Abstract

Background

Governments in several countries are facing problems concerning the accountability of regulators in health care. Questions have been raised about how patients' complaints should be valued in the regulatory process. However, it is not known what patients who made complaints expect to achieve in the process of health‐care quality regulation.

Objective

To assess expectations and experiences of patients who complained to the regulator.

Design

Interviews were conducted with 11 people, and a questionnaire was submitted to 343 people who complained to the Dutch Health‐care Inspectorate. The Inspectorate handled 92 of those complaints. This decision was based on the idea that the Inspectorate should only deal with complaints that relate to ‘structural and severe’ problems.

Results

The response rate was 54%. Self‐reported severity of physical injury of complaints that were not handled was significantly lower than of complaints that were. Most respondents felt that their complaint indicated a structural and severe problem that the Inspectorate should act upon. The desire for penalties or personal satisfaction played a lesser role. Only a minority felt that their complaint had led to improvements in health‐care quality.

Conclusions

Patients and the regulator share a common goal: improving health‐care quality. However, patients' perceptions of the complaints' relevance differ from the regulator's perceptions. Regulators should favour more responsive approaches, going beyond assessing against exclusively clinical standards to identify the range of social problems associated with complaints about health care. Long‐term learning commitment through public participation mechanisms can enhance accountability and improve the detection of problems in health care.

Keywords: complaints, government regulation, health‐care quality, health‐care safety, public participation

Introduction

In a number of countries, high‐profile incidents in health care have led to critical re‐examinations of the roles of regulators. Governments are facing problems concerning organizational failures, public confidence in regulators and accountability of regulators.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 One widely discussed incident is the Mid Staffordshire Trust hospital scandal in the UK. In this case, several regulatory agencies including the government failed to respond to various emerging signals including patient complaints. Major lapses in health‐care quality remained unnoticed, and mortality rates increased between 2005 and 2009 due to appalling care.3, 4 It was concluded that ‘complaints were not given a high enough priority in identifying issues and learning lessons’.4 The approach taken by the regulator gave the appearance of looking for reasons for not taking action rather than acting in the public interest. Public confidence in the regulator and the health‐care system could therefore not be maintained.4, 8 Other countries such as New Zealand, the USA and the Netherlands are facing similar problems with public confidence, and it has become more important that there should be reform in safety cultures that deal with public demands for greater accountability from health services and regulators.5, 9, 10 Furthermore, political attention for the use of information from patients, including complaints, and improving public participation in regulatory processes has increased.6, 8, 11, 12 This development can be seen in the way that increased attention is now being paid to reinforcing patient's positions in health care.13

Complaints by patients in general and utilization of such complaints for regulating health‐care quality are much debated topics in many countries. However, we were concerned to note that no research has been performed on what patients with complaints expect from a regulator. This article therefore aimed to seek an answer to the following questions, using the Dutch situation as a case study:1

What is the subject and nature of complaints submitted by patients to the Dutch Health‐care Inspectorate?

How do patients with complaints rate the severity of the physical harm that has been carried out? And are differences observed between patients whose complaints were and were not handled by the Inspectorate?

What outcome do patients who submitted complaints to the Inspectorate expect from the complaint handling, and are there differences between the aforementioned groups (handled and not handled)?

Are those expectations met?

The following sections address the theoretical concepts underlying regulation policies, current policies in the Netherlands regarding complaints about regulatory processes, followed by the Methods, Results, Discussion and Conclusions.

Theoretical framework: regulation, public participation and complaints

Internationally, the ‘responsive regulation’ theory of Ayres and Braithwaite (1992) is the basis for regulation policies in various industries such as finance, environmental businesses and health care. This theory assumes that the relationship between the regulator and regulated parties is based on co‐operation and trust. Regulation based on distrust would only lead to more penalties being imposed and therefore requires more capacity on the part of the regulator and ultimately leads to higher societal costs. Regulatory compliance is encouraged firstly by using more lightweight measures such as persuasion and secondly by applying more weighty measures in the case of riskier behaviour by the regulated parties. This principle is also known as ‘the stick or the carrot’.14 Another important element of the theory is ‘tripartism’, whereby a third group such as patients or consumers is involved in the regulatory process. This is proposed as an approach for empowering public interest groups by giving them a voice and letting them participate. This ought also to enhance the legitimacy and accountability of a regulator. Furthermore, it could prevent regulatory capture and value conflicts between different stakeholders.1, 14, 15, 16, 17 The use of patients' complaints for regulatory purposes can be considered as a form of tripartism in which the services learn from their users. Research has already shown that complaints can add value to regular regulatory monitoring systems.18, 19, 20

When comparing different complaints procedures with different goals such as individual complainant satisfaction or disciplinary complaint procedures, complainants seem rather unanimous in what they expect of the procedures. For most people, it is important that their sense of justice is restored and that the problem is prevented from recurring.21, 22, 23, 24 However, the majority of complainants believe that no changes are made in response to their complaint.21, 22, 25

