Abstract

Aim

This study examined Latin American evaluation needs regarding the development of a collaborative mental health care (CMHC) evaluation framework as seen by local key health‐care leaders and professionals. Potential implementation challenges and opportunities were also identified.

Methods

This multisite research study used an embedded mixed methods approach in three public health networks in Mexico, Nicaragua and Chile. Local stakeholders participated: decision‐makers in key informant interviews, front‐line clinicians in focus groups and other stakeholders through a survey. The analysis was conducted within site and then across sites.

Results

A total of 22 semi‐structured interviews, three focus groups and 27 questionnaires (52% response rate) were conducted. Participants recognized a strong need to evaluate different areas of CMHC in Latin America, including access, types and quality of services, human resources and outcomes related to mental disorders, including addiction. A priority was to evaluate collaboration within the health system, including the referral system. Issues of feasibility, including the weaknesses of information systems, were also identified.

Conclusion

Local stakeholders strongly supported the development of a comprehensive evaluation framework for CMHC in Latin America and cited several dimensions and contextual factors critical for inclusion. Implementation must allow flexibility and adaptation to the local context.

Keywords: addiction, collaborative mental health care, evaluation, health services research, Latin America, mental health, mixed methods, primary care

Introduction

Latin America is facing the challenges of a growing epidemic of mental health issues representing 22% of the burden of disease.1 At the same time, this region has been a global leader in both building health systems with a strong base of primary health care (PHC)2 and community mental health services.3 Collaborative mental health care (CMHC) is being emphasized in most Latin American countries, and recent efforts from the World Health Organization (WHO)4 and the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO)5 are supporting those initiatives.

Globally, CMHC is defined in different ways. For this study in Latin America, CMHC is defined as providers from different specialties, disciplines or sectors working together to offer complementary services and mutual support to ensure that individuals receive the most appropriate and cost‐effective mental health service, and mainly in PHC. It considers high standards of quality and encompasses health promotion and early detection as well as diagnosis, treatment and recovery.6

Mental health1 represents an important public health challenge that requires a comprehensive and community‐oriented response.7 PHC offers a unique opportunity to provide better mental health care.8 Although there are different CMHC approaches being implemented, there is no comprehensive national or state/provincial evaluation framework for CMHC systems.8 That being said, there is a special interest worldwide, and in Latin America specifically, to identify the gaps between what is recognized as working well and what is practiced as CMHC.9, 10 An evaluation framework is needed to support these efforts.

Evaluation is the ‘systematic assessment of an object's merit, worth, probity, feasibility, safety, significance and/or equity' (p. 13, Ref. 11). Evaluating complex interventions – such as CMHC – requires a deep understanding of the context12, 13 and local needs.14 In this regard, working closely with stakeholders and evaluation users to identify their needs and to support them in using evaluation results is essential in collaborative evaluation strategies.15, 16, 17 Mixed methods research offers appropriate alternatives for health services research, including in PHC.18 Failure to attend to the needs and perspectives of stakeholders may be a serious limitation when designing and implementing an evaluation.15, 19

Needs' assessment is particularly useful when considering an innovative evaluation in PHC20 as this focuses attention on the future, or what should be done, rather than on what has been done in the past. It also reveals the different perspectives on community needs among key stakeholders.21 It is equally important when developing a CMHC evaluation framework to examine a full range of feasibility issues and potential ways to address them.22 Evaluation may be undermined by issues of acceptability, compliance, intervention delivery, recruitment and retention, among other factors.23

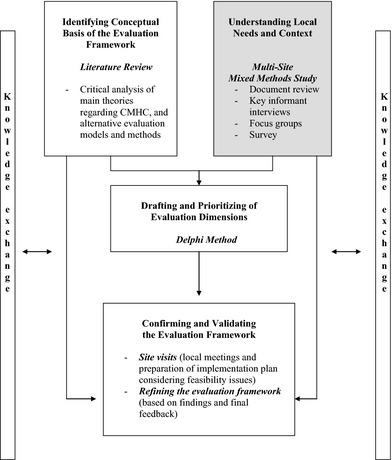

A research initiative has recently been implemented which aims to develop an evaluation framework that would support the on‐going improvement and performance measurement of services and systems in Latin America regarding CMHC. Figure 1 outlines the main research steps and methods of the overall study. As part of it, this article presents the component focused on understanding local needs and context in three research sites.

Figure 1.

Summary of Research Phases and Methods. Shaded is the data presented in this study. The Literature Review and Delphi Method results have been submitted as different manuscripts for publication.

Aims of the study

This article examines the identified evaluation needs, as well as potential implementation challenges and opportunities, as perceived by key health‐care leaders and professionals regarding the development of an evaluation framework in three CMHC systems located in Mexico, Nicaragua and Chile. As noted above, this research process was a critical first step of a larger initiative that aimed to develop an evaluation framework of CMHC at the district or municipal level in Latin America. This current study asked the following research questions:

What are the main mental health challenges in the context of Latin America and how does the local CMHC address them?

Considering the particularities of the context of Latin America, what are the evaluation needs perceived by local key health‐care leaders and professionals regarding the development of a CMHC evaluation framework aimed at informing decision‐making processes and improving PHC in the region at the district or municipal level?

What are some of the challenges and potential solutions to consider in the implementation of an evaluation framework for CMHC in Latin America?

