Abstract

Background

Understanding the important factors for choosing a general practitioner (GP) can inform the provision of consumer information and contribute to the design of primary care services.

Objective

To identify the factors considered important when choosing a GP and to explore subgroup differences.

Design

An online survey asked about the respondent's experience of GP care and included 36 questions on characteristics important to the choice of GP.

Participants

An Australian population sample (n = 2481) of adults aged 16 or more.

Methods

Principal components analysis identified dimensions for the creation of summated scales, and regression analysis was used to identify patient characteristics associated with each scale.

Results

The 36 questions were combined into five scales (score range 1–5) labelled: care quality, types of services, availability, cost and practice characteristics. Care quality was the most important factor (mean = 4.4, SD = 0.6) which included questions about technical care, interpersonal care and continuity. Cost (including financial and time cost) was also important (mean = 4.1, SD = 0.6). The least important factor was types of services (mean = 3.3, SD = 0.9), which covered the range of different services provided by or co‐located with the practice. Frequent GP users and females had higher scores across all 5 scales, while the importance of care quality increased with age.

Conclusions

When choosing a GP, information about the quality of care would be most useful to consumers. Respondents varied in the importance given to some factors including types of services, suggesting the need for a range of alternative primary care services.

Keywords: consumers, general practice, preferences

Introduction

Understanding the factors consumers regard as important when choosing a general practitioner (GP) or primary health‐care provider can be important for ensuring the availability of relevant and useable information for consumer decision making. Identification of the practitioner and practice attributes regarded as important can also inform health‐care policy by contributing to the design of primary care services which reflect the priorities of the users of those services. This study aimed to identify the factors people in Australia consider important when choosing a GP and to examine the extent to which this varies by health and demographic characteristics.

Through an examination of conceptual reviews and empirical studies, Cheraghi‐Sohi1 developed a ‘conceptual map’ of the key attributes of primary care that were important to patients. They identified seven attribute categories: access (to care and to preferred services), technical care quality, interpersonal care (including communication and explanation), patient‐centredness, continuity (of information, care and provider), outcomes (including health status, quality of life and satisfaction) and hotel aspects (such as waiting room).1 This wide‐ranging list was found to be too large to be comprehensively addressed by most patient assessment instruments.

A number of survey methods have been used for measuring preferences in relation to primary care including direct rating of the importance of a range of attributes of care and discrete choice experiments (DCE). Direct questions rating the extent of preference for each attribute allow for the inclusion of a large number of different attributes but do not force respondents to weigh up the relative importance of different attributes and so may lack sensitivity to differences between attributes, for example where many respondents identify all or most attributes as important. Discrete choice experiments offer respondents a series of choices where attribute levels vary between choice options and across choices. This approach has the advantage of being able to quantify the extent to which respondents would trade attributes of care against each other but is constrained by the number of different attributes that can be feasibly considered at one time.

Discrete choice experiment surveys investigating preferences for GP services have originated mainly in Europe (predominantly the UK) and have generally found technical quality of care,2, 3 doctor communication,4, 5, 6, 7 information provided,4, 6, 8 continuity of care2, 3, 9, 10 and choice of provider9, 10, 11, 12, 13 to be the most important attributes for GP care among those included in the relevant experiments. In the Australian context, Haas14 found that trust in the doctor was more important than other interpersonal aspects for choosing to remain with a GP. In many of the DCE studies, respondents were willing to trade off speed of access for a GP appointment with the preferred attributes. Not surprisingly, preferences varied according to respondent characteristics such as age, gender and health status.

Results from studies using direct questions about the respondent's preference or strength of preference for individual attributes of care have varied somewhat according to the question and attributes included. Razzouk et al.15 asked respondents to rate the usefulness of 22 different information items (including patient satisfaction ratings) for choosing a new primary care physician. They found that respondents most frequently identified ratings of patient satisfaction with care quality, access and interpersonal skills as useful information for choosing a physician. Fung et al.16 asked respondents to choose between hypothetical primary care physicians described in terms of six attributes (three related to technical care and three related to interpersonal care). They found that physicians who were rated highly on technical aspects of care were selected more frequently than those rated highly on interpersonal aspects, and this did not differ by age, gender or ethnicity. This study used a task similar to DCE studies but a simpler design and analytic approach. Little et al.17 asked patients attending a GP appointment what they wanted from their medical encounter and using factor analysis identified three domains of patient preference (communication, partnership and health promotion) among the 21 questions (which were focused on patient‐centred care). They found communication aspects reported more frequently than other aspects, and this varied by health, employment and frequency of GP visits.17