Complaints in the Dutch regulatory system

Internationally, changing political views on approaches to governance and regulation have resulted in shifts from centralized to decentralized systems, with governmental authorities retreating and leaving responsibility to those in the field.2, 13, 26 In the Netherlands, those changing views resulted in the adoption of the Quality Act in 1996, placing responsibility for health‐care quality primarily with care providers. This responsibility also includes handling individual complaints from patients about health care. The Dutch Health‐care Inspectorate is an independent part of the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sports and is mandated to supervise and regulate health‐care quality. The Inspectorate supervises compliance with obligations imposed by legislation, assuming that care providers have an intrinsic motivation to act rationally and socially responsibly, according to the theory of responsive regulation.14 It is possible for patients to register complaints about health care with the Inspectorate. The statutory tasks of the Inspectorate do not let it give individual judgments about complaints. Instead, it uses complaints for general risk analyses. Complaints are only eligible for handling by the Inspectorate and further investigation when complaints meet the following specific criteria: severe deviation from the applicable professional standards by professional or other employees within the institution, severe failure or the absence of an internal quality system at an institution, severe harm to health or a high probability of recurrence of the problem.27 If the complaint meets one of the criteria, the Inspectorate firstly entrusts the care provider in question to investigate the problem, which is in line with the theory of responsive regulation. If necessary, the Inspectorate starts its own investigation. If the complaint does not meet any of the criteria, the Inspectorate must ensure that the complainant receives information about other options for obtaining a judgment.27, 28

The Inspectorate receives approximately 1400 complaints by patients each year of which the majority are not handled by the Inspectorate, given its statutory task.28 However, as in the UK, it was argued that the Inspectorate does not take patients and their complaints seriously and does not value patients' complaints as signalling deeper problems.3, 4, 29, 30, 31 It was stated in political debates and by the Dutch ombudsman that the patients and their complaints deserve more attention and should be involved in regulation policies to reflect patients' needs.29, 30, 31 Previous research demonstrated that the Dutch general public also agreed that patients' complaints should be an important source of information for regulation of health‐care quality (R. Bouwman, M. Bomhoff, J.D. De Jong, P.B. Robben, R. Friele, unpublished data, submitted).

Methods

In this study, existing questionnaires developed in previous studies among complainants at complaint boards and disciplinary boards were used to develop a new questionnaire. Interviews were conducted with complainants at the Inspectorate to examine whether those questionnaires were applicable to this target group.

Development of the questionnaire

The questionnaire that was developed was mainly based upon questionnaires used in previous research about expectations and experiences of complainants in health care (to complaint boards and disciplinary boards).32, 33, 34 The design of those questionnaires was driven by the theory of procedural, distributive and interactional justice.35 Information from the interviews was used to adjust the questionnaire specifically to the characteristics of the regulator. Interviews were conducted with people who had made a complaint to the Inspectorate to identify whether the questionnaires would also apply to this setting. The Inspectorate contacted a sample of 25 people with complaints about a wide variety of health‐care sectors, who could then voluntarily sign up for the interviews with the first author. Eleven people signed up. During five interviews, a second interviewee participated. In total, nine males and seven females were interviewed. Subjects of the complaints were hospital care, ambulance services, mental health care, pharmacy, care for disabled and nursing homes. Respondents could indicate their preference for the interview location. Most chose to be interviewed at their home. Three interviews were conducted by telephone. The interview consisted of open questions using a topic list. Questions were focused on the complaint itself, the reasons for submitting the complaint to the Inspectorate, the expectations and the experiences when reporting to the Inspectorate. Interviews lasting 30–100 min were recorded with permission of the interviewee. After the interview, the recordings were listened again, and a summarizing report was made and sent to the interviewee for approval. New themes derived from the interview reports were added to the questionnaire. New themes included for instance expectations regarding measures that lie within the competence of the Inspectorate as opposed to complaint boards, health‐care sectors other than hospitals and subjects that can be complained about (e.g. complaints procedure of complaint boards at hospitals). Face validity and content validity were assessed by submitting the questionnaire to two of the people who had been interviewed previously and three employees working at the complaints desk of the Dutch Health‐care Inspectorate, because of their experience with communicating with patients with complaints.

