Abstract

Lung cancer etiology is multifactorial, and growing evidence has indicated that long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) are important players in lung carcinogenesis. We performed a large-scale meta-analysis of 690,564 SNPs in 15,531 autosomal lncRNAs by using datasets from six previously published genome-wide association studies (GWASs) from the Transdisciplinary Research in Cancer of the Lung (TRICL) consortium in populations of European ancestry. Previously unreported significant SNPs (P value < 1 × 10−7) were further validated in two additional independent lung cancer GWAS datasets from Harvard University and deCODE. In the final meta-analysis of all eight GWAS datasets with 17,153 cases and 239,337 controls, a novel risk SNP rs114020893 in the lncRNA NEXN-AS1 region at 1p31.1 remained statistically significant (odds ratio = 1.17; 95% confidence interval = 1.11–1.24; P = 8.31 × 10−9). In further in silico analysis, rs114020893 was predicted to change the secondary structure of the lncRNA. Our finding indicates that SNP rs114020893 of NEXN-AS1 at 1p31.1 may contribute to lung cancer susceptibility.

Lung cancer is one of the most common cancers worldwide. In the United States, it is estimated that 221,200 new lung cancer cases will occur in 20151. Despite of much devoted research effort in the treatment for lung cancer in recent decades, it remains the leading cause of cancer deaths among males worldwide and the leading cause of cancer deaths among females in more developed countries2. Although smoking has been confirmed to be the most common risk factor for lung cancer, only about one-tenth of the smokers develop lung cancer in their lifetimes3, which suggests that other factors play important roles in lung carcinogenesis4. Over the past few years, genome-wide association studies (GWASs) of lung cancer have identified multiple loci associated with lung cancer risk5,6,7,8,9,10. Several of those loci (e.g., 6p21, 5p15, 3p28 and 15q25) have been validated in multiple studies11,12. These findings have greatly advanced our knowledge of the genetic basis of lung cancer in humans.

Although much attention has been focused on the expression of protein-coding genes, accumulating evidence suggests that non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) have specialized regulatory and processing functions. For example, genetic variants of microRNAs play important roles in cancers13,14,15. To date, however, little is known about the association between genetic variation of long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) and lung cancer risk. LncRNAs are a new class of transcripts that were recently discovered, which are pervasively transcribed in the genome and critical regulators of the epigenome16. Emerging studies have demonstrated the major biological roles of lncRNAs in a variety of processes that have an impact on carcinogenesis, embryonic development, or metabolism17. Recently, SNPs in several lncRNA genes previously identified to be involved in cancer development have been reported to be associated with cancer risk, e.g. rs7763881 in the hepatocellular cancer-related HULC gene18 and rs920778 in the gastric cancer-related HOTAIR gene19. These results provide some evidence for the important roles of lncRNA SNPs in carcinogenesis.

Currently, little is known about the associations between genetic variants of lncRNAs and lung cancer risk. In the present study, we re-visited several published GWASs and evaluated the effects of lncRNA SNPs on lung cancer risk by using a large-scale meta-analysis of six previously published lung cancer GWAS datasets from the Transdisciplinary Research in Cancer of the Lung (TRICL) consortium and two additional GWAS datasets of independent Caucasian populations from Harvard University and Icelandic lung cancer study8.

Results

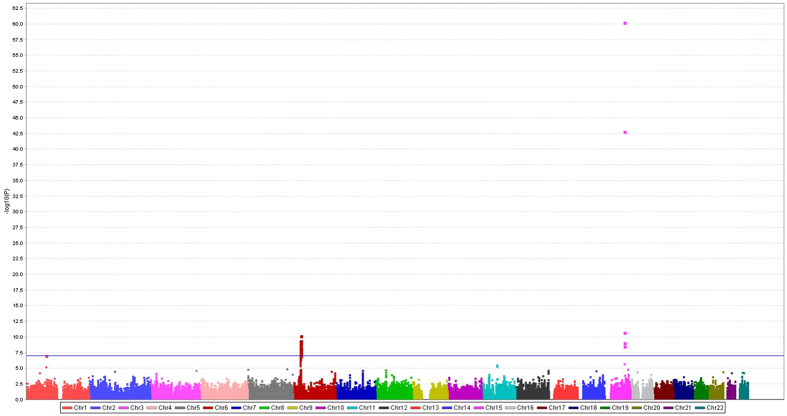

The combined dataset of six previously published GWAS datasets used for the initial analysis (discovery) consisted of 12,160 cases and 16,838 controls of European ancestry. The initially identified associations between SNPs in lncRNAs and lung cancer risk are shown in Fig. 1. In brief, the meta-analysis of 690,564 SNPs in lncRNAs from the TRICL consortium showed that 59 SNPs were associated with lung cancer risk with a P value < 1 × 10−7, and no heterogeneity among these GWAS datasets was noted, except for one SNP of rs35031105 (Supplementary Table 1). Of these 59 SNPs, 53 from 11 lncRNAs were located at the lung cancer risk-related loci 6p21.33 and 6p22.1 that have been reported previously6,20. The other five SNPs from three lncRNAs were located in 15q25.1 that was also reported by multiple studies5,10,21. Therefore, we focused on the remaining previously unreported SNP rs114020893 located in lncRNA NEXN-AS1 (also known as C1orf118) on chromosome 1p31.1 for the further analysis.

