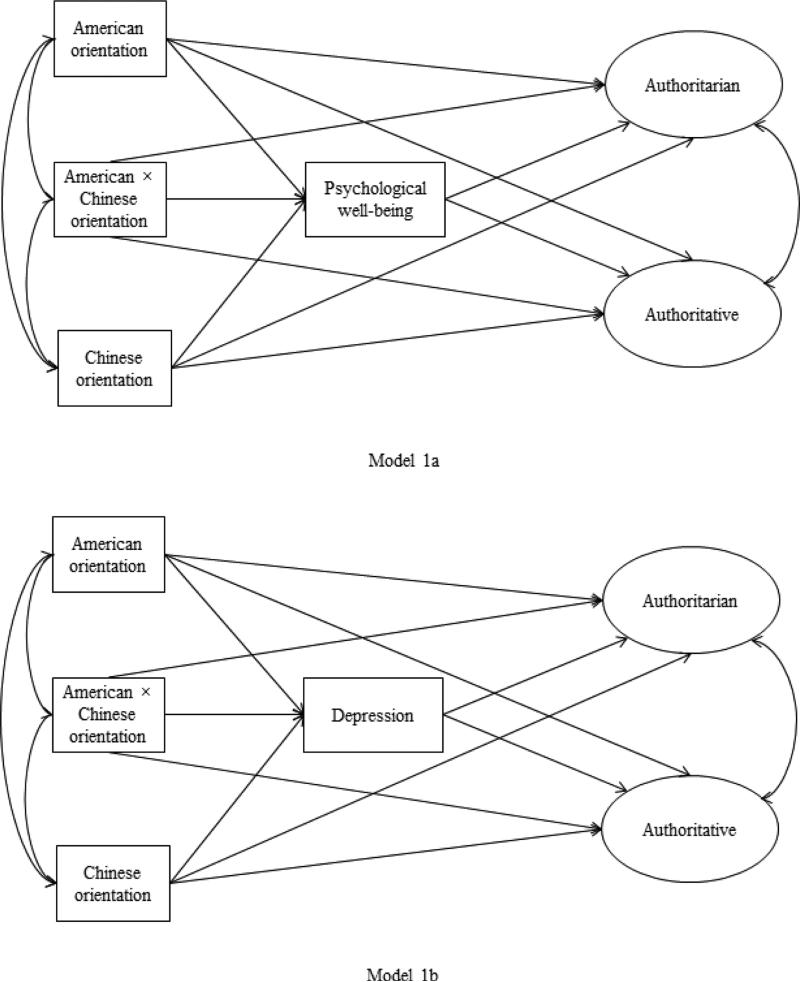

The primary goal of this study was to test the direct and indirect effects of maternal acculturation on parenting styles through maternal psychological well-being and depressive symptoms. Despite the advantages of a multiple mediator model in terms of providing unique effects of each mediator, two separate mediation models were estimated because depressive symptoms and psychological well-being are distinct but not completely independent constructs as positive and negative aspects of individuals’ psychological adjustment (Costigan & Koryzma, 2011). The conceptual overlap and thus the corresponding collinearity between the two mediator variables may attenuate the specific indirect effects and lead to incorrect conclusions on whether each variable serves as a mediator (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). More importantly, as stated earlier, the mediator variables may be differentially related to each cultural orientation (Yoon et al., 2013) and parenting outcome (Meyers & Battistoni, 2003); thus, unique mediating mechanisms may be revealed by testing separate mediation models. In both models of depressive symptoms as M (Model 1a) and psychological well-being as M (Model 1b), American orientation, Chinese orientation, and their product were included as antecedent variables (Xs) and latent authoritarian and authoritative parenting styles were included as criterion variables (Ys) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The proposed moderated mediation model

Note: Model 1a: The conceptual model with maternal psychological well-being as the mediator. Model 1b: The conceptual model with maternal depressive symptoms as the mediator.

We hypothesized that higher levels of American orientation would be related to higher levels of psychological well-being (and lower levels of depressive symptoms), which in turn would predict less use of authoritarian parenting and more use of authoritative parenting. Due to the inconsistent findings in the literature, we did not have specific hypotheses for the effects of Chinese orientation on immigrant mothers’ psychological adjustment or the direct effects of American and Chinese orientations on immigrant mothers’ parenting. The examination of the interaction between the two cultural orientations was also exploratory due to a lack of previous studies using this method to test acculturation strategies. However, we did expect that the integrated acculturation strategy would be most adaptive. That is, mothers who were high on both cultural orientations would report the best adjustment outcomes.

Methods

Participants

First-generation Chinese immigrant mothers (N = 164, Mage = 37.80, SD = 4.46) with 3- to 6-year-old children (Mage = 4.52, SD = 0.91, 53.6% males) participated in the present study. The mothers had been in the U.S. for an average of 10.75 years (SD = 6.18). Almost all of the mothers were married (99.4%) and first-generation Chinese immigrants (99.3%). Mothers immigrated to the U.S. for educational and work reasons (48.7%), to accompany their spouse or join extended family in the U.S. (43.4%), and/or to enhance life experiences and for a better lifestyle (6.6%). The families were middle-class, and almost all of the mothers had at least a bachelor's degree (93.4%). About 17.6% of the mothers did not provide information on their occupations. For those who reported their occupations, 24.0% of the mothers were housewives, 13.8%, were smaller business owners, managers, minor professionals, and 44.6% of the mothers were administrators, lesser professionals, proprietor of medium-sized business or higher executive, proprietor of large businesses, or major professionals, based on the occupational codes by Hollingshead (1975) that were updated by Bornstein, Hahn, Suwalsky, and Haynes (2003).

Procedures

The mothers were recruited primarily from Chinese schools, churches, daycare centers, and other organizations in the Baltimore-Washington Metropolitan area through word of mouth, fliers, and recruitment presentations. Data collection was conducted during a home visit by two or more trained research assistants who were fluent in the parents’ preferred language or dialect (English, Mandarin, or Cantonese). Written consent was first obtained from the mothers, who completed the questionnaires in the written language of their choice. Participants received $40 and project newsletters for their time. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the University Institutional Review Board.

Measures

All the following measures have been used previously in Chinese or Chinese immigrant samples and demonstrated adequate reliability and validity (e.g., Chan, 1991; Chen et al, 2015; Iwamoto & Liu, 2010; Lee et al., 2014).

