Abstract

Background

Since cell turnover in the hematopoietic system constitutes a major source of uric acid (UA) production, we investigated whether hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is associated with significant changes in serum UA levels in patients with hematological disorders.

Methods

Patients who underwent HSCT at our institution between 2001 and 2012 were retrospectively enrolled. Serum UA levels at 3 months before, 1 week before, and 3 months and 1 year after HSCT were examined.

Results

Complete clinical and laboratory information including data regarding UA levels was available for 93 patients. At baseline, the mean UA level was 4.9±2.1 mg/dL, with an overall prevalence of hyperuricemia of 15% (defined as serum UA>6.8 mg/dL). Mean UA levels tended to be higher in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (4.8±2.0 mg/dL) and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (5.1±2.3 mg/dL) and lower in patients with aplastic anemia (mean, 4.2±1.8 mg/dL). UA levels dropped during myeloablative conditioning, reaching a nadir on the day of HSCT (3.27±1.4 mg/dL). Over the 3 months following HSCT, UA levels rose sharply (5.0±2.1 mg/dL) and remained stable up to 1 year after HSCT (5.5±1.6 mg/dL). UA levels in HSCT recipients at 12 months correlated with those of their respective graft donors (Pearson r=0.406, P=0.001).

Conclusion

HSCT is associated with significant changes in uric acid levels in patients with hematologic disorders.

Keywords: Uric acid, Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, Bone marrow

INTRODUCTION

Degradation of purine nucleotides during cell turnover contributes to endogenous production of uric acid (UA). Constant turnover of hematopoietic cells constitutes a major site of purine salvage and metabolism [1]. With normal UA removal by the kidney, serum UA levels should correlate with cell turnover in the hematopoietic system. Accordingly, pathologically accelerated cell turnover in patients with hematologic malignancies would increase the delivery of purines to the liver where hepatic xanthine oxidase metabolizes them into UA, resulting in increased serum UA levels. Indeed, elevated UA levels in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) are predictive of a poor outcome [2,3]. Conversely, a reduced cell turnover in bone marrow (BM) is associated with lower serum UA levels [4,5].

Successful hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) restores blood cell turnover in BM. HSCT with associated radical changes may significantly affect serum UA levels and may even normalize levels in patients with hematological diseases. To date, the long-term effects of HSCT on serum UA levels have not been fully elucidated [6]. In this study, we aimed to investigate the changes in UA levels over time in patients who underwent allogeneic HSCT.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

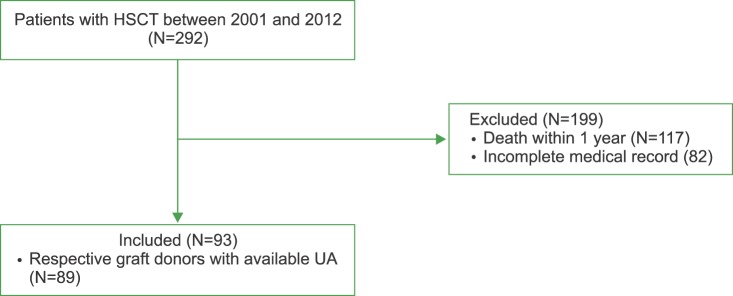

The medical records of 292 patients who underwent allogeneic HSCT at Seoul National University Hospital between 2001 and 2012 were reviewed. Baseline clinical characteristics, BM pathology, karyotypes, and serum UA levels were ascertained by reviewing the electronic medical records. Within 1 year of HSCT, 117 patients died. Major causes of death were septic shock (N=42, 35.9%), graft-versus-host disease (N=25, 21.4%), and infection (N=19, 16.2%). Therefore, a comprehensive medical record was available in 93 patients (Fig. 1). Serum UA levels at day 90±14 before HSCT, on the day of transplantation, and at days 90±14 and 365±14 post-HSCT were examined. Of note, per the HSCT protocol at our institution, all patients received allopurinol 300 mg daily during myeloablative conditioning (i.e., 7 days before HSCT) as prophylaxis for tumor lysis syndrome. Patients also received cyclosporine as prophylaxis for graft-versus-host disease.

Fig. 1. Patient flow.

Abbreviations: UA, uric acid; HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul National University Hospital. Obtaining informed consent was waived by the Review Board as the study involved minimal risk and no identifiable information was used.