Figure 1. Manhattan plot of associations between SNPs of the lncRNA genes and risk of lung cancer.

There were 59 SNPs with a P < 1 × 10−7.

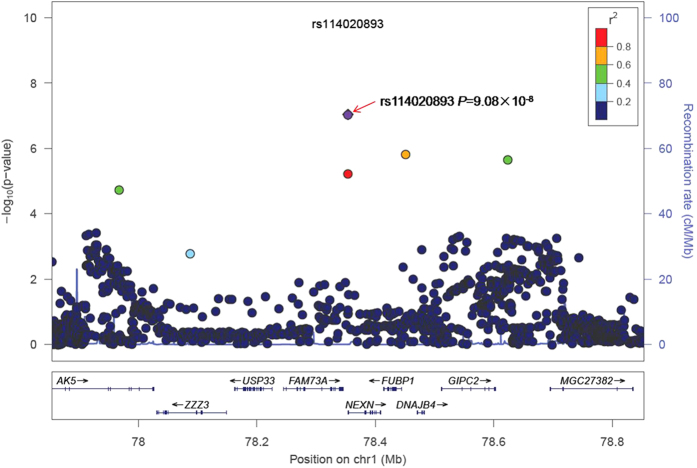

For the purposes of illustration, the forest plot of the meta-analysis of rs114020893 using the six GWAS datasets is presented in Supplementary Figure 1. For the rs114020893 C variant allele in the GWAS datasets from the Institute of Cancer Research (ICR), the MD Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC), the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the Samuel Lunenfeld Research Institute study (Toronto), and the German Lung Cancer Study (GLC)21, the allele frequencies were 0.098, 0.092, 0.072, 0.084, 0.073 and 0.066, respectively; the additive odds ratio (OR) were 1.20, 1.42, 1.41, 1.18, 1.28 and 1.11, respectively; and its risk effect was significant in the first four datasets with a larger number of observations. There was no heterogeneity observed among these datasets, with I2 of 0 and the Q-test P value of 0.672 in the meta-analysis. In the combined results, the per-unit increase of the C allele was associated with1.23-fold increase of lung cancer risk [95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.14−1.33, P = 9.08 × 10−8]. The regional association plot generated by using LocusZoom22 for rs114020893 ± 500 KB in the additive genetic model (Fig. 2) indicated that there were five other SNPs that showed moderate linkage disequilibrium (LD) with rs114020893.

Figure 2. Regional association plot of rs114020893.

The left-hand Y-axis shows the P-value of individual SNPs, which is plotted as −log10(P) against chromosomal base-pair position.The right-hand Y-axis shows the recombination rate estimated from the HapMap CEU population.

