Abstract

The function of a protein molecule is greatly influenced by its three-dimensional (3D) structure and therefore structure prediction will help identify its biological function. We have updated Sequence, Motif and Structure (SMS), the database of structurally rigid peptide fragments, by combining amino acid sequences and the corresponding 3D atomic coordinates of non-redundant (25%) and redundant (90%) protein chains available in the Protein Data Bank (PDB). SMS 2.0 provides information pertaining to the peptide fragments of length 5-14 residues. The entire dataset is divided into three categories, namely, same sequence motifs having similar, intermediate or dissimilar 3D structures. Further, options are provided to facilitate structural superposition using the program structural alignment of multiple proteins (STAMP) and the popular JAVA plug-in (Jmol) is deployed for visualization. In addition, functionalities are provided to search for the occurrences of the sequence motifs in other structural and sequence databases like PDB, Genome Database (GDB), Protein Information Resource (PIR) and Swiss-Prot. The updated database along with the search engine is available over the World Wide Web through the following URL http://cluster.physics.iisc.ernet.in/sms/.

Key words: non-redundant protein chains, sequence motifs, 3D structure, structural superposition

Introduction

One of the main concepts of molecular biology is that form and function are inseparable. The function of a protein molecule can be predicted by looking at its 3D structure. For example, a barrel-like nuclear pore (a complex of several proteins) sits in the nuclear membrane and acts as a channel through which molecules travel in or out of the nucleus (1). Similarly DNA Topoisomerase IIα – a DNA-binding enzyme, opens and closes at both ends like gates, thereby, controlling the passage of DNA strands (2). Therefore, predicting the protein structure and then comparing it with already-known structures can help pin-point its biological function. Predicting or modeling the protein structure based on its sequence and structural homologies 3, 4 or experimental data may involve a systematic search of conformational space (5), use of spatial restraints (6) and/or a database of fragments of known proteins.

The amino acid sequence, its structure, fold and structure-dependent functions can be employed for protein structure prediction. Studies by Reddy and co-workers (7) showed that for a protein to fold into a stable and functional 3D structure, only 10-20% of the sequence that contains the conserved key amino acid positions is required. A similar study carried out by another research group (8) showed persistently conserved positions in proteins with similar structure but dissimilar sequences, indicating that these positions play a significant role in preserving the protein fold. Protein structure prediction by using sequence homologies showed that penta- (9), hexa- and hepta- (10) peptides having similar sequences from different protein chains exhibited different 3D structures due to their interactions with neighboring parts of the protein molecule. Therefore, these studies illustrate the relationship and dependability of the amino acid sequences and their 3D structures.

To better understand the above and to analyze the degree to which same sequence motifs adopt same/intermediate/dissimilar 3D structures, an updated database of Sequence, Motif and Structure (SMS), SMS 2.0, was developed by considering peptide fragments of varying lengths available in non-redundant (25%) and redundant (90%) protein chains (11) derived using all the available protein structures from its archive, PDB (12). The previous version of SMS, developed by our group in the year 2006, was capable of analyzing sequence-structure relationships of peptide fragments with lengths of 5-10 residues. During superposition (using the STAMP program), the fragment from a highly resolved structure was kept as a fixed molecule and other fragments of the same sequence motifs were treated as mobile molecules. Based on the superposition results, they were further classified into three categories, namely, similar, intermediate and dissimilar 3D structures.

The present updated database addresses the structural rigidity of peptide fragments that are 5-14 amino acid residues long and occur a minimum of three times in non-redundant (25%) and redundant (90%) protein chains. The fragment database approach was first employed in 1986 when retinal binding protein was reconstructed by choosing fragments from only three proteins (13). Since then, protein fragment databases have been widely used for constructing complete protein backbone structures 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20.

