Abstract

Genetic deletion of the tyrosine kinase JAK2 or the downstream transcription factor STAT5 in liver impairs growth hormone (GH) signalling and thereby promotes fatty liver disease. Hepatic STAT5 deficiency accelerates liver tumourigenesis in presence of high GH levels. To determine whether the upstream kinase JAK2 exerts similar functions, we crossed mice harbouring a hepatocyte-specific deletion of JAK2 (JAK2Δhep) to GH transgenic mice (GHtg) and compared them to GHtgSTAT5Δhep mice. Similar to GHtgSTAT5Δhep mice, JAK2 deficiency resulted in severe steatosis in the GHtg background. However, in contrast to STAT5 deficiency, loss of JAK2 significantly delayed liver tumourigenesis. This was attributed to: (i) activation of STAT3 in STAT5-deficient mice, which was prevented by JAK2 deficiency and (ii) increased detoxification capacity of JAK2-deficient livers, which diminished oxidative damage as compared to GHtgSTAT5Δhep mice, despite equally severe steatosis and reactive oxygen species (ROS) production. The reduced oxidative damage in JAK2-deficient livers was linked to increased expression and activity of glutathione S-transferases (GSTs). Consistent with genetic deletion of Jak2, pharmacological inhibition and siRNA-mediated knockdown of Jak2 led to significant upregulation of Gst isoforms and to reduced hepatic oxidative DNA damage. Therefore, blocking JAK2 function increases detoxifying GSTs in hepatocytes and protects against oxidative liver damage.

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is becoming the most common chronic liver disease and represents an enormous public health problem. Accumulation of ectopic lipids in liver is the hallmark of NAFLD. Its histologic spectrum ranges from simple steatosis to the progressive form of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), which might further progress to cirrhosis and its related complications, such as hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)1,2,3. There is evidence that HCC can develop in NAFLD patients even without cirrhosis, suggesting an association between abnormal metabolic processes and HCC2,4,5,6. Increased generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) is found in patients and mouse models with NAFLD6,7,8,9,10,11. When the equilibrium between ROS generation and the antioxidant defence is disrupted, the resulting oxidative stress promotes liver injury, which increases the risk for HCC development7.

Growth hormone (GH) affects whole-body physiology via the widely expressed GH receptor (GHR). In the liver GH activates the Janus kinase (JAK) 2 and signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) 5 signalling pathway to regulate target genes involved in vital liver functions12. GH-deficient or GH-resistant states both cause impaired signal transduction through the GHR in liver and this correlates with chronic liver disease including NAFLD13,14,15,16. Similarly, mice lacking components of the GHR-JAK2-STAT5 axis in hepatocytes develop hepatic GH resistance and steatosis17,18,19,20,21. We and others identified hepatic STAT5 deficiency as being associated with higher susceptibility to liver cancer20,22,23,24, driven through progressive steatosis.

Here, we addressed the impact of hepatic JAK2 deficiency on the progression of hepatic steatosis. Furthermore, we aimed to elucidate the contribution of hepatic JAK2 and STAT5 deficiency to oxidative stress with consequence for HCC development in a situation of hyperactived GH signalling. Therefore, we crossed mice harbouring a hepatocyte-specific deletion of either JAK2 or STAT5 (JAK2Δhep, STAT5Δhep; using AlfpCre24,25) to growth hormone transgenic mice (GHtg)26. GHtg mice display high systemic circulating levels of GH that are causally related to a sustained increase in hepatocyte turnover and hyperplasia followed by development of hepatocellular tumours26.

Consistent with previous findings18,21, JAK2 deficiency caused hepatic steatosis by inducing lipid redistribution to the liver and hepatic lipid synthesis. Yet, despite profound steatosis in GHtgJAK2Δhep mice, liver tumourigenesis was delayed as compared to GHtgSTAT5Δhep. While accelerated tumourigenesis in STAT5-deficient mice was associated with aberrant activation of STAT3 and increased oxidative damage, delayed carcinogenesis in JAK2-deficient mice was linked to reduced STAT3 signalling and ROS-induced oxidative damage.

Results

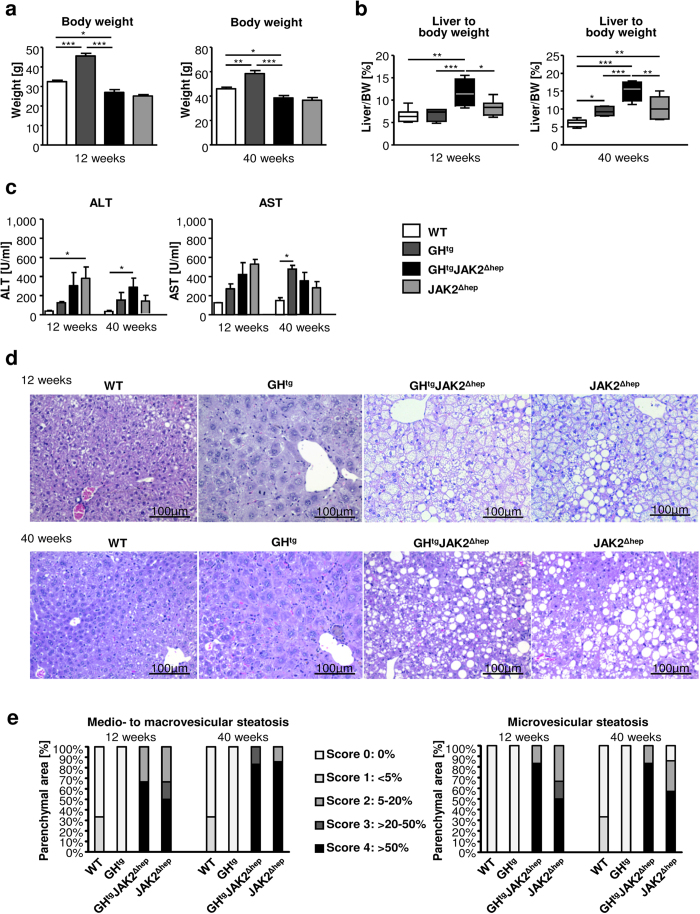

JAK2 deficiency promotes hepatic steatosis by ectopic lipid redistribution and de novo lipogenesis

JAK2 deficiency alone and in combination with hyperactivated GH signalling resulted in severe hepatic steatosis and a reduction in body weight, which is consistent with previous reports18,21. The reduction in body weight remained at approximately 20% in both JAK2-deficient lines compared to WT mice at 12 and 40 weeks of age, while body weights of GHtg mice were increased (Fig. 1a). Hepatomegaly was already evident in 12-week old GHtgJAK2Δhep animals. At 40 weeks of age, GHtgJAK2Δhep mice displayed increased liver weight (LW) to body weight (BW) ratios of 15% compared to WT mice, while LW/BW ratios of GHtg and JAK2Δhep mice were elevated by 10% (Fig. 1b). Furthermore, in comparison to WT mice, serum levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate-aminotransferase (AST) were elevated in all genotypes as indicators of liver damage (Fig. 1c). Subsequent histopathological analysis confirmed severe steatosis in both GHtgJAK2Δhep and JAK2Δhep mice characterised by medio- to macro- and microvesicular steatosis (Fig. 1d), which was accompanied by mild lobular inflammation at 40 weeks of age when compared to WT littermates (Supplementary Fig. S1a). Particularly, microvesicular steatosis was more prominent in livers of young and aged GHtgJAK2Δhep mice (Fig. 1e, Supplementary Fig. S1a). Electron microscopy analysis revealed big and swollen mitochondria in GHtgJAK2Δhep and JAK2Δhep livers (Supplementary Fig. S1b), indicating mitochondrial dysfunction and fatty degeneration in hepatocytes.

