Abstract

Background

Bendamustine may be a potential treatment option for patients with myeloma, but little is known about the utility of bendamustine as a salvage treatment, especially in Asian patients.

Methods

We performed a multicenter retrospective study of patients with relapsed or refractory myeloma who received bendamustine and prednisone.

Results

The records of 65 heavily pre-treated patients, who had undergone bortezomib and lenalidomide treatment (median number of previous treatments: 5), were analyzed. The median time from diagnosis to bendamustine treatment was 3.8 years, and the median patient age was 63 years (range, 38‒77 yr). The responses to the last treatment before bendamustine were refractory disease (N=52, 80%) or disease progression from partial response (N=13, 20%). Twenty-three patients responded to the treatment, with an overall response rate of 35% (23/65), and the median number of bendamustine treatment cycles was two (range, 1‒5 cycles). The median overall survival after bendamustine treatment was 5.5 months and the overall survival rate in responders to bendamustine was significantly better than that in non-responders (P=0.036).

Conclusion

Bendamustine may be a potential salvage treatment to extend survival in a select group of heavily pre-treated patients with relapsed or refractory myeloma.

Keywords: Myeloma, Bendamustine, Response, Toxicity, Survival

INTRODUCTION

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a plasma cell neoplasm characterized by the accumulation of clonal bone marrow plasma cells that produce abnormal monoclonal immunoglobulin which can be detected in the blood and/or urine; MM accounts for approximately 10% of all hematologic malignancies [1]. Survival outcomes for patients with MM have substantially improved over the last two decades due to treatment with high-dose chemotherapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT), as well as novel agents such as bortezomib and immunomodulatory drugs (IMIDs) that have become available in both the upfront and relapse settings [2,3,4]. Nevertheless, almost all patients ultimately relapse and become refractory to salvage treatments with few options for management. Many new drugs such as carfilzomib and pomalidomide have been approved for the treatment of relapsed or refractory MM patients previously treated with bortezomib and lenalidomide. However, their use remains limited due to their high cost in many countries, including Korea. Accordingly, treatment options for patients who relapse after bortezomib and IMIDs have been limited in Korea, especially for elderly patients who are not eligible for stem cell transplantation [5,6,7].

Since its approval for MM patients in 2011, bendamustine has emerged as a treatment option for patients with relapsed or refractory MM in Korea. A bi-functional alkylating agent with structural similarities to both alkylating agents and purine analogues, bendamustine induces anti-tumor effects by causing intra- and inter-strand cross-links between DNA bases that are more extensive and durable than those caused by other alkylating agents [8,9]. Thus, bendamustine shows incomplete cross-resistance with cyclophosphamide and melphalan [10,11,12]. Since its development in East Germany, bendamustine, alone or in combination with steroids or other novel agents, has been used in the treatment of patients with MM in the clinical trial setting. However, there is limited data available regarding the efficacy of bendamustine in an unselected, real-life population with relapsed or refractory MM. Thus, we analyzed treatment outcomes in heavily pre-treated patients who received bendamustine during clinical practice for relapsed or refractory myeloma.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

The Korean Multiple Myeloma Working Party proposed a nationwide retrospective study to examine bendamustine as a salvage treatment for heavily pre-treated patients with relapsed or refractory MM (KMM125 study). The primary endpoints were overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) after bendamustine treatment. The secondary endpoints were overall response rate (ORR), which was categorized as either complete response (CR), very good partial response (VGPR), or partial response (PR); and treatment-related hematologic and non-hematologic toxicities. Response was assessed using the International Myeloma Working Group uniform response criteria [13,14,15]. Patients who satisfied all of the following criteria were included: 1) pathologically diagnosed with MM, 2) received at least two kinds of treatment prior to bendamustine-containing treatment between 2011 and 2013, and 3) underwent at least one cycle of bendamustine. Medical record reviews and data collections were performed by investigators from participating institutes. Response rates and toxicities were analyzed in April 2014, and the final analysis, including survival outcomes, was performed after the final survival status update in December 2015. Given that the study was a retrospective analysis with the purpose of a nationwide survey, the sample size calculation was based on the total number of patients who satisfied the inclusion criteria during the study period. All aspects of the study were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Samsung Medical Center (No. 2012-07-042), and by each IRB of the participating institutions. The requirement for individual informed consent was waived due to the minimal risk that the study posed to participants.

