Abstract

Introduction

Payments to practitioners from drug and device manufacturers or group purchasing organizations are reported in the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) databases as a part of the Sunshine Act. Characterizing these payments is a necessary step to identifying conflicts of interest and the influence of payments on practice patterns, if any. Payments have never been analyzed in detail amongst Urologists.

Materials and Methods

We reviewed the most recent CMS Open Payments database for the full year 2014, released on June 30, 2015. Urology practitioners were extracted and the database was analyzed for number of total payments, total dollar value of payments, mean, median, number of physicians, number of manufacturers, and number of drugs/biologicals. Data were further categorized according to provider specialty, form of payment, nature of payment, practitioner ownership, and dispute status.

Results

Payments totaled $32,450,382. Practitioner payments were unevenly distributed, with a median payment of $15. The majority of payments were in the form of food and beverage. Female pelvic medicine practitioners received the highest payments out of the provider specialties. The largest categorical difference from the median was in the form of stock, options, and other ownership interests ($24,050). Ownership status and disputed payments were associated with payment values above median values ($400 and $61, respectively).

Conclusions

There are major disparities in industry payments to urology practitioners. Whether or not this influences practice patterns remains to be seen, though identifying categorical differences in payments is an important first step in the process.

Keywords: physician payments, urologist payments, sunshine act, compensation

INTRODUCTION

Financial ties between health care providers and manufacturers of pharmaceutical and medical devices have long been scrutinized and are a matter of public interest1. On March 23, 2010, congress signed into law Section 6002 as part of HR3590, better known as the “Sunshine Act” of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. Its intent was to speak to public concerns over physician and industry relationships, clarify financial relationships, consolidate a location for reporting and monitoring, and stop dishonest research, education and clinical decision-making2. Though it is common practice to disclose conflicts of interest in educational lectures, the Sunshine Act dramatically expands the criteria and accessibility to this information. On February 8, 2013, the final rulings were decided and the first full year of disclosures for 2014 was published on June 30, 20153, 4.

To our knowledge, payments from manufacturers and group-purchasing organizations to physicians have never been described amongst Urologists. Whether or not there is an influence of payments on practice patterns is an ongoing topic of investigation5–7. Quantifying the magnitude and nature of such payments is an important first step to establishing the absence or presence of conflicts of interest.

Our study sought to identify the characteristics of payments within the Sunshine Act database. Special attention was drawn to categories where payments were disproportionately distributed. Analysis at this level will enable investigators to better focus study of influence on practice patterns in the future.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data and Study Population

We used the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Open Payments files to identify all payments to healthcare providers from covered manufacturers and group-purchasing organizations. A covered manufacturer produces products that are eligible for payment by Medicare, Medicaid, or Children’s Health Insurance Program and are under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Three databases were available: Research, Ownership, and General Payments. The Research database involves research-related payments, Ownership measures magnitude of ownership stakes, and General Payments consist of all other payment types. Urologists were identified from the 2014 General Payments database by filtering by Physician Specialty. Listed urologist specialties were Urology (herein categorized as General Urology), Female Pelvic Medicine, and Pediatric Urology. Ownership stakes are contained within the Ownership database, though payments in a given year with equity/investment interests are included within the General Payments database as a form of compensation. Teaching hospitals were excluded because data on individual beneficiaries are not listed in this categorization; however, individual providers who are employed by teaching hospitals are included in the analysis. We excluded 2,579 recipients who were Nurses and 15 recipients who were Doctors of Dentistry and Doctors of Optometry. 6 payments were valued at $0.00 (all to one physician), and were excluded. Our final cohort included 235,239 payments, among 9,343 recipients.

Payment Characteristics

Recipient data were recorded including recipient ID, first name, middle name, last name, suffix, address, state, and ZIP code. Provider data were recorded including physician type, physician specialty, and license state. Manufacturer information included ID, name, state, name of drug or biological, and ID of drug or biological. Payment information included payment amount, date, number of payments, form of payment, nature of payment, physician ownership indicator, dispute status indicator, and third-party recipient identifiers if applicable. Payment characteristics were stratified for analysis across provider specialty, form of payment, nature of payment, ownership indicator, and dispute status.

