Abstract

Nearly two decades have passed since the publication of the first study reporting the discovery of microRNAs (miRNAs). The key role of miRNAs in post-transcriptional gene regulation led to the performance of an increasing number of studies focusing on origins, mechanisms of action and functionality of miRNAs. In order to associate each miRNA to a specific functionality it is essential to unveil the rules that govern miRNA action. Despite the fact that there has been significant improvement exposing structural characteristics of the miRNA–mRNA interaction, the entire physical mechanism is not yet fully understood. In this respect, the development of computational algorithms for miRNA target prediction becomes increasingly important. This manuscript summarizes the research done on miRNA target prediction. It describes the experimental data currently available and used in the field and presents three lines of computational approaches for target prediction. Finally, the authors put forward a number of considerations regarding current challenges and future directions.

Keywords: MicroRNAs, MicroRNA recognition elements, Target prediction

Introduction

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are short endogenous non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), central actors in post-transcriptional regulation [1]. miRNAs bind the protein complex called RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) and guide the complex toward specific sites, in particular mRNAs known as genes targets. By pairing specific sites in the mRNAs known as miRNA recognition elements (mRE), miRNAs direct post-transcriptional regulation, resulting in mRNA degradation or inhibition of protein translation.

However, the rules governing the mechanism of miRNA target regulation are not yet fully understood, making computational approaches for miRNA target prediction all the more important. In order to unveil miRNA functionality, it is critical to identify candidate targets. In fact, several computational approaches have been developed and experimental protocols have been proposed in order to improve the understanding of the mechanism.

Even though the first attempts to characterize miRNAs occurred almost twenty years ago [2], miRNAs were only reported as a significant class of small endogenous ncRNAs at the beginning of the last decade [1], [3], [4]. In fact, these molecules were named as miRNAs just one decade ago and since then research on miRNAs has been a focus of interest for numerous scientists worldwide, due to their powerful role in gene regulation.

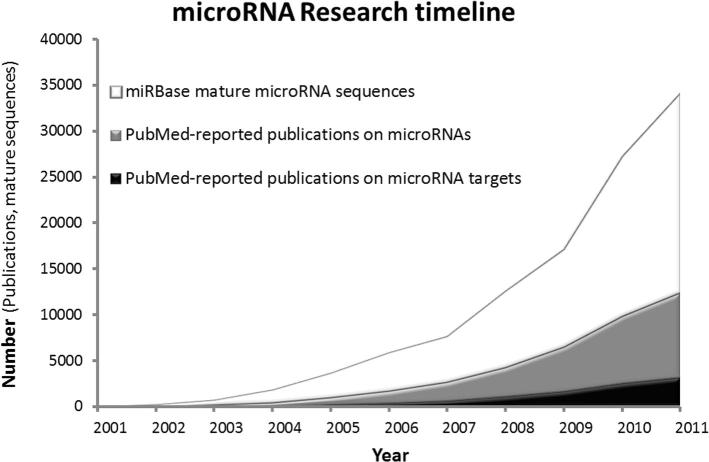

As a result, research on miRNAs has flourished in the last decade. Figure 1 shows three indicators of the research status: the number of mature miRNA sequences stored in miRBase [5], the number of publications reported in PubMed regarding miRNAs and the number of publications in PubMed with specific reference to miRNA targets. This figure not only evidences the timeline of this field, but also indicates the growing number of studies regarding miRNAs and their gene targets. It is worth noting that, according to this figure, research on gene targets of miRNAs has mainly developed after the year 2003.

Figure 1.

MicroRNA research timeline Shown in the graph is the number of mature microRNA sequences deposited in miRbase (white), PubMed-reported publications on microRNAs (gray) and microRNA targets (black), respectively.

Several reviews on miRNAs and their targets have been published focusing on the examination of biological principles [6], [7], experimental techniques and computational prediction algorithms [8], [9], [10]. Recently, various review papers have highlighted the expansion of experimental data validating miRNA–mRNA interactions [8], [9], [11], [12], [13], [14]. However, the review of miRNA target prediction algorithms is limited to the first computational algorithms which were developed based on ab initio strategies [7], [8], [10], [15].

This paper attempts to present updated information, not only regarding experimental techniques, but also prediction algorithms. We summarize the current status on miRNA target prediction, pointing out the most important considerations that should be taken into account. It is noteworthy that these considerations are addressed, not only to users of prediction tools, but also to developers. We first introduce the experimental techniques used to obtain miRNA–mRNA interactions and then present the most relevant identified characteristics of the structural interaction. Furthermore, we introduce three lines of computational algorithms for target prediction, i.e., ab initio, machine learning and hybrid, and provide examples for each line. Finally, current challenges and future directions are discussed.

Experimental data

There is no “golden rule” regarding the technique to identify or validate miRNA-target interactions. In fact, several techniques have been used to obtain experimental data that supports miRNA-target interactions [11]. Experimental data is critical, not only to distinguish a specific interaction, but also to study features that characterize miRNA–mRNA interactions and to validate the accuracy of the computational approaches proposed. It is therefore fundamental to briefly introduce the experimental data currently available regarding miRNA–mRNA interactions. In order to understand the advantages and limitations of the data derived with each experimental technique, comments for each technique are presented in order.

Experimental techniques can be classified in two classes, depending on the type of supporting information provided: direct or indirect. In addition, the experimental data can also be categorized, depending on the resultant size of dataset: individual studies or high throughput.