Treatment and evaluation

Treatment consisting of bendamustine and the steroid prednisone was administered every 4 weeks (28-day cycles). Bendamustine was administered intravenously at a dose of 120 mg/m2 per day on days 1 and 2, in combination with prednisone at a dose of 60 mg/m2 per day, or a fixed dose of 100 mg per day, on days 1–4. The response evaluation was repeated every cycle with serum and 24-hour urine electrophoresis and immunofixation, and a serum-free light chain assay. The ORR was based on the best response during treatment; therefore, if a patient showed disease progression after responding to treatment before the end of treatment, they were counted as a responder. Response was assessed according to the International Uniform Response Criteria for Multiple Myeloma [13,14]. Toxicities were graded according to the National Cancer Institute's Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 3.0, and the maximum toxicity grade per patient was recorded.

Statistical analysis

Fisher's exact test was used for categorical data and survival outcomes were calculated using Kaplan-Meier curves and compared using the log-rank test. OS after bendamustine treatment was calculated from the start date of bendamustine treatment to the date of any cause-related death or the last follow-up date. PFS after bendamustine treatment was described as survival duration between the start date of bendamustine treatment to the date of relapse or progression or any kind of death. P-value<0.05 was considered to be significant, and the analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS v.18.0).

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

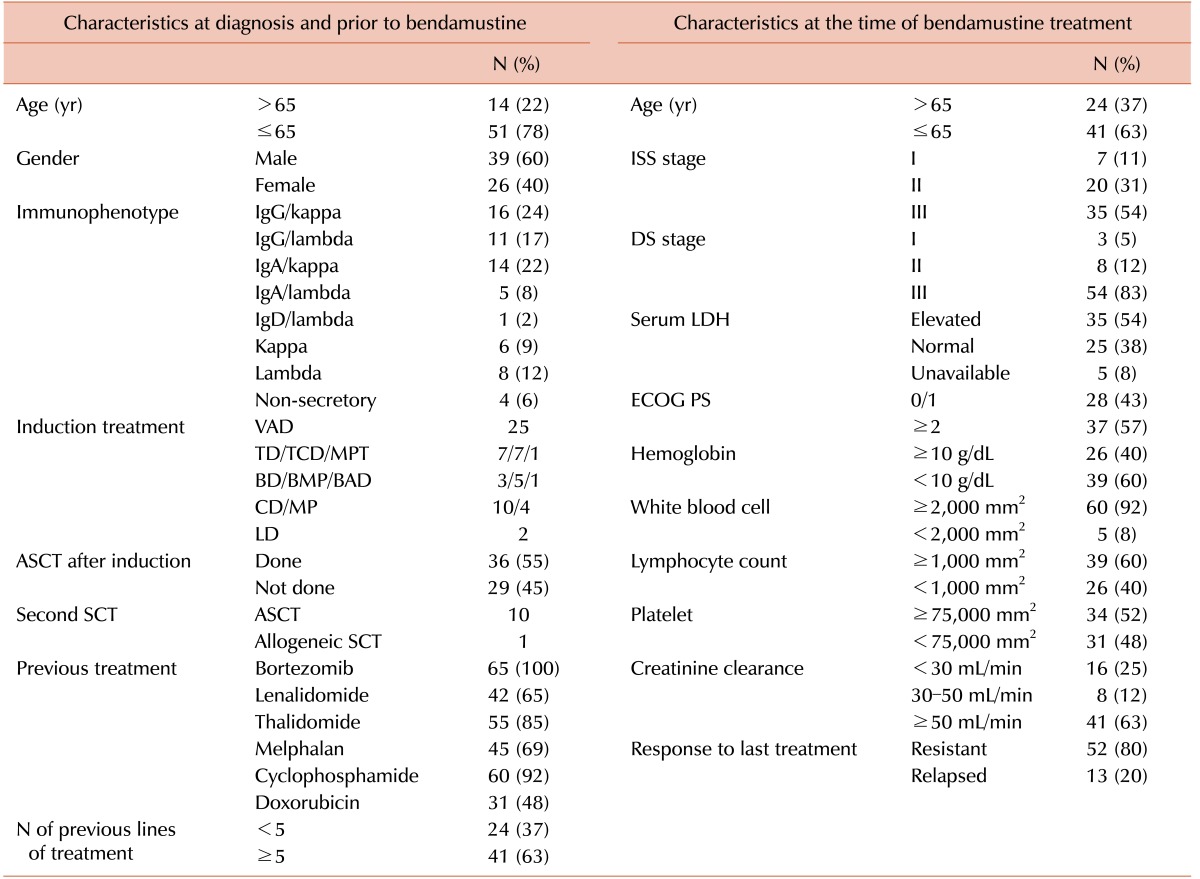