The questionnaire contained three domains: (i) characteristics of the person and complaint (subject and severity of physical injury); (ii) peoples' motives and expectations when reporting to the Inspectorate; and (iii) what is achieved by reporting. Severity of physical injury caused by the situation the complaint was about was measured on a 5‐point scale (1 = no physical injury, 2 = slight physical injury, 3 = severe physical injury, 4 = permanent physical injury, 5 = death). The questions about expectations were in the form of statements for which respondents could indicate how important the specific statement was to them. Subsequently, respondents were asked to what degree they felt that these statements actually applied (experiences). People's expectations making the complaint (from ‘not important’ to ‘most important’) and experiences with the reporting (from ‘no’ to ‘yes’) were measured on a 4‐point scale. According to the theory of responsive regulation, milder to more severe measures that could be taken by the Inspectorate were included to assess whether respondents agree with the stick or carrot approach. Examples of the questions about the expectations are ‘I made my complaint to the Inspectorate because I wanted to improve quality of care’ or ‘I made my complaint to the Inspectorate because I wanted the care provider in question to be punished’. Subsequently, examples of the questions about experiences are ‘Making my complaint to the Inspectorate led to the quality of care being improved’ or ‘Making my complaint to the Inspectorate led to the care provider in question being punished’.

Selection of the study population

The questionnaire was sent to all 343 people who submitted a complaint to the Inspectorate between August 2012 and November 2012.

Several inclusion criteria were formulated as follows:

The complaint has to be submitted by a member of the public/patient, not a care provider.

The complaint must be about health care (so general questions or complaints about the Inspectorate itself were excluded).

Handling of the complaint must be closed from the perspective of the Inspectorate, and the complainant had to have been informed about the closure by letter, so as to minimize the risk of respondents assuming that their response would have an impact on how their complaint would be dealt with.

An employee of the Inspectorate ensured the complaints met the inclusion criteria.

As described earlier, the Inspectorate is expected to only handle complaints by members of the public when they are severe or structural. Therefore, based on the information from the Inspectorate, two groups could be distinguished within the sample in advance: members of the public whose complaints were handled by the Inspectorate (n = 92, 27%) and those whose complaints were not handled by the Inspectorate (n = 251, 73%), because of the considerations mentioned earlier.

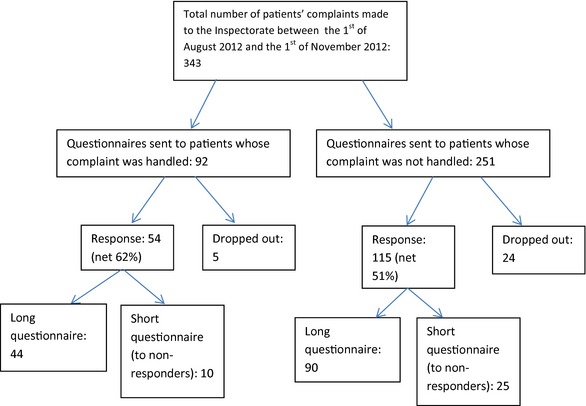

Two reminders were sent. After this, the response rate was modest (47%). A substantially abridged questionnaire was sent by post to non‐responders; 29 respondents dropped out because their addresses were incorrect, the person had moved, or the person was deceased. The response is shown in a flow chart (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of responses to the questionnaire.

Ethics statement

The protocol for this study was submitted to an external Medical Research Ethics Committee for formal ethical approval. This committee concluded that formal ethical approval for this study was not required according to Dutch law, as the study does not involve a medical intervention. Privacy was guaranteed because research data and addresses and names were kept separate. Questionnaires were sent by post by the Inspectorate itself. The questionnaires contained unique coded usernames and passwords, giving respondents the opportunity to complete the questionnaire online. It was stressed that people were entirely free to decide whether or not to complete the questionnaire and they could return the questionnaire to the researchers anonymously. It was explicitly stated that their individual answers to the questionnaire would not be revealed to the Inspectorate. The researcher kept a list of respondent codes that were also printed on each questionnaire, and the Inspectorate kept a list with the same codes and the associated names and addresses. This allowed response rates to be monitored and reminders could be sent by the Inspectorate to non‐responders. The list of codes was destroyed after 6 months.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using the software program STATA version 13 (StataCorp., College Station, Texas, USA). Background characteristics of the study population were compared to the characteristics of the Dutch population.36 Population characteristics and nature of the complaints are presented descriptively. Differences in severity of physical injury between the two groups (those whose complaints were and were not handled) were calculated using t‐tests to compare means.

Exploratory factor analysis (principal component analysis) with varimax rotation was carried out to identify latent relationships between the expectation variables. Communalities, eigenvalues, scree plots, explained variance and factor loadings were examined to determine the factor structure. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) test and Bartlett's test of sphericity were conducted with the purpose of confirming the adequacy of the sample for this analysis. Items with a factor loading ≥0.40 were included in scales. Reliability of the scales was assessed using Crohnbach's alpha. New variables were created for the scales to calculate mean scores of importance. Missing values, which were mostly related to respondents who completed the short questionnaire, were left out. Differences between the scores of the groups whose complaints were and were not handled were analysed using t‐tests. Differences were considered significant if p < 0.05. Percentages of which expectations are actually met according to the respondents were calculated by adding scores 3 and 4 of each variable.

