Abstract

Monoclonal antibodies directed against cytotoxic T lymphocyte–associated antigen-4 (CTLA-4), such as ipilimumab, yield considerable clinical benefit for patients with metastatic melanoma by inhibiting immune checkpoint activity, but clinical predictors of response to these therapies remain incompletely characterized. To investigate the roles of tumor-specific neoantigens and alterations in the tumor microenvironment in the response to ipilimumab, we analyzed whole exomes from pretreatment melanoma tumor biopsies and matching germline tissue samples from 110 patients. For 40 of these patients, we also obtained and analyzed transcriptome data from the pretreatment tumor samples. Overall mutational load, neoantigen load, and expression of cytolytic markers in the immune microenvironment were significantly associated with clinical benefit. However, no recurrent neoantigen peptide sequences predicted responder patient populations. Thus, detailed integrated molecular characterization of large patient cohorts may be needed to identify robust determinants of response and resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Blockade of cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4), an inhibitor of T cell activation, with the monoclonal antibody ipilimumab yields improvements in overall survival in patients with metastatic melanoma as a monotherapy (1, 2) or in combination with other T cell immune checkpoint inhibitors (3, 4). Although overall single-agent response rates are low, a long-term clinical benefit is consistently observed for ~20% of treated patients (5, 6). Preclinical and clinical studies have suggested that tumor-specific missense mutations may generate individual neoantigens that mediate response to ipilimumab and other immune checkpoint inhibitors (7–10). Clinical studies of exceptional responders (11) and of small cohorts of melanoma patients have highlighted NRAS mutation status, total neoantigen load, and a neoantigen-derived tetrapeptide signature as possible correlates of response to ipilimumab in metastatic melanoma (12, 13). RNA-based studies have also identified gene expression signatures linked to immune infiltration within the tumor microenvironment that correlate with overall survival, neoantigen load (14, 15), and resistance to immunotherapy (16). To date, however, comprehensive genomic studies of tumor- and immune-related factors in larger (i.e., >100 patients) clinical cohorts have not been reported.

We hypothesized that both tumor-specific neoantigens and the tumor immune microenvironment might influence clinical benefit from ipilimumab. To test this, we performed whole-exome sequencing (WES) on a cohort of 110 patients with metastatic melanoma from whom pretreatment tumor biopsies were available for study (Fig. 1A). Tumor whole-transcriptome sequencing was performed in 42 of these patients, of whom 40 had matched WES. This cohort included 92 cutaneous, 4 mucosal, and 14 occult melanomas. After WES of matched tumor and germline samples (17), quality-control metrics were applied to ensure sensitive mutation detection (18). Average exome-wide target coverage was 183.7-fold for tumor samples and 157.2-fold for germline samples. We performed somatic mutation identification (table S1) and germline human lymphocyte antigen (HLA) typing (table S2) using established methods (14, 19). The median nonsynonymous mutational load was 197 per sample (range: 7 to 5854), which is consistent with the known high mutational loads in cutaneous melanoma (13, 20).

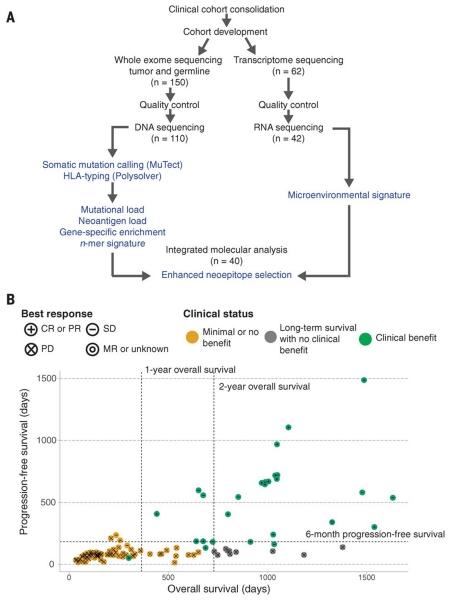

Fig. 1. Study design and clinical stratification.

