Abstract

Background

Sacral neuromodulation (SNM) has emerged as a treatment option for faecal incontinence (FI). However, its objective effect on symptoms and anorectal function is inconsistently described. This study aimed to systematically review the impact of SNM on clinical symptoms and gastrointestinal physiology in patients with FI, including factors that may predict treatment outcome.

Methods

An electronic search of MEDLINE (1946–2014)/EMBASE database was performed in accordance with PRISMA guidelines. Articles that reported the relevant outcome measures following SNM were included. Clinical outcomes evaluated included: frequency of FI episodes, FI severity score and success rates. Its impact on anorectal and gastrointestinal physiology was also evaluated.

Results

Of 554 citations identified, data were extracted from 81 eligible studies. Meta‐analysis of the data was precluded due to lack of a comparison group in most studies. After permanent SNM, ‘perfect’ continence was noted in 13–88% of patients. Most studies reported a reduction in weekly FI episodes (median difference of the mean −7.0 (range: −24.8 to −2.7)) and Wexner scores (median difference of the mean −9 (−14.9 to −6)). A trend towards improved resting and squeeze anal pressures and a reduction in rectal sensory volumes were noted. Studies failed to identify any consistent impact on other physiological parameters or clinicophysiological factors associated with success.

Conclusion

SNM improves clinical symptoms and reduces number of incontinence episodes and severity scores in patients with FI, in part by improving anorectal physiological function. However, intervention studies with standardized outcome measures and physiological techniques are required to robustly assess the physiological impact of SNM.

Keywords: anorectal physiology, faecal incontinence, sacral nerve stimulation, sacral neuromodulation

Introduction

Community studies conducted in Australia1, 2 and New Zealand3 have identified faecal incontinence (FI) in approximately 11% of subjects, meaning that 3 million people across the two nations suffer with this condition. However, its true prevalence is likely to be higher, as it remains an underdiagnosed problem.4 Furthermore, up to 40% of sufferers report severe impact on quality of life and emotional well‐being.5 Until recently, surgical treatment of this condition was limited to a few (often morbid) procedures with limited long‐term success.6 However, sacral neuromodulation (SNM) has provided an additional option for sufferers since 1995.7

SNM is based on the premise that stimulation of the sacral nerves will restore full continence or markedly improve symptoms. However, its true clinical efficacy in large samples of patients and the rates of perfect continence achieved remains uncertain. Similarly, the mechanism of action of SNM remains unclear. Previously, the implicit assumption7 was that SNM exerted its effect via augmentation of anal pressures. However, given its efficacy in patients with sphincter defects, its action is likely to be, at least in part, extrasphincteric. Indeed, the possibility of central neuromodulation via spinal afferent fibres has been suggested.8 Over the past two decades, several systematic reviews8, 9, 10, 11 have been performed on this topic. However, some contain important limitations due to small sample size9, 12 and inclusion and analysis of disparate studies of variable quality.13 Therefore, the aim of this study was to provide a comprehensive and contemporary systematic review of the published studies on the impact of SNM on clinical outcomes (subjective and objective) and gastrointestinal (i.e. anorectal, colonic, small bowel and gastric) physiology in patients with FI. In addition, studies were reviewed for factors/clinicophysiological parameters associated with clinical success both in the short (trial phase) and long term.

Methods

A systematic review of SNM for FI was performed by conducting an electronic search of MEDLINE database (1946–November 2014) in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines.14 The search keywords used (and combined using Booleans operators) included: electrical stimulation therapy, electric stimulation, sacral nerve, sacral nerve stimulation, sacral nerve modulation, sacral neuromodulation, faecal incontinence, fecal incontinence, soiling, bowel dysfunction, bowel seepage, defecation, anal canal, anal incontinence, constipation, evacuatory dysfunction, gastrointestinal motility, gastric emptying, small intestine and urinary incontinence. In addition, the Cochrane Database and Embase (1966–2014) were also searched for relevant articles. The reference lists of all included articles were also scrutinized for relevant studies.

Inclusion criteria

All published studies reporting clinical or physiological outcomes after SNM for FI performed in adults were included. All eligible studies required an intervention in the form of either percutaneous nerve evaluation (PNE, i.e. the trial phase) and/or permanent implantation. Eligible articles also included those analysing clinicophysiological factors that were associated with success or failure of SNM for FI. Patients with scleroderma were also included as such patients were often included in studies.

Exclusion criteria

Studies where SNM was performed for urinary incontinence, constipation/evacuatory dysfunction and FI secondary to organic pathologies (e.g. complete spinal cord injury, cauda equina syndrome, congenital anorectal abnormalities, Crohn's disease and radiation proctitis) were excluded. Technical studies, or those where non‐standard SNM parameters were used or where patients had tried other forms of sacral neuromodulation (e.g. transcutaneous), were also excluded. Non‐English studies, abstracts, non‐peer reviewed studies, commentaries, letters or records where baseline data for the patients were not provided for analysis and those where outcomes of interest were not reported were also considered ineligible. Furthermore, studies performed on rectal tissue or blood flow and those performed on animals were also excluded.

Study quality assessment

As most studies were published case series, quality assessment was assessed using the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, Quality Assessment for Case Series (QACS) tool (http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg3/resources/appendix‐4‐quality‐of‐case‐series‐form2) by scoring the studies out of a maximum of eight. A study scored 1 point each if (i) it was multicentre; (ii) hypothesis/aim/objective were clearly reported; (iii) outcomes were defined; (iv) inclusion and exclusion criteria were stated; (v) data were collected prospectively; (vi) patients were recruited consecutively and (vii) the main findings of the study were clearly described; and (viii) outcomes were stratified.

Study outcomes

Clinical outcomes of interest included: (i) improvement in symptoms reported in the form of bowel chart diary (FI episodes over a period of time); (ii) changes in objective and validated FI severity scores using either Wexner/Cleveland15 or Vaizey/St Marks16 scoring systems; (iii) overall rate of success (defined as >50% improvement in FI symptoms compared with baseline); and (iv) proportion of subjects who achieved perfect continence. This overall success rate, while somewhat arbitrary, has recently been endorsed in a consensus statement17 and validated in a study of patients with FI.18 It is based on observation of an improvement in FI symptoms using symptom diaries kept by the patient before and during intervention. Symptoms evaluated include: number of incontinence episodes, faecal urgency, use of pads and impact on lifestyle. Other definitions and outcomes used in this review included: (i) intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis, which is based on measuring outcome based on the number of patients initially enrolled in the treatment as opposed to (ii) per protocol analysis (PPA), which only measures the final outcome based on the number of patients who had a successful PNE and then went on to receive a permanent implant. Primary failure is defined as those who never had a clinical response to PNE, while secondary failure, refers to those patients who had a successful response to PNE but failed to subsequently achieve therapeutic benefit from the permanent implant. Physiological outcomes of interest included: (i) anorectal, specifically anal pressures (maximum resting and squeeze pressure (mmHg)); (ii) rectal sensory thresholds (balloon volumes in millilitres of air or water), where all reported pressures in cmH2O were converted to mmHg; (iii) small/large bowel motility; and (iv) gastric emptying. Additionally, clinicophysiological factors associated with a successful response to SNM were determined.

