Abstract

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small endogenous non-coding RNAs of about 22 nt in length that take crucial roles in many biological processes. These short RNAs regulate the expression of mRNAs by binding to their 3′-UTRs or by translational repression. Many of the current studies focus on how mature miRNAs regulate mRNAs, however, very limited knowledge is available regarding their transcriptional loci. It is known that primary miRNAs (pri-miRs) are first transcribed from the DNA, followed by the formation of precursor miRNAs (pre-miRs) by endonuclease activity, which finally produces the mature miRNAs. Till date, many of the pre-miRs and mature miRNAs have been experimentally verified. But unfortunately, identification of the loci of pri-miRs, promoters and associated transcription start sites (TSSs) are still in progress. TSSs of only about 40% of the known mature miRNAs in human have been reported. This information, albeit limited, may be useful for further study of the regulation of miRNAs. In this paper, we provide a novel database of validated miRNA TSSs, miRT, by collecting data from several experimental studies that validate miRNA TSSs and are available for full download. We present miRT as a web server and it is also possible to convert the TSS loci between different genome built. miRT might be a valuable resource for advanced research on miRNA regulation, which is freely accessible at: http://www.isical.ac.in/~bioinfo_miu/miRT/miRT.php.

Keywords: MicroRNA, Transcription start site, Primary transcript, Transcriptional regulation, Database

Introduction

Current research interests in molecular biology are largely focused on various types of short and long non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) [1]. Of the various subclasses of ncRNAs, microRNAs (miRNAs) are the most thoroughly characterized subclass of short RNAs in the recent literature [2]. MiRNAs are short (∼22 nt) and single stranded endogenous RNA molecules. They regulate mRNAs by binding to the 3′-UTRs of their target mRNAs or by translational repression [3], [4]. Through the negative regulatory mechanism at the posttranscriptional level, miRNAs get involved in controlling diverse biological processes like cellular proliferation and differentiation [5]. This is the reason why they are important in therapeutic approaches to carcinogenesis and many other diseases.

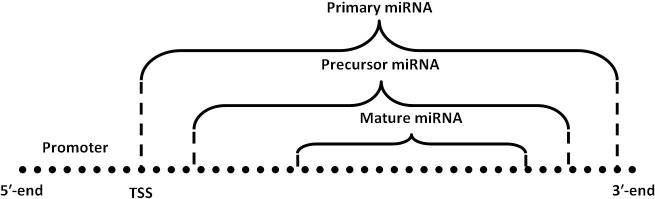

The biogenesis of miRNAs is initiated with the generation of primary miRNAs (pri-miRs), which are expressed as a longer part of the transcript, out of the DNA [6]. The nuclear RNase III enzyme Drosha cleaves this longer transcript to produce the stem-loop precursor miRNA (pre-miR), an intermediate of length 70–110 nt [6], [7], [8], [9]. Pre-miRNAs, which form short RNA hairpins containing a 2-nt 3′ overhang [10], are then bound by the nuclear export factor exportin 5 to be transported to the cytoplasm [11], [12]. At this stage, another RNase III enzyme termed Dicer removes the terminal loop of the pre-miR to generate a ∼22 bp miRNA duplex with 2-nt 3′ overhangs [6]. One strand of this short-lived duplex degrades due to poor thermodynamic stability while the other strand, the one with less stable 5′-antisense terminal base pair, remains as the mature miRNA [13], [14]. The transcriptional loci of a mature miRNA and its primary and precursor transcripts are shown in Figure 1. The mature miRNA is finally incorporated into a multi-protein complex, termed as RNA induced silencing complex (RISC). The incorporated strand (also known as the guide strand) is selected by the argonaute protein and the remaining strand (also called the passenger strand) is degraded as a RISC complex substrate. The guide strand functions to drive RISC to the complementary mRNA targets [15], [16], [17]. When RISC finds the complementary mRNA, it activates RNase to cleave and hence controls its biological activities.

Figure 1.

Loci of TSS and different forms of miRNA Each mature miRNA can be mapped back to a contiguous stretch on a single DNA strand spanned by the pre-miR and further by the pri-miR whose upstream region is marked as the promoter. The exact locus of TSS is required to identify the promoter.