(A) Patients (n = 150) were identified for whole-exome sequencing of tumor and germline DNA. To be included in the original clinical cohort, patients had to have received ipilimumab monotherapy for metastatic cutaneous melanoma, have pretreatment germline and tumor samples available for sequencing, and have had overall survival for >14 days after initiation of ipilimumab therapy. Of these patients, 110 were eventually included in analysis after exclusions due to inadequate postsequencing quality control (n = 40) (18). Manual review of raw sequencing data was performed to exclude samples with evidence suggesting low purity, high contamination by ContEst (33), or discordant copy number quality control. Of the patients, 62, including 2 who failed DNA quality-control, had FFPE tumor samples available for transcriptome sequencing. After manual review for quality control following RNA sequencing, 42 samples were also analyzed for tumor microenvironment signatures, and 40 with matched WES were analyzed for neoantigen expression (14). (B) Patients were stratified into response groups based on RECIST criteria (21) (CR, complete response; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; PD, progressive disease; MR, mixed response); duration of overall survival (OS); and duration of progression-free survival (PFS). All two-way comparisons were done comparing patients who achieved clinical benefit with ipilimumab (CR or PR by RECIST criteria or OS >1 year with SD by RECIST criteria) (n = 27) to those with minimal or no benefit from ipilimumab (PD by RECIST criteria or OS <1 year with SD by RECIST criteria) (n = 73). An additional cohort of patients who achieved long-term survival (OS >2 years) after ipilimumab treatment with early tumor progression (PFS <6 months) were considered separately (n = 10).

To stratify our cohort, “clinical benefit” was defined using a composite end point of complete response or partial response to ipilimumab by RECIST criteria (21) or stable disease by RECIST criteria with overall survival greater than 1 year (n = 27). “No clinical benefit” was defined as progressive disease by RECIST criteria or stable disease with overall survival less than 1 year (n = 73). The basis for these designations stems from clinical trials demonstrating that ipilimumab significantly improves median overall survival, with a subset of patients surviving beyond 2 years (~20%), but does not affect progression-free survival (PFS) (5, 22). A separate group of 10 patients showed early progression on ipilimumab (PFS of <6 months), but their overall survival patterns exceeded 2 years; these patients were considered as a separate patient subgroup (Fig. 1B and tables S2 and S3).

Overall, nonsynonymous mutational load was significantly associated with clinical benefit from ipilimumab (P = 0.0076; Mann-Whitney test) (Fig. 2A). This result confirms previous findings for ipilimumab in melanoma (13) and is consistent with observations regarding response to other immune checkpoint inhibitors in cancer (23, 24). Clinical metrics—such as patient age, gender, tumor histology, primary tumor site, number of therapies received before ipilimumab, and lactate dehydrogenase levels at initiation of ipilimumab monotherapy—showed no significant correlation with clinical response to ipilimumab in this cohort (P > 0.05 for all) (table S3). The subset of patients that showed long-term survival tracked with the subset that showed no clinical benefit, in terms of mutational load, but the sample size in this group was too small to draw definitive conclusions (Fig. 2A). No genes were enriched for nonsynonymous mutations, including BRAF and NRAS, in the patient subgroups that had clinical benefit or no clinical benefit (figs. S1 and S2).

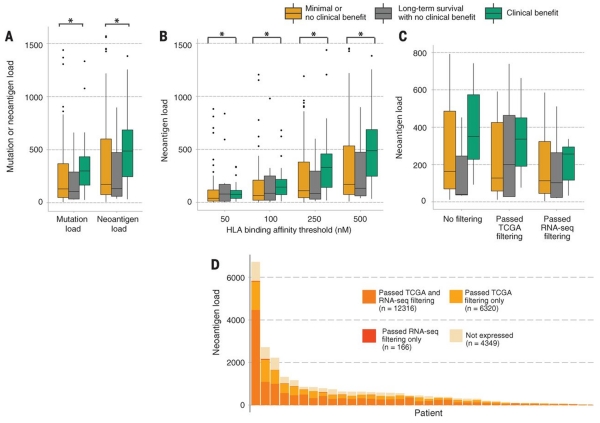

Fig. 2. Overall mutational load, overall neoantigen load, and expression-based neoantigen analysis as predictors of response to ipilimumab.

