Abstract

Pure iron has been demonstrated as a potential candidate for biodegradable metal stents due to its appropriate biocompatibility, suitable mechanical properties and uniform biodegradation behavior. The competing parameters that control the safety and the performance of BMS include proper strength-ductility combination, biocompatibility along with matching rate of corrosion with healing rate of arteries. Being a micrometre-scale biomedical device, the mentioned variables have been found to be governed by the average grain size of the bulk material. Thermo-mechanical processing techniques of the cold rolling and annealing were used to grain-refine the pure iron. Pure Fe samples were unidirectionally cold rolled and then isochronally annealed at different temperatures with the intention of inducing different ranges of grain size. The effect of thermo-mechanical treatment on mechanical properties and corrosion rates of the samples were investigated, correspondingly. Mechanical properties of pure Fe samples improved significantly with decrease in grain size while the corrosion rate decreased marginally with decrease in the average grain sizes. These findings could lead to the optimization of the properties to attain an adequate biodegradation-strength-ductility balance.

KEYWORDS: annealing, biodegradable metal, cold rolling, corrosion rate, iron stent, mechanical properties

Introduction

Iron-based biodegradable metal stents (BMS) has been presented as a potential interventional cardiovascular implant for temporary blood vessel scaffolding after balloon angioplasty. Since the pioneering work of Peuster et al. on introducing high purity iron (Fe) as biodegradable stent material, investigations revealed that pure Fe has a suitable mechanical properties as well as a slow and uniform biodegradation behavior.1,2

BMS requires appropriate strength-ductility combination, in addition ensured biocompatibility and corrosion rate matching the tissue healing rate.3 It needs sufficient strength to preserve its load-bearing function and adequate ductility for a safe deployment during implantation. Moreover, biodegradable stents need requisite fatigue strength as they have to withstand many millions of alternating pressure loadings due to the blood pressure.4 Average grain size is the key microstructural parameter that affects all aspects of the physical and mechanical behavior of polycrystalline metals, including their chemical and biochemical response to the surrounding media.5 In general, mechanical properties of polycrystalline metals especially ferrous materials increase with decrease in the average grain size according to Hall-Petch relationship (Eq. 1):

| (1) |

where σy is yield strength, σi is friction stress, Ky is Hall-Petch slope and d is the grain size.6 Although a decrease in grain size generally leads to a decrease in ductility of single phase metals,7 but the ductility of micron-scale stent strut has been found to be sensitive to microstructure and could be optimized by the average grain size.8 Currently, metallic stent with strut thickness in the range of 50–140 μm are required to be made with smaller range of grain size and to be more miniature for both mechanical and clinical approach.8,9 The reduced thickness of the struts has been reported to increase the stent flexibility, reduce the cross-sectional profiles and decrease the pressure needed for deployment.10,11 Thinner struts reduce the rate of restenosis significantly and are associated with faster re-endothelialization when compared to thicker struts.12,13

There is a current trend in the corrosion community to adjust and control the degradation behavior of metals through grain refinement techniques. These techniques are great approaches for controlling the corrosion rate of biometals without changing chemistry of the base alloy. Researchers in biodegradable metals domain are confronted by limited number of non-toxic elements that can be alloyed with base metals of Fe and Mg to form medical grade alloys. Controlled corrosion rate is crucial to BMS as it influences the loss of mechanical integrity and release of corroded products during in vivo biodegradation, accordingly affects the biocompatibility or tolerance limit of these products by the surrounding tissues.14 Moreover, fine-grained metals have been found to exhibit better host-implant interactions and lessen the inflammatory response.15

A relationship between the average grain size and corrosion rate of a material, similar to the Hall-Petch relation, has been proposed by Ralston and Birbilis.16 The proposed relationship (Eq. 2) is as follows:

| (2) |

where icorr is corrosion current, A and B are constants whose values depend on the material (composition or impurity level) and on the nature of the media, respectively, and d is the average grain size. The above relationship implies that whether variation in average grain size of material leads to enhance its dissolution or passivation is dependent on a synergy between material, its processing background and its surrounding media. B assumes a positive value in a non-passivating environment leading to increase in corrosion rate as grain size decreases in the absence of oxide film and a negative value in a passivating environment resulting in decrease in corrosion rate as grain size decreases in the presence of oxide film. Alternative relationship between corrosion current and grain size distribution has been proposed by Gollapudi.17 The relation (Eq. 3) is as follows:

| (3) |

where icorr is corrosion current, A and B are the same as in previous equation, is the mean grain size and Sn is the grain size distribution. This relation implies that as the grain size distribution increases or becomes broader, the corrosion rate of a metal could decreases in a non-passivating environment while it could increases in a passivating environment and vice versa.