Acculturation

The Cultural and Social Acculturation Scale (CSAS; Chen & Lee, 1996) was administered to measure participants’ orientations to Chinese and American cultures. The CSAS is a bilinear scale that includes two separate subscales reflecting individuals’ cultural orientation to both heritage and mainstream cultures in the domains of language proficiency, living styles/media use, and social relationships. Example items include: “How often do you spend time with your American (or Chinese) friends?”, “How well do you speak in English (Chinese)?”, and “Do you celebrate American (or Chinese) festivals?” Mothers reported on the frequency of involvement in the described behaviors or degree of proficiency in the language using a five point Likert-type scale (e.g., 1 = “almost never” to 5 = “more than once a week” or 1 = “extremely poor” to 5 = “extremely well”). A total of eleven items for each scale were averaged to create the mean score of mothers’ behavioral acculturation towards the mainstream and Chinese cultures potentially ranging from 1 to 5. The Cronbach's α for the American and Chinese orientations were .75 and .65, respectively, in this study.

Psychological well-being

The Psychological Well-Being Scale (PWB; Ryff & Keyes, 1995) was administered to assess mothers’ overall psychological well-being across six areas of their lives, including self-acceptance, positive relationships, autonomy, environmental mastery, feelings of having a purpose in life, and personal growth. Participants rated how much they agreed with statements describing ways in which people might think about their lives on a seven point Likert-type scale (1 = “strongly disagree” to 7 = “strongly agree”). Example items include: “I judge myself by what I think is important, not by what others think is important.”, “I am quite good at mastering the many responsibilities of my daily life, and “I feel I am in charge of the situation in which I live.” The mean scores of the 18 items were calculated. The Cronbach's α was .78 in this study.

Depressive symptoms

The Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI-II; Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996) was used to measure immigrant mothers’ symptoms and characteristic attitudes of depression in the previous two weeks, such as sadness, pessimism, loss of pleasure, self-criticalness, suicidal thoughts or wishes, agitation, loss of interest, concentration difficulties, and tiredness or fatigue. The severity of each individual emotion item was rated on a four point Likert-type scale from 0 (e.g., “I do not feel sad”) to 3 (e.g., “I am so sad or unhappy that I can't stand it”). The total depressive symptomatology score was calculated by summing the 21 items, which can potentially range from 0 to 63. The Cronbach's α was .86 in this study.

Parenting styles

The Parenting Styles and Dimensions Questionnaire (PSDQ; Wu et al., 2002) was used to measure mothers’ endorsement of authoritative and authoritarian parenting practices. The authoritative parenting subscale was comprised of warmth expressions (7 items, α = .78; e.g. “I give comfort and understanding when my child is upset”), reasoning (4 items, α = .70; e.g. “I give my child reasons why rules should be obeyed”), and autonomy granting (4 items, α = .64; e.g. “I allow my child to give input into family rules”). The authoritarian parenting subscale included physical coercion (5 items, α = .75; e.g. “I grab my child when being disobedient”), verbal hostility (3 items, α = .58; e.g. “I scold or criticize when my child's behavior doesn't meet my expectations”), and punitive practices (3 items, α = .49; e.g. “I punish by putting my child off somewhere alone with little if any explanations”). Mothers reported on how often they exhibited each behavior on a five point Likert-type scale (1 = never to 5 = always). Mean scores for each of the six behavioral indexes were calculated, which can potentially range from 1 to 5. These scores were used to construct the latent factors of authoritarian and authoritative parenting styles. The reliability estimate was .87 for the overall authoritative parenting style, and .78 for the overall authoritarian parenting style.

Statistical Analyses

To examine the two mediation models, structural equation modeling (SEM) was used instead of the causal steps approach by Baron and Kenny (1986), which has been criticized heavily on multiple grounds (Hayes, 2009). For example, the causal steps approach has the lowest power among the methods in detecting the mediating effect (Fritz & MacKinnon, 2007). Moreover, with the causal steps approach, there is no direct estimate or test for the size of the indirect effect of X on Y through M, and the Sobel test is usually conducted separately to test whether the indirect effect is significantly different from zero or not (Sobel, 1986). In contrast, the SEM approach provides the direct estimate and significance test of the indirect effects. Importantly, unlike the causal steps approach, the SEM framework does not require a detectable total effect of X on Y to examine X's indirect effect on Y through M so that some potentially important mechanisms can be captured (Hayes, 2009; MacKinnon, Krull, & Lockwood, 2000; Shrout & Bolger, 2002). Consistent with many others (e.g., Preacher & Hayes, 2008), mediating and indirect effects were used interchangeably in this paper.

The SEM models were analyzed using Mplus 7 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2012). The Mardia multivariate skewness and kurtosis tests were both significant (ps < .001), indicating the violation of multivariate normality assumption, thus the robust maximum likelihood (MLR) estimator was used for SEM analyses. The MLR estimator provides standard errors and χ2 test statistic that are robust to non-normality and is also recommended for small and medium sample sizes (Yuan & Bentler, 2000; Muthén & Asparouhov, 2002). To evaluate the overall model fit, the robust scaled chi-square statistic (S-Bχ2), the comparative fit index (CFI), the root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA), and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) were taken into consideration. Good model fit was indicated by CFI >.95, RMSEA <.06, and SRMR <.08 (Hu & Bentler, 1998). Acceptable model fit was evidenced by CFI >.90, RMSEA <.08, and SRMR <.10 (Bollen, 1989; Loehlin, 1998). When there was a significant moderated mediation, a bias-corrected bootstrapping approach was adopted to test the conditional indirect effects, which generated the confidence intervals for the conditional indirect effects through resampling 5,000 random samples (Preacher, Rucker, & Hayes, 2007). The null hypothesis of conditional indirect effect is rejected if the confidence interval does not contain 0.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Out of the total 1,640 scores (10 variables × 164 participants), there were 16 missing data (i.e., less than 1%). The full-information maximum likelihood estimation was used to handle the missing data (Enders, 2013). Correlations and descriptive statistics of the study variables were presented in Table 1. For all variables, higher scores represented higher levels of the construct. Based on the zero-order correlations, acculturation seemed largely uncorrelated with parenting practices. Only one (i.e., correlation between Chinese orientation and physical coercion) out of 12 correlations was statistically significant. Moreover, American orientation was significantly correlated with fewer depressive symptoms and more psychological well-being, whereas Chinese orientation was associated with more depressive symptoms and was not correlated with psychological well-being. Finally, psychological well-being was significantly correlated with less authoritarian parenting (physical coercion, verbal hostility, and punitive practices), and more authoritative parenting (warmth, reasoning, and autonomy granting practices). Depressive symptoms were positively correlated with authoritarian parenting but were not related to authoritative parenting practices. These correlations suggested that psychological adjustment especially positive psychological well-being may serve an important mediator through which acculturation indirectly affected immigrant mothers’ parenting styles.

Table 1.