Material and methods

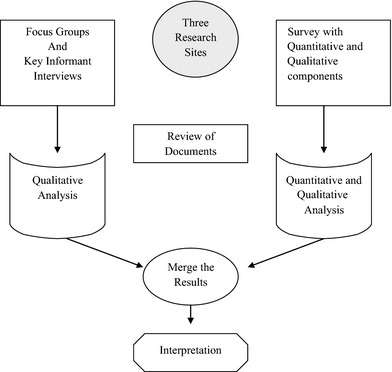

This is a multisite research study that used an embedded mixed methods approach24 including two parallel strands with the supremacy of the qualitative strand (Fig. 2). Three local health networks in the public sector in Latin America were purposively selected based on the following criteria: characteristics of the served population (e.g. size, rural/urban, levels of poverty, presence of indigenous communities); characteristics of the health‐care system (e.g. local CMHC approaches); geographical realities (Mexico, one country from Central America, and one country in South America); and feasibility criteria (e.g. local commitment of collaboration and availability of resources). The sites were as follows: (i) the Secretaría de Salud (Secretary of Health), State of Hidalgo, Mexico; (ii) the Sistema Local de Atención Integral Salud (SILAIS) (Local System of Comprehensive Health Care), in the district of León, Nicaragua2 ; and (iii) The Servicio de Salud Metropolitano Sur Oriente (SSMSO) (South East Metropolitan Health District), Santiago, Chile. Table 1 presents key characteristics of the research sites.

Figure 2.

Embedded Mixed Methods Design.

Table 1.

Overview of the three research sites and country context

| Research sites | |

|---|---|

| Secretary of Health of the State of Hidalgo, Mexico | A decentralized health network that provides services to the ‘open’ population of the state. This state, divided into 13 health jurisdictions and 84 municipalities, has a population of 2 396 201 inhabitants, and 53.1% of them living in rural areasa. More than 320 029 speak a native language. In 2002, the psychiatric hospital was replaced by community services ‘Villa Ocaranza’. There are 467 primary health‐care centres, 13 hospitals and specialized care units, including services for addiction (e.g. UNEMEs) and mental health (Villa Ocaranza). Advances primary mental health is provided at 84 Núcleos Básicos en Salud Mental (within primary care centres) and 3 Módulos de Salud Mental b |

| Leon Local Integrated Health System (SILAIS), León, Nicaragua. | One of the 17 SILAIS in Nicaragua, situated in the north‐west of the country. It is part of the Ministry of Health and works in coordination with the National Health Program (2010) which gives a strong role to primary health care. It serves the Leon Department that has a population of about 441 308 inhabitants, including indigenous groups (e.g. Subtiaba) in 138.03 km², with rural and urban areas distributed in 10 municipalities. Services are provided with a strong emphasis on primary care. There are 10 centres and other smaller units for PHC; one Centro de Atención Psicosocial (CAPS) – Centre for Psyco‐Social Care – that provides ambulatory mental health care with a community approach; and one general hospital and no mental health hospitalsc |

| South East Metropolitan Health District, Santiago, Chile | One of biggest of the 29 health districts in Chile. It provides public services in the context of 3 subnetworks and 7 municipalities in the south‐east area of the Chilean capital under the umbrella of the Ministry of Health. There are 1 500 651 inhabitants (22.6% of the metropolitan population) in the assigned territory and around 76.5% of them have public insuranced. Mental health services follow a community network‐based approach.e There are about 40 primary care centres (e.g. CESFAMs), 7 specialized community mental health facilities (COSAMs), 3 specialized mental health outpatient facilities (CRS and CDT), one mental health hospital (El Peral) and mental health beds within the general hospitalf |

| Countriesg | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Socio‐demographics and health indicators | Mexico | Nicaragua | Chile |

| Population in 2010 (millions) | 112.3 | 5.9 | 17.1 |

| Poverty rate % (year) | 47.4 (2008) | 44.7(2009) | 15.1 (2009) |

| GINI coefficient | 48.3 (2008)h | 40.5 (2005)i | 52.1 (2009)n |

| Literacy rate (%) (2010) | 93.1 | 96.6 | 98.6 |

| Political organization of the territory | The Federal District plus 31 states, 2638 municipalities | 15 departments, 2 autonomous regions, 153 municipalities | 15 regions, 53 provinces, 346 communes |

| Life expectancy at birth (years) (2010) | 76.7 | 74.5 | 79.0 |

| Infant mortality rate (per 1000 live births) | 14.9 (2009) | 29.0 (2006) | 7.9 (2008) |

| Budget for health as a % of the GDP | 6.9 (2009) | 5.41j (2009) | 8.3 (2009) |

| Budget for mental health (% of health budget) | 2k (80% of it for psychiatric hospitals) | 1 l (91% of it for psychiatric hospitals) | 2.14m (33% of it for psychiatric hospitals) |

| Provision of health services | Segmented health system with four components: public institutions for uninsured population (e.g. Servicios Estatales de Salud – SESA), IMSS‐Oportunidades, social security institutions (IMSS, ISSSTE, Seguro Popular de Salud – SPS) and the private sector.n | Mainly public. The public sector is made up of the Ministry of Health (65% of coverage), the medical services of the Army of Nicaragua and the National Police Force, and the Nicaraguan Social Security Institute (INSS). The country offers a national health policy that promotes a multisectoral approach to dealing with health issues. In 2007, the country started the implementation of the family and community health model (MOSAFC)o | Segmented health system with a public component that serves around 75% of the population and a private one.p PHC works with a family and community health approach and is managed by municipalities in coordination with health districts. Beginning in 2000, a health reform was implemented. It includes the AUGE Plan, a regime of explicit guarantees (access to treatment, opportunity, quality and financial protection) for prioritized conditions, including some mental health issues |

See Ref. 44.

Based on the information collected during the site visit on December 2010.

Based on the information collected during the site visit on February 2011.

See Ref. 45.

See Ref. 46.

See Ref. 47.

Main source of information: PAHO (2012) Otherwise, additional sources are indicated (see Ref. 48).

See Ref. 49.

World Bank.

See Ref. 50.

See Ref. 51.

See Ref. 52.

See Ref. 53.

See Ref. 54.

See Ref. 55.

See Ref. 56.

