Abstract

Clonal hematopoiesis (CH) in aplastic anemia (AA) has been closely linked to the evolution of late clonal disorders, including paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria and myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS)/acute myeloid leukemia (AML), which are common complications after successful immunosuppressive therapy (IST). With the advent of high-throughput sequencing of recent years, the molecular aspect of CH in AA has been clarified by comprehensive detection of somatic mutations that drive clonal evolution. Genetic abnormalities are found in ∼50% of patients with AA and, except for PIGA mutations and copy-neutral loss-of-heterozygosity, or uniparental disomy (UPD) in 6p (6pUPD), are most frequently represented by mutations involving genes commonly mutated in myeloid malignancies, including DNMT3A, ASXL1, and BCOR/BCORL1. Mutations exhibit distinct chronological profiles and clinical impacts. BCOR/BCORL1 and PIGA mutations tend to disappear or show stable clone size and predict a better response to IST and a significantly better clinical outcome compared with mutations in DNMT3A, ASXL1, and other genes, which are likely to increase their clone size, are associated with a faster progression to MDS/AML, and predict an unfavorable survival. High frequency of 6pUPD and overrepresentation of PIGA and BCOR/BCORL1 mutations are unique to AA, suggesting the role of autoimmunity in clonal selection. By contrast, DNMT3A and ASXL1 mutations, also commonly seen in CH in the general population, indicate a close link to CH in the aged bone marrow, in terms of the mechanism for selection. Detection and close monitoring of somatic mutations/evolution may help with prediction and diagnosis of clonal evolution of MDS/AML and better management of patients with AA.

Medscape Continuing Medical Education online

This activity has been planned and implemented in accordance with the Essential Areas and policies of the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education through the joint providership of Medscape, LLC and the American Society of Hematology.

Medscape, LLC is accredited by the ACCME to provide continuing medical education for physicians.

Medscape, LLC designates this Journal-based CME activity for a maximum of 1.0 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

All other clinicians completing this activity will be issued a certificate of participation. To participate in this journal CME activity: (1) review the learning objectives and author disclosures; (2) study the education content; (3) take the post-test with a 75% minimum passing score and complete the evaluation at http://www.medscape.org/journal/blood; and (4) view/print certificate. For CME questions, see page 464.

Disclosures

Laurie Barclay, freelance writer and reviewer, Medscape, LLC, owns stock, stock options, or bonds from Pfizer. Associate Editor Jean Soulier and the author declare no competing financial interests.

Learning objectives

Distinguish clonal hematopoiesis (CH) and somatic mutations driving clonal evolution in aplastic anemia (AA), based on a review.

Determine the prognostic significance of somatic mutations driving clonal evolution in AA.

Identify somatic mutations unique to AA vs those also commonly seen in CH in the general population.

Release date: July 21, 2016; Expiration date: July 21, 2017

Introduction

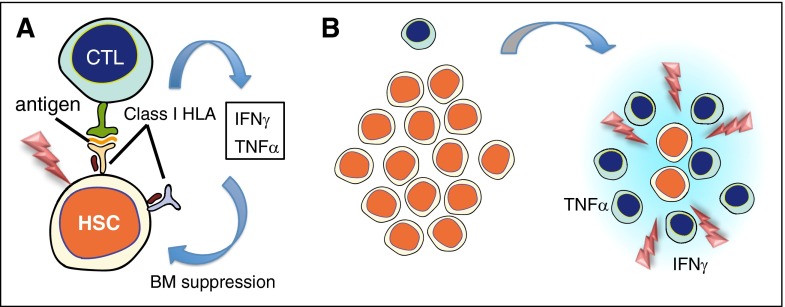

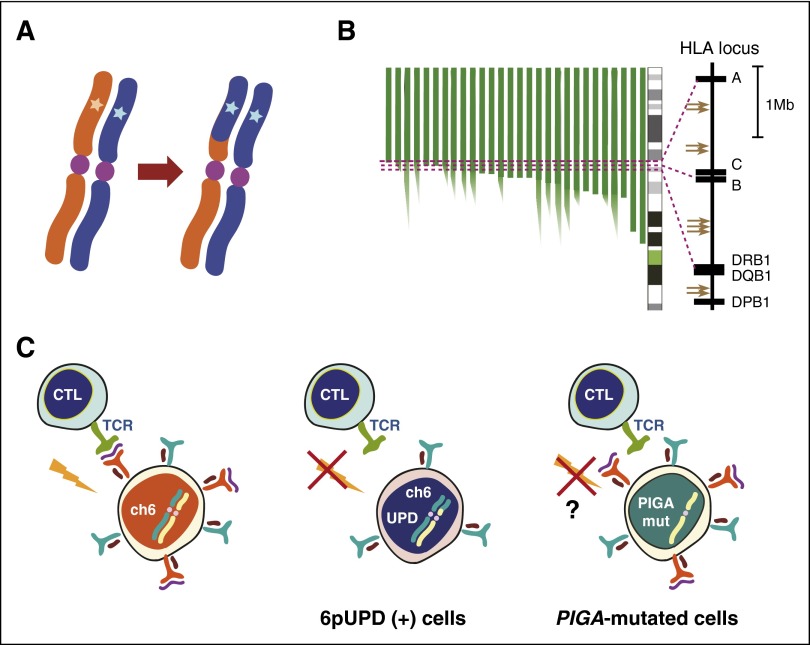

Acquired aplastic anemia (AA) is a prototype of bone marrow (BM) failure caused by immune-mediated destruction of hematopoietic stem and/or progenitor cells, where autoreactive T cells are supposed to play a central role (Figure 1).1-6 Although almost uniformly terminating in a fatal outcome in a previous era, management of AA has drastically improved since the late 1970s with the introduction of allogeneic stem cell transplantation and IST, as well as optimized supportive care.5 However, the entire picture of the disease is more complicated than expected for a simple immune-mediated marrow failure. Among others, the frequent development of late clonal diseases, including paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) and myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS)/acute myeloid leukemia (AML), is known as an enigmatic complication in AA, which may not instantaneously be understood under the category of immune-mediated disorders.7,8 The enigma is further highlighted by the evidence suggesting the presence of clonal hematopoiesis (CH), even in patients who do not develop apparent clonal diseases.9 It should be noted that clonal evolution (ie, evolution of clones) does not necessarily mean the development of cancer or any other diathesis, because it can be compatible with normal homeostasis.10,11

Figure 1.

Immune-mediated mechanism of AA and clonal evolution. (A) AA is thought to be initiated by recognition and destruction of HSCs by CTLs, which recognize some unknown antigen present on HSCs via their HLA class I molecule. Supporting this hypothesis is a limited usage of T-cell receptor Vβ subsets at diagnosis, suggestive of the presence of oligoclonal expansion of CD8+CD28− T cells, which diminish or disappear with successful IST.1-3 Overproduction of inflammatory cytokines, including interferon γ (IFNγ) and tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα), from aberrantly activated immune cells and stromal microenvironments is also suggested to make a significant contribution to BM failure, in which the role of FAS-mediated apoptosis has been implicated.4 (B) During and/or after immune-mediated BM destruction, a rapid expansion of residual cells (which escaped destruction) occurs, whereby cells carrying mutations achieve clonal dominance and may progress to malignant proliferation. CTL, cytotoxic T cell; HSC, hematopoietic stem cell; IST, immunosuppressive therapy.

Indeed, clonality in AA has been one of the long-standing issues in hematology, which was first implicated by Dameshek asking the question, What do AA, PNH, and hypoplastic leukemia have in common?12 Since then, many authors have revisited his riddle, which could now be rephrased as, What is the common underlying mechanism for, and the link between, CH and the evolution of clonal disorders in AA?8 More recently, the issue has been newly addressed by using revolutionized sequencing technologies, unmasking a unique picture of CH in AA frequently accompanied by somatic mutations commonly seen in myeloid malignancies.13-18 Combined with seminal findings on CH in aged normal individuals,19-21 as well as on preleukemic clones22 in patients with hematologic malignancies,23-25 the finding on somatic mutations in AA provides new insight into the origin and the mechanism of frequent CH in AA and its impact on the late development of MDS and AML.13,15,18 This review summarizes recent progress in the current understanding of CH in AA in relation to the pathogenesis of late clonal diseases.