Methods

SMS 2.0 is an updated comprehensive database generated using only X-ray crystallographic structures. To remove unnecessary data in the database, only non-redundant (25%) and redundant (90%) protein chains derived (resolution better than or equal to 3 Å and R-factor better than or equal to 30%) using the culled-PDB server (21) are used in the present study. The protein chains used in the dataset are very recent (July 1st, 2011). The crystal structures with only Cα coordinates were excluded from this dataset. Further, structures solved using NMR were not included in the present study. Finally, the database contains information about 7,078 and 20,261 protein chains from non-redundant (25%) and redundant (90%) datasets, respectively. Locally developed Perl scripts were used extensively to generate a dataset consisting of 1,035,715 peptide fragments of varying lengths (5-14 residues) automatically. The peptide fragments were superimposed using the program STAMP (11).

After superposition, the fragments are classified into (a) similar, (b) intermediate and (c) dissimilar 3D structures using the following procedure. Root mean square deviation (RMSD) describes the “average distance” between the atoms of superposed protein molecules. If the RMSD values (for all the possible superpositions) are all less than or equal to 1.0 Å, the fragments are placed in the similar 3D structures category. In a similar manner, if the RMSD values of all the fragments are greater than 1.0 Å, they are categorized as dissimilar 3D structures. On the other hand, if the RMSD values are a mixture of both, then they are categorized as intermediate 3D structures. The RMSD value of 1.0 Å is taken as the best optimized value because structural superposition is clearer (manual inspection) when the aforementioned value is used. Further, the value 1.0 Å is chosen carefully after several trials (superposition of more than 500 known 3D structural fragments available in the 25% non-redundant and 90% redundant protein chains) to arrive at an optimum value.

The search engine used in the database is developed using Perl/CGI scripts and the front-end user friendly input form is coded using HTML/JavaScript. The database is easy to use and has been tested on Windows and various flavors of Linux platforms through available web browsers. However, the database is expected to perform better when it is invoked using Mozilla Firefox or Safari. The above-mentioned facility is freely available over the World Wide Web (www) at the URL http://cluster.physics.iisc.ernet.in/sms/. General comments and suggestions for improvements are welcome and should be addressed to Professor K. Sekar at sekar@physics.iisc.ernet.in.

Utilities

SMS 2.0 is an updated web-based database that contains information about peptide fragments that are 5-14 residues long. Two options have been provided for users to search the peptide information. Option (a) “Peptide details”, will enable users to obtain detailed information about peptide fragments of user desired length. Using option (b) “Peptide search”, users can search for a particular peptide by entering the sequence motif (for example, AALTAL) in the text box provided. When using both options, users need to select the desired database (non-redundant [25%] or redundant [90%] dataset) and the category (one out of the three) to be searched. The classification of three categories are solely based on the structural superposition output provided by the program STAMP (11) and they include same sequence motifs having similar 3D structures, same sequence motifs having intermediate 3D structures and same sequence motifs having dissimilar 3D structures. The resultant window displays peptide fragments based on the options entered by user.

Enhanced Features

Following are the improvements in the updated database.

-

1

Only highly resolved X-ray crystallographic structures are considered in the present study.

-

2

Previous version of the database (22) had fragment information about only 25% non-redundant protein chains (a total of 2,485 protein chains), whereas the updated version has both 25% non-redundant (7,078 protein chains) and 90% redundant (20,261 protein chains) protein chains.

-

3

In the updated version, a total of 25 structural fragments (one fixed fragment and 24 mobile fragments) can be superposed at a given time. However, visualization of fewer fragments (being superposed) is clearer.

-

4

In order to essentially avoid uncertainty, the structural fragment from a well resolved structure is used as a fixed molecule during superposition. When the structural fragments are in the same polypeptide chain, the first fragment is kept as a fixed molecule.

-

5

The same sequence may adopt more than one category, for example, NMR structures have many models in which every model might differ in its conformation. Thus, in the present version, only well resolved X-ray structures are considered.

-

6

The dataset used in the updated version contains 1,035,715 peptide fragments of varying lengths (5-14 residues long) compared to 5,544 peptide fragments of lengths 5-10 residues. The increase in number of fragments is due to the inclusion of the 90% redundant dataset.