Statistical Analysis

We first summarized payment characteristics in the CMS database. Parametric variables are presented as means and standard deviations (SD). Non-parametric variables are presented as medians and interquartile ranges (IQR). We then examined the characteristics of payments and the top 10 payments to Urology practitioners. Next, the distribution of payments was analyzed according to cumulative percent. Lastly, we generated box plots of payments stratified according to provider specialty, form of payment, and ownership indicator. Due to the significant skew of the data, a log10 transformation was performed on payments prior to graphing boxplots to enable visual clarity. We did not perform descriptive statistics because categories of payments are not independent variables and there are a large number of observations. Therefore data are presented without p-values. Sensitivity analysis was performed on total payments, means and medians by performing two-tailed exclusions at the 1% and 5% levels. All analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics software, version 22 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). This study utilized a public database and was IRB exempt.

RESULTS

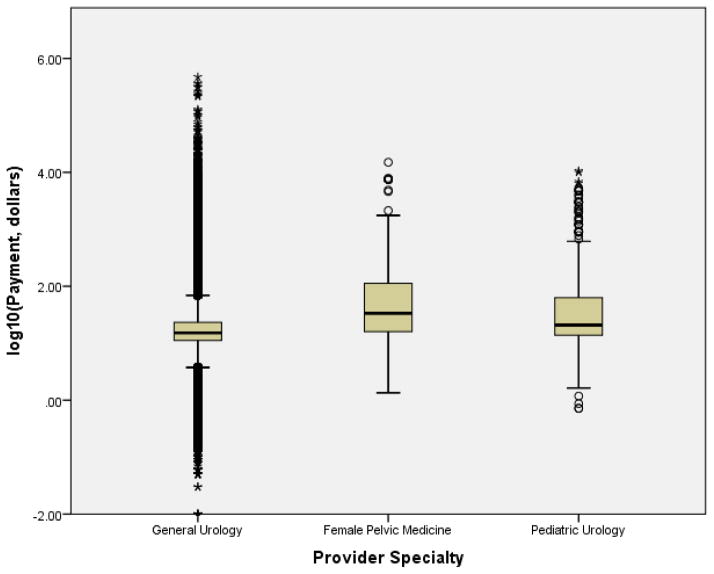

Between January 1, 2014 and December 31, 2014, a total of 235,239 non-research and non-teaching hospital payments were present in the database across 9,343 recipients (average 25 payments per recipient). The total payments were $32,450,382, ranging from a minimum payment < $1 to a maximum payment of $472,946 (Table 1). Sensitivity analysis demonstrated a reduction in total payments to $16,391,101 and $5,932,316 at 1% and 5% exclusion, respectively. Mean payments were reduced from $138 to $71 and $28, respectively. Overall median payments did not change. Payment characteristics were stratified across provider specialty, form of payment, nature of payment, ownership indicator, and dispute status. A summary of these categories and their associated payments are presented in Table 2. Amongst the different urology providers, female pelvic medicine practitioners received the highest median payment of $34 (IQR: $16–$113); the majority of payments were predominantly to General Urologists (99%).

Table 1.

Summary of CMS 2014 database characteristics

| Payment Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Number of Payments | 235,239 |

| Total Payments | $32,450,382 |

| Min/Max Payments | < $1/$472,946 |

| Mean Payments (SD) | $138 ($2,250) |

| Median Payment (IQR) | $15 ($11–$23) |

| Number of Physicians | 9,343 |

| Number of Manufacturers | 351 |

| Number of Drugs/Biologicals | 498 |

Abbreviations: CMS, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range. Dollar values denominated in U.S. dollars, rounded to the nearest dollar value.

Table 2.

Characteristics of payments in CMS 2014 database

| Characteristics | Number of payments (%) | Total payments, dollars (%) | Median payment, dollars (IQR) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Provider Specialty | |||

| General Urology | 233,751 (99) | 32,127,644 (99) | 15 (11–23) |

| Female Pelvic Medicine | 347 (< 1) | 147,567 (< 1) | 34 (16–113) |

| Pediatric Urology | 1,141 (< 1) | 175,172 (< 1) | 21 (14–63) |

|

| |||

| Form of Payment | |||

| Cash | 34,888 (15) | 23,989,439 (74) | 45 (16–350) |

| Dividend, other returns | 146 (< 1) | 898,493 (3) | 2,200 (2,200–7,300) |

| Non-cash Items and Services | 200,196 (85) | 6,770,243 (21) | 14 (11–20) |

| Stock, Options, other ownership interests | 9 (< 1) | 792,207 (2) | 24,050 (510–76,101) |