The individual studies can provide direct support to validate the identified candidates. Frequently, reporter genes (such as luciferase and GFP) attached to the genes of interest were used, and the expression of reporter gene was measured before and after the introduction of miRNA to the cell [16]. Such procedure can provide direct support but fails to identify the specific mRE (particularly useful to understand the structural characteristics of the interaction). Thus in order to obtain the specific mRE, reporter genes can be attached to both the original and mutated sequences of the gene of interest. Gene expression in both samples is then measured before and after miRNA transfection [16], [17]. In this way, it is possible to identify the specific site of interaction.

Moreover, the resultant experimental data size using reporter gene assays is small. Therefore a different experimental validation strategy was proposed and used in several studies [18]. In particular, expression was measured for a large number of genes through manipulating miRNA expression, either overexpression by transfection or knockdown. In the former case, a decrease in expression of target mRNAs and proteins is expected (down regulation) with increased expression of miRNAs [18], while in the latter case, an increase in expression of target mRNAs and proteins is expected (upregulation) with the miRNA expression silenced in cells [19]. Other than that, under different biological conditions, miRNA expression varies and consequently the expression of target mRNAs and proteins varies as well [20].

Experimental techniques like microarray and PCR are commonly used to measure gene expression [18]. However, since miRNA regulates not only mRNA expression but also protein levels, in doing so, targets by inhibition of mRNA translation into protein are left out. There are a few studies that used also immunoblotting to measure protein expression [19]. Furthermore, high-throughput proteomics techniques have been proposed and are used to identify both types of targets. In particular, strategies like stable isotope labelling by/with amino acids in cell culture (SILAC) [21] and pSILAC (pulsed SILAC) [22] are able to provide a high throughput dataset by using mass spectrometry (MS). Ribosome profiling is another approach for identification of both types of targets. Ribosome profiling, which is based on deep sequencing of ribosome-protected mRNA fragments [23], is a sensitive method to quantify and detect the mRNAs at the ribosome.

Nevertheless, expression-based validation strategies are indirect because the set of mRNAs/proteins with an associated microRNA induced change of expression, contains both direct targets (structural interaction) and indirect targets (the expression of the indirect target is caused by a direct target but not by the microRNA). In addition, further considerations should be taken into account depending on how the miRNA expression is manipulated. In particular, in the over-expression experiments there might be targets that, despite being affected by miRNA over-expression, do not show a high degree of down-regulation due to factors such as the saturation of the microRNA ribonucleo protein complex (miRNP) [24].

Lately, immunoprecipitation of proteins from the RISC complex has been used to identify the mRNAs where the miRNAs bind [25]. In addition, combination of crosslinking-inmunoprecipitation and high throughput sequencing has been used to isolate the mRNAs where miRNAs and protein complex bind and to obtain sequences containing the specific site of interaction [26], [27]. In particular, approaches like high-throughput sequencing of RNA isolated by crosslinking immunoprecipitation (HITS-CLIP) [26] and photoactivatable-ribonucleoside-enhanced crosslinking and immunoprecipitation (PAR-CLIP) [27] have been used to isolate, quantify, and sequence portions of mRNAs that contain the sites of miRNA–mRNA interaction. Although the sites of interaction are determined, these approaches can’t identify the specific miRNA–mRNA association experimentally, which instead is estimated by using features commonly found in experimental samples such as the seed complementary sequence.

Each of the aforementioned techniques provides an important source of information for miRNAs and genes target interaction. In particular, data with strong direct structural support is fundamental because physical interactions occur. The authors strongly advise to use data provided by direct methods to validate or train computational tools that perform the prediction based on structural characteristics.

However, indirect methods are also an important source of information. The experimental data provided contains functional targets (both direct and indirect) where the functional regulation (up or down-regulation) was induced. Evaluating the accuracy of the prediction tool (prediction of physical interaction) based on expression data does not indicate robust result since the dataset does not distinguish between indirect and direct targets. Nevertheless, a computational prediction tool can be used to distinguish direct and indirect targets in expression data sets.

Special attention should be given to the experimental data selection since indirect and direct methods perform under different assumptions. As a matter of fact, distinct target determinants between expression-based and CLIP-based data were observed in a recent study [28]. Thus, the nature of the experiment characteristics should be taken into account, in particular when the data is used to train a computational target prediction method or for validation purposes.

Databases with experimental data

The growing interest in the field has been accompanied by the continuous evolution of experimental techniques and an associated expansion of the experimental data obtained. In order to provide a common benchmark for different studies, several databases have been developed to deposit and share experimental data. In this section, the most popular databases that deposit experimental data regarding validated miRNA–mRNA interactions are presented.