-

7

The peptide fragments are sorted and displayed in alphabetical order for all three categories.

-

8

Recently-developed fast pattern (identical and similar) matching algorithms 23, 24 are used to search for the occurrence of the fragments in other structural and sequence databases.

-

9

To visualize the 3D structure of the superposed fragment with various graphical illustrations, a freely available JAVA plug-in Jmol is introduced in the updated version compared to RasMol (in the previous version).

-

10

An option has been added in the Jmol window to view the Ramachandran angles for the superposed fragment.

Application

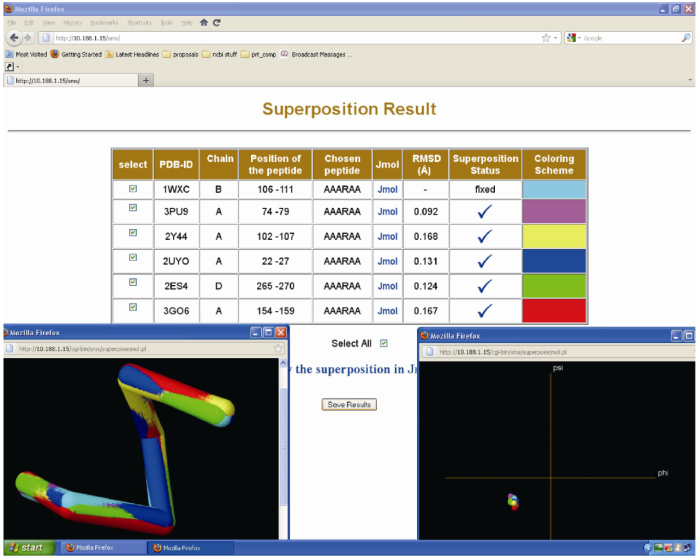

Figure 1 depicts the structural behavior of a typical hexa-peptide AAARAA which is available in 6 different protein chains of the 25% non-redundant dataset. The structural superposition of all 6 fragments, performed by STAMP, is shown in Figure 1 (Figure 1 inset, Jmol panel). The hexa-peptide (AAARAA) falls in the first category (same sequence motif having similar 3D structure). The highly resolved (1.2 Å resolution) crystal structure (1WXC) in which the hexa-peptide motif is present is treated as a fixed molecule and the remaining five fragments are treated as mobile molecules during superposition. The minimum and maximum RMSD is 0.092 Å and 0.168 Å, respectively.

Figure 1.

The structural behavior and superimposition results for a typical hexa-peptide sequence “AAARAA” occurring in 6 different 25% non-redundant protein chains. The left side graphics panel shows the superposed 3D structures of all 6 fragments. The right side graphics panel shows the Ramachandran plot for the hexa-peptide fragment.

