Abstract

Background

Glioma is one of the most common primary malignancies in the brain or spine. The transcription factor (TF) CCAAT/enhancer binding protein beta (CEBPB) is important for maintaining the tumor initiating capacity and invasion ability. To investigate the regulation mechanism of CEBPB in glioma, microarray data GSE47352 was analyzed.

Methods

GSE47352 was downloaded from Gene Expression Omnibus, including three samples of SNB19 human glioma cells transduced with non-target control small hairpin RNA (shRNA) lentiviral vectors for 72 h (normal glioma cells) and three samples of SNB19 human glioma cells transduced with CEBPB shRNA lentiviral vectors for 72 h (CEBPB-silenced glioma cells). The differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were screened using limma package and then annotated. Afterwards, the Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) software was applied to perform enrichment analysis for the DEGs. Furthermore, the protein-protein interaction (PPI) network and transcriptional regulatory network were constructed using Cytoscape software.

Results

Total 529 DEGs were identified in the normal glioma cells compared with the CEBPB-silenced glioma cells, including 336 up-regulated and 193 down-regulated genes. The significantly enriched pathways included chemokine signaling pathway (which involved CCL2), focal adhesion (which involved THBS1 and THBS2), TGF-beta signaling pathway (which involved THBS1, THBS2, SMAD5, and SMAD6) and chronic myeloid leukemia (which involved TGFBR2 and CCND1). In the PPI network, CCND1 (degree = 29) and CCL2 (degree = 12) were hub nodes. Additionally, CEBPB and TCF12 might function in glioma through targeting others (CEBPB → TCF12, CEBPB → TGFBR2, and TCF12 → TGFBR2).

Conclusions

CEBPB might act in glioma by regulating CCL2, CCND1, THBS1, THBS2, SMAD5, SMAD6, TGFBR2, and TCF12.

Keywords: Glioma, CCAAT/enhancer binding protein beta, Differentially expressed genes, Protein-protein interaction network, Transcriptional regulatory network

Background

Glioma, which is known as one of the most common primary malignancies in the brain or spine, accounts for nearly 30 % of all brain and central nervous system tumors and 80 % of all malignant brain tumors [1, 2]. Previous researches have shown that the most important hallmarks of malignant glioma are its invasion and angiogenesis [3]. So far, researchers have indicated that glioma can be induced by neurofibromatoses and tuberous sclerosis complex [4], electromagnetic radiation [5], DNA repair genes (such as excision repair cross-complementing 1, ERCC1, and X-ray repair cross-complementing group 1, XRCC1) [6]. However, the exact molecular mechanisms of glioma were still unclear.

In the central nervous system, the neoplastic transformation can convert the neural cells into cells of mesenchymal phenotype which possess the ability of invasion and promoting angiogenesis [7, 8]. What is more, it has been identified that mesenchymal stem cells (MSC)-like properties may play a role in the tumorigenesis, invasion, and recurrence of primary glioblastoma tumors [8]. The transcription factor (TF) CCAAT/enhancer binding protein beta (CEBPB) is associated with the mesenchymal state of primary glioblastoma, and its expression in glioma is important for maintaining the tumor initiating capacity and invasion ability [9, 10]. Moreover, the transforming growth factor beta 1/SMAD family member 3 (TGFB1/SMAD3) plays a key role in the extracellular matrix (ECM) production which can lead to glioblastoma aggression [11, 12]. It has been revealed that CEBPB can regulate the synthesis of ECM [13]. However, the regulation mechanism of CEBPB on TGFB1/SMAD3 in glioma was seldom studied.

In our study, in order to gain a better understanding of the regulation mechanisms of CEBPB and investigate whether CEBPB could regulate the production of ECM via the TGFB1/SMAD3 signaling pathway in glioma, the microarray data deposited by Carro et al. were further analyzed with bioinformatics methods. Firstly, the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between SNB19 human glioma cells transduced with non-target control small hairpin RNA (shRNA) lentiviral vectors for 72 h and SNB19 human glioma cells transduced with CEBPB shRNA lentiviral vectors for 72 h were identified and annotated. Subsequently, their potential functions were predicted by enrichment analysis. Finally, protein-protein interaction (PPI) network and transcriptional regulatory network were constructed to screen key genes.

Methods

Microarray dataset

The microarray dataset of GSE19114 [14] was downloaded from Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) database, which was based on the platform of GPL6947 IlluminaHumanHT-12 V3.0 expression beadchip. A total of 74 samples were included in the dataset, among which 3 samples of SNB19 human glioma cells transduced with non-target control shRNA lentiviral vectors for 72 h (normal glioma cells) and 3 samples of SNB19 human glioma cells transduced with CEBPB shRNA lentiviral vectors for 72 h (CEBPB-silenced glioma cells) were used to study the effect of CEBPB on glioma.

Data preprocessing and DEGs screening

The preprocessed microarray data were obtained from GEO2R of National Center of Biotechnology Information (NCBI, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/geo2r/), including 48803 probes. The linear models for microarray data (limma) package [15] were used to identify the DEGs between the normal glioma cells and the CEBPB-silenced glioma cells. Benjamini-Hochberg (BH) method [16] was applied to adjust the raw p value into false discovery rate (FDR). The FDR <0.05 and |log2 fold change (FC) >1 were used as cut-off criteria.

