Abstract

Background

An increasing part of prescribing of medicines is done for the purpose of managing risk for disease and is motivated by clinical and economic benefit on a long‐term, population level. This makes benefit from medicines less tangible for individuals. Sociology of pharmaceuticals includes personal and social perspectives in the study of how medicines are used. We use two characterizations of patients' expectations of medicines to start forming a description of how individuals conceptualize benefits from risk management medicines.

Search strategy and synthesis

We reviewed the literature on patients' expectations with a focus on the influences on expectations regarding medicines prescribed for long‐term conditions. Searches in Medline and Scopus identified 20 studies for inclusion, describing qualitative aspects of beliefs, views, thoughts and expectations regarding medicines.

Results

A qualitative synthesis using a constant comparative thematic analysis identified four themes describing influences on expectations: a need to achieve a specific outcome; the development of experiences and evaluation over time; negative values such as dependency and social stigma; and personalized meaning of the necessity and usefulness of medicines.

Conclusions

The findings in this synthesis resonate with previous research into expectations of medicines for prevention and treatment of different conditions. However, a gap in the knowledge regarding patients' conceptualization of future benefits with medicines is identified. The study highlights suggestions for further empirical work to develop a deeper understanding of the role of patients' expectations in prescribing for long‐term risk management.

Keywords: long‐term conditions, management of risk, patient expectations, prescribing, sociology of pharmaceuticals

Background

Prescribing of medicines is one of the most common interventions in medical health care in the UK. Most prescriptions are issued in primary care and the annual cost for these exceeds £8 billion.1 Best practice for identifying persons at risk for disease, controlling symptoms, preventing acute events and managing sequelae is outlined in treatment guidelines. Early detection and treatment can be crucial in certain conditions. However, lowered thresholds for diagnosis of conditions associated with risk for future disease and the subsequent increase in treatment of such conditions introduce medicine‐taking to a large number of patients for whom the individual benefits are less obvious.2, 3 Examples of this are medicines that target elevated blood pressure or cholesterol, which are among the most commonly prescribed in the UK today.4

Awareness that the rising rates of prescribing for management of risk are accompanied by growing health‐care costs, widespread polypharmacy and more medication errors has led to efforts to improve the quality and safety in prescribing.5 The format of guidelines,6 style of medical practice7 and effectiveness of interventions directed towards key patient groups8 are areas that have been targeted – all of which are concerned with the prescriber or the system in which doctors and patients interact. These medicines management strategies tend to mention patients' views as important to consider,9 but retain a theoretical focus that limits the understanding to one based on medical definitions of health, illness and medicines.

Patients' usage of medicines can be seen as taking place at an intersection of medical science and daily lives. A vast body of knowledge in medical sociology describes many aspects of the interaction between people and medicines. Theory spans from individuals' compliance with medical instructions10, 11 via characterizations of the role of medicines in daily life12, 13 to considerations of the whole‐systems influences from patients, medical professionals, health‐care organization and governance.14, 15, 16, 17

Treatment for the purpose of management of risk for disease often targets asymptomatic conditions that require long‐term commitment by patients for potential beneficial effects to be demonstrable. One factor contributing to such commitment could be patients' expectations of future benefits or risk limitation arising from the prescribed medicines. In a theoretical description of the influences on patients' expectations on medicines, Thompson and Sunol emphasize the combination of cognitive and affective components and outline a range of personal and social factors that interplay with the information provided in a health‐care context.18 These include needs, values, experiences and emotions, as well as social norms, conditions and restrictions. Four types of expectations are identified: Ideal, predicted, normative and unformed (see Box 1). Patients' expectations regarding medicines for a number of long‐term conditions are described by Pound et al 19 in a meta‐ethnography of lay experiences of medicine‐taking. The authors mention a number of tangible effects that are used by patients while evaluating medicines by means of balancing of risks and benefits. The latter is composed of hopes for what medicines shall do: relieve or control symptoms, avoid relapse or hospitalization, slow or halt disease progression, prevent future illness or bring normality.