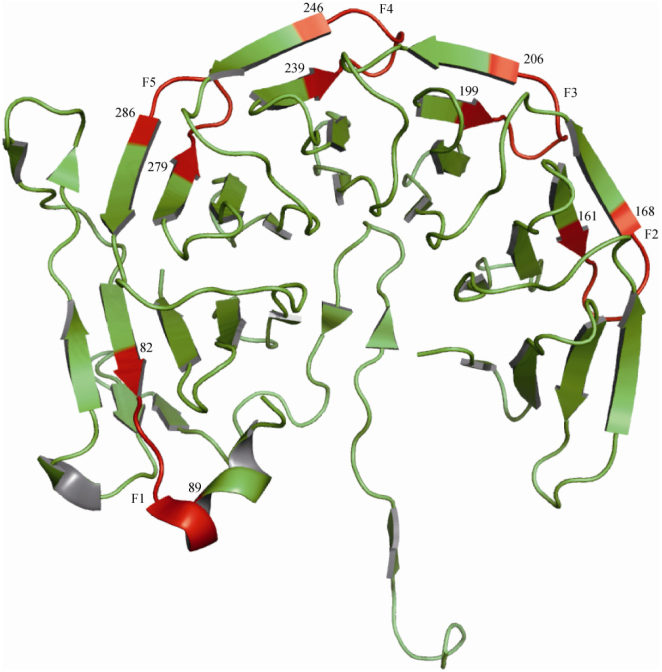

A typical example of a particular fragment is “AINPDGTE”, which occurs five times (Figure 2) in chain A of pyrrolo-quinoline quinine (3HXJ) from Methanococcus maripaludis. In the proposed database, this fragment is classified under the category “same sequence motif having intermediate 3D structures”, because the first fragment (position 82 to 89) forms an α-helix while the remaining four fragments form β-sheet. Figure 2 shows clearly that the conformation adopted by this fragment is different from the remaining four fragments. Therefore, sequence similarity does not always imply 3D structural similarity.

Figure 2.

The 3D structural disparity in the eight residue fragment “AINPDGTE”, which occurs five times in chain A (3HXJ) (F1-F5, colored in red).

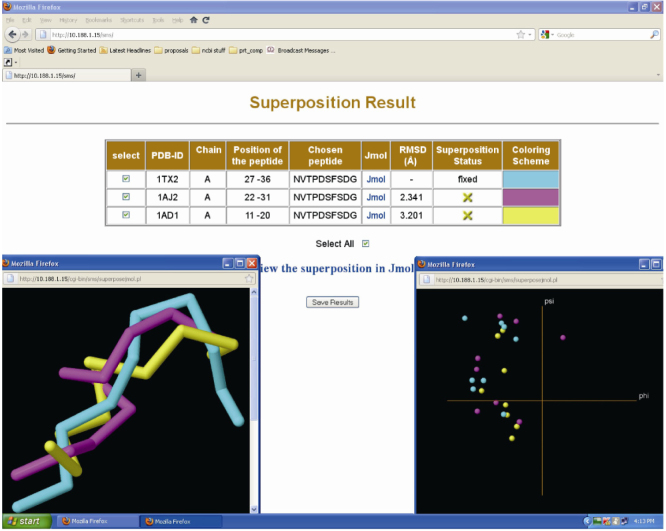

Another peptide fragment taken for the case study is the deca-peptide fragment NVTPDSFSDG which falls under the category “same sequence motif having different 3D structure”. Figure 3 shows the structural superposition results of the deca-peptide fragment occurring in three different 90% redundant protein chains. The fragment obtained from 1TX2 (1.83 Å resolution) is kept fixed and the remaining two fragments are treated as mobile molecules. Here again, the program STAMP is used for superimposing the peptide fragments. It is interesting to note that all the three fragments are from the protein molecule, “dihydropteroate synthase” from three different bacterial species (Bacillus anthracis, Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus). A quick functional domain analysis also revealed that the deca-peptide fragment is part of the pterin binding domain (results not shown).

Figure 3.

The superimposition results of a deca-peptide, NVTPDSFSDG, present in three different 90% redundant protein chains. The 3D structural superposition of all the fragments is shown using graphics panel (left panel) and their locations in the Ramachandran plot are shown in the right panel.

Conclusion

The structure of a protein molecule greatly influences its function; therefore, predicting its 3D structure will help better understand the function. The updated database (SMS 2.0) is more sophisticated with advanced features and acts as an efficient information archive (both in terms of efficiency and accuracy) compared to its previous version. It can be used to examine the degree of structural plasticity observed in short peptide fragments containing the same amino acid residues adopting similar/intermediate/dissimilar 3D structures. Thus, it is expected to aid researchers and practicing bioinformaticians in investigating the relationship between protein sequence motifs and their 3D structures.