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean±SD for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables. Student's t-tests or the Mann-Whitney test for continuous variables was performed as appropriate. The changes in UA levels over time were evaluated using repeated measure analysis of variance (ANOVA). The correlation between recipient UA levels at 1 year after HSCT and donor UA levels were evaluated using Pearson's correlation. P-values≤0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS (statistics version 21.0, Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

Clinical characteristics of patients

Baseline characteristics of patients who underwent HSCT (N=93) are reported in Table 1. The mean age was 40.5±11.6 years. Acute myeloid leukemia (N=23) was the most common reason for HSCT, followed by severe aplastic anemia (N=15), acute lymphoblastic leukemia (N=15), and chronic myeloid leukemia (N=15). No patient had a prior history of gout.

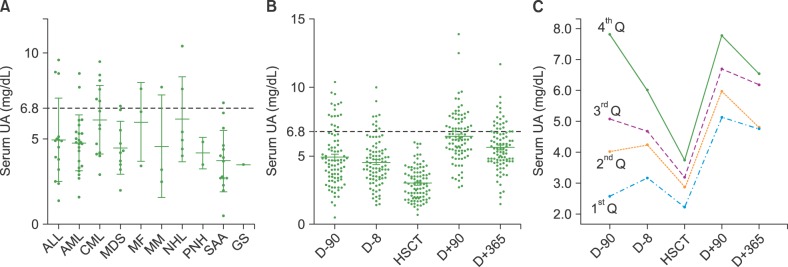

Table 1. Demographics and baseline characteristics of patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Data are expressed as mean±SD for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables.