In addition to the above approaches, a number of studies have inferred preferences from the analysis of associations between patient evaluation of different aspects of their care and satisfaction with that care. Among these, aspects of care quality have dominated. Paddison et al.18 found that doctor communication was more strongly associated with patient satisfaction with primary care than other measures of patient experience including helpfulness of staff and measures of care availability. There were statistically significant but small differences in the effect sizes by ethnicity, health status and age.18 Tung and Chang19 found that patient evaluation of the doctor's technical skill was the most important driver of satisfaction followed by interpersonal skill. In a study from the USA,20, 21 both waiting time in the doctor's office and time spent with the doctor were found to be important to satisfaction with a primary care physician, although the improvement in satisfaction associated with an additional minute spent with the doctor (3.78) was substantially greater than the decrement for an additional minute waiting (0.39). Fan et al.22 (also from the USA) found continuity was associated with satisfaction and this was the case for satisfaction with both the provider and the organizational aspects of care. This study also found that satisfaction increased with age and was higher for females, people with higher incomes and those reporting better mental health.22 A small Australian study23 also found associations between waiting time in the doctor's office and satisfaction with primary care.

Although the important factors for choosing a GP have been examined by a number of quantitative studies using a variety of methods, all have limitations. DCE studies can be cognitively challenging and are limited by the number of attributes that can be included in the experiment. To date, most DCEs have only included between three and nine attributes. Inferring preference for factors from the associations between satisfaction with components of services and general satisfaction with the service is limited by the components of the service assessed and interpretation of satisfaction, which has previously been found to be attributable to patient factors to a much greater extent than differences in services or satisfaction with components of services (see, e.g. Salisbury et al.24). Few studies (other than DCEs) have directly measured preferences for attributes of GP care, and only one of these examined the dimensions of care underlying preferences; this study included a limited range of attributes because its focus was patient‐centred care rather than GP care more broadly. In addition, few studies have examined preferences for GP care in the context of the Australian health‐care system.

This article reports a study investigating the important attributes for choosing a GP in Australia. It extends the existing literature by examining a comprehensive range of attributes of GP care and by assessing the extent to which these attributes can be grouped into underlying dimensions. It also explores the extent to which preferences are associated with individual health and demographic characteristics.

Methods

A survey of Australian adults aged 16 or more was completed online in July 2013 by members of a panel hosted by Pureprofile (http://www.pureprofile.com/au). The panel has a large number of account holders who have registered online to participate in surveys. Respondents are paid for each completed survey, according to the length of the survey. Information about the payment amount is included in the survey invitation, and the respondent chooses which surveys to complete. There are no inclusion/exclusion criteria for joining the panel except that panel members must be over 13 years of age. The invitation for the current study was only extended to panel members aged 16 or older.

The survey asked respondents to rate the importance of a range of doctor and practice attributes to their choice of GP. There were 36 attributes, each with the same 5‐point numeric response scale anchored at 1 = ‘not at all important’ and 5 = ‘extremely important’. The 36 questions are given in Table 1. Using the framework devised by Cheraghi‐Sohi et al.,1 the 36 questions covered access to care in general, access to preferred services, technical care, interpersonal care in terms of communication, continuity (informational and relational/interpersonal) and hotel aspects (such as waiting room and parking). Although some of the questions we have identified as interpersonal care may also be seen as relating to patient‐centredness (such as ‘the GP involves me in discussions about my treatment’), this aspect of the framework was not explicitly covered separately from the interpersonal care aspect.

Table 1.

Principal components analysis with oblimin rotation: items and factor loadings (n = 2481)

| Question (5‐point response scale: 1 = not at all important–5 = extremely important) | Factor loading | Response % 4 or 5 |

|---|---|---|

| Factor 1: Care quality | ||

| The GP gives me sufficient information on my condition and treatment options | 0.87 | 91.2 |

| The GP listens and explains the diagnosis and treatment clearly | 0.86 | 91.6 |

| The GP involves me in discussions about my treatment | 0.85 | 90.4 |

| The GP will conduct a thorough physical examination when necessary | 0.82 | 88.9 |

| The GP offers treatments proven to achieve results | 0.82 | 88.8 |

| The consultations with the GP are long enough to deal with my needs | 0.77 | 90.3 |

| I can see the same GP each time and she or he knows my medical history | 0.72 | 84.6 |

| I can see the GP of my choice | 0.59 | 83.8 |

| The practice is clean, and the staff are friendly | 0.58 | 91.1 |

| The GP has easy access to my computerized medical records | 0.57 | 83.2 |

| Factor 2: Types of services | ||

| The practice offers allied health services (such as physiotherapy) | 0.81 | 39.2 |

| The practice offers complementary and alternative health care (such as acupuncture) | 0.79 | 33.1 |

| The practice offers specialist nurses (such as diabetes care) | 0.74 | 42.9 |

| The practice offers home GP visits | 0.70 | 37.2 |

| I can choose whether to see the GP, GP assistant or practice nurse | 0.67 | 51.6 |

| The practice offers on‐site pharmacy and pathology services | 0.66 | 49.8 |

| The GPs in the practice have special expertise (e.g. women's health, child health) | 0.64 | 57.1 |