Authors’ contributions

DR, MUK, DS and MS were involved in the creation and implementation of the database. DS and MS developed the web interface. MKV participated in discussion, curation and validation, and wrote the manuscript. KS conceived and supervised the project, critically analyzed the database and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors have declared that there are no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the facilities offered by the Bioinformatics Centre and the Interactive Graphics Facility. This work was supported by a research grant from the Department of Information Technology (DIT) awarded to KS.

References

- 1.Lodish H. W.H. Freeman & Company; New York, USA: 2000. Molecular Cell Biology Fourth Edition. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wei H. Nucleotide-dependent domain movement in the ATPase domain of a human type IIA DNA Topoisomerase. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:37041–37047. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506520200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chothia C., Lesk A.M. The relation between the divergence of sequence and structure in proteins. EMBO J. 1986;5:823–826. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04288.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lesk A.M., Chothia C. How different amino acid sequences determine similar protein structures: the structure and evolutionary dynamics of the globins. J. Mol. Biol. 1980;136:225–270. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(80)90373-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deane C.M., Blundell T.L. A novel exhaustive search algorithm for predicting the conformation of polypeptide segments in proteins. Proteins. 2000;40:135–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fiser A. Evolution and physics in comparative protein structure modeling. Acc. Chem. Res. 2002;35:413–421. doi: 10.1021/ar010061h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reddy B.V.B. CKAAPs DB: a Conserved Key Amino Acid Positions DataBase. Proteins. 2001;42:148–163. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedberg I., Margalit H. Persistently conserved positions in structurally similar, sequence dissimilar proteins: roles in preserving protein fold and function. Protein Sci. 2002;11:350–360. doi: 10.1110/ps.18602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kabsch W., Sander C. On the use of sequence homologies to predict protein structure: identical penta-peptides can have completely different conformations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1984;81:1075–1078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.4.1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilson I.A. Identical short peptide sequences in unrelated proteins can have different conformations: a testing ground for theories of immune recognition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1985;82:5255–5259. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.16.5255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Russell R.B., Barton G.J. Multiple protein sequence alignment from tertiary structure comparison: assignment of global and residue confidence levels. Proteins. 1992;14:309–323. doi: 10.1002/prot.340140216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berman H.M. The Protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:235–242. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones T.A., Thirup S. Using known substructures in protein model building and crystallography. EMBO J. 1986;5:819–822. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04287.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Claessens M. Modelling the polypeptide backbone with ‘spare parts’ from known protein structures. Protein Eng. 1989;2:335–345. doi: 10.1093/protein/2.5.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Du P. Have we seen all structures corresponding to short protein fragments in the Protein Data Bank? An update. Protein Eng. 2003;16:407–414. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzg052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Correa P.E. The building of protein structures from alpha-carbon coordinates. Proteins. 1990;7:366–377. doi: 10.1002/prot.340070408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holm L., Sander C. Database algorithm for generating protein backbone and side-chain co-ordinates from a C alpha trace application to model building and detection of co-ordinate errors. J. Mol. Biol. 1991;218:183–194. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(91)90883-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levitt M. Accurate modeling of protein conformation by automatic segment matching. J. Mol. Biol. 1992;226:507–533. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90964-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reid L.S., Thornton J.M. Rebuilding flavodoxin from C alpha coordinates: a test study. Proteins. 1989;5:170–182. doi: 10.1002/prot.340050212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Summers N.L., Karplus M. Modeling of globular proteins. A distance-based data search procedure for the construction of insertion/deletion regions and pro-nonpro mutations. J. Mol. Biol. 1990;216:991–1016. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(99)80016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang G., Dunbrack R.L., Jr. PISCES: a protein sequence culling server. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1589–1591. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Balamurugan B. SMS: Sequence, Motif and Structure - A database on the structural rigidity of peptide fragments in non-redundant proteins. In Silico Biol. 2006;6:229–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Banerjee N. An algorithm to find all identical internal sequence repeats. Curr. Sci. 2008;95:188–195. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Banerjee N. An algorithm to find similar internal sequence repeats. Curr. Sci. 2009;97:1345–1349. [Google Scholar]