|

| |||

| Nature of Payment | |||

| Charitable Contribution | 1 (< 1) | 50 (< 1) | 50 (50–50) |

| Non-consulting Services | 3,397 (1) | 7,608,551 (23) | 2,100 (1,138–3,000) |

| Faculty/Speaking Fee, non-accredited CME | 204 (< 1) | 406,758 (1) | 1,800 (1,050–2,250) |

| Faculty/Speaking Fee, accredited CME | 1 (< 1) | 1,125 (< 1) | 1,125 (1,125–1,125) |

| Consulting Fee | 2,307 (1) | 5,360,514 (17) | 1,950 (700–2,700) |

| Ownership/Investment Interest | 4,192 (2) | 4,897,273 (15) | 400 (178–914) |

| Education | 5,963 (3) | 1,920,282 (6) | 57 (9–99) |

| Entertainment | 83 (< 1) | 3,510 (< 1) | 24 (14–46) |

| Food and Beverage | 208,414 (89) | 4,746,106 (15) | 14 (11–20) |

| Gift | 73 (< 1) | 11,253 (< 1) | 35 (12–104) |

| Grant | 15 (< 1) | 160,583 (1) | 10,000 (1,000–20,000) |

| Honoraria | 133 (< 1) | 329,825 (1) | 2,350 (1,500–3,000) |

| Royalty or License | 107 (< 1) | 3,514,777 (11) | 4,260 (493–21,098) |

| Travel and Lodging | 10,349 (4) | 3,489,778 (11) | 158 (38–362) |

|

| |||

| Ownership Indicator | |||

| No | 230,845 (98) | 28,219,842 (87) | 15 (11–23) |

| Yes | 4,394 (2) | 4,230,540 (13) | 400 (158–893) |

|

| |||

| Dispute Status | |||

| No | 235,208 (> 99) | 32,428,488 (> 99) | 15 (11–23) |

| Yes | 31 (< 1) | 21,894 (< 1) | 61 (15–572) |

Abbreviations: CMS, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; IQR, interquartile range; CME, continuing medical education. Dollar values denominated in U.S. dollars, rounded to the nearest dollar value. Cash includes cash equivalents. Percentages rounded to nearest percent.

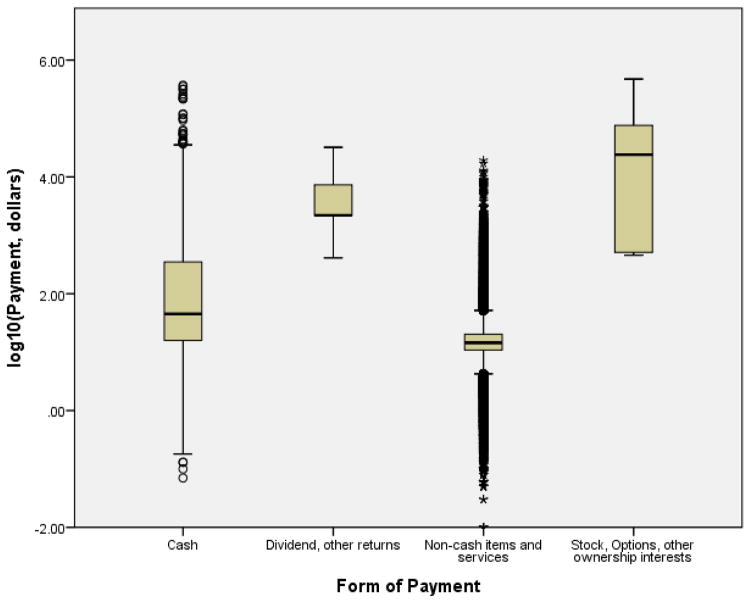

Form of Payments varied dramatically in terms of magnitude, with the highest median payments to those recipients with stock, options, other ownership interests, or dividend and other returns ($24,050 [IQR $510–$76,101] and $2,200 [IQR $2,200–$7,300], respectively). Stock, options, and other ownership interests represent a 1,603-fold difference in median payment when compared to the remainder of the database. The remainder of payments were in non-cash items and services and cash.