Figure 1. Loss of hepatic JAK2 leads to profound hepatic steatosis.

(a) Body weights of mice at 12 and 40 weeks of age (n ≥ 4/genotype for each time point) (b) Liver weight (LW)/body weight (BW) ratio of mutant and WT mice at indicated time points (n ≥ 4/genotype). (c) Liver damage was quantified by measuring serum levels of the liver enzymes ALT and AST at indicated time points (n ≥ 4/genotype). (d) H&E staining of liver sections at indicated time points. (e) Histopathological analysis assessing medio- and microvesicular steatosis (n ≥ 4/genotype). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001.

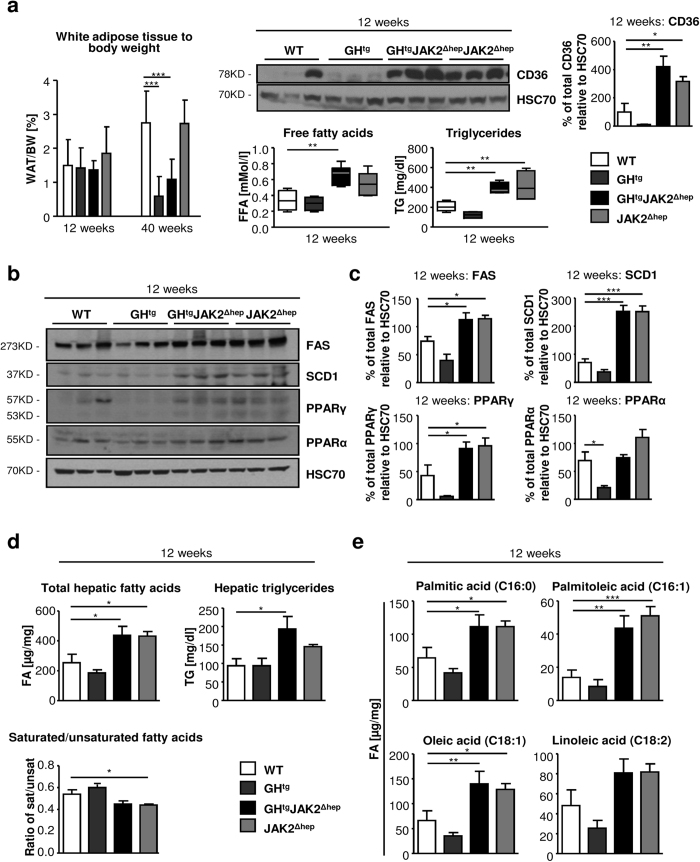

Next, we investigated the consequences of JAK2 deficiency for lipid metabolism. In GHtgJAK2Δhep animals, high GH levels led to massive lysis of perigonadal white adipose tissue (WAT), which was not affected in JAK2Δhep mice (Fig. 2a). Lipolysis was manifested by a reduction of WAT/BW ratios over time and an increase in circulating free fatty acids (FFAs). This coincided with greatly elevated protein levels of FA translocase CD36 in JAK2Δhep and GHtgJAK2Δhep livers, indicating an increased capability of hepatic FFA uptake18,27. Furthermore, significantly elevated serum triglyceride (TG) levels, were found in JAK2Δhep and GHtgJAK2Δhep mice (Fig. 2a), indicative of hypertriglyceridemia28. Hepatic steatosis observed in both JAK2-deficient lines was not only a result of ectopic FA uptake but also resulted from enhanced expression of key enzymes involved in de novo lipogenesis. Lipogenic proteins like fatty acid synthase (FAS), stearoyl-CoA desaturase (SCD) 1, and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) were significantly upregulated as verified with Western blot quantification in both JAK2-deficient lines (Fig. 2b,c). Protein levels of PPARα, a major regulator of catabolism of FAs, were not changed in JAK2-deficient livers (Fig. 2b,c). In addition, detailed profiling of steatotic livers at 12 and 40 weeks of age revealed increased total FA and TG amounts characterised by significantly elevated unsaturated FAs like palmitoleic acid and oleic acid (Fig. 2d,e; Supplementary Fig. S2a–c). Similar results have been described for GHtgSTAT5Δhep mice where profound steatosis was a result of increased WAT mobilisation and the induction of hepatic de novo lipogenesis24. Collectively, these data indicate that a combination of increased mobilisation of WAT and the induction of hepatic de novo lipogenesis contributes to the steatotic phenotype of both JAK2-deficient lines.

Figure 2. JAK2 deficiency leads to increased mobilisation of fatty acids from the periphery and hepatic de novo lipogenesis.

(a) WAT/body weight ratio of perigonadal fat tissue indicating lipid mobilisation at indicated time points (n ≥ 4/genotype). Representative Western blot analysis of whole liver homogenates and Western blot quantification of CD36 from 12-week-old animals. HSC70 is shown as loading control (n = 3/genotype). Scans of blots are presented in Supplementary Fig. S8. At 12 weeks of age, FFA serum levels, which were determined using an enzymatic test, were elevated in all mice lacking JAK2 (n ≥ 5/genotype). Serum TG levels were measured at 12 weeks of age (n ≥ 4/genotype). (b) Representative Western blot analysis of whole liver homogenates from 12-week-old animals. As a loading control HSC70 is shown (n = 3/genotype). (c) Western blot quantification of total FAS, SCD1, PPARγ and PPARα. Scans of blots are presented in Supplementary Fig. S8. (d) Hepatic total FA and TG amounts were measured at 12 weeks of age (n ≥ 6/genotype). Ratio of saturated/unsaturated hepatic FAs at 12 weeks of age (n ≥ 8/genotype). (e) Detailed profiling of steatotic livers using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) showed elevated unsaturated FAs at 12 weeks of age (n ≥ 8/genotype). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001.

Liver tumourigenesis is delayed upon loss of JAK2 in GHtg mice

High systemic levels of GH significantly reduce the life expectancy of GHtg mice24,29 which is corrected upon hepatic STAT524 or JAK2 deficiency (Fig. 3a). We and others reported that hepatic STAT5 deficiency promotes liver tumour development and progression22,23,24. At 28 weeks of age, all GHtgSTAT5Δhep animals succumbed to liver tumours, which were characterised by broadening of liver cell cords and the loss of lobular plate architecture, pronounced cellular pleomorphisms and solid or trabecular growth pattern24. In contrast, GHtg mice developed first tumours 12 weeks later with an incidence rate of 34% (Fig. 3b,c). At this time point 100% of GHtgJAK2Δhep and JAK2Δhep livers remained tumour-free (Fig. 3b,c), despite similar proliferation rates of hepatocytes (Supplementary Fig. S3a). The occurrence of liver tumours in GHtgJAK2Δhep and JAK2Δhep mice was observed 5 months later with an incidence of 76% and 68%, respectively. Histopathological analysis revealed that GHtgJAK2Δhep and JAK2Δhep tumours both displayed cellular polymorphism and expression of markers for hepatocellular malignancy, such as oval cell fraction, and eosinophilic inclusions (Supplementary Fig. S3b).