Correlations and Descriptive Statistics of Study Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. American orientation | – | 2.98 | 0.64 | ||||||||||||

| 2. Chinese orientation | .18* | – | 3.67 | 0.55 | |||||||||||

| 3. Depressive symptoms | −.25** | .17* | – | 5.90 | 6.28 | ||||||||||

| 4. Psychological well-being | .37 | .004 | −.36** | – | 5.21 | 0.61 | |||||||||

| 5. Physical coercion | .09 | .31** | .17* | −.24** | – | 1.73 | 0.55 | ||||||||

| 6. Verbal hostility | .02 | .04 | .25** | −.26** | .44** | – | 1.93 | 0.51 | |||||||

| 7. Punitive | −.03 | −.02 | .17* | −.17* | .36** | .49** | – | 1.61 | 0.60 | ||||||

| 8. Warmth | .14 | .07 | −.09 | .34** | −.15 | −.24** | −.27** | – | 4.32 | 0.47 | |||||

| 9. Reasoning | .08 | .10 | .08 | .22** | −.04 | −.11 | −.15 | .66** | – | 4.15 | 0.56 | ||||

| 10. Autonomy granting | .09 | .14 | .03 | .25** | −.04 | −.17* | −.19* | .60** | .64** | – | 3.75 | 0.65 | |||

| 11. Maternal Education | .38** | −.01 | −.16* | .16* | −.05 | .06 | .01 | .04 | −.002 | .04 | – | 6.57 | 0.73 | ||

| 12. Child gender | −.04 | .11 | .12 | −.05 | .08 | −.05 | .13 | .01 | −.01 | .003 | −.01 | – | 1.46 | 0.50 | |

| 13. Child age | .03 | −.07 | −.06 | −.06 | .13 | .10 | .02 | −.07 | .02 | −.01 | .03 | −.04 | – | 4.52 | 0.91 |

| 14. Maternal age | .11 | −.03 | −.15 | .09 | .04 | −.01 | .06 | −.04 | −.02 | −.12 | .05 | −.15 | .34** | 37.80 | 4.46 |

Note:

p < .05.

p < .01.

SEM Analyses

Covariates

SEM analyses were conducted to test the two proposed mediation models where depressive symptoms and psychological well-being mediated the effects of the two cultural orientations on the latent authoritarian and authoritative parenting styles. Maternal age, maternal education, child age, and child gender were considered covariate variables in the proposed models. However, although maternal education was related to one of the predictor variables (i.e., mothers with higher levels of education were more acculturated to American culture), none of these covariates significantly predicted the mediator or outcome variables in the model (i.e., depressive symptoms, psychological well-being, authoritarian parenting, or authoritative parenting). Therefore, these covariate variables were not included in the final mediation models for parsimony and to avoid overcontrol (Little, 2013).

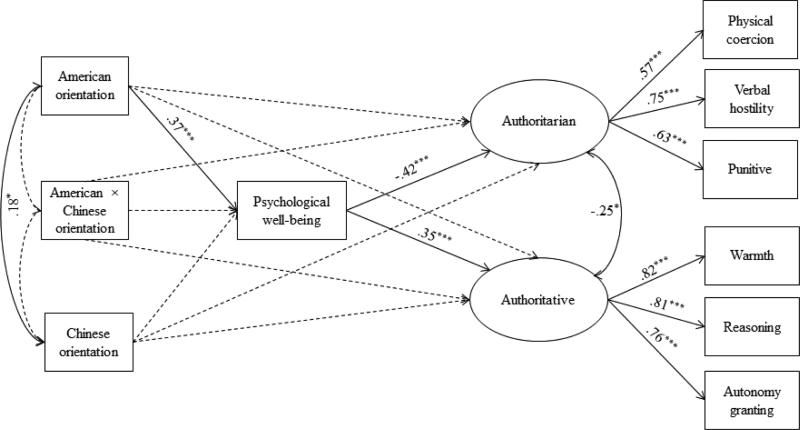

Psychological well-being as mediator

The model with psychological well-being as mediator (see Figure 2) achieved an acceptable model fit, χ2 (24, N = 164) = 39.33, p= .025, CFI = .95, SRMR = .05, and RMSEA = .06, 90% CI [.02, .10]. The standardized factor loadings of parenting styles indicators were similar to those in the model with depressive symptom as mediator. In predicting maternal psychological well-being (R2 = .14), there was a significant positive main effect of American orientation (b = 0.35, SE = 0.06, p < .001) but a non-significant main effect of Chinese orientation and interaction effect. Psychological well-being, in turn, negatively (b = −0.22, SE = 0.08, p = .006) predicted immigrant mothers’ authoritarian parenting style (R2 = .17) and positively (b = 0.22, SE = 0.06, p < .001) predicted their authoritative parenting style (R2 = .13). The indirect effect of American orientation on authoritarian parenting through psychological well-being was negative and significant (ab = −0.08, SE = 0.03, 95% CI [−0.15, −0.02]), and the indirect effect of American orientation on authoritative parenting style was positive and significant (ab = 0.08, SE = 0.03, 95% CI [0.03, 0.14]).

Figure 2.

The final mediation model with psychological well-being as the mediator

Note: Significant standardized coefficients were indicated in the figure and unstandardized structural coefficients were presented in text. Solid lines represent significant paths and dashed lines represent nonsignificant paths.

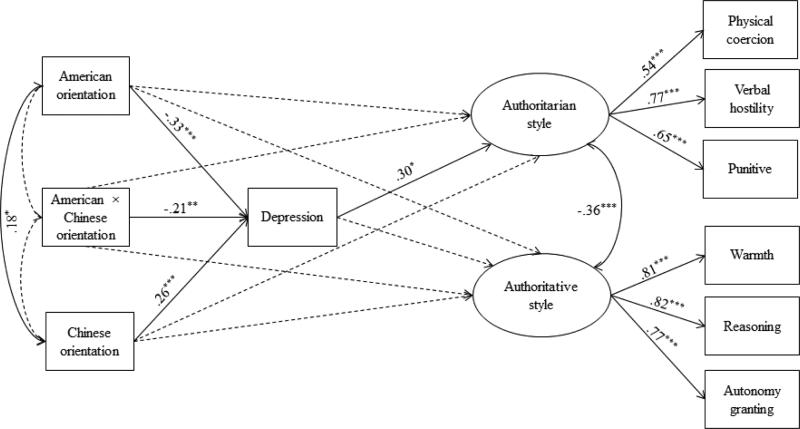

Depressive symptoms as mediator

The model with maternal depressive symptom as mediator (see Figure 3) also achieved an acceptable model fit, χ2 (24, N = 164) = 39.00, p= .027, CFI = .95, SRMR = .05, and RMSEA = .06, 90% CI [.02, .10]. All observed behavioral indicators of authoritarian and authoritative parenting styles had standardized factor loadings > .40, which are considered as evidence for sound psychometric properties of the measurement portion of the SEM model for sample size of 150 or more (Nelson, Hart, Yang, Olsen, & Jin, 2006; Steven, 1996). In predicting maternal depressive symptoms (R2 = .15), there was a significant negative main effect of American orientation (b = −3.26, SE = 0.75, p < .001) and a significant positive main effect of Chinese orientation (b = 2.96, SE = 0.98, p = .002). Importantly, these main effects were qualified by a significant interaction of American Orientation × Chinese Orientation (b = −3.27, SE = 1.14, p = .004). Depressive symptom, in turn, positively (b = 0.01, SE = 0.01, p = .037) predicted immigrant mothers’ authoritarian parenting (R2 = .10) but was not related to authoritative parenting. American orientation, Chinese orientation, and their interaction were not significant predictors of the parenting styles.