We collected data for 65 patients who received bendamustine treatment between November 2011 and September 2013 at 10 hematological institutions in Korea. The median age at initial diagnosis of MM was 57 years (range, 37–75 yr), and the male-to-female ratio was 1.5:1. All patients had ≥10% plasma cells in the bone marrow at diagnosis, and 23 patients had >50% of plasma cells. The most common immunophenotype was IgG/kappa (Table 1). Cytogenetic information at diagnosis, based on conventional cytogenetics and fluorescence in-situ hybridization, was available only for 41 patients. Of these, 26 patients showed abnormal cytogenetics such as deletion 13q (N=5), t(11:14) (N=4), t(4:14) (N=4), t(14:16) (N=2), and deletion 17p (N=2). Thirty-six patients who were diagnosed with MM between November 2001 and April 2013 underwent ASCT after induction treatment, such as VAD (vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone), and thalidomide-containing treatment (Table 1). The median number of previous treatments was five (range, 2–12), and the median time to bendamustine treatment was 3.8 years (range, 0.2–10.4 yr). As a result, the median age at the time of the first bendamustine treatment cycle was 63 years (range, 38–77 yr), and a substantial number of patients had advanced disease with impairment of renal and bone marrow function (Table 1). The responses to the last treatment before bendamustine treatment were refractory disease (N=52, 80%) or disease progression from partial response (N=13, 20%).

Table 1. Clinical and laboratory characteristics of the patients.

Abbreviations: ASCT, autologous stem cell transplantation; BAD, bortezomib, doxorubicin, dexamethasone; BD, bortezomib, dexamethasone; BMP, bortezomib, melphalan, prednisolone; CD, cyclophosphamide, dexamethasone; DS, Durie-Salmon; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; ISS, International Staging System; LD, lenalidomide, dexamethasone; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; MP, melphalan, prednisolone; MPT, melphalan, prednisolone, thalidomide; PS, performance status; TD, thalidomide, dexamethasone; TCD, thalidomide, cyclophosphamide, dexamethasone; SCT, stem cell transplantation; VAD, vincristine, doxorubicin, dexamethasone.