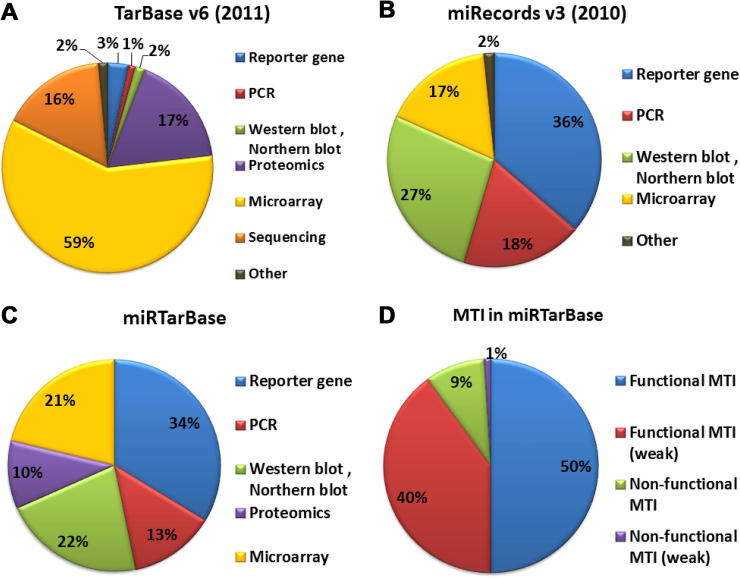

The first version of TarBase [29] was introduced in 2005 and the five previous versions of this database lacked several annotations. For example, no clear indication for records containing predicted sites (not experimentally derived) was given. However, the most recent version, Tarbase v6 [30] released in 2011, shows a number of significant improvements. In particular, several databases, such as miRecords [31], have been integrated into TarBase v6. In addition, more details are provided regarding each interaction and it is now possible to select data based on the experimental technique used, regulation type (up regulation, down regulation and unknown) and type of interaction (positive and negative). Figure 2A shows the proportions of experimental techniques used to obtain the data deposited in TarBase v6. It is worth noting that TarBase collects data provided by both individual studies and high-throughput studies. The largest dataset was obtained using high-throughput methods like microarrays, which alone provide an indirect type of validation as aforementioned.

Figure 2.

Experimental techniques used to obtain data deposited in public databases Experimental techniques used to derive human microRNA-mRNA interactions in TarBase v6–2011 (A), miRecords v3–2010 (B) and miRTarBase (C), respectively, were shown as pie chart. D. Distribution of miRNA-target interaction (MTI) types found in miRTarBase.

miRecords [31] was released in 2008 and each record in this database was manually curated. To date, three versions of miRecords have been developed with the latest release dating back to 2010. This database contains a significant amount of miRNA–mRNA interactions, most of the interactions deposited in this database have been derived from individual studies. In fact, as shown in Figure 2B, the largest proportion of deposited experimental data is obtained using reporter gene assays and most of the data included in this database has a direct type of validation. Despite the fact that the latest version was released in 2010, this database is still an important resource of interactions with strong experimental support.

Two additional databases, miRTarBase [32] and starBase [33], have been recently published. miRTarBase collects miRNA–mRNA interactions and classifies miRNA-target interactions (MTIs) into four classes including functional, functional weak (indirect experimental support), non-functional and non-functional weak, depending on the power of the experimental technique used and the type of interaction (positive or negative). Classification of MTIs is particularly useful to select experimental data according to the associated support.

Finally, starBase [33] collects data provided by high-throughput CLIP-seq, such as HITS-CLIP [26] and PAR-CLIP [27]. This type of data consists of sites of interaction for the mRNA-miRNA-Argonaute complex on a transcriptome-wide scale. Although the database initially contained data from 21 CLIP-seq experiments, the number of studies using CLIP-seq experiments is likely to grow in the next few years, considering its potentiality. Specifically, 91,124 interactions for the human are currently deposited in starBase.

Features of miRNA–mRNA interactions

The identification of common characteristics for targets and specific sites with strong experimental support is fundamental in order to unveil the rules that govern miRNA–mRNA interactions. Therefore, common characteristics found in experimental data have been extracted.

In particular, characteristics associated with the duplex miRNA-site interactions are still being explored [34]. Among the duplex features, great importance has been conferred to a region in the miRNA sequence named seed [35]. A strong complementarity to the seed region was found in a significant number of experimentally-derived sites. The seed is located in the 5′ section of the miRNA and different types of seeds sites were identified based on the length and complementarity (7mer-A1, 7mer-m8 and 8mer). Considering the importance of the seed region of interaction between miRNA and mRNA is commonly classified as the seed region and out-seed region. The out-seed region also plays an important role in the duplex interaction, either to reinforce the affinity (supplementary pairing) or to compensate for incomplete seed pairing (complementary pairing) [36]. In addition, within the out-seed region there was a preferential pairing from the 13th to the 16th nucleotide in the miRNA sequence [37]. Furthermore, additional characteristics regarding the duplex have been commonly found in sites of interaction [38], [39]. In particular, the duplex minimum free energy associated with the interaction stability represents a determinant characteristic [38]. Frequently the conservation of the mRNA site is also an important discriminant [39].

Recently, a characteristic from the duplex was extracted from a CLIP-seq data set and investigated in a few miRNAs, such as the miR124. The feature consists of the presence of a G bulge in the 6th nucleotide of the miRNA that acts as a pivot [34]. Nevertheless, further examinations on additional datasets are needed to assess this consideration.

Not only the characteristics of the duplex delineate the interaction, characteristics associated with the environment that encloses the site in the mRNA are also significant indicators. Since the mRNA has a complex structure itself, the surrounding conditions favour/disfavour the accessibility of the miRNA to the mRE and therefore influence the interaction. A number of characteristics indicate the accessibility, such as: (1) AU content in the upstream and downstream neighbourhood and (2) AU motifs in the entire mRNA (such as AUUUA pentamer). The first characteristic promotes the miRNA access to the site [40], [41], while the presence of motif signatures for RNA-binding-proteins may attenuate or enhance the regulation executed by the miRNA [42]. The presence of a GC motif downstream of the site was also extracted from sites derived experimentally [43]. In addition, features that reflect the amount of energy that must be spent in order to introduce changes from the original mRNA structure to the resulting structure after the interaction appear as important determinants [38]. In particular, the feature called ΔΔG reflects the difference in free energy between the duplex and the neighbourhood of the site initial structure [44], [45]. The specific position of the site is also an important consideration. Even though the majority of the sites have been found in the untranslated regions (UTR) of mRNAs, some mREs have also been found in the coding region [26]. However, the regulation appears to be more effective when the site of interaction is in the UTR [26]. In particular, sites in the UTR are most likely accessible if are located near the start codon or the stop codon [37]. The majority of mRE located in the UTR are found in long UTRs [46]; therefore the UTR length would seem to be another element that should be considered.