Grain refinement and material processing are interwoven as microstructural parameters; grain size, grain shape, texture or preferred crystallographic orientation inherently change with processing conditions.18 There is no general consensus in the literature as to the effect of the average grain size on corrosion of differently-processed pure iron in various media. Only very few researchers have investigated specifically the effect of average grain size on the biodegradation behavior of pure Fe in simulated body fluids (SBF). Fine grain pure iron (∼4 μm) produced by electrodeposition was shown to have an effect on corrosion rate enhancement in Hanks’ solution.19 Whereas, Nie et al.20 reported that pure iron rods (>99.8 wt. %), grain-refined by equal channel angular pressure (ECAP) technique, revealed more corrosion resistance in the nanosize range (80–200 nm) than in microsize range (∼50 μm) when contacting with Hanks’ solution.

Taking into account the unfolding effect of the average grain size on biodegradation behavior and its well-known effect on mechanical properties of stent materials, this work aimed at exploring the extent of dependence of these properties on the average grain size.

Results and discussion

Chemical composition, microstructure and grain size measurement

The chemical composition of impurity elements in the as-received Armco pure iron is shown in Table 1. Segregation of the non-metallic impurities, carbon and sulfur, to grain boundaries in iron-based materials might affect material properties such as the corrosion resistance or the mechanical strength of iron-based alloys.

Table 1.

Concentration of impurity elements in the as-received Armco iron.

| Element | C | Ni | Cr | Mn | Cu | Mo | S | Sn | P | Si | Al |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight % | 0.006 | 0.037 | 0.032 | 0.041 | 0.017 | 0.002 | 0.014 | 0.014 | 0.019 | 0.008 | 0.010 |

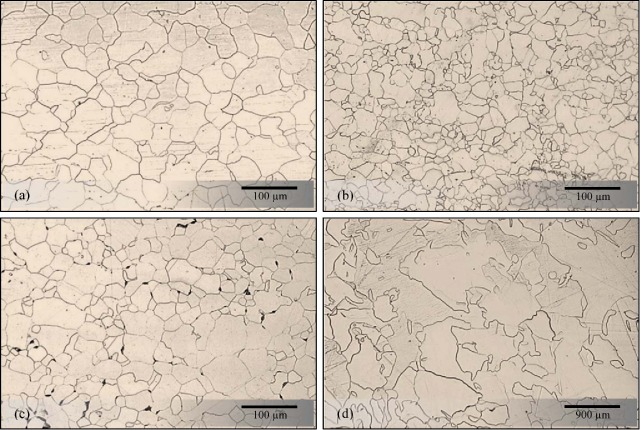

Optical microscopy of all Fe samples, as-received and treated, revealed fully equiaxed ferritic microstructures (Fig. 1). The average grain size of as-received samples was measured approximately 29.6 ± 4 μm, as shown in Fig 1a The UD cold-rolled samples were annealed in a tube furnace in temperature range of 550°C to 1000°C. Three groups of samples with different ranges of average grain size are selected, as shown in Fig 1.

Figure 1.

OM images of pure iron: (a) as-received, (b) 85% cold rolled, annealed at 550°C, (c) 75% cold rolled, annealed at 800°C and (d) 85% cold rolled, annealed at 1000°C.

Mechanical properties

The tensile properties of the annealed samples were compared with the as-received one, as shown in Table 2. The 85%UR-550 has the smallest average grain size and the highest strength. 21 The yield and tensile strengths of 75%UR-800 and 85%UR-1000 are lower than that of the as-received pure iron. It could be attributed to this fact that annealing declines amount of dislocation density, relieves residual stresses, softens the metals and restores ductility.22 It changes the average grain size which has a significant effect on mechanical properties, yield and tensile strengths, of the samples. The 85%UR-1000 has largest average grain size but has both the lowest tensile strength and elongation at break.