Late clonal diseases in AA

The early evidence suggesting a link between AA and clonality was an unduly high incidence of PNH and MDS/AML among patients with AA.8 Although their incidence substantially increases among patients who are successfully treated by IST,9,12 the complication of clonal diseases seems to be an intrinsic feature of AA irrespective of IST, because it had long been noted even before the widespread use of IST.26

PNH is a unique form of BM failure characterized by acquired hemolytic anemia and thrombosis, which is caused by a clonal expansion of cells derived from a hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) carrying a somatic mutation involving the PIGA gene.27 PIGA-mutated cells show defective cell surface expression of glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored proteins, such as CD55 and CD59, which is responsible for the vulnerability to complement-mediated hemolysis.27 AA and PNH are closely related conditions: AA may develop during the course of PNH and vice versa (AA/PNH syndrome), both being predisposed to AML and MDS.28,29 Complication of clinically relevant PNH has been described in 15% to 25% of the patients with AA treated by IST.30-35 Moreover, regardless of typical manifestations of PNH, GPI anchor–deficient, “PNH-type” cells are detectable at even higher frequencies (up to 67%) when assessed by sensitive flow cytometry using antibodies to CD55 or CD59 and/or fluorescent aerolysin (FLAER).36,37

Another major category of late clonal diseases includes MDS and AML. The cumulative incidence of MDS/AML increases after IST, ranging from 5% to 15% within the observation period of 5 to 11.3 years.35,38-40 Because the development of MDS/AML consistently conveys a dismal prognosis in AA patients, it is of particular importance to predict, diagnose, and initiate due interventions to these complications during the course of AA. However, this is often complicated by difficulty in diagnosing MDS among patients with AA, which represents a major challenge to clinicians and hematopathologists.

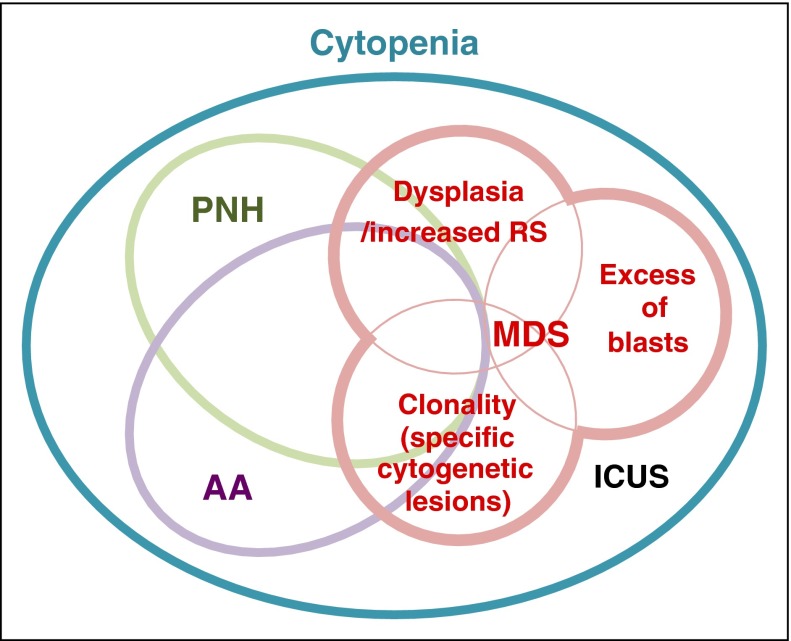

Diagnosing MDS in AA patients

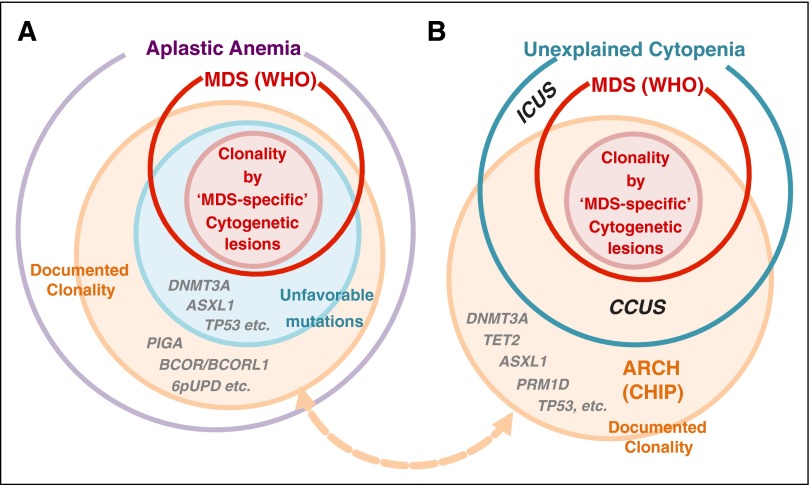

MDS is defined as refractory cytopenia caused by a neoplastic proliferation of clones committed to the myeloid lineage. The clones are thought to be neoplastic, in that their growth is no longer compatible with normal hematopoiesis, causing ineffective production of mature blood cells, enhanced apoptosis, and even progression to AML, although the clinical presentation is highly variable.41,42 Thus, at least conceptually, clonality is an essential requisite for the pathophysiology of MDS, but for the sake of clinical/pathological diagnosis, clinicians and pathologists usually diagnose the involvement of a neoplastic process primarily relying on cell morphology, in which the presence of excess blasts (≥5%) (propensity to leukemia) and/or dysplasia (in ≥10% of myeloid cells) with or without increased (≥15%) ring sideroblasts (deregulated myelopoiesis) empirically, but consistently, indicates that the defective hematopoiesis is caused by malignant clones, although morphologic examination may not necessarily be consistent between observers (Figure 2).41 Alternatively, direct demonstration of a malignant clonal process by cytogenetics can establish the diagnosis of MDS, even in the absence of dysplasia or increased blast counts, but the borderline between malignant and benign lesions is obscured: a set of abnormalities, including −7/del(7q), −5/del(5q), del(13q), del(11q), del(12p)/t(12p), del(17p)/t(17p)/i(17q), idic(X)(q13), and other balanced and unbalanced translocations, is proposed to support the diagnosis of MDS irrespective of morphology, whereas −Y, +8, and del(20q) as a sole abnormality may not, because they can be found in aged, apparently normal individuals.41,43,44 A substantial proportion of patients with persistent cytopenia lack conclusive morphology and cytogenetics and may presumptively be classified as ICUS.45,46

Figure 2.

Overlaps between AA, PNH, and MDS. Although conceptually representing discrete disease entities, AA, PNH, and MDS frequently coexist or show mutual transitions within a same patient, apart from the ambiguity in actual diagnosis due to the lack of conclusive evidence or misdiagnosis because of resembling clinical presentations. Immune-mediated BM destruction can occur at the same time of emergence of PNH or evolution of malignant clones, causing a diagnostic overlap between these different disease concepts. Increased ring sideroblasts (RS) are rarely seen in AA. ICUS, idiopathic cytopenia of undetermined significance.

The difficulty in diagnosing MDS among AA patients lies in the fact that both conditions often show indistinguishable phenotypes and may even coexist in the same patients, although patients with AA are nevertheless at high risk for MDS development. Many AA patients who ever responded to IST are still cytopenic and, even when a complete response is obtained, recurrence is common. In MDS, BM is typically normo- to hypercellular, but ∼10% of MDS patients show hypocellular marrow, mimicking nonsevere AA. Conversely, AA often displays mild to moderate dysplasia, especially in the erythroid lineage.47 Several drugs (eg, antimetabolites) and viral infections can also produce an apparently dysplastic marrow picture. Accurate evaluation of increased blasts and the presence of myeloid dysplasia in the face of severely hypoplastic marrow is another diagnostic challenge.48 Lastly, clonality is common among AA patients as seen below, further obscuring the border between AA and MDS.