Figure 3.

The final mediation model with maternal depressive symptoms as the mediator

Note: Significant standardized coefficients were indicated in the figure and unstandardized structural coefficients were presented in text. Solid lines represent significant paths and dashed lines represent nonsignificant paths.

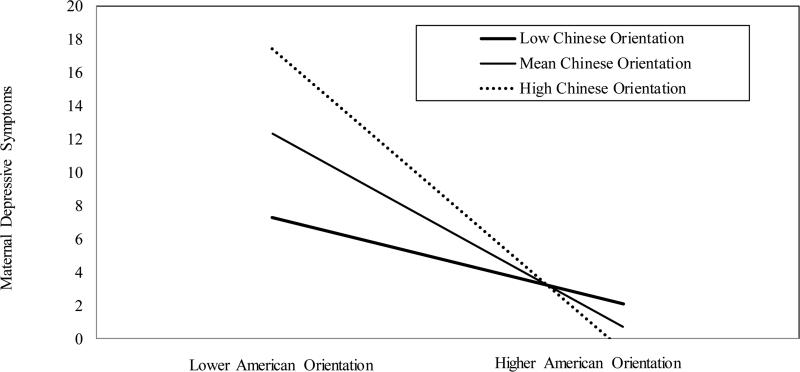

To probe the interaction effect (i.e., American Orientation × Chinese Orientation in predicting depressive symptoms), we performed simple slopes analyses (Aiken & West, 1991) to examine the effect of American orientation on maternal depressive symptoms at low (one SD below the mean), mean, and high (one SD above the mean) levels of Chinese orientation. As shown in Figure 4, at low levels of Chinese orientation, American orientation was not significantly related to maternal depressive symptoms (b = −1.45, p = .105), whereas at mean (b = −3.25, p < .001) and high (b = −5.06, p < .001) levels of Chinese orientation, more American orientation was significantly associated with lower levels of maternal depressive symptoms. Because of this interaction effect, the indirect effect of one cultural orientation on authoritarian parenting through maternal depressive symptoms may also be conditional on the other cultural orientation. To test the significance of the conditional indirect effects, we used the bias-corrected bootstrap confidence interval approach suggested by Preacher et al. (2007). We found that at low levels of Chinese orientation, the indirect effect of American orientation on authoritarian parenting through maternal depressive symptoms was not significant (ab = −0.02, SE = 0.02, 95% CI [−0.05, 0.001]), whereas at mean and high level of Chinese orientation, the indirect effect of American orientation on authoritarian parenting through maternal depressive symptoms was negative and significant (at mean level: ab = −0.05, SE = 0.03, 95% CI [−0.10, −0.01]; at high level: ab = −0.07, SE = 0.04, 95% CI [−0.15, −0.01]).

Figure 4.

American orientation and Chinese orientation interacted to predict maternal depressive symptoms

Note: At low levels of Chinese orientation, American orientation was not significantly related to maternal depressive symptoms (B = −1.45, p = .105), whereas at mean (B = −3.25, p < .001) and high (B = −5.06, p < .001) levels of Chinese orientation, more American orientation was significantly associated with less maternal depressive symptoms.

Discussion

The present study evaluated psychological adjustment as a mediator in the associations between acculturation and parenting styles among Chinese immigrant mothers in the U.S. Overall, the results indicated the different roles of American and Chinese cultural orientation in immigrant mothers’ psychological adjustment and differential implications of positive and negative psychological adjustment in relation to maternal parenting styles.

Cultural Orientations, Positive Psychological Well-Being, and Parenting

Consistent with previous studies that revealed orientation to the mainstream culture to be associated with better adjustment (e.g., Birman & Taylor-Ritzler, 2007; Costigan & Koryzma, 2011; Ryder et al., 2000; Takeuchi et al., 2002), we found that higher levels of American orientation were significantly related to more positive psychological well-being, and accordingly, more authoritative parenting and less authoritarian parenting that are adaptive for their preschool children's development (e.g., Cheah et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2014). The protective effects of acculturation towards American culture may be partially attributed to mothers’ better English language competence and familiarity with the Western lifestyle that enables them to engage more fully in the new cultural environment (Yu, Cheah, & Sun, 2015). These parents may also have greater access to social and parenting resources, gain more professional opportunities, and form more positive self-evaluation (Costigan & Koryzma, 2011), compared to parents who participate less in the mainstream culture. Such positive experiences can contribute to a greater sense of psychological well-being as reflected in more self-acceptance, positive relationships with others, autonomy, environmental mastery, feelings of having a purpose in life, and personal growth. Positive psychological well-being, in turn, enables parents to engage more in parenting that is considered effective and valued in the larger social-cultural context (Cheah et al., 2009). Specifically, these mothers were less likely to engage in coercive, hostile, and punitive parenting and more likely to use warmth, regulatory reasoning, and autonomy support perhaps because they have internalized the value of promoting autonomy and can form warm, trusting relationships with their children.

However, mothers’ behavioral participation in Chinese culture was not significantly associated with their positive psychological well-being, consistent with other research that have suggested stronger implications of immigrants’ orientation toward the mainstream culture for adjustment than their orientation towards the ethnic culture (Abbott et al., 2003; Hwang & Ting, 2008; Ryder et al., 2000). Behavioral involvement in the Chinese culture such as having high Chinese language proficiency, engaging in social activities with Chinese friends, and celebrating Chinese festivals, may not necessarily help or hinder immigrant parents from forming positive self-evaluation or broader networks of support to cope with the intercultural living in the U.S. Indeed, meta-analyses by Yoon et al. (2011) and Gupta et al. (2013) also revealed that maintenance of heritage culture was largely unrelated to immigrants’ psychological adjustment.

Cultural Orientations, Depressive Symptoms, and Parenting

On the other hand, the results of the significant interaction between maternal American orientation and Chinese orientation in predicting depressive symptoms suggested that the acculturation-negative adjustment link in Chinese Americans is likely to be determined by the combination of the two cultural orientations rather than mothers’ orientation towards one culture (Nguyen & Benet-Martínez, 2013). We found that American cultural orientation was strongly associated with lower levels of maternal depressive symptoms when mothers maintained at least moderate levels of behavioral participation in the Chinese culture, suggesting that bicultural or integrated mothers experienced fewer depressive symptoms than those who participated in their Chinese culture but not in the larger mainstream American context.