Although sufficient experimental knowledge about the biogenesis of miRNA has already been gathered (and also about pre- and mature miRNAs), enough information about the TSSs of pri-miRs is not yet available. This is the reason why prediction of TSSs is an emerging area of research [18]. The knowledge about pri-miR TSSs should help us to understand the transcriptional regulation of miRNA and thus its biological activity in depth. This will also help to provide accurate information about the promoter region of miRNAs.

Based on the genomic locus, miRNAs can be broadly categorized into two types — intragenic (miRNA-coding genes located within their host protein-coding genes) and intergenic (miRNA-coding genes located in-between protein-coding genes) [7]. It is highly anticipated that most of the intergenic miRNAs (inter-miRs) are transcribed independently with their own RNA polymerase II (Pol II) promoters, while intragenic miRNAs (intra-miRs) are transcribed along with their host genes [3]. However, recent reports indicate that intra-miRs have their own unique promoters, and interestingly, some intronic miRNAs are also found to have their own promoters [19]. There are recent attempts to understand the transcriptional regulation of inter-miRs [3], [4], [19], as very little is known about whether their transcription is associated with that of their neighbouring genes at all. In fact, the nature of the primary transcripts of inter-miRs is still not fully explored [3]. The localization of transcription start sites (TSSs) in the upstream region of the precursor miRNAs (pre-miR) that are intergenic is thus an important object of study.

Only a few pri-miR sequences have been recognized experimentally a decade earlier [20], [21], [22], [23]. Landgraf et al. are the first to infer a large set of pri-miRs, along with pre-miRs and mature miRNAs, by analyzing the expression of over 250 small RNAs (based on cDNA libraries) through cloning and sequencing [24]. The examined miRNAs reflect some additional properties like precise 5′-end processing, asymmetric strand accumulation, and sequence conservation. Small RNA libraries are sequenced from 26 different organs and cell types of human and mouse and used for the identification of the complete transcripts to report the TSS regions along with chromosomal location and strand of about 200 human miRNAs.

Very recently, several attempts have been made to characterize the promoters of human inter-miRs at the genome-wide level [3], [4], [19]. Zhou et al. have investigated transcriptional regulations in human along with Caenorhabditis elegans, Arabidopsis thaliana and Oryza sativa [4]. They have found that promoters of most of the known miRNA genes are similar to those of the protein-coding genes. However, TATA-boxes do not appear to be compulsory for most of the human miRNA genes identified. Their study reveals some motifs that are specific to miRNA genes in individual species, some of which are conserved across different species.

To better understand the structure of primary transcript of inter-miRs, Saini et al. have analyzed the TSSs, CpG islands, polyadenylation signals, EST data, transcription factor binding sites (TFBSs) and expression ditag data surrounding inter-miRs in the human genome [3]. They notice that a significant portion of the primary transcripts of inter-miRs are 3–4 kb long, with clearly-defined 5′ and 3′ boundaries. They have reported the complete transcript structure of a couple of human miRNAs and predicted the TSSs of about 200 miRNAs using Eponine.

Oszolak et al. have predicted the location of the proximal promoters of 175 human miRNAs by combining nucleosome mapping with promoter chromatin signatures in three cancer cell lines [25]. Out of these, one-third of the intronic miRNAs have transcription initiation regions independent from their host promoters. Of the miRNAs studied, 87 are intergenic with novel promoters, 88 miRNA genes are intronic with 32 containing clearly identifiable promoters distinct from those of their hosts. They finally derive a single locus as TSSs of miRNA genes from the regions initially obtained.

In another study, putative promoter regions (miPPRs) of 79 miRNAs have been validated experimentally or from previous reports [26]. Some of these miRNAs share the same miPPR, suggesting that they are generated as polycistronic transcripts. The distances between 22 miPPRs and their corresponding miRNA hairpin regions are found to be longer than 10 kb, while the median distance of the entire set is 5.5 kb. Most of these miPPRs are apart from the promoters of the overlapping genes, indicating that their expressions are regulated independently.

The ChIP-seq data has been used for the first time by Marson et al. to identify the region of promoters of miRNA genes in embryonic stem cells and quantitative sequencing of short transcripts in multiple cell types [27]. Using the start of the first miRNA of each cluster as the putative TSS, they have observed highly overlapping occupancy of Oct4, Sox2, Nanog, and Tcf3 at the TSSs of miRNA transcripts and provide information for the TSS region along with the chromosomal details for approximately 550 miRNAs.