Results

The response rate to the questionnaire was 54%. Basic study population characteristics are shown in Table 1. Background characteristics are not available for all respondents. Slightly more than half of the respondents were female. Relatively more respondents were aged 40–64 than in the Dutch population at large. The study population consisted of relatively more well‐educated people and relatively few people with ethnic backgrounds other than Dutch.

Table 1.

Background characteristics of the respondents (n = 129–131) compared to the Dutch population

| N (Respondents) | % | Dutch population (aged 18 and older) 201336% | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 128 | ||

| Female | 70 | 55 | 51 |

| Male | 58 | 45 | 49 |

| Age | 129 | ||

| 18–39 | 16 | 12 | 34 |

| 40–64 | 79 | 61 | 45 |

| 65 and older | 34 | 26 | 21 |

| Educational level | 129 | ||

| Low (none, primary school or pre‐vocational education) | 30 | 23 | 30* |

| Middle (secondary or vocational education) | 37 | 29 | 40* |

| High (professional higher education or university) | 60 | 46 | 28* |

| Unknown | – | 2 | |

| Ethnicity | 131 | ||

| Dutch | 127 | 97 | 79 |

| Other | 4 | 3 | 21 |

*These percentages apply to the Dutch population aged 15–65 in 2012.

Nature and subject of complaints

Table 2 shows the type of care that complaints made to the Inspectorate were about. Three types of care were complained about most often: 22% about nursing homes and residential care, 19% about hospital care and 19% about mental health care. Fewer than 15% of the complaints were about care provided by general practitioners, care for disabled patients, care in private clinics, care involving medical technology, home care, dental care, community care, drug therapy or physical therapy.

Table 2.

Type of care that complaints made to the Inspectorate were about

| Type of care complaint is about | N = 133 (%) |

|---|---|

| Nursing homes/residential care | 22 |

| Hospital care | 19 |

| Mental care | 19 |

| Drug therapy | 14 |

| General practitioner | 11 |

| Care for disabled | 8 |

| Private clinic | 7 |

| Medical technology | 5 |

| Home care | 4 |

| Community care | 2 |

| Physical therapy | 1 |

| Other | 18 |

Four of ten (39%) respondents submitted complaints concerning interpersonal conduct, and 37% of the complaints involved medical treatment (Table 3). However, almost all complaints about interpersonal conduct were submitted in combination with another subject. One of five respondents complained about a lack of information, quality of nursing care or collaboration between care providers. Other complaints concerned the complaints procedure of the care provider, organizational aspects or sexual harassment. A substantial proportion of respondents used the ‘other’ category and the accompanying option for an open answer. Box 1 shows some examples of complaints described in the open answer option.

Table 3.

Subject of complaints made to the Inspectorate

| Subject of complaint | N = 133 (%) |

|---|---|

| Interpersonal conduct | 39 |

| Medical treatment | 37 |

| Information or education | 23 |

| Nursing care | 22 |

| Collaboration between care providers | 22 |

| Complaints procedure | 14 |

| Organizational aspects | 10 |

| Sexual harassment | 9 |

| Other | 38 |

Box 1. Examples of complaints by respondents (handled and not handled), derived from open answer option.

Not handled:

Poor hygiene on the nursing ward. Cleaners who do not understand the word ‘cleaning’. Nurses who do not wash their hands.

Tubes with blood were left unattended in the hallway.

Medication that my cardiologist says I have to use (because of a metal cardiac valve) was not delivered. As a result, I had to go to the hospital urgently with the ambulance because of heart problems.

Errors were regularly made with medication, wrong dose of insulin, wrong antibiotics, for example after switching the type of antibiotics, the old one was given. It seems as if the referrals do not happen.

Cardiologist kept practicing although he was banned. Patients were not informed.

The complaint concerns unsuccessful operations, lack of supervision, off‐label medication with serious side–effects.

Handled:

Wrong insulin injection, several times. Wet pyjamas, not changed 3 times a day […] Eating times forgotten, food and drinks left for days […]

That pregnyl could not be obtained through the regular channels, but through web shops for bodybuilders.

The call made by a child to 911 was not accepted three times. After twelve hours, I alerted 911 again. Then, they reacted.

Title misuse, fraud.

Aggressive cleaning products are within reach for the clients at bath times.

In more than half of the cases (52%), another person was involved in the complaint than the complainant themselves, for instance spouse, child, parent or grandparent (not in table).

The severity of the physical injury caused differed significantly between the two groups: respondents whose complaints were handled reported an average of 2.9 on a 5‐point scale, while respondents whose complaints were not handled reported an average of 2.1 (not in table).