Response and toxicity

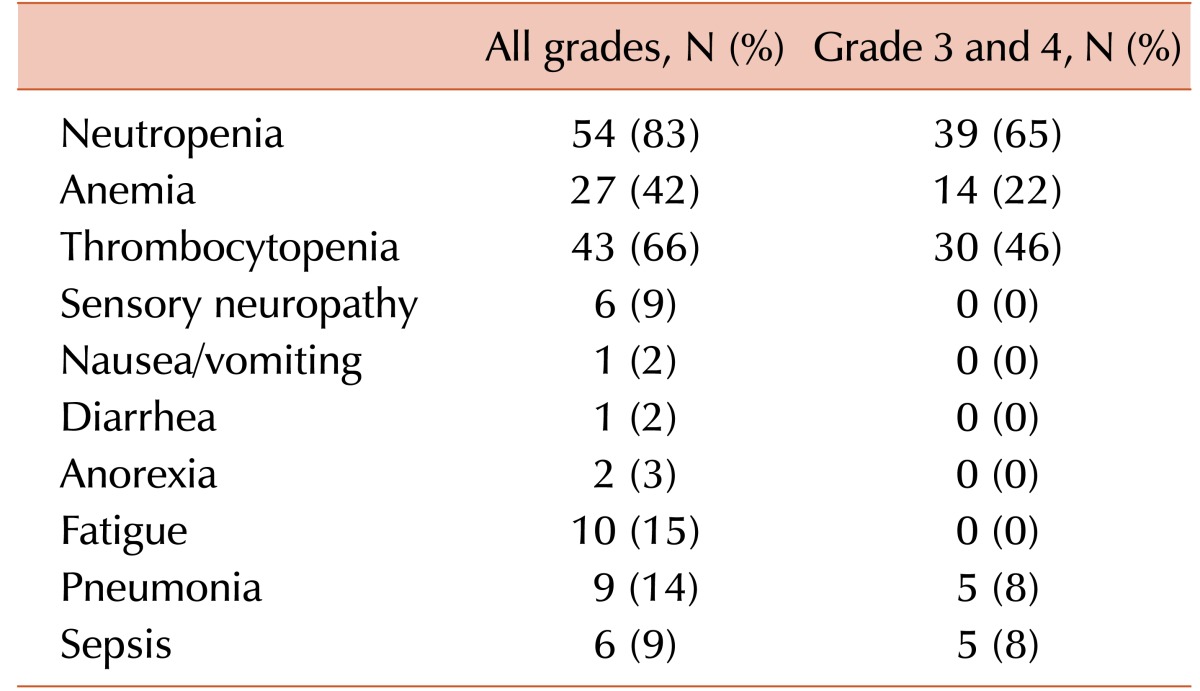

The median dosage of bendamustine was 120 mg/m2, although, in five patients, the dose of bendamustine was reduced to 100 mg/m2 in subsequent cycles of treatment based on the physician's decision. Out of 65 patients, the response to treatment was evaluated in 62 patients; the response of three patients who died due to sepsis after the first bendamustine treatment cycle was not evaluated. Based on the best response achieved, 23 patients responded to the treatment; this included one case of CR, five cases of VGPR and 17 cases of PR, for an ORR of 35% (23/65). However, 18 patients showed early disease progression during treatment. The median number of bendamustine treatment cycles was two (range, 1–5 cycles). Reasons for discontinuation included lack of response (stable disease or progressive disease, N=39), infectious complications (N=10), and other reasons (N=16), such as non-infectious complications and early discontinuation due the high cost of treatment for uninsured patients. Based on the maximum toxicity in each patient during treatment, hematologic toxicities were the most commonly observed toxicities (Table 2). Grade 3/4 neutropenia was found in 65% of patients, although most non-hematologic toxicities were less than grade 3. Frequent neutropenia and frailty in the majority of patients due to significant previous treatments and disease progression meant that infectious complications were not uncommon, and 10 patients died due to infectious complications of pneumonia (N=5) and sepsis (N=5).

Table 2. Toxicity profiles.

