Abstract

Background

This study aimed to analyse how immigrant workers in Spain experienced changes in their working and employment conditions brought about Spain's economic recession and the impact of these changes on their living conditions and health status.

Method

We conducted a grounded theory study. Data were obtained through six focus group discussions with immigrant workers (n = 44) from Colombia, Ecuador and Morocco, and two individual interviews with key informants from Romania living in Spain, selected by theoretical sample.

Results

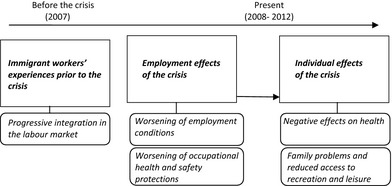

Three categories related to the crisis emerged – previous labour experiences, employment consequences and individual consequences – that show how immigrant workers in Spain (i) understand the change in employment and working conditions conditioned by their experiences in the period prior to the crisis, and (ii) experienced the deterioration in their quality of life and health as consequences of the worsening of employment and working conditions during times of economic recession.

Conclusion

The negative impact of the financial crisis on immigrant workers may increase their social vulnerability, potentially leading to the failure of their migratory project and a return to their home countries. Policy makers should take measures to minimize the negative impact of economic crisis on the occupational health of migrant workers in order to strengthen social protection and promote health and well‐being.

Keywords: Immigrant workers, economic recession, unemployment, health, occupational health, qualitative, grounded theory

Introduction

Starting in the late 1990s, Spain received a large influx of immigrants from various – primarily low‐income – countries due to the country's rapid economic growth and the demand for low‐skilled labour. The foreign‐born, economically active population rose from 2% of the general population in 1998 to 12.2% in 2010.1 However, in 2009, the Spanish economy entered a period of recession, which produced a contraction in the labour market and deterioration in employment and working conditions. This economic crisis has primarily affected the construction and services sectors, which accounted for 85% of immigrant employment in 2009. Unemployment in this group has increased with respect to native‐born workers (in 2010, the unemployment rate for native Spaniards was 18.2 vs. 30.2% for foreigners).1

Immigrant workers constitute a vulnerable population,2, 3, 4 and it has been shown that they are exposed to poor employment and working conditions.5, 6 In addition, it has been suggested that immigrant workers show poorer perceived general and mental health3, 7 and higher frequency of work‐related health problems when compared to native workers.8, 9, 10

Through unemployment, job insecurity and declining household incomes, economic crises can have negative effects on health.11, 12 To date, research on the effect of periods of economic crisis on health has been limited, and studies in Spain have focused primarily on the general population13, 14 and primary care patients.15 Studies carried out in other countries during times of economic recession have shown an increase in health problems,16, 17 above all in terms of mental health,18 in addition to an increase in mortality due to suicide.19, 20 Employment uncertainty is a consequence of processes of business restructuring and lay‐offs and has an impact on the health of not only those employees who lose their jobs, but also those who continue working,21 which is related to psychosocial factors.22 Among this former group, an increase in episodes related to anxiety and depression has been observed related to workers' uncertainty about their future, increased conflicts between employees, and increased workloads related to reductions in personnel.23 Therefore, the question of how the crisis is affecting specific groups such as immigrant workers is important.

‘Immigration, Work and Health' (Spanish acronym, ITSAL) is an on‐going research project in Spain involving the collaboration of several occupational health research groups. The general objective of the project is to analyse employment and working conditions among immigrant workers and their relationship to health using different methodologies.24, 25 The project results obtained to date indicate that immigrant workers have experienced an increase in mental health problems since the onset of the crisis, compared with their situation when they arrived in Spain.26, 27 Certain groups and nationalities were affected in particular. Within the framework of this ITSAL project, the aim of this study was to analyse how immigrant workers in Spain experienced the changes in their working and employment conditions brought about by the economic recession, and the impact of these changes had on their living conditions and health status.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