Data extraction

Quantitative data were extracted by two independent reviewers (NM/YS) and results were cross‐checked. Any discrepancies in results were resolved by repeat data extraction, discussion and further review of the index study.

Data analysis

Given the variable reporting of results (in means and medians) and/or the fact that majority of studies lacked a control group, meta‐analysis of the data was precluded. As such, the results from each study are presented in a summarized and aggregate form. Summary results were reported as the median value of the mean differences or the median value of the median differences for each outcome (e.g. FI episodes, Wexner incontinence severity scores, anal pressures and rectal balloon volumes) pre and post SNM.

Results

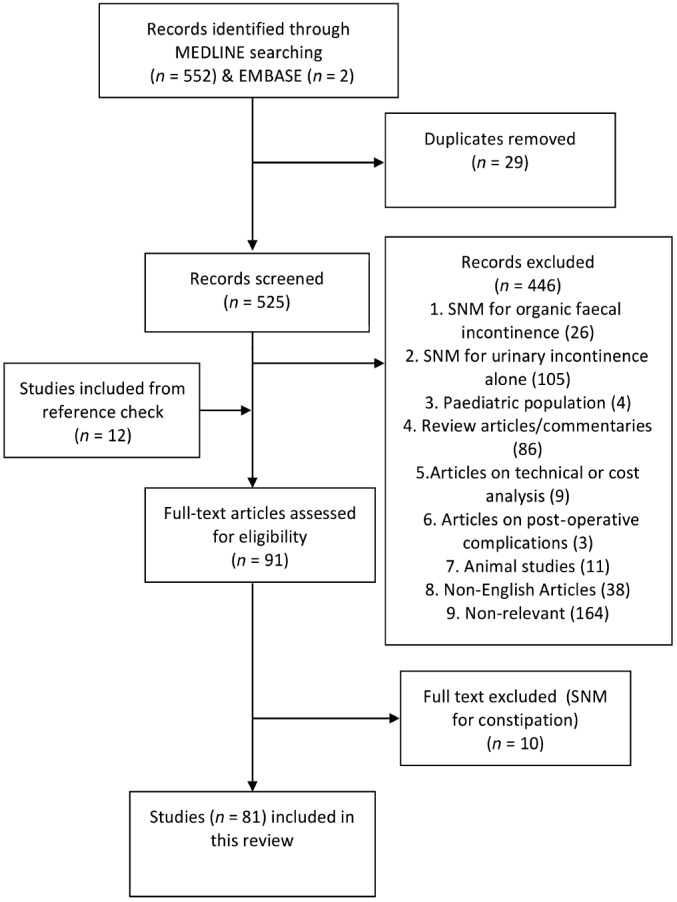

The initial electronic search revealed 552 citations. Two additional articles were identified using the EMBASE search engine.19, 20 The title and abstract of each were screened and ineligible studies were excluded. Full‐text review and cross‐reference check was then performed on 91 citations (Fig. 1), which identified 81 citations eligible for inclusion in this study. For studies where multiple publications were performed on the same cohort of patients, the shortest and the longest follow‐up results of these cohorts were included.21, 22

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the systematic review process as per PRISMA 2009 guidelines.

Study characteristics and limitations

Only one randomized trial23 and two cross‐over studies24 were identified with all remaining studies comprising of prospective case series (n = 42), retrospective case series (n = 14), cross‐sectional (n = 2) and one experimental design (Table 1, Table S1). The median QACS score for study quality was 5 (range 3–8). Most of the studies were European (n = 71) followed by equal number of publications from Australia and the United States. The sample size and follow‐up periods were heterogeneous with a median sample size of 27 (range 2–200) and a median follow‐up period of 23 months (range 2 weeks–118 months). The majority of the patients participating in the studies were female (median percentage of 90.5%).

Table 1.

Impact of sacral neuromodulation on clinical outcomes (mean values)

| Study | Design | Sample size (n) | PNE success (%) | % Female | Age, years | Follow‐up, median (months) | Wexner score | Difference | FI episodes per week | Difference | QACS score | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | ||||||||||

| Abdel‐Halim et al.25 | PCS | 23 | 69.6 | NR | 49 | NR | 14.1 | 6.3 | 7.8 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 6 |

| Altomare et al.26 | PCS | 32 | 64 | 83 | 58 | 74 | 15 | 6 | 9 | 0.6†† | 0.2 | NA | 5 |

| Altomare et al.26 | — | 10 | — | NR | — | — | 15 | 3 | 12 | 0.8†† | 0.1 | NA | — |

| Benson‐Cooper et al.20 | PCS | 29 | 93 | 82.7 | 60 | 10.7 | NR | — | 7.3 | 1 | 6.3 | 4 | |

| Chan and Tjandra27 (sphincter defect) | PCS | 21 | 88 | 73.6 | 63.4† | 12 | 15.7 | 1 | 14.7 | 13.8 | 5 | 8.8 | 7 |

| Chan and Tjandra27 (intact sphincter) | — | 32 | — | — | — | — | 16.2 | 1.3 | 14.9 | 6.7 | 2 | 4.7 | — |

| Ganio et al.28 | RCS | 16 | NA | 75 | 51.4 | 15.5 | OS | — | 11.5§ | 0.6 | NA | 4 | |

| Ganio et al.29 | PCS | 23 | 89.47 | 78.2 | NR | 54.9 | NR | — | 5.5 | 1.5 | 4 | 4 | |

| Ganio et al.30 | PCS | 28 | 83 | 78.57 | 50.2 | 1 | NR | — | 8.1 | 1.7 | 6.4 | 6 | |

| El‐Gazzaz et al.31 | XS | 24 | UD | 100 | 56.5 | 29.5 | 12 | 4.7 | 7.3 | — | — | 4 | |

| Hollingshead et al.32 | PCS | 118 | 77 | UD | UD | 21.5 | 15 | 9 | 6 | 8.5 | 1.3 | 7.2 | 4 |