Box 1. Classification of patients' expectations suggested by Thompson and Sunol18 .

| Type of expectations | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Ideal expectations | Desired or preferred outcome based on idealistic beliefs regarding what a medicine can provide |

| Predicted expectations | Anticipated, realistic outcome based on personal or vicarious experience and other sources of knowledge |

| Normative expectations | What the patient thinks should or ought to happen, based on evaluation of what is deserved or socially endorsed |

| Unformed expectations | Inability or unwillingness to formulate what is expected due to fear, social norms or lack of knowledge |

| Health‐care context‐specific features that influence expectations | |

| Long‐term relation between patient and doctor | |

| Patient's emotional state may be shaped by illness experience and coping strategies | |

| Patient's knowledge about the condition and the effects of medicines may be very limited at the outset of a treatment, but increases over time | |

| Patients tend to use a subjective rather than objective set of notions when evaluating effects and services | |

Guided by these descriptions, we want to contribute new knowledge regarding patients' expectations of medicines prescribed for the purpose of management of risk. An empirical study is in progress. In the review and synthesis of literature reported here, we draw on qualitative work on long‐term medicine‐taking to start building an understanding of patients' expectations that is not limited to a medical definition of what medicines can and will do. Our research questions were ‘What are the influences on patients’ expectations regarding prescribed medicines?' and ‘What benefits do patients expect from medicines prescribed for long‐term prevention of disease?’

Methods

Search strategy

The database searches were set up to explore possible influences on patients' expectations of medicines. We used broad search terms to capture multiple aspects of our research questions. The database searches were then done by UD in two stages. The first step explored influences on patients' general expectations related to prescribed medicines. To find out specifically about treatments for the management of risk for future disease, the second step focused on patients' ideas about benefits with medicines prescribed for preventive purposes. Search terms are outlined in Box 2. Searches were performed in Medline and Scopus during August and September 2013 for publications from all available years.

Box 2. Search terms.

| Research question | Search terms | Hits |

|---|---|---|

| What are the influences on patients' expectations regarding prescribed medicines? | expect*AND influence* AND patient* AND prescribing OR prescription | 614 |

| expect*AND patient* AND primary care AND prescribing OR prescription | 135 | |

| influence* AND qualitative research AND prescribing OR prescription | 427 | |

| What benefits do patients expect from medicines prescribed for long‐term prevention of disease? | benefit* AND expect*AND qualitative research AND prescribing OR prescription | 225 |

| benefit*AND expect* AND medicine* AND patient* AND prevent* | 122 |

Selection of publications

The first step in the selection was scanning of article titles. Abstracts and full‐text articles were then checked by UD for descriptions of patients' accounts of using medicines and descriptions of influences on expectations. Due to the exploratory nature of this review, quality of the reported study was not used as a criterion for inclusion or exclusion. Instead, a careful examination of the applicability of the reported findings to the area of long‐term treatments was undertaken at the selection and synthesis stages. This assessment was done by UD with support from JR and TW. Articles were included in the review if they explicitly addressed qualitative aspects of patients' expectations, beliefs, views or thoughts about medicines prescribed for treatment or prevention of long‐term conditions and were written in English. Publications retrieved in the searches but excluded during the review process described practices or behaviours rather than views, professionals' expectations rather than patients', evaluations of specific interventions or solely quantitative aspects of patients' expectations. Articles about end‐of‐life care or medicines used for lifestyle or aesthetic purposes (obesity, facial acne, hair loss) were also excluded, on the basis that expectations related to these types of treatments are likely to be influenced by emotional factors that lie outside the scope of this research.

Extraction and synthesis of data

Data extraction and synthesis was done by open coding of reported influences on patients' expectations in the selected literature followed by a constant comparative thematic analysis20 and synthesis.21 Included articles were read closely to pick up data that was related to our research questions, and descriptive codes were allocated to pieces of text. The coding process was informed by, but not limited to, the aspects of patients' expectations on medicines discussed by Thompson and Sunol and Pound et al.18, 19 Codes were grouped together into categories that were adjusted as the analysis proceeded. By comparing extracts with the whole data set, including examination of cases that contradicted or deviated from the rest, the analytical categories were aggregated into themes that captured both general and specific aspects and similarities as well as differences in the dataset. The synthesis allows for themes to be formulated at a level ‘beyond’ description of the different types of data in separate studies so that new interpretations and explanations can be suggested. The extracted data together with contextual characteristics for the included studies are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