A qualitative study was performed using six focus group discussions (FGD) and two semi‐structured individual interviews, conducted by the same moderator/interviewer. The technique of FGD was chosen considering (i) the importance of interaction and dialogue among participants in achieving a collective discourse, (ii) the possibility to encourage multiple discourses and elicit distinct opinions on the same subject, leading the participants to understand the differences and similarities of their experiences and (iii) the need to identify group norms.28 Three FGDs were held with men and three with women; each group involved 7–8 participants of the same sex and nationality (total n = 44 immigrants). We chose gender separated FGDs based on the assumption that participants share similar labour contexts that can better contribute to informing our research question. We wanted to explore the experiences in the labour market separately by sex because, in Spain, jobs for migrants are highly segregated by sex (domestic service for women and construction for men). Performing gender‐specific FGDs allowed us to gain a deeper understanding of the specific difficulties and consequences for men and women during periods of economic recession. The two interviews were held with key informants working for Romanian immigrant associations based in Spain.

The sample design for the FGDs was theoretical, meaning that a variety of participants were selected who could provide insights from different perspectives about the research question. The following characteristics were considered as inclusion criteria of participants in the FGDs: (i) a history of working in Spain and residence permits; (ii) belonging to a nationality with a substantial presence in Spain (Colombian, Ecuadorian and Moroccan); (iii) length of residency in Spain of 5 years, to obtain experiences before and after the crisis and (iv) ability to understand and communicate in Spanish. Both employed and unemployed people were included in the study. At minimum, all participants had a history of working in Spain and had residence permits. A general demographic overview of the participants is presented in Table 1. The key informants for the study (one man and one woman) were the presidents of two different Romanian Associations in Spain.

Table 1.

Socio‐demographic characteristics of participants in focus group discussions

| Characteristics | Females | Males | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean, range) | 39.7 (31–51) | 44.3 (33–52) | 41.8 (31–52) |

| Time in Spain (mean, range) | 9.7 (4–15) | 10.1 (5–17) | 9.9 (4–17) |

| Country of origin (n) | |||

| Colombia | 7 | 8 | 15 |

| Ecuador | 8 | 7 | 15 |

| Morocco | 7 | 7 | 14 |

| Employment status (n) | |||

| Employed | 7 | 11 | 18 |

| Unemployed | 15 | 11 | 26 |

| Education level | |||

| ≤Primary | 9 | 4 | 13 |

| Secondary | 9 | 9 | 18 |

| University | 3 | 7 | 10 |

| Total | 22 | 22 | 44 |

Missing value (education level: n = 3, legal status: n = 2).

Data collection

Fieldwork took place in Madrid between February and March of 2012. The first strategy used to recruit participants was to contact people working in immigrant associations, who facilitated contact with immigrants visiting these organizations. Second, participants were recruited through the snowballing technique, in which an initial participant indicates other possible participants. This technique is widely used in the study of hard‐to‐reach or socially isolated populations.29 The research team produced a guide for use in the FGDs that indicated a series of topics to be discussed among participants. This guide explored their employment history since arriving in Spain, changes in working and employment conditions due to the economic crisis and the influence of these changes on their health status and living conditions. Interviews and FGDs lasted between 90 and 120 min and were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. FGDs were performed until data saturation was reached, meaning that no new information emerged.30

Data analysis

Transcribed data were imported into the qualitative analysis software Atlas.Ti 5.2 for grounded theory analysis following Charmaz.31 Categories were identified from the data as follows: (i) in the text, sentences with the same meaning were identified; (ii) these were labelled with emerging codes – concepts summarizing the information; (iii) codes were then grouped into categories according to the theories of working and employment conditions and their effects on health and migration – in this step, we integrated theory with the emerging data; (iv) a conceptual model was formulated to relate participants' perceptions of the impact of the economic crisis on working and employment conditions, and health status.

Data analysis was conducted using Atlas.Ti and was conducted independently by three of the authors (EB, TG and AA), who examined and compared their analyses. The quotes given in the results section were chosen for their representativeness and selected following joint discussion.