Figure 3. Liver tumourigenesis is enhanced in STAT5-deficient animals, but diminished upon loss of its upstream kinase JAK2.

(a) Kaplan-Meier plot of male mice of four distinct genotypes over a time period of 60 weeks (n ≥ 14/genotype). (b) Tumour incidence of livers of GHtgSTAT5Δhep, GHtg, GHtgJAK2Δhep and JAK2Δhep mice. At 40 weeks of age, GHtg mice developed first liver tumours. Additional deletion of STAT5 in hepatocytes led to earlier and malignant tumours, whereas deletion of JAK2 resulted in delayed tumour formation at 60 weeks of age (n ≥ 4/genotype). (c) Macroscopic appearance of tumourigenic livers at indicated time points. At 40 weeks, GHtgSTAT5Δhep mice had large steatotic and solid tumours. Tumours displayed a solid or trabecular growth pattern (n ≥ 4/genotype). (d) Representative Western blot analysis of oncogenic signalling pathways in whole liver homogenates at 40 weeks of age. HSC70 is shown as loading control (n ≥ 2/genotype). Scans of blots are presented in Supplementary Fig. S9. (e) Representative Western blot analysis of STAT proteins. As a loading control HSC70 is shown. WT and JAK2Δhep animals were injected intraperitoneally with vehicle or 2 mg/kg hGH and sacrificed 30 minutes thereafter (n = 3/treatment). Scans of blots and different exposure times of pY-STAT5 are presented in Supplementary Fig. S9. ***p < 0.001.

Aberrant GH-mediated activation of STAT3 contributes to liver tumourigenesis in STAT5-deficient mice19,20,24, which was clearly prevented in JAK2-deficient livers (Fig. 3d). In agreement, GH treatment of JAK2Δhep mice did not result in activation of STAT1/3/5 (Fig. 3e). Notably, not all GHR responsive signalling pathways require JAK2 activity30; these include GH dependent activation of SRC and ERK1/2, both of which can exert oncogenic functions in liver. However, neither SRC nor ERK1/2 was aberrantly activated in livers of GHtgJAK2Δhep and GHtgSTAT5Δhep mice (Fig. 3d), suggesting that these signalling pathways do not contribute to liver tumourigenesis in either model. These results demonstrate that hepatic JAK2 deficiency - in contrast to STAT5 deletion - delays tumour formation in the GH transgenic background.

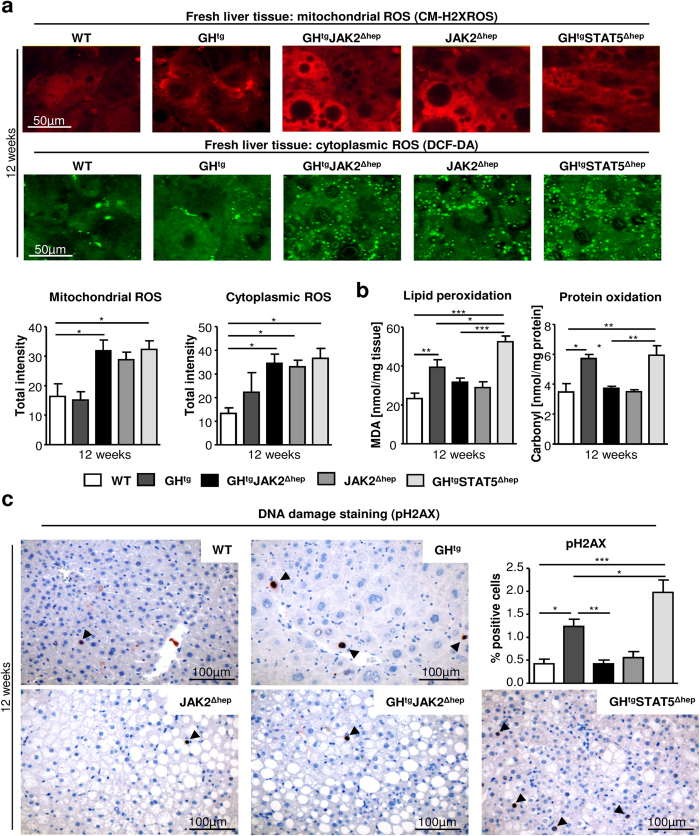

Loss of JAK2 protects against ROS-induced oxidative damage

Oxidative stress is a common feature of NAFLD and the resulting cellular damage (i.e. lipid peroxidation, protein oxidation and DNA damage)8 contributes to liver tumourigenesis. To investigate the contribution of oxidative stress to progression of steatosis upon hepatic JAK2 or STAT5 deficiency, we determined ROS production within hepatocytes in 12-week-old animals by using different dyes, which are sensitive to mitochondrial membrane potential, mitochondrial or cytoplasmic ROS. For this purpose liver tissues were freshly excised, sectioned and subsequently stained. Mitochondrial membrane potential was similar among the genotypes, while mitochondrial and cytoplasmic ROS was increased in hepatocytes of steatotic GHtgSTAT5Δhep, GHtgJAK2Δhep and JAK2Δhep livers (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Fig. S4a). Cytoplasmic ROS in GHtgJAK2Δhep, JAK2Δhep and GHtgSTAT5Δhep livers was recognised as small subcellular structures indicative for peroxisome activation. Surprisingly, despite similarly elevated ROS levels, increased DNA damage (pH2AX), protein carbonylation (indicative for protein oxidation), and malondialdehyde (MDA), a side product of lipid peroxidation, were only significantly increased in GHtgSTAT5Δhep and GHtg animals at 12 and 40 weeks of age (Fig. 4b,c; Supplementary Fig. S4b,c). These data indicate that hepatic JAK2 deficiency protects against ROS-induced DNA damage and oxidation of lipids and proteins, while STAT5 deficiency results in accelerated oxidative damage.

Figure 4. Hepatic JAK2 deficiency protects against ROS-induced lipid peroxidation, protein oxidation and DNA damage.

(a) Freshly cut livers were stained with fluorescent dyes sensitive to mitochondrial and cytoplasmic ROS. Imaging was performed with an inverted confocal microscope (n ≥ 5/genotype). (b) Lipid peroxidation was assessed by measuring its by-product malondialdehyde (MDA) at 12 weeks of age. Measurement of protein oxidation was performed using colorimetric assay (n ≥ 5/genotype). (c) Representative liver sections of 12-week-old mice stained with antibodies against phosphorylated H2AX to detect DNA damage. Quantification of positive hepatocytes by image analysis (n ≥ 5/genotype). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001.