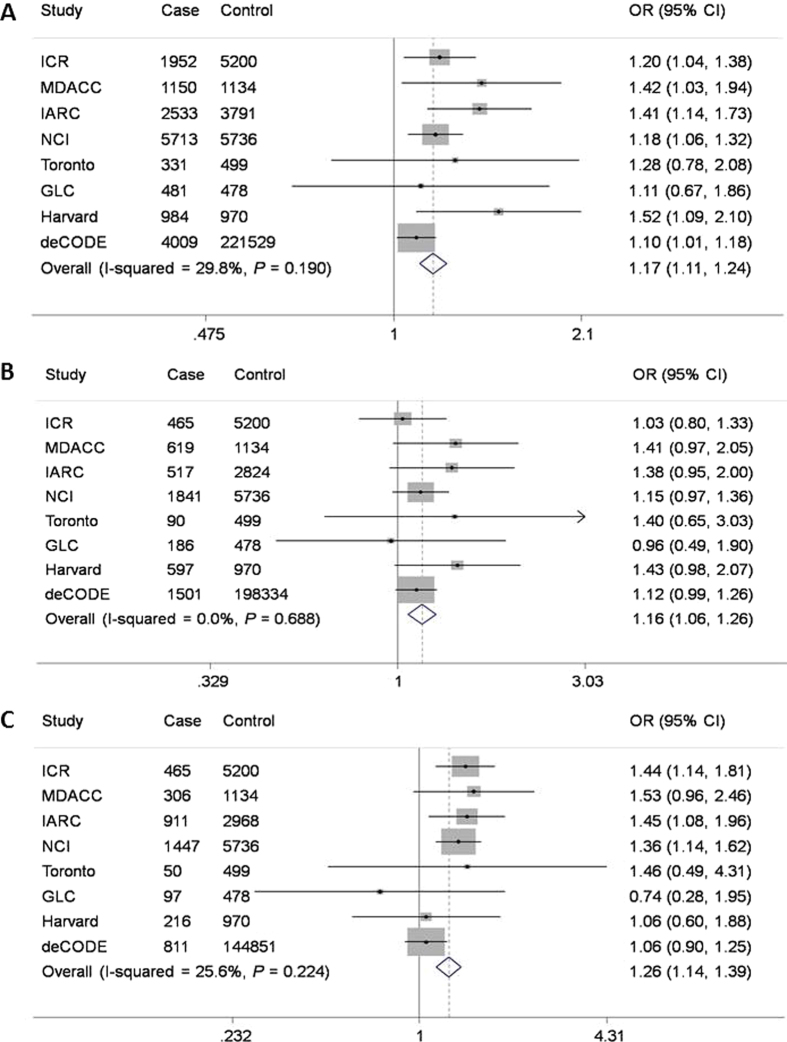

We validated this initial finding by the data for the NEXN-AS1 SNP rs114020893 from two additional independent lung cancer GWASs of Harvard University (984 cases and 970 controls) and deCODE (4,009 cases and 221,529 controls). As shown in Table 1, the rs114020893 SNP from both the Harvard and deCODE datasets was also significantly associated with risk of lung cancer (OR = 1.52, 95%CI = 1.10–2.11, P = 0.012 for Harvard and OR = 1.10, 95% CI = 1.01–1.18, P = 0.023 for deCODE), which were consistent with those derived from the six TRICL GWAS datasets. After pooling the data from all eight GWAS datasets, the rs114020893C allele was associated with a 1.17-fold (95% CI = 1.11–1.24) increased lung cancer risk, with a P value of 8.31 × 10−9, which remained statistically significant even after a conservative Bonferroni correction for 675,953 tests (Bonferroni-corrected significance cut-off: 7.24 × 10−8 from 0.05/690,564). Further subgroup analyses by tumor histology (Fig. 3) indicated that there was no difference in the association of rs114020893 with lung cancer risk between adenocarcinoma (OR = 1.16, 95% CI = 1.06–1.26) and squamous cell carcinoma (OR = 1.26, 95% CI = 1.14–1.39). The reason for this SNP not to be previously reported is because it is an imputed SNP in all the eight GWAS datasets, which suggests that other untyped SNPs could also have been missed by the published GWASs.

Table 1. Summary of the association results of rs114020893 in the eight lung cancer GWASs.

| Study population | Sample size |

rs114020893 (C) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | Controls | OR (95%CI) | P | |

| TRICL combined1 | 12160 | 16838 | 1.23 (1.14−1.33) | 9.08E-08 |

| ICR2 | 1952 | 5200 | 1.20 (1.04−1.38) | 1.13E-02 |

| MDACC3 | 1150 | 1134 | 1.42 (1.03−1.94) | 3.00E-02 |

| IARC4 | 2533 | 3791 | 1.41 (1.14−1.73) | 1.16E-03 |

| NCI5 | 5713 | 5736 | 1.18 (1.06−1.32) | 2.80E-03 |

| Toronto6 | 331 | 499 | 1.28 (0.78−2.08) | 3.28E-01 |

| GLC7 | 481 | 478 | 1.11 (0.67−1.86) | 6.77E-01 |

| Replicationcombined1 | 4993 | 222499 | 1.11 (1.03−1.20) | 5.17E-03 |

| Harvard8 | 984 | 970 | 1.52 (1.10−2.11) | 1.23E-02 |

| deCODE9 | 4009 | 221529 | 1.10 (1.01−1.18) | 2.29E-02 |

| All combined1 | 17153 | 239337 | 1.17 (1.11−1.24) | 8.31E-09 |

1The combined OR and P value were estimated using a fixed-effects model;

2ICR: the Institute of Cancer Research Genome-wide Association Study, UK;

3MDACC: The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Genome-wide Association Study, US;

4IARC: the International Agency for Research on Cancer Genome-wide Association Study, France;

5NCI: the National Cancer Institute Genome-wide Association Study, US;

6Toronto: the Samuel Lunenfeld Research Institute Genome-wide Association Study, Toronto, Canada;

7GLC: German Lung Cancer Study, Germany;

8Harvard: Harvard Lung Cancer Study, US;

9deCODE: Icelandic Lung Cancer Study, Iceland.

Figure 3.