The dataset

| Authors (year) | Content | |

|---|---|---|

| Schofield et al. (2011)23 | Context | Semi‐structured interviews with 61 patients recruited from GP practices in three areas in the UK. Eligible patients invited via a letter from their GP. All participants had been prescribed antidepressants against depression and/or anxiety for at least a year. Purposive sampling is used to reflect the population of users of antidepressants in terms of age, sex, ethnicity and socio‐economic background. Most participants had experienced several episodes of depression at the time of the interview. |

| Findings |

|

|

| Conrad (1985)10 | Context | In‐depth interviews with 80 people with epilepsy about the meanings of medications in everyday life and why medicines are taken or not, carried out as a part of a larger project about living with epilepsy. All participants were or had been using medications against the condition. Recruitment was done via community channels. Participants are described as between 14 and 54 years old, mostly lower middle class and coming from urban areas in the United States. Interviews were held independent of medical and institutional settings. |

| Findings |

|

|

| Dolovich et al. (2008)24 | Context | The study aims to investigate expectations and influences thereon to find out if expectations have an impact on how medicines are used. Purposive sampling and recruitment through community and health‐care channels in Canada were used. The 18 participants represent different ages, living conditions and types of medicines used. Semi‐structured interviews were conducted around the medicines the participant considered most important and analysed using grounded theory. |

| Findings |

|

|

| Unson et al. (2003)29 | Context | With a stated aim to increase adherence, patients' beliefs about osteoporosis (OP) medication and medicines in general are assessed. Focus groups based on ethnicity was recruited via senior centres and housing estates in deprived areas in the United States. A convenience sample of 55 women aged 60 years or older participated. Most participants were on prescribed medication, but not for OP. Authors suggest that what is handled as a dichotomous question (treatment or not) in medicine is a more complex decision for patients, where heuristics, moral aspects and power relations are at play. |

| Findings |

|

|

| Granger et al. (2013) | Context | Mixed methods study aiming at exploring theoretical linkages between symptom experience over time and the meaning of medication adherence. Ten patients with chronic heart failure completed questionnaires measuring beliefs, behaviours, symptoms and satisfaction and were interviewed about the meaning associated with medicines. Patients were recruited by research nurses during an admission to a US university hospital with exacerbation of their condition. |

| Findings |

|

|

| Mazor et al. (2010)25 | Context | Telephone interviews with women ≥65 years that fulfilled WHO criteria for osteoporosis recruited from a multispecialty practice in Massachusetts, United States. History of dispensed prescriptions was used to classify participants into three groups of equal sizes: not using medication, started but discontinued medication and currently on medication. The study links core beliefs about medicines to patients' views on perceived need, safety and efficacy of a medication. |

| Findings |

|

|

| Nair et al. (2007)26 | Context | Semi‐structured interviews seeking to investigate patients' experiences with risk–benefit assessment when making decisions about treatment for type II diabetes. The 18 Canadian patients used different types of treatment and were recruited through community and health‐care channels. Both purposeful and theoretical sampling was used to ensure inclusion of patients that found treatment easy as well as difficult. The interpretation of the interviews was validated in a focus group session towards the end of the analysis process. |

| Findings |

|

|

| Smith et al. (2000)35 | Context | Experiences, concerns and willingness to participate in decision making about medicines were explored and compared between patients with the three conditions. Group interviews were arranged via voluntary organizations for each condition in the UK. |

| Findings |

|

|

| Cranney et al. (1998)30 | Context | In an investigation of barriers to implementation of guidelines for hypertension treatment, UK healthy elderly patients' and GPs' perceptions of risks and benefits were addressed. Participants recruited via a GP practice (75 patients) and on a training course (121 GPs). Attitudes to risk with untreated hypertension and ideas about benefit from prescribed medicine were assessed with questionnaires accompanied by visual aids during semi‐structured interviews. |