Corcoran et al. have performed Pol II ChIP-chip using a custom array surrounding the regions of known miRNA genes from A549 lung epithelial cells with a Pol II specific antibody and show that the promoters of miRNA genes share the same general features as those of protein-coding genes [19]. They have indicated that miRNA genes can be transcribed from promoters located several kilobases away. They have prepared new familial binding profiles [28], which are employed to obtain the TSSs of the intra-miRs transcribed from their own unique promoters and even those of the intra-miRs for which the nearest ChIP-chip overlaps with the TSSs of their host genes.

In one of the very recent analyses, Chien et al. have integrated a set of experimental TSSs of human miRNAs and established a resource named as miRStart for further research based on the resources like cap analysis of gene expression (CAGE) tags, TSS Seq libraries and H3K4me3 chromatin signature derived from high-throughput sequencing analysis of gene initiation [29]. They have further investigated the putative miRNA TSSs and also verified whether miRNA TSSs are located within intergenic or intragenic regions based on an SVM model. This work has successfully identified 847 human miRNA TSSs (292 of them corresponds to 70 miRNA clusters) based on high-throughput sequencing data from TSS-relevant experiments.

Here in this paper, we report about a database that accumulates experimentally-validated TSSs of miRNAs, which we call hereafter as miRT. We collect results from the recent biological studies experimentally validating the TSSs of miRNAs, and present the entire information in the form of a web server. This will be useful for accurate identification of regulatory regions and investigation of transcriptional machinery.

Methods

As reflected by the limited earlier studies, there is scarcity of validated information about the TSSs of miRNAs and in fact this is scattered. We have tried to accumulate all the experimentally-validated details available till date as a database of TSSs for human miRNAs. How we have prepared the database and presented the entire information as a web server with some unique features is described below.

Preparation of miRT

To collect information about the miRNA TSSs, we have carried out extensive PubMed search. We accumulate the information about the TSSs of miRNAs that have been reported based on different experimental approaches. We review the various studies and sort out only the TSSs reported for human miRNAs, as per their types and loci. Due to the continuing progress of sequence-based analysis and assembly, these studies are diffuse in different genome builts. To be specific, these TSS loci are reported on the basis of separate assemblies – hg17, hg18 and hg19. Moreover, diverse biological properties have been analyzed in these experiments, which are very much inconsistent with each other. To sum up, these studies include small RNA sequencing, polyadenylation signals, CpG islands, EST data, TFBSs, expression ditag, CAGE tags, nucleosome mapping, promoter chromatin signatures, biochemical experiment, cDNA clones, ChIP-seq data, ChIP-chip data, TSS Seq and H3K4me3. All these are highlighted briefly in Table 1. Based on these studies, we accumulate the TSS loci that have been validated for miRNAs.

Table 1.

Summary of the information currently available about the TSSs of human miRNAs and biological experiments employed for identification

| No. of miRNAs | Assembly | Information analyzed | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| 204 | hg17 | Small RNA sequencing | [24] |

| 29 | hg17 | Polyadenylation signals, CpG islands, EST data, TFBSs, expression ditag, CAGE tags | [3] |

| 182 | hg18 | Nucleosome mapping, promoter chromatin signatures | [25] |

| 95 | hg17 | Biochemical experiment, cDNA clones | [26] |

| 550 | hg17 | ChIP-seq data | [27] |

| 65 | hg18 | ChIP-chip data | [19] |

| 318 | hg19 | CAGE tags, TSS Seq, H3K4me3 chromatin signature | [29] |

Details

The miRT database includes information about the TSSs with a minimum support value of one. The term support means a study that reports about a TSS locus of an miRNA and support value denotes total number of supports obtained for an miRNA. In total, 588 miRNAs (closer to 40% of the known mature miRNAs) are included in miRT. Of these, the ratio of inter- and intra-miRs is approximately 1:2. However, the number of reported TSSs is higher than the number of miRNAs because for some of them multiple TSSs have been experimentally obtained. The average support value, which means the number of references in which there is a report about the experimentally-validated TSS of a specific miRNA, of miRT is quite high, establishing the significance of the accumulated information. The statistical details about the miRNA TSSs provided through the miRT database are given in Table 2. Notably, the number of TSS loci is higher than that of miRNAs, indicating that there are multiple inputs for TSS locus information about a single miRNA.

Table 2.