Table 2.

Average grain size and mechanical properties of the as-received and annealed pure iron samples.

| Material | Average grain size (μm) | Yield Strength (MPa) | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Elongation at break (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| As-received | 29.6 ± 4.0 | 170 ± 2 | 270 ± 5 | 49.3 ± 3.5 |

| 85%UR-550 | 14.1 ± 1.3 | 236 ± 13 | 287 ± 7 | 46.1 ± 4.2 |

| 75%UR-800 | 28.1 ± 2.9 | 104 ± 2 | 238 ± 5 | 47.0 ± 4.1 |

| 85%UR-1000 | 168.0 ± 28 | 93 ± 9 | 173 ± 17 | 17.2 ± 6.4 |

It was validated that by a combination of different degree of cold working and annealing temperature it is possible to impact significantly final mechanical properties of sample. Formability and strength properties of the studied samples fall with increase in annealing temperature due to the abnormal grain growth. Larger average grain sizes are detrimental to the desired strength, ductility and other beneficial grain-dependent properties of BMS.

Biodegradation behavior

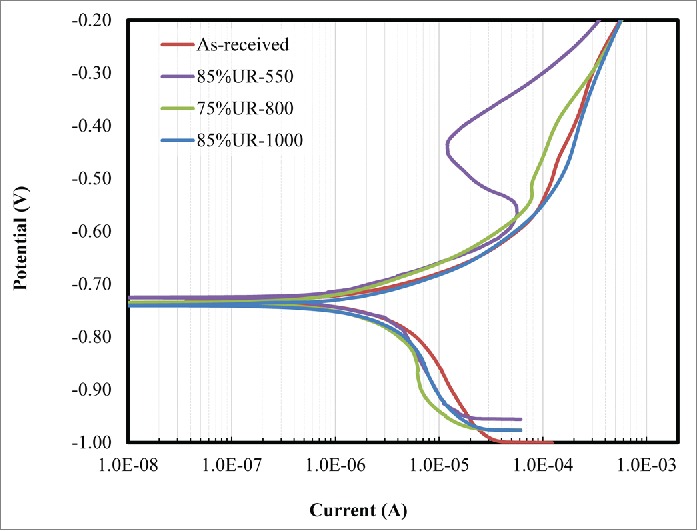

The average corrosion rates of as-received and treated samples based on weight loss method as determined by equation (4) are shown in Table 3. There were only minor differences in the average corrosion rates of the as-received and annealed Fe samples from the weight loss examination. The corresponding potentiodynamic polarization curves of selected samples are presented in Fig. 2; while corrosion rates calculated from Eq. (5) using the current densities deduced from the curves are shown in Table 3. Similar minor differences in corrosion rates were observed in the potentiodynamic polarization test. Noteworthy, the slight differences in corrosion rates of the annealed Fe samples are grain-size dependent in both static and potentiodynamic polarization tests.

Table 3.

Average corrosion rates based on weight loss method, corrosion current densities and potentials of the as-received and annealed pure iron samples obtained via the potentiodynamic polarization curves and resulting calculated corrosion rates.

| Material | Icorr(μA.cm−2) | Potential (mV) | Corrosion rate (mm.yr−1) | Average corrosion rate (mm.yr−1) | Average grain size (μm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| As-received | 20.89 ± 0.62 | −732 ± 3 | 0.242 ± 0.013 | 0.138 ± 0.011 | 29.6 ± 4.0 |

| 85%UR-550 | 14.88 ± 0.92 | −724 ± 4 | 0.172 ± 0.012 | 0.120 ± 0.006 | 14.1 ± 1.3 |

| 75%UR-800 | 18.50 ± 0.70 | −735 ± 11 | 0.215 ± 0.043 | 0.127 ± 0.003 | 28.1 ± 2.9 |

| 85%UR-1000 | 21.05 ±2.63 | −740 ± 8 | 0.244 ± 0.031 | 0.146 ± 0.007 | 168.0 ± 28 |

Figure 2.