Forest plot of the C allele effect of rs114020893 in all cases (Panel A), adenocarcinoma (Panel B) and squamous cell carcinoma (Panel C) from the eight GWASs [the Institute of Cancer Research (ICR) GWAS, the MD Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC) GWAS, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) GWAS, the National Cancer Institute (NCI) GWAS, the Samuel Lunenfeld Research Institute study (Toronto) GWAS, German Lung Cancer Study (GLC), Harvard lung cancer study (Harvard) and Icelandic Lung Cancer Study (deCODE)].

Considering the fact that rs114020893 is located within the lncRNA of NEXN-AS1, it is biologically plausible that rs114020893 may influence the function of NEXN-AS1 by affecting its folding structure. Using the online tool RNAfold (http://rna.tbi.univie.ac.at/cgi-bin/RNAfold.cgi), it was predicted that rs114020893 could cause a change in the local lncRNA structure of NEXN-AS1 as shown in Supplementary Figure 2, in which the SNP rs114020893 changes the folding structure of the NEXN-AS1.To determine in which tissues RNA transcripts (including NEXN-AS1) that include the SNP rs114020893 may be expressed, we utilized data from the ENCODE project, which systematically maps functional elements in the genome across a range of cell types23. Specifically, we scanned each RNA-seq experiment available at the ENCODE portal (http://www.encodeproject.org/) for which a GTF (Gene Transfer Format) file indicates that the transcribed regions in the human genome (build 37) were available as of June 23, 2015. From 1,011 such experiments, 156 had evidence for a gene in which rs114020893 is part of the expressed RNA. When we sorted these samples by gene abundance (either RPKM or FPKM), we observed that the highest levels of expression for genes that include this SNP were from two experiments on lung fibroblast tissue (experiments ENCSR000COO and ENCSR000CPM). This suggests that rs114020893 may alter a noncoding RNA that is expressed in lung fibroblasts, opening the door to testable mechanistic hypotheses.

Discussion

Several loci including 5p15.33, 6p21.33 and 15q25.1 have been found to be associated with lung cancer risk in previously published GWASs5,6,9,24. However, these findings could only explain a small fraction of the risk of lung cancer. In the present study with an initial meta-analysis of six previously published GWAS datasets of the TRICL consortium, we systematically evaluated the associations of genetic variants within all lncRNAs that had been reported to date17, and we further validated the most promising association in two additional independent GWAS datasets of Harvard and deCODE lung cancer studies. As a result, we found that a novel SNP rs114020893 in the lncRNA gene NEXN-AS1 located at 1p31.1 was significantly associated with lung cancer risk. This novel SNP was predicted to change the lncRNA structure. These findings suggest that genetic variation in the lncRNA regions may contribute to lung cancer etiology.

LncRNAs are often tissue-specific mRNA-like transcripts lacking significant open reading frames16. In various human tissues, lncRNAs are associated with development of diseases in a stage-specific manner, and functional lncRNAs may play a role in the development of cancer25. Emerging evidence suggests that differences in lncRNA expression levels are associated with the development of various types of cancer. For example, one notable lncRNA was discovered in the screening of genes associated with lung adenocarcinoma and was named metastasis-associated in lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1 (MALAT1)26. Additional studies found that MALAT1 could regulate gene expression, especially for those that are involved in lung cancer cell migration, metastasis, and colony formation27. Furthermore, over expression of lncRNA HOTAIR in NSCLC tumors was found to be associated with advanced stages and shorter disease-free survival, and forced expression of HOTAIR induced cell migration and anchorage-independent-cell growth in vitro28. Expression changes in three additional lncRNAs have also been linked to lung cancer risk, including smoke and cancer-associated lncRNA-1 (SCAL1), GAS6-antisense 1, and maternally expressed gene 3 (MEG3)29,30,31. These lines of evidence suggest a crucial role of lncRNAs in lung carcinogenesis.

Several GWASs have been conducted to identify genetic susceptibility loci for lung cancer5,6. Subsequent bioinformatics analysis has also revealed several lncRNAs mapped to cancer-related genetic susceptibility loci32. In the present study, we found that lung cancer risk-related loci (6p21 and 15q25) were also enriched in lncRNAs, such as RP11-650L12.2, HCP5, XXbac-BPG27H4.8, and HCG17. In this GWAS re-analysis study, we aimed to demonstrate the possibility that genetic variants in lncRNA regions might be associated with lung cancer development. This method of using non-coding regions should be complementary to the protein-coding-related approaches, such as the gene-based and pathway-based analyses33,34.