| Hull et al.22 | PCS | 133 | 90 | 83 | 60.5 | 60 | NR | — | 9.1 | 1.7 | 7.4 | 8 | |

| Jarrett et al.33 | PCS | 13 | 92 | 61 | 58.5 | 12 | NR | — | 9.3 | 2.4 | 6.9 | 5 | |

| Kenefick et al.34 | PCS | 5 | 80 | 100 | 61 | 24 | NR | — | 14 | 0.5 | 13.5 | 4 | |

| Leroi et al.35 | PCS | 11 | 73 | 73 | 51.6 | 6 | NR | — | 3.2 | 0.5 | 2.7 | 5 | |

| Matzel et al.36 | PCS | 37 | 92 | 89 | 54.3 | 23.9 | NR | — | 16.4 | 2 | 14.4 | 6 | |

| Matzel et al.37 | PCS | 6 | — | 83 | — | 24 | 17 | 2.2 | 14.8 | NR | — | 3 | |

| McNevin et al.38 | PCS | 33 | 88 | 91 | 63 | NR | NR | — | 19§ | 3 | NA | 4 | |

| Melenhorst et al.39 | PCS | 134 | 75 | 87 | 55† | 25.5 | NR | — | 31.3¶ | 4.8 | NA | 4 | |

| Melenhorst et al.40 (intact sphincter) | RCS | 20 | 80 | 98 | 53.95 | 24 | NR | — | 26.6¶ | 12.5 | NA | 5 | |

| Melenhorst et al.40 (sphincter defect) | — | 20 | — | — | — | — | NR | — | 24.9¶ | 4.1 | NA | — | |

| Otto et al.41 | RCS | 14 | UD | 64 | 61† | 6 | 16.3 | 9.6 | 6.7 | NR | — | 5 | |

| Patton et al.42 | PCS/X‐over | 11 | 80 | 91 | — | 3 | 14.8‡ | 5.6 | NA | NR | — | NA | |

| Ratto et al.43 | RCS | 10 | 100 | 100 | 60.7 | 33 | 18.3 | 9.7 | 8.6 | 25.6 | 0.8 | 24.8 | 5 |

| Roman et al.44 | PCS | 18 | UD | 94 | 58.5 | 3 | 14.9 | 4.9 | 10 | NR | — | 5 | |

| Sheldon et al.45 | EXP | 10 | 75 | 100 | 51.3 | 0.5 | 16.9‡ | 10.6 | NA | 20§ | 7 | NA | NA |

| Tjandra et al.23 | RCT | 60 | 88 | 92 | 63.9† | 12 | 16 | 1.2 | 14.8 | 9.5 | 3.1 | 6.4 | NA |

| Vaizey et al.24 | X‐over | 2 | UD | 100 | 63 | 2 weeks | NR | — | 20 | 1 | 19 | N/A | |

| Wexner et al.21 | PCS | 133 | 90 | 83 | 60.5 | 28 | NR | — | 9.4 | 1.9 | 7.5 | 7 | |

| Wong et al.46 | PCS | 91 | 67 | 97 | 63 | 31 | 14.3 | 7.6 | 6.7 | NR | — | 5 | |

| Median | — | 22 | 83 | 87 | 58.5 | 21.5 | 15.7 | 5.6 | 9 | 12.7 | 1.8 | 7.0 | 5 |

| Minimum | — | 2 | 64 | 61 | 49 | 0.5 | 12 | 1 | 6 | 3.2 | 0.5 | 2.7 | 3 |

| Maximum | — | 134 | 100 | 100 | 63.9 | 60 | 18.3 | 10.6 | 14.9 | 31.3 | 12.5 | 24.8 | 8 |

†Mean values. ‡Vaizey score. §FI/2 weeks. ¶FI/3 weeks. ††FI/day. EXP, experimental study; FI, faecal incontinence; NA, not applicable; NR, not reported; OS, other score; PCS, prospective case series; PNE, percutaneous nerve evaluation; QACS, quality assessment for case series (max 8); RCS, retrospective case series; RCT, randomized controlled trial; UD, undefined; X‐over, cross‐over study; XS, cross‐sectional study.

Impact on clinical outcomes

Clinical outcome data were obtained from 63 studies. Large variability in reporting of outcomes was found with results presented as means, medians and incontinence episodes over a variable number of weeks reported (Table 1, Table S1). Forty studies reported outcomes using objective incontinence severity scores, with the vast majority using the Cleveland Clinic (Wexner) score, although six studies used the Vaizey/St Mark's scoring system and two applied other measures. Eighteen studies reported rates of ‘perfect continence’.

Overall, there was improvement in subjective and objective measures of FI across all studies, irrespective of study design. FI episodes per week was used as an outcome measure in 23 studies, FI episodes per 2 weeks in seven studies, per 3 weeks in 10 studies and per day in two studies. Among the studies reporting on weekly incontinence rate, the median reduction of the mean and the median value of FI episodes was 7.0 (range 2.7–24.8) and 8 (range 3–13.3), respectively (Table 1, Table S1). Similarly, there was improvement in objective FI severity scores with a median of the mean and median reduction in the Wexner scores across the 32 studies being 9 (range 6–14.9) and 8 (2.4–14), respectively. The PNE success rate, defined as >50% reduction in clinical symptoms over the evaluation period, ranged from 51.5 to 100%, with a median value of 81% on a per protocol basis. The reported rates of ‘perfect continence’ ranged from 13 to 88% (Table 2). Notwithstanding the inevitable heterogeneity of patient characteristics, pooling of these results (n = 608) gave a perfect continence rate of 36.5% on an ITT basis and 42.9% on a PPA.

Table 2.

Details of patients achieving full continence in 18 studies

| Study identification | Sample size (n) | Number responding to sacral neuromodulation (n) | Number achieving full continence (n) | % Full continence (per protocol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leroi et al.†, 47 | 34 | 34 | 5 | 15 |

| Leroi et al.35 | 9 | 8 | 1 | 13 |

| Altomare et al.†, 26 | 52 | 38 | 9 | 24 |

| Oom et al.77 | 46 | 37 | 8 | 22 |

| Boyle et al.48 | 50 | 37 | 13 | 35 |

| Hull et al.22 | 72 | 64 | 26 | 41 |

| Oz‐Duyos et al.49 | 47 | 28 | 14 | 50 |

| Matzel et al.36 | 37 | 37 | 12 | 32 |

| Jarret et al.50 | 59 | 46 | 19 | 41 |

| Tjandra et al.23 | 59 | 54 | 25 | 46 |

| Ganio et al.30 | 25 | 22 | 11 | 50 |

| George et al.51 | 25 | 23 | 12 | 52 |

| Matzel et al.7 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 67 |

| Santoro et al.52 | 28 | 28 | 19 | 68 |

| Kenefick et al.53 | 15 | 15 | 11 | 73 |

| Kenefick54 | 19 | 19 | 14 | 74 |

| Ganio et al.29 | 19 | 17 | 14 | 82 |

| Vaizey et al.55 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 88 |

| Total | 608 | 518 | 222 |

Pooled

‡

: 36.5%

Range: 13–88% ‡ |

Data after permanent implant only.