Functional and pathway enrichment analysis

Gene Ontology (GO, http://www.geneontology.org/) annotations are of great importance for mining biological and functional significance from large dataset [17]. The Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG, http://www.genome.ad.jp/kegg) database represents higher order of functions in terms of the network of the interacting molecules [18]. The Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) online tool [19] was employed to perform GO functional and KEGG pathway enrichment analyses for the DEGs. The p value <0.05 was used as the cut-off criterion.

DEGs annotation

TSGene database (http://bioinfo.mc.vanderbilt.edu/TSGene/), which contains detailed annotations for each tumor suppressor gene (TSG), such as cancer mutations, gene expressions, methylation sites, transcriptional regulations, and PPIs, was applied to identify the TSGs from the DEGs [20]. Additionally, tumor-associated gene (TAG) database (http://www.binfo.ncku.edu.tw/TAG/), which provides information about commonly shared functional domains in well-characterized oncogenes and TSGs, was used for screening the TAGs from the DEGs [21]. Besides, as a collection of data about the transcriptional regulatory network, the Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE) project was introduced for screening the TFs from the DEGs [22].

PPI network construction

The PPI pairs were searched using the Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes (STRING, http://string-db.org/) online tool [23]. The required confidence (combined score) >0.4 was used as the cut-off criterion. Then, the Cytoscape software [24] was used to visualize the PPI network. Furthermore, connectivity degree analysis was performed to search the hub nodes of PPI networks. The degree of a node was corresponded to the number of interactions involved it [25]. In addition, hub nodes were nodes with higher degrees.

Transcriptional regulatory network construction

ENCODE project is a collection of data about the transcriptional regulatory network, which helps illuminate TF-binding sites, histone marks, chromatin accessibility, DNA methylation, RNA expression, RNA binding, and other cell-state indicators [22]. Based on the transcriptional regulation interactions derived from ENCODE project, the regulatory network containing CEBPB and TGFB1/SMAD3 was constructed by Cytoscape software [24].

Results

Identification of DEGs

According to the analysis of the microarray dataset, a total of 529 DEGs (including 336 up-regulated genes and 193 down-regulated genes) were identified in the normal glioma cells compared with the CEBPB-silenced glioma cells. Among them, the top ten significantly up-regulated genes (such as thrombospondin 1 (THBS1) and chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 (CCL2)) and down-regulated genes (such as cyclin D1 (CCND1)) are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

The top ten up- and down-regulated genes

| DEGs | Gene symbol | FDR | Log2 FC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Up-regulated | AXL | 9.39E−07 | 1.846031 |

| SERPINE1 | 8.58E−07 | 1.741651 | |

| ITGB1 | 6.28E−08 | 1.739866 | |

| PRPF31 | 6.28E−08 | 1.644503 | |

| TXNDC5 | 3.26E−08 | 1.629988 | |

| WDFY1 | 3.26E−08 | 1.622947 | |

| AXL | 1.57E−07 | 1.554728 | |

| SLC1A3 | 5.96E−08 | 1.484443 | |

| SET | 3.90E−07 | 1.477058 | |

| ITGB1 | 2.66E−07 | 1.466634 | |

| Down−regulated | AKR1B10 | 3.26E−08 | −2.19537 |

| SLC2A3 | 6.28E−08 | −2.01825 | |

| HMOX1 | 6.28E−08 | −1.58464 | |

| CCND1 | 9.30E−08 | −1.49158 | |

| HIST1H2BK | 1.16E−07 | −1.38961 | |

| STX3 | 3.36E−07 | −1.2468 | |

| TDG | 8.98E−08 | −1.23629 | |

| SRXN1 | 8.97E−07 | −1.22479 | |

| DICER1 | 5.00E−07 | −1.20817 | |

| STK40 | 9.14E−07 | −1.19625 |

DEGs differentially expressed genes, FDR false discovery rate, FC fold change

Functional and pathway enrichment analysis

For the up-regulated genes, the enriched functions included transcription from RNA polymerase II promoter (p = 1.01E−03), cytoskeleton organization (p = 2.76E−04), and endocytosis (p = 2.57E−05) (Table 2A). Meanwhile, the down-regulated genes were mainly enriched in the function of enzyme-linked receptor protein signaling pathway (p = 2.89E−03), skin development (p = 4.97E−03), and response to hyperoxia (p = 2.97E−05) (Table 2B).

Table 2.

The top ten functions enriched for the differentially expressed genes

| GO ID | Description | Gene number | p value | Gene symbols |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A) | ||||

| GO:0006366 | Transcription from RNA polymerase II promoter | 47 | 1.01E−03 | SOX21, TCF25, TOP2A, GTF2F2, CIAO1, SERPINE1, DKK1, CYR61, SOX18, PAF1… |

| GO:0007010 | Cytoskeleton organization | 32 | 2.76E−04 | PTK2, DPYSL2, CNN3, BICD2, CLIC4, CTGF, EDN1, NRAS, ITGB1, RHOG… |

| GO:0006897 | Endocytosis | 23 | 2.57E−05 | PTK2, PIK3R2, THBS1, SERPINE1, DKK1, CYFIP2, AXL, RABEPK, LRP1B, ABCA1… |

| GO:0071375 | Cellular response to peptide hormone stimulus | 15 | 5.75E−04 | PTK2, PIK3R2, GNG10, PPM1A, GNG5, PIK3R1, ATP6V1G1, NRAS, SOCS2, GNG12… |