Within nature of payments, the majority of payments were in the food and beverage category (89%), though this constituted only 15% of the total dollar value of payments. Non-consulting fees comprised 23% of all payments despite the number of payments being only 1%. Physician ownership was a significant factor in payment medians, with a 27-fold difference between those who had equity ownership in the payer versus those who did not. Though only 31 payments (< 1% of all records) were disputed, there was a 4-fold difference between those that were disputed and those that were not.

The top ten recipients received 16% of all payments (Table 3). The data are significantly skewed towards higher payment values (Figure 1), as indicated by the large deviation between the mean and median payments ($138 vs. $15, respectively). The top 1% of payments constitutes 49% ($16,042,494) of the overall payment amount, and the top 10% constitute 87% ($28,256,003) of payments to all urology practitioners. The maximum payment was 1.5% ($472,946) of all payments, representing a 315,530-fold difference over the median. Graphical depictions using log10 transformations of payments for provider specialty, form of payment, and ownership indicator are presented in Figures 2–4.

Table 3.

Top 10 payments to urology practitioners

| Rank | Payment amount, dollars |

|---|---|

| 1 | 896,744 |

| 2 | 896,184 |

| 3 | 829,682 |

| 4 | 513,499 |

| 5 | 445,670 |

| 6 | 384,098 |

| 7 | 319,774 |

| 8 | 297,744 |

| 9 | 286,818 |

| 10 | 233,559 |

Figure 1.

Distribution of payments to urology providers

Cumulative percent of all individual payments. Total payments are $32,450,382. Top 10% of payments comprise of 87% of total payments. Top 1% of payments comprise of 49% of total payments. Payments are in U.S. dollars.

Figure 2.

Boxplot of payments to urology providers stratified by provider specialty

Log10 transformation of payments performed for visual clarity. Error bars denote 1.5x interquartile range (IQR). Mild outliers (1.5x–3x IQR) are marked with circles. Extreme outliers (>3x IQR) are marked with asterisks.

Figure 4.

Boxplot of payments to urology providers stratified by ownership interest

Log10 transformation of payments performed for visual clarity. Error bars denote 1.5x interquartile range (IQR). Mild outliers (1.5x–3x IQR) are marked with circles. Extreme outliers (>3x IQR) are marked with asterisks.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this study provides the first report on payments to urologists from industry since the inception of the Sunshine Act. A total of $32,450,382 was distributed to practitioners in an uneven distribution. The majority of payments were in the form of food and beverage. The largest categorical difference from the median was in the form of stock, options, and other ownership interests ($24,050).

In a national survey of physicians, 94% reported some form of relationship with the pharmaceutical industry8. While the majority of these involved some food in the workplace or drug samples, 28% received payments for consulting, giving lectures, or enrolling patients in trials. For the half-year spanning August to December 2013, prior reports in a variety of specialties have demonstrated similar skew to practitioner payments9–13. Across all specialties, Orthopaedic surgeons received the most in total payments ($80–100 million), roughly ten times that of Urologists during the same period9, 13. This appears to be driven by the relatively higher payments in the form of royalty and license fees. Caution should be exercised in interpretation of half-year data, however, due to seasonality (i.e., payments may be irregularly disbursed through a fiscal year). An advantage of the CMS 2014 database is that it accounts for seasonality. Cross-specialty comparisons will become more accurate with the emergence of analyses on full-year data.

While the majority of practitioners are receiving small payments in the form of food and beverage, a minority of recipients constitute 85% of the dollar-value of non-food and beverage payments. The largest payments are in the category of stock, options, and other ownership interests, which represents a 1,603-fold difference between the median payment and the remainder of the database. A related metric, the ownership indicator, represents all forms of payments to recipients with ownership interest and demonstrates a 27-fold difference in median payment. Whether or not the type of payment has any influence on prescription patterns remains to be seen, and it is unclear if the magnitude of payments is correlated to strength of influence if one exists. A single-center case control study suggested both small and large payments affect behavior; physicians who received meals and speaker fees were similarly more likely to request drug additions to hospital formularies than those who did not14. The strength of association with dollar-magnitudes was not measured. Nevertheless, if there is a linear relationship between magnitude and practice patterns, on the basis of our study one would expect the strongest correlation in the categories containing ownership stakes. One such example was highlighted in a landmark paper in the urological literature, which evaluated the usage of intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) for prostate cancer amongst self-referring urology groups15. This study noted that IMRT was prescribed more frequently in self-referral groups than in matched control groups, suggesting a financial conflict of interest. Though a subject of considerable debate5, 7, 16, it has raised awareness that compensation may have a bigger effect than once perceived. This study represents the initial steps of aggregating data to detect such effects in future studies.