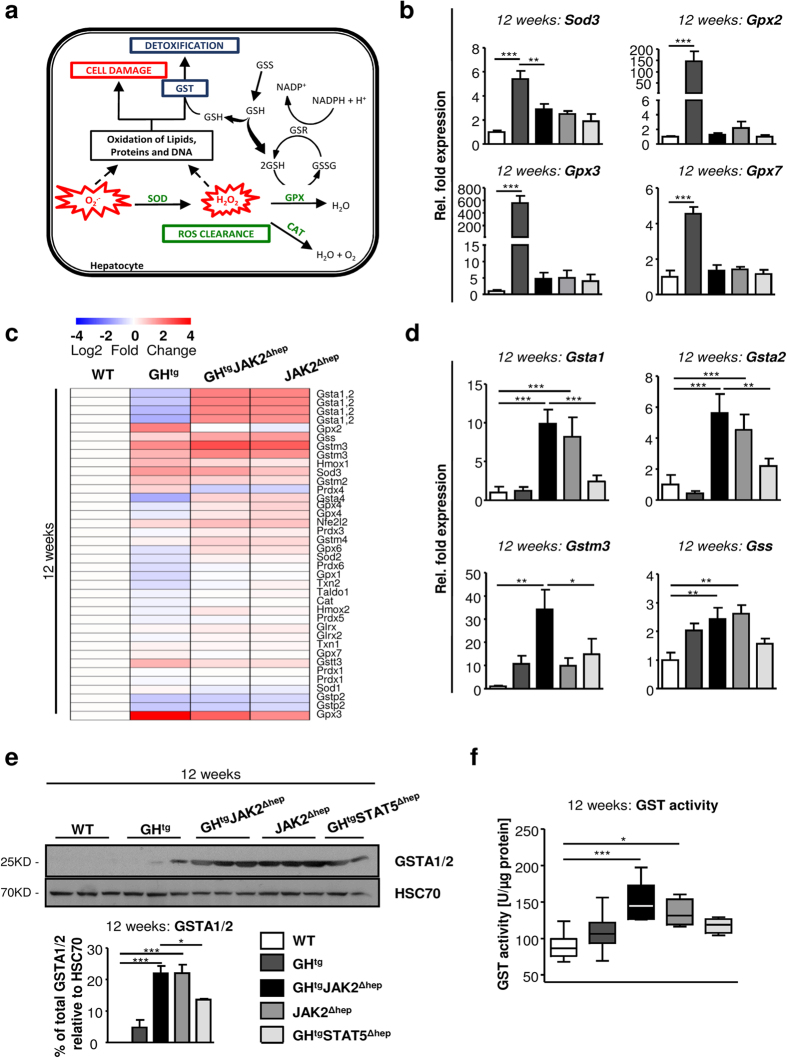

Loss of JAK2 leads to increased detoxification by glutathione S-transferases

Protection from ROS-mediated oxidative damage is conducted by several defence mechanisms, such as ROS clearance and the detoxification machinery9. Inadequate defence mechanisms result in cell damage and thereby, increase the risk for malignant transformation (Fig. 5a). Thus, to define the mechanisms underlying the different degrees of oxidative damage upon hepatic JAK2 or STAT5 deficiency, we examined the expression levels of enzymes involved in ROS clearance and detoxification. Global gene-expression analysis of enzymes governing ROS clearance revealed that the expression of superoxide dismutase 3 (Sod3), glutathione peroxidase 2 (Gpx2), Gpx3 and Gpx7 was highly upregulated in GHtg animals at 12 weeks of age (Fig. 5b,c; Supplementary Fig. S5a). SOD3, GPX2 and GPX3 execute extracellular functions and have been shown to exert anti-inflammatory effects31,32. However, expression levels were not altered in steatotic GHtgSTAT5Δhep, GHtgJAK2Δhep and JAK2Δhep livers compared to WT littermates. The second major antioxidant defence mechanism is executed by glutathione-S transferases (GST), which directly detoxify oxidized macromolecules to prevent cell damage (Fig. 5a). At 12 and 40 weeks of age, Affymetrix and qRT-PCR analyses of whole liver extracts revealed strong upregulation of Gsta1, Gsta2 and Gstm3 particularly in JAK2-deficient livers (Fig. 5c,d; Supplementary Fig. S5b,c). Additionally, the expression of glutathione synthetase (GSS), which is necessary for glutathione biosynthesis and GST functionality, was increased in GHtgJAK2Δhep and JAK2Δhep mice (Fig. 5d). In line, protein levels of GSTA1/2 and GST activity were significantly elevated in GHtgJAK2Δhep and JAK2Δhep livers (Fig. 5e,f; Supplementary Fig. S5d). Taken together, these results suggest that loss of hepatic JAK2 diminishes ROS-induced oxidative damage through increased expression and activity of GST enzymes.

Figure 5. Genetic deletion of hepatic Jak2 results in increased expression and activity of detoxifying enzymes.

(a) Schematic overview of the antioxidative defence system. SOD, CAT and GPX are the primary antioxidant enzymes which inactivate ROS into intermediates. GST catalyses the conjugation of the reduced form of GSH to oxidised products to detoxify oxidised lipids, proteins and DNA (H+: hydrogen ion, SOD: superoxide dismutase, CAT: catalase, GPX: glutathione peroxidase, GSSG: oxidized glutathione, GSH: glutathione, GSS: glutathione synthetase, GSR: glutathione reductase, GST: glutathione S-transferase). (b) By means of qRT-PCR, mRNA levels of Sod3, Gpx2, Gpx3 and Gpx7 involved in antioxidant response were measured in livers at 12 weeks of age (n = 6/genotype). Ct values were normalised to Gapdh and Rpl12a. (c) At 12 weeks of age transcriptome analysis of genes coding for enzymes involved in antioxidant defence. (d) mRNA expression levels of Gsta1, Gsta2, Gstm3 and Gss at 12 weeks of age (n = 6/genotype). Ct values were normalised to Gapdh. (e) Representative Western blot analysis of whole liver homogenates and Western blot quantification of GSTA1/2 from 12-week-old animals. As a loading control HSC70 is shown (n ≥ 2/genotype). Scans of blots are presented in Supplementary Fig. S10. (f) GST activity was assessed in livers from 12-week-old mice using a colorimetric assay (n ≥ 6/genotype). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001.

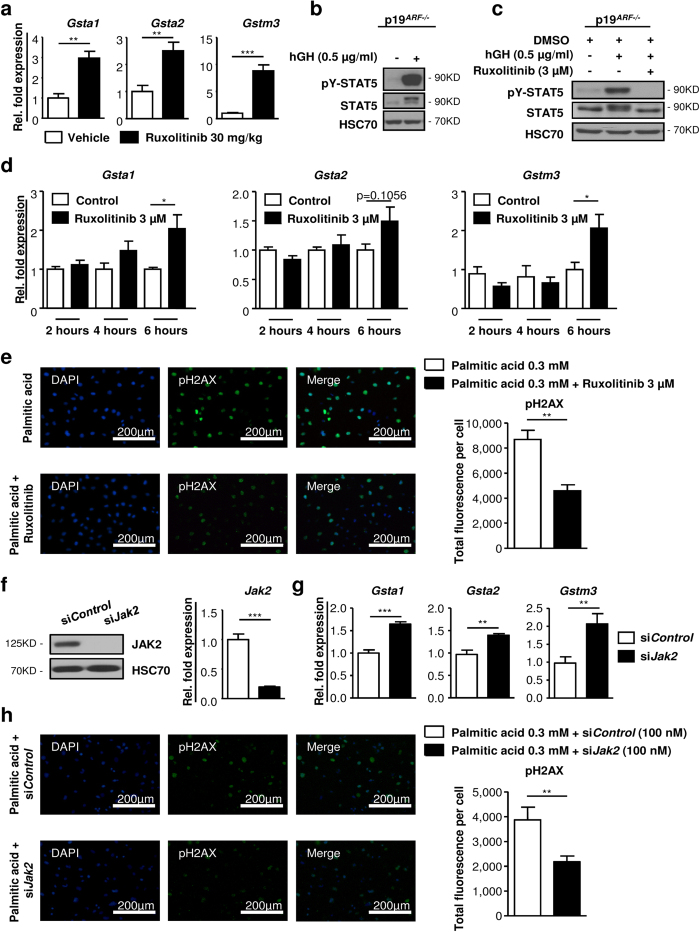

Pharmacological inhibition and siRNA-mediated knockdown of Jak2 leads to increased expression of Gst isoforms and reduced DNA damage