The basic statistics about the miRT database

| Attribute | Value |

|---|---|

| No. of miRNAs | 588 |

| No. of inter-miRs | 206 |

| No. of intra-miRs | 382 |

| No. of TSS loci | 670 |

| Maximum support value | 7 |

| The miRNA with maximum support | hsa-let-7i |

| Average support value | 2.27 |

| Median support value | 2 |

Note: The support value denotes total number of supporting studies.

Availability

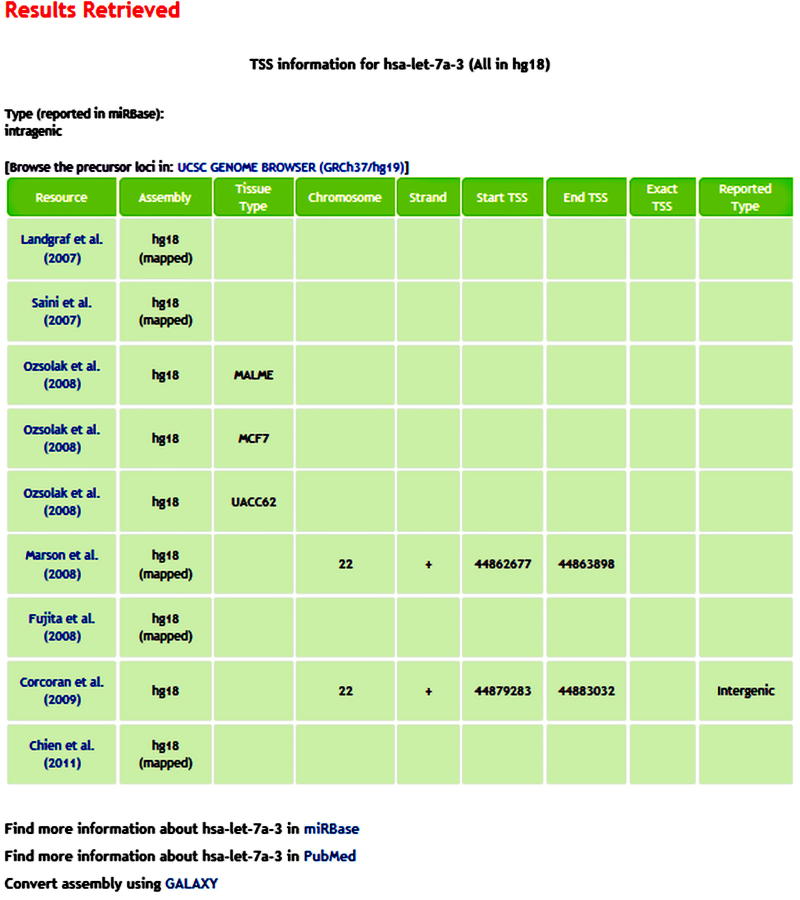

The entire miRNA TSS dataset is available through the miRT web server at: http://www.isical.ac.in/~bioinfo_miu/miRT/miRT.php. The interface is prepared in PHP. The TSS information is accessible through queries against miRNA names given as input. The entire data, in original assemblies, can also be downloaded as tab-delimited text or excel formats. This is open to all types of browsers and also linked to some useful repositories like UCSC Genome Browser and miRBase. An outlook of the output page extracted through miRT web server is shown in Figure 2. Further update of the TSS resource by request can be achieved by contacting the corresponding author.

Figure 2.

The information retrieved from miRT web server against a query The tabular representation of TSS information for hsa-let-7a-3 retrieved through the miRT web server along with some additional features. The extracted information about the TSSs of an miRNA varies by genome assemblies in different studies. They can be mapped to a common assembly through miRT.