Potentiodynamic polarization curves for the as-received pure iron and annealed samples.

According to the results, the corrosion rates of samples in Hanks’ solution reduced slightly with decrease in the average grain size. This in agreement with proposal made by Ralston and Birbilis16 that in a passivating environment, corrosion rate of a pure metal decreases as grain size decreases. Small grain sizes are accompanied by high volume of grain boundaries and are expected to be more active in a corrosive medium than coarse grains with less volume of grain boundaries. It has been shown that small grains have higher volume of grain boundaries, which lead to enhanced chemical activities in corroding media. However, whether the increased activities would lead to increase in dissolution rate depends on the environment (pH) and the nature of the metal.18 In a passivating environment (pH > 7.0), the increased activities at the grain boundaries on small-grained and oxide film forming metal, will enable the formation of more compact and stable passive films or oxides on the corroding surface.18 The compact oxide films impede further dissolution of the metal. This result is in agreement with other findings that corrosion rate of extreme grain-refined pure Fe decreases as grain size decreases in SBF20 and other passive media.23,24 The corrosion rates of the Fe samples also decreased as the grain size distributions become narrower in passivating environments, as proposed by Gollapudi.17 The 85%UR-1000 has the highest GSD of 28.0 μm and highest corrosion rate, followed by the as-received, 75%UR-800 and 85%UR-550 with grain size distribution of 4.0, 2.9 and 1.3 microns, respectively.

The 85%UR-550 has the smallest average grain size, noblest potential, lowest corrosion current density and lowest corrosion rate among the samples. It also exhibited the deepest passivation, showing that the extent of passivation of pure Fe is grain size-dependent. This is in agreement with the finding that the nucleation and growth of oxide films on metals exhibit some level of passivity scale with grain size.16 Therefore, the low degradation rate of 85%UR-550 could be attributed to growth and deposition of passivating oxide films of Fe2O3, Fe3(PO4)2, Ca3(PO4)2 and Mg3(PO4)2 from Hanks’ solution on the corroded Fe surface, thereby impeding the process of anodic dissolution.25,26

The potentiodynamic polarization curves equally demonstrate that the as-received, 75%UR-800 and 85%UR-1000 samples have similar corrosion behavior showing small passivation in anodic region of the Tafel plot, but the passivity was unstable and discontinuous in present of chloride, sulfate and phosphate ions. Smaller grain size promotes the formation of a dense passive film; the degree of protectiveness and stability of oxide films increase as the grain size decreases and also depend on other factors such as texture, residual stress and environment.16,27 Breakdown of the oxide films could lead to enhanced corrosion rate and might be responsible for the slightly enhanced corrosion rate of pure Fe samples annealed at higher temperatures. It has been reported that inhibitors are adsorbed more strongly from acidic and alkaline solutions on Fe surface subjected to cold mechanical treatment (with or without subsequent annealing at ≤600°C) than on identical specimens annealed at ≥750°C.28 It follows that pure Fe annealed at higher temperatures would be less corrosion resistant due to reduced adsorption of passive oxides from Hanks’ solution. The slight increase in the corrosion rate of 85%UR-1000 could also be attributed to carbide precipitation along the grain boundaries, thereby forming active galvanic cells and increasing anodic dissolution.29 Although, 85%UR-1000 has the highest corrosion rate, this increase is offset by its big grain size and low mechanical properties.