Nevertheless, none of these aforementioned characteristics are present in all the sites that have been derived experimentally [28]. One of the most commonly found characteristics is the seed, but there is a subset of sites that do not contain the seed complementarity. In fact, in the dataset derived in [26] around 27% of the identified sites did not possess seed complementary to the expressed miRNAs; such sites may bind to other miRNAs or follow different rules.

In the section Experimental Data, differences between the experimental strategies used to obtain data for miRNA–mRNA interactions were presented. Different considerations should be taken for datasets obtained from expression-based experiments and for those obtained using CLIP-seq protocols. Recently, a study [25] compared the characteristics of the interactions derived with these high-throughput strategies and noted some discrepancies. In particular, accessibility features are strongly present in data obtained with CLIP-seq techniques while duplex-related features, specifically the seed, are strong determinants for expression-based experiments. Even though there is a great overlap between the data provided by both experimental techniques, the discrepancies can be attributed to increased miRNA concentrations (overexpression) typical of expression-based experiments.

Computational algorithms

Computational algorithms for miRNA target prediction have been essential in order to identify the candidate targets and therefore the targets. Since 2003, almost one decade of development of computational miRNA target prediction algorithms has passed. Current prediction algorithms based on structural characteristics (such as the ones presented in the Features of miRNA–mRNA interactions section) can be grouped into three lines: ab initio, machine learning and hybrid approaches.

The first algorithms proposed are in the ab initio line. These algorithms perform the prediction based on the structural features extracted from data with experimental support [47], [48], [49], [50], [51], [52], [53], [54], [55]. They are based on computational models that do not use the experimental data directly. Machine learning (ML) approaches, on the other hand, use computational algorithms that rely directly on experimental data to train a classifier [56], [57], [58], [59], [60], [61], [62], [63], [64], [65], [66], [67]. In this way, the classifier is able to identify a candidate target site based on similarity to the experimental training set. Machine learning algorithms started to appear when the number of interactions with experimental support increased significantly.

Each line has an associated pitfall. For ab initio algorithms it is the high number of false positives [26] and for machine learning approaches it is the reduced number of negative interactions with experimental support (negative interactions are often not published and not recorded in databases). The set of predictions generated by ab initio algorithms contains a notable number of false positives. In order to overcome this problem, ab initio algorithms use several restrictions to retain candidates that have a high probability of being targets and filter out false positives. However with filtering, several true positives may also be discarded.

Machine learning approaches identify the probable candidates (positives) from the unlikely candidates based on the experimental data that represents positive and negative interactions. However, negative experimentally-identified interactions are usually discarded and therefore the currently available negative set (negative interactions with experimental support) is quite poor compared to the positive set.

The drawbacks of ab initio and machine learning algorithms, have led to the development of hybrid algorithms with characteristics from both lines incorporated. These hybrid algorithms integrate merits from each line in order to meet the current challenges of prediction algorithms.

The most popular ab initio, machine learning and hybrid algorithms are briefly discussed below. In addition, a summarizing table of the algorithms with several considerations can be found in the supplementary material (Table S1).

Ab initio algorithms

-

•

miRanda [47], [48] uses a weighted dynamic programming algorithm to obtain the candidate sequences. This algorithm uses a score to rank the predictions that consists of a weighted sum based on matches, mismatches and G:U wobbles. Initially, miRanda [47] used features such as seed complementarity and duplex free energy; the most recent version also takes into account a conservation measure based on the PhastCons conservation score. The algorithm and the set of target predictions are available online (http://www.microrna.org).

-

•

TargetScan [35], [37], [49]: this algorithm requires the seed complementary at least for 6 nt and considers the different seed types that have been defined, with a certain hierarchy (6mer offset < 6mer < 7mer-A1 < 7mer-m8 < 8mer) [36]. Moreover, TargetScan ranks the sites using a context score based on seed complementarity, conservation and AU content in the site vicinity. In the recent release of the latest version of TargetScan [50], a number of additional determinants have been integrated while retaining the previous considerations. In particular, a multiple linear regression trained on 74 filtered datasets was used to integrate determinants such as seed-pairing stability (SPS) and target-site abundance (TA). TargetScan is available online (http://www.targetscan.org/).

-

•

PicTar [51]: this algorithm has strict requirements regarding the seed and also takes into account the overall duplex stability based on the minimum free energy. Once the sites are aligned, the targets are ranked based on a score derived using a hidden Markov model that considers the site conservation. Predictions obtained with PicTar are available online (http://pictar.mdc-berlin.de/).

-

•

RNA22 [52] is a pattern-based discovery strategy to identify the candidate targets. First, a Markov chain is used for pattern discovery, but only the most statistically significant patterns are retained to identify target islands (areas where many statistically significant patterns map). Consequently, the target islands are paired with miRNAs. The target islands that represent candidate binding sites for miRNAs are selected based on user-imposed parameters (minimum number of base pairs, maximum number of unpaired bases and maximum allowed free energy). RNA22 is available online (http://cbcsrv.watson.ibm.com/rna22.html).

-

•

RNAhybrid [53] is an algorithm that finds the minimum free energy not only for short sequences (miRNA-mRE) as most of the previously-reported algorithms, but also for the entire miRNA–mRNA. The user can impose several restrictions, such as the number of unpaired bases and free energy allowed, to reduce the set of resulting predictions. RNAhybrid is available online (http://bibiserv.techfak.uni-bielefeld.de/rnahybrid/).