| The practice offers alternatives to doctor face‐to‐face consultations (e.g. phone, email) | 0.40 | 31.2 |

| Factor 3: Availability | ||

| I can make appointments out of hours (i.e. night, weekends, holidays) | 0.70 | 52.8 |

| I can make an appointment online | 0.66 | 30.6 |

| The practice provides urgent care out of hours (i.e. night, weekends, holidays) | 0.60 | 57.6 |

| The practice sends appointment reminders by phone/text/email | 0.58 | 37.0 |

| I can make a same day appointment | 0.54 | 70.6 |

| I can make an appointment to see a GP at a time of day that suits me | 0.45 | 80.9 |

| Factor 4: Cost | ||

| It costs very little to travel to each appointment | 0.87 | 68.3 |

| The practice is nearby | 0.82 | 78.0 |

| The practice offers bulk billinga | 0.54 | 81.9 |

| The doctor sees me promptly at the appointed time | 0.46 | 77.5 |

| The practice staff deal with the Medicare forms and I do not need to make a claim | 0.44 | 82.0 |

| The practice staff tell me whether the doctor is running late for my appointment when I arrive | 0.40 | 80.0 |

| Factor 5: Practice characteristics | ||

| The practice has more than one GP | 0.68 | 68.9 |

| The waiting room is comfortable | 0.60 | 70.6 |

| The practice is part of a larger medical group | 0.56 | 29.7 |

| There is parking nearby | 0.50 | 79.0 |

| The practice is accredited | 0.43 | 74.8 |

| There is public transport nearby | 0.41 | 42.1 |

Bulk billing means no patient co‐payment.

The survey also asked respondents about their experiences of GP care and usage, and included questions about health and socio‐demographic characteristics. The questionnaire was devised for this survey and drew on existing questionnaires such as the Australian Bureau of Statistics Patient Experiences in Australia Survey.25 The doctor and practice attributes were identified from the literature on consumer preferences in general practice, particularly studies using DCE methods, and modified for the Australian context. The questionnaire was pilot‐tested (n = 26) for clarity of language and interpretability and revised in response to respondent feedback.

Principal components analysis (PCA) was used to identify dimensions among the 36 importance items and to facilitate reduction to a smaller number of summated scales. PCA assesses the existence of underlying latent variables or domains. It examines the extent to which some variables form a coherent subset by correlating with one another while being largely independent of other subsets.26 PCA was conducted using SAS version 9.3: SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA. Oblimin rotation26 was used as some correlation among factors was expected, and it provided small improvements in interpretability of factors relative to varimax rotation. Items loading onto the same factor were interpreted as part of the same dimension, using factor loadings of 0.40 or greater. A five‐factor solution explained 57.7% of the variance in the 36 items and was selected based on the scree plot and interpretability of factors. The factor loadings are given in Table 1. One item loaded onto two factors; ‘The doctor sees me promptly at the appointed time’ loaded onto Factor 3 (0.41) and Factor 4 (0.46) and was interpreted with the latter. As expected, there was some correlation between factors; Factor 1 correlated with Factor 4 (0.46), and Factor 2 correlated with Factor 3 (0.37) and Factor 5 (0.42). Dimension scores were estimated as the mean of items loading onto the same factor (possible range 1–5).

The data were initially analysed to identify the individual items most frequently reported as important and unimportant and to examine the relative importance of the dimensions by comparing the mean dimension scores and their 95% confidence intervals (CI). Multiple regression analyses were then used to identify the respondent characteristics associated with each dimension score. The characteristics of primary interest were those relating to health, health‐care access and GP utilization; therefore, all models included age, an indicator for the existence of at least one chronic condition, self‐reported health status, GP visits in the past year, area of residence and concession status. The Australian government provides a range of concession cards linked to its various income support programmes some of which can also be accessed by low‐income families and retirees. Concession status was included because it can be an important determinant of access to free primary health‐care services. Other demographic characteristics were initially entered into the models but only retained if statistically significant; these included gender, education, income, marital status, having children aged <16, being born overseas, mainly speaking a language other than English at home, and whether or not the respondent was an informal carer.

As the dimension scores (described above) were calculated as the mean of individuals’ responses to multiple questions (6, 8 or 10 questions) measured on a 5‐point scale, the resulting scores were continuous variables and analysed using ordinary least squares (OLS) regression. Robust standard errors were used to account for heteroskedasticity in some of the dimension scores. Because each dependent variable was constructed from discrete variables, we used interval regression to check the sensitivity of the results to interval censoring (i.e. first four intervals are both left and right censored, and the last interval is left‐censored). We also used Tobit regression to assess the robustness of the linear regression to the right censoring evident in the care quality and cost dimension scores which had a large number of observations at the highest value (5). These three analytical methods found very similar results, so for ease of interpretability, the OLS regression with robust errors is reported. All regression analyses were conducted in Stata version 12: Statacorp, College Station, TX, USA.