To verify that loss of JAK2 activity directly accounted for the induction of Gst expression, we treated WT littermates with the JAK inhibitor ruxolitinib for 2 days. Ruxolitinib treatment induced strong expression of Gsta1, Gsta2 and Gstm3, resembling the hepatic knockout of Jak2. Liver sections exhibited normal liver architecture in ruxolitinib-treated mice (Fig. 6a; Supplementary Fig. S6a). To assess whether Gst expression was hepatocyte-specific, we made use of immortalised murine p19ARF−/− hepatocytes33, which were characterised by formation of monolayers, retention of morphological features and the expression of hepatocyte-specific markers as verified by Western blotting (Supplementary Fig. S6b). p19ARF−/− hepatocytes were responsive to GH as indicated by STAT5 activation (Fig. 6b) and JAK2-STAT5 signalling could be completely inhibited by ruxolitinib treatment (Fig. 6c). Importantly, already after 6 hours of JAK2 inhibition, p19ARF−/− hepatocytes displayed increased Gsta1, Gsta2 and Gstm3 expression (Fig. 6d).

Figure 6. Pharmacological inhibition and siRNA-mediated knockdown of Jak2 induces expression of Gst isoforms and reduces DNA damage upon oxidative stress.

(a) Control littermates not expressing the AlfpCre were treated with vehicle or 30 mg/kg ruxolitinib twice daily for 2 days by oral gavage (n = 4/treatment). mRNA expression levels of Gsta1, Gsta2 and Gstm3 upon ruxolitinib treatment. Ct values were normalised to Gapdh. (b) Representative Western blot analysis showed activation of STAT5 in immortalised p19ARF−/− hepatocytes upon human GH stimulation (0.5 μg/ml). Prior to stimulation, hepatocytes were starved for 2 hours (1% FCS and without growth factors). As a loading control HSC70 is shown (n = 3 independent experiments). Scans of blots are presented in Supplementary Fig. S11. (c) After treatment with 3 μM ruxolitinib for 24 hours, p19ARF−/− hepatocytes were stimulated with 0.5 μg/ml of human GH and analysed by Western blotting. As a loading control HSC70 is shown (n = 3 independent experiments). Scans of blots are presented in Supplementary Fig. S11. (d) p19ARF−/− hepatocytes were treated with 3 μM ruxolitinib without hGH for indicated time points. mRNA expression levels of Gsta1, Gsta2 and Gstm3 were measured. Results are shown from three independent experiments. Ct values were normalised to Gapdh. (e) Immunofluorescence staining of DAPI (blue) and phosphorylated H2AX (green). p19ARF−/− hepatocytes were pre-treated 24 hours with ruxolitinib or DMSO. Cells were exposed with 0.3 mM palmitic acid (PA) for another 24 hours containing either ruxolitinib or DMSO. Fluorescence intensity was quantified by image analysis (n = 3 independent experiments). (f) p19ARF−/− hepatocytes were transfected with non-targeting siRNA (siControl) or siRNA against Jak2 (siJak2) for 48 hours. Representative Western blot analysis and mRNA expression levels showed efficient knockdown in p19ARF−/− hepatocytes. As a loading control HSC70 is shown. Scans of blots are presented in Supplementary Fig. S11. (g) p19ARF−/− hepatocytes were transfected with siJak2 or siControl for 48 hours. mRNA expression levels of Gsta1, Gsta2 and Gstm3 upon siRNA-mediated knockdown were measured. Ct values were normalised to Gapdh. (h) Immunofluorescence staining of DAPI (blue) and phosphorylated H2AX (green). p19ARF−/− hepatocytes were pre-treated 48 hours with siJak2 or siControl. Cells were exposed with 0.3 mM PA for another 24 hours. Fluorescence intensity was quantified by image analysis (n = 2 independent experiments). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001.

Next, we set out to functionally verify, if inhibition of JAK2 by ruxolitinib would reduce oxidative damage. We generated ROS-induced DNA damage in p19ARF−/− hepatocytes by H2O2 exposure. Indeed, pre-treatment with ruxolitinib led to a significant reduction of pH2AX expression in hepatocytes (Supplementary Fig. S6c). Similarly, pre-treatment of p19ARF−/− hepatocytes with ruxolitinib resulted in a pronounced reduction of pH2AX expression in hepatocytes upon palmitic acid (PA)-induced lipotoxicity (Fig. 6e)34. To exclude potential JAK2 independent effects of ruxolitinib treatment, we additionally made use of small interfering (si)RNA-mediated knockdown of Jak2. Complete knockdown in p19ARF−/− hepatocytes was accomplished after 48 hours (Fig. 6f). In accordance with ruxolitinib-treated p19ARF−/− hepatocytes, knockdown of Jak2 resulted in increased Gsta1, Gsta2 and Gstm3 expression (Fig. 6g) and reduced ROS-induced DNA-damage after H2O2 and PA exposure (Fig. 6h; Supplementary Fig. S6d).

Thus, in agreement with genetic loss of JAK2, these data imply that pharmacological inhibition and siNRA-mediated knockdown of Jak2 reduces oxidative stress-induced DNA damage, presumably, through upregulation of Gst enzymes.

Collectively, our data suggest that STAT5 deficiency aggravates liver tumourigenesis in the GHtg background due to aberrant STAT3 activation and increased oxidative damage. In contrast, JAK2 deficiency delays tumour formation in GHtg mice, which is linked to insignificant oncogenic STAT3 signalling and reduced ROS-induced oxidative damage. Our conclusion model (Supplementary Fig. S7) depicts the surprising difference between hepatic STAT5 and JAK2 deficiency with consequence for oxidative liver damage.

Discussion

Development of NAFLD has been associated with impaired GH signalling14,15. Mouse models have further linked loss of GH signalling to NAFLD by demonstrating that liver-specific deficiency of GHR, JAK2 or STAT5 results in metabolic defects, which manifest in hepatic steatosis17,18,19. HCC is a common consequence of chronic liver disease4,5. While JAK2-STAT5 signalling exerts oncogenic functions in hematopoietic cancers35, GH-activated STAT5 has a protective role in mouse models of chronic liver disease12,20,22,23,24,36.