These results, together with the conditional indirect effects described earlier, confirmed the beneficial effects of moderate to high levels of participation in both cultures for Chinese immigrant mothers with regard to lower levels of maternal depressive symptoms, and in turn, the use of lower levels of authoritarian parenting (Shin, Doh, Hong, & Kim, 2012). Previous research has found that the integration and separation acculturation styles are the most frequently used acculturation strategies across different immigrant samples (Berry & Sabatier, 2011). Integrated mothers may have a unique grasp on the complexity and nuances of the larger American culture that surrounds them despite their minority status so that they can more successfully adjust to life in the U.S. (Benet-Martínez, Lee, & Leu, 2006) than separated mothers. They may also experience less acculturative stress (Oh et al., 2002) and be able to draw resources from both Chinese and American cultures and have larger social support networks that can buffer them from psychological maladjustment (e.g., negative moods, loneliness). In contrast, separated mothers may only be able to obtain support from the relatively smaller and more dispersed Chinese community in Maryland (Tahseen & Cheah, 2012), and suffer from rejection or acculturative stress that exacerbates their depressive symptoms (Hwang & Ting, 2008). However, due to the cross-sectional design, we cannot rule out the possibility that mothers’ poorer psychological well-being may preclude their engagement in the larger mainstream culture, which may require additional psychological resources.

Positive Psychological Well-Being versus Depressive Symptoms

For the acculturation-adjustment link, the interaction between Chinese orientation and American orientation was only observed for depressive symptoms but not for positive psychological well-being. In contrast, for the adjustment-parenting link, positive psychological well-being was associated with both authoritative and authoritarian parenting styles whereas depressive symptoms were only linked to the authoritarian parenting style. This divergence may stem from the conceptual distinctiveness of the two constructs, although they can be considered the negative and positive aspects of psychological adjustment. Positive psychological well-being represents the presence of positive psychological functioning or attributes (e.g., self-acceptance, having a purpose in life, and personal growth), which is not necessarily the opposite of depression, i.e., the absence of mental illness (e.g., Keyes, 2002; Ryff & Singer, 1996). A separation acculturation strategy may lead to negative moods in these first-generation immigrant parents but may not undermine their feelings of self-acceptance and having a purpose in life. These parents might have been either in the process of adapting to the American culture (e.g., improving their English language skills) or had developed a coping system with the co-ethnic network to maintain their positive view of self and sense of mastery and efficacy in the new context despite fluctuations in mood.

In turn, the positive mastery experiences in their own life may build immigrant mothers’ feelings of confidence in their ability to effectively parent in a new cultural context (Costigan & Koryzma, 2011) by providing more warmth, reasoning-based and autonomy promoting parenting, and less reactive and coercive authoritarian parenting, both of which require more parenting resources and are considered more adaptive in the U.S. context. With depressive symptoms, on the other hand, parents might be more prone to using hostile and harsh parenting because they themselves were feeling sad, irritable, tired, etc., but negative mood may not necessarily affect use of reasoning, responsiveness, or granting autonomy. The findings are consistent with previous studies that suggest the potentially different relations of positive versus negative psychological functioning with acculturation and parenting (e.g., Meyers & Battistoni, 2003; Yoon et al., 2013).

Limitations and Future Directions

Several limitations of the present study need to be noted. First, we used cross-sectional data that precluded our ability to make causal inferences regarding the proposed relations. Therefore, the results are more in the arena of hypothesis development and exploration rather than testing definitive hypothesis and confirming a causal model. It is possible that mothers’ positive mental health leads to greater participation in both the mainstream culture and the heritage culture; Mothers’ poorer mental health may lead them to avoid participation in both cultures or to the maintenance of their heritage culture only due to the lack of psychological resources needed to learn about and adapt to the new culture (Diwan, 2008). Carefully designed longitudinal studies will be needed in future research to test the proposed causal structure in this study and to further explore the bidirectional associations between parental acculturation and psychological adjustment in Chinese and other immigrant parents.

Second, we depended on mothers’ self-report, which may reflect the mothers’ perceptions rather than their actual behavior. The use of single reporter may also increase bias in measurements. Future studies can consider spousal reports (e.g., D. Nelson et al., 2006; Porter et al., 2005) and observational assessments of parenting. Moreover, given that there are potential differences in immigrant mothers’ and fathers’ acculturation levels and in the associations between acculturation and psychological adjustment or parenting among mothers versus fathers (Chuang & Su, 2009; Costigan & Dokis, 2006; Costigan & Koryzma, 2011), future studies should sample both mothers and fathers if possible to better understand the acculturation, adjustment and parenting of both parents. Third, we examined the overall parenting styles instead of domain-specific parenting or indigenous Chinese parenting. Future studies can simultaneously examine both general and domain-specific parenting practices especially in family invention studies to obtain most optimal intervention effect (Gerards et al., 2011). Fourth, we did not collect information on neighborhood or community characteristics such as ethnic density to test the influence of context in the associations between acculturation and parenting or adjustment (Birman, 1998; Schnittker, 2002). According to segmented assimilation theory (Zhou, 1997), acculturation may lead to both positive and negative outcomes, depending on the context to which one adapts. The moderating role of contextual factors in the acculturation process should be further investigated as another way to reconcile the inconsistent findings on the implications of acculturation in the literature.

Finally, we focused only on behavioral acculturation, which measures individuals’ participation in the external aspects of American and Chinese cultures and has been shown to be different from psychological acculturation. Future examination of psychological acculturation, which reflects individuals’ identification with values, norms, beliefs, and attitudes of the two cultures (Berry, 1992; Birman & Tran, 2008) and its relations to parents’ psychological adjustment and parenting behaviors are warranted. It will be also crucial to consider both behavioral and psychological acculturation when creating acculturation profiles such that both classic and newly identified acculturation strategies may be better represented and their associations with immigrants’ psychological adjustment and parenting can be better delineated (Chia & Costigan, 2006; Tahseen & Cheah, 2012).

Summary and Implications

The results from the present study suggest acculturation as a distal contextual factor and psychological adjustment as one critical mechanism that transmits the effects of acculturation to parenting (Belsky, 1984; Costigan & Koryzma, 2011). The findings highlight the value of using a bilinear assessment of acculturation (Berry, 2003). By examining both cultural orientations and their interaction, we found immigrant mothers who experienced challenges in getting involved in the mainstream cultural context were especially at risk for decreased levels of positive psychological well-being and increasing levels of depressive symptoms. Moreover, mothers with moderate to high levels of participation in both cultures may selectively endorse adaptive behaviors from the American culture and retain valued features of the Chinese culture (Berry, 2005), leading to the most positive psychological adjustment. These findings indicate the importance of promoting immigrant parents’ ability and comfort in the new culture (e.g., enhancing their English proficiency), independently or in conjunction with promoting biculturalism (Costigan & Koryzma, 2011) through policy support and intervention efforts.