Data collection

Data were collected at the three research sites between December 2010 and April 2012 and included: (i) key informant interviews and focus groups and (ii) an online survey for other key stakeholders related to the CMHC system (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of the data collection process

| Research site | Individual interviews | Focus groups | Survey questionnaires |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mexico | 9 | 1 (n = 12) | 9 |

| Nicaragua | 6 | 1 (n = 7) | 10 |

| Chile | 7 | 1 (n = 6) | 8 |

| Total | 22 | 3 | 27 |

| Specific characteristics of interviews participants | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Type | Interviews | |

| Roles | Health director (e.g. secretary) of the district/municipality and/or the person who represents that authority | 5 (22.7%) | Mexico: 2 |

| Nicaragua: 1 | |||

| Chile: 2 | |||

| Mental health coordinator or CMHC coordinator of the district/municipality | 7 (31.8%) | Mexico: 2 | |

| Nicaragua: 2 | |||

| Chile: 3 | |||

| Other key informants who are involved in CMHC, according to the context | 10 (45.5%) | Mexico: 5 | |

| Nicaragua: 3 | |||

| Chile: 2 | |||

| Profession | Physicians (psychiatrist and non‐psychiatrists) | 16 (72.7%) | Mexico: 7 |

| Nicaragua: 5 | |||

| Chile: 4 | |||

| Psychologists, social workers and nurses | 6 (27.2%) | Mexico: 2 | |

| Nicaragua: 1 | |||

| Chile: 3 | |||

| Gender | Female | 13 (59.1%) | Mexico: 7 |

| Nicaragua: 2 | |||

| Chile: 4 | |||

| Male | 9 (40.9%) | Mexico: 2 | |

| Nicaragua: 4 | |||

| Chile: 3 | |||

Key informant interviews and focus groups. Twenty‐two semi‐structured key informant interviews were conducted – between six and nine interviews per site. Interviewees included the following: (i) the health directors of the local health networks; (ii) the mental health coordinator or CMHC coordinator of the local health networks; and (iii) one to three other key informant(s) who had key roles in CMHC, according to the context. In addition, one focus group was conducted in each of the three sites and participants (6–12 per site) were clinicians and managers from different professions working in CMHC, mainly in PHC. A ‘snowball’ purposive sampling technique was used to recruit participants, whereby the main local contact helped in suggesting potential participants.

An interview guide was developed beforehand to ensure that all areas of interest were covered, including the following: (i) mental health population needs; (ii) local CMHC system; (iii) key players/decision‐makers and collaboration areas; (iv) existing evaluation initiatives; (v) evaluation and information needs; (vi) vision of an evaluation framework for CMHC; and (vii) challenges and opportunities regarding implementing evaluation. The interviews were conducted in Spanish. Most of the questions were open‐ended. Potential respondents were approached by the local liaison person and then fully informed and recruited by the research team. The interviews and focus groups were audio‐recorded and then transcribed verbatim for the analysis. The researcher also took notes. Translation into English was undertaken by two bilingual members of the research team – the first author being a native Spanish speaker.

Survey. An online survey was conducted with other key stakeholders involved with the CMHC system, including mental health and substance‐use services, social welfare, corrections, and NGOs, depending on the context. In contrast to the interviews and focus groups, the emphasis in the survey was on non‐health sector actors and community organizations. The stakeholders and respondents were defined during the site visit, as a result of an environmental scan. The questionnaires were completed online in Spanish after consent was provided. Three reminders were sent. The questionnaire included closed and open‐ended questions and covered the same topic areas as the interviews/focus groups, giving special attention to CMHC system issues. The instrument was pilot‐tested – mainly for face and content validity – with three local health professionals/experts per research site (nine in total), who judged the appearance, relevance and comprehensiveness of the questionnaire, as well as the readability, clarity and phrasing of the items. Based on their feedback, some adjustments were made for the final version of the instrument. Twenty‐seven participants responded (overall response rate = 54%) – nine from Mexico, eight from Chile and 10 from Nicaragua – and represented a good cross section of community services and sectors.

Key local reports regarding population needs with respect to mental health and substance‐use CMHC and other related issues were reviewed beforehand to support the site visits. Those documents were helpful for a better understanding of the context, in particular to help tailor the questions of the interviews, focus groups and questionnaires to the reality of each site, when needed.

Analysis

Data were analysed within site and across sites. NVivo 9 Software was used for the analysis of the qualitative component and IBM SPSS Statistics 20.0 for the quantitative items. The analysis of qualitative data considered a framework analysis approach 25 using a priori codes (pre‐defined categories) and also inductive codes according to responses and emerging categories. Main areas of consensus and disagreements among local stakeholders about the features of an evaluation framework for CMHC in Latin America were identified. A SWOT analysis framework (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats)26 regarding an evaluation of CMHC in Latin America also helped to guide the analysis. Descriptive statistics (e.g. frequencies, means) were applied to the quantitative survey data.

Within the time and resource constraints of the project, we also aimed to address various criteria associated with ‘trustworthiness’ in a mixed method design.27, 28 Such criteria include prolonged engagement (accomplished through a 3‐year research process that included two field visits at each research sites, and on‐going communication with the liaison person at each site); persistent observation (accomplished through the site visits); triangulation (accomplished by cross‐referencing key themes in the analysis and seeking convergence and corroboration across the multiple methods of interviews, focus groups and survey); member checks (accomplished by a knowledge exchange follow‐up meeting in each of the sites that helped verify and better interpret data and to discuss the implications of the results); and reflexive journaling (accomplished by field notes, documenting the entire research process and regular meetings and debriefing with the research group).

Ethics

The study was approved by the University of Toronto's Research Ethics Board. When necessary, it was also approved by other institutional ethical review boards at the research sites (Nicaragua and Chile). Special efforts were implemented to ensure respondent confidentiality and to affirm that participation was voluntary.

Results

The findings3 are presented in four subsections: (i) understanding community context, including mental health and substance use at the population level, the local CMHC system response and existing evaluation initiatives; (ii) evaluation and information needs; (iii) vision of an appropriate evaluation framework for CMHC in Latin America; and (iv) implementation considerations. Because there were many commonalities among the research sites, the information from the three sites is integrated and differences among them are noted.