-

•

PITA [44] is a proposal that considers not only the specific duplex interaction information, but also takes into account the accessibility to the site in the mRNA. Accessibility is considered as the difference between the minimum free energy of the entire complex and the energy that originally had a short region of the mRNA near the site, ΔΔG. The user can impose different restrictions to reduce the resultant set of candidates (minimum seed size, G:U bobbles and unpaired bases). PITA is available online (http://genie.weizmann.ac.il/pubs/mir07/).

-

•

EiMMo [54] is an algorithm that scores the sites based on the conservation score and uses a Bayesian method. It infers the phylogenetic distribution for the functional sites. To characterize miRNA function, associations between the predicted targets and biochemical pathways (KEGG) are searched. EiMMo is available online (http://www.mirz.unibas.ch/ElMMo2/).

-

•

DIANA [55]: this algorithm measures the goodness of an interaction based on its specific characteristics. Each gene is weighted taking into consideration conserved as well as non-conserved sites. Moreover, a signal to noise ratio (SNR) is obtained for each interaction to estimate the number of false positives. DIANA is available online (http://diana.cslab.ece.ntua.gr/microT/).

An interesting performance comparison of the nine most popular ab initio algorithms was carried out [8] on the dataset obtained in [22]. The results evidence the usage of strict restrictions by these algorithms to reduce the number of false positives. In particular, algorithms such as PicTar, TargetScan and DIANA, have significantly-compromised sensitivity (∼10%) in order to achieve a remarkable precision (∼50%). However, the test used an expression-based dataset in which a set of miRNAs was overexpressed. As previously mentioned, when evaluating the performance on an indirect dataset, further considerations, such as the presence of indirect targets in both the positive and negative sets, and the effects caused by the overexpression like the miRNP saturation, must be taken into account.

It is also important to highlight a test performed in [68] using four ab initio algorithms (PITA, TargetScan, PicTar and miRanda) on CLIP-seq datasets obtained from Starbase. The intention of the test was to present the coverage obtained by these algorithms on CLIP-seq data. miRanda demonstrated the best sensitivity overall (66%), while TargetScan and PicTar were characterized by the lowest sensitivities (20%). This result validates (1) differences in the target determinants provided by expression-based and CLIP-based data and (2) strict restrictions imposed by ab initio algorithms like PicTar and TargetScan.

Machine learning and hybrid algorithms

Machine learning approaches appeared later than ab initio approaches. Nevertheless, the importance of these methods has grown since the data with experimental support started to grow significantly. Representatives from this line are briefly described as follows. Since machine learning algorithms strongly rely on experimental data, we also specify the size of the respective training dataset.

-

•

TargetBoost [56] consists of a boosting algorithm that assigns weights to sequence patterns of 30 nucleotides. The negative dataset used for training consists of 300 randomly-generated sequences, and the positive data set consists of 36 interactions with experimental support. The set of predictions obtained with the algorithm for the Caenorhabditis elegans can be found online, but the algorithm itself is not currently available.

-

•

miTarget [57] is an algorithm that uses a support vector machine (SVM) with an radial basis function (RBF) as kernel, to predict the candidate targets. It is based on structural, thermodynamic and positional features. The negative set used for training consists of 83 interactions with experimental support plus 163 negative interactions inferred from experimental data. The positive dataset consists of 152 interactions with experimental support. miTarget is available online (http://cbit.snu.ac.kr/xmiTarget/introduction.html).

-

•

Ensemble Algorithm [58], a post-processing step for miRanda, consists of 10 SVM (polynomial kernels). The prediction is based on features from the miRNA-mRE interactions, and features from the mRNA targets. The negative and positive datasets used for training consist of 16 and 48 experimentally-verified interactions, respectively.

-

•

NBmiRTar [59] consists of a post-processing step to miRanda. First a filter based on the folding energy is applied, followed by a filter based on the score obtained by miRanda and score obtained by a Naïve Bayes classifier. The prediction is based on structural features from the miRNA-mRE duplex features and observed sequence features. The negative dataset was composed of 38 negative interactions with experimental support and 133,316 generated target sites for artificial miRNA sequences, while the positive dataset consists of 225 interactions with experimental support.

-

•

MirTarget2 [60] uses an SVM classifier to obtain set of predictions. The features used include characteristics from the miRNA-mRE duplex and from the mRNA. The positive and negative datasets for training consists of 1017 negative interactions and 454 positive interactions with experimental support, respectively. The predicted interactions are available online (http://mirdb.org).

-

•

MiRTif [61] starts from the combination of the sets predicted by miRanda, PicTar and TargetScan. It then uses an SVM classifier (RBF kernel) based on features from the miRNA-mRE interaction. The positive and negative datasets contain 195 and 21 interactions with experimental support, respectively. In addition, the negative dataset contains 17 interactions inferred from experimental data. MiRTif is available online (http://mirtif.bii.a-star.edu.sg/).

-

•

TargetMiner [62] first selects a set of sites based on the seed complementarity. It then uses an SVM classifier (RBF kernel) based on mRNA and miRNA-mRE duplex features. The positive dataset is composed of 476 positive interactions and the negative data set contains 59 experimental interactions plus 289 inferred negative interactions. TargetMiner is available online (http://www.isical.ac.in/~bioinfo_miu/targetminer20.html).

-

•

MTar [63] first selects 3 classes of sites (5′ seed only, 5′ dominant and 3′ canonical). It then uses an artificial neural network to classify targets and non-targets based on features from the miRNA–mRNA interaction. The dataset used for training contains 340 positive miRNA–mRNA interactions and 400 negative ones. MTar is available online (http://www.rgcb.res.in/downloads/Mtar.rar).