Results

Of 2564 panel members who responded to the survey, 2481 completed the 36 questions on the importance of GP and practice attributes and were therefore included in the PCA. Because of missing data for some regression covariates, the sample sizes for the regression analyses ranged from 2303 to 2337 depending on the significant covariates included in the model. The sample characteristics are presented in Table 2 along with those for the Australian population. The sample was generally representative of the Australian population with the exception of health status, where people with a chronic disease who report their health as fair or poor were over‐represented. The majority of respondents lived in a major city (77%) which is similar to the Australian population (70%).

Table 2.

Sample characteristics

| Study sample (n = 2337) % | Australian populationa % | |

|---|---|---|

| Chronic disease | 61.5 | 44.8 |

| Health fair/poor | 29.9 | 13.1 |

| GP visits past year | ||

| 0 | 6.6 | 18.9 |

| 1 | 15.6 | 13.7 |

| 2–3 | 41.3 | 30.8 |

| 4–11 | 30.2 | 26.9 |

| 12 or more | 6.3 | 9.7 |

| Female | 52.5 | 50.6 |

| Age | ||

| 16–29 | 14.4 | 25.8 |

| 30–39 | 22.4 | 17.1 |

| 40–49 | 21.3 | 17.0 |

| 50–59 | 19.2 | 15.7 |

| 60–69 | 16.4 | 12.4 |

| 70 or more | 6.3 | 12.0 |

| Area | ||

| Major cities | 77.3 | 70.2 |

| Inner regional | 15.5 | 19.3 |

| Outer regional/remote | 7.2 | 10.5 |

| Concession statusb | ||

| None | 53.7 | |

| Health Care | 19.8 | |

| Pensioner | 22.9 | |

| Veterans’/Seniors | 3.6 | |

| Household income per annumc | ||

| Missing | 13.1 | |

| <$40 000 | 24.4 | 27.9 |

| $40 000–79 999 | 25.9 | 26.8 |

| $80 000–149 999 | 28.3 | 29.0 |

| $150 000 or more | 8.3 | 16.4 |

| Born in Australia | 73.5 | 70.6 |

| Mainly speak English at homed | 91.0 | 80.7% |

| Educational qualification since school (degree or trade) | 67.7 | 56% |

| Informal carer | 11.6 | 11.9 |

Australian Bureau of Statistics.

Australian population data not available for concession status.

Australian population data for nearest approximate categories.

Australian population data are percentage of all Australians aged 5 years or older who only speak English at home.

The five dimensions identified by the PCA were named according to the item content as follows: ‘care quality’ (10 items), ‘types of services’ (eight items), ‘availability’ (six items), ‘cost’ (six items including time and financial cost) and ‘practice characteristics’ (six items). The care quality dimension included questions intended to capture three aspects of care: interpersonal care, technical care and continuity (Table 1). The types of services dimension comprised a range of different services provided by or collocated with the practice (including alternatives to traditional care), capturing the preferred services component of access to care from the categories of Cheraghi‐Sohi et al.1 The availability dimension also covered components of access, including questions about the ease of access to appointments and the availability of out‐of‐hours care. The cost dimension covered further aspects of access to care, including access to free care, travel costs and time costs. The hotel aspects of care from the categories of Cheraghi‐Sohi et al.1 were primarily grouped under the practice char‐acteristics dimension which combined questions about the waiting room and parking with questions about practice size and structure. Cronbach's coefficient alpha demonstrated good internal consistency for the scales, ranging from 0.73 (practice characteristics) to 0.94 (care quality).

The highest mean dimension scores were for care quality (mean 4.45, 95% CI 4.43–4.47) and cost (mean 4.13, 95% CI 4.10–4.15), where a higher score indicates greater importance for choosing a GP. Types of services had the lowest mean score (mean 3.26, 95% CI 3.22–3.30), indicating that it was the least important dimension on average (Fig. 1). The individual items most frequently identified as important or extremely important (rated 4 or 5) were those making up the care quality dimension; the interpersonal care attributes (GP communication, information provision and length of consultation) were rated as important by 90–92% and the technical care attributes (thorough examination and use of proven treatments) were rated as important by 89% (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Mean dimension scores and 95% confidence intervals.

Co‐payments and patient contributions are common in Australian general practice, and within the cost dimension, the individual items most frequently identified as important were free consultations (called bulk billing1) and immediate claim submission for reimbursement of fees paid; both were identified as important by 80% of respondents. The individual items most frequently identified as not important were generally characteristics of the practice and contributed to the types of services, availability and practice characteristics dimensions; in particular online appointments, alternatives to face‐to‐face consultations and the availability of complementary/alternative health care were identified as not important by over 30% of respondents.