| Findings |

|

|

| Leaman and Jackson (2002)31 | Context | Questionnaire completed by 216 patients from a single GP practice in the UK. A random sample of patients, stratified for age and gender, were asked to state the level of benefit requested for acceptance of a first, second and third medicine for treatment of hypertension. Benefit was represented with fixed levels of NNT(5). Hypothetical scenarios explaining the consequences of a myocardial infarction and some practical aspects of the treatment accompanied the questionnaire, and respondents were asked to answer with only these aspects in mind. |

| Findings |

|

|

| Fuller et al. (2004)32 | Context | Older people's attitudes to stroke prevention were examined by presenting probabilities of risks and benefits with warfarin treatment. People aged 66–97 years answered questionnaires about hypothetical scenarios of risk reduction and practical aspects of treatment. The 81 participants were recruited via an elderly medicine outpatient clinic at a large university hospital in the UK. |

| Findings |

|

|

| Hux and Naylor (1995)33 | Context | Data on benefit of lipid‐lowering medication from a large clinical study were presented in different formats (relative and absolute risk reduction, NNT, average and stratified survival) to 100 participants aged 35–65 recruited from an outpatient setting in Canada. Treatments were presented as free of charge, without side‐effects and suggested by a doctor in hypothetical scenarios. Participants' preferences and their stated certainty about the decision were recorded to investigate how the format of benefit data influences decisions about treatment. |

| Findings |

|

|

| Arkell et al. (2013)34 | Context | Experiences, attitudes and expectations about information given prior to starting anti‐TNF therapy were assessed in focus group interviews with ten rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients in the UK. All participants were currently on treatment and purposively sampled to represent different ages, disease duration and activity and anti‐TNF agent used. Data were analysed with a phenomenological approach. |

| Findings |

|

|

| Gale et al. (2012)36 | Context | Meta‐ethnography of qualitative literature on usage of medication for prevention of cardiovascular disease, seeking to explore variations in behaviour and implications for practice. |

| Findings |

|

|

| Sale et al. (2011)28 | Context | A phenomenological study conducted to investigate patients' experiences with the decision to take OP medication after sustaining a fracture. Participants aged over 65 years who had had a fracture in the last five years and were at high risk for having another one were recruited via an OP screening programme in Canada. Two‐thirds of the 21 patients were currently taking OP medication. Cost for medication was covered by a local drug plan for all participants. |

| Findings |

|

|

| Adams et al. (1997)37 | Context | Attitudes of patients with asthma to prophylactic medication are explored with a patient‐centred perspective. In‐depth interviews were carried out with 30 participants recruited from a GP practice in Wales. Participants represented different ages, social backgrounds and duration of asthma. |

| Findings |

|

|

| Stack et al. (2008)38 | Context | Patients' beliefs about multiple medicines are addressed in interviews with 19 patients diagnosed with cardiovascular disease and type II diabetes. Authors acknowledge that usage of many medicines is associated with poor adherence and self‐management in patients. Recruitment was done via two urban GP practices in the UK. |

| Findings |

|

|

| Marshall et al. (2006)39 | Context | Relations between level of cardiovascular risk, acceptance of treatment and demographic characteristics were investigated quantitatively. Patients without diagnosed cardiovascular disease from GP practices in the UK were invited to participate in coronary risk screening and a research study. Preferences regarding treatment in hypothetical scenarios were recorded from the 181 participants before the screening, and a second interview was conducted afterwards to see whether patients changed their minds when told about their own risk. |

| Findings |

|

|

UD undertook the searches and selection of publications and the initial open coding and synthesis. Discussion between UD and JR strengthened the interpretive validity by identifying areas of dissonance or uncertainty and refining the developing categories. All three authors participated in finalizing the themes. The criteria for trustworthiness proposed by Lincoln and Guba were used as a framework for the critical assessment of the emerging analysis.22

Findings

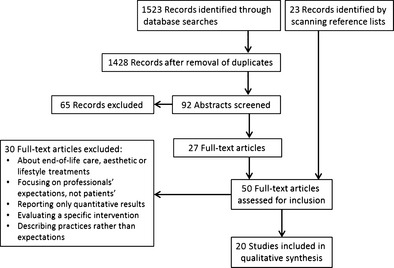

Combinations of the search terms in titles or abstracts yielded 1428 unique records. After scanning of article titles, 92 abstracts were reviewed and 27 full‐text articles assessed for inclusion. Reference lists in the reviewed papers were scanned for useful sources, which returned 23 more publications. The final synthesis included 20 publications, 12 of which were identified via databases and eight from the scanning of references. The selection process is outlined in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram of search results and selection of publications.