-

•

TargetSpy [64] generates candidate zones, which are merged and a ranking of the zones is performed. This algorithm uses an automatic feature selection based on compositional, structural and base pairing features. The positive and negative dataset contains 3872 positive and 4540 negative instances, respectively, derived using the HITS-CLIP [9] protocol. TargetSpy is available online (http://www.targetspy.org/).

-

•

mirSVR, an algorithm proposed by the developers of miRanda, is a hybrid approach that uses miRanda followed by a support vector regression (SVR). In practice, miRanda is used to obtain set of predictions, which are then ranked using a machine learning approach called mirSVR [65]. mirSVR is trained based on expression changes caused by miRNA overexpression, to obtain a score for each prediction that represents an empirical probability of down regulation. Sets of predictions provided by this algorithm are available online (http://www.microrna.org).

-

•

miRror [66] is a tool based on the notion of miRNA combinatorial mode of action. The algorithm combines several ab initio predictors into a unified platform by incorporating a statistical measure. miRror is available online (http://www.proto.cs.huji.ac.il/mirror/search.php).

-

•

miREE [67] is a hybrid algorithm composed of two parts. The first part uses a genetic algorithm to generate a set of sequences that represent an optimal diverse population for binding sites. These binding sites are then mapped to mRNAs and classified as targets and non-targets using SVM (RBF Kernel), a machine learning technique. The positive and negative datasets contain 324 and 351 interactions, respectively. This algorithm is available online (http://didattica-online.polito.it/eda/miREE/).

The negative dataset is one of the principal limitations for machine learning approaches, since negative interactions are not commonly published. Several strategies have been used to overcome this drawback. In particular, the negative dataset has been expanded by using (1) random sequences, (2) predictions for artificial miRNA sequences and (3) sequences of genes that were not regulated by the miRNAs, from which the negative interaction sites were not extracted. For the first two solutions, the generated interactions do not have experimental support. Therefore, the third alternative is strongly recommended due to the presence of experimental support.

A recent comparison of the performance for five machine learning and hybrid algorithms was carried out in [67]. The comparison test was performed on a direct dataset in which each record had strong experimental support and was obtained from public databases. This comparison evidences that most of the algorithms are characterized by an unbalanced performance (sensitivity and specificity). In particular, the machine learning prediction algorithms were designed to reduce the number of false positives (principal limitation of ab initio proposals), which has significant impact on the sensitivity and the overall accuracy.

Further considerations

There has been a significant advance on development of microRNA target prediction algorithms. However, there is still room for further improvement. In particular, it is worth to integrate data derived using the lately-developed protocols (CLIP-seq), which show remarkable potential. A few approaches [64], [67] used CLIP-seq datasets to train machine learning algorithms and for validation purposes. Nevertheless, the nature of the data (high-throughput and direct validation) will most likely lead to unveil additional rules and take prediction algorithms to a different stage.

Moreover, expression-based data is also an important source of information. In fact, the use of expression-based data together with computational prediction algorithms shows significant potential, if with the right assumptions. When integrating expression data with prediction tools, it is important to associate different rules with the mechanisms of regulation [50] (mRNA abundance and mRNA stability) and distinguish between direct and indirect targets. In addition, by using expression-based data, it is possible to correlate the structural interaction with the degree of regulation exerted by the miRNA–mRNA interactions [65].

Furthermore, the interest in miRNA target prediction tools is not limited only to obtaining a set of candidate targets. Day by day, it is becoming more important to understand the miRNA functionality (functional correlation between the multiple targets both direct and indirect). In order to unveil the miRNA functionality, it is important to integrate set of predicted candidates with a different source of information and the degree of miRNA-exerted regulation in expression-based experiments is a feasible alternative. Moreover, information available in databases that contain pathways with experimental support and Gene Ontology is helpful.

Another important direction in the field is to understand the joint action mechanisms involved in transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation, cooperative action of transcription factors and miRNAs, and also the collective action of miRNAs and RNA-binding proteins.

Finally, exploring the interactions of miRNAs not only with coding RNA but also with the entire transcriptome might be helpful in order to understand not only the miRNA functionality but also the role of other RNAs such as long ncRNAs.

Conclusion

Significant progress has been made in computational algorithms for miRNA target prediction during the last decade. In particular, this evolution has been influenced by the development of experimental protocols that expanded the datasets available with experimental support. Albeit the ab initio algorithms were first proposed, with the expansion of experimental data, the use of machine learning and hybrid proposals is very promising.

Candidate target genes for prediction algorithms built under structural assumptions should be validated with experimental data with strong structural support (direct validation). The use of expression data to validate the prediction results for algorithms based on structural assumptions is susceptible to misunderstandings.

Competing interests

The authors developed one of the computational algorithms [67] but avoided any preference in this manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.gpb.2012.10.001.