Ethics

The study protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee at the University of Alicante. Participation in the study was voluntary, all respondents gave written informed consent to participate in the study, and confidentiality was guaranteed throughout the research process in accordance with Spanish regulations. Participants in the FDGs received a modest economic stipend for their participation.

Results

Three categories emerged from the analysis of the data collected in FDGs and interviews. From the relationship between these emerging categories, a conceptual model was developed showing a time‐causal process, from times of economic expansion to financial crisis that has taken place over recent years (Fig. 1). It illustrates the negative impact of the financial crisis – which worsened working and employment conditions – on their living conditions and health status. The conceptual model helps to understand how immigrant workers in Spain experienced (i) the structural consequences of the crisis as conditioned by their experiences in the period prior to the crisis, and (ii) the deterioration of their quality of life and health as consequences of the worsening of employment and working conditions due to the crisis.

Figure 1.

Theoretical model of how changes in working and employment conditions brought about by the financial crisis impact immigrants' health.

Immigrant workers' experiences prior to the crisis: progressive integration in the labour market

Entry into the Spanish labour market was not easy for immigrants. All the participants mentioned initial difficulties with employment in Spain, with the exception of those who arrived with better training, better contacts and/or previously arranged contracts, most had to accept worse jobs than those they had held in their country of origin. However, they also said that when they arrived, there were many employment opportunities and work was easy to find, even for those without the necessary permits, which in turn helped them to regularize their immigrant status in Spain. For example:

I arrived and I was like fifteen days without work, after fifteen days I found an undeclared job, in electricity, and then stayed with that company for ten years. Later I got my work permit there and stuff. (FGD Colombian men)

The occupational improvement was not usually associated with progress in terms of professional career, but rather with a considerable increase in salaries for construction workers (men) and domestic service workers and/or those providing elderly care (women). This period of job status improvement did not involve a generalized consolidation of employment within companies, such as the regularization of contracts; instead, some immigrants created small businesses with several self‐employed workers in the construction or service (hotel and catering) sectors (men), whilst others obtained contracts in the domestic service sector (women).

I started working in bars, cafeterias. Then I ran my own cafeteria until I ran smack into the crisis, so I kept my cafeteria for two years and I just closed it in September last year, in 2011. (FGD Moroccan men)

Employment consequences of the crisis

Worsening of working conditions

Participants in the study clearly experienced a reduction in employment opportunities brought about by the crisis.

Normally those who've kept their jobs are being paid less and are working more hours. (Personal Interview 1, Key informants, Romanian associations)

Men were more affected by unemployment, as there was less reduction in domestic service work. Female workers would then compensate for their partners' lack of income.

There's more work for women, and husbands… in my case for example, the company my husband worked for shut down and he's unemployed. (FGD Ecuadorian women)

However, there was a widespread drop in income among those who kept their employment, not only due to lower wages but also as a result of the reduced amount of work (particularly among the self‐employed) and/or number of hours (especially among women and in the domestic service/elder care sector).

Conditions have changed or gotten worse, I think so, because at the beginning for example I found work at ten Euros per hour/…/Yes, things have gotten really worse/…/The problem is that wages are still falling. (FGD Moroccan women)

Many immigrants felt that employers had taken advantage of the crisis and the growing pool of people willing to work for less money as an excuse to lower wages. A more competitive labour market was especially noticeable for self‐employed workers.

The worst thing is the competition, there's very unfair competition around at the moment between…, in a job now for example, you quote one thousand Euros for example, and now they say, no, look, I can give you five hundred or four hundred because there's really strong competition./…/There are other blokes out there who are doing it are cheaper and so obviously, they're taking our work. (FGD Colombian men)

Among those who were still employed, employment conditions changed and became more temporary, with contracts typically lasting 2–3 months or becoming contracts for the supply of services, and some contracts even disappeared.

It's much worse because they don't have to sack you, they just say don't come back tomorrow. (Personal Interview 1, Key informants, Romanian associations)

This situation was problematic for some of them, making it more difficult to keep their residence and/or work permits in Spain.