(A) Elevated nonsynonymous mutational load and neoantigen load are associated with response to ipilimumab (P = 0.0076 and 0.027, respectively). An additional 20 points are not shown because of outlying high neoantigen loads in a subset of patients. (B) No trend in increased significance was observed when comparing the burden of higher-affinity neoantigens with respect to response to ipilimumab. Lower median inhibitory concentrations imply stronger HLA binding affinity on the x axis (P = 0.027 for affinity <500 nM; P = 0.034 for affinity <250 nM; P = 0.038 for affinity <100 nM; P = 0.042 for affinity <50 nM). An additional 34 points are not shown because of outlying high neoantigen loads in a subset of patients. (C) A sample size of 40 patients with complete DNA-sequencing, RNA-sequencing, and clinical annotation was insufficient to discern significant differences in neoantigen load or expressed neoantigen load among response cohorts, but a trend was observed for increased neoantigen load among patients with clinical benefit compared with those with no clinical benefit (P > 0.05 for all). (D) Patient-specific RNA-sequencing provides distinct information on tumor gene expression compared with TCGA melanoma data from a separate patient cohort. Although TCGA and RNA-seq data agree on the expression of the majority of neoantigens (n = 12,316) for 40 patients who had high-quality DNA- and RNA-sequencing data available for neoantigen and gene expression analysis, TCGA expression data overestimate the number of neoantigens expressed by 6320 in this patient cohort, and 166 neoantigens that are expressed by patient tumors would be missed by TCGA filtering alone. Additionally, a large proportion of neoantigens (n = 4349) are expressed at negligible levels in patient tumors. Asterisks (*) indicate P < 0.05.

Next, we sought to determine the relation between neoantigen load and clinical benefit to ipilimumab. First, we identified putative immunogenic 9– and 10–amino acid neoantigens with ≤500 nM binding affinity for HLA class I molecules across the cohort, using patient-specific nonsynonymous mutations and HLA types (tables S2 and S4) (14). The median predicted neoantigen load was 369 neoantigens per sample (range: 9 to 16,300). Overall, neoantigen load was significantly associated with clinical benefit (P = 0.027; Mann-Whitney) (Fig. 2A), although high neoantigen load outliers among nonresponders and low neoantigen load outliers among responders were observed. Neoantigen load was strongly correlated with mutational load (Spearman’s rho = 0.97, P < 0.0001) as expected, given that neoantigens often arise from nonsynonymous mutations. The association between neoantigen load and clinical benefit remained significant when randomly redistributed HLA types were used to infer putative neoantigen binders (P = 0.0096; Mann-Whitney) (fig. S3).

We then sought to determine the association between aggregate neoantigen properties and clinical benefit. The correlation between neoantigen load and clinical benefit diminished when we applied increasingly stringent thresholds for affinity of binding (P = 0.034, 0.039, and 0.042 for affinity thresholds of <250 nM, 100 nM, and 50 nM, respectively; Mann-Whitney) (Fig. 2B). We also applied multivariate models that controlled for prior RAF inhibitor treatment and M class (metastasis) at start of therapy (18). These analyses confirmed that patients with high neoantigen or mutational loads (>100) were significantly more likely to have clinical benefit from ipilimumab (P = 0.0371 and P = 0.0169, respectively).

We then investigated whether any recurrent neoantigens or neoantigen epitopes might predict ipilimumab response. Of the 77,803 unique neoantigens in our cohort, 28 (~0.04%) were found in more than one patient having a clinical benefit but were absent in all patients having no clinical benefit or long-term survival (Table 1). Examination of these recurrent neoantigens did not reveal any shared features or features exclusive to responders. Previously described immunogenic nonamers identified in patients who achieved clinical benefit from immune checkpoint blockade were not observed in any patient within this cohort, including several that have undergone experimental validation (7, 11, 13, 23). Furthermore, a tetrapeptide signature (13) previously associated with ipilimumab response was not enriched in the cohort with clinical benefit relative to that with no clinical benefit (fig. S4) (25). Thus, the vast majority of clinical benefit–associated neoantigens and neoantigen epitopes identified through DNA sequencing appear to be private events without obvious recurrent features.

Table 1. Recurrent neoantigens identified exclusively in the cohort showing clinical benefit with their associated HLA types.

Variants were manually reviewed in the Integrated Genomics Viewer (34).

| Patient | Gene | HLA | Neoantigen | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pat117 | BMPER | A11:01 | CIKTCDNWNK |