Skewed X-chromosome inactivation

In early studies, clonality in AA and other conditions was evaluated by detecting nonrandom X-chromosome inactivation (NRXI; ie, skewing from the expected 1:1 ratio for random lyonization).49 van Kamp et al reported NRXI in 13 of 18 evaluable cases with AA.50 Ohashi51 and Mortazavi et al52 also reported high frequencies (∼40%) of NRXI, whereas frequencies are lower in other studies (11%-20%). The discrepancy seems to be explained partly by small sample sizes and also by different methods and genes/loci used for the detection of NRXI.9,49 The interpretation of NRXI is further complicated by the presence of extreme skewing (>3:1) in normal females, which can occur during normal development (NRXI in neonates) but also can be acquired during normal aging. In a large study using a highly reliable human androgen receptor assay (HUMARA), NRXI was seen in 37.9% of normal females aged >60 years vs 16.4% of those aged 28 to 32 years and 8.6% of neonates.53,54

Abnormal cytogenetics in AA

Clonality is also evidenced by cytogenetic abnormalities, which have been reported in 4% to 11% of AA cases,8,18,55-58 although difficulty in obtaining sufficient numbers of metaphases from the failed marrow could underestimate the real frequency, particularly at the time of diagnosis. Predominant lesions are numerical abnormalities, which include those commonly seen in myeloid malignancies, such as +8, −7, and del(5q), whereas other lesions, including +6 and +15, are rarely seen in MDS/AML. Among these, MDS-specific abnormalities defined in the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria would support the diagnosis of MDS, even without definitive morphological evidence. Especially, −7 is most frequently seen with a possible association with the use of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, and consistently predicts a poor clinical outcome in AA.35,38,40 For other lesions, their diagnostic value for MDS/AML has not been established and their presence by itself does not support the diagnosis of MDS. Del(13q) is a recurrent chromosomal abnormality assigned to MDS-specific cytogenetic lesions in the WHO criteria, although recent studies suggest that del(13q)-positive MDS cases might be better related to AA, on the basis of their excellent response to IST.59-61

Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) array–based karyotyping can complement conventional cytogenetics by enabling metaphase-independent detection of copy number abnormalities (CNAs), and despite a compromised sensitivity for lesions carried by <20% of total cells, it reveals more abnormalities than conventional karyotyping, also unmasking small cryptic lesions and copy-neutral, uniparental disomy (UPD), which otherwise escape conventional karyotyping.62,63 Among these most frequently observed are 6pUPDs, which are recognized on visual inspection of SNP array karyotyping in ∼9% of AA cases and, with more sensitive evaluation of array signals, detected in an additional 4% of the cases.16,18,63

Somatic mutations in AA

Somatic mutations are more reliable and sensitive markers for detecting clonal populations than NRXI or cytogenetics. The revolutionized technologies of next-generation DNA sequencing (NGS), together with the accumulated knowledge about the major driver mutations in MDS/AML,42,64 have prompted investigations on somatic mutations in AA in relation to clonal evolution to MDS/AML. Thus, since the first report by Lane et al,13 there have been several NGS-based mutation studies on AA during the past 2 years reporting varying mutation frequencies ranging from 5.3% to 72%13-18 (Table 1). Among these studies, mutations were most comprehensively studied by Yoshizato et al, who surveyed mutations in 106 genes commonly mutated in myeloid cancers in 439 patients using targeted-capture deep sequencing.18 AML/MDS-associated mutations were identified in 157 (35.8%) patients.65 Mutations were more frequently found in older patients and were dominated by age-dependent C to G transitions. About one-third of patients had multiple mutations. When SNP array karyotyping results were combined, clonality was demonstrated in 47% of the total cohort. The mean allelic burden of mutations was substantially smaller in AA compared with MDS: 75% of mutations had <10% of allelic burden. The majority of mutations (58/79) detected after IST were shown to be already present at the time of diagnosis, albeit at a much lower allele frequency in most cases examined. Mutations were present in multilineage compartments in 6 of 6 cases, including HSCs, common myeloid progenitors, and erythroid progenitors, as well as in a minor fraction of T cells, suggesting that the mutations occurred at a stem cell level.

Table 1.

Somatic mutations in AA

| Study | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lane et al13 | Kulasekararaj et al15 | Heuser et al14 | Babushok et al16 | Yoshizato et al18 | ||

| N = 39 | N = 150 | N = 38 | N = 22 | N = 439 (All) | N = 256 (NIH) | |

| Ratio of male to female (M/F, n) | 1.3 (22/17) | 0.9 (71/79) | 0.9 (18/20) | 0.7 (9/13) | 1.3 (244/195) | 1.6 (157/99) |

| Median age, y (range) | 34.8 (4-65.7) | 44 (17-84) | 30 (9-79) | 14.5 (1.5-61) | 40.5 (2.5-88) | 29.5 (2.5-82.5) |

| SAA/VSAA, n (%) | 29 (74) | 74 (49) | 27 (71) | 9 (41) | 344 (78) | 256 (100) |

| Serially collected samples, n | — | — | — | — | 82 | 62 |

| Platform for sequencing | ||||||

| Targeted exons | 219 genes | 835 genes (n = 57) | 42 genes | — | 106 genes | |

| Whole exome, n | — | — | — | 22 | 52 | 35 |

| Mutated genes, n (%) | ||||||

| DNMT3A | 1 (2.6) | 8 (5.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0%) | 37 (8.4) | 18 (7.0) |

| ASXL1 | 2 (5.1) | 12 (8.0) | 1 (2.6) | 1 (4.5) | 27 (6.2) | 17 (6.6) |

| BCOR/BCORL1 | 0 (0) | 6 (4.0) | 0 (0) | 1 (4.5) | 41 (9.3) | 28 (10.9) |

| PIGA | ND | 18 (12.0) | ND | 9 (40.9) | 33 (7.5) | 25 (9.8) |

| Other genes* | 6 (15.1) | 1 (2.6) | 5 (22.7) | 67 (15.3) | 29 (6.6) | |

| Any genes | 9 (23.1) | 29 (19.3) | 2 (5.3) | 16 (72.7) | 157 (35.8) | 90 (35.2) |

| Excluding PIGA alone | 9 (23.1) | 29 (19.3) | 2 (5.3) | 137 (31.2) | 74 (28.9) | |

| Clone size | ||||||

| Median (range) (%) | ND | 20 (1.5-68) | ND | ND | 15.4 (2.4-96.4) | 15.2 (2.4-76.7) |

| Clone size <10%, n (%)† | 7 (78) | 11 (14) | 0 (0) | 2 (9.1) | 130 (29.6) | 79 (30.9) |

| Cytogenetic abnormalities, n (%) | ND | 3 (7.9) | 2 (9.1) | 20 (8.5) | 9 (3.8) | |

| 6pUPD (+) clone, n (%) | ND | 1 | ND | 3 (13.6) | 55 (13.2) | 31 (13.2) |

| PNH clone, n (%) | 4 (10)‡ | 85 (57) | 17 (45) | 10 (46) | 221 (50.3) | 110 (43.0) |

| IST, n (%) | ||||||

| Yes | 19 (49) | 107 (71.3) | ND | 20 (91) | 403 (92.4) | 256 (100) |

| No | 20 (51) | 43 (28.7) | ND | 2 (9) | 33 (7.6) | 0 (0) |

| Transformation to MDS/AML, n (%) | ND | 17 (11.3) | ND | ND | 47 (10.7) | 36 (14.1) |

F, female; M, male; ND, not determined; NIH, National Institutes of Health; SAA, severe AA; VSAA, very severe AA; —, no corresponding samples.

Excluding DNMT3A, ASXL1, BCOR/BCORL1, and PIGA.

Maximum clone size in mutation-positive cases.

Variant allele frequency >5%.

Kulasekararaj et al also surveyed somatic mutations in 150 patients, first by targeted-capture sequencing of 835 candidate genes in the discovery cohort (n = 57), followed by NGS-based amplicon sequencing of detected candidates (5 genes) in an additional 93 patients.15 Excluding PIGA mutations, somatic mutations were detected in 29 of 150 (19.3%) patients. In accordance with Yoshizato et al’s report, mutations were more frequently observed in older patients and in those having longer (>6 months) disease durations. Allelic burdens were generally small, particularly in patients with shorter disease duration.