Our findings also suggest that it may be beneficial to have national, state, or community levels of programs in place to encourage immigrants’ participation with the larger society and intergroup interactions to increase parents’ confidence in navigating the mainstream and heritage cultures and in successfully parenting their children in the new cultural context. Interestingly, we found that maternal psychological well-being was more predictive of both authoritative and authoritarian parenting, but depressive symptoms were associated with only authoritarian parenting. Thus, the promotion of positive well-being, in addition to attempts to decrease negative psychological symptoms through mental health services, may have additional benefits for immigrant mothers and their children, and thus deserves further attention.

Acknowledgments

This research was conducted at the Department of Psychology, University of Maryland, Baltimore County, and was supported by National Institute of Child Health, 1R03HD052827-01 awarded to Charissa S. L. Cheah.

References

- Abbott MW, Wong S, Giles LC, Wong S, Young W, Au M. Depression in older Chinese migrants to Auckland. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;37(4):445–451. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2003.01212.x. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1614.2003.01212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D. Child care practices anteceding three patterns of preschool behavior. Genetic Psychology Monographs. 1967;75(1):43–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumrind D, Larzelere RE, Owens EB. Effects of preschool parents' power assertive patterns and practices on adolescent development. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2010;10(3):157–201. doi:10.1080/15295190903290790. [Google Scholar]

- Baydar N, Reid MJ, Webster-Stratton C. The role of mental health factors and program engagement in the effectiveness of a preventive parenting program for head start mothers. Child Development. 2003;74(5):1433–1453. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00616. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck depression inventory-II. San Antonio: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J. The determinants of parenting: A process model. Child Development. 1984;55:83–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1984.tb00275.x. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/1129836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benet-Martínez V, Lee F, Leu J. Biculturalism and cognitive complexity expertise in cultural representations. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2006;37(4):386–407. doi:10.1177/0022022106288476. [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW. Acculturation and adaptation in a new society. International Migration Quarterly Review. 1992;30:69–87. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2435.1992.tb00776.x. [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW. Immigration, acculturation and adaptation. Applied Psychology. 1997;46:5–68. doi:10.1111/j.1464-0597.1997.tb01087.x. [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW. Acculturation: Advances in theory, measurement, and applied research. In: Chun KM, Balls Organista P, Gerardo M, editors. Conceptual approaches to acculturation. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC, US: 2003. pp. 17–37. doi:10.1037/10472-004. [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW. Acculturation: Living successfully in two cultures. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 2005;29(6):697–712. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2005.07.013. [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW. A critique of critical acculturation. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 2009;33(5):361–371. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2009.06.003. [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW, Phinney JS, Sam DL, Vedder P. Immigrant youth: Acculturation, identity, and adaptation. Applied Psychology. 2006;55(3):303–332. doi:10.1111/j.1464-0597.2006.00256.x. [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW, Sabatier C. Variations in the assessment of acculturation attitudes: Their relationships with psychological wellbeing. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 2011;35(5):658–669. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2011.02.002. [Google Scholar]

- Birman D. Biculturalism and perceived competence of Latino immigrant adolescents. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1998;26(3):335–354. doi: 10.1023/a:1022101219563. doi:10.1023/A:1022101219563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birman D, Taylor-Ritzler T. Acculturation and psychological distress among adolescent immigrants from the former Soviet Union: Exploring the mediating effect of family relationships. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2007;13(4):337–346. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.4.337. doi:10.1037/1099-9809.13.4.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birman D, Tran N. Psychological distress and adjustment of Vietnamese refugees in the United States: Association with pre-and postmigration factors. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2008;78(1):109–120. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.78.1.109. doi:10.1037/0002-9432.78.1.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA. Structural equations with latent variables. Wiley; New York: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Bor W, Sanders MR. Correlates of self-reported coercive parenting of preschool-aged children at high risk for the development of conduct problems. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;38:738–745. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2004.01452.x. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1614.2004.01452.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Cote LR. Mothers’ parenting cognitions in cultures of origin, acculturating cultures, and cultures of destination. Child Development. 2004;75(1):221–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00665.x. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00665.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Hahn C, Suwalsky JT, Haynes OM. Socioeconomic status, parenting and child development: The Hollingshead four-factor index of social status and the socioeconomic index of occupations. In: Borenstein MH, Bradley R, editors. Socioeconomic status, parenting and child development. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2003. pp. 29–82. [Google Scholar]

- Chan DW. The Beck depression inventory: what difference does the Chinese version make?. Psychological Assessment: A Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;3(4):616–622. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.3.4.616. [Google Scholar]

- Chang L, Schwartz D, Dodge KA, McBride-Chang C. Harsh parenting in relation to child emotion regulation and aggression. Journal of Family Psychology. 2003;17(4):598–606. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.17.4.598. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.17.4.598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang H, Olson SL, Sameroff AJ, Sexton HR. Child effortful control as a mediator of parenting practices on externalizing behavior: Evidence for a sex differentiated pathway across the transition from preschool to school. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2011;39(1):71–81. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9437-7. doi:10.1007/s10802-010-9437-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao RK. Beyond parental control and authoritarian parenting style: Understanding Chinese parenting through the cultural notion of training. Child Development. 1994;65(4):1111–1119. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00806.x. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00806.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao R, Tseng V. Parenting of Asians. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of parenting: Social conditions and applied parenting. 2nd ed. Vol. 4. Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2002. pp. 59–93. [Google Scholar]

- Cheah CSL, Leung CYY, Tahseen M, Schultz D. Authoritative parenting among immigrant Chinese mothers of preschoolers. Journal of Family Psychology. 2009;23(3):311–320. doi: 10.1037/a0015076. doi:10.1037/a0015076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheah CSL, Leung CYY, Zhou N. Understanding “tiger parenting” through the perceptions of Chinese immigrant mothers: Can Chinese and U.S. parenting coexist? Asian American Journal of Psychology. 2013;4(1):30–40. doi: 10.1037/a0031217. doi:10.1037/a0031217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen SH, Main A, Zhou Q, Bunge SA, Lau N, Chu K. Effortful control and early academic achievement of Chinese American children in immigrant families. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 2015;30:45–56. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2014.08.004. [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Dong Q, Zhou H. Authoritative and authoritarian parenting practices and social and school performance in Chinese children. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 1997;21(4):855–873. doi:10.1080/016502597384703. [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Lee B. The Cultural and Social Acculturation Scale (Child and Adult Version) Department of Psychology, University of Western Ontario; London, Ontario, Canada: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Chia AL, Costigan CL. A person-centred approach to identifying acculturation groups among Chinese Canadians. International Journal of Psychology. 2006;41(5):397–412. doi:10.1080/00207590500412227. [Google Scholar]