Collaborative mental health care in context

Mental health and substance‐use issues at the population level

According to the participants, mental illness and substance‐use issues were identified as equally relevant. The most important mental health problems noted were mood and anxiety disorders, schizophrenia and personality disorders. Phobias, attention deficit and hyperkinetic disorders were also identified as relevant, but were cited less often. Participants identified alcohol, tobacco, marihuana, cocaine (cocaine hydrochloride, crack and coca paste), inhalants and some prescription medications (e.g. benzodiazepines and amphetamines) as the main substances of abuse.

Participants gave particular attention to violence in different forms, including violence against women, maltreatment of children, politically related violence, gang violence and violence in the school (e.g. bullying). They pointed out the relationship between violence and drug use. Respondents in all three sites, but particularly in Leon, considered suicide and suicidal behaviour among youth as requiring urgent attention.

Suicide is another public health problem. We are dealing with a relatively young population, between 15 and 20 years of age. (Nic_ Int_4)

…they attempt suicide, some succeed, if not, they escape into smoking, drinking and taking drugs. Most importantly, this young and vulnerable population does not have the support of family or friends. (Nic_Int_3)

There were some differences in whether epilepsy is included in the scope of mental health issues. It is classified as a mental health problem in Mexico and Nicaragua, but in Chile, it is dealt with by neurological services. Autism spectrum disorders and intellectual disabilities were not identified as main priorities in the mental health context. However, somatic symptoms related to mental health issues were seen as particularly relevant and participants noted that patients tend to present multiple physical complains that may be hiding mental health problems. Co‐occurring substance use and mental disorders were also mentioned as challenges faced by the health services.

…normally out of every ten patients ….that have an addictive illness, no matter what substance they are addicted to….seven of them have a psychiatric co‐morbidity. (Mex_Int_5)

There was a strong consensus that social environmental factors such as poverty, income inequalities, unhealthy relationships, housing problems, war and natural disasters are important determinants of mental health and substance‐use problems. Further, in all three sites, stigma toward people with mental health and/or substance‐use problems was said to be associated with a worse prognosis in that it limits seeking care and promotes isolation.

the phenomenon of mental illnesses is still seen as a stigma, as a punishment, as a source of shame and so people always try to deny that they have this problem or try to hide those who are sick. We have found people who have suffered absolute violation of their human rights, practically confined to an inhuman life, chained down or hidden away so there was no contact between them and the outside world. (Mex_Int_2)

Survey results also supported the importance of stigma: 50% or more of the respondents in the three sites indicated that challenges related to stigma and discrimination against people with mental health and/or addiction problems are high or very high in their communities.

The local CMHC system response: Current progress and activities

Participants in interviews, focus groups and surveys across all sites highly valued CMHC, but reported different experiences in developing their health systems in this regard.

Hidalgo has been developing the ‘Hidalgo's Mental Health Model’ since the 1980s. In 2000, the old psychiatric hospital was closed and villas and two halfway houses were opened in Hidalgo. They were said to have an explicit approach to address mental health and substance‐use problems in the State, with an emphasis on PHC. However, participants reported challenges in implementation due to limited resources.

The SSMSO in Santiago was said to have a strong history of developing community mental health services, and more recently, a family health model is being implemented in PHC. The family health model includes intake, spontaneous consultations and referring people to various services. Explicit protocols were noted for addressing specific mental health issues in PHC and guiding referrals within the health network.

In Leon, the emphasis was said to be on implementing the Modelo de Salud Familiar y Comunitaria – MOSAFC4 – and facilitating universal access to care. Mental health was considered part of holistic health; there was less consensuses on the need to develop explicit conceptualizations and services regarding CMHC. A challenge noted was not having enough qualified persons to work in PHC.

There was clear agreement in the three sites regarding the importance of fostering access to mental health and addiction services, with an emphasis on PHC and the full continuum from health promotion to rehabilitation and recovery. The support for families facing mental health challenges was considered to be limited and that health services should do more to integrate and provide care to them. Gender‐based services targeting particular groups, such as pregnant women, were identified as a priority, as well as community outreach services.

Some of the challenges of CMHC on which there was agreement across the three sites were lack of financial resources and training of health professionals and limited access to psychotropic and evaluation. These limitations were said to affect access and quality of care.

Existing evaluation initiatives

While participants in all sites noted the existence of some evaluation activities (most involving high‐level monitoring with statistical indicators), they noted challenges with poor health information systems and lack of attention to mental health in these systems. Recent efforts to include mental health were noted and supported by the advent of electronic clinical records in some PHC centres. The main evaluation focus was said to be on processes, specific programmes/services (e.g. depression programme in Chile, or CAPs5 in Nicaragua) and/or the individual performance of health workers. Clinical supervision (e.g. by psychiatrists going to PHC) was considered to be an on‐going quality control/evaluation strategy.

Identified evaluation needs

All participants considered it important and necessary to evaluate CMHC.

{the evaluation is} ‘very useful because it will allow us to identify what lies beyond our vision of the iceberg, everything that is down below, certainly it will allow us to reorient ourselves in decision‐making’. (Mex_Int_3)

… we have to go from the gaps in meeting needs to the quality of attention. I believe we have advanced in extending coverage, in the provision of services. But what is this attention like and is this attention really effective, these are the questions we haven't answered. (Chi_Int_3)

Seven main themes of needs emerged: population needs, access, human resources, processes of care, impact, family involvement and support, and equity and human rights.

First, a profile of the population needs in each location was seen as essential to evaluate CMHC. This included having a clear sense of the dynamic epidemiological situation and population‐level information about environmental and social conditions, as well as the profile of CMHC users, including socio‐demographic, health status and diagnostic information.