| GO:0000398 | mRNA splicing, via spliceosome | 10 | 1.02E−02 | PABPC1, GTF2F2, LSM7, LSM3, POLR2C, UPF3B, MBNL2, C1QBP, PRPF31, PAPOLA |

| GO:0048469 | Cell maturation | 9 | 8.96E−04 | SOX18, AXL, GJA1, DLD, FOXO3,TYMS,CLN5,EPAS1,PTBP3 |

| GO:0043200 | Response to amino acid stimulus | 7 | 6.71E−04 | CTGF, EDN1, CEBPB, TYMS, CCL2, LAMTOR3, LAMTOR1 |

| GO:0006112 | Energy reserve metabolic process | 7 | 4.38E−02 | GNG10, GNG5, GFPT2, RAP1B, PPP1CC, GNG12, PYGB |

| GO:0018279 | Protein N-linked glycosylation via asparagine | 6 | 1.02E−02 | UGGT1, MLEC, GFPT2, B4GALT5, PGM3, STT3B |

| GO:0006261 | DNA-dependent DNA replication | 6 | 1.49E−02 | POLB, MCM3, RFC5, TOP2A, BAZ1A, RPAIN |

| (B) | ||||

| GO:0007167 | Enzyme-linked receptor protein signaling pathway | 19 | 2.89E−03 | KANK1, RTN4, ATP6V1D, PTPRK, EEF2K, ERRFI1, CGN, TGFBR2, ATP6V0A1, MVP… |

| GO:0043588 | Skin development | 9 | 4.97E−03 | PTHLH, ALDH3A2, ERRFI1, YAP1, STK4, EMP1, COL5A2, NCOA3, DICER1 |

| GO:0030330 | DNA damage response, signal transduction by p53 class mediator | 7 | 1.41E−04 | NDRG1, SPRED1, PSME3, CDKN1A, E2F7, CASP2, HIPK2 |

| GO:0001890 | Placenta development | 7 | 4.74E−04 | TXNRD1, ADM, CCNF, SPP1, STK4, NDP, E2F7 |

| GO:0031100 | Organ regeneration | 5 | 6.05E−05 | ADM, TGFBR2, CCND1, LCP1, CDKN1A |

| GO:0071456 | Cellular response to hypoxia | 5 | 2.26E−03 | HMOX1, NPEPPS, NDRG1, BNIP3, HIPK2 |

| GO:0048002 | Antigen processing and presentation of peptide antigen | 5 | 4.35E−02 | CTSD, NPEPPS, PSME3, AP1S1, AP1S2 |

| GO:0055093 | Response to hyperoxia | 4 | 2.97E−05 | TXNRD1, BNIP3, CAV1, CDKN1A |

| GO:0000188 | Inactivation of MAPK activity | 4 | 1.36E−04 | DUSP5, SPRED1, CAV1, DUSP22 |

| GO:0060443 | Mammary gland morphogenesis | 4 | 2.15E−03 | PTHLH, TGFBR2, CAV1, NCOA3 |

GO Gene Ontology, ID identification

(A) The top ten functions enriched for the up-regulated genes. (B) The top ten functions enriched for the down-regulated genes

Among the up-regulated genes, CCL2 was significantly enriched in the pathway of chemokine signaling pathway (p = 1.63E−03). THBS1 and thrombospondin 2 (THBS2) were significantly involved in the pathway of focal adhesion (p = 7.54E−03). And the up-regulated genes, such as THBS1, THBS2, SMAD family member 5 (SMAD5) and SMAD family member 6 (SMAD6), were significantly enriched in transforming growth factor beta (TGF-beta) signaling pathway (p = 4.83E−02) (Table 3A). Meanwhile, the down-regulated transforming growth factor beta receptor II (TGFBR2) and CCND1 were significantly enriched in both the pathways of chronic myeloid leukemia (p = 9.85E−03) and pancreatic cancer (p = 4.69E−02) (Table 3B).

Table 3.

The pathways enriched for the differentially expressed genes

| KEGG ID | Name | Gene number | p value | Gene symbols |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A) | ||||

| 4062 | Chemokine signaling pathway | 12 | 1.63E−03 | PTK2, PIK3R2, GNG10, GNG5, RAP1B, PIK3R1, NRAS, IL8, GNG12, CSK, FOXO3, CCL2 |

| 4510 | Focal adhesion | 11 | 7.54E−03 | PTK2, PIK3R2, THBS1, THBS2, RAP1B, PPP1CC, PIK3R1, ITGB1, ACTG1, FLNB, CAV2 |

| 4810 | Regulation of actin cytoskeleton | 11 | 1.18E−02 | PTK2, PIK3R2, CYFIP2, PPP1CC, PIK3R1, NRAS, ITGB1, GNG12, ACTG1, CSK, ARHGEF6 |

| 4910 | Insulin signaling pathway | 9 | 5.22E−03 | PIK3R2, PPP1CC, PIK3R1, NRAS, SOCS2, PTPN1, PYGB, CALM2, PTPRF |