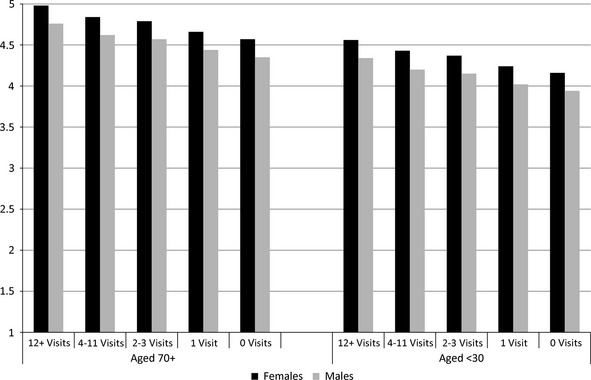

The regression analyses found no statistically significant differences by area of residence, the presence of a chronic disease or self‐assessed health status for any of the dimension scores, after adjusting for other covariates (including age and frequency of GP visits, see Table 3). All dimension scores were significantly higher for females and frequent GP users. On average, the dimension scores of females were between 0.14 and 0.22 points higher than those of males. All dimension scores were higher in frequent GP attenders (defined as the frequency of GP visits in the previous year); those with 12 or more visits had dimension scores between 0.33 and 0.41 points higher than those with no visits in the previous year (see Table 3). These effects are illustrated for the care quality dimension in Fig. 2. The individual characteristics explained 14% of the variance in the care quality dimension score but only 4–6% for the other dimension scores.

Table 3.

Regression models for the five summated scales

| Care quality (n = 2323) | Types of services (n = 2303) | Availability (n = 2323) | Cost (n = 2337) | Practice characteristics (n = 2316) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef. | 95% CI | Coef. | 95% CI | Coef. | 95% CI | Coef. | 95% CI | Coef. | 95% CI | |

| Chronic condition | 0.04 | −0.02, 0.09 | 0.00 | −0.08, 0.08 | −0.04 | −0.10, 0.03 | −0.02 | −0.07, 0.04 | −0.06 | −0.13, 0.00 |

| Health fair/poor | −0.02 | −0.08, 0.04 | −0.01 | −0.10, 0.08 | −0.02 | −0.10, 0.07 | −0.02 | −0.09, 0.05 | −0.05 | −0.13, 0.02 |

| Area (base = major cities) | ||||||||||

| Inner regional | 0.02 | −0.04, 0.08 | 0.02 | −0.08, 0.12 | −0.03 | −0.12, 0.06 | −0.06 | −0.13, 0.02 | −0.01 | −0.07, 0.09 |

| Outer regional/remote | −0.01 | −0.09, 0.07 | −0.02 | −0.16, 0.13 | −0.11 | −0.25, 0.03 | −0.06 | −0.16, 0.05 | −0.08 | −0.19, 0.04 |

| Concession status (base = none) | ||||||||||

| Health care | −0.04 | −0.10, 0.02 | 0.13** | 0.04, 0.23 | −0.02 | −0.09, 0.06 | 0.03 | −0.03, 0.10 | 0.10* | 0.02, 0.17 |

| Pensioner | −0.03 | −0.09, 0.04 | 0.18** | 0.07, 0.29 | −0.06 | −0.15, 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.00, 0.15 | 0.14** | 0.05, 0.23 |

| Seniors | 0.05 | −0.07, 0.17 | 0.35** | 0.12, 0.58 | 0.07 | −0.14, 0.28 | 0.19* | 0.03, 0.34 | 0.24* | 0.02, 0.46 |

| Veterans’ | −0.13 | −0.32, 0.07 | 0.09 | −0.21, 0.39 | −0.17 | −0.46, 0.13 | −0.20 | −0.43, 0.03 | −0.03 | −0.27, 0.21 |

| GP visits past year (base = 0) | ||||||||||

| 1 | 0.09 | −0.04, 0.21 | 0.11 | −0.05, 0.27 | 0.17* | 0.04, 0.30 | 0.11 | −0.02, 0.24 | 0.18** | 0.05, 0.32 |

| 2–3 | 0.22*** | 0.10, 0.34 | 0.17* | 0.02, 0.32 | 0.19** | 0.07, 0.32 | 0.18** | 0.06, 0.30 | 0.21** | 0.08, 0.33 |

| 4–11 | 0.27*** | 0.15, 0.39 | 0.14 | −0.02, 0.30 | 0.21** | 0.08, 0.35 | 0.21*** | 0.09, 0.34 | 0.25*** | 0.12, 0.39 |

| 12 or more | 0.41*** | 0.27, 0.55 | 0.33** | 0.11, 0.54 | 0.35*** | 0.17, 0.53 | 0.36*** | 0.20, 0.51 | 0.36*** | 0.19, 0.54 |

| Age (base = 16–29 years) | ||||||||||

| 30–39 | 0.08* | 0.00, 0.17 | 0.06 | −0.06, 0.18 | 0.00 | −0.09, 0.10 | 0.07 | −0.01, 0.16 | 0.06 | −0.03, 0.16 |