Results

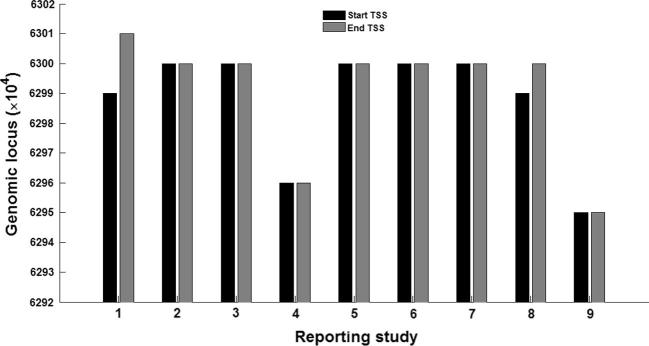

To examine the variability of the different experimental results reported in the studies reviewed in the present work, we have carried out miRNA-specific analysis by converting all the TSSs to a fixed gene assembly (hg19). We took the miRNA hsa-let-7i as an example for illustration. There are seven papers reporting about the TSS (may be a region with start TSS and end TSS or a fixed locus) of this miRNA. We convert the different experimentally validated TSSs to a common gene built (hg19). The comparative plots of the various start and end site of the TSSs, as experimentally-observed in different studies, of hsa-let-7i are shown in Figure 3. These include nine loci (three from three different cell lines in [25] and one from each of the others [3], [19], [24], [26], [27], [29]) of the same miRNA that are very close with respect to the large span of the genome, although they differ much (σ ∼ 17225.6 for start TSS and σ ∼ 19656.4 for end TSS, where the values are represented in nt and σ denotes the standard deviation).

Figure 3.

The variation between different TSSs of hsa-let-7i reported in various experiments The variation between TSSs (all mapped to hg19) experimentally obtained in different studies on miRNA hsa-let-7i is shown as a plot. The individual studies are marked along the X-axis as (1) Landgraf et al. (2) Saini et al. (3) Marson et al. (4) Fujita et al. (5) Ozsolak et al. (MALME), (6) Ozsolak et al. (MCF7), (7) Ozsolak et al. (UACC62), (8) Corcoran et al. and (9) Chien et al. The Y-axis denotes the locus on the genome.

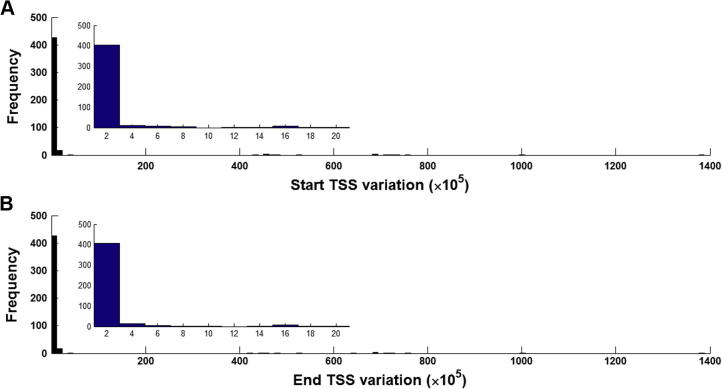

To further reflect the variation of reported TSSs globally between different experimental studies, we plot frequency distributions against the TSS variability of the entire database. As the TSSs are reported as regions by some studies, there might be varying start and end sites. We have converted all such regions from the database to current human genome assembly hg19 (please note that we can only define a variation between the reported loci of TSSs where the support value is more than one). We compute the variation as the difference between the maximum and minimum reported sites with respect to the 5′-end. Then, we plot the frequency distributions of this variability in Figure 4, showing the disparity between the reported start and end TSSs. It is noted that in spite of using a standard assembly, the reported TSSs are located more than 107 bases apart in some cases, mainly because this type of studies is noise-prone and not yet systematic and robust.

Figure 4.

The variation between different TSS regions of miRNAs included in miRT The variability between TSSs (all mapped to hg19) of the miRNAs included in miRT for which the support value is at least two is shown as a frequency distribution. The variations between the beginning of the reported TSS regions (A) and end of the reported TSS regions (B) are represented along the X-axis, and the numbers of miRNAs are represented on Y-axis. The insets in both the panels show the distributions zoomed within the range 1–20 along the X-axis.

Discussion

MicroRNAs are produced from longer transcripts which can code for more than one mature miRNAs. A recently published database, the miRGen 2.0 (http://www.microrna.gr/mirgen), aims to provide comprehensive information about the position of human and mouse miRNA coding transcripts and their regulation by TFs with properly-compiled experimental supporting data [30]. By compiling the data produced by [19], [24], [25], [27], Alexiou et al. have identified 812 human miRNA-coding transcripts and 386 mouse miRNA-coding transcripts in total. Of them, 423 are annotated as intra-miRA transcripts. It is the first attempt to build a widely-accessible database that connects TFs and miRNAs. Unfortunately, miRGen 2.0 is not specific to TSS information as per any standard assembly. It is required to make this type of information consistent between assemblies.