| 3013 | RNA transport | 9 | 9.27E−03 | PABPC1, EIF3A, NUP54, EIF3G, UPF3B, NUP155, KPNB1, NUP37, EIF2S3 |

| 4145 | Phagosome | 8 | 2.82E−02 | TAP1, THBS1, THBS2, ATP6V1G1, ITGB1, ACTG1, LAMP2, DYNC1LI2 |

| 5100 | Bacterial invasion of epithelial cells | 7 | 1.24E−03 | PTK2, PIK3R2, PIK3R1, ITGB1, RHOG, ACTG1, CAV2 |

| 5142 | Chagas disease (American trypanosomiasis) | 7 | 1.13E−02 | PIK3R2, SERPINE1, GNA11, PIK3R1, IL8, IFNGR1, CCL2 |

| 4722 | Neurotrophin signaling pathway | 7 | 3.05E−02 | PIK3R2, RAP1B, PIK3R1, NRAS, CALM2, CSK, FOXO3 |

| 4360 | Axon guidance | 7 | 3.28E−02 | PTK2, DPYSL2, SEMA4F, NRAS, ITGB1, SLIT2, EFNA1 |

| 5131 | Shigellosis | 6 | 3.01E−03 | ITGB1, IL8, RHOG, ACTG1, FBXW11, CSK |

| 5211 | Renal cell carcinoma | 5 | 2.45E−02 | PIK3R2, RAP1B, PIK3R1, NRAS, EPAS1 |

| 5412 | Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC) | 5 | 3.03E−02 | ITGB1, DAG1, GJA1, ACTG1, CDH2 |

| 5410 | Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | 5 | 4.62E−02 | TPM3, ITGB1, DAG1, TPM1, ACTG1 |

| 4350 | TGF-beta signaling pathway | 5 | 4.83E−02 | THBS1, THBS2, SMAD6, ID3, SMAD5 |

| 20 | Citrate cycle (TCA cycle) | 4 | 5.11E−03 | CS, DLD, DLAT, SDHA |

| 5144 | Malaria | 4 | 3.19E−02 | THBS1, THBS2, IL8, CCL2 |

| 5213 | Endometrial cancer | 4 | 3.39E−02 | PIK3R2, PIK3R1, NRAS, FOXO3 |

| 5223 | Non-small cell lung cancer | 4 | 3.82E−02 | PIK3R2, PIK3R1, NRAS, FOXO3 |

| 3410 | Base excision repair | 3 | 4.23E−02 | POLB, PARP1, PARP3 |

| (B) | ||||

| 4144 | Endocytosis | 9 | 4.62E−04 | ASAP2, VPS36, TGFBR2, ASAP1, CAV1, SH3KBP1, EHD1, RAB22A, DNM3 |

| 4142 | Lysosome | 7 | 4.55E−04 | CTSD, TPP1, ATP6V0A1, ABCB9, AP1S1, AP1S2, NEU1 |

| 2010 | ABC transporters | 4 | 1.58E−03 | ABCC2, ABCC3, ABCB9, ABCC5 |

| 10 | Glycolysis/gluconeogenesis | 4 | 6.56E−03 | ENO2, ALDH3A2, PGAM1, PGK1 |

| 5220 | Chronic myeloid leukemia | 4 | 9.85E−03 | TGFBR2, CCND1, CDKN1A, BCL2L1 |

| 561 | Glycerolipid metabolism | 3 | 1.98E−02 | ALDH3A2, AGPAT9, LCLAT1 |

| 5212 | Pancreatic cancer | 3 | 4.69E−02 | TGFBR2, CCND1, BCL2L1 |

| 4966 | Collecting duct acid secretion | 2 | 3.85E−02 | ATP6V1D, ATP6V0A1 |

| 650 | Butanoate metabolism | 2 | 4.67E−02 | AKR1B10, HMGCS1 |

(A) The pathways enriched for the up-regulated genes. (B) The pathways enriched for the down-regulated genes. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes, KEGG; identification, ID

The annotation of DEGs

A total of 54 DEGs were screened as TAGs, including 33 up-regulated and 21 down-regulated genes. Among the 33 up-regulated genes, there were 22 TSGs (such as THBS1), 6 oncogenes, and 5 other genes (such as CCL2). Meanwhile, there were 13 TSGs, 4 oncogenes (such as CCND1), and 4 other genes in the 21 down-regulated genes. Additionally, 9 DEGs were screened as the TFs, including 8 up-regulated and 1 down-regulated genes (Table 4).

Table 4.

The identified transcription factors (TFs) and tumor associated genes (TAGs) among the differentially expressed genes (DEGs). Tumor suppressed genes, TSGs

| DEGs | TF numbers | TFs | TAG numbers | TAGs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TSGs | Oncogenes | Others | ||||

| Up-regulated | 1 | KLF12 | 33 | BAP1, THBS1, DKK1, PAF1, ST13, LRP1B, PDGFRL, ITGB1, TPM1, GJA1, CDH11, SLIT2, GLIPR1, FAT1, SOD2, FOXO3, EFNA1, GAS1, PTPRF, RAD51C, CAV2, SDHA | SET, CCNA2, AXL, NRAS, ROS1, SCK | GTF2F2, CTGF, FHL2, C1QBP, CCL2 |

| Down-regulated | 8 | ASCL1, ETV4, HSF1, LMO3, PML, RUNX3, TCF7, USF2 | 21 | HIPK2, YAP1, ERRFI1, PTPRK, KANK1, BNIP3L, DUSP22, SASH1, CDKN1A, NDRG4, ZFHX3, NDRG1, TGFBR2, | BCL2L2, NCOA3, CCND1, CDC25B | PTHLH, EMP1, CAV1, GLS |