Four themes were identified from our synthesis of the literature, see Table 2. Influences on patients' expectations on medicines range from being highly specific and related to short‐term targets that medicines are hoped to help achieve to general views on whether medicines are useful at all. Practical experiences, personal beliefs and other people's opinions are influential as expectations are formed and develop over time.

Table 2.

Codes and themes

| Theme | Examples of codes |

|---|---|

| 1. A need to achieve a specific outcome | Medicines relieve symptoms, help avoid hospitalization, control disease or improve the conditions of daily life10, 23, 24, 25 |

| Confirmation of effects is sought, and lack of identifiable effects can lead to the medicine being seen as not useful10, 24, 26, 27 | |

| Medicines offer something beyond what is achieved by diet and exercise25, 28 | |

| A medicine prescribed for prevention ‘stops a heart attack’, ‘cures the bones’ or ‘does the job the doctor says need to be done’24, 29 | |

| Benefits with preventive treatments are overestimated30, 31 | |

| Patients wish for guarantees of survival30, 31, 32, 33 | |

| 2. Experiences and evaluation develop over time | Duration of illness influences understanding of disease and treatment effects26, 34 |

| Past bad experiences of side‐effects triggers a conscious evaluation of risks and benefits when new treatments are suggested26 | |

| Patients are seeking to confirm and adjust expectations26, 28 | |

| One's own experiences and those of other people are used in decisions about medicines24, 25, 28, 29, 34, 35, 36 | |

| Risks and benefits are balanced by patients in a different way than by doctors26, 29, 30, 31, 32 | |

| 3. Negative values – dependency, criticism and social stigma | Fear of getting addicted, associations with illicit substance use23, 37 |

| Hesitancy to be dependent on medicines for a normal life10, 37 | |

| The number of medicines used by one person can be seen as too high26, 27 | |

| 4. A personalized meaning of medicines; their necessity and usefulness | Medicines for different conditions are seen as being of different value38 |

| Patients with the same condition express diametrically different views about the treatment: necessary or of very limited value; as something that helps to live normally or the only way to avoid death; as a choice based on experience or a resignation in lack of other options23, 25, 37 | |

| Core health beliefs and notions of responsibility and morality influence decisions24, 25, 26, 39 |

A need to achieve a specific outcome

Expectations can be determined by the need to bring about a specific change. Medicines as an instrumental way to relieve both specific and wide‐ranging aspects of symptomatic illness are elicited by patients with depression needing to get better quickly after ‘hitting rock bottom’23 and epilepsy, where the medicines control seizures as well as reduce worry.10 Preventive medications are also seen as providing very specific benefits such as ‘stopping a heart attack’ or ‘curing the bones’.24, 29 These anticipations resemble a combination of the ideal and predicted expectations described by Thompson and Sunol.18 More general descriptions of medicines as effective tools to care for oneself beyond what can be obtained with diet and exercise are shared in interviews with patients suffering from heart failure and osteoporosis.25, 27 In terms of expressing expectations, it has been suggested that this is predominantly done by patients looking for specific outcomes, especially in relation to a condition that greatly impacts on their daily lives.24

The need for confirmation of a medicine's effect by symptom relief or some other immediately observable benefit is an often mentioned theme in relation to patients' expectations on medicines. Correspondingly, a lack of salient effect from the medicines may lead to loss of perceived meaning with the therapy in patients' views. This phenomenon points to the link between medicine‐taking and relief of symptoms being an important motivator for patients.10, 19, 26, 27