Survival outcome

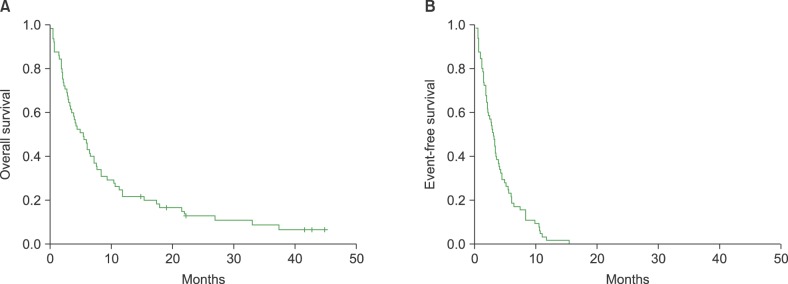

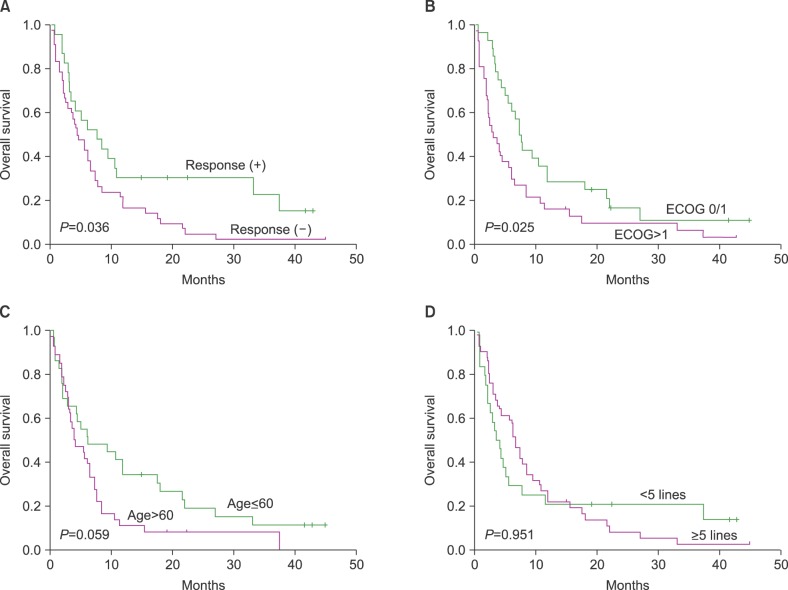

At the final update, 59 patients had died and only six patients were still alive. Thus, the median OS and PFS after bendamustine treatment was 5.5 months (95% confidence interval [CI]: 3.5–7.5 mo) and 3.1 months (95% CI: 2.4–3.8 mo), respectively (Fig. 1). Even though the median OS was short, 14 patients (22%) lived longer than 12 months after they started bendamustine treatment (range, 12–45 mo). The OS in patients who responded to bendamustine was significantly better than that of patients who did not (P=0.036, Fig. 2). Performance status was significantly associated with OS, and a trend towards improved OS was also observed in patients≤60 years old (Fig. 2). However, the median number of treatment lines prior to bendamustine treatment was not associated with OS (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1. (A, B) Median overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) after bendamustine treatment was 5.5 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 3.5–7.5 mo) and 3.1 months (95% CI, 2.4–3.8 mo), respectively.

Fig. 2. (A) The OS of patients who responded to bendamustine was significantly better than that of patients who did not. (B) Performance status at the time of bendamustine treatment was significantly associated with OS. (C) Patients ≤60 years old at the time of bendamustine treatment showed a trend towards better OS. (D) The median number of lines prior to bendamustine treatment was not associated with OS.

DISCUSSION

In this study, bendamustine combined with prednisone resulted in an ORR of 35% (23/65), including one case of CR and five cases of VGPR. However, the majority of patients showed early progression or treatment-related events, yielding a median PFS of 3.1 months and a median OS of 5.5 months after bendamustine treatment (Fig. 1). The treatment outcome in our study appeared to be less significant than outcomes achieved in recent clinical trials that combined bendamustine with novel agents such as lenalidomide and bortezomib [16,17]. However, the outcome of our study population may not be comparable to those clinical trials for several reasons. First, our study population reflected unselected, heavily pre-treated real-life patients that were encountered in our clinical practice. As a result, more than half of the patients had a poor performance status (≥Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group [ECOG] grade 2), and a substantial number of patients had uni- or bi-lineage cytopenia as well as impaired renal function at the time of bendamustine treatment (Table 1). Second, more than 60% of patients underwent at least five lines of treatment, including bortezomib and IMIDs, prior to bendamustine treatment. Furthermore, 80% of patients were resistant to their last treatment; therefore, the likelihood of treatment resistance may have been higher in our patients than those enrolled in clinical trials. Third, bendamustine was used only in combination with prednisone because the combination with other novel agents was not allowed in clinical practice in Korea. The limited use of bendamustine may also have affected outcome, since a lack of national insurance coverage for bendamustine prevented continuous treatment, even in responders. For these reasons, the outcome of bendamustine treatment in this study should be interpreted cautiously.