| Pat123 | BMPER | A31:01 | CIKTCDNWNK | |

| 2 | Pat174 | CGB8 | C02:02 | SSSKAPLPSL |

| Pat88 | CGB2 | C16:01 | SSSKAPLPSL | |

| 3 | Pat132 | CLCN4 | C04:01 | FFATLVAAF |

| Pat132 | CLCN4 | A23:01 | FFATLVAAF | |

| Pat38 | CLCN4 | C02:02 | FFATLVAAF | |

| 4 | Pat132 | CLCN4 | C07:01 | SFFATLVAAF |

| Pat132 | CLCN4 | A23:01 | SFFATLVAAF | |

| Pat38 | CLCN4 | C07:01 | SFFATLVAAF | |

| 5 | Pat132 | CLCN4 | C07:01 | ATLVAAFTL |

| Pat138 | CLCN4 | B15:17 | ATLVAAFTL | |

| Pat38 | CLCN4 | C07:01 | ATLVAAFTL | |

| 6 | Pat132 | CLCN4 | B08:01 | TLWRSFFATL |

| Pat132 | CLCN4 | A23:01 | TLWRSFFATL | |

| Pat38 | CLCN4 | A02:01 | TLWRSFFATL | |

| 7 | Pat07 | CNTNAP5 | A01:01 | FSADIFFFF |

| Pat07 | CNTNAP5 | C07:02 | FSADIFFFF | |

| Pat07 | CNTNAP5 | C07:01 | FSADIFFFF | |

| Pat77 | CNTNAP5 | A24:02 | FSADIFFFF | |

| Pat77 | CNTNAP5 | A26:01 | FSADIFFFF | |

| Pat77 | CNTNAP5 | C12:03 | FSADIFFFF | |

| 8 | Pat07 | CNTNAP5 | B08:01 | FFFFKTTAL |

| Pat07 | CNTNAP5 | C07:02 | FFFFKTTAL | |

| Pat07 | CNTNAP5 | C07:01 | FFFFKTTAL | |

| Pat77 | CNTNAP5 | C01:02 | FFFFKTTAL | |

| Pat77 | CNTNAP5 | C12:03 | FFFFKTTAL | |

| 9 | Pat07 | CNTNAP5 | C07:02 | IFFFFKTTAL |

| Pat77 | CNTNAP5 | C12:03 | IFFFFKTTAL | |

| 10 | Pat132 | ERCC8 | A23:01 | CVFQSNFQEF |

| Pat38 | ERCC8 | C02:02 | CVFQSNFQEF | |

| Pat38 | ERCC8 | B15:17 | CVFQSNFQEF | |

| 11 | Pat132 | ERCC8 | A01:01 | FQSNFQEFY |

| Pat38 | ERCC8 | C02:02 | FQSNFQEFY | |

| 12 | Pat117 | FAM5B | A02:01 | FQDSALLQL |

| Pat117 | FAM5B | C07:01 | FQDSALLQL | |

| Pat117 | FAM5B | C02:02 | FQDSALLQL | |

| Pat123 | FAM5B | C04:01 | FQDSALLQL | |

| Pat123 | FAM5B | C02:02 | FQDSALLQL | |

| 13 | Pat117 | FAM5B | A02:01 | FQDSALLQLI |

| Pat117 | FAM5B | C02:02 | FQDSALLQLI | |

| Pat123 | FAM5B | C02:02 | FQDSALLQLI | |

| Pat123 | FAM5B | C04:01 | FQDSALLQLI | |

| 14 | Pat117 | FAM5B | C02:02 | YTQGFQDSAL |

| Pat123 | FAM5B | C02:02 | YTQGFQDSAL | |

| 15 | Pat21 | FAM83B | B08:01 | YARSCVPSL |

| Pat21 | FAM83B | C07:01 | YARSCVPSL | |

| Pat88 | FAM83B | C16:01 | YARSCVPSL | |

| Pat88 | FAM83B | B14:02 | YARSCVPSL | |

| 16 | Pat21 | FAM83B | C07:01 | YARSCVPSLF |

| Pat88 | FAM83B | C16:01 | YARSCVPSLF | |

| 17 | Pat105 | HSF5 | A02:01 | FVIGTEQAV |

| Pat174 | HSF5 | A02:01 | FVIGTEQAV | |

| 18 | Pat105 | HSF5 | C05:01 | GSDIMSFVI |

| Pat174 | HSF5 | C02:02 | GSDIMSFVI | |

| 19 | Pat138 | LATS2 | A32:01 | SLVETPNYI |

| Pat38 | LATS2 | A02:01 | SLVETPNYI | |

| 20 | Pat132 | LOX | A01:01 | HTQGLSPDCY |

| Pat38 | LOXL1 | B15:17 | HTQGLSPDCY | |

| 21 | Pat123 | MKLN1 | C02:02 | HSKNCCLYVF |

| Pat88 | MKLN1 | C16:01 | HSKNCCLYVF | |

| 22 | Pat21 | OR52N5 | A01:01 | LSPTLNPIVY |

| Pat49 | OR52N5 | A01:01 | LSPTLNPIVY | |

| 23 | Pat66 | TRBV5-1 | A01:01 | ISGHRSVFWY |

| Pat66 | TRBV5-1 | B58:01 | ISGHRSVFWY | |

| Pat174 | TRBV5-1 | A29:02 | ISGHRSVFWY | |

| 24 | Pat21 | UGT2B28 | C07:01 | FQYHSLNVI |

| Pat79 | UGT2B7 | A02:01 | FQYHSLNVI | |

| Pat79 | UGT2B7 | C02:02 | FQYHSLNVI | |

| 25 | Pat88 | ZIM3 | A03:01 | FIYKSDFVK |

| Pat38 | ZIM3 | A03:01 | FIYKSDFVK | |

| 26 | Pat38 | ZIM3 | B15:17 | KSDFVKHQRI |

| Pat88 | ZIM3 | C08:02 | KSDFVKHQRI | |

| 27 | Pat38 | ZIM3 | B15:17 | KAFIYKSDFV |

| Pat88 | ZIM3 | C16:01 | KAFIYKSDFV | |