We need to know the epidemiological situation that allows us to identify risk groups…, but we also require more information regarding the determinants. (Mex_Int_3)

Second, a clear picture of access to CMHC was a priority area for inclusion in an evaluation framework. Key identified subthemes were availability, accessibility (e.g. geographic), affordability (e.g. free of charge) and acceptability of services, including equitable access to quality care in PHC and how well existing services match client needs.

not everybody have access to a diagnosis neither to medications. (Nic_Int_6)

because of the geography of our State, it may be that somebody living in a remote area faces access to care issues…. Costs of services for patients, even when they are very low, may represent a barrier for some families. (Mex_Int_3)

Human resources (e.g. the type and number of professionals in relation to the population size and needs) were consistently identified as a critical dimension for an evaluation framework. There was strong interest in assessing competencies to address mental health and substance‐use issues, mainly in PHC. In addition, the evaluation of self‐care practices was recommended:

mental health service is required at the institutional level, a mental hygiene. There is a lot of burnout. (Mex_FG)

Processes of care were mentioned as being relevant to an evaluation framework and in terms of what happens to patients once they access care; quality and appropriateness of available services; and options, barriers and opportunities that patients face when navigating CMHC. Participants noted the importance of assessing both clinical and non‐clinical services (e.g. health promotion). More than just focusing on specific events, they noted that the evaluation should assess the overall process of care and its results. This included paying special attention to the referral systems, the level of adherence to treatment and why people continue with treatment or not. Having a system approach (e.g. identifying secondary and tertiary level services and the interconnections among the different levels of care) was also identified as a priority.

Continuity in health care… there could be an emphasis on results, what happens to people that have depression that go a health centre at 6 months, a year, 2 years. (Nic_Int_3)

Participants agreed on the importance of measuring the impact of CMHC results, including reduction in symptoms, improvements in quality of life and social reintegration, but did not think that this was necessarily the most important component of a framework. In particular, they were interested in assessing the perceptions of results among key stakeholders, including overall satisfaction from the users' perspectives.

Family involvement and support was also mentioned as relevant for evaluation.

How can we evaluate the levels of participation of the family? Because I feel the family support network is a determining factor in treatment of this kind. (Mex_Int_7)

… how does the family see mental health in its health context? Probably the family does not see it as an illness but rather the family thinks that illness is dengue fever or something like that. We have to see if the population perceives mental health as something important. (Nic_Int_5)

Participants noted that equity and human rights should be included in an evaluation framework: how CMHC integrates ethno‐cultural (e.g. indigenous populations/rural–urban/alternative local practices), equity and human rights approaches.

They {indigenous people} do not use the medical facilities of the Ministry of Health. Their first contact with health problems is the traditional healer or traditional doctor. (Nic_Int_ 4)

I don't know if today we know whether there is an equity focus or if there is a focus on gender, and when I talk about the evaluation I am speaking beyond access, beyond opportunity, I am talking about how much we concern ourselves with the individual. (Chi_Int_6)

More than other health problems mental health problems have to do with human rights. And human rights have to do with being human beings and having the right to be treated as one and not as merchandise. (Nic_Int_5)

Finally, some respondents considered it relevant to include existing information systems in the evaluation framework (e.g. what is required to be registered locally, what indicators are presently used, and how appropriate are they). The quality of clinical facilities was also mentioned as important, and a few participants focused on the importance of equipment or other infrastructure (e.g. availability of psychometric tests).

Vision of an appropriate evaluation framework for CMHC in Latin America

The majority of the research participants at the three sites fully supported the idea of having a comprehensive CMHC evaluation framework for Latin America – all indicating that an evaluation framework is either important or very important, and highly supported a comprehensive approach (Table 3). They gave strong endorsement to the inclusion to the following potential components: needs, structure and inputs, process of care, CMHC products, short‐term and long‐term outcomes, and impact. They also valued having other less traditional components, such as openness to innovation and capacity to respond to community and organizational change. Their vision included the full spectrum of services and supports ranging from health promotion, prevention, early recognition and diagnosis.

Table 3.

Perceived importance of evaluating different features of CMHC. Results from the survey of stakeholders in Mexico, Nicaragua and Chile. Means, standard deviations and ranges

| Needs (e.g. mental health/addiction characteristics and needs of the population in context) | Structure (e.g. infrastructure, organization, components and units of services) and Inputs (e.g. human resources, equipment, costs) | Process of Care (e.g. access, care practices from health promotion to treatment and rehabilitation, continuity of care) | Products and Short‐term Outcomes (e.g. number of attentions, number of screenings/reduction in symptoms) | Impact Outcomes (e.g. mental health, overall health, quality of life, equity) | Others (e.g. openness to innovation, capacity to respond to changes.) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mexico (answered by n = 8) | Mean: 4.63 | 4.63 | 4.75 | 4.38 | 4.38 | 4.25 |

| SD: 0.70 | 0.48 | 0.43 | 0.86 | 0.70 | 0.83 | |

| Range: 3–5 | 4–5 | 4–5 | 3–5 | 3–5 | 3–5 | |

| Nicaragua (answered by n = 9) | 4.44 | 4.33 | 4.78 | 4.22 | 4.44 | 4.33 |

| 0.50 | 0.47 | 0.42 | 0.42 | 0.50 | 0.82 | |

| 4–5 | 4–5 | 4–5 | 4–5 | 4–5 | 3–5 | |

| Chile (answered by n = 7) | 4.43 | 4.29 | 4.71 | 4.71 | 4.71 | 4.57 |

| 0.49 | 0.70 | 0.45 | 0.45 | 0.45 | 0.49 | |

| 4–5 | 3–5 | 4–5 | 4–5 | 4–5 | 4–5 | |

| Total | 4.50 | 4.42 | 4.75 | 4.42 | 4.50 | 4.38 |

| 0.58 | 0.57 | 0.43 | 0.64 | 0.58 | 0.75 | |

| 3–5 | 3–5 | 4–5 | 3–5 | 3–5 | 3–5 |

The scale goes from 1 (very low importance) to 5 (vey high importance).

…it should be as integral as possible: the capacities of different health care professionals that participate; the real collaboration among institutions and organizations; the health care delivery capacity…. (survey)

Researcher respondents identified concrete benefits of having an evaluation framework including the following: informing decision‐making processes, supporting the search for funding, tailoring CMHC according to needs, improving the quality of care, orienting the system to positive mental health and quality of life results and management of the limited existing resources for CMHC.