| 40–49 | 0.16*** | 0.08, 0.24 | 0.05 | −0.07, 0.17 | 0.00 | −0.09, 0.10 | 0.11* | 0.02, 0.20 | 0.02 | −0.07, 0.11 |

| 50–59 | 0.29*** | 0.21, 0.37 | −0.01 | −0.13, 0.12 | −0.08 | −0.18, 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.00, 0.18 | 0.01 | −0.09, 0.11 |

| 60–69 | 0.36*** | 0.27, 0.45 | 0.02 | −0.12, 0.16 | −0.07 | −0.19, 0.04 | 0.13** | 0.03, 0.23 | 0.05 | −0.06, 0.16 |

| 70 or more | 0.42*** | 0.31, 0.52 | −0.15 | −0.33, 0.04 | −0.14 | −0.30, 0.02 | 0.03 | −0.10, 0.16 | 0.04 | −0.12, 0.19 |

| Born overseas | 0.15** | 0.06, 0.23 | 0.12*** | 0.05, 0.19 | 0.10** | 0.03, 0.16 | ||||

| Language not English | −0.12** | −0.21, −0.04 | 0.18** | 0.06, 0.31 | 0.12* | 0.01, 0.23 | ||||

| Female | 0.22*** | 0.17, 0.27 | 0.20*** | 0.13, 0.28 | 0.15*** | 0.09, 0.21 | 0.18*** | 0.13, 0.23 | 0.14*** | 0.08, 0.19 |

| Qualification post‐school | −0.15*** | −0.23, −0.08 | −0.09** | −0.16, −0.03 | ||||||

| Informal carer | −0.16** | −0.27, −0.06 | −0.12** | −0.20, −0.03 | ||||||

| Constant | 3.94*** | 3.81, 4.06 | 3.27*** | 2.98, 3.55 | 3.30*** | 3.16, 3.43 | 3.78*** | 3.65, 3.91 | 3.62*** | 3.39, 3.85 |

| R 2 | 0.14 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.05 | |||||

Robust standard errors were used for all models.

*P < 0.05. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Figure 2.

Care quality: adjusted mean scores from regression model in Table 3. Visits = GP visits in the past 12 months.

In addition to the effects by gender and visit frequency, the care quality dimension was also significantly associated with age, where scores increased with age (see Table 3 and Fig. 2 which shows the oldest and youngest age groups). The types of services and practice characteristics dimensions were significantly associated with a number of respondent characteristics. People eligible for pension and other health‐care concessions (with the exception of veterans2) had higher scores for these dimensions relative to people without access to a concession card. People with a qualification since leaving school and informal carers had lower scores relative to those with no qualification and non‐carers, respectively (see Table 3). The types of services dimension were also associated with country of birth and language where people born outside of Australia, and those who speak a language other than English at home had higher scores relative to those born in Australia and English speakers, respectively. Similarly, the availability dimension showed higher scores for people born outside of Australia and those who speak a language other than English at home (see Table 3).

Discussion

This study examined the extent to which consumers rated factors as important for choosing a GP, using a large number of attributes of GP care and of the practice. It also examined the extent to which these attributes could be grouped together and identified five underlying dimensions. The dimensions we identified from the PCA do not separately represent the categories identified from the literature by Cheraghi‐Sohi et al.,1 in that the technical care, interpersonal care and continuity attributes all contributed to the same dimension (quality of care) and the attributes representing access to care in general contributed to two separate dimensions (availability and cost). The attributes representing access to preferred services contributed to a single dimension which we have labelled ‘types of services’ and the attributes related to hotel aspects also primarily contributed to a single factor which we called ‘practice characteristics’. Little et al.17 used similar methods to ours for identifying underlying dimensions; however, as the focus of their study was patient‐centred care, there is insufficient overlap in the questions included to compare the content of their dimensions with ours.

Care quality was found to be the most important dimension, and within this dimension, communication and information provision were the most important attributes. Cost was also an important dimension, and within this dimension, a free service or more rapid fee reimbursement were the most important attributes. The types of services dimension were the least important, which in part is likely to reflect the appeal of different services to different individuals. This dimension comprised a range of different services which might be provided by or collocated with the practice. Alternatives to face‐to‐face consultation and complementary/alternative health care were individual services most frequently identified as not important, which may reflect a lack of experience with these aspects which are not widely available.

The strength of importance of the different dimensions of important factors for choosing a GP varied among respondents. Frequent users of GP services and females placed greater importance on all dimensions relative to non‐users and males, respectively. Care quality was more important for older people who may have more clearly formed preferences than younger people due to more extensive experience of health‐care services and medical interactions. Types of services and availability were less important for Australian born people who speak English at home, while types of services and practice characteristics were less important for people who do not receive health‐care concessions, informal carers and those who have obtained educational qualifications since leaving school. There were no differences by health indicators apart from age and GP visit frequency, nor were there differences by rural or urban area of residence. It is possible that GP visit frequency provided a better indication of health condition than our health measures (the existence of at least one chronic health condition and self‐reported health status).