Some people have lost them [residence/work permits] precisely because of lack of work/…/without a permit they don't register you with the social security, and if you do find work, you haven't got a permit and you can get into real trouble, so it's just awful. (FGD Colombian women)

Although the number of working hours decreased, they were required to carry out the same work, leading to the perception of labour abuse.

You work more, what they do is they lay off staff and give you more work to do/…/If before we went to the house two or three times a week, now we only go once. And because it's only once, there's more work to do. (FGD Colombian women)

Reduced occupational health and safety protection

Workers indicated that the crisis had a significant and negative effect on business investment in health and safety measures.

They do not give you all the tools now or protection, before they gave you from a pin to the most expert machine in the world, everything necessary, but now you have to have your tools, everything, and everything. So yes, it has reduced. (FGD Colombian men)

Immigrants perceived their possibilities to influence their labour conditions as very limited, or even non‐existent and, due to fear of unemployment, participants accepted whatever jobs were offered regardless of the conditions.

We all know what's out there, and so you're scared, if you've got something you hang onto it, you put up with it and carry on. (FGD Moroccan women)

Employees were advised to refrain from performing potentially hazardous tasks, although immigrant workers feel that this was more intended to avoid the possible negative consequences for employers than to protect employees. Furthermore, if an accident did occur in the house, employees might claim that it had happened outside to shield the employer from economic penalties.

The glass from the window. You took the small panes out to clean them. Now they insist that you mustn't do it, why? Because the company washes its hands if you have an accident, they're really not going to compensate you for…, so there are a number of things that you can't do in some houses/…/it's to avoid accidents, so that if someone does something stupid and has an accident then it's their own fault, not the fault of the company, so they give you everything in writing. (FGD Colombian women)

Individual consequences of the crisis

Negative effects on health

Participants experienced deterioration in their quality of life that they attributed to the worsening of working conditions. They reported suffering from stress and depression, which they interpreted as consequence of worries about unemployment and economic problems (lower income and debts).

And health as well, because of the stress, because you're thinking about your debts, about not having enough money, that you need to do more work, in the end, all that stress chips away at your health/…/What with his illness and the girls, my husband's becoming seriously depressed and I have to cope with that as well. (FGD Colombian women)

Participants felt frustrated because of the limited possibilities for improving the situation, and the dream of a better life in Spain was replaced by the possibility of having to relocate or returning to the country of origin.

The crisis has also affected us psychologically, because we had dreams, and they're not happening and so then you start to ask, what am I doing here? (FGD Colombian men)

The pressure and distress experienced by immigrants are perceived as impacting their physical health, and they report symptoms as diffuse pain – especially muscle pain – headaches and gastric discomfort. Taking medication to sleep better is a common mechanism for coping with the situation.

The migraines I get now/…/When I'm under pressure, I don't sleep at night, I don't sleep well, sometimes I go to the A&E when I'm in a lot of pain until they give me some Voltaren, they inject me to stop the pain, it's because of unemployment. I can see unemployment coming/…/I can't stop worrying about it, and when I'm really worried/…/I start getting pains all over, in my neck, my shoulders and then I go to see my doctor he gives me some pills to sleep, but even with these I can't sleep. (FGD Moroccan women)

Worsening of dietary habits in response to a reduced income, related to reducing quantity and quality of foods, was common among immigrant workers.

You can only save on food, because you can't stop paying the bills, but you start eating a little less, or stop eating the same quality of food as before, you start to reduce it. (FGD Colombian women)

For some, the crisis led to extreme situations such as asking for food in churches and resorting to charity.

You're worried, thinking all day long about what to do for food today/…/I've been to lots of places, to churches to ask for food for my daughter and me. (FGD Colombian women)

Effects on family relationships and reduced access to recreation and leisure

Immigrants felt that their family life had been negatively affected by the crisis. Women were unhappy seeing their partners unemployed, and this situation led to women's worry about their husbands and shame on the part of the men, who could no longer support the family.