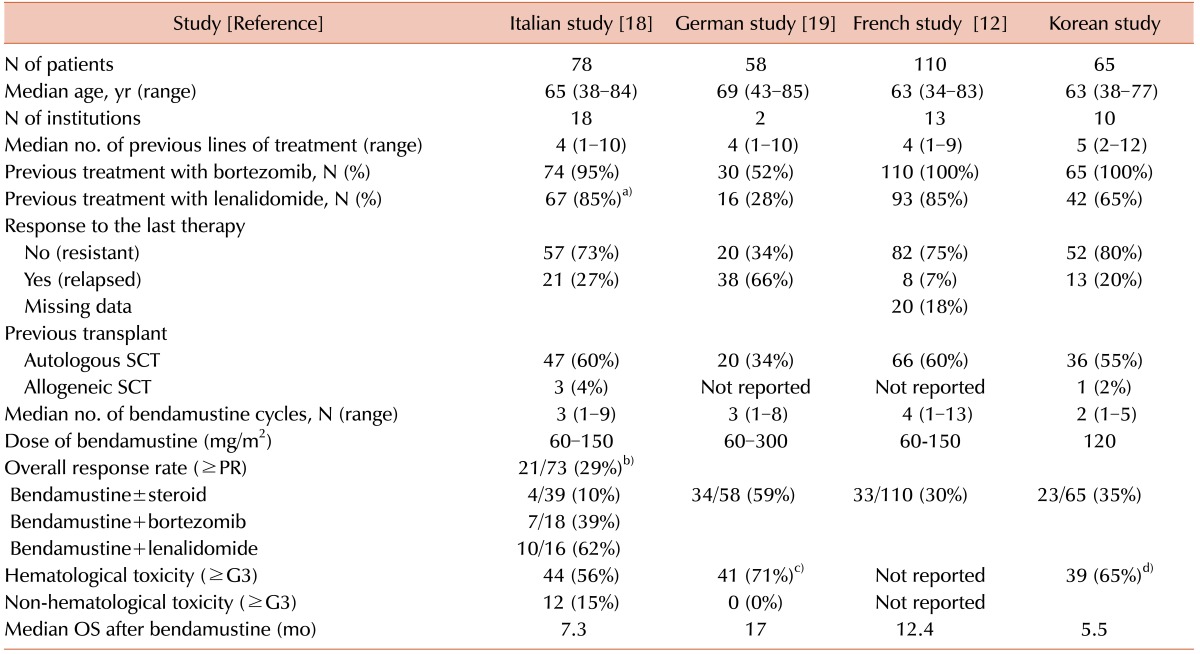

When we compared our results with previously reported series that evaluated outcome with bendamustine in unselected, heavily pre-treated patients with relapsed or refractory MM, the response rate and survival outcomes of our patients were comparable (Table 3). A previous study based on the French compassionate-use program reported overall response rates and survival outcomes that were similar to those in our study [12]. Patient characteristics at the time of bendamustine treatment were also similar in terms of previous treatments and the percentage of patients who were refractory to their last treatment (Table 3). Recently, an Italian study also reported an ORR of only 29% and a median OS of 7.3 months following various bendamustine-containing salvage treatments in an unselected patient population that more accurately reflected patients encountered in clinical practice [18]. Although another retrospective study reported a better outcome with an ORR of 59% and a median OS of 17 months, the patient characteristics in that study were different to those in other studies, including ours, in terms of previous treatments and the percentage of patients refractory to their last treatment [19].

Table 3. Comparisons between multicenter studies of bendamustine treatment for relapsed or refractory myeloma.

a)This study just described the percentage of patients exposed to immunomodulatory drugs. b)The ORR of the study included the response rates of different regimens. c)The hematologic toxicity was based on grade 3/4 anemia. d)The hematologic toxicity was based on grade 3/4 neutropenia.

Abbreviations: G, grade; OS, overall survival; PR, partial response; SCT, stem cell transplantation.

In our study, the incidence of grade 3/4 neutropenia (65%) was higher than that of previous studies (Table 3). As a result, 10 patients died due to infectious complications associated with pneumonia (N=5) and sepsis (N=5). This high incidence of infectious complications may be associated with the frequent occurrence of neutropenia and the poor health of the patients due to underlying diseases and comorbidities. However, the bendamustine dosage may also have contributed, since our patients received 120 mg/m2 of bendamustine in combination with prednisolone. Accordingly, dosage modifications as well as active prophylaxis against infections should be considered when bendamustine is used in heavily pre-treated frail patients with MM. At the time of the final survival status update, only six patients were alive and the median OS after bendamustine treatment was 5.5 months. However, patients who responded to bendamustine showed a significant survival benefit compared with patients who did not (Fig. 2). Furthermore, 14 patients (22%) had survived >12 months since they started bendamustine treatment (range, 12–45 mo), including the six patients who were still alive at the final follow-up. Some of the patients could be rescued by additional salvage treatments; this indicated that the extended OS after bendamustine was possible even after relapse or progression. Accordingly, bendamustine treatment could be used as a bridge treatment until newer treatments become available. The association of performance status and age at the time of bendamustine treatment with better OS also suggests that bendamustine treatment should be considered for salvage treatment in heavily pre-treated patients with MM, especially in patients≤60 years old, who have a good performance status.