| 28 | Pat88 | ZNF229 | A29:02 | RVHTGEKLY |

| Pat38 | ZNF235 | B15:17 | RVHTGEKLY |

To evaluate neoantigens most likely to engender an immune response, we next examined whether predicted immunogenic neoantigens were expressed in mutated tumors. Here, we leveraged paired DNA- and RNA-sequencing data obtained for 40 patients (13 with clinical benefit, 22 with no clinical benefit, and 5 showing long-term survival) from whom high-quality archival formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumor tissue was available (18). Among these patients, the median number of predicted neoantigens using nonsynonymous mutations and HLA typing alone was 395 per patient (range: 12 to 6984). Filtering these putative neoantigens by using patient-matched transcriptome data decreased the median neoantigen load to 198 per patient (range: 4 to 4622). A similar filtering approach that used unmatched melanoma gene expression data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) (18, 26) also eliminated neoantigens unlikely to be expressed (in this case, the median neoantigen load was 347 per patient; range: 12 to 6159); however, the remaining neoantigens only partially overlapped those that were inferred using patient-matched RNA (Fig. 2, C and D).

Conceivably, an inadequate immune response to tumor neoantigens could also be explained by aberrant HLA class I expression, which has been previously observed in melanoma (27). However, we found that HLA class I genes were expressed in all patients and in similar amounts across response groups (fig. S5, A and B). Moreover, somatic mutations in HLA class I genes were rare in this cohort and did not segregate by response group (table S5). Therefore, matched genome and transcriptome sequencing appeared to improve the identification of patient-specific neoantigens, which were not impacted by aberrant HLA expression or mutation status.

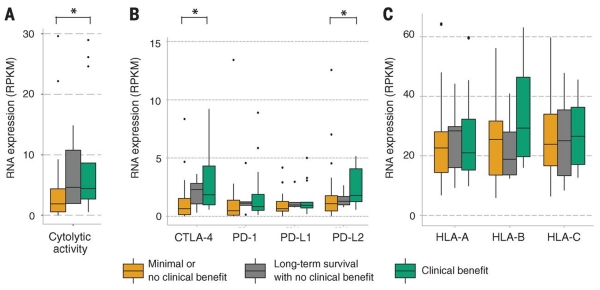

Finally, we leveraged the total transcriptome data from this cohort (42 patients total) to characterize an RNA expression profile in the tumor microenvironment previously associated with immune infiltrate. Specifically, the geometric mean of expression of granzyme A (GZMA) and perforin (PRF1) has been shown to correlate with both the cytolytic activity of local immune infiltrates and the neoantigen load (14, 15). Both genes were significantly enriched in the cohort treated with ipilimumab that had clinical benefit compared with the cohort that showed no clinical benefit (P = 0.042; Mann-Whitney) (Fig. 3A). Also, the cohort that had long-term survival expressed these cytolytic genes in amounts similar to those of the clinical-benefit group. Expression of CTLA-4 itself and of the programmed cell death 1 ligand 2 (PD-L2), which inhibits peripheral T cell proteins, was also significantly elevated in the cohort that showed clinical benefit compared with the one that showed no clinical benefit (P = 0.033 and P = 0.041; Mann-Whitney) (Fig. 3B). HLA class I proteins were expressed in similar amounts across clinical response groups (P > 0.05 for all; Mann-Whitney) (Fig. 3C). Together, these findings suggest that expression of immune checkpoint molecules themselves may correlate with immunotherapy response.