People whose partners don't have work permits, imagine it, if you send them to look for work, you're sending them directly to Colombia, and seeing them at home is stressful for you, you get sick, they get sick and it's super complicated right now dealing with the crisis. (FGD Colombian women)

Difficulties emerged between couples due to family tensions occasioned by economic problems, resulting in marital crisis and problems in their sexual life, sometimes even leading to the breakdown of relationships.

The burden becomes too heavy to handle such that relationship breaks up. I think we break up because a lack of sexual appetite…, you are always with bad humour as the partner is continuously under your feet… (FGD Colombian women)

Immigrants had fewer possibilities to participate in leisure activities with family members, such as travelling or going on family outings, which, in their opinion, was caused by the reduction in wages brought about by the economic recession. This also led to frustration because of the effect on children, who also perceived changes in their quality of life.

And you notice it in the home, in the family, in the children, because before, you said this weekend I'm going to take you to such and such a place, but now, this weekend we won't be going out because there isn't any money. And a child is a child and they also notice it/…/ (FGD Colombian men)

Worries about economic dependants in their countries of origin also provoked personal crises in immigrants' family relationships. Workers felt frustrated and helpless about not having enough money to support these dependents, or because of the difficulty in returning to their country of origin to see them. The main objective of economic migrants is to improve employment opportunities and the financial situation, but the crisis has resulted in the loss of employment and resources needed to support the family. This made it difficult for immigrants to offer their children educational and financial resources, symbolizing ‘the failure of a life project'.

Before I could help my parents, who live in Ecuador, I sent them some help, but now I can't send them money… It makes me a little worried and ashamed. That's what ‘s happened to me with this crisis. (FGD Ecuadorian men)

Discussion

The results of this study help construct a conceptual model that shows an increase in the vulnerability of immigrant workers during the economic crisis in Spain from both an employment and a personal perspective. Their status as unskilled workers in sectors hard‐hit by the recession, with temporary contracts or no contract at all, and the deterioration in working and employment conditions during the crisis, has placed them in a situation of great instability. The results show that immigrants attributed negative consequences for their health and quality of life to the crisis as consequence of the unemployment and worsening of employment conditions. Immigrant workers felt deterioration in their health, in terms of mental health, poor sleep and associated physical symptoms, as a result of worries and concerns. Feelings of failure about their migratory project and the desire to return to their countries could be understood in the time‐line process (Fig. 1) as consequence of the worsening of their quality of life due to the crisis.

During periods of economic crisis, there is an increase in the proportion of citizens experiencing social and economic vulnerability, for example those with greater exposure to different risks related to certain shared social characteristics, such as weak social ties and precariousness in labour insertion. There is an increase in the proportion of population groups that are susceptible to a worsening of quality of life, due to their prior experience of precarious conditions or due to being employed in the sectors most affected by the recession. The results of the present study reflect that immigrant workers are among this group.

It is important to mention Spanish policies that affected immigrants at the time of the study. Immigrants who were documented (affiliated with Social Security) had the same rights as Spanish workers in terms of health services (free at all levels of care) and social assistance (including unemployment and disability). They also had the same obligations in terms of payment of taxes and contributions to Social Security. However, a significant number of immigrants worked without affiliation with Social Security, and they did not have access to unemployment benefits. Prior to the economic crisis, being registered with a local residence granted free access to health services, although this policy changed at the end of 2012 when the government passed urgent measures to guarantee the sustainability of the health system during the time of crisis.

The association between health and employment made by participants coincides with findings from other studies of the general population. For example, perceived job insecurity has been suggested as a significant predictor of poorer self‐rated health and depressive symptoms.32 Furthermore, Modreck and Cullen reported high work‐related stress in salaried workers at plants with high rates of lay‐offs compared with their counterparts at non‐high lay‐off plants.23 A reduced income and difficulties meeting needs have been linked to poorer mental and general health.33 Our results also show that the new economic context can obligate women to increase the number of hours they work in order to increase their earnings, as they often become the sole source of income for the family. Numerous literature reviews have examined the health effects of long working hours,34, 35 which have been positively associated with adverse health outcomes including poor general health,36 cardiovascular disease,37 musculoskeletal disorders,38 work‐related injuries,39 depression40, 41, 42 and sleep disruption.43