In conclusion, bendamustine may be effective in a select group of patients with relapsed or refractory MM. It represents a potential bridge treatment for heavily pre-treated patients, and may extend survival until newer treatment options become available. To our knowledge, this is the first report of the efficacy of bendamustine in Asian patients with MM. Further prospective studies are needed to confirm the efficacy of bendamustine-based treatments in Asian patients with MM.

Footnotes

This study was supported by a grant from the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI) funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (grant number: HI14C1324).

Authors' Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest: No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

References

- 1.Raab MS, Podar K, Breitkreutz I, Richardson PG, Anderson KC. Multiple myeloma. Lancet. 2009;374:324–339. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60221-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kumar SK, Rajkumar SV, Dispenzieri A, et al. Improved survival in multiple myeloma and the impact of novel therapies. Blood. 2008;111:2516–2520. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-116129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pulte D, Gondos A, Brenner H. Improvement in survival of older adults with multiple myeloma: results of an updated period analysis of SEER data. Oncologist. 2011;16:1600–1603. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2011-0229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cavo M, Brioli A, Petrucci A, et al. Bortezomib with thalidomide plus dexamethasone compared with thalidomide plus dexamethasone as induction therapy before, and consolidation therapy after, double autologous stem-cell transplantation in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: a randomised phase 3 study. Lancet. 2010;376:2075–2085. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61424-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim HJ, Yoon SS, Eom HS, et al. Use of lenalidomide in the management of relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma: expert recommendations in Korea. Blood Res. 2015;50:7–18. doi: 10.5045/br.2015.50.1.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim SJ, Kim K, Kim BS, et al. Clinical features and survival outcomes in patients with multiple myeloma: analysis of web-based data from the Korean Myeloma Registry. Acta Haematol. 2009;122:200–210. doi: 10.1159/000253027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee JH, Lee DS, Lee JJ, et al. Multiple myeloma in Korea: past, present, and future perspectives. Experience of the Korean Multiple Myeloma Working Party. Int J Hematol. 2010;92:52–57. doi: 10.1007/s12185-010-0617-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leoni LM, Bailey B, Reifert J, et al. Bendamustine (Treanda) displays a distinct pattern of cytotoxicity and unique mechanistic features compared with other alkylating agents. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:309–317. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tageja N, Nagi J. Bendamustine: something old, something new. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2010;66:413–423. doi: 10.1007/s00280-010-1317-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strumberg D, Harstrick A, Doll K, Hoffmann B, Seeber S. Bendamustine hydrochloride activity against doxorubicin-resistant human breast carcinoma cell lines. Anticancer Drugs. 1996;7:415–421. doi: 10.1097/00001813-199606000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Balfour JA, Goa KL. Bendamustine. Drugs. 2001;61:631–638. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200161050-00009. discussion 639-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Damaj G, Malard F, Hulin C, et al. Efficacy of bendamustine in relapsed/refractory myeloma patients: results from the French compassionate use program. Leuk Lymphoma. 2012;53:632–634. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2011.622422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Durie BG, Harousseau JL, Miguel JS, et al. International uniform response criteria for multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2006;20:1467–1473. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kyle RA, Rajkumar SV. Criteria for diagnosis, staging, risk stratification and response assessment of multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2009;23:3–9. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anderson KC, Kyle RA, Rajkumar SV, et al. Clinically relevant end points and new drug approvals for myeloma. Leukemia. 2008;22:231–239. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2405016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lentzsch S, O'Sullivan A, Kennedy RC, et al. Combination of bendamustine, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone (BLD) in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma is feasible and highly effective: results of phase 1/2 open-label, dose escalation study. Blood. 2012;119:4608–4613. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-12-395715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ludwig H, Kasparu H, Leitgeb C, et al. Bendamustine-bortezomib-dexamethasone is an active and well-tolerated regimen in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. Blood. 2014;123:985–991. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-08-521468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Musto P, Fraticelli VL, Mansueto G, et al. Bendamustine in relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma: the "real-life" side of the moon. Leuk Lymphoma. 2015;56:1510–1513. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2014.982644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stöhr E, Schmeel FC, Schmeel LC, Hänel M, Schmidt-Wolf IG German Refractory Myeloma Study Group. Bendamustine in heavily pre-treated patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2015;141:2205–2212. doi: 10.1007/s00432-015-2014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]