Intention‐to‐treat analysis (patient with perfect continence/total sample size). Per protocol analysis = 42.9%.

The only prospective randomized study compared best conservative management to SNM in 120 patients over a period of 12 months and conclusively demonstrated the clinical efficacy of the treatment arm with improvement in subjective and objective measures of FI.23 Similarly, Leroi et al.,47 in a randomized case cross‐over study of 24 patients, reported significant improvement in clinical symptoms during the stimulation period. The only other case cross‐over study by Vaizey et al.24 was limited by its small sample size of n = 2.

Impact on gastrointestinal physiology

Anorectal

The impact on anorectal physiological parameters was reported in 37 studies (Table 3, Table S2). The methodological heterogeneity of techniques used and measurements recorded during anorectal manometry was a significant issue when summarizing data. However, a consistent trend was noted in most studies, with an increase in both maximum resting pressure and squeeze pressure after SNM with a median difference of the mean of 5.9 (−11.8–21) and 14.8 mmHg (−12.5–96), respectively (Table 3). No correlation could be made between manometric findings and clinical symptoms after stimulation as most results were not grouped based on outcome. Rectal sensitivity, as measured by the volume required to elicit sensory thresholds, tended to improve (as evidence by a reduction in sensory threshold volumes) after SNM. The median reduction of the mean values for sensory volumes was 11.9, 16.4 and 6.6 mL for first sensation, sensation of urge and maximum tolerated volume, respectively (Table 3). The median values are shown in Table S2. The effect of SNM on rectal compliance was measured in seven studies,25, 29, 35, 44, 55, 58, 59 but none of these showed any statistically significant changes, although the sample size in each study was small ranging from 11 to 23 patients. Other rectal physiological parameters such as rectal stool retention test, rectoanal angle and rectal motility was not affected by SNM.59, 60 However, Michelsen et al.61 demonstrated a significant decrease in postprandial rectal tone during stimulation.

Table 3.

Impact of sacral neuromodulation on anorectal physiology (mean values)

| Study | Anal resting pressurea | Difference | Anal squeeze pressurea | Difference | First perception (mL) | Difference | Urge volume (mL) | Difference | Maximum tolerated volume (mL) | Difference | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | ||||||

| Altomare et al.26 | 45 | 56 | 11 | 50 | 118 | 68 | 61 | 38 | −23 | 134 | 110 | −24 | 206 | 169 | −37 |

| Altomare et al.26 | 34 | 56 | 21 | 42 | 134 | 92 | 61 | 58 | −3 | 120 | 119 | −1 | 170 | 175 | 5 |

| Chan and Tjandra56 (sphincter defect) | 31.3 | 30.9 | −0.4 | 58.4 | 62.4 | 4 | NR | — | — | NR | — | — | NR | — | — |

| Chan and Tjandra56 (intact sphincter) | 28.6 | 29.6 | 1 | 63.1 | 69 | 5.9 | NR | — | — | NR | — | — | NR | — | — |

| Ganio et al.28 | 38 | 49 | 11 | 67 | 83 | 16 | 61 | 49 | −12 | 118 | 87.7 | −30.3 | NR | — | — |

| Ganio et al.29 | 39 | 54 | 15 | 83 | 90 | 7 | 61 | 49 | −12 | 112 | 92 | −20 | NR | — | — |

| Ganio et al.30 | 39 | 54 | 15 | 85 | 99 | 14 | 58.5 | 37 | −21.5 | 112 | 92 | −20 | NR | — | — |

| George et al.51 | 21.9 | 23.0 | 1.1 | 36.6 | 35.6 | −0.96 | 56.7 | 54.7 | −2 | 122 | 90 | −32 | 178 | 123 | −55 |

| Jarrett et al.50 | 33.8 | 36.0 | 2.2 | 45.6 | 68.4 | 22.8 | 41 | 27 | −14 | 92 | 71 | −21 | 129 | 107 | −22 |

| Kenefick et al.53 | 25.7 | 30.2 | 4.4 | 31.6 | 50.8 | 19.1 | NR | — | — | 82 | 74 | −8 | 127 | 103 | −24 |

| Leroi et al.35 | 56.6 | 44.9 | −11.8 | 41.6 | 29 | −12.5 | 175 (123.7) | — | −51.3 | — | — | — | 202.5 | 200 | −2.5 |

| Matzel et al.7 | NR | — | — | 66 | 162 | 96 | NR | — | — | NR | — | — | NR | — | — |

| Matzel et al.37 | NR | — | — | 48.5 | 92.7 | 44.2 | NR | — | — | NR | — | — | NR | — | — |

| Melenhorst et al.40 (intact sphincter) | NR | — | — | NR | — | — | 50.8 (38.9) | — | −11.9 | 96.1 | 83.3 | −12.8 | 164 | 153.3 | −10.7 |

| Melenhorst et al.40 (sphincter defect) | NR | — | — | 88.6 | 125.3 | 36.7 | 35.5 (25) | — | −10.5 | 59.8 | 75 | 15.2 | 125.5 | 139.1 | 13.6 |

| Ratto et al.43 | 69.6 | 75.9 | 6.3 | 30.3 | 35.5 | 5.2 | 50.2 (50.5) | — | 0.3 | 79 | 90 | 11 | 136 | 133.5 | −2.5 |

| Ripetti et al.57 | 59 | 74 | 15 | 89 | 110 | 21 | 80 (39) | — | −41 | 127 | 89 | −38 | NR | — | — |

| Roman et al.44 | NR | — | — | NR | — | — | 44 (71) | — | 27 | — | — | — | 227 | 201 | −26 |

| Sheldon et al.45 | 48.6 | 49.3 | 0.7 | NR | — | — | 40 (32) | — | −8 | 71 | 68 | −3 | 100 | 105 | 5 |

| Tjandra et al.23 | 29.7 | 30.1 | 0.4 | 61.2 | 66.3 | 5.1 | NR | — | — | NR | — | — | NR | — | — |

| Vaizey et al.24 | 27.6 | 42.3 | 14.7 | 73.6 | 69.9 | −3.7 | NR | — | — | NR | — | — | NR | — | — |

| Otto et al.41 | 33.8 | 39.7 | 5.9 | 86.5 | 101.3 | 14.8 | 62.1 | 86.4 | 24.3 | 108.2 | 145.7 | 37.5 | 148.9 | 188.2 | 39.3 |

| Median | 34 | 44.9 | 5.9 | 61.2 | 83 | 14.8 | 58.5 | 49 | −11.9 | 110.1 | 89.5 | −16.4 | 156.5 | 146.2 | −6.6 |

| Minimum | 21.9 | 23 | −11.8 | 30.3 | 29 | −12.5 | 35.5 | 25 | −51.3 | 59.8 | 68 | −38 | 100 | 103 | −55 |

| Maximum | 69.6 | 75.9 | 21 | 89 | 162 | 96 | 175 | 123.7 | 27 | 134 | 145.7 | 37.5 | 227 | 201 | 39.3 |

Maximum pressure in mmHg. NR, not reported.

