Abstract

PBOND is a web server that predicts the conformation of the peptide bond between any two amino acids. PBOND classifies the peptide bonds into one out of four classes, namely cis imide (cis-Pro), cis amide (cis-nonPro), trans imide (trans-Pro) and trans amide (trans-nonPro). Moreover, for every prediction a reliability index is computed. The underlying structure of the server consists of three stages: (1) feature extraction, (2) feature selection and (3) peptide bond classification. PBOND can handle both single sequences as well as multiple sequences for batch processing. The predictions can either be directly downloaded from the web site or returned via e-mail. The PBOND web server is freely available at http://195.251.198.21/pbond.html.

Key words: peptide bond, cis/trans isomerization, support vector machine

Introduction

The peptide bond linking adjacent amino acids in protein structures can adopt either the cis or the trans conformation. The cis conformation occurs rarely in polypeptides because of the higher intrinsic energy compared to the trans conformation. Despite their infrequent occurrence, cis peptide bonds are very important in a variety of biological processes, such as protein folding, regulation, cell signaling and splicing of protein molecules (1). Recent studies have indicated that prolyl cis/trans isomerization can act as a molecular timer to help control the cellular process, making it a new target for therapeutic interventions (2). Furthermore, cis peptide bonds, especially the ones between non-proline residues, are located near the active sites of proteins, or have roles in the function of the protein molecules 1., 3..

In order to predict the proline isomerization, FrÖmmel et al. (4) extracted patterns based on physicochemical properties. Wang et al. (5) trained a support vector machine (SVM) using only the primary sequence as input in order to discriminate between the two conformations of proline peptide bonds. Song et al. (6) predicted the isomerization of proline peptide bonds using multiple sequence alignment profiles and secondary structure as input. The COPS algorithm (7) aimed to predict the peptide bond formation between any two amino acids employing an extension of the Chou-Fasman parameters.

Most of the aforementioned studies focus only on the proline residues, ignoring the rare but highly important non-proline cis peptide bonds. Here, we make a further distinction of the peptide bonds into four classes, namely cis imide (cis-Pro), cis amide (cis-nonPro), trans imide (trans-Pro) and trans amide (trans-nonPro), by developing the PBOND web server. Hence, PBOND not only predicts the peptide bond conformation between any two amino acids, but also designates potential cis-nonPro formations. Furthermore, a reliability index is computed, which represents the confidence assigned to each prediction. A majority voting scheme is also available, which provides consensus prediction of 10 SVM classifiers. PBOND has been developed using 3,050 high-quality protein sequences with resolution <2.0Å, R-factor <0.25 and sequence identity <25%.

Method

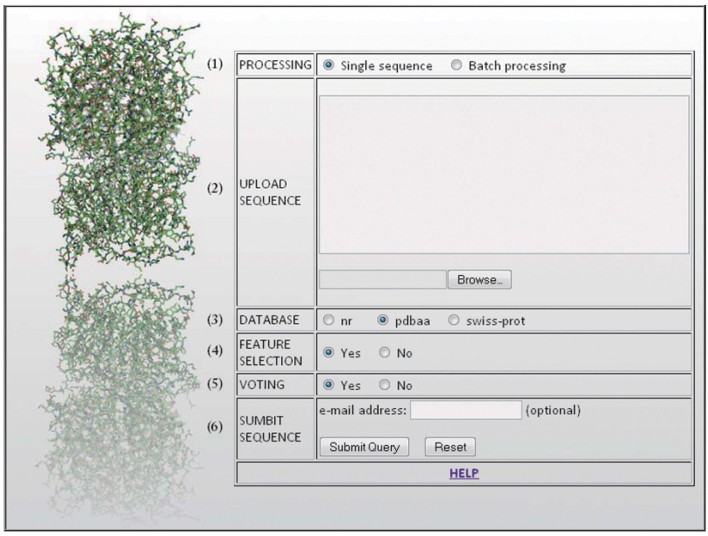

The PBOND web server graphical interface, as shown in Figure 1, consists of six fields. The numbers placed next to every field in the figure follow the same notation as below.

Figure 1.

The PBOND web server graphical interface.

1. Processing: The user may choose to process either a single sequence or upload multiple sequences for batch processing; there is no upper limit to the number of sequences submitted for batch processing.

2. Upload sequence: Amino acid sequences can be provided in FASTA format either by pasting them in the text box or uploading them within a text file. Each input sequence must have a maximum length of 1,000 residues.