The results from this study are consistent with findings from much of the literature2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 18, 19 in that quality of care (including interpersonal care, technical care and continuity) was the most important dimension. However, the previous studies which examined multiple aspects of care quality found technical care to be the most important attribute; more important than interpersonal care16, 19 or continuity.2, 3 By contrast, we found a slightly higher proportion identifying interpersonal care attributes as important relative to technical care attributes. Cost was another important dimension in our study, and the ability to access a bulk‐billing (no charge to the patient) practitioner was one of the attributes contributing to this dimension most frequently rated as important. Although many studies have examined other aspects of access (most commonly waiting time), few have examined the importance of cost which to some extent reflects the health system in which the studies have been conducted (e.g. the UK where patients do not pay a fee). Two DCE studies from the UK included a cost attribute to assess the relative importance of technical care, continuity, waiting time and other attributes using willingness to pay; in both cases, the cost attribute was statistically significant.2, 3

The inability of our PCA to distinguish different aspects of care quality as separate dimensions suggests that either consumers do not have substantially differing preferences across the components of quality or that direct rating of importance is not a sufficiently sensitive method for capturing the differences. The direct rating was certainly able to distinguish different aspects of access to primary care, where three domains were identified: preferred types of services, cost and availability.

We found subgroup differences in the importance of the dimensions, but are limited in the extent to which we can interpret these in relation to other studies. Little et al.17 found that communication was more important for people with frequent GP visits which is consistent with our finding regarding the care quality dimension which includes communication. Paddison et al.18 found that the importance of doctor communication to satisfaction was higher for patients in poor health, those with a mental health condition and those living in a deprived area. By contrast, our measures of health and socio‐economic status were not significantly associated with the care quality dimension (which included communication), after adjusting for age and frequency of visits to the GP. Although many of the other studies discussed in the introduction found differences by respondent characteristics including age, gender, ethnicity, visit frequency and health status, the results are not directly comparable to ours because of the indirect assessment of the important attributes. The other satisfaction studies identified the impact of the characteristics on satisfaction rather than on the relationship between the service characteristics and satisfaction. The DCE studies can usually only interact a limited number of characteristics with each attribute which makes it difficult to identify a similar pattern, given our model adjustment.

Although the relevance of our findings to other health‐care systems will vary according to the particular health system, there were some consistencies with studies from other systems which suggest findings such as the emphasis on the importance of quality relative to availability2, 3, 6, 9, 10, 11, 12, 18 would be relevant elsewhere. For practitioners, this study emphasizes the importance of care quality and, in particular, good communication with patients about their condition and treatment options. Furthermore, the importance of care quality for patients choosing between GPs suggests that maintaining care quality would also be important to preserve existing patient–GP relationships. For policymakers, the study contributes to the evidence about consumer priorities and preferences for GP services and provides an indication of the types of information that people would find beneficial for choosing a new provider and that might potentially be made available for consumers. It also contributes information for the design of primary health‐care services, emphasizing the importance of the availability of a free service, particularly for people who see the GP frequently. The importance of care quality to patients, particularly over aspects of access, highlights this as an area of focus for monitoring the performance of existing primary care services and when reshaping future services.

The study has some limitations. Our survey methods may be less sensitive to differences in importance between aspects of care than other methods such as DCEs which force respondents to make trade‐offs across attributes. Nevertheless, we did identify differences in importance across dimensions and had the added benefit of examining a wider range of attributes within a single survey than would be possible using DCE methods. The sample includes more people with a chronic health condition and reporting poor health relative to the Australian population. While this might have contributed to an emphasis on care quality relative to other aspects such as availability or convenience, a chronic health condition was not significant in any of the modelled analyses when controlling for all the remaining covariates. It is also likely that the sample over‐represents people who speak English at home and regression models were adjusted for this if it had a significant effect. The sample is from an online panel, and it is possible that people who are not computer users, do not have Internet access or would not participate in an online panel differ on characteristics that we have not measured. Nevertheless, we do have a large sample which is similar to the Australian adult population on a number of characteristics.

This study reports the first stage in a broader investigation of the factors Australians deem important for choosing a GP. It identifies important attributes and dimensions of general practice for consumers. This can guide the information about practices that is available for consumers, particularly information about the quality of care which may be derived from patient experience surveys. Our results suggest that people will want to hear more about the manner in which care is delivered, rather than about the types of care that are available. The study also contributes information about preferred services which is useful for designing primary care services. Respondents varied in the importance given to some factors including types of services, suggesting the need for a range of alternative primary care services. The important attributes of GP care identified here will also inform the next phase of this research by contributing to the design of hypothetical practices for a DCE to assess the relative value of those attributes.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Research in the Finance and Economics of Primary Health Care Centre of Research Excellence (ReFinE‐PHC) under the Australian Primary Health Care Institute's Centres of Research Excellence funding scheme which is supported by a grant from the Australian Government as represented by the Department of Health and Ageing. The information and opinions contained in this study do not necessarily reflect the views or policy of the Australian Primary Health Care Research Institute or the Australian Government.