Our results build upon previous theory about immigration and occupational health. The results highlight three conditions that emerge as risk factors specifically associated with immigration, in contrast with the native population. The first condition is the lack of social and family support in Spain in times of real need. The second condition is the presence of dependents in the country of origin; a lack of income precludes both sending money and communicating via telephone due to the cost. The third condition is having to face the sense of personal failure regarding the migratory project, understood as the feeling of hopelessness and frustration that arises when an immigrant fails to ensure even the slightest possibility of paying for a trip back to the country of origin. Despite the fact that the health needs of immigrants are comparable to those of the local population and that they often enjoy a better state of health than locals at the time of their arrival, the immigrant population generally tends to be more vulnerable to development of a poor state of health. This is due in part to their greater exposure to social determinants of poor health such as lower incomes and precarious living and working conditions.

Our study also highlights how health – in particular mental health and associated physical symptoms – is affected by situations of economic crisis. Health problems that are typical of the immigrant syndrome with chronic and multiple stress (Ulysses Syndrome) emerged, such as depression (primarily sadness and tears), anxiety (stress, insomnia, recurrent intrusive thoughts, irritability) and somatic disorders (fatigue, musculoskeletal pain, headaches, gastric discomfort).44

This study also revealed that the situation affects men and women differently. One study of the immigrant population in Spain26 showed that between 2008 and 2011, the prevalence of poor mental health among employed immigrants increased by 20% in women and 75% in men. Our results indicate that men experience frustration and depression as a result of being unable to exercise the role of breadwinner for their families, with repercussions for their relationships. These findings are in line with other studies, which have shown that loss of the breadwinner role changes both gender and family roles and responsibilities, increasing problems between the couple.45 Our results suggest that in the dual breadwinner family models that characterize immigrant couples, the crisis has forced a shift towards a model in which women are the new family breadwinners. However, this is not accompanied by a reduction in gender inequality, but rather entails additional burdens for women, who must cope with long working hours and a deterioration in their health status.46

Whilst this analysis helps provide an in‐depth understanding of the situation faced by immigrant workers during the economic recession in Spain, there are some limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the findings should not be considered representative of the whole population of immigrant workers in Spain, because the generalizability of the study findings is limited due to the nature of qualitative research. Despite this, the results make theoretical contributions about the possible impact of the economic crisis on the working conditions and health outcomes of a large number of immigrants. The possibility of informing other research about immigrants is based on the fact that (i) we contextualized the results to enable readers to evaluate the extent to which our results might be applicable to other, similar settings; and (ii) cases were chosen following a theoretical sample design, which permitted taking the information from culturally, geographically and socially diverse groups (South American vs. Morocco as the groups most representative of immigrants in Spain) that offer different perspectives of reality. Also, this study does not reflect the experiences of other, less represented immigrant groups in Spain, such as the Asian population or those from eastern European countries other than Romania, which were not considered according to the inclusion criteria applied in this study.

Despite these limitations, one of the study's main strengths was the use of information provided by a hard‐to‐reach population. We established the trustworthiness of this qualitative study through theoretical sampling, credibility through triangulation of researchers and participants, through involving different worker profiles; and dependability using an emergent design.47 As a further step, in future studies, it would be interesting to include other migrant groups and/or to mix women and men in the FGs to compare their views regarding family consequences of periods of economic crisis. More in‐depth research should be conducted that includes interviewing participants individually to better understand specific questions arising from the current study (such as the evolution of the economic recession and labour market contraction and the consequences of this phenomenon over the mid‐ and long‐term).

These findings indicate the importance of a concerted focus on the needs of immigrant workers during difficult economic times. Policy makers should be aware that immigrant groups are hit hard by reductions in their social protections as they already experience lower levels of financial and social capital than natives. Further research and policy initiatives should focus on strengthening mechanisms that would allow immigrant groups to better weather times of economic crisis.