By systematically analyzing SNPs in lncRNAs, we identified a novel lung cancer risk locus (1p31.1), which harbors a potentially functional SNP rs114020893 in lncRNA NEXN-AS1. This region has also been implicated in GWASs of two diseases: Crohn’s disease35 and class II obesity31. To date, however, the potential biological mechanism underlying these findings remains unknown. Because rs114020893 is located on the exon of the NEXN-AS1 gene, the in-silico analyses predicted the influence of the T/C alleles of rs114020893 on the secondary structure of NEXN-AS1. As a result, the secondary structure was remarkably changed with the rs114020893 T > C change, indicating that this SNP may be involved in lung cancer development through alteration of the NEXN-AS1 structure and stability, resulting in the functional alteration of its interacting partners. Further studies on additional SNPs and the biological mechanisms of the NEXN-AS1 gene are warranted.

To our knowledge, this is the first study investigating the role of genetic variants of lncRNAs in lung cancer susceptibility at the whole-genome level, although the roles of lncRNAs in carcinogenesis of some other cancers have been reported. Our observation may provide a novel insight into the roles of lncRNAs in lung cancer etiology. The large sample size, ensuring sufficient statistical power to detect small effect size, is the other strength of the present study. However, there are some limitations that need to be mentioned. Firstly, our list of lncRNAs may not be comprehensive, because we were limited by those that have already been identified to date and those included in the GENCODE database (15,531 autosomal lncRNAs). Secondly, the classification of lncRNAs has not been functionally characterized, and thus little is known about the biological meanings of lncRNAs, which makes explanation of our results difficult. Thirdly, the identified novel SNP was imputed, and thus its real effect size may need to be validated in actual genotyping data in the future. Finally, it is still unclear how such a SNP modifies the formation or effects of lncRNAs. This SNP is also located at the 345 bp upstream of the NEXN gene, but its functional relevance is still not clear. It is possible that the SNP may function through the lncRNA NEXN-AS1 or play a regulatory role of the encoding gene NEXN. Further functional analysis of the variant is warranted.

In conclusion, based on the results from a large meta-analysis of eight published GWASs of European descent, we have identified a novel SNP rs114020893 T > C, located in the lncRNA NEXN-AS1 gene that is significantly associated with an increased risk of lung cancer. To confirm the biological significance of our finding, further functional analysis of the variant is warranted.

Materials and Methods

Study populations

The meta-analysis first used the combined genotyping and imputation dataset of six previously published GWASs of lung cancer with 12,160 lung cancer cases and 16,838 controls of European ancestry from the TRICL consortium and International Lung Cancer Consortium8,21,24. As shown in Supplementary Table 2, these six published studies included the Institute of Cancer Research (ICR) GWAS, the MD Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC) GWAS, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) GWAS, the National Cancer Institute (NCI) GWAS, the Samuel Lunenfeld Research Institute study (Toronto) GWAS, and the German Lung Cancer Study (GLC)21. Additional two datasets of independent GWASs of Caucasian populations was used: the Harvard Lung Cancer Study (Harvard) which includes 984 cases and 970 controls and the Icelandic Lung Cancer Study (deCODE), which, in addition to using data from chip typed individuals, also allows inclusion of individuals that have not been chip typed, but for which genotype probabilities are imputed using methods of familial imputation. The effective sample size of deCODE’s dataset is 6,612cases and 6,612 controls8 (Supplementary Table 2). A written informed consent was obtained from each participant of these GWASs, and the present study followed the study protocols approved by the institutional review board for each of the participating institutions.

Selection of lncRNA genes and SNPs

We selected 15,900 lncRNAs from the publically available database GENCODE Release22 (GRCh38; released in March, 2015)16,36. All genotyping was performed by one of Illumina HumanHap 317, 317 + 240S, 370Duo, 550, 610 or 1 M arrays8,21. The genotyping data were also used for imputation from all scans for over 10 million SNPs from the 1000 Genomes Project (phase I integrated release 3, March 2012) as the reference by using IMPUTE2 v2.1.1, MaCH v1.0 or minimac (version 2012.10.3) software. The quality control process has been detailed in previous reports8,21. As a result, the final dataset included 15,531 lncRNA genes located on autosomes, and 690,564 genotyped or imputed common [minor allele frequency (MAF) > 0.05] SNPs within these lncRNA genes were used for association analyses. SNPs with a P value < 1 × 10−7 in the TRICL datasets were further tested in the Harvard and deCODE datasets, excluding those SNPs located in the regions that had been reported to contribute to lung cancer risk in previously published studies5,6,9,24. The detailed work-flow is shown in Supplementary Figure 3.

Functional validation

We used the online tool RNAfold (http://rna.tbi.univie.ac.at/cgi-bin/RNAfold.cgi) to predict the effects of identified SNPs on the change of lncRNA. We also scanned the data from RNA-seq experiments available at the Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE) portal (http://www.encodeproject.org/) to determine in which tissues RNA transcripts (including NEXN-AS1) that include the identified SNPs may be expressed23.