Other gastrointestinal organs

Two studies investigated the impact of SNM on gastric motility and emptying rate.62, 63 In both studies, a randomized cross‐over design was employed but only one was double‐blinded.63 A washout period of 1 week was used in one62 and not the other. No consistent changes were observed in gastric motility and emptying or small bowel motility during stimulation as assessed using a magnetic tracking system and scintigraphic methods. No consistent impact of SNM on colonic transit was identified in the three studies that investigated its effect in patients with FI.63, 64, 65 Baseline data were available only in the studies by Michelsen et al.64 and Uludag et al.,65 whereas Damgaard et al.63 turned off the stimulator in a randomized cross‐over design. Michelsen et al. showed that colonic transit times were increased after SNM and that there was a decrease in antegrade transport from the ascending colon and an increase retrograde transport from the descending colon. Similarly, Patton et al.42 used high‐resolution colonic manometry and observed that SNM alters colonic motility by increasing retrograde propagating sequences in the left colon.

Factors associated with successful clinical response to SNM

Fourteen studies sought to determine factors predictive of outcome following subchronic (PNE) and chronic stimulation using Interstim pulse generators (IPGs) (Table S3). The factors investigated varied across studies but included (i) patient factors, such as baseline demographics (age, sex, body mass index, baseline quality of life scores) and anorectal physiological parameters (anal resting and squeeze pressures, anal electrosensation, rectal sensation, pudendal nerve terminal motor latency, anal electromyography); (ii) disease factors, such as aetiology and severity of incontinence and previous treatments (e.g. biofeedback); (iii) technical factors, such as type of leads, site of insertion, intraoperative motor and sensory responses and stimulation parameters. Only a small number of factors were associated with outcome and are shown in Table S3. Notably, age was a significant variable in more than one study66, 67 and the younger the patient (<70 years old), the more likely a successful response to SNM, although Feretis et al.19 found that older age was associated with success. Anal sphincter defects and multiple PNE procedures were correlated with failures of SNM in two studies.68, 69 The variables that were not predictive of outcome included (not shown in table): baseline anorectal physiological parameters and colonic transit study, body mass index, gender, stimulation parameters, aetiology of FI (idiopathic versus organic), baseline quality of life, duration and severity of FI and presence of anxiety or depression. The primary and secondary failure rates of SNM across these studies were 31.5 and 17.4%, respectively.

Discussion

SNM has been used extensively in the management of FI over the past 20 years. In this systematic review, the impact of SNM on clinical symptoms and objective FI severity scores was investigated in the summative data analysis. Generally, most studies were of poor quality (case series) with only one randomized controlled trial and two cross‐over studies; the sample sizes and follow‐up periods were heterogeneous. The median reduction of FI episodes per week was 7–8 (2.7–24.8) and objective FI score (Wexner) was 8–9 (2.5–14.9). Overall, the PNE success rate ranged from 51.5 to 100%, with a median value of 81%. Of the patients who responded to the trial phase, up to 43% achieved full continence, at least in the short term. The impact of SNM on anorectal physiology was variable. However, there appeared to be a trend towards improved anal pressures (as evidenced by increased resting and maximum squeeze pressures) and rectal sensitivity (as evidenced by a decrease in sensory threshold volumes). However, no consistent changes on other rectal or other gastrointestinal physiological parameters were evident and no robust clinical or physiological factors were identified that could reliably predict success following SNM, although the age of the patient and the integrity of the anal sphincter complex may be of importance.

The clinical efficacy of SNM as shown in this review is similar to other systematic reviews.13 The median reduction of FI episodes per week reported by Thin et al.11 was 7, consistent with the findings of the present review. The use of FI severity scores is able to more objectively assess the impact of SNM on clinical symptoms. All but six studies used the Cleveland Clinical (Wexner) FI scores for this purpose and significant reductions in scores were evident, suggesting objective clinical improvement. However, this scoring system does not incorporate improvement in symptoms of faecal urgency or reduction in use of constipating medications and may underestimate the clinical efficacy of SNM. Furthermore, FI is a complex disorder with varied symptom repertoire. Accordingly, current measures to assess outcome (including the Wexner incontinence score) may not be sophisticated enough to comprehensively assess outcome. Moreover, they may fail to capture how patients change their lifestyles to manage their symptoms (e.g. being close to the toilet).

In terms of the impact of SNM on anorectal physiology, this review was able to demonstrate a trend towards an increase in anal pressures and improved rectal sensation (reduced sensory threshold volumes), consistent with other studies.13 Increasingly, rectal reservoir dysfunction is appreciated as an important factor in the development of FI.70 Traditionally, patients with FI are frequently noted to have rectal hypersensitivity (heightened awareness of distension) and are only able to tolerate small volumes during rectal distension.71 However, rectal hyposensitivity, which by contrast is characterized by reduced awareness of distension and the ability to tolerate large volumes during rectal distension, is also considered important in the pathophysiology of FI in some patients.72, 73 The fact that this review identified a tendency for rectal sensory threshold volumes to decrease rather than increase following SNM suggests that reduced sensory threshold volumes (i.e. rectal hypersensitivity) was not the predominant abnormality in the patients selected for SNM in the majority of studies. However, patients were not stratified on the basis of rectal sensory function in most studies and thus further evaluation is required before any definitive conclusions can be drawn. This may be pertinent as patients with abnormal rectal sensitivity are likely to demonstrate a favourable response to SNM.74 The studies assessing rectal compliance before and after SNM revealed no significant differences following SNM, suggesting that modulation of afferent nerve pathways rather than alteration of rectal biomechanics may account for the changes in rectal sensitivity noted.75

The influence of SNM on the colon, small bowel and stomach has been explored in several studies. Although no consistent impact was noted on gastric emptying or small bowel motility, such studies have suffered from small sample sizes, lack of baseline data and the possibility of carry over effect upon turning the stimulation off.62, 63 The impact of SNM on colonic motility deserves further evaluation in future studies, as several studies have noted a decrease in antegrade activity originating in the ascending colon and an increase in retrograde activity from the descending colon.42, 64 Consequently, it has been suggested that this change in colonic activity following SNM creates a ‘physiological brake’ that prevents the delivery of stool to the (functionally suboptimal) anorectal unit and thus reduces incontinent episodes.