PPI network analysis

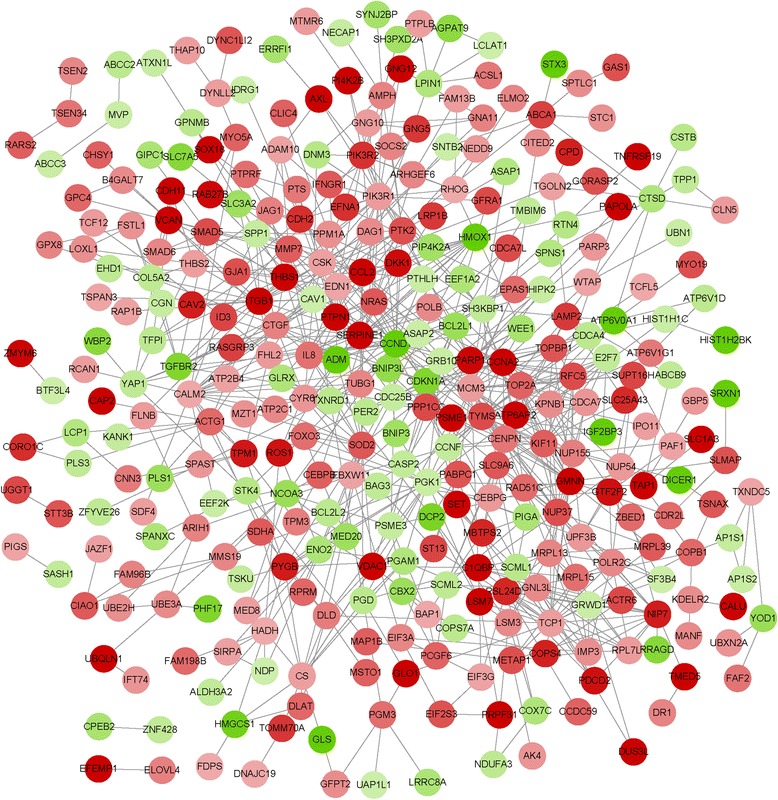

The constructed PPI network was consisted of 810 interactions (such as CCND1-THBS1 and THBS1-CCL2) (Fig. 1). Besides, the top 10 % nodes with higher degrees in the PPI network were identified, including CCND1 (degree = 29) and CCL2 (degree = 12) (Table 5).

Fig. 1.

The protein-protein interaction (PPI) network for the differentially expressed genes (DEGs). The red circles represent the up-regulated genes. The green circles indicate the down-regulated genes

Table 5.

The top 10 % DEGs with higher degrees in the protein-protein interaction (PPI) network

| Gene | Degree | Gene | Degree | Gene | Degree | Gene | Degree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCND1 | 29 | SOD2 | 19 | CENPN | 16 | KIF11 | 15 |

| PIK3R1 | 25 | TYMS | 19 | CAV1 | 16 | PTK2 | 15 |

| PGK1 | 22 | CDKN1A | 18 | PIK3R2 | 16 | EDN1 | 14 |

| NUP37 | 22 | PARP1 | 18 | CTGF | 15 | CS | 13 |

| CALM2 | 21 | TOP2A | 18 | RFC5 | 15 | CCL2 | 13 |

| MCM3 | 21 | ITGB1 | 18 | NUP155 | 15 | RSL24D1 | 12 |

| GMNN | 20 | TCP1 | 18 | NRAS | 15 | CDCA7 | 12 |

| CCNA2 | 20 | SERPINE1 | 17 | NIP7 | 15 | BCL2L1 | 12 |

Transcriptional regulatory network analysis

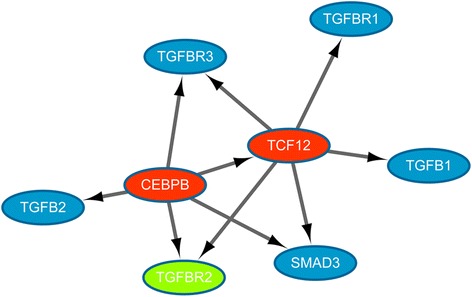

For further study, the regulation of TGFB1/SMAD3 by CEBPB, the transcriptional regulation interactions related to TGFB1/SMAD3, and the members of TGFB family were screened out from the ENCODE database and the transcriptional regulatory network was visualized by Cytoscape software (Fig. 2). The transcriptional regulation network showed that the CEBPB could regulate SMAD3, transcription factor 12 (TCF12), transforming growth factor beta 2 (TGFB2), TGFBR2, and TGFBR3 directly. Additionally, TCF12 targeted TGFB1, TGFBR1, TGFBR2, TGFBR3, and SMAD3.

Fig. 2.