Characteristics of mutations in AA

Yoshizato et al also interrogated non-MDS/AML-related mutations by whole exome sequencing (WES) in 52 patients, including 15 with no detectable mutations in targeted sequencing. Four of the 15 patients were newly found to carry 5 mutations that involved very large genes, likely representing somatic mosaicism in blood reported in ∼10% of the human population.19 No other genes than MDS/AML-related genes were recurrently mutated, suggesting that the latter genes should be the major driver targets in AA.

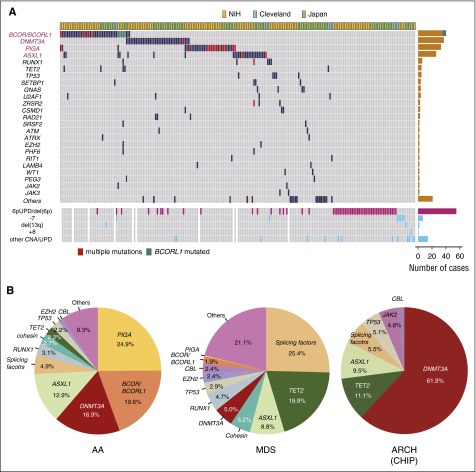

Mutations most frequently affected 5 genes, including PIGA, BCOR/BCORL1, DNMT3A, and ASXL1. Other MDS/AML-related genes were also recurrently mutated but at lower frequencies (Figure 3).18,20,66 The highly recurrent nature of well-characterized driver mutations indicates that they were selected by a Darwinian mechanism, rather than stochastically achieving a clonal dominance merely by a rapid expansion from a small number of residual stem cells (“bottleneck”).9 In several patients, some of these genes, including PIGA, DNMT3A, ASXL1, BOCR, and RUNX1, harbor multiple, independent mutations, suggesting a strong selective pressure favoring evolution of cells having these mutations (Figure 3A).18

Figure 3.

Genetic alterations in AA. (A) Somatic mutations and other genetic lesions in AA. Mutations and CNAs indicated on the left are shown for individual patients (shown horizontally). Frequency of each genetic lesion is presented on the right. (B) Frequency of mutations in AA, MDS, and ARCH, according to the reports from Yoshizato et al,18 Haferlach et al,66 and Jaiswal et al,20 respectively, for which the denominators are the total numbers of mutations in each report. ARCH, age-related CH; CHIP, CH with indeterminate potential; NIH, National Institutes of Health.

Whereas DNMT3A and ASXL1 are among common mutational targets in both AA and MDS/AML, there was a substantial overrepresentation of PIGA and BCOR/BCORL1 mutations and underrepresentation of mutations in TET2, TP53, RUNX1, cohesion, and splicing factors in AA compared with MDS/AML, most likely reflecting the difference in the mechanism of clonal selection between both diseases and/or between mutations (Figure 3B). In accordance with this, mutations exhibit different temporal behavior, age dependency, impacts on disease progression, overall survival, and response to IST. DNMT3A and ASXL1 mutations tend to increase their clone size over years, whereas BCOR/BCORL1 and PIGA mutations are likely to show a decreasing or stable clone size. Generally, frequency and the mean number of mutations increase with age, which is not the case for the latter set of mutations. As a whole, mutations do not significantly affect response to IST, progression to MDS/AML, or overall survival. However, when analyzed separately, mutations in DNMT3A, ASXL1, TP53, RUNX1, and CSMD1 (“unfavorable” mutations) are significantly associated with faster progression to MDS/AML, shorter overall survival, and poor response to IST compared with PIGA and BCOR/BCORL1 mutations (“favorable” mutations) (∼40% vs 3% of projected progression to MDS/AML and 60% vs ∼20% projected mortality for unfavorable vs favorable mutations, respectively). Kulasekararaj et al also reported a significant association of mutations with faster progression to MDS (38% for mutated vs 6% for unmutated cases, P < .01), particularly for patients with longer disease durations and larger clone size, although the small cohort size seemed to prevent the analysis of the differential effect of mutations.15

Dynamics of clones

Yoshizato et al illustrated the dynamics of clonal evolution found in AA patients by combining WES and accurate determination of allelic burden of detected mutations in 28 patients at multiple time points (2-14; median, 5) along their clinical course over a median of 5 years (range, 1-12 years).18 In the majority of cases, clones kept their small clone size over years. However, in other patients who progressed to MDS/AML, the size of dominant clones invariably increased over time. Evolution of new clones was quite common, often accompanied by complete sweeping of preexisting clones. Nevertheless, an increasing clone size did not necessarily herald MDS/AML progression but was compatible with completely normal peripheral blood counts, even when patients’ hematopoiesis was mostly supported by these clones. Even in the patients who eventually developed MDS/AML, the dominance of clones having typical MDS/AML-related mutations persisted for years without the diagnosis of MDS/AML.

Age-related CH in the general population

Notably, CH is also found in the general population. It was originally suggested by the studies on NRXI53,54 and has recently been investigated more extensively using advanced genomics. By reanalyzing SNP array data generated for >50 000 individuals who did not carry hematologic cancer, Jacobs et al43 and Laurie et al44 demonstrated that CNAs and UPDs were observed at increasing frequencies in peripheral blood from elderly people (∼2% to 3%) compared with those from younger people (∼<0.5%) (ARCH). Some authors describe the same phenomenon under the term “CHIP” (CH with indeterminate potential), although the potential may not be totally indeterminate. The most frequent lesions include del(20q), del(11q), del(13q), and UPDs in 4q, 11q, 13q, and 14q, which are common in myeloid malignancies.41,67-70 Importantly, ARCH is shown to be associated with a substantially high incidence of developing hematologic cancer (hazard ratio,10-35.4).19,20,43,44

Busque et al reported TET2 mutations in PNMs (not in lymphoid cells) from 10 of 182 (5.6%) elderly women (>65 years old) with NRXI, but not in 95 younger women (<60 years old) or 105 elderly women without NRXI.71 More comprehensive surveys of leukemia/MDS-associated mutations in the general population were conducted by repurposing WES data of peripheral blood DNA from large population-based studies. Jaiswal et al focused on 160 candidate mutational targets reported in hematologic cancers and found mutations in 73 genes in 746 of 17 182 participants.20 Genovese et al, by contrast, analyzed somatic mutations in 12 380 participants in an unbiased fashion, by evaluating those variants present only in a subfraction of cells. They found a total of 1918 participants having at least 1 putative somatic mutation, of which 308 individuals carrying known cancer-associated driver mutations and 195 others who had no putative drivers but had ≥3 somatic mutations were considered to have CH.19 In agreement with studies on CNAs, the frequency of CH in both studies increased with age (∼1% in those <50 years old vs ∼10% in those >65 years old) and, as with CH in AA, it was dominated by age-related C to T transitions. A similar finding was reported using whole exome data of cancer-bearing patients with no evidence of hematologic cancer.21 Given the limitation of WES to capture mutations with low allelic burdens, the incidence should be even higher when mutations are detected by deep sequencing.68 Strikingly, recurrent mutations were highly biased to common driver genes implicated in myeloid malignancies and most frequently affected DNMT3A, followed by TET2, ASXL1, TP53, SF3B1, JAK2, and SRSF2, which differed substantially from the case with AA (Figure 3B); in AA, PIGA and BCOR/BCORL1 were more frequently mutated than DNMT3A and ASXL1, whereas mutations in TET2, TP53, SF3B1, JAK2, and SRSF2 were infrequent. As is the case with ARCH associated with CNAs, individuals carrying mutations have a higher risk for developing hematologic cancer (hazard ratio, 11.1-12.9) and all-cause mortality, compared to individuals without CH.19,20

Mechanisms of CH in AA

CH is highly prevalent among patients with AA (∼50%), in which 2 types of genetic alterations seem to be involved in the clonal selection, although both are not necessarily mutually exclusive (Table 2): (1) mutations and CNAs commonly seen in MDS/AML (eg, −7, DNMT3A, ASXL1, and other mutations) and (2) those highly specific to or overrepresented in AA (PIGA/BOCR/BCORL1 mutations and 6pUPD). The 2 types of alterations show different chronological behaviors, age distribution, impacts on response to IST, progression to MDS/AML, and overall survival, suggesting discrete mechanisms of clonal selection.