Statistical methods

The statistical methods have been detailed in a previous publication8. Briefly, the association between each SNP and lung cancer risk was assessed by an additive genetic model of the minor allele, using R (v2.6), Stata v1.0 (Stata College, Texas, US), SAS software (version 9.3; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and Plink (v1.06) software. Specifically, poorly imputed SNPs defined by an information score <0.40 with IMPUTE2 or an r-square <0.30 with MaCH were excluded from the analyses. The I2 statistic to quantify the proportion of the total variation due to the heterogeneity and the Chi-square-based Cohran’s Q statistic to test for heterogeneity were calculated37. Fixed-effects models were applied when there was no heterogeneity among studies (P > 0.100 and I2 < 50%); otherwise, random-effects models were applied. The full sequences of NEXN-AS1 (NCBI Reference Sequence: NR_103535.1) containing T or C alleles in rs114020893 were used to predict the folding structures of NEXN-AS1 in RNAfold (http://rna.tbi.univie.ac.at/cgi-bin/RNAfold.cgi)38. ORs and their 95% CI were used to estimate cancer risk associated with the variant allele or genotypes.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Yuan, H. et al. A Novel Genetic Variant in Long Non-coding RNA Gene NEXN-AS1 is Associated with Risk of Lung Cancer. Sci. Rep. 6, 34234; doi: 10.1038/srep34234 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

TRICL: This work was supported by the Transdisciplinary Research in Cancer of the Lung (TRICL) Study, U19-CA148127 on behalf of the Genetic Associations and Mechanisms in Oncology (GAME-ON) Network. The Toronto study was supported by Canadian Cancer Society Research Institute(020214), Ontario Institute of Cancer and Cancer Care Ontario Chair Award to RH The ICR study was supported by Cancer Research UK (C1298/A8780 andC1298/A8362—Bobby Moore Fund for Cancer Research UK) and NCRN, HEAL and Sanofi-Aventis. Additional funding was obtained from NIH grants (5R01CA055769, 5R01CA127219, 5R01CA133996, and 5R01CA121197). The Liverpool Lung Project (LLP) was supported by The Roy Castle Lung Cancer Foundation, UK. The ICR and LLP studies made use of genotyping data from the Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium 2 (WTCCC2); a full list of the investigators who contributed to the generation of the data is available from www.wtccc.org.uk. Sample collection for the Heidelberg lung cancer study was in part supported by a grant (70–2919) from the Deutsche Krebshilfe. The work was additionally supported by a Helmholtz-DAAD fellowship (A/07/97379 to MNT) and by the NIH (U19CA148127). The KORA Surveys were financed by the GSF, which is funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education, Science, Research and Technology and the State of Bavaria. The Lung Cancer in the Young study (LUCY) was funded in part by the National Genome Research Network (NGFN), the DFG (BI576/2-1; BI 576/2-2), the Helmholtzgemeinschaft (HGF) and the Federal office for Radiation Protection (BfS: STSch4454). Genotyping was performed in the Genome Analysis Center (GAC) of the Helmholtz Zentrum Muenchen. Support for the Central Europe, HUNT2/Tromsø and CARET genome-wide studies was provided by Institut National du Cancer, France. Support for the HUNT2/Tromsø genome-wide study was also provided by the European Community (Integrated Project DNA repair, LSHG-CT- 2005–512113), the Norwegian Cancer Association and the Functional Genomics Programme of Research Council of Norway. Support for the Central Europe study, Czech Republic, was also provided by the European Regional Development Fund and the State Budget of the Czech Republic (RECAMO, CZ.1.05/2.1.00/03.0101). Support for the CARET genome-wide study was also provided by grants from the US National Cancer Institute, NIH (R01 CA111703 and UO1 CA63673), and by funds from the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center. Additional funding for study coordination, genotyping of replication studies and statistical analysis was provided by the US National Cancer Institute (R01 CA092039). The lung cancer GWAS from Estonia was partly supported by a FP7 grant (REGPOT245536), by the Estonian Government (SF0180142s08), by EU RDF in the frame of Centre of Excellence in Genomics and Estoinian Research Infrastructure’s Roadmap and by University of Tartu (SP1GVARENG). The work reported in this paper was partly undertaken during the tenure of a Postdoctoral Fellowship from the IARC (for MNT). The Environment and Genetics in Lung Cancer Etiology (EAGLE), the Alpha-Tocopherol, Beta-Carotene Cancer Prevention Study (ATBC), and the Prostate, Lung, Colon, Ovary Screening Trial (PLCO) studies and the genotyping of ATBC, the Cancer Prevention Study II Nutrition Cohort (CPS-II) and part of PLCO were supported by the Intramural Research Program of NIH, NCI, Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics. ATBC was also supported by US Public Health Service contracts (N01-CN-45165, N01-RC-45035 and N01-RC-37004) from the NCI. PLCO was also supported by individual contracts from the NCI to the University of Colorado Denver (NO1-CN-25514), Georgetown University (NO1-CN-25522), Pacific Health Research Institute (NO1-CN-25515), Henry Ford Health System (NO1-CN-25512), University of Minnesota(NO1-CN-25513), Washington University(NO1-CN-25516), University of Pittsburgh (NO1-CN-25511), University of Utah (NO1-CN-25524), Marshfield Clinic Research Foundation (NO1-CN-25518), University of Alabama at Birmingham (NO1-CN-75022, Westat, Inc. NO1-CN-25476), University of California, Los Angeles (NO1-CN-25404). The Cancer Prevention Study II Nutrition Cohort was supported by the American Cancer Society. The NIH Genes, Environment and Health Initiative (GEI) partly funded DNA extraction and statistical analyses (HG-06-033-NCI-01 andRO1HL091172-01), genotyping at the Johns Hopkins University Center for Inherited Disease Research (U01HG004438 and NIH HHSN268200782096C) and study coordination at the GENEVA Coordination Center (U01 HG004446) for EAGLE and part of PLCO studies. Funding for the MD Anderson Cancer Study was provided by NIH grants (P50 CA70907, R01CA121197, R01CA127219, U19 CA148127, R01 CA55769, K07CA160753) and CPRIT grant (RP100443). Genotyping services were provided by the Center for Inherited Disease Research (CIDR). CIDR is funded through a federal contract from the NIH to The Johns Hopkins University (HHSN268200782096C). The Harvard Lung Cancer Study was supported by the NIH (National Cancer Institute) grants CA092824, CA090578, and CA074386. deCODE: The project was funded in part by GENADDICT: LSHMCT-2004-005166), the National Institutes of Health (R01-DA017932). As Duke Cancer Institute members, Q.W. and K.O. acknowledge support from the Duke Cancer Institute as part of the P30 Cancer Center Support Grant (Grant ID: NIH CA014236). Q.W. was also supported by a start-up fund from Duke Cancer Institute, Duke University Medical Center. Hua Yuan was sponsored by Collaborative Innovation Center for Cancer Personalized Medicine, Nanjing Medical University. We also acknowledge support from U01 HG007033 (to R.J.K.) and LUNGevity Foundation (to Z.H.G.).