Here, we describe that hepatic JAK2 deficiency protects against oxidative liver damage and thereby, potentially reduces the risk for liver tumourigenesis in a GHtg mouse model.

We confirm that loss of JAK2 leads to overt hepatomegaly and steatosis. This phenotype was described to depend on GH-dependent mobilisation of FFAs from WAT and their increased hepatic uptake mediated by elevated expression of PPARγ and CD3618,27. In contrast to GHtgJAK2Δhep mice, JAK2Δhep animals did not display strong increases in circulating FFAs and a depletion of WAT stores. However, even in presence of normal circulating FFA concentrations, transgenic CD36 overexpression in murine liver results in markedly elevated FA uptake and lipid storage37. Thus, the greatly increased CD36 expression in JAK2Δhep livers likely promotes hepatic FA uptake and deposition in a similar manner. CD36 is a transcriptional target of PPARγ38 and previous work links GH signalling to transcriptional repression of PPARγ18. Accordingly, hyperactivated GH signalling, as seen in GHtg mice, suppresses the transcription of PPARγ and its downstream targets, CD36 and SCD139. Conversely, disruption of GH signalling by hepatic deletion of JAK2 or STAT5 results in increased expression of Cd3618,19, which we additionally confirmed by knockdown of Jak2 in p19ARF−/− hepatocytes (Supplementary Fig. S6e). We extend these findings by demonstrating that hepatic JAK2 deficiency results in elevated protein expression of the lipogenic enzymes FAS and SCD1, both of which are frequently linked to NAFLD40,41. In agreement with the upregulation of FAS and SCD140,41, a specific increase in palmitate (C16:0), palmitoleate (C16:1) and oleate (C18:1) concentrations was observed, suggesting elevated de novo synthesis and conversion of saturated FAs into monounsaturated FAs.

A characteristic feature of NAFLD is an increased formation of ROS. Increases in hepatic FA species significantly contribute to ROS production by oxidative events7 and thereby to lipotoxicity42. Persistent oxidative stress adds to chronic liver injury and this amplifies the risk to develop liver cancer7. In line, disruption of GHR-JAK2-STAT5 signalling results in increased production of cytoplasmic and mitochondrial ROS in steatotic hepatocytes20. However, despite similar degrees of fatty degeneration and ROS production in GHtgSTAT5Δhep and GHtgJAK2Δhep livers, hepatic JAK2 deficiency delayed tumour formation in the GHtg background. In accordance with our data, increased activation of JAK2 correlates with poor overall survival in HCC patients with high circulating prolactin levels43. Furthermore, mice lacking the GHR in a model of cholestasis were largely resistant to tumour development despite an aggravation of liver fibrosis44, while a clinical study revealed very low incidence of cancer in a population suffering from a GHR mutation45. Besides the clinically approved ruxolitinib, there are more than 10 distinct JAK2 inhibitors in clinical trials46 emphasising the pharmacological relevance of this pathway.

Aberrant GH-mediated activation of STAT3 was associated with accelerated liver tumourigenesis of STAT5-deficient livers19,20,24. In agreement with the requirement of JAK2 for GH-mediated activation of STAT proteins30, excessive STAT3 activity was not observed in JAK2-deficient livers and thus presumably contributed to delayed tumour onset in GHtgJAK2Δhep mice. Intriguingly, in the absence of JAK2, elevated ROS accumulation did not correlate with augmented lipid peroxidation, protein oxidation and DNA damage. Several potential therapeutic strategies to lower oxidative stress in NAFLD have been suggested10. In particular, vitamin E supplementation is used to decrease TG accumulation and to lower lipid peroxidation10,47. Along this line, we show that JAK2 deficiency led to increased expression and activity of GSTs, a group of detoxification enzymes involved in protection against oxidative stress48. A similar increase in GST expression and activity was not detectable in STAT5-deficient livers, in which elevated ROS accumulation correlated with augmented oxidative damage. A recent study linked STAT5 activation to increased ROS production in chronic myeloid leukaemia cells by repressing antioxidant enzymes suggesting tissue-specific functions of STAT549.

In support of our in vivo findings, treatment of p19ARF−/− hepatocytes with ruxolitinib and siRNA against Jak2 not only resulted in Gst upregulation, but was also efficient in reducing H2O2 and palmitic acid induced oxidative DNA damage. Given the detoxifying role of GST isoforms upregulation in the absence of JAK2 potentially contributes to decreased oxidative damage and delayed tumour initiation in GHtgJAK2Δhep mice. The role of GSTs in NAFLD and its progression are not understood. However, a GSTM1-null genotype has been implicated in NAFLD development and this finding might be correlated with increased HCC risk in the Asian population50. GST activity was further reported to decrease with NAFLD progression accompanied by a reduced pool of glutathione, which inversely correlated with lipid peroxidation11. In conjunction, our findings provide evidence that GST enzymes - through resolution of oxidative stress - might be beneficial for the prevention of NAFLD-associated liver damage.

The expression of Gsts has been shown to be induced by nuclear factor-like 2 (NRF2), and the nuclear hormone receptors retinoic acid receptor alpha (RARα) and retinoid X receptor alpha (RXRα)51. Neither Nrf2 mRNA expression nor protein levels of RARα and RXRα were significantly upregulated in JAK2-deficient livers (Supplementary Fig. S5e). Interestingly, JAK2 can exert nuclear or peri-nuclear function in hepatocytes, mammary epithelial or hematologic cells52,53,54. This might be a possible mechanism to repress Gst induction in the presence of JAK2. However, JAK2-dependent regulation of chromatin architecture identified to date is rather associated with activating than repressive function52.

Collectively, we show that ROS-mediated oxidative damage is prevented in steatotic JAK2 deficient livers, which correlates with delayed tumour onset in the GHtg background. Importantly, in line with findings from the genetic model, our data indicate that pharmacologic JAK2 inhibition protects against oxidative damage. Further studies assessing the effectiveness of JAK2 inhibitors to lower oxidative stress may provide a rationale for the potential use in chronic liver disease.

Methods

Mice

Mice with hepatic deletion of Jak2 or Stat5 (Jak2fl/fl 25, Stat5abfl/fl; referred to as JAK2Δhep or STAT5Δhep 55) were bred with GH transgenic animals (GHtg; described in ref. 26) to generate GHtgJAK2Δhep and GHtgSTAT5Δhep mice, respectively. Littermates not expressing AlfpCre recombinase served as WT controls. The genetic background of all mice analysed was C57BL/6J × SV129. For all analyses only male mice were used. Animal experiments were performed according to an ethical animal license protocol approved by the authorities of the Austrian government and the Medical University of Vienna. Maintenance and experimental procedures of mice are described in detail in the Supplementary materials and methods (see Supplementary information).

Serum biochemistry

Serum levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate-aminotransferase (AST) were determined using the test strip-based Reflotron Plus analyser (Roche). Free fatty acid levels were assessed photometrically using the NEFA-HR(2) kit (Wako).

Measurement of hepatic metabolites

Hepatic triglycerides (CaymanChemical), lipid peroxidation, protein oxidation and GST activity (BioVision) were determined using commercially available colorimetric assays. The measurement of ROS levels and hepatic fatty acid is described in Supplementary materials and methods (see Supplementary information).