- Chuang SS. Taiwanese–Canadian mothers’ beliefs about personal freedom for their young children. Social Development. 2006;15(3):520–536. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9507.2006.00354.x. [Google Scholar]

- Chuang SS, Su Y. Do we see eye to eye? Chinese mothers’ and fathers’ parenting beliefs and values for toddlers in Canada and China. Journal of Family Psychology. 2009;23(3):331–341. doi: 10.1037/a0016015. doi:10.1037/a0016015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coatsworth JD, Maldonado-Molina M, Pantin H, Szapocznik J. A person-centered and ecological investigation of acculturation strategies in Hispanic immigrant youth. Journal of Community Psychology. 2005;33(2):157–174. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20046. doi:10.1002/jcop.20046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costigan CL, Dokis DP. Similarities and differences in acculturation among mothers, fathers, and children in immigrant Chinese families. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2006;37(6):723–741. doi:10.1177/0022022106292080. [Google Scholar]

- Costigan CL, Koryzma CM. Acculturation and adjustment among immigrant Chinese parents: Mediating role of parenting efficacy. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2011;58(2):183–196. doi: 10.1037/a0021696. doi:10.1037/a0021696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costigan C, Su T. Orthogonal versus linear models of acculturation among immigrant Chinese Canadians: A comparison of mothers, fathers, and children. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2004;28(6):518–527. doi:10.1080/01650250444000234. [Google Scholar]

- Darling N, Steinberg L. Parenting style as context: An integrative model. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;113(3):487–496. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.113.3.487. [Google Scholar]

- Der-Kambetian A, Ruiz Y. Affective bicultural and global-human identity scales for Mexican-American adolescents. Psychological Reports. 1997;80(3):1027–1039. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1997.80.3.1027. doi:10.2466/pr0.1997.80.3.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diwan S. Limited English proficiency, social network characteristics, and depressive symptoms among older immigrants. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2008;63(3):S184–S191. doi: 10.1093/geronb/63.3.s184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK. Dealing with missing data in developmental research. Child Development Perspectives. 2013;7(1):27–31. doi:10.1111/cdep.12008. [Google Scholar]

- Eyou ML, Adair V, Dixon R. Cultural identity and psychological adjustment of adolescent Chinese immigrants in New Zealand. Journal of Adolescence. 2000;23(5):531–543. doi: 10.1006/jado.2000.0341. doi:10.1006/jado.2000.0341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farver JAM, Lee-Shin Y. Acculturation and Korean-American children's social and play behavior. Social Development. 2000;9(3):316–336. doi:10.1111/1467-9507.00128. [Google Scholar]

- Fritz MS, MacKinnon DP. Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychological Science. 2007;18(3):233–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01882.x. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01882.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerards SM, Sleddens EF, Dagnelie PC, VRIES NK, Kremers SP. Interventions addressing general parenting to prevent or treat childhood obesity. International Journal of Pediatric Obesity. 2011;6(2Part2):e28–e45. doi: 10.3109/17477166.2011.575147. doi:10.3109/17477166.2011.575147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield PM, Keller H, Fuligni A, Maynard A. Cultural pathways through universal development. Annual Review of Psychology. 2003;54(1):461–490. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145221. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta A, Leong F, Valentine JC, Canada DD. A meta-analytic study: The relationship between acculturation and depression among Asian Americans. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2013;83(2-3):372–385. doi: 10.1111/ajop.12018. doi:10.1111/ajop.12018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutman LM, Friedel JN, Hitt R. Keeping adolescents safe from harm: Management strategies of African-American families in a high-risk community. Journal of School Psychology. 2003;41(3):167–184. doi:10.1016/S0022-4405(03)00043-8. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs. 2009;76(4):408–420. doi:10.1080/03637750903310360. [Google Scholar]

- Ho GW. Acculturation and its implications on parenting for Chinese immigrants A systematic review. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2014;25(2):145–158. doi: 10.1177/1043659613515720. doi:10.1177/1043659613515720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AA. Four-factor index of social status. Yale University; New Haven, CT.: 1975. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to under parameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods. 1998;3(4):424. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.3.4.424. [Google Scholar]

- Huppert FA, Whittington JE. Evidence for the independence of positive and negative well-being: Implications for quality of life assessment. British Journal of Health Psychology. 2003;8(1):107–122. doi: 10.1348/135910703762879246. doi:10.1348/135910703762879246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang WC, Ting JY. Disaggregating the effects of acculturation and acculturative stress on the mental health of Asian Americans. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2008;14(2):147–154. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.14.2.147. doi:10.1037/1099-9809.14.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwamoto DK, Liu WM. The impact of racial identity, ethnic identity, Asian values, and race-related stress on Asian Americans and Asian international college students’ psychological well-being. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2010;57(1):79–91. doi: 10.1037/a0017393. doi:10.1037/a0017393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes CL. The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2002;43(2):207–222. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3090197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes CL, Dhingra SS, Simoes EJ. Change in level of positive mental health as a predictor of future risk of mental illness. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(12):2366–2371. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.192245. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2010.192245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HS, Sherman DK. “Express yourself”: culture and the effect of self-expression on choice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;92(1):1–11. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.1.1. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.92.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SY, Shen Y, Huang X, Wang Y, Orozco-Lapray D. Chinese American parents’ acculturation and enculturation, bicultural management difficulty, depressive symptoms, and parenting. Asian American Journal of Psychology. 2014;5(4):298–306. doi: 10.1037/a0035929. doi: 10.1037/a0035929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau AS. Physical discipline in Chinese American immigrant families: An adaptive culture perspective. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2010;16(3):313–322. doi: 10.1037/a0018667. doi:10.1037/a0018667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee EH, Zhou Q, Ly J, Main A, Tao A, Chen SH. Neighborhood characteristics, parenting styles, and children's behavioral problems in Chinese American immigrant families. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2014;20(2):202–212. doi: 10.1037/a0034390. doi:10.1037/a0034390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CYC, u, V. R. A comparison of child-rearing practices among Chinese, immigrant Chinese, and Caucasian-American parents. Child Development. 1990;61(2):429–433. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02789.x. [Google Scholar]