Implementation considerations

The heads of the three local health networks expressed their commitment to a CMHC evaluation framework. Other participants in the three sites identified some level of openness on the part of local authorities to support a CMHC evaluation framework, but also having some reservations about using it.

I think that in the discussion there is willingness, but this has to be compared to the reality. (Chi_FG)

Interview and focus groups participants thought it is perfectly feasible to have one evaluation framework for the Latin America region noting that it would facilitate learning from others experiences and offer comparative benchmarks. Still, it would need to be adjusted to local realities.

Table 4 summarizes the main strengths and challenges noted by participants with respect to implementing a CMHC evaluation framework in the three research sites. Overall, participants identified opportunities for implementing a framework and perceived a positive momentum to take it forward:

Table 4.

Main identified strengths and barriers for implementing an evaluation framework for CMHC

| Mexico | Nicaragua | Chile |

|---|---|---|

| Strengths | ||

|

Local collaboration Local universities Existence of a ‘Norma Oficial Mexicana’ to guide clinical care On‐going training Local human resources |

Family and community health model Inter‐institutional work Interest on evaluation Local collaboration Local universities On‐going training Committed local human resources |

Long experience of developing community mental health Strong public primary care Local collaboration Local universities On‐going training Local human resources |

| Barriers/Limitations | ||

|

Weak culture of evaluation Lack of time Risk of ‘penalizar’ (‘punishment’) Lack of local capacity for analysis Limited information systems |

Weak culture of evaluation Lack of time Lack of training in evaluation Risk of ‘penalizar’ (‘punishment’) Lack of local capacity for analysis Limited information systems |

Weak culture of evaluation Lack of time Potential initial barrier at the front line (related with the fear of changing) Limited information systems |

I think there are strengths to develop it, there is a lot of willingness. It is an urgent topic…There is a great need to be able to intervene and I believe that is feasible. (Nic_FG)

Two critical considerations were identified by respondents regarding the feasibility of implementing an evaluation framework:

Fear of evaluation: ‘People hear “evaluation” and they panic. Or they are afraid or they start thinking what are they going to evaluate in me, are they going to classify me, are they going to call into question my participation and activities, what I am doing as a health professional’. (Mex_Int_5)

Resistance to change: ‘making new things equal implies expending a little more energy and it there that we get somewhat stuck all of a sudden'. (Nic_Int_3)

Participants indicated that an evaluation should be accompanied by capacity building with respect to implementation, in particular ensuring appropriate economic and human resources. They also remarked on the importance of building/strengthening information systems to ensure the availability of data required for evaluation.

Discussion

The study findings provide valuable information from three local contexts regarding the development and potential implementation of a meaningful CMHC evaluation framework in Latin America and reflect the high level of interest and support among decision‐makers, clinicians and other stakeholders for such a framework. The results suggest that an evaluation framework should be comprehensive, including a focus on needs, processes and outcomes, but also be responsive to other values‐based aspects, including culture, diversity, gender and human rights. The importance of capturing the voice of clients and family members in the evaluation and assessing how their CMHC expectations are addressed was also seen as critical and reflective of the literature in this area.18, 29 An integrated approach that covered the full range of health promotion, prevention, early recognition and diagnosis and treatment was also widely supported.

Along with strong support for the development of a comprehensive30 CMHC evaluation framework in Latin America, there was a clear call for recognition of the multiplicity of existing CMHC systems/approaches and levels of implementation in different jurisdictions. The need for flexibility in performance measurement processes is consistent with existing literature.31, 32 The inclusion of core and optional evaluation dimensions, as well as a ‘basket’ of performance indicators from which to choose according to each local context, would be an appropriate strategy in this regard.

Access to CMHC was recognized as a priority dimension to consider in an evaluation framework. This is in line with the available information regarding existing gaps of mental health services8, 33 as there are many jurisdictions where mental health services are extremely limited.4, 34 Availability of services becomes an essential area to measure, but other aspects of access such as geographic accessibility and affordability should be also assessed.35

This is the first study of its kind in Latin America and has many methodological strengths. The research design included the core characteristics of a mixed methods approach28 in a rigorous way to address the stated research questions. Participants were drawn from within CMHC as well as other associated sectors and services.

Potential limitations

The strengths of the study, notwithstanding some difficulties, arose due to the complexity of CMHC36 and potentially different understandings of key concepts. A special effort was made to explain the focus of the research on CMHC with sufficient detail and to clarify questions and concepts when needed.

Because of resource limitations, the study could not cover additional countries/sites in Latin America, including other large and important jurisdictions such as Brazil. It is important to mention that the research study focuses on health districts or provinces, but not countries per se. In that sense, the three sites represent a good qualitative sample of CMHC in the region and the study provides a framework and an approach that could be replicated in other jurisdictions to corroborate the findings.

Each data collection method (i.e. interviews, focus groups and survey) has its own limitations.37, 38 To minimize the potential impact of these limitations, several data sources were considered, along with rigorous and systematic data collection methods, appropriate analysis of data and an overall mixed methods approach. However, a note of caution is needed when analysing and interpreting quantitative data from a survey with a small sample and relatively low response rate. That being said, in the context of purposive sampling in a mixed methods study, the size of the sample is less relevant (but still important) than in a project relying solely on quantitative survey data.

Logistical and ethical research challenges (e.g. confidentiality issues) as well as resource limitations did not allow for incorporating community members with mental health issues, or their family members, directly in the research process. However, special efforts were made to capture their reality during all the stages of the data collection and analysis. The survey did include representatives of community organizations, such as youth and municipal organizations, and these individuals are in close contact with clients and their family members.