Expectations from submitting complaints to the Inspectorate

Table 4 shows the factor analysis conducted for the expectation variables. The KMO test of sampling adequacy and Bartlett's test of sphericity were used for confirming the adequacy of the sample for the analysis. The obtained values were 0.832 and 0.000, respectively. The factor analysis produced three meaningful scales, clearly distinguishing between different perspectives. The first scale refers to the consequences for the care provider (6 items, α = 0.85, explained variance 65%). The second scale refers to the public domain: the quality of health care in general (4 items, α = 0.77, explained variance 25%). The third scale refers to the individual domain: the benefits of complaining for the person that made the complaint (4 items, α = 0.79, explained variance 9%). Two items were excluded from the scales because they seem to be more general and less tangible consequences of making a complaint to the Inspectorate. One of them, ‘to prevent the complaint from remaining indoors’ (avg score of importance: 2.9), did not fit in any of the scales. The other one, ‘to ensure the complaint to be taken up at a higher level’ (avg score of importance: 3.3), cross‐loaded on two of the three scales. Table 4 also shows average scores of importance according to respondents of the specific expectations and the three scales developed. Furthermore, the expectations are shown separately for the two groups (complaint handled vs. not handled). Expectations regarding the dimension ‘benefits for quality of care in general’ were considered most important by respondents, followed by expectations regarding ‘personal benefits’. Expectations regarding ‘specific consequences for the care provider’ were considered to be least important. A significant difference was only found between the two groups for one item (financial compensation for the damage to be offered).

Table 4.

Factor analysis of what respondents expected from making their complaint to the Inspectorate and average scores of importance for the scales that were developed (1 = not important to 4 = most important)

| Avg. score for handled complaints (N = 37–42) | Avg. score for complaints that were not handled (N = 77–85) | I made my complaint to the Inspectorate because I wanted… | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3.6 | 3.5 | Benefits for quality of health care in general | |||

| 3.6 | 3.6 | The care institution to learn from my complaint | −0.0302 | 0.4967 | 0.2651 |

| 3.7 | 3.5 | To prevent it happening to others | −0.0374 | 0.6821 | 0.0065 |

| 3.6 | 3.6 | To improve the quality of health care | 0.0947 | 0.7667 | 0.0407 |

| 3.5 | 3.5 | To improve the safety of health care | 0.0339 | 0.6726 | 0.1504 |

| 2.7 | 2.7 | Personal benefits | |||

| 2.5 | 2.8 | To restore my sense of justice | 0.4468 | 0.1202 | 0.5439 |

| 2.8 | 2.9 | A solution to my problem | 0.3586 | 0.0511 | 0.7307 |

| 3.2 | 2.8 | To prevent it from happening to me again | 0.1232 | 0.3600 | 0.5101 |

| 2.2 | 2.5 | The damage to be repaired | 0.5201 | 0.0593 | 0.5947 |

| 2.1 | 2.4 | Specific consequences for care provider | |||

| 1.5* | 2* | Financial compensation for the damage to be offered | 0.6232 | −0.0388 | 0.3793 |

| 2.1 | 2.4 | The care provider in question to be banned from working | 0.8709 | −0.0023 | 0.1806 |

| 2.8 | 3 | The Inspectorate to have a hard‐hitting conversation with the care provider in question | 0.4700 | 0.2132 | 0.4470 |

| 2.1 | 2.4 | The care provider in question to be punished | 0.8628 | 0.0012 | 0.2191 |

| 1.6 | 1.7 | The department of the care institution to be closed | 0.6601 | 0.1489 | 0.1092 |

| 2.8 | 2.8 | To do my duty by making a complaint | 0.5118 | 0.1768 | 0.1533 |

| Crohnbach's alpha | 0.85 | 0.77 | 0.79 |

*Significant difference between groups, P‐value < 0.05.

**Bold values represent average scores of importance for the developed scales and the factor loadings of the items belonging to the specific scales.

Experiences when submitting complaints to the Inspectorate

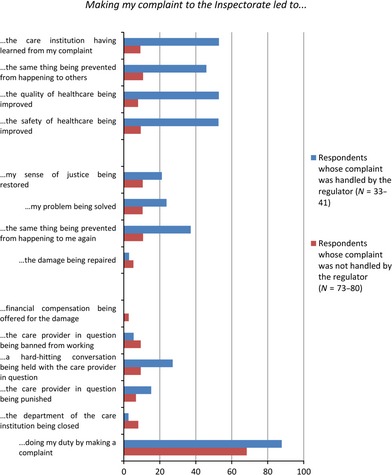

Figure 2 shows which aspects respondents felt had been achieved by making their complaint to the Inspectorate. A distinction was made between respondents whose complaints were handled by the Inspectorate and those whose complaints were not. Large differences were seen between the two groups. Respondents whose complaints were handled indicated that aspects were achieved more often than respondents whose complaints were not handled. About 50% of the respondents whose complaints were handled indicated that aspects regarding the dimension ‘benefits for quality of care in general’ were achieved. Fewer than 40% indicated that aspects regarding the other two scales were achieved (except ‘doing your duty’ – an aspect that respondents have more control of – which was achieved according to 68–88% of the respondents).

Figure 2.

Percentages of what is actually achieved according to respondents (items were measured on a four‐point scale (no to yes). Percentages presented in this figure are based on scores 3 and 4 of each variable.