Table 2.

CH in AA and the general population

| Aplastic anemia | Normal individuals | MDS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mutations | High (>50%) | Low (∼2%) | Very high (∼90%)* |

| Correlation to age | Positive | Positive | Positive |

| Mutated <40 y, % | 20-40 | <1 | |

| Mutated >70 y, % | 52 | >10 | |

| Signature | Age-related C to T transitions | Age-related C to T transitions | Age-related C to T transitions |

| Commonly mutated genes | BCOR/BCORL1, PIGA, DNMT3A, ASXL1 | DNMT3A, TET2, ASXL1, JAK2, TP53, SF3B1 | TET2, SF3B1, ASXL1, SRSF2, DNMT3A, RUNX1, TP53 |

| Variant allele frequency | Low (generally <10%) | Low (generally <10%) | High (>30%) |

| Copy number variations, % | ∼20 | <2 | ∼50 |

| Cytogenetics SNP array karyotyping | UPD in 6p | del(20q) | −5/del(5q) |

| −7/del(7q) | del(13q) | −7/del(7q) | |

| +6 | del(11q) | +8 | |

| +8 | 17pLOH | 17pLOH | |

| +15 | UPD in 4q, 9p, 11q, 14q | del(20q) | |

| del(13q) | UPDs in 4q, 11q, 13q, 14q | ||

| Impact of CH on progression to MDS/AML | ∼3% for BCOR, BCORL1, and PIGA mutations | Relative risk: ∼10× to ∼35× | |

| ∼40% for DNMT3A, ASXL1, RUNX1, TP53, and CSMD2 mutations |

By abnormal cytogenetic and somatic mutations.

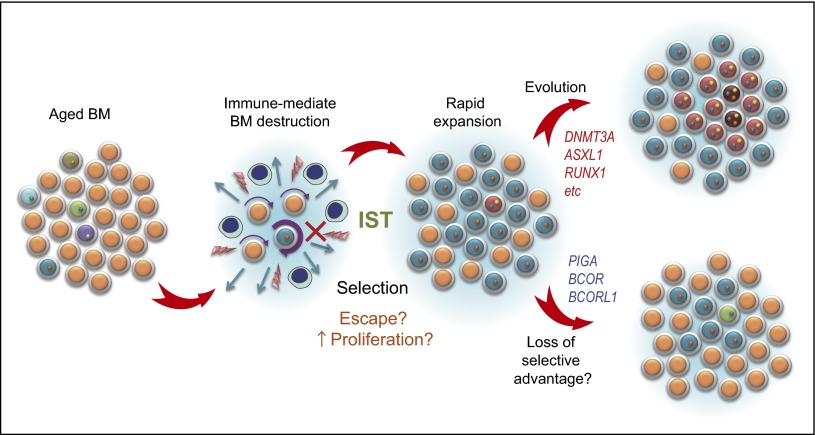

MDS/AML-related mutations in AA show a clear age dependency and are dominated by C to T transitions,18 as also seen in ARCH,19,20 suggesting that these mutations could have a common origin, randomly acquired with aging (Figure 4).72 Given their tight association with MDS/AML, it might be postulated that these mutations are clonally selected in AA and in the general population through a similar mechanism that would operate in the development of MDS/AML. In fact, in those AA patients who developed MDS/AML, an initial clone having 1 or more MDS/AML-related mutations gradually expanded and eventually gave rise to MDS/AML,18 although not all patients carrying those mutations progressed to MDS/AML. However, despite frequent DNMT3A and ASXL1 mutations in AA and MDS/AML, relative frequencies of other MDS/AML-related mutations differ substantially between both conditions; for example, TET2, JAK2, and splicing factors represent common targets of mutations in ARCH but are affected at lower frequencies in AA (Figure 3B). In contrast to the very high rate of progression to MDS/AML among AA patients with unfavorable mutations, the absolute risk of ARCH for MDS/AML progression still remained modest (∼0.5% to 1% per year) (Table 2).73 A possible explanation would be that in AA, BM is repopulated from a small number of residual stem cells after IST, which could provide clones having a proliferative advantage with a higher chance of cell cycling to achieve clonal dominance (bottleneck effects), compared with the case of ARCH in a normally populated BM environment (Figure 4).9 Alternatively, the autoimmune environment can preferentially select DNMT3A and ASXL1 mutations over others.

Figure 4.

A possible model for clonal evolution in AA. Upon immune-mediated destruction of BM, some clones are thought to be resistant to the inciting autoimmune insult and/or show faster cycling/less apoptosis than others upon BM recovery to achieve a clonal dominance. In some cases, the dominant clones, especially those having DNMT3A, ASXL1, and other unfavorable mutations, increase their clone size, giving rise to more selectively dominant clones therein. In other cases, typically those carrying PIGA mutations (and possibly BCOR/BCOR mutations), initially dominant clones may regress or remain stable over years.

Immune escape as the mechanism for CH

The other set of lesions, including 6pUPD and PIGA mutations, are highly specific to AA, for which autoimmunity has been implicated in the mechanisms of clonal selection (“clonality as escape”) (Figure 4), as first proposed by Young et al.5 6pUPD represents the most frequent genetic lesion in AA.18,63 All 6pUPDs critically involve the class I HLA locus proximally, leading to uniparental expression of the retained HLA class I alleles.63 Significantly, most of the patients (36/40) with 6pUPD carry 1 or more of 4 HLA alleles (A*02:01, A*02:06, A*31:01, and B*40:02), which are significantly enriched in AA (and also in PNH74) patients compared with the general population, and are the alleles consistently lost in UPD-positive clones.63 These observations would lead to a hypothesis that unknown causative antigens are presented to cytotoxic T cells via these class I HLAs, loss of which in 6pUPD-positive HSCs enables escape from cytotoxic T cell–mediated destruction (Figure 5). A similar mechanism seems to operate in leukemic relapse after haploidentical transplantation, in which relapsed leukemic cells are thought to escape alloimmunity by losing the mismatched haploid alleles via 6pUPD.75,76

Figure 5.

Putative mechanism of immune escape of 6pUPD-positive clones. (A) A schematic diagram of 6pUPD, which is thought to result from a recombination between 2 homologous chromosomes, invariably involving 6pter distally. (B) Breakpoint mapping of 6pUPD in different patients, showing a prominent breakpoint cluster within the HLA class I region. Breakpoints in critical cases are shown by arrows. (C) 6pUPD-positive (+) HSCs permanently lose the relevant HLA class I molecule required for the presentation of the putative antigen and are thereby thought to escape destruction by CTLs. The 6pUPD-mediated mechanism for immune escape in AA is also supported by the presence of multiple independent 6pUPD clones affecting the same parental HLA allele in some patients.63

A conspicuous correlation between AA and the PNH-type cells, together with the frequent presence of multiple PIGA-mutated clones in 10% to 30% of AA/PNH patients,15,18,77,78 indicates a strong selective advantage of PIGA-mutated cells that would be sufficient for clonal expansion of PNH-type cells within BM in AA patients,79,80 although there is no direct experimental evidence supporting this hypothesis. Nevertheless, this does not necessarily exclude a possible role of secondary mutations in clonal selection of PIGA-mutated cells, which has long been discussed. Variious plausible secondary driver alterations have been reported in occasional cases and implicated in the clonal outgrowth of PIGA-mutated clones, including those affecting HMGA2, NRAS, JAK2, TET2, U2AF1, and even BCR/ABL.78,81-84 However, thus far, no consistently recurrent mutational targets have been identified, even with WES,78 precluding the indispensable role of these secondary mutations in the development of PNH.