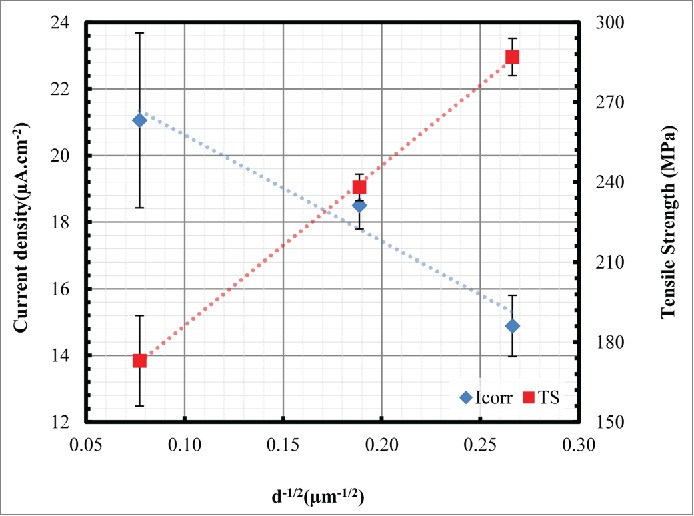

Grain size: evidence for optimization of strength and biodegradation behavior

These results, as summarised in Fig. 3, appear to closely follow the Hall–Petch relationship in the case of tensile strengthening versus decreasing recrystallized grain size,21 and to follow the Ralston et al.16 relationship in the case of decreasing corrosion current densities vs decreasing recrystallized grain size. The optimum microstructure for thermo-mechanical treated pure iron, which exhibits average grain size of ∼20 μm, combines the strengthening from the reduced grain size along with the good biodegradation behavior provided by fewer grain boundaries. At the smaller grain size (∼14 μm), the strain hardening is improving the mechanical properties. While increasing the grain size, e.g. up to ∼168 μm, the corrosion rate increases due to less grain boundary volume and accordingly less dense passive layer.

Figure 3.

The relationship between corrosion rate and mechanical properties with average grain sizes for polycrystalline pure iron (R2 > 0.9).

Materials and methods

Cold rolling and annealing treatments

The material in the form of as-rolled sheet of Armco® soft ingot iron with purity of >99.8% was supplied by Goodfellow Limited, Cambridge, United Kingdom. Samples were cut from the 2 mm-thick pure iron sheets which were then cold rolled to thickness reduction of 75% (75%UR) and 85% (85%UR) to achieve 0.5 mm and 0.3 mm thickness, respectively. Rolling was unidirectional with reduction in thickness limited to 0.2 mm per pass at a rolling speed of 32 r.p.m on a 2-high rolling mill, using 130 mm diameter work rolls (Stanat, Rolling Mill, Model TA-315). In order to induce different ranges of grain size, the UD cold-rolled samples were annealed in a tube furnace in temperature range of 550°C to 1000°C, under a high purity argon atmosphere with a heating rate of 6.5°C.min−1 soaked for one hour and furnace cooled afterwards.

Chemical composition, microstructure and grain size measurements

The bulk chemical composition of the Armco pure iron was determined by LECO carbon-sulfur analyzer and atomic absorption spectrophotometer. The microstructure and grain size of the as-received and treated pure iron samples were observed on the rolled surface and determined using optical microscope (Nikon Epiphot 200, Japan) equipped with Clemex Vision image analyzer (Clemex, Longueuil, Canada). Prior to microstructural examination and grain size measurement, samples were mounted in acrylic resin and were polished to a 0.5 μm surface finish. They were then etched using a 2% Nital (2 vol. % nitric acid in ethanol) to delineate grain boundaries.

Mechanical properties

Subsize dog-bone-shaped tensile specimens having a gauge length of 25 mm, width of 6.38 mm, total length of 100 mm were machined along the rolling direction following ASTM E8 standard.30 The thickness of the as-received Fe was 2 mm whereas the treated samples had thickness of 0.5 and 0.3 mm. Tensile tests were carried out at room temperature using computer-controlled universal testing machine (SATEC T2000, USA) at a strain rate of 0.033 mm.s−1. The mechanical tests were done to ascertain the effect of grain size variation on mechanical properties. Five specimens were tested in each case.

Biodegradation behavior studies

Two different kinds of degradation test, static immersion and potentiodynamic polarization tests were used to assess the biodegradation behavior of the iron samples in a modified Hanks’ solution having ionic composition and concentration close to that of human blood plasma. The test solution was prepared by dissolving Hanks’ modified salt (H1387, Sigma Aldrich, USA) in deionized water, with the addition of HEPES acid (H3375, Sigma Aldrich, Canada); sodium bicarbonate (SX0320-1, Merck KGaA, Germany) and HEPES sodium salt (DB0265, Bio Basic, Canada) as buffers to adjust the pH of the solution to 7.4, the pH of human blood plasma. The composition of Hanks’ solution was presented in Ref. (31). The static immersion and potentiodynamic polarization tests were performed following ASTM G3132 and G5933 standards, respectively.