UA levels after HSCT

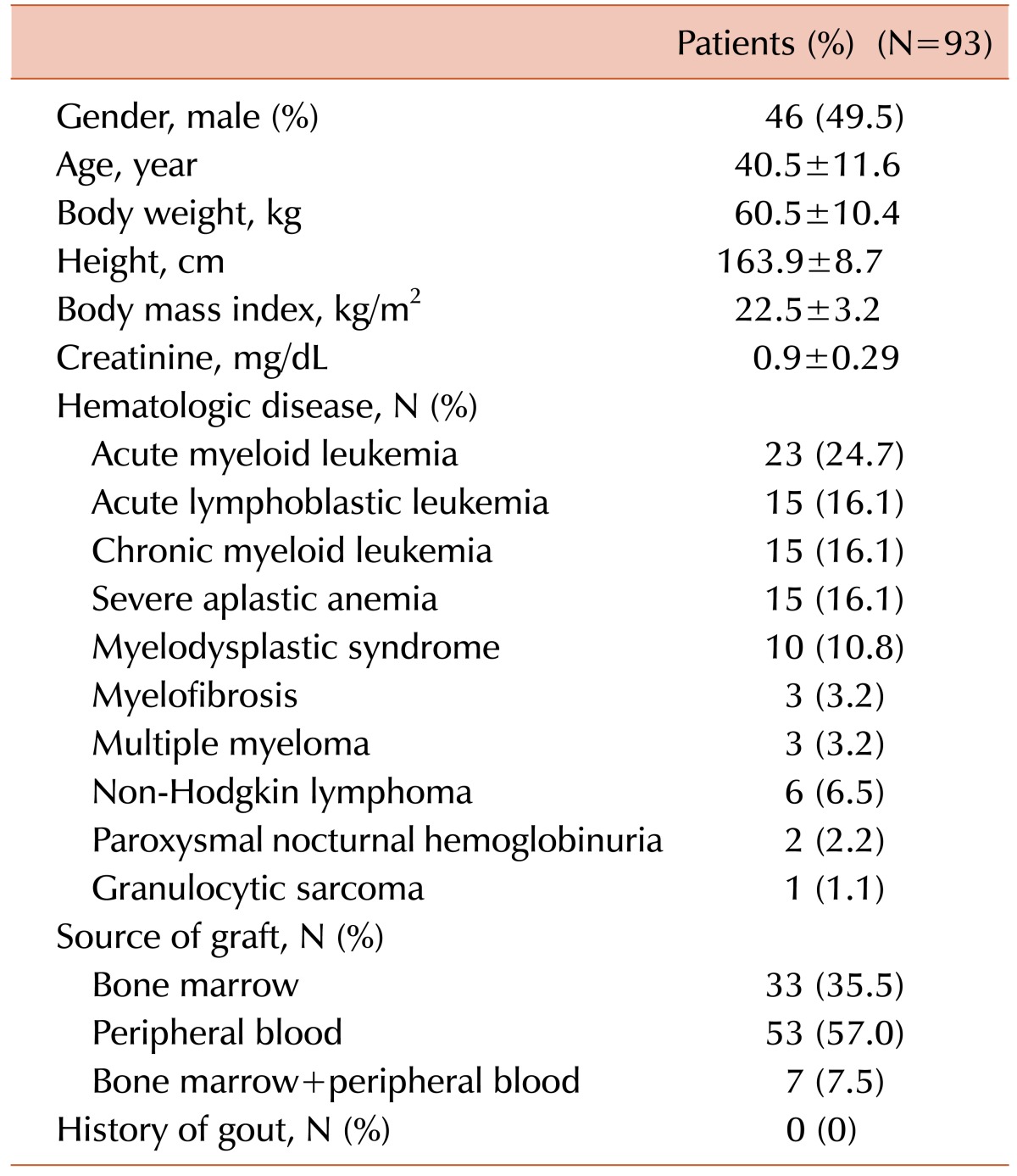

The mean baseline UA level was 4.9±2.1 mg/dL. Similar baseline UA levels were observed in aplastic anemia patients (mean, 4.2±1.8 mg/dL). Mean UA levels tended to be higher in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia (6.4±2.0 mg/dL) and non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL, 5.1±2.3 mg/dL) (Fig. 2A). UA levels dropped significantly during myeloablative conditioning, reaching a nadir on the day of HSCT (3.3±1.4, P<0.001) (Fig. 2B). To better track UA levels over time, patients were grouped into quartiles based on their baseline serum UA levels in an ascending order. During myeloablative conditioning, UA levels in the 4th quartile showed more dramatic changes than those in the 1st quartile. In the 3 months following HSCT, UA levels in all quartiles rose and remained relatively stable over time. UA levels changed differently between the groups over time (P<0.001) (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2. Changes in serum uric acid levels over time after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. (A) Baseline serum UA levels in patients according to their underlying hematologic diseases. (B) UA levels before and after HSCT. (C) Changes in UA levels over time. Patients were grouped into quartiles based on their baseline serum UA levels in ascending order. Abbreviations: HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; UA, uric.

Abbreviations: HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; UA, uric acid; Q, quartile; ALL, acute lymphoblastic leukemia; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; MF, myelofibrosis; MM, multiple myeloma; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; PNH, paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria; SAA, severe aplastic anemia; GS, granulocytic sarcoma.

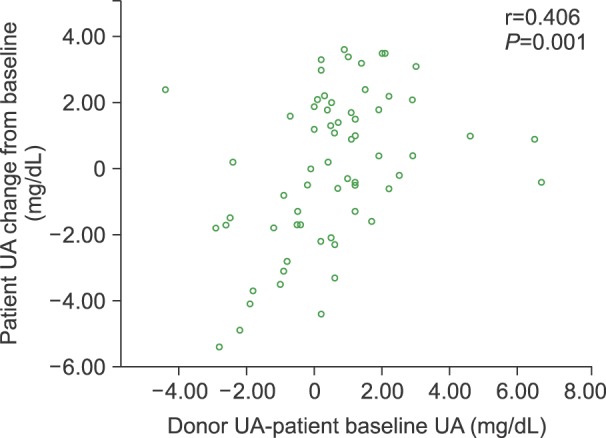

Correlation of UA levels between donors and recipients

For 89 patients, UA levels of their respective hematopoietic stem cell donors were available. The UA levels in patients at 12 months after HSCT correlated significantly with those of their respective graft donors (Pearson's r=0.406, P=0.001) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Correlation of post-transplant uric acid (UA) levels between HSCT recipients and respective donors. UA levels in 89 patients at 12 months after HSCT were correlated with levels of their corresponding graft donors. Correlations were compared using Pearson's coefficient.