Implications

Community needs are dynamic and change over time and may vary according to individual perceptions, interpretations, values and differing circumstances.39 Identifying needs is relevant for developing and evaluating health services and CMHC in particular. An evaluation framework for CMHC in Latin America must consider all the aforementioned factors, as well as the local context and transformational processes within it. The framework should be applicable to evaluate different prototypes of CMHC in Latin America in the future, with the necessary contextual adjustments.40

To progress in designing the evaluation framework for CMHC existing relevant theoretical models41 and methodological considerations should be analyzed in the context of the identified needs and feasibility issues in Latin America. One critical step towards developing the framework will be the precise definition of its main dimensions and core indicators. These require agreement on content, applicability in the framework and validity in the real world of health care. Indicators should be evidence‐based, sensitive to change over time, reproducible and relatively easy to collect. A Delphi group with regional experts is a natural next step to identify the main areas of consensus and disagreement. That step has been already conducted as a component of the overall research project.42

This study represents an opportunity to strengthen health services and evaluation research to support innovative policies, while enhancing social inclusion and multistakeholder participation in decision making related to health‐care improvements. The presented findings are aligned with other existing evaluation frameworks, such as the WHO Quality Rights Initiative, but they add a unique Latin America PHC perspective. The development of a feasible and needs‐based evaluation framework for CMHC may facilitate public accountability and contribute to improve access and quality of care for people who suffer mental illness and/or addiction problems. A framework is key in evaluating the on‐going processes and outcomes17, 43 of collaborative care initiatives, enabling reporting of many dimensions of performance across jurisdictions and over time. A framework will help assess the attainment of goals established for both PHC and mental health/substance use, as well as for renewal of the broader health system.

Declaration of interest

No conflict of interest.

Source of funding

Doctoral Research Award, Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR).

Acknowledgements

This work formed part of the PhD dissertation for Jaime C. Sapag and he warmly thanks other members of his PhD Advisory Committee: Professors Cameron D. Norman and Jan Barnsley. He also would like to thank Professor Ted Myers for his support, as the head of the PhD programme at Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto. We wish to express special thanks to several individuals and groups for their guidance, expertise and/or support, including the following:

Director of Office of Transformative Global Health at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH): Akwatu Khenti

Key liaisons at the three research sites: Ana María Tavarez (Mexico), Andrés Herrera (Nicaragua) and Ana Valdés (Chile)

Advisory Committee members and Delphi panellists

Individuals who participated in the data collection process at the study sites

- Institutions and programmes that supported the implementation of the PhD thesis:

-

iSecretary of Health of the State of Hidalgo, Mexico

-

iiThe Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Nicaragua‐León and its Centro de Investigación en Demografía y Salud (CIDS), as well as the Sistema Local de Atención Integral de Salud in León, Nicaragua (SILAIS‐León)

-

iiiSouth East Metropolitan Health District in Santiago, Chile

-

ivThe Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH) and its Office of Transformative Global Health

-

vThe Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care for their support to CAMH

-

i

This study was also supported by the following:

Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), Doctoral Research Award.

The Transdisciplinary Understanding and Training on Research–Primary Health Care – TUTOR‐PHC – Fellowship funded by Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and Canadian Health Services Research Foundation (CHSRF)

Notes

For the purposes of this article, the term ‘mental health’ includes mental, alcohol‐ and substance‐use disorders.

This component of the study counted with the collaboration of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Nicaragua‐León.

Codes appear at the end of each quotation. The first three letters represent the country of the respondent (Chi = Chile, Mex = Mexico, Nic = Nicaragua). The type of method (Int = interview, FG = focus group, survey) and a number (not necessarily associated with the chronological order of the interviews in the country) for each respondent are also provided to help the reader to have a sense of the country of origin, research method and number, respectively. No more information is provided to protect anonymity and confidentiality of the participants.

Family and Community Health Model.

CAP = Centro de Atencion Psico‐Social (Centre of Psycho‐Social Care).

References

- 1. Kohn R, Levav I, Caldas de Almeida JM et al Los trastornos mentales en América Latina y el Caribe: asunto prioritario para la salud pública (Mental health disorders in Latin America and The Caribbean: a priority issue for public health). Revista Panamericana de Salud Publica, 2005; 18: 229–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Roses M. Renewing primary health care in the Americas: the Pan American Health Organization proposal for the twenty‐first century. Pan American Journal of Public Health, 2007; 21: 69–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rodríguez JJ. Mental health care systems in Latin America and the Caribbean. International Review of Psychiatry, 2010; 22: 317–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. WHO . Mental Health Action Plan 2013‐2020. Geneva: WHO, 2013. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/89966/1/9789241506021_eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 5. PAHO Strategy and Plan of Action on Mental Health for the Americas. 49th Directing Council CD49/11, PAHO, Washington, DC, USA, 28 September‐2 October 2009.

- 6. Gagné MA. What is Collaborative Mental Health Care? An Introduction to The Collaborative Mental Health Care Framework. Mississauga, ON: Canadian Collaborative Mental Health Initiative, 2005. Available at: http://www.ccmhi.ca/en/products/documents/02-Framework-EN.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 7. WHO, WONCA . Integrating Mental Health into Primary Care: A Global Perspective. Geneva: WHO, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 8. WHO . mhGAP Intervention Guide for Mental, Neurological and Substance Use Disorders in Non‐Specialized Health Settings, Mental Health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP). Geneva: WHO; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sapag JC, Rush B. Evaluation of primary care mental health In: Ivbijaro G. (editor in chief) Companion to Primary Care Mental Health. London: Radcliffe, 2012: 138–152. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hayes SL, Mann MK, Morgan FM, Kelly MJ, Weightman AL. Collaboration between local health and local government agencies for health improvement. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2012; 10. Art. No.: CD007825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stufflebeam DL, Shinkfield AJ. Evaluation Theory, Models, and Applications. San Francisco, USA: Jossey‐Bass, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Campbell NC, Murray E, Darbyshire J et al Designing and evaluating complex interventions to improve health care. BMJ, 2007; 334: 455–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. de Savigny D, Adam T. (eds). Systems Thinking for Health Systems Strengthening. Geneva: WHO, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 14. McLeod SK. Knowledge of need. International Journal of Philosophical Studies, 2012; 19: 211–230. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chen HT. The bottom‐up approach to integrative validity: a new perspective for program evaluation. Evaluation and Program Planning, 2010; 33: 205–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bryson JM, Patton MQ, Bowman RA. Working with evaluation stakeholders: a rationale, step‐wise approach and toolkit. Evaluation and Program Planning, 2011; 34: 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rush BR. Alternative models and measures for evaluating collaboration among substance use services with mental health, primary care and other services and sectors. Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 2014; 31: 27–44. [Google Scholar]