Currently, the underlying molecular mechanism for immune escape of PIGA-mutated cells in AA is poorly understood. A possible mechanism would include loss of expression of GPI-anchored proteins critical for immune recognitions.79,80 PIGA-mutated clones rarely disappear but, more often, persist, even after successful IST, which is in agreement with the theory of natural selection in the population genetics; many functional variants selected against past, but not present, insults are widely observed among the human population.85 Frequent genetic drifts displayed by PNH-type clones18,86,87 also seem to favor the explanation.

Clinical implications of somatic mutations

In the light of these new findings on CH in AA, as well as in the general population, an important question would be, How could we translate them into better clinical practice and improved outcome of patients? An extremely elevated risk of MDS/AML progression and high mortality rates associated with unfavorable mutations would reasonably raise a possibility of early intervention with allogeneic stem cell transplant for AA patients with unfavorable mutations, which should be best investigated in a setting of prospective trials.88 Also, the current WHO criteria for MDS could be extended for those patients having a set of unfavorable mutations on the basis of their impact on clinical/biological outcomes (Figure 6A), which is exactly the same way the current cytogenetic criteria have been included.

Figure 6.

Clonality and MDS diagnosis in AA and other refractory cytopenia. (A) Clonality (orange) is common (>50%) in AA when assessed by gene mutations and other genetic lesions, such as cytogenetic abnormalities, using advanced genomics. However, the clonal evolution does not necessarily mean the development of diseases, especially malignant ones, such as MDS. According to the current World Health Organization (WHO) criteria, patients with AA are diagnosed as having MDS when cytopenia is present and clonality is evidenced by MDS-specific cytogenetic abnormalities, such as monosomy 7, even in the absence of dysplasia or increased blast counts (pink circle). Their clone size is not relevant as long as they are found at ≥2 metaphases. On the other hand, not all clonality is associated with MDS diagnosis (and vice versa). For example, isolated abnormalities of trisomy 8, del(20q), and –Y, are not considered to be sufficient evidence of MDS diagnosis without morphological evidence or increased blast counts, because these isolated lesions may be found in normal individuals and do not likely to correlate with typical MDS pictures. Similarly, without other evidence of MDS, somatic mutations, including those affecting common targets of myeloid malignancies, are not thought to be evidence of malignant clonal evolution by themselves. In fact, in many AA cases, somatic mutations or other clonality can be compatible with normal or almost normal blood counts. By contrast, patients with unfavorable mutations (blue circle) are more likely to show poor prognosis and to satisfy the WHO criteria for MDS/AML during their clinical course than patients with other mutations. (B) A parallel relationship is also found in unexplained cytopenia in the general population. According to the WHO criteria, the clonality (cytogenetic) criteria of MDS are reserved for MDS-specific lesions, which suffice for the diagnosis of MDS, even without evidence of dysplasia or increased blast counts. Those patients with unexplained refractory cytopenia having no evidence of MDS (between red and blue circles) are designated as ICUS. Some ICUS patients show evidence of clonal evolution (CCUS), and recent reports have suggested some similarity between CCUS and MDS (see main text), for which further confirmation is needed. CCUS, clonal ICUS.

Of interest in this regard are 2 recent studies on somatic mutations among ICUS patients, because these patients also had persistent cytopenia with no definitive evidence of MDS. Kwok et al reported that a substantial fraction of ICUS patients harbored similar MDS/AML-related mutations showing comparable allelic burdens to those found in low-risk MDS.89 Cargo et al, on the other hand, investigated prediagnostic samples from ICUS patients who eventually progressed to MDS/AML and observed a high frequency of MDS/AML-related mutations comparable to those found in MDS patients in their number and variant allele frequency.90 These findings might also suggest a possibility that these ICUS patients with MDS/AML-related mutations (or clonal cytopenias of undetermined significance73,89) could be better considered as having MDS or pre-MDS (Figure 6B). Lastly, it cannot be more underscored that regardless of the definition of MDS, careful examination of patients for hematologic status/morphology, symptoms, and clinical course, as well as detailed history taking, should constitute the indispensable basis for a pertinent utilization of these new findings for better management of AA patients and other individuals presented with unexplained cytopenia.

Concluding remarks

Recent advances in high-throughput sequencing technologies have revealed an unexpected complexity of CH in AA, which is closely related to, but in several respects distinct from, CH found in the aged normal population, in which immune-mediated BM destruction and subsequent recovery in AA seem to play a critical role. CH is common in AA, in which clones may eventually proceed to malignant transformation in some cases, but in others, may continue to support apparently normal hematopoiesis. Mutation types can predict the behavior of clones and patients’ clinical course to some extent, but is not totally predictable, suggesting a potential value of monitoring CH using NGS now widely available. Understanding of the mechanism underlying clonal selection of different mutations should help in the accurate diagnosis/prediction of malignant evolution and in better management of AA patients.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Tetsuichi Yoshizato and Neal S. Young for helpful discussions on CH in AA.

This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid from the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare of Japan (Health and Labor Sciences Research Expenses for Commission and Applied Research for Innovative Treatment of Cancer).

Authorship

Contribution: S.O. conceived this review article, analyzed the literature, wrote the manuscript, and prepared the illustrations.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Seishi Ogawa, Department of Pathology and Tumor Biology, Graduate School of Medicine, Kyoto University, Yoshida-Konoe-cho, Sakyo-ku, Kyoto 606-8501, Japan; e-mail: sogawa-tky@umin.ac.jp.