Discussion

Several countries, including at least the UK and the Netherlands, are struggling with accountability issues when dealing with patients and their complaints.1, 3, 4, 28, 29, 30 This article contributes by giving insights into what role patients themselves expect their complaints to have in the regulatory process. Complaints of patients in this study were mostly about nursing homes, hospital care and mental health care. Most prevalent subjects of complaints were the medical treatment and interpersonal conduct, although the latter most often in combination with another subject. The self‐reported severity of the physical injury was significantly higher among patients whose complaints were handled by the Inspectorate. By reporting their complaint to the Inspectorate, patients aim to improve quality of health care. However, a minority felt this has been accomplished.

Expectations

Three main dimensions became apparent in what patients with complaints expect from a regulator: expectations regarding consequences for the care provider in question, personal benefits and benefits for quality of health care. Mean importance of the expectation scales was measured on a 4‐point scale (1 = not important, 4 = most important). This means that a score of 1.5 would be the neutral point on the scale and every score above 1.5 can be considered important. Most items were therefore considered important by respondents to some extent, but gradations can be distinguished. Expectations regarding improving quality of care were considered most important by respondents. Furthermore, personal benefits and consequences for the care provider were seen as less important. Particularly rigorous consequences are less favoured by respondents, which is in line with the stick or carrot principle of the theory of responsive regulation.14 The expectations largely correspond to what people expect of other complaints procedures, although slight variations can be observed. Complainants to complaint boards indicated that personal benefits were more important compared to complainants to the regulator. The same applied to complainants to disciplinary boards: consequences for the care provider were considered more important compared to what is important for complainants to the regulator.21, 24

The majority of the complaints by the study population (73%) are not handled by the Inspectorate. The self‐reported severity of physical injury in complaints that are not handled is lower than for complaints that are handled by the Inspectorate. The Inspectorate and complainants' estimates of the severity of physical injuries seem to correspond. However, no differences were found between the expectations of the two groups. This means that despite the severity of physical injury involved in the complaint, complainants' perceptions of the relevance of complaints differ from what the regulators perceive. People feel that their complaint indicates deeper structural problems that can recur. Sharpe and Faden9 have already argued that current patient safety evaluations tend ‘to reflect a narrowly clinical interpretation of harm that excludes non‐clinical or non‐disease‐specific outcomes that the patient may consider harmful’. As seen in other studies,37, 38, 39, 40 these results stress the importance of recognizing that lay people have their own interpretations of patient safety that may conflict with current evaluation methods.

Experiences

As in other studies about complainants' expectations,22, 23 this study found a gap between what complainants expect and what is achieved by submitting their complaint. For many respondents, it was unclear whether submitting their complaint had led to improvements, although this was their main driving force behind making a complaint. Although it is not surprising that what is achieved differs widely between the two groups, it should be noted that the group whose complaints were handled also felt that little was achieved by reporting to the Inspectorate. Previous research among complainants to hospital complaint boards revealed that most patients were not kept informed about the measures taken in response to their complaints.23 These results stress the need for complaint handlers to invest more in feeding back information to complainants about what actions were taken as a result of their complaint.

The respondents in this study seem to feel a sense of duty to make their complaints. They want to contribute to the improvement of quality of care and prevent recurrence. This indicates that they feel that they are a stakeholder in the process of improving health‐care quality and want to be involved. Other research among patients who experienced medical errors shows that those patients often have strong opinions and views about patient safety, accountability and system reforms.7, 25

Negative experiences of patients internationally created the demand for reforming safety cultures at care institutions. However, research suggests that those experiences have been neglected in patient safety reforms, due to power imbalances that exist between patients and care providers.7, 11

Using complaints for regulation

In this study, the complaints also concerned the ‘softer’ or non‐clinical aspects of caring, such as interpersonal conduct. Patients provide ‘soft intelligence’ – information about blind spots that care providers are unaware of5 – and the added value that this has for traditional monitoring systems such as incident reporting systems and regulatory visits has been proved.20 However, as the majority of the complaints in this study were not handled because the regulator is not there to deal with individual complaints, consideration should be given to whether complaints could be used more effectively for regulating health‐care quality systematically. Research has demonstrated that most medical errors never result in a complaint, so cases where individual complaints are submitted provide a valuable window on patient safety in general.18, 19 Actually, the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Inquiry showed that individual complaints provided important signals for dramatic system failures,4 and it was recommended that complaints should be included in the regulatory process.8 In addition, it has already been stressed that setting up continuous and non‐sporadic public participation mechanisms and long‐term learning commitment are essential for good regulatory design and would ensure accountability.1, 14, 15, 16, 17

Strengths and weaknesses

The response rate in this study was modest, even after sending two reminders and a shortened questionnaire. There is therefore a risk of response bias. Non‐response analysis was not possible because no characteristics of the non‐respondents are available, in part due to meticulous privacy regulations. Some respondents contacted us with questions about the study. Others indicated that completing the questionnaire made them uncomfortable because it revived the situation that the complaint was about. This could be an important reason for the non‐response. Another reason could be that filing the complaint itself had already cost much effort, making people reluctant to participate.