- Liu LL, Lau AS, Chen ACC, Dinh KT, Kim SY. The influence of maternal acculturation, neighborhood disadvantage, and parenting on Chinese American adolescents’ conduct problems: Testing the segmented assimilation hypothesis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38(5):691–702. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9275-x. doi:10.1007/s10964-008-9275-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little TD. Longitudinal Structural Equation Modeling. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Loehlin JC. Latent variable models: An introduction to factor, path, and structural analysis. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Lovejoy MC, Graczyk PA, O'Hare E, Neuman G. Maternal depression and parenting behavior: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2000;20(5):561–592. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(98)00100-7. doi:10.1016/S0272-7358(98)00100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Krull JL, Lockwood CM. Equivalence of the mediation, confounding and suppression effect. Prevention Science. 2000;1(4):173–181. doi: 10.1023/a:1026595011371. doi:10.1023/A:1026595011371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers SA, Battistoni J. Proximal and distal correlates of adolescent mothers' parenting attitudes. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2003;24(1):33–49. doi:10.1016/S0193-3973(03)00023-6. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B, Asparouhov T. Latent variable analysis with categorical outcomes: Multiple-group and growth modeling in Mplus. Mplus web notes. 2002;4(5):1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User's Guide. Seventh Edition Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 1998-2012. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson DA, Hart CH, Yang C, Olsen JA, Jin S. Aversive parenting in China: Associations with child physical and relational aggression. Child Development. 2006;77(3):554–572. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00890.x. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen A-MD, Benet-Martínez V. Biculturalism and adjustment: A meta-analysis. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2013;44:122–159. doi:10.1177/0022022111435097. [Google Scholar]

- Oh Y, Koeske GF, Sales E. Acculturation, stress, and depressive symptoms among Korean immigrants in the United States. The Journal of Social Psychology. 2002;142(4):511–526. doi: 10.1080/00224540209603915. doi:10.1080/00224540209603915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter CL, Hart CH, Yang C, Robinson CC, Olsen SF, Zeng Q, Jin S. A comparative study of child temperament and parenting in Beijing, China and the western United States. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2005;29(6):541–551. doi:10.1177/01650250500147402. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. The Sage sourcebook of advanced data analysis methods for communication research. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2008. Assessing mediation in communication research. pp. 13–54. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Rucker DD, Hayes AF. Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2007;42(1):185–227. doi: 10.1080/00273170701341316. doi:10.1080/00273170701341316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryder AG, Alden LE, Paulhus DL. Is acculturation unidimensional or bidimensional? A head-to-head comparison in the prediction of personality, self-identity, and adjustment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79(1):49–65. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.1.49. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.79.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD, Keyes CLM. The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:719–727. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.4.719. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.69.4.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD, Singer B. Psychological well-being: Meaning, measurement, and implications for psychotherapy research. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 1996;65(1):14–23. doi: 10.1159/000289026. doi:10.1159/000289026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnittker J. Acculturation in context: The self-esteem of Chinese immigrants. Social Psychology Quarterly. 2002;65(1):56–76. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3090168. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Zamboanga BL, Szapocznik J. Rethinking the concept of acculturation: implications for theory and research. American Psychologist. 2010;65(4):237–251. doi: 10.1037/a0019330. doi:10.1037/a0019330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin JH, Doh HS, Hong JS, Kim JS. Pathways from non-Korean mothers' cultural adaptation, marital conflict, and parenting behavior to bi-ethnic children's school adjustment in South Korea. Children and Youth Services Review. 2012;34(5):914–923. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.01.018. [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and non-experimental studies: new procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods. 2002;7(4):422–445. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.7.4.422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME. Some new results on indirect effects and their standard errors in covariance structure models. Sociological Methodology. 1986;16:159–186. [Google Scholar]

- Sorkhabi N. Applicability of Baumrind's parent typology to collective cultures: Analysis of cultural explanations of parent socialization effects. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2005;29(6):552–563. doi: 10.1177/01650250500172640. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens J. Applied multivariate statistics for the social sciences. Lawrence-Eribaum; Mahwah, NJ: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Tahseen M, Cheah CSL. A multidimensional examination of the acculturation and psychological functioning of a sample of immigrant Chinese mothers in the US. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2012;36(6):430–439. doi: 10.1177/0165025412448605. doi:10.1177/0165025412448605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi R, Yun S, Russell JE. Antecedents and consequences of the perceived adjustment of Japanese expatriates in the USA. International Journal of Human Resource Management. 2002;13(8):1224–1244. doi:10.1080/09585190210149493. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai JL, Chentsova-Dutton Y. Models of cultural orientation: Differences between American-born and overseas-born Asians. In: Kurasaki K, Okazaki S, Sue S, editors. Asian American mental health: Assessment theories and methods. 2002. pp. 95–106. [Google Scholar]

- Turney K. Labored love: Examining the link between maternal depression and parenting behaviors. Social Science Research. 2011;40(1):399–415. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2010.09.009. [Google Scholar]

- White R, Roosa MW, Weaver SR, Nair RL. Cultural and contextual influences on parenting in Mexican American families. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2009;71(1):61–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00580.x. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00580.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson S, Durbin CE. Effects of paternal depression on fathers' parenting behaviors: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30(2):167–180. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.10.007. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winzer R, Lindblad F, Sorjonen K, Lindberg L. Positive versus negative mental health in emerging adulthood: a national cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):1238–1245. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1238. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-14-1238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong YJ, Tran KK, Kim SH, Van Horn Kerne V, Calfa NA. Asian Americans' lay beliefs about depression and professional help seeking. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2010;66(3):317–332. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20653. Doi:10.1002/jclp.20653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu DY. Parental control: Psychocultural interpretations of Chinese patterns of socialization. In: Lau S, editor. Growing up the Chinese way: Chinese child and adolescent development. The Chinese University Press; Hong Kong: 1996. pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Wu P, Robinson CC, Yang C, Hart CH, Olsen SF, Porter CL, Jin S, Wo J, Wu X. Similarities and differences in mothers’ parenting of preschoolers in China and the United States. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2002;26(6):481–491. doi:10.1080/01650250143000436. [Google Scholar]

- Ying YW, Lee PA, Tsai JL. Cultural orientation and racial discrimination: Predictors of coherence in Chinese American young adults. Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;28(4):427–441. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon E, Chang CT, Kim S, Clawson A, Cleary SE, Hansen M, Gomes AM. A meta-analysis of acculturation/enculturation and mental health. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2013;60(1):15–30. doi: 10.1037/a0030652. doi:10.1037/a0030652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon E, Langrehr K, Ong LZ. Content analysis of acculturation research in counseling and counseling psychology: A 22-year review. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2011;58(1):83–96. doi: 10.1037/a0021128. doi:10.1037/a0021128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu W, Cheah CSL, Sun S. The moderating role of English proficiency in the association between immigrant Chinese mothers’ authoritative parenting and children's outcomes. The Journal of Genetic Psychology: Research and Theory on Human Development. 2015;176(4):272–279. doi: 10.1080/00221325.2015.1022503. DOI: 10.1080/00221325.2015.1022503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan KH, Bentler PM. Three likelihood-based methods for mean and covariance structure analysis with nonnormal missing data. Sociological Methodology. 2000;30(1):165–200. Doi:10.1111/0081-1750.00078. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M. Segmented assimilation: Issues, controversies, and recent research on the new second generation. International Migration Review. 1997;31(4):975–1008. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2547421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]