3. Database: After uploading the sequence(s), several features are extracted. More specifically, multiple sequence alignment profiles, in the form of position-specific scoring matrices (PSSMs), are obtained after running PSI-BLAST (8) against one of the provided protein databases; the choice of the database highly affects the computational time, whereas only slight perturbations are expected in terms of performance. Next, the predicted secondary structure of every residue in the query sequence is computed using PSIPRED (9); real valued predictions of solvent accessibility are obtained from RVP-net (10); six widely used physicochemical properties are also employed for every residue (volume, hydrophobicity, polarity, charge, aromatic and aliphatic character). All the above features are extracted using a sliding window with size w=11 7., 11., centered at each residue, whose peptide bond with the preceding amino acid we are trying to predict; outside this range, the influence of the surrounding residues towards the peptide bonds formation decreases. The resulting feature vector consists of 331 attributes.

4. Feature selection: Next, the user may choose either to employ the whole feature vector for the prediction or an optimal reduced set of features (12) identified in our previous study (11).

5. Voting: The user may choose to invoke either a single SVM model or 10 SVM models, each one trained with a different dataset. In the latter, each model independently assigns a label (cis-Pro, cis-nonPro, trans-Pro, trans-nonPro) to every residue in the query sequence and then a linear time majority voting algorithm calculates the consensus of the 10 predictions.

6. Submit sequence: If a valid e-mail address is supplied, the results are submitted in a compressed file; otherwise, if the e-mail field is left blank, the prediction results can be downloaded directly from the web page, where they will be available for 10 days.

The output of the PBOND server consists of a compressed file containing either a single text file, or multiple text files, in case of batch processing. These files contain plain text with the predictions for every sequence uploaded, along with a reliability index for every prediction. The first and last five peptide bonds of every sequence are labeled as “n/a” since there are not enough residues in the sliding window to make a prediction. It should be noted that multiple simultaneous requests can be handled efficiently by PBOND. The PBOND web server is freely available at http://195.251.198.21/pbond.html.

Evaluation

Due to the scarcity of cis peptide bonds (both cis-Pro and cis-nonPro), a severe class imbalance problem emerges, posing a tradeoff between the identification of as many potential cis formations and certain false positive predictions. However, the biological significance of cis formations outweighs possible overpredictions. Hence, special attention was given during the training and evaluation of the PBOND server so that important cis formations are not neglected. For this purpose, the predictive models of PBOND server have been trained using fully balanced datasets, in which all four classes are equally represented. The evaluation of PBOND has been performed on fully balanced disjoint data segments coming from the initial unbalanced dataset 13., 14..

Table 1 presents the performance achieved using the initial feature vector, with and without performing majority voting. Sensitivity and positive predictive value (PPV) are also provided for the two general classes (cis/trans). The performance achieved using the initial input vector is in general quite poor, even though voting slightly improves the results.

Table 1.

Performance obtained using the initial feature vector with and without majority voting

| Class | No voting |

Voting |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity (%) | PPV (%) | Sensitivity (%) | PPV (%) | |

| cis-Pro | 62.30 | 61.95 | 71.18 | 67.20 |

| cis-nonPro | 61.05 | 60.40 | 64.41 | 61.79 |

| cis | 61.68 | 61.18 | 67.78 | 64.45 |

| trans-Pro | 61.70 | 62.06 | 65.25 | 69.37 |

| trans-nonPro | 59.90 | 60.58 | 60.17 | 62.83 |

| trans | 60.80 | 61.32 | 62.71 | 66.10 |

| Overall accuracy (%) | 61.24 | 65.39 | ||

In Table 2, the performance achieved using the optimal reduced set of features is shown, with and without the employment of the majority voting algorithm. It is clear that the feature selection improves the classification outcome to a certain extent; a further increment in the results is achieved using the consensus prediction of the 10 models. Furthermore, the reliability index associated with every prediction can be used for post processing the prediction results.

Table 2.