Notes

Where the GP bills Medicare (the government insurer) directly for each consultation.

Veterans’ concession is for eligible war veterans and former Australian Defence Force personnel and their dependents.

References

- 1. Cheraghi‐Sohi S, Bower P, Mead N et al What are the key attributes of primary care for patients? Building a conceptual ‘map’ of patient preferences. Health Expectations, 2006; 9: 275–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cheraghi‐Sohi S, Hole AR, Mead N et al What patients want from primary care consultations: a discrete choice experiment to identify patients’ priorities. Annals of Family Medicine, 2008; 6: 107–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hole AR. Modelling heterogeneity in patients’ preferences for the attributes of a general practitioner appointment. Journal of Health Economics, 2008; 27: 1078–1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Longo MF, Cohen DR, Hood K et al Involving patients in primary care consultations: assessing preferences using discrete choice experiments. British Journal of General Practice, 2006; 56: 35–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Philips H, Mahr D, Remmen R et al Predicting the place of out‐of‐hours care–a market simulation based on discrete choice analysis. Health Policy, 2012; 106: 284–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Scott A, Vick S. Patients, doctors and contracts: an application of principal‐agent theory to the doctor‐patient relationship. Scottish Journal of Political Economy, 1999; 46: 111–134. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Scott A, Watson MS, Ross S. Eliciting preferences of the community for out of hours care provided by general practitioners: a stated preference discrete choice experiment. Social Science and Medicine, 2003; 56: 803–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mengoni A, Seghieri C, Nuti S. Heterogeneity in preferences for primary care consultations: results from a discrete choice experiment. International Journal of Statistics in Medical Research, 2013; 2: 67–75. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gerard K, Salisbury C, Street D et al Is fast access to general practice all that should matter? A discrete choice experiment of patients’ preferences. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy, 2008; 13(Suppl 2): 3–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Turner D, Tarrant C, Windridge K et al Do patients value continuity of care in general practice? An investigation using stated preference discrete choice experiments. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy, 2007; 12: 132–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gerard K, Lattimer V, Surridge H et al The introduction of integrated out‐of‐hours arrangements in England: a discrete choice experiment of public preferences for alternative models of care. Health Expectations, 2006; 9: 60–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hjelmgren J, Anell A. Population preferences and choice of primary care models: a discrete choice experiment in Sweden. Health Policy, 2007; 83: 314–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rubin G, Bate A, George A et al Preferences for access to the GP: a discrete choice experiment. British Journal of General Practice, 2006; 56: 743–748. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Haas M. The impact of non‐health attributes of care on patients’ choice of GP. Australian Journal of Primary Health, 2005; 11: 40–46. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Razzouk N, Seitz V, Webb JM. What's important in choosing a primary care physician: an analysis of consumer response. International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance, 2004; 17: 205–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fung CH, Elliott MN, Hays RD et al Patients’ preferences for technical versus interpersonal quality when selecting a primary care physician. Health Services Research, 2005; 40: 957–977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Little P, Everitt H, Williamson I et al Preferences of patients for patient centred approach to consultation in primary care: observational study. BMJ, 2001; 322: 468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Paddison CAM, Abel GA, Roland MO et al Drivers of overall satisfaction with primary care: evidence from the English general practice patient survey. Health Expectations, 2013. Doi: 10.1111/hex.12081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tung Y‐C, Chang G‐M. Patient satisfaction with and recommendation of a primary care provider: associations of perceived quality and patient education. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 2009; 21: 206–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Anderson RT, Camacho FT, Balkrishnan R. Willing to wait?: the influence of patient wait time on satisfaction with primary care. BMC Health Services Research, 2007; 7: 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Camacho F, Anderson R, Safrit A et al The relationship between patient's perceived waiting time and office‐based practice satisfaction. North Carolina Medical Journal, 2006; 67: 409–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fan VS, Burman M, McDonell MB et al Continuity of care and other determinants of patient satisfaction with primary care. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 2005; 20: 226–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bolton P, Mira M. A comparison of morbidity and services provided in three primary care settings. Australian Health Review, 2003; 26: 26–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Salisbury C, Wallace M, Montgomery AA. Patients’ experience and satisfaction in primary care: secondary analysis using multilevel modelling. BMJ, 2010; 341: c5004. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c5004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Australian Bureau of Statistics . Patient Experiences in Australia: Summary of Findings, 2012–13. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using Multivariate Statistics. Boston: Pearson Education Inc., 2007. [Google Scholar]