Fig. 3. Immune microenvironment cytolytic and immune activity correlates with response to ipilimumab.

(A) Patients who achieved clinical benefit from immune checkpoint blockade therapy had significantly higher levels of tumor cytolytic activity than those who had minimal or no benefit from ipilimumab (P = 0.039). (B) Patients who achieved clinical benefit from ipilimumab therapy had significantly higher levels of expression immune checkpoint receptors than those who did not (CTLA-4: P = 0.033, PD-L2: P = 0.041). One point is not shown because of an outlying high CTLA-4 expression value in a nonresponder patient (>50 reads per kilobase per million mapped reads). (C) Response to ipilimumab did not correlate with expression of or mutations in HLA alleles (P > 0.05 for all). Asterisks (*) indicate P < 0.05.

Overall, our findings imply that both DNA- and RNA-level genomic information may have predictive value for ipilimumab-based therapy. In contrast, recurrent neoantigens (e.g., those occurring in more than one ipilimumab responder) were rare in our cohort—and those that were observed were not necessarily matched by HLA type. These results suggest that the discovery of specific or recurrent neoantigens that mediate response to immunotherapy may require patient cohorts that are much larger in size than those currently available, especially given the importance of HLA restriction in mediating neoantigen recognition (10). Incorporation of patient-matched RNA-level information may help prioritize putative neoantigens and elucidate possible tumor immune microenvironmental effects, including interferon-related genes and additional immune checkpoint molecules that are relevant in melanoma (28). Additionally, prediction of neoantigens originating from fusion products and class II neoantigens may further inform genomic correlates of response (29–31).

In this study, we observed a distinct set of patients who experienced survival for a long time after treatment, despite the early progression of disease. Patterns of initial increases in tumor mass or delayed responses to therapy have been observed after cancer immunotherapy in the past (32). Thus, these observations raise the possibility that neoantigen loads or tumor cytolytic and immune checkpoint expression may play meaningful functional roles in this context, although these findings require further exploration in larger clinical cohorts. Additional studies of clinical response and resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitors may benefit from integrating exome and transcriptome sequencing data to inform the relative contributions of tumor immunogenicity and host immune infiltration in determining clinical benefit.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH U54 HG003067. All sequencing data are available in dbGap, accession number phs000452.v2.p1. We thank the Dermatologic Cooperative Oncology Group (DeCOG; Germany) for clinical accrual and sample coordination, S. Bahl (Broad) for project management effort, and the Broad Genomics Platform for piloting dual extraction and RNA sequencing from formalin samples. S.M.G. is supported by a fellowship from Janssen and is a paid adviser for Merck, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Roche, and Novartis. C.L. is a paid adviser for Merck, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Roche, and Novartis. L.A.G. is a consultant for Novartis, Foundation Medicine, and Boehringer Ingelheim, a paid adviser for Warp Drive, has ownership interest in Foundation Medicine, and holds a Commercial Research Grant from Novartis. E.M.V.A. is a paid adviser for Syapse and a consultant for Roche Ventana. E.M.V.A., D.M., B.S., D.S., and L.A.G. designed the study, performed the analyses, and wrote the manuscript. S.A.S., D.M., E.M.V.A. and C.J.W. performed HLA typing and neoantigen binder analyses. E.M.V.A., S.G., and L.A.G. performed sequencing. B.S., C.B., L.Z., A.S., M.H.G.F., S.M.G., J.U., J.C.H. B.W., K.C.K., C.L., P.M., R.G., R.D., and D.S. developed the clinical samples cohort. U.H. performed pathology review on the samples.

Footnotes

Supplementary Material

Please refer to Web version for supplementary materials.