Our report should be considered in the context of several limitations. First, the database consists of self-reported data from industry manufacturers and group purchasing organizations. Categorizations may be misappropriated; for example there are no categorizations for other subspecialties within urology such as Endourology, Oncology, or Reconstructive Urology. These physicians may instead be contained within General Urology, which limits cross-specialty interpretation. Though there are attempts to standardize reporting rules, loopholes have also been reported that may circumvent such requirements17. Second, the CMS requires only covered manufacturers and group purchasing organizations to report payments. Any payment to a practitioner that is outside the jurisdiction of the CMS would not be captured in this database, such as certain specialty lab tests, and therefore limits generalizability. Lastly, recipients of payments may be subject to the Hawthorne effect (i.e., observer effect), whereby individuals may modify their behaviors in response to their awareness of being observed. It is possible that potential recipients refused payments they would otherwise accept due to the knowledge of public disclosure. Despite these limitations, CMS is the single largest payer of health care in the United States, covering over 90 million Americans18, and the Open Payments database contains the most robust record of payments to care providers to date.

CONCLUSIONS

Urology practitioners received over $32 million in payments from industry in 2014, unevenly distributed across recipients. Whether this influences practice patterns or patient care remains to be seen, though the release of the CMS Open Payments 2014 database is an important first step in detecting a conflict of interest if it exists.

Figure 3.

Boxplot of payments to urology providers stratified by form of payment

Log10 transformation of payments performed for visual clarity. Error bars denote 1.5x interquartile range (IQR). Mild outliers (1.5x–3x IQR) are marked with circles. Extreme outliers (>3x IQR) are marked with asterisks. Cash includes cash equivalents.

References

- 1.Coyle SL Ethics, Human Rights Committee, A. C. o. P.-A. S. o. I. M. Physician-industry relations. Part 1: individual physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:396. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-5-200203050-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Services, C. f. M. a. M. Fact Sheet for Applicable Manufacturers [Google Scholar]

- 3.Services, C. f. M. a. M. 42 CFR Parts 402 and 403 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Services, C. f. M. a. M. The FACTS about Open Payments Data [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jacobs BL, Schroeck FR, Hollenbeck BK. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy for prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:679. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1314524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mitchell JM. Urologists’ self-referral for pathology of biopsy specimens linked to increased use and lower prostate cancer detection. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:741. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Penson DF. Re: urologists’ use of intensity-modulated radiation therapy for prostate cancer. J Urol. 2014;191:1292. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.02.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Campbell EG, Gruen RL, Mountford J, et al. A national survey of physician-industry relationships. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1742. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa064508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Samuel AM, Webb ML, Lukasiewicz AM, et al. Orthopaedic Surgeons Receive the Most Industry Payments to Physicians but Large Disparities are Seen in Sunshine Act Data. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473:3297. doi: 10.1007/s11999-015-4413-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rathi VK, Samuel AM, Mehra S. Industry ties in otolaryngology: initial insights from the physician payment sunshine act. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;152:993. doi: 10.1177/0194599815573718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harvey HB, Alkasab TK, Pandharipande PV, et al. Non-Research-Related Physician-Industry Relationships of Radiologists in the United States. J Am Coll Radiol. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2015.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang JS. The Physician Payments Sunshine Act: data evaluation regarding payments to ophthalmologists. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:656. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cvetanovich GL, Chalmers PN, Bach BR., Jr Industry Financial Relationships in Orthopaedic Surgery: Analysis of the Sunshine Act Open Payments Database and Comparison with Other Surgical Subspecialties. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97:1288. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.N.01093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chren MM, Landefeld CS. Physicians’ behavior and their interactions with drug companies. A controlled study of physicians who requested additions to a hospital drug formulary. JAMA. 1994;271:684. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mitchell JM. Urologists’ use of intensity-modulated radiation therapy for prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1629. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1201141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sartor O, Silberstein JL. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy for prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:679. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1314524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lichter PR. Implications of the Sunshine Act--revelations, loopholes, and impact. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:653. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Services, C. f. M. a. M. CMS Roadmaps Overview [Google Scholar]