The study population was not large; however, power was sufficient for the statistical analyses. Furthermore, the study population is older and more highly educated than the general Dutch population. This might be explained by the fact that this specific group feel more empowered to make their complaint to the regulator. Another observation is that respondents often chose the ‘other’ answer category and used the option of adding details about their complaint in open answer categories. This emphasizes the complexity and diversity of the complaints, which are not easy to subdivide into standard categories.

Conclusions

Complaints by patients and the use of complaints for regulation of health‐care quality are widely discussed topics in many countries. We were, however, concerned to note that no research has been carried out on what patients with complaints expect from a regulator. Patients with complaints and the Dutch Healthcare Inspectorate share a common goal: improving the quality of health care. Patients feel that they are a stakeholder in the process of regulating health‐care quality. The Inspectorate is not there to handle individual complaints. Patients who file a complaint with the Inspectorate seem to be aware of this, as evidenced by the low need expectations regarding personal satisfaction among patients who made complaints. The self‐reported severity of physical injuries caused was lower among complaints that were not handled, which is in line with the severity‐based assessment of the Inspectorate. However, patients' perceptions of the relevance of their complaint differ from what the regulators perceive. Furthermore, only a minority felt that their complaint led to improvements, which was the primary reason for patients making complaints. To improve this, the value of complaints for regulation could be disclosed at an aggregate level. Regulators should move away from traditional standardized procedures and favour more responsive and strategic approaches for responding to complainants. This approach needs to go beyond assessing against exclusively clinical standards to identify the range of social problems associated with complaints about health care.

Long‐term learning commitment through public participation mechanisms can have the effect of enhancing accountability and improving the detection of problems in health care. It is therefore worthwhile to explore which specific forms (including the use of complaints) are most desirable to the public, most suitable and provide a valuable addition to the regulatory process. A thorough examination should be made of what information complaints by patients contain and what they can contribute to existing monitoring systems. How to collect and utilize complaints data to improve the quality of health care at the system level is a challenge that it would be worth exploring.

Sources of funding

This study was funded by ZonMw, the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development, programme effective regulation.

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflict of interests.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the people who were interviewed and those who responded to the questionnaire for their co‐operation.

Note

This study was carried out independently of the Dutch Health‐care Inspectorate. Cooperation was provided by the Inspectorate through selecting and contacting complainants for this study, to protect their privacy.

References

- 1. Prosser T. The Regulatory Enterprise. Government, Regulation and Legitimacy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Healy J, Braithwaite J. Designing safer health care through responsive regulation. Medical Journal of Australia, 2006; 184: 56–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Francis R. Independent Inquiry into Care Provided by Midstaffordshire NHS Foundation Trust. January 2005–March 2009, Volume 1 London: The Stationery Office, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Francis R. Report of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Inquiry. London: The Stationery Office, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dixon‐Woods M, Baker R, Charles K et al Culture and behaviour in the English National Health Service: overview of lessons from a large multimethod study. BMJ Quality & Safety, 2014; 23: 106–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Adams SA, van de Bovenkamp H, Robben PB. Including citizens in institutional reviews: expectations and experiences from the Dutch Healthcare Inspectorate. Health Expectations, 2013. DOI: 10.1111/hex.12126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ocloo JE. Harmed patients gaining voice: challenging dominant perspectives in the construction of medical harm and patient safety reforms. Social Science & Medicine, 2010; 71: 510–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Clwyd A, Hart T. A Review of the NHS Hospitals Complaints System: Putting Patients Back in the Picture. London: Department of Health, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sharpe VA, Faden AI. Medical Harm. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Behr L, Grit K, Bal R, Robben P. Framing and reframing critical incidents in hospitals. Health, Risk & Society, 2015; 17: 81–97. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ocloo JE, Fulop NJ. Developing a ‘critical’ approach to patient and public involvement in patient safety in the NHS: learning lessons from other parts of the public sector? Health Expectations, 2012; 15: 424–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Beaupert F, Carney T, Chiarella M et al Regulating healthcare complaints: a literature review. International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance, 2014; 27: 505–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Victoor A, Friele RD, Delnoij DM, Rademakers JJ . Free choice of healthcare providers in the Netherlands is both a goal in itself and a precondition: modelling the policy assumptions underlying the promotion of patient choice through documentary analysis and interviews. BMC Health Services Research, 2012; 12: 441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ayres I, Braithwaite J. Responsive Regulation: Transcending the Deregulation Debate. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992. . [Google Scholar]