Despite multiple studies exploring various factors, prognostic indicators of success remain elusive. In fact, the most recent publication exploring this question in 60 patients76 including the randomized study by Tjandra et al.23 failed to identify any factors predictive of outcome. Currently, the response observed during the trial stimulation (PNE) is most useful in predicting outcome following insertion of the permanent implant. However, the rate of secondary failure of up to 17%, as seen in this review, suggests that the response to the trial stimulation does not predict long‐term outcome when faced with a progressive disease such as FI. Other significant factors associated with therapeutic long‐term outcomes across the studies included young age at implant, improvement in symptoms of faecal urgency, neurogenic FI, a loose stool consistency at baseline, low threshold stimulation voltage, more severe FI and low rectal perception volume to urge.

The studies included in this systematic review are limited by their quality and are subject to publication bias (in favour of publishing positive results only). However, performing double‐blinded, randomized crossover studies to evaluate SNM in a large sample is difficult for various reasons: (i) after insertion of the implant, optimization of stimulation parameters is often necessary to establish efficacy; (ii) blinding is challenging as most patients are aware when they are being ‘stimulated’, even at subsensory levels; (iii) the ‘carry over’ effect of SNM has not extensively been explored; and (iv) patient recruitment is difficult as most patients are reluctant to participate in a trial involving ‘sham’ stimulation with risk of symptom deterioration/recurrence. Accordingly, well‐planned long‐term observational studies may provide useful contributions to the literature on the topic. Lack of a meta‐analysis further reduced the quality of the quantitative analysis provided in this review. Although Tan et al.13 performed a comprehensive meta‐analysis in 2011 of various outcomes of SNM, the appropriateness is questionable as a meta‐analysis of data points from case series compromises the accuracy of the results.

In conclusion, despite the poor quality of studies published, SNM appears to be clinically efficacious with up to 42% achieving full continence and the majority experiencing improvement in symptoms. Its impact on gastrointestinal physiology remains poorly understood and thus there is a need for more robust scientific investigations on the mechanism of action of SNM and its predictive factors. Given the low morbidity, reversibility and minimal invasiveness of this procedure, the results provided by SNM therapy supersedes other surgical interventions for FI.

Supporting information

Table S1 Impact of sacral neuromodulation on clinical outcomes (median values).

Table S2 Impact of sacral neuromodulation on anorectal physiology (median values).

Table S3 Significant factors associated with sacral neuromodulation clinical outcome.

Acknowledgements

NM is supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council Postgraduate and Royal Australasian College of Surgeons Foundation of Surgery Research Scholarships.

N. Mirbagheri MBBS (Hons), FRACS; Y. Sivakumaran MBBS (Hons); N. Nassar PhD; M. A. Gladman PhD, MRCOG, FRCS (Gen Surg), FRACS.

This paper was presented in part at the Surgical Research Society 50th Annual Meeting, November 2013, Adelaide, SA, Australia.