- 18. O'Sullivan R. Collaborative evaluation within a framework of stakeholder‐oriented evaluation approaches. Evaluation and Program Planning, 2012; 35: 518–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. McKillip J. Need Analysis: Tools for The Human Service and Education. Applied Social Research Methods Series. 10. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jiménez Villa J. Evaluation needs: The perspective of the population. Atencion Primaria, 2007; 39: 395–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. McKillip J. Needs analysis: Processes and techniques In: Bickman L, Rog DJ. (eds). Handbook of Applied Social Research Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1998: 261–284. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Adam T, Hsu J, de Savigny D, Lavis JN, Røttingen JA, Bennett S. Evaluating health systems strengthening interventions in low‐income and middle‐income countries: Are we asking the right questions? Health Policy and Planning, 2012; 27 (Suppl 4): iv9–iv19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ, 2008; 337: a1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL, Gutmann M, Hanson W. Advanced mixed methods research designs In: Tashakkori A, Teddlie C. (eds) Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social and Behavioral Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2003: 209–240. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ritchie J, Spencer L. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research In: Bryman A, Burgess RG. (eds) Analyzing Qualitative Data. London: Sage, 1994: 173–194. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Skinner HA. Promoting Health Through Organizational Change. San Francisco, CA: Benjamin Cummings, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Teddlie C, Tashakkori A. Major issues and controversies in the use of mixed methods in the social and behavioral sciences In: Tashakkori A, Teddlie C. (eds) Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social and Behavioral Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2003: 3–50. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 2nd edn Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Haggerty JL. Measurement of primary healthcare attributes from the patient perspective. Healthcare Policy, 2011; 7 (Special Issue): 13–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Aday A, Begley CH, Lairson DR, Balkrishnan R. Evaluating the Healthcare System: Effectiveness, Efficiency and Equity. Chicago: AHR, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Abel S, Marshall B, Riki D, Luscombe T. Evaluation of Tu Meke PHO's Wairua Tangata Programme: A primary mental health initiative for underserved communities. Journal of Primary Health Care, 2012; 4: 242–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Othieno C, Jenkins R, Okeyo S, Aruwa J, Wallcraft J, Jenkins B. Perspectives and concerns of clients at primary health care facilities involved in evaluation of a national mental health training programme for primary care in Kenya. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 2013; 7: 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. WHO . Mental Health Atlas 2011. Geneva: WHO, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 34. WHO . Mental Health Systems in Selected Low‐ and Middle‐Income Countries: A WHO‐AIMS Cross‐National Analysis. WHO: Geneva, 2009. Available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2009/9789241547741_eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shengelia B, Murray CJL, Adams OB. Beyond access and utilization: Defining and measuring health system coverage In: Murray CJL, Evans DB. (eds) Health Systems Performance Assessment: Debates, Methods, and Empiricism. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Trochim WM, Cabrera DA, Milstein B, et al Practical challenges of system thinking and modeling in Public Health. American Journal of Public Health, 2006; 96: 538–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bowling A. Research Methods in Health: Investigating Health and Health Services. New York, NY: Open University Press, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Somekh B, Lewin C. Theory and Methods in Social Research. London: Sage, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Doyal L, Gough I. A theory of human needs. Critical Social Policy, 1984; 4: 6–38. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cristofalo M, Boutain B, Schraufnagel TJ, Bumgardner K, Zatzick D, Roy‐Byrne PP. Unmet need for mental health and addictions care in urban community health clinics: Frontline provider accounts. Psychiatric Services, 2009; 60: 505–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K. (eds). Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. San Franciso: Jossey‐Bass, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sapag JC, Rush B, Barnsley J. Evaluation Dimensions for Collaborative Mental Health Services in Primary Care Systems in Latin America: Results of a Delphi Group. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2014; Jun 25. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43. Thornicroft G, Tansella M. The Mental Health Matrix. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Secretaria de Salud del Estado de Hidalgo . Diagnóstico de Salud del Estado de Hidalgo 2008 [Health Assessment of the State of Hidalgo]. Hidalgo: Secretaria de Salud del Estado de Hidalgo, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 45. SSMSO. (2010) . Cuenta Pública 2010, SSSMO [2010 SSMSO Public Report]. Santiago: SSMSO, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 46. SSMSO . Análisis de la red de salud mental del SSMSO [Analysis of the mental health network]. Santiago: SSMSO, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 47. SSMSO . Plan de Salud Mental 2011, SSMSO [2011 SSMSO Mental Health Plan]. Santiago: SSMSO, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 48. PAHO . Health in the Americas 2012. Washington, DC: PAHO, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 49. The World Bank . GINI Index. Available at: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.GINI, accessed 02 July 2013.

- 50. World Bank . World Bank Report 2010, 2010.

- 51. PAHO/WHO and Secretaria de Salud . WHO‐AIMS Country Report: Mexico, 2011.

- 52. WHO . WHO‐AIMS Country Report: Nicaragua, 2006.

- 53. WHO and Chilean Ministry of Health. WHO‐AIMS Country Report: Chile, 2007.

- 54. Secretaria de Salud . Modelo integrador de atención a la salud, Subsecretaría de Innovación y Calidad, Secretaría de Salud [Integrative model of health care, Sub‐Secretary of Innovation and Quality, Health Secretary], 2006. Available at: http://www.dgplades.salud.gob.mx/descargas/biblio/MIDAS.pdf, accessed 02 July 2013.

- 55. MINSA .Plan Nacional de Salud, Victoria, 2011. [National Health Plan, Victory, 2011].

- 56. Missoni E, Solimano G. Towards Universal Health Coverage: the Chilean Experience. World Health Report. Background Paper, No 4, 2010. Available at: http://www.who.int/healthsystems/topics/financing/healthreport/4Chile.pdf, accessed 02 July 2013.