Supplementary material

References

- 1.Bartel D. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee R.C., Feinbaum R.L. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell. 1993;75:843–854. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90529-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee R.C., Ambros V. An extensive class of small RNAs in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 2001;294:862–864. doi: 10.1126/science.1065329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lagos-Quintana M., Rauhut R., Lendeckel W., Tuschl T. Identication of novel genes coding for small expressed RNAs. Science. 2001;294:853–858. doi: 10.1126/science.1064921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Griffiths-Jones S., Saini H.K., van Dongen S., Enright A.J. MiRBase: tools for microRNA genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D154–D158. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cai Y., Yu X., Hu S., Yu J. A brief review on the mechanisms of miRNA regulation. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2009;7:147–154. doi: 10.1016/S1672-0229(08)60044-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mendes N.D., Freitas A.T., Sagot M.F. Current tools for the identification of miRNA genes and their targets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:2419–2433. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alexiou P., Maragkakis M., Papadopoulos G.L., Reczko M., Hatzigeorgiou A.G. Lost in translation: an assessment and perspective for computational microRNA target identification. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:3049–3055. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Witkos T.M., Koscianska E., Krzyzosiak W.J. Practical aspects of microRNA target prediction. Curr Mol Med. 2011;11:93–109. doi: 10.2174/156652411794859250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Min H., Yoon S. Got target? Computational methods for microRNA target prediction and their extension. Exp Mol Med. 2010;42:233–244. doi: 10.3858/emm.2010.42.4.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lund A.H. Experimental identification of microRNA targets. Gene. 2010;451:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jin H., Tuo W., Lian H., Liu Q., Zhu X.Q., Gao H. Strategies to identify microRNA targets: new advances. N Biotechnol. 2010;27:734–738. doi: 10.1016/j.nbt.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomson D.W., Bracken C.P., Goodall G.J. Experimental strategies for microRNA target identification. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:6845–6853. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thomas M., Lieberman J., Lal A. Desperately seeking microRNA targets. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:1169–1174. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Watanabe Y., Tomita M., Kanai A. Computational methods for microRNA target prediction. Methods Enzymol. 2007;427:65–86. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(07)27004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kiriakidou M., Nelson P.T., Kouranov A., Fitziev P., Bouyioukos C., Mourelatos Z. A combined computational-experimental approach predicts human microRNA targets. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1165–1178. doi: 10.1101/gad.1184704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Didiano D., Hobert O. Molecular architecture of a miRNA-regulated 3′ UTR. RNA. 2008;14:1297–1317. doi: 10.1261/rna.1082708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lim L.P., Lau N.C., Garrett-Engele P., Grimson A., Schelter J.M., Castle J. Microarray analysis shows that some microRNAs downregulate large numbers of target mRNAs. Nature. 2005;433:769–773. doi: 10.1038/nature03315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ji R., Cheng Y., Yue J., Yang J., Liu X., Chen H. MicroRNA expression signature and antisense-mediated depletion reveal an essential role of MicroRNA in vascular neointimal lesion formation. Circ Res. 2007;100:1579–1588. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.106.141986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pandey P., Brors B., Srivastava P.K., Bott A., Boehn S.N.E., Groene H.J. Microarray-based approach identifies microRNAs and their target functional patterns in polycystic kidney disease. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:624. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baek D., Villén J., Shin C., Camargo F.D., Gygi S.P., Bartel D.P. The impact of microRNAs on protein output. Nature. 2008;455:64–71. doi: 10.1038/nature07242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Selbach M., Schwanhausser B., Thierfelder N., Fang Z., Khanin R., Rajewsky N. Widespread changes in protein synthesis induced by microRNAs. Nature. 2008;455:58–63. doi: 10.1038/nature07228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guo H., Ingolia N.T., Weissman J.S., Bartel D.P. Mammalian microRNAs predominantly act to decrease target mRNA levels. Nature. 2010;466:835–840. doi: 10.1038/nature09267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khan A.A., Betel D., Miller M.L., Sander C., Leslie C.S., Marks D.S. Transfection of small RNAs globally perturbs gene regulation by endogenous microRNAs. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:549–555. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tan L.P.P., Seinen E., Duns G., de Jong D., Sibon O.C., Poppema S. A high throughput experimental approach to identify miRNA targets in human cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:e137. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chi S.W., Zang J.B., Mele A., Darnell R.B. Argonaute HITS-CLIP decodes microRNA-mRNA interaction maps. Nature. 2009;460:479–486. doi: 10.1038/nature08170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hafner M., Landthaler M., Burger L., Khorshid M., Hausser J., Berninger P. Transcriptome-wide identication of RNA-binding protein and microRNA target sites by PAR-CLIP. Cell. 2010;141:129–141. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wen J., Parker B.J., Jacobsen A., Krogh A. MicroRNA transfection and AGO-bound CLIP-seq data sets reveal distinct determinants of miRNA action. RNA. 2011;17:820–834. doi: 10.1261/rna.2387911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Papadopoulos G.L., Reczko M., Simossis V.A., Sethupathy P., Hatzigeorgiou A.G. The database of experimentally supported targets: a functional update of TarBase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D155–D158. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vergoulis T., Vlachos I.S., Alexiou P., Georgakilas G., Maragkakis M., Reczko M. TarBase 6.0: capturing the exponential growth of miRNA targets with experimental support. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:D222–D229. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xiao F., Zuo Z., Cai G., Kang S., Gao X., Li T. MiRecords: an integrated resource for microRNA-target interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D105–D110. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hsu S.D., Lin F.M., Wu W.Y., Liang C., Huang W.C., Chan W.L. miRTarBase: a database curates experimentally validated microRNA-target interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D163–D169. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang J.H., Li J.H., Shao P., Zhou H., Chen Y.Q., Qu L.H. starBase: a database for exploring microRNA–mRNA interaction maps from Argonaute CLIP-Seq and Degradome-Seq data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D202–D209. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stefani G., Slack F.J. A ‘pivotal’ new rule for microRNA-mRNA interactions. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19:265–266. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lewis B.P., Burge C.B., Bartel D.P. Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell. 2005;120:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bartel D.P. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136:215–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grimson A., Farh K.K., Johnston W.K., Garrett-Engele P., Lim L.P., Bartel D.P. MicroRNA targeting specificity in mammals: determinants beyond seed pairing. Mol Cell. 2007;27:91–105. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Muckstein U., Tafer H., Hackermüller J., Bernhart S.H., Stadler P.F., Hofacker I.L. Thermodynamics of RNA–RNA binding. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:1177–1182. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Altuvia Y., Landgraf P., Lithwick G., Elefant N., Pfeffer S., Aravin A. Clustering and conservation patterns of human microRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:2697–2706. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barreau C., Paillard L., Osborne B.H. AU-rich elements and associated factors: are there unifying principles? Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:7138–7150. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Enright A.J. Exiqon, Inc.; Denmark: 2008. MicroRNA research. fundamentals, reviews and perspectives. The 2008 collection booklet. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jacobsen A., Wen J., Marks D.S., Krogh A. Signatures of RNA binding proteins globally coupled to effective microRNA target sites. Genome Res. 2010;20:1010–1019. doi: 10.1101/gr.103259.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schmidt T., Mewes H.W., Stümplen V. A novel putative miRNA target enhancer signal. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6473. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kertesz M., Iovino N., Unnerstall U., Gaul U., Segal E. The role of site accessibility in microRNA target recognition. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1278–1284. doi: 10.1038/ng2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhao Y., Samal E., Srivastava D. Serum response factor regulates a muscle-specific microRNA that targets Hand2 during cardiogenesis. Nature. 2005;436:214–220. doi: 10.1038/nature03817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sandberg R., Neilson J.R., Sarma A., Sharp P.A., Burge C.B. Proliferating cells express mRNAs with shortened 3′ untranslated regions and fewer microRNA target sites. Science. 2008;320:1643–1647. doi: 10.1126/science.1155390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.John B., Enright A.J., Aravin A., Tuschl T., Sander C., Marks D.S. Human microRNA targets. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:e363. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Betel D., Wilson M., Gabow A., Marks D.S., Sander C. The microRNA.org resource. targets and expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D149–D153. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Friedman R.C., Farh K.K., Burge C.B., Bartel D.P. Most mammalian mRNAs are conserved targets of microRNAs. Genome Res. 2009;19:92–105. doi: 10.1101/gr.082701.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Garcia D.M., Baek D., Shin C., Bell G.W., Grimson A., Bartel D.P. Weak seed pairing stability and high target-site abundance decrease the proficiency of lsy-6 and other microRNAs. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:1139–1146. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lall S., Grün D., Krek A., Chen K., Wang Y.L.L., Dewey C.N.N. A genome-wide map of conserved microRNA targets in C. elegans. Curr Biol. 2006;16:460–471. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.01.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Miranda K.C., Huynh T., Tay Y., Ang Y.S.S., Tam W.L.L., Thomson A.M. A pattern-based method for the identification of microRNA binding sites and their corresponding heteroduplexes. Cell. 2006;126:1203–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kruger J., Rehmsmeier M. RNAhybrid: microRNA target prediction easy, fast and flexible. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:W451–W454. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gaidatzis D., van Nimwegen E., Hausser J., Zavolan M. Inference of miRNA targets using evolutionary conservation and pathway analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:69. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Maragkakis M., Alexiou P., Papadopoulos G., Reczko M., Dalamagas T., Giannopoulos G. Accurate microRNA target prediction correlates with protein repression levels. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10:295. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Saetrom O., Snǿve O., Saetrom P. Weighted sequence motifs as an improved seeding step in microRNA target prediction algorithms. RNA. 2005;11:995–1003. doi: 10.1261/rna.7290705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kim S.K., Nam J.W., Rhee J.K., Lee W.J., Zhang B.T. MiTarget: microRNA target-gene prediction using a support vector machine. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:411. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yan X., Chao T., Tu K., Zhang Y., Xie L., Gong Y. Improving the prediction of human microRNA target genes by using ensemble algorithm. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:1587–1593. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yousef M., Jung S., Kossenkov A.V., Showe L.C., Showe M.K. NaÏve Bayes for microRNA target predictions – machine learning for microRNA targets. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2987–2992. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang X., El Naqa I.M. Prediction of both conserved and nonconserved microRNA targets in animals. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:325–332. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yang Y., Wang Y.P., Li K.B. MiRTif: a support vector machine-based microRNA target interaction filter. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:S4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-S12-S4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bandyopadhyay S., Mitra R. TargetMiner: microRNA target prediction with systematic identication of tissue-specific negative examples. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2625–2631. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chandra V., Girijadevi R., Nair A.S., Pillai S.S., Pillai R.M. MTar: a computational microRNA target prediction architecture for human transcriptome. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:S2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-S1-S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sturm M., Hackenberg M., Langenberger D., Frishman D. TargetSpy: a supervised machine learning approach for microRNA target prediction. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:292. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Betel D., Koppal A., Agius P., Sander C., Leslie C. Comprehensive modelling of microRNA targets predicts functional non-conserved and non-canonical sites. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R90. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-8-r90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Friedman Y., Naamati G., Linial M. MiRror: a combinatorial analysis web tool for ensembles of microRNAs and their targets. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:1920–1921. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Reyes∼Herrera P.H., Ficarra E., Acquaviva A., Macii E. miREE: miRNA recognition elements ensemble. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:454. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kumar A., Wong A.K., Tizard M.L., Moore R.J., Lefèvre C. miRNA_Targets: a database for miRNA target predictions in coding and non-coding regions of mRNAs. Genomics. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2012.08.006. pii:S0888-7543(12)00175-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.