Performance obtained using the optimal reduced set of features with and without majority voting

| Class | No voting |

Voting |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity (%) | PPV (%) | Sensitivity (%) | PPV (%) | |

| cis-Pro | 71.55 | 69.46 | 73.72 | 71.90 |

| cis-nonPro | 77.40 | 68.08 | 76.27 | 73.77 |

| cis | 74.45 | 68.77 | 75.00 | 72.84 |

| trans-Pro | 67.75 | 70.71 | 71.18 | 73.04 |

| trans-nonPro | 64.65 | 73.92 | 72.88 | 75.44 |

| trans | 66.20 | 72.32 | 72.03 | 74.24 |

| Overall accuracy (%) | 70.23 | 73.67 | ||

A detailed comparison of the available prediction methods in the literature and PBOND is presented in Table 3. Both qualitative and quantitative measures are provided. Based on the physicochemical properties of the ±6 surrounding amino acids, Frömmel et al. (4) aimed to predict the peptide bond conformation of proline residues. They extracted 6 patterns that correctly assigned 73% of cis prolines. Although the reported results are promising, such refined dataset (242 proline bonds) diminishes the credibility of the proposed method. The proposed rules were later tested on a larger dataset, yielding inferior results. Wang et al. (5) as well, focused only on the proline residues and employed single sequence information coded in binary form in order to predict the conformation of the peptide bond. The prediction accuracy achieved by this method is 70% and 77% when evaluated with independent datasets and the jackknife test, respectively. Song et al. (6) provided multiple sequence alignment profiles coupled with secondary structure information as input to an SVM in order to predict the proline cis/trans isomerization. The overall reported accuracy is 71% after performing five-fold cross validation. Only Pahlke et al. (7) aimed to predict the peptide bond conformation between any two amino acids, using the secondary structure of amino acid triplets; however, the reported results (overall accuracy 66%) are quite unsatisfactory. This could be attributed to the refined length of the sliding window, as well as to the small number of employed features. The performance of PBOND compares well with previously published studies, albeit validated on different datasets and using different evaluation methods. Moreover, PBOND is able to identify the scarce but highly important non-proline cis peptide bonds.

Table 3.

Comparison of PBOND with available peptide bond conformation prediction methods

| Method | Target | Feature | Sensitivity (%) | Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frömmel et al. (4) | Proline | Physicochemical properties | 73 | 86 |

| Wang et al. (5) | Proline | Single sequence | 77 | 77 |

| Song et al. (6) | Proline | PSSM, secondary structure | 71 | 71 |

| Pahlke et al. (7) | Any amino acid | Secondary structure | 35 | 66 |

| PBOND | Any amino acid |

PSSM, secondary structure, accessible surface area, and physicochemical properties | 75 |

74 |

| Proline | 74 | |||

| Non-Proline | 76 | |||

Authors’ contributions

KPE designed the study, implemented the server and prepared the manuscript. TPE and CP provided valuable comments and suggestions throughout the study and helped in the manuscript preparation. ANT and DIF supervised the study and provided substantial advice and guidance. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

References

- 1.Pal D., Chakrabarti P. Cis peptide bonds in proteins: residues involved, their conformations, interactions and locations. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;294:271–288. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lu K.P. Prolyl cis-trans isomerization as a molecular timer. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2007;3:619–629. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weiss M.S. Peptide bonds revisited. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1998;5:676. doi: 10.1038/1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frömmel C., Preissner R. Prediction of prolyl residues in cis-conformation in protein structures on the basis of the amino acid sequence. FEBS Lett. 1990;277:159–163. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80833-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang M.L. Support vector machines for prediction of peptidyl prolyl cis/trans isomerization. J. Pept. Res. 2004;63:23–28. doi: 10.1046/j.1399-3011.2004.00100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Song J. Prediction of cis/trans isomerization in proteins using PSI-BLAST profiles and secondary structure information. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:124. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pahlke D. COPS—cis/trans peptide bond conformation prediction of amino acids on the basis of secondary structure information. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:685–686. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Altschul S.F. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McGuffin L.J. The PSIPRED protein structure prediction server. Bioinformatics. 2000;16:404–405. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/16.4.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahmad S. RVP-net: online prediction of real valued accessible surface area of proteins from single sequences. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1849–1851. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Exarchos K.P. Prediction of cis/trans isomerization using feature selection and support vector machines. J. Biomed. Inform. 2009;42:140–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kohavi R., John G.H. Wrappers for feature subset selection. Artif. Intel. 1997;97:273–324. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tan P.N. Addison Wesley; Boston, USA: 2005. Introduction to Data Mining. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Witten I.H., Frank E. second editon. Morgan Kaufman; San Fransisco, USA: 2005. Data Mining: Practical Machine Learning Tools and Techniques. [Google Scholar]