The miRGen 2.0 reports about the different transcripts of miRNAs from multiple species and poorly-characterized TFs of miRNAs and their main focus remains in finding putative TFs of miRNAs. On the contrary, our major focus is to accumulate the experimentally-validated and updated TSS information of human miRNAs. miRGen 2.0 does not include assembly (genome built) information as well as recent results based on the next-generation sequencing [29]. In addition, miRGen 2.0 does not provide the platform for further analyses. In particular, miRT provides extended information over miRGen 2.0, including assembly and other information for its further usability.

The main advantage of miRT is that it provides information convertible to a number of recent genome assemblies. The TSS data can be converted from its reported assembly to any other assembly, which increases the usability of the data for further analyses. In addition, miRT interface provides some utility features that are helpful for further integrative analysis. Any miRNA name given as a query item is directly linked with the genome browser of UCSC to provide various features of the region covered by its mature transcript. It also reports the genomic type and other related information about a specific miRNA from the miRBase [7]. As the accumulated information for a specific miRNA is diverse by loci and also assembly (hg17, hg18 and hg19), we have retained an option to directly link it to the GALAXY web server [31] for assembly conversion using the Lift-Over tool or for other purposes. Finally, one can obtain more information for any arbitrary miRNA from the publications available in PubMed. Thus, miRT has been made a complete platform for transcriptional regulation analysis.

Conclusion

The current paper reports the assembly of biologically-validated TSS information of a large number of (588 currently and further upgradable) human miRNAs. It integrates the entire data as a database and present in the form of a web server. This provides a significant resource for further analysis of transcriptional regulation of these short RNA regulators. There are recent attempts to predict TSSs of miRNAs for human [18]. However, these approaches suffer from insufficient supply of positive samples and could be improved with our integrated data. Further, genome-wide expression analyses of miRNAs might also benefit from accurate TSS information [32]. Global prediction of promoter regions of miRNA genes would allow exploring the underlying mechanisms of gene regulatory activities by these miRNAs. As highlighted by Zhou et al. [4], conserveness analysis may also provide additional confirmation of the TSS loci. As a whole, there are many open directions of further study.

Authors’ contributions

MB and MD carried out literature survey. MB prepared the miRT web server. MB and SB wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declared that no competing interests exist.

Acknowledgments

S. Bandyopadhyay gratefully acknowledges the financial support from the Swarnajayanti Fellowship scheme of the Department of Science and Technology, Government of India (Grant No. DST/SJF/ET-02/2006-07). The authors are grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and suggestions.