The transcriptional regulatory network involving CEBPB and TGFB1/SMAD3. The red and green nodes represent the up-regulated and down-regulated genes, respectively. The blue nodes stand for non-differentially expressed genes (DEGs). The arrows represent regulatory relationships

Discussion

In this study, a total of 529 DEGs were obtained, including 336 up-regulated genes and 193 down-regulated genes. Enrichment analysis indicated that the up-regulated CCL2 was significantly enriched in the chemokine signaling pathway. Reports have found that chemokine expressed by stromal cells or endogenously produced in glioma cells may play key roles in tumor cell migration, invasion, proliferation, angiogenesis and immune cell infiltration in the tumor mass [26]. The chemokine CCL2 can promote glioma tumor aggressiveness by promoting attraction of T regulatory cells (which suppress the lymphocyte anti-tumor effector function) and microglial cells (which can reduce the anti-tumor functions and secrete pro-invasive metalloproteinases) [27, 28]. Meanwhile, metalloproteinases can promote the glioma invasion through the detachment of ECM [29]. Besides, results of DEGs annotation showed that CCL2 was screened out as a TAG. Therefore, we speculated that the increased expression of CCL2 could promote glioma aggressiveness through the pathway of chemokine signaling.

In addition, some up-regulated genes (such as THBS1, THBS2, SMAD5, and SMAD6) were significantly enriched in the TGF-beta signaling pathway in our study. Recently, it has been reported that the TGFB is a key factor in controlling migration, invasion and angiogenesis in glioblastoma and induces profound immunosuppression [30]. Besides, the THBS1 (belonging to thrombospondin family), which is referred as a TGFB activating protein, induces the glioma invasion [31]. THBS1 is a powerful anti-angiogenesis protein in glioblastoma [32]. These suggested that THBS1 might play a key role in regulating the angiogenesis in glioma. As another member of thrombospondin family, THBS2 may be a potential inhibitor of tumor growth and angiogenesis [33]. Moreover, it has been shown that THBS2 can function as an endogenous inhibitor of angiogenesis through directly affecting endothelial cell migration, proliferation, survival, and apoptosis [34]. In our study, we also found that THBS1 and THBS2 were significantly involved in the pathway of focal adhesion. Previous study reported that focal adhesion can suppress the migration and metastasis of tumor cells [35]. Therefore, we speculated that THBS1 and THBS2 could regulate angiogenesis and invasion in glioma via TGF-beta signaling pathway and focal adhesion pathway. Former researches have shown that SMAD6 is an inhibitor of TGFB signaling and blocked the phosphorylation of receptor-regulated SMADs (such as SMAD5) in the cytoplasm [36]. As a result, we assumed that SMAD5 and SMAD6 might affect glioma by regulating the TGFB signaling. In the PPI network, THBS1 could interact with CCL2, to some extent, indicating that THBS1 might play key roles in glioma through regulating CCL2. Consequently, THBS1, THBS2, SAMD5 and SMAD6 could be key factors involved in the CEBPB-silenced glioma.

Moreover, CCND1, as a member of the cyclin family, possessed the highest degree in the PPI network. Cyclins can modulate tumor cell cycle through alterations in cyclin-dependent kinase activity [37]. What’s more, researchers have discovered that overexpression of CCND1 can elevate the proliferation and invasion potential of human glioblastoma cells [38]. In the PPI network, we also found that CCND1 had interaction with THBS1, suggesting that CCND1 could be involved in regulating proliferation and invasion of glioma via interacting with THBS1.

TGFBR2 plays a key role in TGFB signal propagation via activating TGFBR1 and the phosphorylation of SMAD proteins [39]. Moreover, silencing of TGFBR2 can abolish TGFB-induced invasion and migratory responses of glioblastoma in vitro [40]. In our study, we also discovered that the up-regulated TCF12 could regulate TGFB1 and SMAD3, indicating that CEBPB might regulate TGFB1 and SMAD3 through TCF12. Previous studies have shown that TGFB1/SMAD3 can promote tumor cell migration, invasion and metastasis through inducing epithelial-mesenchymal transition [41, 42]. What is more, TCF12 has been found to suppress the expression of E-cadherin, which can lead to the metastasis of tumor cells [43]. Therefore, we assumed that CEBPB might regulate TGFBR2 and SMAD3 through TGF-β1/SMAD3 signaling pathway in glioma, and CEBPB could also affect metastasis of glioma by regulating TCF12. However, in our study, TGFB1 and SMAD3 were not significantly expressed, which might due to the relatively short time for CEBPB silencing. In our further research, the regulation of CEBPB on TGFB1/SMAD3 will be studied with CEBPB-silenced for a relatively long time.

Conclusions

We conducted a comprehensive bioinformatics analysis to identify genes which may be correlated with CEBPB-silenced glioma. A total of 529 DEGs were identified in the normal glioma cells compared with the CEBPB-silenced glioma cells. Besides, The identified DEGs, such as TCF12, TGFBR2, CCL2, THBS1, THBS2, SMAD5, SMAD6, and CCND1, might play important roles in the progression of glioma via the regulation of CEBPB. However, further researches are still needed to unravel their action mechanisms in glioma.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

None.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are too many to share. There was no new software.

Authors’ contributions

CHD and PP participated in the design of this study, and they both performed the statistical analysis. PP, YJ, QZ, JSB, and CL carried out the study and collected important background information. CHD and PP drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- BH

Benjamini-Hochberg

- DEGs

Differentially expressed genes

- ECM

Extracellular matrix

- ENCODE

Encyclopedia of DNA Elements

- FDR

False discovery rate

- GEO

Gene Expression Omnibus

- KEGG

The Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- MSC

Mesenchymal stem cells

- PPI

Protein-protein interaction

- TAG

Tumor-associated gene

- TF

Transcription factor

- TSG

Tumor suppressor gene

Contributor Information

Chenghua Du, Phone: +86-0475-8506178, Email: ChenghuaDuchd@163.com.