Static immersion test

The samples for static degradation test with sizes 20 × 10 × 2 mm3, 20 × 10 × 0.5 mm3 and 20 × 10 × 0.3 mm3 for the as-received, 75%UR and 85%UR respectively, were cut and polished with SiC papers up to 4000 grit, and then cleaned with ethanol, dried and weighted. Each specimen was suspended in 80 mL-beaker of modified Hanks’ solution separately and incubated in a thermostatic water bath at a temperature of 37 ± 1°C for 336 hours (14 days).

At the end of the test period, the degraded layers of the samples were removed by rinsing with distilled water and ethanol. The average corrosion rate (ACR) was determined based on the weight loss using Eq. (4) from ASTM G31 standard.32

| (4) |

where ACR is the average corrosion rate in millimeter per year (mm.yr−1), W is the weight loss in grams (g), A is the exposed surface area (cm2), t is the time of exposure in hours, and ρ is the density (7.87 g.cm−3 for Fe ).

Potentiodynamic polarization test

The potentiodynamic polarization test was performed using a 3-electrode cell, in which a saturated calomel electrode (SCE) was used as a reference electrode, a graphite electrode as a counter electrode and the sample as the working electrode. The 3-electrode measurement system was a VersaSTAT3 potentiostat/galvanostat system (Princeton Applied Research, USA). Each corrosion test was performed in 650 ml of Hanks’ solution having a pH of 7.4. The solution was stirred and temperature maintained at 37 ± 1°C during the corrosion tests. Disc shaped specimens having a total surface area of 1.30 cm2 were cut, and polished with SiC papers up to 4000 grit, and then cleaned with ethanol and dried. However, during the test, only 0.16 cm2 of the total surface area was exposed to the electrolyte. The Potentiodynamic polarization test was carried out at an applied potential in the range of −1000 mV to −250 mV at a scanning rate of 0.166 mV.s−1. Prior to each corrosion test, the working electrode was allowed to stabilize in the Hanks’ solution for 1 hr. The corrosion rate was calculated using Eq. (5) based on ASTM G59.33

| (5) |

Where CR is the corrosion rate (mm.yr−1), icorr is the corrosion current density (μA.cm−2) deduced from Tafel curves, EW is the equivalent weight (27.92 g.eq−1 for Fe) and ρ is the density.

Conclusion

The results revealed the tensile strength, ultimate strength and ductility of pure iron samples were grain-size dependent, increasing with decreasing recrystallized grain size according to the Hall-Petch relationship. The result also demonstrates that annealing of pure iron sample at higher temperatures accompanied by slow cooling leads to abnormal grain growth. Larger grain sizes are detrimental to the desired strength, ductility and other beneficial grain size-dependent properties of BMS.

The corrosion rates of the cold rolled and annealed pure Fe samples decreased slightly with decrease in grain sizes and decrease in grain size distribution in both static immersion and potentiodynamic polarization tests. The pure Fe sample having the smallest average grain size and narrower grain size distribution exhibited lowest corrosion rate and deepest passivation while the sample having the largest average grain size and broader grain size distribution had the highest corrosion rate. The advantage of having the highest corrosion rate by the biggest grained Fe sample annealed at a higher temperature is offset by its low mechanical properties.

The interesting outcome of this work is that it opens a new direction to optimize the mechanical properties and corrosion rates of pure Fe as a candidate BMS material by grain refinement. Since mechanical properties increase and corrosion rate decreases with decrease in average grain size, strength, ductility and biodegradation rate can be optimized. In this work the optimum microstructure for thermo-mechanical treated samples is reached with the average grain size of ∼20–25 μm.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed

Acknowledgments

We are equally grateful to Andre Ferland, Marc Choquette, Maude Larouche, Vicky Dodier, Jean Frenette and Daniel Marcotte, from the Department of Mining, Metallurgical and Materials Engineering, Laval University, Quebec City, Canada, for assistance and technical support.