References

- 1.Li M., Marin-Muller C., Bharadwaj U., Chow K.H., Yao Q., Chen C. MicroRNAs: control and loss of control in human physiology and disease. World J Surg. 2009;33:667–684. doi: 10.1007/s00268-008-9836-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartel D.P. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136:215–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saini H.K., Griffiths-Jones S., Enright A.J. Genomic analysis of human microRNA transcripts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:17719–17724. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703890104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou X., Ruan J., Wang G., Zhang W. Characterization and identification of microRNA core promoters in four model species. PLoS Comput Biol. 2007;3:e37. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen D., Farwell M.A., Zhang B. MicroRNA as a new player in the cell cycle. J Cell Physiol. 2010;225:296–301. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee Y., Ahn C., Han J., Choi H., Kim J., Yim J. The nuclear RNase III drosha initiates microRNA processing. Nature. 2003;425:415–419. doi: 10.1038/nature01957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Griffiths-Jones S., Saini H.K., van Dongen S., Enright A.J. miRBase: tools for microRNA genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D154–D158. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee Y., Jeon K., Lee J., Kim S., Kim V.N. MicroRNA maturation: stepwise processing and subcellular localization. EMBO J. 2002;21:4663–4670. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zeng Y., Cullen B.R. Sequence requirements for microRNA processing and function in human cells. RNA. 2003;9:112–123. doi: 10.1261/rna.2780503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krol J., Sobczak K., Wilczynska U., Drath M., Jasinska A., Kaczynska D. Structural features of microRNA (miRNA) precursors and their relevance to miRNA biogenesis and small interfering RNA/short hairpin RNA design. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:42230–42239. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404931200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lund E., Güttinger S., Calado A., Dahlberg J.E., Kutay U. Nuclear export of microRNA precursors. Science. 2004;303:95–98. doi: 10.1126/science.1090599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yi R., Qin Y., Macara I.G., Cullen B.R. Exportin-5 mediates the nuclear export of pre-microRNAs and short hairpin RNAs. Genes Dev. 2003;17:3011–3016. doi: 10.1101/gad.1158803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khvorova A., Reynolds A., Jayasena S.D. Functional siRNAs and miRNAs exhibit strand bias. Cell. 2003;115:209–216. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00801-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwarz D.S., Hutvágner G., Du T., Xu Z., Aronin N., Zamore P.D. Asymmetry in the assembly of the RNAi enzyme complex. Cell. 2003;115:199–208. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00759-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hammond S.M., Bernstein E., Beach D., Hannon G.J. An RNA-directed nuclease mediates posttranscriptional gene silencing in Drosophila cells. Nature. 2000;404:293–296. doi: 10.1038/35005107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martinez J., Patkaniowska A., Urlaub H., Lührmann R., Tuschl T. Single-stranded antisense siRNAs guide target RNA cleavage in RNAi. Cell. 2002;110:563–574. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00908-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schwarz D.S., Hutvágner G., Haley B., Zamore P.D. Evidence that siRNAs function as guides, not primers, in the Drosophila and human RNAi pathways. Mol Cell. 2002;10:537–548. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00651-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhattacharyya M., Feuerbach L., Bhadra T., Lengauer T., Bandyopadhyay S. MicroRNA transcription start site prediction with multi-objective feature selection. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol. 2012;11:6. doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Corcoran D.L., Pandit K.V., Gordon B., Bhattacharjee A., Kaminski N., Benos P.V. Features of mammalian microRNA promoters emerge from polymerase II chromatin immunoprecipitation data. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e5279. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cai X., Hagedorn C.H., Cullen B.R. Human microRNAs are processed from capped, polyadenylated transcripts that can also function as mRNAs. RNA. 2004;10:1957–1966. doi: 10.1261/rna.7135204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim Y.K., Kim V.N. Processing of intronic microRNAs. EMBO J. 2007;26:775–783. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee Y., Kim M., Han J., Yeom K., Lee S., Baek S.H. MicroRNA genes are transcribed by RNA polymerase II. EMBO J. 2004;23:4051–4060. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taganov K.D., Boldin M.P., Chang K.J., Baltimore D. NF-kappaB-dependent induction of microRNA miR-146, an inhibitor targeted to signaling proteins of innate immune responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:12481–12486. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605298103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Landgraf P., Rusu M., Sheridan R., Sewer A., Iovino N., Aravin A. A mammalian microRNA expression atlas based on small RNA library sequencing. Cell. 2007;129:1401–1414. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.04.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ozsolak F., Poling L.L., Wang Z., Liu H., Liu X.S., Roeder R.G. Chromatin structure analyses identify miRNA promoters. Genes Dev. 2008;22:3172–3183. doi: 10.1101/gad.1706508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fujita S., Iba H. Putative promoter regions of miRNA genes involved in evolutionary conserved regulatory systems among vertebrates. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:303–308. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marson A., Levine S.S., Cole M.F., Frampton G.M., Brambrink T., Johnstone S. Connecting microRNA genes to the core transcriptional regulatory circuitry of embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2008;134:521–533. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mahony S., Auron P.E., Benos P.V. DNA familial binding profiles made easy: comparison of various motif alignment and clustering strategies. PLoS Comput Biol. 2007;3:e61. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chien C., Sun Y., Chang W., Chiang-Hsieh P., Lee T., Tsai W. Identifying transcriptional start sites of human microRNAs based on high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:9345–9356. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alexiou P., Vergoulis T., Gleditzsch M., Prekas G., Dalamagas T., Megraw M. MiRGen 2.0: a database of microRNA genomic information and regulation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D137–D141. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blankenberg D., Kuster G.V., Coraor N., Ananda G., Lazarus R., Mangan M. Galaxy: a web based genome analysis tool for experimentalists. Curr Protoc Mol Biol. 2010;19:1–21. doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb1910s89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stählera C.F., Kellera A., Leidingerb P., Backesb C., Chandranc A., Wischhusenc J. Whole miRNome wide differential co-expression of microRNAs. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2012;10:285–294. doi: 10.1016/j.gpb.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]