- 15. Grabosky P. Discussion paper: Inside the pyramid: towards a conceptual framework for the analysis of regulatory systems. International Journal of the Sociology of Law, 1997; 25: 195–201. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Grabosky P. Beyond responsive regulation: The expanding role of non‐state actors in the regulatory process. Regulation & Governance, 2013; 7: 114–123. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Walshe K, Regulating US. Nursing homes: are we learning from experience? Health Affairs, 2001; 20: 128–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bismark MM, Brennan TA, Paterson RJ, Davis PB, Studdert DM. Relationship between complaints and quality of care in New Zealand: a descriptive analysis of complainants and non‐complainants following adverse events. Quality and Safety in Health Care, 2006; 15: 17–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wessel M, Lynoe N, Juth N, Helgesson G. The tip of an iceberg? A cross‐sectional study of the general public's experiences of reporting healthcare complaints in Stockholm, Sweden. BMJ Open, 2012; 2: e000489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Levtzion‐Korach O, Frankel A, Alcalai H et al Integrating incident data from five reporting systems to assess patient safety: making sense of the elephant. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, 2010; 36: 402–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Friele RD, Kruikemeier S, Rademakers JJ, Coppen R. Comparing the outcome of two different procedures to handle complaints from a patient's perspective. Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine, 2013; 20: 290–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Friele RD, Sluijs EM, Legemaate J. Complaints handling in hospitals: an empirical study of discrepancies between patients' expectations and their experiences. BMC Health Services Research, 2008; 8: 199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bismark MM, Spittal MJ, Gogos AJ, Gruen RL, Studdert DM. Remedies sought and obtained in healthcare complaints. BMJ Quality & Safety, 2011; 20: 806–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Friele RD, Sluijs EM. Patient expectations of fair complaint handling in hospitals: empirical data. BMC Health Services Research, 2006; 6: 106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Iedema R, Allen S, Britton K et al Patients' and family members' views on how clinicians enact and how they should enact incident disclosure: the “100 patient stories” qualitative study. BMJ, 2011; 343: d4423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ngo D, den Breejen E, Putters K, Bal R. Supervising the Quality of Care in Changing Health Care Systems. An International Comparison. Rotterdam: Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 27. IGZ . Leidraad Meldingen. [Guideline Reports]. Utrecht: IGZ, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sorgdrager W. Van incident naar effectief toezicht. Onderzoek naar de afhandeling van dossiers over meldingen door de Inspectie voor de Gezondheidszorg. [From incident to effective regulation. Investigation of the cases on reports by the Dutch Healthcare Inspectorate.], 2012.

- 29. De Nationale Ombudsman . Onverantwoorde zorg UMCG, Onverantwoord toezicht IGZ. Openbaar rapport over een klacht betreffende het UMCG en de IGZ te Utrecht. [Irresponsible care by UMCG, irresponsible supervision by IGZ. Public report on a complaint regarding the UMCG and the Dutch Health Care Inspectorate in Utrecht, the Netherlands.]. Den Haag: De Nationale Ombudsman, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 30. De Nationale Ombudsman . Geen gehoor bij de IGZ. [No response of the IGZ.]. Den Haag: De Nationale Ombudsman, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dutch House of Representatives . Report of general discussion, 33149 no. 8, March 16, 2012. 2012.

- 32. Kruikemeier S, Coppen R, Rademakers JJDJM, Friele RD. Ervaringen van mensen met klachten over de gezondheidszorg. [Experiences of people with complaints about healthcare.]. Utrecht: NIVEL, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sluijs EM, Friele RD, Hanssen JE. De WKCZ‐klachtbehandeling in ziekenhuizen: verwachtingen en ervaringen van cliënten. [Complaint handling according to the Clients Right to Complaint Act: expectations and experiences of clients.]. Den Haag: ZonMw, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Dane A, Lindert H, van Friele RD. Klachtopvang in de Nederlandse gezondheidszorg. [Complaint services in Dutch healtcare.]. Utrecht: NIVEL, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tyler TR. Social justice: outcome and procedure. International Journal of Psychology, 2000; 35: 117–125. [Google Scholar]

- 36. CBS . CBS Statline, 2013. Http://statline.cbs.nl/Statweb/.

- 37. Rhodes P, Sanders C, Campbell S. Relationship continuity: when and why do primary care patients think it is safer? British Journal of General Practice, 2014; 64: e758–e764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rhodes P, Campbell S, Sanders C. Trust, temporality and systems: how do patients understand patient safety in primary care? A qualitative study. Health Expectations, 2015. DOI: 10.1111/hex.12342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Buetow S, Davis R, Callaghan K, Dovey S. What attributes of patients affect their involvement in safety? A key opinion leaders' perspective BMJ Open, 2013; 3: e003104 DOI:10.1136/bmjopen‐2013‐003104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kuzel AJ, Woolf SH, Gilchrist VJ et al Patient Reports of Preventable Problems and Harms in Primary Health Care. The Annals of Family Medicine, 2004; 2: 333–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]