References

- 1.Risitano AM, Maciejewski JP, Green S, Plasilova M, Zeng W, Young NS. In-vivo dominant immune responses in aplastic anaemia: molecular tracking of putatively pathogenetic T-cell clones by TCR beta-CDR3 sequencing. Lancet. 2004;364(9431):355–364. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16724-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zeng W, Maciejewski JP, Chen G, Young NS. Limited heterogeneity of T cell receptor BV usage in aplastic anemia. J Clin Invest. 2001;108(5):765–773. doi: 10.1172/JCI12687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zeng W, Nakao S, Takamatsu H, et al. Characterization of T-cell repertoire of the bone marrow in immune-mediated aplastic anemia: evidence for the involvement of antigen-driven T-cell response in cyclosporine-dependent aplastic anemia. Blood. 1999;93(9):3008–3016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sloand E, Kim S, Maciejewski JP, Tisdale J, Follmann D, Young NS. Intracellular interferon-gamma in circulating and marrow T cells detected by flow cytometry and the response to immunosuppressive therapy in patients with aplastic anemia. Blood. 2002;100(4):1185–1191. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-01-0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Young NS, Calado RT, Scheinberg P. Current concepts in the pathophysiology and treatment of aplastic anemia. Blood. 2006;108(8):2509–2519. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-03-010777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marsh JC, Ball SE, Cavenagh J, et al. British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of aplastic anaemia. Br J Haematol. 2009;147(1):43–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marsh JC, Geary CG. Is aplastic anaemia a pre-leukaemic disorder? Br J Haematol. 1991;77(4):447–452. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1991.tb08608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Socié G, Rosenfeld S, Frickhofen N, Gluckman E, Tichelli A. Late clonal diseases of treated aplastic anemia. Semin Hematol. 2000;37(1):91–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Young NS. The problem of clonality in aplastic anemia: Dr Dameshek’s riddle, restated. Blood. 1992;79(6):1385–1392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abkowitz JL. Clone wars--the emergence of neoplastic blood-cell clones with aging. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(26):2523–2525. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1412902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martincorena I, Campbell PJ. Somatic mutation in cancer and normal cells. Science. 2015;349(6255):1483–1489. doi: 10.1126/science.aab4082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dameshek W. Riddle: what do aplastic anemia, paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) and “hypoplastic” leukemia have in common? Blood. 1967;30(2):251–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lane AA, Odejide O, Kopp N, et al. Low frequency clonal mutations recoverable by deep sequencing in patients with aplastic anemia. Leukemia. 2013;27(4):968–971. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heuser M, Schlarmann C, Dobbernack V, et al. Genetic characterization of acquired aplastic anemia by targeted sequencing. Haematologica. 2014;99(9):e165–e167. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2013.101642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kulasekararaj AG, Jiang J, Smith AE, et al. Somatic mutations identify a subgroup of aplastic anemia patients who progress to myelodysplastic syndrome. Blood. 2014;124(17):2698–2704. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-05-574889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Babushok DV, Perdigones N, Perin JC, et al. Emergence of clonal hematopoiesis in the majority of patients with acquired aplastic anemia. Cancer Genet. 2015;208(4):115–128. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergen.2015.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang J, Ge M, Lu S, et al. Mutations of ASXL1 and TET2 in aplastic anemia. Haematologica. 2015;100(5):e172–e175. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2014.120931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoshizato T, Dumitriu B, Hosokawa K, et al. Somatic mutations and clonal hematopoiesis in aplastic anemia. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(1):35–47. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Genovese G, Kähler AK, Handsaker RE, et al. Clonal hematopoiesis and blood-cancer risk inferred from blood DNA sequence. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(26):2477–2487. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1409405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jaiswal S, Fontanillas P, Flannick J, et al. Age-related clonal hematopoiesis associated with adverse outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(26):2488–2498. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1408617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xie M, Lu C, Wang J, et al. Age-related mutations associated with clonal hematopoietic expansion and malignancies. Nat Med. 2014;20(12):1472–1478. doi: 10.1038/nm.3733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shlush LI, Zandi S, Mitchell A, et al. HALT Pan-Leukemia Gene Panel Consortium. Identification of pre-leukaemic haematopoietic stem cells in acute leukaemia. Nature. 2014;506(7488):328–333. doi: 10.1038/nature13038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Damm F, Mylonas E, Cosson A, et al. Acquired initiating mutations in early hematopoietic cells of CLL patients. Cancer Discov. 2014;4(9):1088–1101. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-0104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sakata-Yanagimoto M, Enami T, Yoshida K, et al. Somatic RHOA mutation in angioimmunoblastic T cell lymphoma. Nat Genet. 2014;46(2):171–175. doi: 10.1038/ng.2872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chung SS, Kim E, Park JH, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell origin of BRAFV600E mutations in hairy cell leukemia. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(238):238ra71. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Najean Y, Haguenauer O The Cooperative Group for the Study of Aplastic and Refractory Anemias. Long-term (5 to 20 years) evolution of nongrafted aplastic anemias. Blood. 1990;76(11):2222–2228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hillmen P, Lewis SM, Bessler M, Luzzatto L, Dacie JV. Natural history of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(19):1253–1259. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199511093331904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Latour RP, Mary JY, Salanoubat C, et al. French Society of Hematology; French Association of Young Hematologists. Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria: natural history of disease subcategories. Blood. 2008;112(8):3099–3106. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-133918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Socié G, Mary JY, de Gramont A, et al. French Society of Haematology. Paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria: long-term follow-up and prognostic factors. Lancet. 1996;348(9027):573–577. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)12360-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Planque MM, Bacigalupo A, Würsch A, et al. Severe Aplastic Anaemia Working Party of the European Cooperative Group for Bone Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) Long-term follow-up of severe aplastic anaemia patients treated with antithymocyte globulin. Br J Haematol. 1989;73(1):121–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1989.tb00230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frickhofen N, Heimpel H, Kaltwasser JP, Schrezenmeier H German Aplastic Anemia Study Group. Antithymocyte globulin with or without cyclosporin A: 11-year follow-up of a randomized trial comparing treatments of aplastic anemia. Blood. 2003;101(4):1236–1242. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosenfeld S, Follmann D, Nunez O, Young NS. Antithymocyte globulin and cyclosporine for severe aplastic anemia: association between hematologic response and long-term outcome. JAMA. 2003;289(9):1130–1135. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.9.1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tichelli A, Gratwohl A, Nissen C, Speck B. Late clonal complications in severe aplastic anemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 1994;12(3-4):167–175. doi: 10.3109/10428199409059587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tichelli A, Gratwohl A, Würsch A, Nissen C, Speck B. Late haematological complications in severe aplastic anaemia. Br J Haematol. 1988;69(3):413–418. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1988.tb02382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tichelli A, Schrezenmeier H, Socié G, et al. A randomized controlled study in patients with newly diagnosed severe aplastic anemia receiving antithymocyte globulin (ATG), cyclosporine, with or without G-CSF: a study of the SAA Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Blood. 2011;117(17):4434–4441. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-08-304071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brodsky RA, Mukhina GL, Li S, et al. Improved detection and characterization of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria using fluorescent aerolysin. Am J Clin Pathol. 2000;114(3):459–466. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/114.3.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brodsky RA, Mukhina GL, Nelson KL, Lawrence TS, Jones RJ, Buckley JT. Resistance of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria cells to the glycosylphosphatidylinositol-binding toxin aerolysin. Blood. 1999;93(5):1749–1756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li Y, Li X, Ge M, et al. Long-term follow-up of clonal evolutions in 802 aplastic anemia patients: a single-center experience. Ann Hematol. 2011;90(5):529–537. doi: 10.1007/s00277-010-1140-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Socié G, Henry-Amar M, Bacigalupo A, et al. European Bone Marrow Transplantation-Severe Aplastic Anaemia Working Party. Malignant tumors occurring after treatment of aplastic anemia. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(16):1152–1157. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199310143291603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kojima S, Ohara A, Tsuchida M, et al. Japan Childhood Aplastic Anemia Study Group. Risk factors for evolution of acquired aplastic anemia into myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia after immunosuppressive therapy in children. Blood. 2002;100(3):786–790. doi: 10.1182/blood.v100.3.786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brunning R, Orazi A, Germing U, et al. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2008. Myelodysplastic Syndromes. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cazzola M, Della Porta MG, Malcovati L. The genetic basis of myelodysplasia and its clinical relevance. Blood. 2013;122(25):4021–4034. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-09-381665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jacobs KB, Yeager M, Zhou W, et al. Detectable clonal mosaicism and its relationship to aging and cancer. Nat Genet. 2012;44(6):651–658. doi: 10.1038/ng.2270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Laurie CC, Laurie CA, Rice K, et al. Detectable clonal mosaicism from birth to old age and its relationship to cancer. Nat Genet. 2012;44(6):642–650. doi: 10.1038/ng.2271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wimazal F, Fonatsch C, Thalhammer R, et al. Idiopathic cytopenia of undetermined significance (ICUS) versus low risk MDS: the diagnostic interface. Leuk Res. 2007;31(11):1461–1468. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2007.