Patients' expectation that medicines will obtain certain effects also seems to apply to outcomes defined by someone other than the patient; both as a general ‘they should do what the doctor says need to be done’24 and more specifically mentioned by people with schizophrenia saying that medicines are used by doctors to control patients' behaviour and make it acceptable to society.35

In relation to expectations on medicines for risk reduction, several studies report that patients overestimate the possible benefits with preventive treatments: The requested reduction of risk for cardiovascular events and stroke in return for the effort of taking medicines every day is much higher than clinically available, and when provided with information about the likely level of benefit, patients tend to decline treatment referring to potential side‐effects.30, 31

In interviews with elderly patients about their willingness to use anticoagulants to prevent stroke, patients discussed the decision in terms of gambling and trade‐offs and expressed wishes for a guaranteed number of disease‐free survival years.32 The format of risk and benefit information when suggesting treatment for the management of risk seems influential on patients' decisions about treatment: Relative risk reduction yields much higher acceptance than number needed to treat (NNT) and disease‐free survival stratified between groups of patients gave more positive responses than when presented in a summarized way.33 The representation of benefits by absolute or relative risk reduction might be interpreted by patients as giving everyone a reduced risk, whereas with NNT, one single person gets the whole benefit of survival, making it less appealing. An expressed desire for a guaranteed number of years and the gambling and trade‐off language used by patients in discussions of the decision to accept or decline treatment also suggest that benefit is being conceptualized as an entity.

Experiences and evaluation develop over time

The expectations placed on medicines seem to be influenced by previous experiences of illness and medicine usage.10, 26 Predicted expectations18 dominate. These are weighted together in a continuous evaluation of whether and how to use the prescribed medicines and longer duration of illness seems to open up for a more nuanced description of expectations. A cyclical trial and evaluation, where patients balance their view on long‐term medicine‐taking with important experiences of improvement and worsening of their condition, make patients experts on their own treatment.23 This evaluation includes factors from the medical realm such as information about the condition, possible consequences and prescribed medicines as well as factors from other parts of life. In comparison with medical professionals' evaluation of medicines' appropriateness, patients use a shorter time‐scale when determining whether a medicine has beneficial effects. Their acceptance of risks or symptoms in relation to side‐effects and the number of aspects weighted into decisions also make patients' decision making different from that stipulated by a biomedical model of health and illness.29, 34

Aside from patients' own experiences, information from surrounding people is reported by several authors as influential on expectations. Doctors' advice30, 35 is balanced with personal and vicarious experiences,25 whereas academics and pharmaceutical industry are seen as less reliable sources.36 Development of trust in a prescriber seems to influence patients' decision to accept treatment, suggesting that it leads to expectations of beneficial effects,28, 36 while patients that retain a more critical stance compare prescribing to experimentation and question the doctor's knowledge about how a specific patient's body works.29 Consulting peers seems to be associated with patients being reluctant to accept treatment.28, 29

Patients' balancing of perceived beneficial and harmful effects changes over time.26, 28 Even patients that want their doctors to make decisions about treatments state a desire to be informed about the anticipated effects to participate actively in evaluation of the effects. Information for this purpose is also sought from public sources and the health‐care system to confirm and adapt expectations.24

Negative values – dependency, criticism and social stigma

The third theme encompasses negative aspects of medicines that are not derived from personal experience but instead related to general, societal views. It contains aspects of normative and unformed expectations.18 Certain types of medicines are described by patients as associated with addiction, dependency and illicit substance usage. Patients with asthma describe negative associations evoked by illegitimate use of steroids by bodybuilders and depressed patients hold initial reservations about treatment due to fear of addiction and social stigma. Patients describe both their own views, those of family members and reports available in the public realm as negatively influencing usage of medicines.23, 37

The number of medicines used by one person is also reported as something that may be valued negatively and evoke criticism from others. Patients question the helpfulness of taking a large number of medicines every day27 and may decline new suggested therapies on the basis that they are already using too many medicines.26

A personalized meaning of medicines; views on their necessity and usefulness

The fourth theme is built up by codes related to the utility of medicines in patients' lives, beyond that of providing immediate effects. This encompasses longer periods of time and wider aspects of living with illness. A recurring feature in the data set was the widely contrasting views patients share in relation to medicines' usefulness and necessity. This theme displays a combination of the four types of expectations described in Box 1.