In conclusion, immigrant workers in Spain reported deterioration in their employment situation and working conditions since the onset of the economic recession in the country, and they felt that this situation has led to emotional distress and poor sleep, diminishing their quality of life and self‐perceived health status. An additional consequence of the crisis for these individuals may be feelings of failure about their migratory project and the desire to return to their countries.

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interests has been declared.

Source of funding

This study was funded by the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (FIS PI11/01192) and the University of Alicante.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the participants for sharing their experiences with us.

References

- 1. Spanish National Statistics Institute . Municipal Register of Inhabitants. Madrid: Spanish National Statistics Institute, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schenker MB. A global perspective of migration and occupational health. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 2010; 53: 329–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Porthe V, Benavides FG, Vazquez ML et al Precarious employment in undocumented immigrants in Spain and its relationship with health. Gaceta Sanitaria, 2009; 23(Suppl. 1): 107–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Agudelo‐Suarez AA, Ronda‐Perez E, Gil‐Gonzalez D et al The effect of perceived discrimination on the health of immigrant workers in Spain. BMC Public Health, 2011; 11: 652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Benach J, Muntaner C, Delclos C, Menendez M, Ronquillo C. Migration and “low‐skilled” workers in destination countries. PLoS Medicine, 2011; 8: e1001043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ronda PE, Benavides FG, Levecque K, Love JG, Felt E, Van Rossem R. Differences in working conditions and employment arrangements among migrant and non‐migrant workers in Europe. Ethnicity & Health, 2012; 17: 563–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ahonen EQ, Lopez‐Jacob MJ, Vazquez ML et al Invisible work, unseen hazards: the health of women immigrant household service workers in Spain. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 2010; 53: 405–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ahonen EQ, Benavides FG, Benach J. Immigrant populations, work and health–a systematic literature review. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 2007; 33: 96–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jolivet A, Cadot E, Florence S, Lesieur S, Lebas J, Chauvin P. Migrant health in French Guiana: are undocumented immigrants more vulnerable? BMC Public Health, 2012; 12: 53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sousa E, Agudelo‐Suarez A, Benavides FG et al Immigration, work and health in Spain: the influence of legal status and employment contract on reported health indicators. International Journal of Public Health, 2010; 55: 443–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stuckler D, Basu S, Suhrcke M, McKee M. The health implications of financial crisis: a review of the evidence. Ulster Medical Journal, 2009; 78: 142–145. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Suhrcke M, Stuckler D. Will the recession be bad for our health? It depends. Social Science & Medicine, 2012; 74: 647–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bartoll X, Palencia L, Malmusi D, Suhrcke M, Borrell C. The evolution of mental health in Spain during the economic crisis. European Journal of Public Health, 2013; 24: 415–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Regidor E, Barrio G, Bravo MJ, de la Fuente L. Has health in Spain been declining since the economic crisis? Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 2014; 68: 280–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gili M, Roca M, Basu S, McKee M, Stuckler D. The mental health risks of economic crisis in Spain: evidence from primary care centres, 2006 and 2010. The European Journal of Public Health, 2013; 23: 103–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Catalano R, Goldman‐Mellor S, Saxton K et al The health effects of economic decline. Annual Review of Public Health, 2011; 32: 431–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kentikelenis A, Karanikolos M, Papanicolas I, Basu S, McKee M, Stuckler D. Health effects of financial crisis: omens of a Greek tragedy. Lancet, 2011; 378: 1457–1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wang J, Smailes E, Sareen J, Fick GH, Schmitz N, Patten SB. The prevalence of mental disorders in the working population over the period of global economic crisis. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 2010; 55: 598–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Norström T, Grönqvist H. The Great Recession, unemployment and suicide. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 2015; 69: 110–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Economou M, Madianos M, Theleritis C, Peppou LE, Stefanis CN. Increased suicidality amid economic crisis in Greece. Lancet, 2011; 378: 1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Janlert U. Unemployment as a disease and diseases of the unemployed. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 1997; 23(Suppl. 