Supplement. Materials and Methods, Figs. S1 to S4, Table S3

Table S1. Mutation list for all patients

Table S2. Detailed clinical and genome characteristics of individual patients

Table S4. Neoantigen list with HLA type and predicting MHC binding affinity for all patients

Table S5. Germline mutations in HLA class I

References

- 1.Robert C, et al. Ipilimumab plus dacarbazine for previously untreated metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2517–2526. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1104621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hodi FS, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:711–723. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Larkin J, et al. Combined nivolumab and ipilimumab or monotherapy in untreated melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:23–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Postow MA, et al. Nivolumab and ipilimumab versus ipilimumab in untreated melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2006–2017. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schadendorf D, et al. Pooled analysis of long-term survival data from phase II and phase III trials of ipilimumab in unresectable or metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:1889–1894. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.56.2736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maio M, et al. Five-year survival rates for treatment-naive patients with advanced melanoma who received ipilimumab plus dacarbazine in a phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:1191–1196. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.56.6018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carreno BM, et al. Cancer immunotherapy. A dendritic cell vaccine increases the breadth and diversity of melanoma neoantigen-specific T cells. Science. 2015;348:803–808. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa3828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gubin MM, et al. Checkpoint blockade cancer immunotherapy targets tumour-specific mutant antigens. Nature. 2014;515:577–581. doi: 10.1038/nature13988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yadav M, et al. Predicting immunogenic tumour mutations by combining mass spectrometry and exome sequencing. Nature. 2014;515:572–576. doi: 10.1038/nature14001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schumacher TN, Schreiber RD. Neoantigens in cancer immunotherapy. Science. 2015;348:69–74. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa4971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Rooij N, et al. Tumor exome analysis reveals neoantigen-specific T-cell reactivity in an ipilimumab-responsive melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:e439–442. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.47.7521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson DB, et al. Impact of NRAS mutations for patients with advanced melanoma treated with immune therapies. Cancer Immunol Res. 2015;3:288–295. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-14-0207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Snyder A, et al. Genetic basis for clinical response to CTLA-4 blockade in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2189–2199. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1406498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rooney MS, Shukla SA, Wu CJ, Getz G, Hacohen N. Molecular and genetic properties of tumors associated with local immune cytolytic activity. Cell. 2015;160:48–61. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown SD, et al. Neo-antigens predicted by tumor genome meta-analysis correlate with increased patient survival. Genome Res. 2014;24:743–750. doi: 10.1101/gr.165985.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spranger S, Bao R, Gajewski TF. Melanoma-intrinsic beta-catenin signalling prevents anti-tumour immunity. Nature. 2015;523:231–235. doi: 10.1038/nature14404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Allen EM, et al. Whole-exome sequencing and clinical interpretation of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tumor samples to guide precision cancer medicine. Nat Med. 2014;20:682–688. doi: 10.1038/nm.3559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Materials and methods are available as supplementary materials on Science Online.

- 19.Cibulskis K, et al. Sensitive detection of somatic point mutations in impure and heterogeneous cancer samples. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:213–219. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hodis E, et al. A landscape of driver mutations in melanoma. Cell. 2012;150:251–263. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eisenhauer EA, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schadendorf D, et al. Melanoma. Nat Rev Dis Prim. 2015;1:1–20. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2015.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rizvi NA, et al. Cancer immunology. Mutational landscape determines sensitivity to PD-1 blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Science. 2015;348:124–128. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Le DT, et al. PD-1 blockade in tumors with mismatch-repair Deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2509–2520. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1500596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schumacher TN, Kesmir C, van Buuren MM. Biomarkers in cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Cell. 2015;27:12–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2014.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.The Cancer Genome Atlas Network Genomic classification of cutaneous melanoma. Cell. 2015;161:1681–1696. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hofbauer GF, et al. High frequency of melanoma-associated antigen or HLA class I loss does not correlate with survival in primary melanoma. J Immunother. 2004;27:73–78. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200401000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sharma P, Allison JP. The future of immune checkpoint therapy. Science. 2015;348:56–61. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa8172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kreiter S, et al. Mutant MHC class II epitopes drive therapeutic immune responses to cancer. Nature. 2015;520:692–696. doi: 10.1038/nature14426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang RF, Wang X, Atwood AC, Topalian SL, Rosenberg SA. Cloning genes encoding MHC class II-restricted antigens: mutated CDC27 as a tumor antigen. Science. 1999;284:1351–1354. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5418.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Linnemann C, et al. High-throughput epitope discovery reveals frequent recognition of neo-antigens by CD4+ T cells in human melanoma. Nat Med. 2015;21:81–85. doi: 10.1038/nm.3773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wolchok JD, et al. Guidelines for the evaluation of immune therapy activity in solid tumors: immune-related response criteria. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:7412–7420. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cibulskis K, et al. ContEst: estimating cross-contamination of human samples in next-generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:2601–2602. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robinson JT, et al. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:24–26. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.