When diagnosed with a chronic condition such as asthma or epilepsy medicines can play the role of either aids to obtain normality, by giving the patient control over symptoms, or obstacles cutting one off from normality by their association with social stigma and having an illness. However, such negative notions can be overcome by acquiring knowledge about a condition: Steroids form an essential part of the management of asthma, and medication against depression or epilepsy becomes accepted as a way to get on with life.10, 23, 37

A number of authors address the question about whether medicines are seen as necessary for life, health, etc. or if usage is optional, subject to personal inclination and should be balanced with life style changes to help manage the condition. Patients with multiple conditions may regard some medications more necessary than others, or some as being essential and other optional.38 In interviews with elderly women about osteoporosis medication, some participants stated that the medication was an inevitable, normative way to treat a condition associated with old age and therefore it would be effective, whereas others claimed that the natural ageing of the bones would limit the effectiveness of medication. In more general terms, prescription medication was described both as a way to obtain something beyond what diet and exercise could bring and as a ‘last resort’ that would only be used if those failed.25

In several studies, medicines are described as a commitment and ‘part of life’ by patients with chronic conditions. However, this can have both positive and negative connotations. Heart failure patients interviewed about their associations with medicines report taking them without knowing what benefits they will bring but ‘because I don't ever get better’ or ‘otherwise I will die'. On the other hand, the medicines also allow patients to ‘complete things during the day’ and ‘enjoy doing more things’.27 Similarly, depressed patients described the decision to use medicines in the long‐term as a conclusion based on experience, or as resigning to them being the only way to get by.23

One way to reconcile the opposing views expressed by patients living with the same chronic condition is the conclusion that expectations on medicines are influenced by deeply held personal views. This is described in terms of core beliefs about health and illness and feelings of responsibility or obligation to use medicines when diagnosed with a condition.26, 28, 39 Links between acceptance of treatment and demographic characteristics such as level of education or social class have been addressed and discussed by a few authors, but with inconclusive results.31, 39

Discussion

Our analysis identified four themes regarding influences on patients' expectations of medicines: a need to achieve a specific outcome; the development of experiences and evaluation over time; fear of dependency and social stigma; and personalized meaning of the usefulness and necessity of medicines. The desire for observable short‐term effects, usage of experiences and knowledge in a process of evaluation and notions of meaning linked to personal and societal values show that expectations on medicines are multidimensional and dynamic. A low acceptance for side‐effects, fear of dependency on medicines that do not have addictive properties and criticism against using a high number of medicines every day are influential factors that fall outside the biomedical model of health and illness.

In the specific case of expectations of benefit from medicines that are prescribed to manage asymptomatic risk conditions, our findings highlight a number of issues for consideration. Patients' desire for tangible benefits and specific outcomes in theme 1 and the role of experiencing ill health and medication effects in theme 2 point to a potential lack of meaningful ways to relate to and engage with medicine‐taking when the reason for treatment is a risk identified by one's doctor. An implication of this may be that patients interpret a decision about using such medicines as a dichotomous choice rather than as a way to influence the likelihood of outcomes. Another aspect is the perceived need for and acceptance of treatments for a growing number of conditions related to risk for future disease. Themes 3 and 4 point to possible issues regarding patients' acceptance of the concept of risk reduction by means of treating cohorts to decrease the number of acute events in a population. Prescribing of several medications to manage, for example, blood pressure may be considered medically appropriate if there is evidence for possible benefit from all of them. However, patients' views that it renders a number of daily tablets that is ‘too high’ or that higher blood pressure is part of ageing challenge the notion of benefit. In a wider sense, the increased availability and prescribing of medicines that target risk for future disease might influence personal and societal values held about using medicines for preventive purposes.

Influences identified in our analysis mirror the ideal, predicted, normative and unformed expectations described by Thompson and Sunol18 (see Box 1) and show how patients engage in practical evaluation of medicines as described by Pound et al.19 By combining one review and 17 primary data collections from several clinical fields that assess different qualitative aspects of medicine‐taking, we broaden the description of influences on patients' expectations on medicines. Our synthesis progress the understanding of patients' expectations by highlighting the importance of evaluation of medicines from an individual perspective. This finding is important for the further development of a theoretical description of medicines used for the purpose of risk management.