References

- 1. Kalantar JS, Howell S, Talley NJ. Prevalence of faecal incontinence and associated risk factors; an underdiagnosed problem in the Australian community? Med. J. Aust. 2002; 176: 54–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ng KS, Nassar N, Hamd K, Nagarajah A, Gladman MA. Prevalence of functional bowel disorders and faecal incontinence: an Australian primary care survey. Colorectal Dis. 2014; 17: 150–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sharma A, Marshall RJ, Macmillan AK, Merrie AE, Reid P, Bissett IP. Determining levels of fecal incontinence in the community: a New Zealand cross‐sectional study. Dis. Colon Rectum 2011; 54: 1381–1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Johanson JF, Lafferty J. Epidemiology of fecal incontinence: the silent affliction. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 1996; 91: 33–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brown HW, Wexner SD, Segall MM, Brezoczky KL, Lukacz ES. Quality of life impact in women with accidental bowel leakage. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2012; 66: 1109–1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gladman MA, Knowles CH. Surgical treatment of patients with constipation and fecal incontinence. Gastroenterol. Clin. North Am. 2008; 37: 605–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Matzel KE, Stadelmaie U, Gall FP, Hohenfellner M. Electrical stimulation of sacral spinal nerves for treatment of faecal incontinence. Lancet 1995; 346: 1124–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Carrington EV, Evers J, Grossi U et al A systematic review of sacral nerve stimulation mechanisms in the treatment of fecal incontinence and constipation. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2014; 26: 1222–1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jarrett ME, Mowatt G, Glazener CM et al Systematic review of sacral nerve stimulation for faecal incontinence and constipation. Br. J. Surg. 2004; 91: 1559–1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Carrington EV, Knowles CH. The influence of sacral nerve stimulation on anorectal dysfunction. Colorectal Dis. 2011; 13 (Suppl. 2): 5–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Thin NN, Horrocks EJ, Hotouras A et al Systematic review of the clinical effectiveness of neuromodulation in the treatment of faecal incontinence. Br. J. Surg. 2013; 100: 1430–1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mowatt G, Glazener C, Jarrett M. Sacral nerve stimulation for faecal incontinence and constipation in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2006; (1): CD004464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tan E, Ngo NT, Darzi A, Shenouda M, Tekkis PP. Meta‐analysis: sacral nerve stimulation versus conservative therapy in the treatment of faecal incontinence. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 2011; 26: 275–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J et al The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta‐analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ 2008; 339: b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Marcio J, Jorge N, Wexner SD. Etiology and management of fecal incontinence. Dis. Colon Rectum 1993; 36: 77–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Vaizey CJ, Carapeti E, Cahill JA, Kamm MA. Prospective comparison of faecal incontinence grading systems. Gut 1998; 44: 77–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Maeda Y, O'Connell PR, Lehur PA, Matzel KE, Laurberg S, European SNS Bowel Study Group. Sacral nerve stimulation for faecal incontinence and constipation: a European consensus statement. Colorectal Dis. 2015; 17: O74–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sanchez JE, Brenner DM, Franklin H, Yu J, Barrett AC, Paterson C. Validity of the ≥50% response threshold in treatment with NASHA/Dx injection therapy for fecal incontinence. Clin. Transl. Gastroenterol. 2015; 6: e70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Feretis M, Karandikar S, Chapman M. Medium‐term results with Sacral Nerve Stimulation for management of faecal incontinence, a single centre experience. Interv. Gastroenterol. 2013; 3: 82–88. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Benson‐Cooper S, Davenport E, Bissett IP. Introduction of sacral neuromodulation for the treatment of faecal incontinence. N. Z. Med. J. 2013; 126: 47–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wexner SD, Coller JA, Devroede G et al Sacral nerve stimulation for fecal incontinence. Ann. Surg. 2010; 251: 441–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hull T, Giese C, Wexner SD et al Long‐term durability of sacral nerve stimulation therapy for chronic fecal incontinence. Dis. Colon Rectum 2013; 56: 234–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tjandra JJ, Chan MK, Yeh CH, Murray‐Green C. Sacral nerve stimulation is more effective than optimal medical therapy for severe fecal incontinence: a randomized, controlled study. Dis. Colon Rectum 2008; 51: 494–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Vaizey CJ, Kamm MA, Roy AJ, Nicholls RJ. Double‐blind crossover study of sacral nerve stimulation for fecal incontinence. Dis. Colon Rectum 2000; 43: 298–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Abdel‐Halim MR, Crosbie J, Engledow A, Windsor A, Cohen CR, Emmanuel AV. Temporary sacral nerve stimulation alters rectal sensory function: a physiological study. Dis. Colon Rectum 2011; 54: 1134–1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Altomare DF, Ratto C, Ganio E, Lolli P, Masin A, Villani RD. Long‐term outcome of sacral nerve stimulation for fecal incontinence. Dis. Colon Rectum 2009; 52: 11–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chan MK, Tjandra JJ. Sacral nerve stimulation for fecal incontinence: external anal sphincter defect vs. intact anal sphincter. Dis. Colon Rectum 2008; 51: 1015–1024, discussion 1024‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ganio E, Ratto C, Masin A et al Neuromodulation for fecal incontinence: outcome in 16 patients with definitive implant. The initial Italian Sacral Neurostimulation Group (GINS) experience. Dis. Colon Rectum 2001; 44: 965–970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ganio E, Luc AR, Clerico G, Trompetto M. Sacral nerve stimulation for treatment of fecal incontinence: a novel approach for intractable fecal incontinence. Dis. Colon Rectum 2001; 44: 619–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ganio E, Masin A, Ratto C et al Short‐term sacral nerve stimulation for functional anorectal and urinary disturbances: results in 40 patients: evaluation of a new option for anorectal functional disorders. Dis. Colon Rectum 2001; 44: 1261–1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. El‐Gazzaz G, Zutshi M, Salcedo L, Hammel J, Rackley R, Hull T. Sacral neuromodulation for the treatment of fecal incontinence and urinary incontinence in female patients: long‐term follow‐up. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 2009; 24: 1377–1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hollingshead JR, Dudding TC, Vaizey CJ. Sacral nerve stimulation for faecal incontinence: results from a single centre over a 10‐year period. Colorectal Dis. 2011; 13: 1030–1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jarrett ME, Matzel KE, Christiansen J et al Sacral nerve stimulation for faecal incontinence in patients with previous partial spinal injury including disc prolapse. Br. J. Surg. 2005; 92: 734–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kenefick NJ, Vaizey CJ, Cohen CRG, Nicholls RJ, Kamm MA. Double‐blind placebo‐controlled crossover study of sacral nerve stimulation for idiopathic constipation. Br. J. Surg. 2002; 89: 1570–1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Leroi AM, Michot F, Grise P, Denis P. Effect of sacral nerve stimulation in patients with fecal and urinary incontinence. Dis. Colon Rectum 2001; 44: 779–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Matzel KE, Kamm MA, Stösser M et al Sacral spinal nerve stimulation for faecal incontinence: multicentre study. Lancet 2004; 363: 1270–1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Matzel KE, Stadelmaier U, Hohenfellner M, Hohenberger W. Chronic sacral spinal nerve stimulation for fecal incontinence. Dis. Colon Rectum 2001; 44: 59–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. McNevin S, Moore M, Bax T. Outcomes associated with Interstim therapy for medically refractory fecal incontinence. Am. J. Surg. 2014; 207: 735–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Melenhorst J, Koch SM, Uludag Ö, van Gemert WG, Baeten CG. Sacral neuromodulation in patients with faecal incontinence: results of the first 100 permanent implantations. Colorectal Dis. 2007; 9: 725–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Melenhorst J, Koch SM, Uludag Ö, van Gemert WG, Baeten CG. Is a morphologically intact anal sphincter necessary for success with sacral nerve modulation in patients with faecal incontinence? Colorectal Dis. 2008; 10: 257–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Otto SD, Burmeister S, Buhr HJ, Kroesen A. Sacral nerve stimulation induces changes in the pelvic floor and rectum that improve continence and quality of life. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2010; 14: 636–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Patton V, Wiklendt L, Arkwright JW, Lubowski DZ, Dinning PG. The effect of sacral nerve stimulation on distal colonic motility in patients with faecal incontinence. Br. J. Surg. 2013; 100: 959–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ratto C, Litta F, Parello A, Donisi L, Doglietto GB. Sacral nerve stimulation is a valid approach in fecal incontinence due to sphincter lesions when compared to sphincter repair. Dis. Colon Rectum 2010; 53: 264–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Roman S, Tatagiba T, Damon H, Barth X, Mion F. Sacral nerve stimulation and rectal function: results of a prospective study in faecal incontinence. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2008; 20: 1127–1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sheldon R, Kiff ES, Clarke A, Harris ML, Hamdy S. Sacral nerve stimulation reduces corticoanal excitability in patients with faecal incontinence. Br. J. Surg. 2005; 92: 1423–1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wong MT, Meurette G, Rodat F, Regenet N, Wyart V, Lehur PA. Outcome and management of patients in whom sacral nerve stimulation for fecal incontinence failed. Dis. Colon Rectum 2011; 54: 425–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Leroi A‐M, Parc Y, Lehur P‐A et al Efficacy of sacral nerve stimulation for fecal incontinence. Ann. Surg. 2005; 242: 662–669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Boyle DJ, Murphy J, Gooneratne ML et al Efficacy of sacral nerve stimulation for the treatment of fecal incontinence. Dis. Colon Rectum 2011; 54: 1271–1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Oz‐Duyos AM, Navarro‐Luna A, Brosa M, Pando JA, Sitges‐Serra A, Marco‐Molina C. Clinical and cost effectiveness of sacral nerve stimulation for faecal incontinence. Br. J. Surg. 2008; 95: 1037–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Jarrett ME, Matzel KE, Stösser M, Baeten CG, Kamm MA. Sacral nerve stimulation for fecal incontinence following surgery for rectal prolapse repair: a multicenter study. Dis. Colon Rectum 2005; 48: 1243–1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. George AT, Kalmar K, Panarese A, Dudding TC, Nicholls RJ, Vaizey CJ. Long‐term outcomes of sacral nerve stimulation for fecal incontinence. Dis. Colon Rectum 2012; 55: 302–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Santoro GA, Infantino A, Cancian L, Battistella G, Di Falco G. Sacral nerve stimulation for fecal incontinence related to external sphincter atrophy. Dis. Colon Rectum 2012; 55: 797–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kenefick NJ, Vaizey CJ, Cohen RC, Nicholls RJ, Kamm MA. Medium‐term results of permanent sacral nerve stimulation for faecal incontinence. Br. J. Surg. 2002; 89: 896–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kenefick NJ. Sacral nerve neuromodulation for the treatment of lower bowel motility disorders. Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 2006; 88: 617–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Vaizey CJ, Kamm MA, Turner IC, Nicholls RJ, Woloszko J. Effects of short term sacral nerve stimulation on anal and rectal function in patients with anal incontinence. Gut 1999; 44: 407–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Chan MK, Tjandra JJ. Sacral nerve stimulation for fecal incontinence: external anal sphincter defect vs. intact anal sphincter. Dis. Colon Rectum 2008; 51: 1015–1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ripetti V, Caputo D, Ausania F, Esposito E, Bruni R, Arullani A. Sacral nerve neuromodulation improves physical, psychological and social quality of life in patients with fecal incontinence. Tech. Coloproctol. 2002; 6: 147–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Michelsen HB, Buntzen S, Krogh K, Laurberg S. Rectal volume tolerability and anal pressures in patients with fecal incontinence treated with sacral nerve stimulation. Dis. Colon Rectum 2006; 49: 1039–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Uludag O, Morren GL, Dejong CH, Baeten CG. Effect of sacral neuromodulation on the rectum. Br. J. Surg. 2005; 92: 1017–1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Michelsen HB, Maeda Y, Lundby L, Krogh K, Buntzen S, Laurberg S. Retention test in sacral nerve stimulation for fecal incontinence. Dis. Colon Rectum 2009; 52: 1864–1868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Michelsen HB, Worsøe J, Krogh K et al Rectal motility after sacral nerve stimulation for faecal incontinence. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2010; 22: 36–41, e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Worsøe J, Fassov J, Schlageter V, Rijkhoff NJ, Laurberg S, Krogh K. Turning off sacral nerve stimulation does not affect gastric and small intestinal motility in patients treated for faecal incontinence. Colorectal Dis. 2012; 14: e713–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Damgaard M, Thomsen FG, Sørensen M, Fuglsang S, Madsen JL. The influence of sacral nerve stimulation on gastrointestinal motor function in patients with fecal incontinence. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2011; 23: 556–e207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Michelsen HB, Christensen P, Krogh K et al Sacral nerve stimulation for faecal incontinence alters colorectal transport. Br. J. Surg. 2008; 95: 779–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Uludag O, Koch SM, Dejong CH, Gemert WG, Baeten CG. Sacral neuromodulation; does it affect colonic transit time in patients with faecal incontinence? Colorectal Dis. 2006; 8: 318–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Gourcerol G, Gallas S, Michot F, Denis P, Leroi A‐M. Sacral nerve stimulation in fecal incontinence: are there factors associated with success? Dis. Colon Rectum 2007; 50: 3–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Maeda Y, Lundby L, Buntzen S, Laurberg S. Outcome of sacral nerve stimulation for fecal incontinence at 5 years. Ann. Surg. 2014; 259: 1126–1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Dudding TC, Parés D, Vaizey CJ, Kamm MA. Predictive factors for successful sacral nerve stimulation in the treatment of faecal incontinence: a 10‐year cohort analysis. Colorectal Dis. 2008; 10: 249–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Govaert B, Melenhorst J, Nieman FH, Bols EM, van Gemert WG, Baeten CG. Factors associated with percutaneous nerve evaluation and permanent sacral nerve modulation outcome in patients with fecal incontinence. Dis. Colon Rectum 2009; 52: 1688–1694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Murphy J, Chan CL, Scott SM, Vasudevan SP, Lunniss PJ, Williams NS. Rectal augmentation: short‐ and mid‐term evaluation of a novel procedure for severe fecal urgency with associated incontinence. Ann. Surg. 2008; 247: 421–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Chan CL, Lunniss PJ, Wang D, Williams NS, Scott SM. Rectal sensorimotor dysfunction in patients with urge faecal incontinence: evidence from prolonged manometric studies. Gut 2005; 54: 1263–1272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Gladman MA, Scott SM, Chan CL, Williams NS, Lunniss PJ. Rectal hyposensitivity: prevalence and clinical impact in patients with intractable constipation and fecal incontinence. Dis. Colon Rectum 2003; 46: 238–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Burgell RE, Bhan C, Lunniss PJ, Scott SM. Fecal incontinence in men: coexistent constipation and impact of rectal hyposensitivity. Dis. Colon Rectum 2012; 55: 18–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Knowles CH, Thin N, Gill K et al Prospective randomized double‐blind study of temporary sacral nerve stimulation in patients with rectal evacuatory dysfunction and rectal hyposensitivity. Ann. Surg. 2012; 255: 643–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Gladman MA, Dvorkin LS, Lunniss PJ, Williams NS, Scott SM. Rectal hyposensitivity: a disorder of the rectal wall or the afferent pathway? An assessment using the barostat. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2005; 100: 106–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Roy A‐L, Gourcerol G, Menard J‐F, Michot F, Leroi A‐M, Bridoux V. Predictive factors for successful sacral nerve stimulation in the treatment of fecal incontinence. Dis. Colon Rectum 2014; 57: 772–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Oom DMJ, Steensma AB, van Lanschot JJB, Schouten WR. Is sacral neuromodulation for fecal incontinence worthwhile in patients with associated pelvic floor injury? Dis. Colon Rectum 2010; 53: 422–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1 Impact of sacral neuromodulation on clinical outcomes (median values).

Table S2 Impact of sacral neuromodulation on anorectal physiology (median values).

Table S3 Significant factors associated with sacral neuromodulation clinical outcome.