Funding

We wish to thank the Canadian Commonwealth Scholarship Program for scholarship award to C.S.O. for a PhD training at Laval University. We are also grateful to University of Nigeria, Nsukka, for sponsoring another six months research stay in the above lab. This research was partially funded by the Natural Science and Engineering Research Council of Canada, the Canadian Institute for Health Research and the CHU de Quebec Research Center.

References

- 1. Peuster M, Wohlsein P, Brügmann M, Ehlerding M, Seidler K, Fink C, Brauer H, Fischer A, Hausdorf G. A novel approach to temporary stenting: degradable cardiovascular stents produced from corrodible metal—results 6–18 months after implantation into New Zealand white rabbits. Heart 2001; 86:563-9; PMID:11602554; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1136/heart.86.5.563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Peuster M, Hesse C, Schloo T, Fink C, Beerbaum P, von Schnakenburg C. Long-term biocompatibility of a corrodible peripheral iron stent in the porcine descending aorta. Biomaterials 2006; 27:4955-62; PMID:16765434; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.05.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hermawan H, Mantovani D. New generation of medical implants: metallic biodegradable coronary stent. Instrumentation, Communications, Inform Technol Biomed Eng (ICICI-BME), 2011 2nd Inter Conf. IEEE, 2011:399-402. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Möller D, Reimers W, Pyzalla A, Fischer A. Residual stresses in coronary artery stents. J Biomed Mater Res 2001; 58:69-74; PMID:11153000; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/1097-4636(2001)58:1<69::AID-JBM100>3.0.CO;2-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Estrin Y, Vinogradov A. Extreme grain refinement by severe plastic deformation: A wealth of challenging science. Acta Mater 2013; 61:782-817; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.actamat.2012.10.038 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kashyap B, Tangri K. On the Hall-Petch relationship and substructural evolution in type 316L stainless steel. Acta Metall Mater 1995; 43:3971-81; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/0956-7151(95)00110-H [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Song R, Ponge D, Raabe D, Speer J, Matlock D. Overview of processing, microstructure and mechanical properties of ultrafine grained bcc steels. Mater Sci Eng: A 2006; 441:1-7; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.msea.2006.08.095 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Murphy B, Cuddy H, Harewood F, Connolley T, McHugh P. The influence of grain size on the ductility of micro-scale stainless steel stent struts. J Mater Sci: Mater Med 2006; 17:1-6; PMID:16389466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ürgen Pache J, Kastrati A, Mehilli J, Schühlen H, Dotzer F, örg Hausleiter J, Fleckenstein M, Neumann F-J, Sattelberger U, Schmitt C. Intracoronary stenting and angiographic results: strut thickness effect on restenosis outcome (ISAR-STEREO-2) trial. J Am College of Cardiol 2003; 41:1283-8; PMID:12706922; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0735-1097(03)00119-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. O’Brien B, Carroll W. The evolution of cardiovascular stent materials and surfaces in response to clinical drivers: a review. Acta Biomater 2009; 5:945-58; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.actbio.2008.11.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kathuria Y. The potential of biocompatible metallic stents and preventing restenosis. Mater Sci Eng: A 2006; 417:40-8; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.msea.2005.11.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. `Rittersma SZ, de Winter RJ, Koch KT, Bax M, Schotborgh CE, Mulder KJ, Tijssen JG, Piek JJ. Impact of strut thickness on late luminal loss after coronary artery stent placement. Am J Cardiol 2004; 93:477-80; PMID:14969629; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.amjcard.2003.10.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kitabata H, Kubo T, Komukai K, Ishibashi K, Tanimoto T, Ino Y, Takarada S, Ozaki Y, Kashiwagi M, Orii M. Effect of strut thickness on neointimal atherosclerotic change over an extended follow-up period (≥4 years) after bare-metal stent implantation: Intracoronary optical coherence tomography examination. Am Heart J 2012; 163:608-16; PMID:22520527; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ahj.2012.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sing N, Mostavan A, Hamzah E, Mantovani D, Hermawan H. Degradation behavior of biodegradable Fe35Mn alloy stents. J Biomed Mater Res Part B: Appl Biomater 2014; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/jbm.b.33242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Misra R, Nune C, Pesacreta T, Somani M, Karjalainen L. Understanding the Impact of Grain Structure in Austenitic Stainless Steel from Nano-Grained Regime to Coarse-Grained Regime on Osteoblast Functions using a Novel Metal Deformation-Annealing Sequence. Acta Biomater 2013; 9(4):6245-58; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.actbio.2012.