Immunoblotting and immunohistochemistry

Western blot analyses and immunohistochemistry were performed according to standard protocols. Antibodies used are listed in detail in the Supplementary materials and methods (see Supplementary information).

Microarray analysis

At 12 and 40 weeks, total RNA from 3 livers/genotype (WT, GHtg, GHtgJAK2Δhep and JAK2Δhep) were isolated using the RNAeasy Kit (#74104; Quiagen) and hybridised to GeneChip Mouse Gene 1.0 ST array (Affymetrix). Microarray data and description of the experimental design is deposited under ArrayExpress, with the accession number: E-MTAB-3774. The detailed analysis is provided in the Supplementary materials and methods (see Supplementary information).

Analysis of gene expression by quantitative PCR

Total RNA was isolated with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) and reverse transcribed using Revert Aid cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The detailed method together with the primer sequences is provided in the Supplementary materials and methods (see Supplementary information).

Cell Culture

Hepatocytes of p19ARF−/− mice were isolated and propagated as described33. Maintenance of p19ARF−/− hepatocytes and in vitro experiments are described in the Supplementary materials and methods (see Supplementary information).

Statistics

All values are represented as means ± standard error of the mean if not indicated otherwise. Statistical significance was evaluated using a confidence interval of 95% with either one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s, Dunns’ or Bonferroni’s post-hoc test for multiple comparison or two-tailed student’s t-test for the comparison of two groups. Differences between experimental groups were considered significant at *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001. All calculations were performed using GraphPad Prism software (La Jolla, CA).

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Themanns, M. et al. Hepatic Deletion of Janus Kinase 2 Counteracts Oxidative Stress in Mice. Sci. Rep. 6, 34719; doi: 10.1038/srep34719 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Safia Zahma and Margit Gogg-Kamerer for their excellent technical assistance. This work was supported by grant SFB F28 (F2807-B20) and SFB F47 (F4707-B20) from the Austrian Science Fund (FWF).

Footnotes

Author Contributions M.T. designed and performed experiments, analysed and interpreted data, acquired data and wrote the manuscript. K.M.M. performed experiments, analyses and interpretation of data, and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. S.M.K. performed hepatic fatty acid analysis; N.G.-S. analysed tumour sections; T.M. performed microarray analysis; D.K. performed Western blot and siRNA experiments; J.B. performed part of qRT-PCR experiments; J.P.-P. contributed to ROS measurement in liver tissue; K.F. contributed to initiation of this project and performed first analysis of the mice; D.S. isolated immortalized p19ARF−/− hepatocytes and M.S. executed immunohistochemical stainings. L.M.T., M.H.H. and J.H. were responsible for professional analysis of histologic sections and critically revised the manuscript. E.Z.-B. provided financial support and recorded data with M.T., and critically revised the manuscript. K.-U.W., W.M., F.G., X.H., L.K. and A.V.K. critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. R.M. was responsible for study concept and supervision, analyses and interpretation of data, critically revised the manuscript, and acquired funding. All authors had final approval of the submitted version.