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Valent P, Bain BJ, Bennett JM, et al. Idiopathic cytopenia of undetermined significance (ICUS) and idiopathic dysplasia of uncertain significance (IDUS), and their distinction from low risk MDS. Leuk Res. 2012;36(1):1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2011.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tichelli A, Gratwohl A, Nissen C, Signer E, Stebler Gysi C, Speck B. Morphology in patients with severe aplastic anemia treated with antilymphocyte globulin. Blood. 1992;80(2):337–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bennett JM, Orazi A. Diagnostic criteria to distinguish hypocellular acute myeloid leukemia from hypocellular myelodysplastic syndromes and aplastic anemia: recommendations for a standardized approach. Haematologica. 2009;94(2):264–268. doi: 10.3324/haematol.13755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Busque L, Gilliland DG. X-inactivation analysis in the 1990s: promise and potential problems. Leukemia. 1998;12(2):128–135. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2400936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.van Kamp H, Landegent JE, Jansen RP, Willemze R, Fibbe WE. Clonal hematopoiesis in patients with acquired aplastic anemia. Blood. 1991;78(12):3209–3214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ohashi H. Clonality in refractory anemia [in Japanese]. Rinsho Ketsueki. 1993;34(3):265–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mortazavi Y, Chopra R, Gordon-Smith EC, Rutherford TR. Clonal patterns of X-chromosome inactivation in female patients with aplastic anaemia studies using a novel reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction method. Eur J Haematol. 2000;64(6):385–395. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0609.2000.90150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fey MF, Liechti-Gallati S, von Rohr A, et al. Clonality and X-inactivation patterns in hematopoietic cell populations detected by the highly informative M27 beta DNA probe. Blood. 1994;83(4):931–938. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Busque L, Mio R, Mattioli J, et al. Nonrandom X-inactivation patterns in normal females: lyonization ratios vary with age. Blood. 1996;88(1):59–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Appelbaum FR, Barrall J, Storb R, et al. Clonal cytogenetic abnormalities in patients with otherwise typical aplastic anemia. Exp Hematol. 1987;15(11):1134–1139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Keung YK, Pettenati MJ, Cruz JM, Powell BL, Woodruff RD, Buss DH. Bone marrow cytogenetic abnormalities of aplastic anemia. Am J Hematol. 2001;66(3):167–171. doi: 10.1002/1096-8652(200103)66:3<167::aid-ajh1040>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Maciejewski JP, Risitano A, Sloand EM, Nunez O, Young NS. Distinct clinical outcomes for cytogenetic abnormalities evolving from aplastic anemia. Blood. 2002;99(9):3129–3135. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.9.3129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mikhailova N, Sessarego M, Fugazza G, et al. Cytogenetic abnormalities in patients with severe aplastic anemia. Haematologica. 1996;81(5):418–422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Holbro A, Jotterand M, Passweg JR, Buser A, Tichelli A, Rovó A. Comment to “Favorable outcome of patients who have 13q deletion: a suggestion for revision of the WHO ‘MDS-U’ designation” Haematologica. 2012;97(12):1845-9. Haematologica. 2013;98(4):e46–e47. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2012.082875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hosokawa K, Katagiri T, Sugimori N, et al. Favorable outcome of patients who have 13q deletion: a suggestion for revision of the WHO ‘MDS-U’ designation. Haematologica. 2012;97(12):1845–1849. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.061127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Saitoh T, Saiki M, Kumagai T, Kura Y, Sawada U, Horie T. Spontaneous clinical and cytogenetic remission of aplastic anemia in a patient with del(13q). Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2002;136(2):126–128. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(02)00519-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Afable MG, II, Wlodarski M, Makishima H, et al. SNP array-based karyotyping: differences and similarities between aplastic anemia and hypocellular myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood. 2011;117(25):6876–6884. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-11-314393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Katagiri T, Sato-Otsubo A, Kashiwase K, et al. Japan Marrow Donor Program. Frequent loss of HLA alleles associated with copy number-neutral 6pLOH in acquired aplastic anemia. Blood. 2011;118(25):6601–6609. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-07-365189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vogelstein B, Papadopoulos N, Velculescu VE, Zhou S, Diaz LA, Jr, Kinzler KW. Cancer genome landscapes. Science. 2013;339(6127):1546–1558. doi: 10.1126/science.1235122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Alexandrov LB, Nik-Zainal S, Wedge DC, et al. Australian Pancreatic Cancer Genome Initiative; ICGC Breast Cancer Consortium; ICGC MMML-Seq Consortium; ICGC PedBrain. Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature. 2013;500(7463):415–421. doi: 10.1038/nature12477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Haferlach T, Nagata Y, Grossmann V, et al. Landscape of genetic lesions in 944 patients with myelodysplastic syndromes. Leukemia. 2014;28(2):241–247. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.James C, Ugo V, Le Couédic JP, et al. A unique clonal JAK2 mutation leading to constitutive signalling causes polycythaemia vera. Nature. 2005;434(7037):1144–1148. doi: 10.1038/nature03546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kralovics R, Passamonti F, Buser AS, et al. A gain-of-function mutation of JAK2 in myeloproliferative disorders. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(17):1779–1790. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sanada M, Suzuki T, Shih LY, et al. Gain-of-function of mutated C-CBL tumour suppressor in myeloid neoplasms. Nature. 2009;460(7257):904–908. doi: 10.1038/nature08240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chase A, Leung W, Tapper W, et al. Profound parental bias associated with chromosome 14 acquired uniparental disomy indicates targeting of an imprinted locus. Leukemia. 2015;29(10):2069–2074. doi: 10.1038/leu.2015.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Busque L, Patel JP, Figueroa ME, et al. Recurrent somatic TET2 mutations in normal elderly individuals with clonal hematopoiesis. Nat Genet. 2012;44(11):1179–1181. doi: 10.1038/ng.2413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Welch JS, Ley TJ, Link DC, et al. The origin and evolution of mutations in acute myeloid leukemia. Cell. 2012;150(2):264–278. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Steensma DP, Bejar R, Jaiswal S, et al. Clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential and its distinction from myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood. 2015;126(1):9–16. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-03-631747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shichishima T, Noji H, Ikeda K, Akutsu K, Maruyama Y. The frequency of HLA class I alleles in Japanese patients with bone marrow failure. Haematologica. 2006;91(6):856–857. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Villalobos IB, Takahashi Y, Akatsuka Y, et al. Relapse of leukemia with loss of mismatched HLA resulting from uniparental disomy after haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2010;115(15):3158–3161. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-254284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Vago L, Perna SK, Zanussi M, et al. Loss of mismatched HLA in leukemia after stem-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(5):478–488. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0811036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mortazavi Y, Merk B, McIntosh J, Marsh JC, Schrezenmeier H, Rutherford TR BIOMED II Pathophysiology and Treatment of Aplastic Anaemia Study Group. The spectrum of PIG-A gene mutations in aplastic anemia/paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (AA/PNH): a high incidence of multiple mutations and evidence of a mutational hot spot. Blood. 2003;101(7):2833–2841. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-07-2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shen W, Clemente MJ, Hosono N, et al. Deep sequencing reveals stepwise mutation acquisition in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(10):4529–4538. doi: 10.1172/JCI74747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rotoli B, Luzzatto L. Paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria. Baillieres Clin Haematol. 1989;2(1):113–138. doi: 10.1016/s0950-3536(89)80010-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Luzzatto L, Bessler M, Rotoli B. Somatic mutations in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria: a blessing in disguise? Cell. 1997;88(1):1–4. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81850-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Inoue N, Izui-Sarumaru T, Murakami Y, et al. Molecular basis of clonal expansion of hematopoiesis in 2 patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH). Blood. 2006;108(13):4232–4236. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-025148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mortazavi Y, Tooze JA, Gordon-Smith EC, Rutherford TR. N-RAS gene mutation in patients with aplastic anemia and aplastic anemia/ paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria during evolution to clonal disease. Blood. 2000;95(2):646–650. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sugimori C, Padron E, Caceres G, et al. Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria and concurrent JAK2(V617F) mutation. Blood Cancer J. 2012;2(3):e63. doi: 10.1038/bcj.2012.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Tominaga R, Katagiri T, Kataoka K, et al. Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria induced by the occurrence of BCR-ABL in a PIGA mutant hematopoietic progenitor cell. Leukemia. 2016;30(5):1208–1210. doi: 10.1038/leu.2015.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bamshad M, Wooding SP. Signatures of natural selection in the human genome. Nat Rev Genet. 2003;4(2):99–111. doi: 10.1038/nrg999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Pu JJ, Mukhina G, Wang H, Savage WJ, Brodsky RA. Natural history of paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria clones in patients presenting as aplastic anemia. Eur J Haematol. 2011;87(1):37–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2011.01615.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sugimori C, Mochizuki K, Qi Z, et al. Origin and fate of blood cells deficient in glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored protein among patients with bone marrow failure. Br J Haematol. 2009;147(1):102–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Young NS, Ogawa S. Somatic mutations and clonal hematopoiesis in aplastic anemia. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(17):1675–1676. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1509703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kwok B, Hall JM, Witte JS, et al. MDS-associated somatic mutations and clonal hematopoiesis are common in idiopathic cytopenias of undetermined significance. Blood. 2015;126(21):2355–2361. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-08-667063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Cargo CA, Rowbotham N, Evans PA, et al. Targeted sequencing identifies patients with preclinical MDS at high risk of disease progression. Blood. 2015;126(21):2362–2365. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-08-663237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]