Pan Pan, Email: panpandoublep@163.com.

Yan Jiang, Email: yanjiangyjy@163.com.

Qiuli Zhang, Email: qiulizhangqlz@163.com.

Jinsuo Bao, Email: jinsuobaojsb@163.com.

Chang Liu, Email: changliuclc@163.com.

References

- 1.Mei P, Bai J, Shi M, Liu Q, Li Z, Fan Y, Zheng J. BRMS1 suppresses glioma progression by regulating invasion. Migration and adhesion of glioma cells. PLoS One. 2014;9:e98544. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 2.Goodenberger ML, Jenkins RB. Genetics of adult glioma. Cancer Genet. 2012;205:613–621. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergen.2012.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Onishi M, Ichikawa T, Kurozumi K, Date I. Angiogenesis and invasion in glioma. Brain Tumor Pathol. 2011;28:13–24. doi: 10.1007/s10014-010-0007-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reuss D, von Deimling A. Hereditary tumor syndromes and gliomas. In: Gliomas. Heidelberg: Springer Berlin; 2009. p. 83-102. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Cancer IAfRo . IARC classifies radiofrequency electromagnetic fields as possibly carcinogenic to humans. Lyon: World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fahmideh MA, Schwartzbaum J, Frumento P, Feychting M. Association between DNA repair gene polymorphisms and risk of glioma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuro Oncol. 2014;16:807–814. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nou003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Phillips HS, Kharbanda S, Chen R, Forrest WF, Soriano RH, Wu TD, Misra A, Nigro JM, Colman H, Soroceanu L. Molecular subclasses of high-grade glioma predict prognosis, delineate a pattern of disease progression, and resemble stages in neurogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:157–173. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tso C-L, Shintaku P, Chen J, Liu Q, Liu J, Chen Z, Yoshimoto K, Mischel PS, Cloughesy TF, Liau LM. Primary glioblastomas express mesenchymal stem-like properties. Mol Cancer Res. 2006;4:607–619. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-06-0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh R, Sharma MC, Sarkar C, Singh M, Chauhan SS. Transcription factor C/EBP-β mediates downregulation of dipeptidyl-peptidase III expression by interleukin-6 in human glioblastoma cells. FEBS J. 2014;281:1629–1641. doi: 10.1111/febs.12728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aguilarmorante D, Moralesgarcia JA, Santos A, Perezcastillo A. CCAAT/enhancer binding protein β induces motility and invasion of glioblastoma cells through transcriptional regulation of the calcium binding protein S100A4. Oncotarget. 2015;6:454–463. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Okano K, Hibi A, Miyaoka T, Inoue T, Sugimoto H, Tsuchiya K, Akiba T, Nitta K. Inhibitory effects of the transcription factor Ets-1 on the expression of type I collagen in TGF-β1-stimulated renal epithelial cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2012;369:247–254. doi: 10.1007/s11010-012-1388-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barnes JM, Weaver VM. Abstract B04: the role of mechanical force and integrin-ECM signaling in glioblastoma aggression. Cancer Res. 2013;73:B04. doi: 10.1158/1538-7445.FBCR13-B04. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luft FC. C/EBPβ LIP induces a tumor menagerie making it an oncogene. J Mol Med. 2015;93:1–3. doi: 10.1007/s00109-014-1224-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carro MS, Lim WK, Alvarez MJ, Bollo RJ, Zhao X, Snyder EY, Sulman EP, Anne SL, Doetsch F, Colman H. The transcriptional network for mesenchymal transformation of brain tumours. Nature. 2009;463:318–325. doi: 10.1038/nature08712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, Hu Y, Law CW, Shi W, Smyth GK. Limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghosh D. Incorporating the empirical null hypothesis into the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol. 2012;11:1–21. doi: 10.1515/1544-6115.1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Consortium GO. Gene ontology consortium: going forward. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:1049–1056. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Du J, Yuan Z, Ma Z, Song J, Xie X, Chen Y. KEGG-PATH: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes-based pathway analysis using a path analysis model. Mol Biosyst. 2014;10:2441–2447. doi: 10.1039/C4MB00287C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiao X, Sherman BT, Huang DW, Stephens R, Baseler MW, Lane HC, Lempicki RA. DAVID-WS: a stateful web service to facilitate gene/protein list analysis. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:1805–1806. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao M, Sun J, Zhao Z. TSGene: a web resource for tumor suppressor genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D970–D976. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen J-S, Hung W-S, Chan H-H, Tsai S-J, Sun HS. In silico identification of oncogenic potential of fyn-related kinase in hepatocellular carcinoma. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:420–427. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raney BJ, Cline MS, Rosenbloom KR, Dreszer TR, Learned K, Barber GP, Meyer LR, Sloan CA, Malladi VS, Roskin KM, et al. ENCODE whole-genome data in the UCSC genome browser (2011 update) Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:30. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Franceschini A, Szklarczyk D, Frankild S, Kuhn M, Simonovic M, Roth A, Lin J, Minguez P, Bork P, von Mering C. STRING v9. 1: protein-protein interaction networks, with increased coverage and integration. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D808–D815. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saito R, Smoot ME, Ono K, Ruscheinski J, Wang P-L, Lotia S, Pico AR, Bader GD, Ideker T. A travel guide to Cytoscape plugins. Nat Methods. 2012;9:1069–1076. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chao W, Zhu J, Zhang X. Integrating gene expression and protein-protein interaction network to prioritize cancer-associated genes. BMC Bioinf. 2012;13:1–10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-13-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Domanska UM, Kruizinga RC, Dunnen WFAD, Timmer-Bosscha H, Vries EGED, Walenkamp AME. The chemokine network, a newly discovered target in high grade gliomas. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2011;79:154–163. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2010.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carrillo-de Sauvage MA, Gómez A, Ros CM, Ros-Bernal F, Martín ED, Perez-Vallés A, Gallego-Sanchez JM, Fernández-Villalba E, Sr BC, Jr BC. CCL2-expressing astrocytes mediate the extravasation of T lymphocytes in the brain. Evidence from patients with glioma and experimental models in vivo. PLoS One. 2012;7:e30762. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lindemann C, Marschall V, Weigert A, Klingebiel T, Fulda S. Smac mimetic-induced upregulation of CCL2/MCP-1 triggers migration and invasion of glioblastoma cells and influences the tumor microenvironment in a paracrine manner 1. Neoplasia. 2015;17:481–489. doi: 10.1016/j.neo.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Könnecke H, Bechmann I. The role of microglia and matrix metalloproteinases involvement in neuroinflammation and gliomas. Clin Dev Immunol. 2013;2013:914104. doi: 10.1155/2013/914104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roth P, Silginer M, Goodman SL, Hasenbach K, Thies S, Maurer G, Schraml P, Tabatabai G, Moch H, Tritschler I. Integrin control of the transforming growth factor-β pathway in glioblastoma. Brain. 2013;136:564–576. doi: 10.1093/brain/aws351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seliger C, Leukel P, Moeckel S, Jachnik B, Lottaz C, Kreutz M, Brawanski A, Proescholdt M, Bogdahn U, Bosserhoff A-K. Lactate-modulated induction of THBS-1 activates transforming growth factor (TGF)-beta2 and migration of glioma cells in vitro. PLoS One. 2013;8:e78935. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brooks MD, Jackson E, Piwnica-Worms D, Mitre RD, Rubin JB. Cancer research. Philadelphia: AMER Assoc Cancer Research; 2013. Downregulation of THBS1 is a critical step in glioblastoma angiogenesis. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hawighorst T, Velasco P, Streit M, Hong YK, Kyriakides TR, Brown LF, Bornstein P, Detmar M. Thrombospondin‐2 plays a protective role in multistep carcinogenesis: a novel host anti‐tumor defense mechanism. EMBO J. 2001;20:2631–2640. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.11.2631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lawler PR, Lawler J. Molecular basis for the regulation of angiogenesis by thrombospondin-1 and -2. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2:a006627. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jarjour AA, Durko M, Luk TL, Marçal N, Shekarabi M, Kennedy TE. Autocrine netrin function inhibits glioma cell motility and promotes focal adhesion formation. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25408. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jung SM, Lee JH, Park J, Oh YS, Lee SK, Park JS, Lee YS, Kim JH, Lee JY, Bae YS, et al. Smad6 inhibits non-canonical TGF-β1 signalling by recruiting the deubiquitinase A20 to TRAF6. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2562. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Casimiro MC, Crosariol M, Loro E, Li Z, Pestell RG. Cyclins and cell cycle control in cancer and disease. Genes Cancer. 2012;3:649–657. doi: 10.1177/1947601913479022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Phull P, Shipley A, Mowat N. NOTCH3 is a prognostic factor that promotes glioma cell proliferation, migration and invasion via activation of CCND1 and EGFR. PLoS One. 2013;8:271–272. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rožmarić M, Ivšić AG, Grahek Ž. TGF-beta induced Erk phosphorylation of smad linker region regulates smad signaling. PLoS One. 2012;7:2016. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wesolowska A, Kwiatkowska A, Slomnicki L, Dembinski M, Master A, Sliwa M, Franciszkiewicz K, Chouaib S, Kaminska B. Microglia-derived TGF-β as an important regulator of glioblastoma invasion—an inhibition of TGF-β-dependent effects by shRNA against human TGF-β type II receptor. Oncogene. 2007;27:918–930. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fuxe J, Vincent T, Garcia de Herreros A. Transcriptional crosstalk between TGF-beta and stem cell pathways in tumor cell invasion: role of EMT promoting Smad complexes. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:2363–2374. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.12.12050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bae E, Kim S-J, Hong S, Liu F, Ooshima A. Smad3 linker phosphorylation attenuates Smad3 transcriptional activity and TGF-β1/Smad3-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in renal epithelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;427:593–599. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.09.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee CC, Chen WS, Chen CC, Chen LL, Lin YS, Fan CS, Huang TS. TCF12 protein functions as transcriptional repressor of E-cadherin, and its overexpression is correlated with metastasis of colorectal cancer. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;287:2798–2809. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.258947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are too many to share. There was no new software.