Abbreviation: HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report to demonstrate the changes in UA levels over time in patients who underwent allogeneic HSCT. Since the cell turnover in BM is a major contributor to endogenous production of UA, serum UA levels should closely correlate with cell turnover in the hematopoietic system. Indeed, baseline UA levels appeared to reflect cell turnover rate within and outside BM in patients with hematological diseases, with the lowest UA levels observed in patients with aplastic anemia and the highest in those with chronic myeloid leukemia (Fig. 2A). Higher UA levels might reflect increased pathological cell turnover; in fact, increased UA levels have been shown to be associated with a worse outcome in acute myeloid leukemia [3]. Conversely, lower UA levels might be associated with disease activity or a worse outcome in patients with aplastic anemia, which is characterized by hypocellular and possibly hypoactive BM. Accordingly, restoration of normal cell turnover after HSCT tended to normalize the serum UA levels; both elevated and decreased UA levels in recipients normalized at 1 year after HSCT (Fig. 2C). Of note, 235 (80.5%) of 292 patients underwent a follow-up BM study. Of those, 30 (12.8%) exhibited hypoplasia or aplasia, whereas 157 (66.8%) had normal BM. Disease recurred in 48 (20.4%) patients. UA levels tended to be different between patients with hypoplastic or aplastic BM (4.31±1.92 mg/dL), normal BM (4.76±2.13 mg/dL), and disease recurrence in BM (5.01±3.82 mg/dL) (data not shown). As to whether normalization of the serum UA level is a useful biomarker of successful long term engrafting needs to be investigated in a larger prospective cohort.

It is conceivable that the rate of cell turnover in the hematopoietic system varies around a preset individual baseline, depending on cell demand in the periphery [7]. HSCT replaces recipient BM cells with donor cells, and would reset the intrinsic cell turnover rate of the recipient to that of the donor. Indeed, UA levels of recipients correlated significantly with the baseline UA levels of the respective donors (Fig. 3).

This retrospective study has several limitations. The cell turnover in the hematopoietic system is only one of many factors contributing to serum UA levels [7,8]. UA levels are substantially influenced by the daily dietary intake, renal excretion, and concomitant medications that might influence cell turnover and renal function. As an example, a common immune suppressant, cyclosporine, which is routinely used to prevent graft-versus-host disease, can impair renal function and thus increase UA levels [8,9,10]. However, as UA levels of each patient are followed over time, confounding factors might have less influence on the overall outcome. In the current study, only patients who survived at least 1 year after HSCT were enrolled in the study. It remains unknown whether UA levels would also normalize in patients with worse outcomes.

In conclusion, HSCT is associated with significant changes in UA levels in patients with hematologic disorders.

Footnotes

Authors' Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest: No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

References

- 1.Hediger MA, Johnson RJ, Miyazaki H, Endou H. Molecular physiology of urate transport. Physiology (Bethesda) 2005;20:125–133. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00039.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kamble RT, Guo S, Ramos CA, Carrum G. Acute gout at engraftment following hematopoietic transplantation. Am J Hematol. 2011;86:961–962. doi: 10.1002/ajh.22149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamauchi T, Negoro E, Lee S, et al. A high serum uric acid level is associated with poor prognosis in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Anticancer Res. 2013;33:3947–3951. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carpenter PA, Ziegler JB, Vowels MR. Late diagnosis and correction of purine nucleoside phosphorylase deficiency with allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1996;17:121–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zegers BJ, Stoop JW, Staal GE, Wadman SK. An approach to the restoration of T cell function in a purine nucleoside phosphorylase deficient patient. Ciba Found Symp. 1978;68:231–253. doi: 10.1002/9780470720516.ch15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cannell PK, Herrmann RP. Urate metabolism during bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1992;10:337–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rieselbach RE, Bentzel CJ, Cotlove E, Frei E, 3rd, Freireich EJ. Uric acid excretion and renal function in the acute hyperuricemia of leukemia. Pathogenesis and therapy of uric acid nephropathy. Am J Med. 1964;37:872–883. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(64)90130-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shulman H, Striker G, Deeg HJ, Kennedy M, Storb R, Thomas ED. Nephrotoxicity of cyclosporin A after allogeneic marrow transplantation: glomerular thromboses and tubular injury. N Engl J Med. 1981;305:1392–1395. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198112033052306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin HY, Rocher LL, McQuillan MA, Schmaltz S, Palella TD, Fox IH. Cyclosporine-induced hyperuricemia and gout. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:287–292. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198908033210504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.da Silva JB, de Melo Lima MH, Secoli SR. Influence of cyclosporine on the occurrence of nephrotoxicity after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a systematic review. Rev Bras Hematol Hemoter. 2014;36:363–368. doi: 10.1016/j.bjhh.2014.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]