3): 79–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Houdmont J, Kerr R, Addley K. Psychosocial factors and economic recession: the Stormont Study. Occupational Medicine, 2012; 62: 98–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Modrek S, Cullen MR. Job insecurity during recessions: effects on survivors' work stress. BMC Public Health, 2013; 13: 929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Delclos CE, Benavides FG, Garcia AM, Lopez‐Jacob MJ, Ronda E. From questionnaire to database: field work experience in the ‘Immigration, work and health survey' (ITSAL Project). Gaceta Sanitaria, 2011; 25: 419–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Garcia AM, Lopez‐Jacob MJ, Agudelo‐Suarez AA et al [Occupational health of immigrant workers in Spain [ITSAL Project]: key informants survey]. Gaceta Sanitaria, 2009; 23: 91–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Agudelo‐Suarez AA, Ronda E, Vazquez‐Navarrete ML, Garcia AM, Martinez JM, Benavides FG. Impact of economic crisis on mental health of migrant workers: what happened with migrants who came to Spain to work? International Journal of Public Health, 2013; 58: 627–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Robert G, Martinez JM, Garcia AM, Benavides FG, Ronda E. From the boom to the crisis: changes in employment conditions of immigrants in Spain and their effects on mental health. European Journal of Public Health, 2014; 24: 404–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kitzinger J. Qualitative research. Introducing focus groups. British Medical Journal, 1995; 311: 299–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Faugier J, Sargeant M. Sampling hard to reach populations. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 1997; 26: 790–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Patton MQ. Qualitative evaluation methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage publications Inc., 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Charmaz K. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis, 1st edn London, Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Burgard SA, Brand JE, House JS. Perceived job insecurity and worker health in the United States. Social Science and Medicine, 2009; 69: 777–785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Martikainen P, Adda J, Ferrie JE, Smith GD, Marmot M. Effects of income and wealth on GHQ depression and poor self rated health in white collar women and men in the Whitehall II study. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 2003; 57: 718–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bannai A, Tamakoshi A. The association between long working hours and health: a systematic review of epidemiological evidence. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 2014; 40: 5–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Spurgeon A, Harrington JM, Cooper CL. Health and safety problems associated with long working hours: a review of the current position. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 1997; 54: 367–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ettner SL, Grzywacz JG. Workers' perceptions of how jobs affect health: a social ecological perspective. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 2001; 6: 101–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Virtanen M, Heikkila K, Jokela M et al Long working hours and coronary heart disease: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. American Journal of Epidemiology, 2012; 176: 586–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lipscomb JA, Trinkoff AM, Geiger‐Brown J, Brady B. Work‐schedule characteristics and reported musculoskeletal disorders of registered nurses. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 2002; 28: 394–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Simpson CL, Severson RK. Risk of injury in African American hospital workers. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 2000; 42: 1035–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hilton MF, Whiteford HA, Sheridan JS et al The prevalence of psychological distress in employees and associated occupational risk factors. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 2008; 50: 746–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hovey JD, Magana C. Acculturative stress, anxiety, and depression among Mexican immigrant farmworkers in the midwest United States. Journal of Immigrant Health, 2000; 2: 119–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Park SY, Bernstein KS. Depression and Korean American immigrants. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 2008; 22: 12–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kivisto M, Harma M, Sallinen M, Kalimo R. Work‐related factors, sleep debt and insomnia in IT professionals. Occupational Medicine, 2008; 58: 138–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Achotegui J. Emigration in hard conditions: the Immigrant Syndrome with chronic and multiple stress (Ulysses' Syndrome). Vertex, 2005; 16: 105–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Fisher C. Changed and changing gender and family roles and domestic violence in African refugee background communities post‐settlement in Perth, Australia. Violence Against Women, 2013; 19: 833–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Artazcoz L, Cortes I, Escriba‐Aguir V, Bartoll X, Basart H, Borrell C. Long working hours and health status among employees in Europe: between‐country differences. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 2013; 39: 369–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Guba EG, Lincoln YS. Competing paradigms in qualitative research. Handbook of Qualitative Research, 1994; 2: 163–194. [Google Scholar]