Footnotes

Author Contributions H.Y. and Q.W. designed and conceived the experiments. H.L., Z.L. and K.O. helped to analyze the data. Y.H., L.S., Y.W., R.J.H., J.M., Y.B., P.B., H.B., A.R., R.S.H., N.C., M.T.L., J.H., A.R., D.C.C., Z.H.G., R.J.K. and C.I. Amos collected the samples and provided data. All authors reviewed the paper.

References

- Siegel R. L., Miller K. D. & Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin 65, 5–29, doi: 10.3322/caac.21254 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torre L. A. et al. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin, doi: 10.3322/caac.21262 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doll R. & Peto R. The causes of cancer: quantitative estimates of avoidable risks of cancer in the United States today. J Natl Cancer Inst 66, 1191–1308 (1981). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cote M. L. et al. Increased risk of lung cancer in individuals with a family history of the disease: a pooled analysis from the International Lung Cancer Consortium. Eur J Cancer 48, 1957–1968, doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.01.038 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amos C. I. et al. Genome-wide association scan of tag SNPs identifies a susceptibility locus for lung cancer at 15q25.1. Nat Genet 40, 616–622, doi: 10.1038/ng.109 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. et al. Common 5p15.33 and 6p21.33 variants influence lung cancer risk. Nat Genet 40, 1407–1409, doi: 10.1038/ng.273 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landi M. T. et al. A genome-wide association study of lung cancer identifies a region of chromosome 5p15 associated with risk for adenocarcinoma. Am J Hum Genet 85, 679–691, doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.09.012 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. et al. Rare variants of large effect in BRCA2 and CHEK2 affect risk of lung cancer. Nat Genet 46, 736–741, doi: 10.1038/ng.3002 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung R. J. et al. A susceptibility locus for lung cancer maps to nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit genes on 15q25. Nature 452, 633–637, doi: 10.1038/nature06885 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorgeirsson T. E. et al. A variant associated with nicotine dependence, lung cancer and peripheral arterial disease. Nature 452, 638–642, doi: 10.1038/nature06846 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welter D. et al. The NHGRI GWAS Catalog, a curated resource of SNP-trait associations. Nucleic Acids Res 42, D1001–D1006, doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1229 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truong T. et al. Replication of lung cancer susceptibility loci at chromosomes 15q25, 5p15, and 6p21: a pooled analysis from the International Lung Cancer Consortium. J Natl Cancer Inst 102, 959–971, doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq178 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seven M., Karatas O. F., Duz M. B. & Ozen M. The role of miRNAs in cancer: from pathogenesis to therapeutic implications. Future Oncol 10, 1027–1048, doi: 10.2217/fon.13.259 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guz M. et al. MicroRNAs-role in lung cancer. Dis Markers 2014, 218169, doi: 10.1155/2014/218169 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava K. & Srivastava A. Comprehensive review of genetic association studies and meta-analyses on miRNA polymorphisms and cancer risk. PLoS One 7, e50966, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050966 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derrien T. et al. The GENCODE v7 catalog of human long noncoding RNAs: analysis of their gene structure, evolution, and expression. Genome Res 22, 1775–1789, doi: 10.1101/gr.132159.111 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haemmerle M. & Gutschner T. Long Non-Coding RNAs in Cancer and Development: Where Do We Go from Here? Int J Mol Sci 16, 1395–1405, doi: 10.3390/ijms16011395 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y. et al. A genetic variant in long non-coding RNA HULC contributes to risk of HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma in a Chinese population. PLoS One 7, e35145, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035145 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan W. et al. A functional lncRNA HOTAIR genetic variant contributes to gastric cancer susceptibility. Mol Carcinog, doi: 10.1002/mc.22261 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xun W. W. et al. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms (5p15.33, 15q25.1, 6p22.1, 6q27 and 7p15.3) and lung cancer survival in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC). Mutagenesis 26, 657–666, doi: 10.1093/mutage/ger030 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timofeeva M. N. et al. Influence of common genetic variation on lung cancer risk: meta-analysis of 14 900 cases and 29 485 controls. Hum Mol Genet 21, 4980–4995, doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds334 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruim R. J. et al. LocusZoom: regional visualization of genome-wide association scan results. Bioinformatics 26, 2336–2337, doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq419 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consortium E. P. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature 489, 57–74, doi: 10.1038/nature11247 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay J. D. et al. Lung cancer susceptibility locus at 5p15.33. Nat Genet 40, 1404–1406, doi: 10.1038/ng.254 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauptman N. & Glavac D. Long non-coding RNA in cancer. Int J Mol Sci 14, 4655–4669, doi: 10.3390/ijms14034655 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard D. et al. A long nuclear-retained non-coding RNA regulates synaptogenesis by modulating gene expression. Embo Journal 29, 3082–3093, doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.199 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutschner T. et al. The Noncoding RNA MALAT1 Is a Critical Regulator of the Metastasis Phenotype of Lung Cancer Cells. Cancer Research 73, 1180–1189, doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-12-2850 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa T. et al. Large noncoding RNA HOTAIR enhances aggressive biological behavior and is associated with short disease-free survival in human non-small cell lung cancer. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 436, 319–324, doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.05.101 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thai P. et al. Characterization of a Novel Long Noncoding RNA, SCAL1, Induced by Cigarette Smoke and Elevated in Lung Cancer Cell Lines. American Journal of Respiratory Cell and Molecular Biology 49, 204–211, doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2013-0159RC (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han L. et al. Low expression of long noncoding RNA GAS6-AS1 predicts a poor prognosis in patients with NSCLC. Medical Oncology 30, doi: Unsp 694Doi 10.1007/S12032-013-0694-5 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berndt S. I. et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies 11 new loci for anthropometric traits and provides insights into genetic architecture. Nature Genetics 45, 501–U569, doi: 10.1038/Ng.2606 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin G. F. et al. Human polymorphisms at long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) and association with prostate cancer risk. Carcinogenesis 32, 1655–1659, doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr187 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei S. et al. Association of a novel functional promoter variant (rs2075533 C > T) in the apoptosis gene TNFSF8 with risk of lung cancer–a finding from Texas lung cancer genome-wide association study. Carcinogenesis 32, 507–515, doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr014 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H. et al. An analysis of single nucleotide polymorphisms of 125 DNA repair genes in the Texas genome-wide association study of lung cancer with a replication for the XRCC4 SNPs. DNA Repair (Amst) 10, 398–407, doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2011.01.005 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jostins L. et al. Host-microbe interactions have shaped the genetic architecture of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature 491, 119–124, doi: 10.1038/Nature11582 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrow J. et al. GENCODE: producing a reference annotation for ENCODE. Genome Biol 7 Suppl 1, S4 1-9, doi: 10.1186/gb-2006-7-s1-s4 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penegar S. et al. National study of colorectal cancer genetics. Br J Cancer 97, 1305–1309, doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603997 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber A. R., Lorenz R., Bernhart S. H., Neubock R. & Hofacker I. L. The Vienna RNA websuite. Nucleic Acids Res 36, W70–W74, doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn188 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.