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ralston K, Birbilis N, Davies C. Revealing the relationship between grain size and corrosion rate of metals. Scripta Mater 2010; 63:1201-4; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.scriptamat.2010.08.035 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gollapudi S. Grain size distribution effects on the corrosion behaviour of materials. Corros Sci 2012; 62:90-4; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.corsci.2012.04.040 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ralston K, Birbilis N. Effect of grain size on corrosion: a review. Corrosion 2010; 66:075005-13; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.5006/1.3462912 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Moravej M, Amira S, Prima F, Rahem A, Fiset M, Mantovani D. Effect of electrodeposition current density on the microstructure and the degradation of electroformed iron for degradable stents. Mater Sci Eng: B 2011; 176:1812-22; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.mseb.2011.02.031 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nie F, Zheng Y, Wei S, Hu C, Yang G. In vitro corrosion, cytotoxicity and hemocompatibility of bulk nanocrystalline pure iron. Biomed Mater 2010; 5:065015; PMID:21079282; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1088/1748-6041/5/6/065015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hansen N. Hall–Petch relation and boundary strengthening. Scripta Mater 2004; 51:801-6; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.scriptamat.2004.06.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Oyarzábal M, Martínez-de-Guerenu A, Gutiérrez I. Effect of stored energy and recovery on the overall recrystallization kinetics of a cold rolled low carbon steel. Mater Sci Eng: A 2008; 485:200-9; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.msea.2007.07.077 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Afshari V, Dehghanian C. Effects of grain size on the electrochemical corrosion behaviour of electrodeposited nanocrystalline Fe coatings in alkaline solution. Corros Sci 2009; 51:1844-9; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.corsci.2009.05.015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wang S, Shen C, Long K, Zhang T, Wang F, Zhang Z. The electrochemical corrosion of bulk nanocrystalline ingot Iron in acidic sulfate solution. J Phys Chem B 2006; 110:377-82; PMID:16471545; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1021/jp0538971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhang E, Chen H, Shen F. Biocorrosion properties and blood and cell compatibility of pure iron as a biodegradable biomaterial. J Mater Sci: Mater Med 2010; 21:2151-63; PMID:20396936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Afshari V, Dehghanian C. The influence of nanocrystalline state of iron on the corrosion inhibitor behavior in aqueous solution. J Appl Electrochem 2010; 40:1949-56; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s10800-010-0171-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Li HB, Jiang ZH, Li Z, Ma QF. Influence of Cold Working and Grain Size on Pitting Corrosion Resistance of Ferritic Stainless Steel. Adv Mater Res 2011; 217:1180-4. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Iofa Z, Batrakov V, Nikiforova YA. On the influence of deformation and heat treatment of Fe on adsorption and action of corrosion inhibitors. Corros Sci 1968; 8:573-82; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/S0010-938X(68)80093-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. El Din AS, El Kader JA, El Wahab FA, Hegazy H. Effect of cold work on anodic polarization of low carbon steel. J Mater sci 1983; 18:2732-42; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/BF00547590 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. ASTM Standard Test Methods for Tension Testing of Metallic Materials. West Conshohocken, PA: ASTM; 2013; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1520/E0008_E0008M [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lévesque J, Hermawan H, Dubé D, Mantovani D. Design of a pseudo-physiological test bench specific to the development of biodegradable metallic biomaterials. Acta Biomater 2008; 4:284-95; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1016/j.actbio.2007.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. ASTM Standard Guide for Laboratory Immersion Corrosion Testing of Metals. West Conshohocken, PA: ASTM; 2012; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1520/G0031-12A [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. ASTM Standard Test Method for Conducting Potentiodynamic Polarization Resistance Measurements. West Conshohocken, PA: ASTM; 2009; http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1520/G0059-97R09 [DOI] [Google Scholar]