References

- Duan X. F., Tang P., Li Q. & Yu Z. T. Obesity, adipokines and hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Cancer 133, 1776–1783, doi: 10.1002/ijc.28105 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baffy G., Brunt E. M. & Caldwell S. H. Hepatocellular carcinoma in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: an emerging menace. J Hepatol. 56, 1384–1391, doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.10.027 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stojsavljevic S., Gomercic Palcic M., Virovic Jukic L., Smircic Duvnjak L. & Duvnjak M. Adipokines and proinflammatory cytokines, the key mediators in the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 20, 18070–18091, doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i48.18070 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ertle J. et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease progresses to hepatocellular carcinoma in the absence of apparent cirrhosis. Int J Cancer 128, 2436–2443, doi: 10.1002/ijc.25797 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradis V. et al. Hepatocellular carcinomas in patients with metabolic syndrome often develop without significant liver fibrosis: a pathological analysis. Hepatology 49, 851–859, doi: 10.1002/hep.22734 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzawa N. et al. Lipid-induced oxidative stress causes steatohepatitis in mice fed an atherogenic diet. Hepatology 46, 1392–1403, doi: 10.1002/hep.21874 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradies G., Paradies V., Ruggiero F. M. & Petrosillo G. Oxidative stress, cardiolipin and mitochondrial dysfunction in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 20, 14205–14218, doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i39.14205 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaunig J. E., Kamendulis L. M. & Hocevar B. A. Oxidative stress and oxidative damage in carcinogenesis. Toxicol Pathol. 38, 96–109, doi: 10.1177/0192623309356453 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W., Baker S. S., Baker R. D. & Zhu L. Antioxidant Mechanisms in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Curr Drug Targets (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polimeni L. et al. Oxidative stress: New insights on the association of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and atherosclerosis. World J Hepatol. 7, 1325–1336, doi: 10.4254/wjh.v7.i10.1325 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardwick R. N., Fisher C. D., Canet M. J., Lake A. D. & Cherrington N. J. Diversity in antioxidant response enzymes in progressive stages of human nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Drug Metab Dispos. 38, 2293–2301, doi: 10.1124/dmd.110.035006 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baik M., Yu J. H. & Hennighausen L. Growth hormone-STAT5 regulation of growth, hepatocellular carcinoma, and liver metabolism.Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1229, 29–37, doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06100.x (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riordan J. D. & Nadeau J. H. Modeling progressive non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in the laboratory mouse. Mamm Genome 25, 473–486, doi: 10.1007/s00335-014-9521-3 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laron Z., Ginsberg S. & Webb M. Nonalcoholic fatty liver in patients with Laron syndrome and GH gene deletion - preliminary report. Growth hormone & IGF research : official journal of the Growth Hormone Research Society and the International IGF Research Society 18, 434–438, doi: 10.1016/j.ghir.2008.03.003 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fusco A. et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is associated with increased GHBP and reduced GH/IGF-I levels. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 77, 531–536, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2011.04291.x (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller K. M. et al. Hepatic growth hormone and glucocorticoid receptor signaling in body growth, steatosis and metabolic liver cancer development. Molecular and cellular endocrinology 361, 1–11, doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2012.03.026 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y. et al. Liver-specific deletion of the growth hormone receptor reveals essential role of growth hormone signaling in hepatic lipid metabolism. The Journal of biological chemistry 284, 19937–19944, doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.014308 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sos B. C. et al. Abrogation of growth hormone secretion rescues fatty liver in mice with hepatocyte-specific deletion of JAK2. J Clin Invest 121, 1412–1423, doi:42894 [pii] 10.1172/JCI42894 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Y. et al. Loss of signal transducer and activator of transcription 5 leads to hepatosteatosis and impaired liver regeneration. Hepatology 46, 504–513, doi: 10.1002/hep.21713 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller K. M. et al. Impairment of hepatic growth hormone and glucocorticoid receptor signaling causes steatosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in mice. Hepatology 54, 1398–1409, doi: 10.1002/hep.24509 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi S. Y. et al. Hepatocyte-specific deletion of Janus kinase 2 (JAK2) protects against diet-induced steatohepatitis and glucose intolerance. The Journal of biological chemistry 287, 10277–10288, doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.317453 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosui A. et al. Loss of STAT5 causes liver fibrosis and cancer development through increased TGF-{beta} and STAT3 activation. J Exp Med. 206, 819–831, doi:jem.20080003 [pii] 10.1084/jem.20080003 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J. H., Zhu B. M., Riedlinger G., Kang K. & Hennighausen L. The liver-specific tumor suppressor STAT5 controls expression of the reactive oxygen species-generating enzyme NOX4 and the proapoptotic proteins PUMA and BIM in mice. Hepatology 56, 2375–2386, doi: 10.1002/hep.25900 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedbichler K. et al. Growth-hormone-induced signal transducer and activator of transcription 5 signaling causes gigantism, inflammation, and premature death but protects mice from aggressive liver cancer. Hepatology 55, 941–952, doi: 10.1002/hep.24765 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krempler A. et al. Generation of a conditional knockout allele for the Janus kinase 2 (Jak2) gene in mice. Genesis 40, 52–57, doi: 10.1002/gene.20063 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snibson K. J., Bhathal P. S., Hardy C. L., Brandon M. R. & Adams T. E. High, persistent hepatocellular proliferation and apoptosis precede hepatocarcinogenesis in growth hormone transgenic mice. Liver 19, 242–252 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordstrom S. M., Tran J. L., Sos B. C., Wagner K. U. & Weiss E. J. Disruption of JAK2 in adipocytes impairs lipolysis and improves fatty liver in mice with elevated GH. Mol Endocrinol. 27, 1333–1342, doi: 10.1210/me.2013-1110 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollenweider P., von Eckardstein A. & Widmann C. HDLs, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome. Handb Exp Pharmacol 224, 405–421, doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-09665-0_12 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanke R., Hermanns W., Folger S., Wolf E. & Brem G. Accelerated growth and visceral lesions in transgenic mice expressing foreign genes of the growth hormone family: an overview. Pediatr Nephrol. 5, 513–521 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barclay J. L. et al. In vivo targeting of the growth hormone receptor (GHR) Box1 sequence demonstrates that the GHR does not signal exclusively through JAK2. Mol Endocrinol. 24, 204–217, doi: 10.1210/me.2009-0233 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurila J. P., Laatikainen L. E., Castellone M. D. & Laukkanen M. O. SOD3 reduces inflammatory cell migration by regulating adhesion molecule and cytokine expression. PloS one 4, e5786, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005786 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brigelius-Flohe R. & Kipp A. P. Physiological functions of GPx2 and its role in inflammation-triggered carcinogenesis.Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1259, 19–25, doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06574.x (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikula M. et al. Immortalized p19ARF null hepatocytes restore liver injury and generate hepatic progenitors after transplantation. Hepatology 39, 628–634, doi: 10.1002/hep.20084 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Y., Wang D., Topczewski F. & Pagliassotti M. J. Saturated fatty acids induce endoplasmic reticulum stress and apoptosis independently of ceramide in liver cells. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 291, E275–E281, doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00644.2005 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valentino L. & Pierre J. JAK/STAT signal transduction: regulators and implication in hematological malignancies. Biochem Pharmacol. 71, 713–721, doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.12.017 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y. et al. Evolution of hepatic steatosis to fibrosis and adenoma formation in liver-specific growth hormone receptor knockout mice. Frontiers in endocrinology 5, 218, doi: 10.3389/fendo.2014.00218 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koonen D. P. et al. Increased hepatic CD36 expression contributes to dyslipidemia associated with diet-induced obesity. Diabetes 56, 2863–2871, doi: 10.2337/db07-0907 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J. et al. Hepatic fatty acid transporter Cd36 is a common target of LXR, PXR, and PPARgamma in promoting steatosis. Gastroenterology 134, 556–567, doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.11.037 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran-Salvador E. et al. Role for PPARgamma in obesity-induced hepatic steatosis as determined by hepatocyte- and macrophage-specific conditional knockouts. FASEB journal: official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology 25, 2538–2550, doi: 10.1096/fj.10-173716 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotronen A. et al. Hepatic stearoyl-CoA desaturase (SCD)-1 activity and diacylglycerol but not ceramide concentrations are increased in the nonalcoholic human fatty liver. Diabetes 58, 203–208, doi: 10.2337/db08-1074 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen-Urstad A. P. & Semenkovich C. F. Fatty acid synthase and liver triglyceride metabolism: housekeeper or messenger? Biochimica et biophysica acta 1821, 747–753, doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2011.09.017 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trauner M., Arrese M. & Wagner M. Fatty liver and lipotoxicity. Biochimica et biophysica acta 1801, 299–310, doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2009.10.007 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh Y. T., Lee K. T., Tsai C. J., Chen Y. J. & Wang S. N. Prolactin promotes hepatocellular carcinoma through Janus kinase 2. World J Surg. 36, 1128–1135, doi: 10.1007/s00268-012-1505-4 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiedl P. et al. Growth hormone resistance exacerbates cholestasis-induced murine liver fibrosis. Hepatology 61, 613–626, doi: 10.1002/hep.27408 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guevara-Aguirre J. & Rosenbloom A. L. Obesity, diabetes and cancer: insight into the relationship from a cohort with growth hormone receptor deficiency. Diabetologia 58, 37–42, doi: 10.1007/s00125-014-3397-3 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchert M., Burns C. J. & Ernst M. Targeting JAK kinase in solid tumors: emerging opportunities and challenges. Oncogene, doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.150 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanyal A. J. et al. A pilot study of vitamin E versus vitamin E and pioglitazone for the treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2, 1107–1115 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veal E. A., Toone W. M., Jones N. & Morgan B. A. Distinct roles for glutathione S-transferases in the oxidative stress response in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. The Journal of biological chemistry 277, 35523–35531, doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111548200 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgeais J. et al. Oncogenic STAT5 signaling promotes oxidative stress in chronic myeloid leukemia cells by repressing antioxidant defenses. Oncotarget (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naik A., Kosir R. & Rozman D. Genomic aspects of NAFLD pathogenesis. Genomics 102, 84–95, doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2013.03.007 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai G. et al. Retinoid X receptor alpha Regulates the expression of glutathione s-transferase genes and modulates acetaminophen-glutathione conjugation in mouse liver. Molecular pharmacology 68, 1590–1596, doi: 10.1124/mol.105.013680 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson M. A. et al. JAK2 phosphorylates histone H3Y41 and excludes HP1alpha from chromatin. Nature 461, 819–822, doi: 10.1038/nature08448 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson J., Bjursell G. & Kannius-Janson M. Nuclear Jak2 and transcription factor NF1-C2: a novel mechanism of prolactin signaling in mammary epithelial cells. Mol Cell Biol. 26, 5663–5674, doi: 10.1128/MCB.02095-05 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobie P. E. et al. Constitutive nuclear localization of Janus kinases 1 and 2. Endocrinology 137, 4037–4045, doi: 10.1210/endo.137.9.8756581 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engblom D. et al. Direct glucocorticoid receptor-Stat5 interaction in hepatocytes controls body size and maturation-related gene expression. Genes Dev 21, 1157–1162, doi: 10.1101/gad.426007 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.