Codes and themes also resonate with an investigation of the impact of long‐term medicine‐taking on quality of life published just after the searches for this analysis were undertaken.40 There, the authors identify wishes for tangible effects, usage of different sources of information to confirm expectations, trusting or challenging recommendations from one's doctor, fear of dependency and complex decision making regarding the usage of a necessary but disliked medicine. Our study adds weight to the findings of Krska and colleagues by identifying these themes across a range of data sets.

Methodological limitations of the presented synthesis stem from the fact that although all the three authors were active in the decisions about searches and extraction as well as the coding and formulation of themes, the practical work was done mainly by one researcher. During the database searches, it became clear that ‘expectations’ is used liberally in the literature and it was difficult to specify narrow search terms that captured exactly what we were looking for. For this reason, it became apparent that searching reference lists of the included articles was also an important way to identify publications. Other limitations are due to the diverse nature of the primary data in the included publications, which is derived from narratives, interview material and data collected via questionnaires and describe both personal experiences and statements about hypothetical scenarios. Although the connection between using medicines and living with a long‐term medical condition has been highlighted,10, 37 only a few of the included publications discuss this issue in relation to their findings. This makes it difficult to determine whether the data represent specific expectations on medicines or thoughts about health, illness and care in general. An example of this is the discussion of a relation between readiness to make a decision about starting treatment and acceptance of it in a couple of the included publications, where the decision‐making process may be hampered by a patient's ambivalence vis‐à‐vis the diagnosis or the prescriber in clinical cases, and by difficulty to relate to the task in a hypothetical situation.

Assessment of truth value, applicability, consistency and neutrality helps determine the usefulness of findings in qualitative research.22 The recursion of codes and themes between this synthesis and other investigations of qualitative aspects of patients' views on medicines is an indication of good truth value and consistency of the results. However, the neutrality may be compromised by the fact that most of the included publications, although researching qualitative aspects of expectations, adopt at medical model where the aim to increase adherence to treatment becomes evident in the conclusions. Applicability of findings may differ between clinical fields. With regard to long‐term management of risk, the reviewed literature contains descriptions of some elements that relate to patients' decisions to accept or decline medicines. However, gaps remain in the theoretical understanding of how benefits with such medications are conceptualized, and how this may interrelate to prescribing for such purposes. This gap will be addressed in new empirical research. We are currently undertaking a study exploring patients' expectations on risk management medicines in an area where prescribing is high due to health policies' focus on early intervention, cardiovascular disease.

Conclusions

Unwanted effects of the increasing prescribing of medicines in the UK are the growing burdens of medication‐related problems, waste and costs for patients and the NHS. In addition to interventions framed as medicines management, addressing the social aspects of health, illness and medicines could offer a way to understand and address more aspects of the increasing levels of prescribing in primary care in the UK.

The stochastic nature of usage of medicines for the purpose of risk management, where time to beneficial outcome and distribution of benefit in a group of treated individuals are impossible to predict, makes patients' conceptualization of benefits an interesting and important but also under‐researched element of prescribing. Whereas medical and economic arguments for risk management medications can be gathered on a population level, findings in this qualitative synthesis suggest that individual patients are influenced by many more types of knowledge and values in a continuous, personal evaluation of whether to start and continue using medicines.

A deeper exploration of how patients conceptualize benefits with medicines prescribed to manage risk is the objective of our next study, involving interviews with patients at different levels of risk for cardiovascular disease. Building on this review, the aim will then be to develop a fuller theoretical understanding of how this topic can contribute to improved usage of medicines.

Source of funding

The research was funded by the Institute of Psychology, Health and Society, University of Liverpool, UK.

Conflicting interests

The authors have no conflicting interests to report.

References

- 1. Payne RA, Avery AJ. Polypharmacy: one of the greatest prescribing challenges in general practice. British Journal of General Practice, 2011; 61: 83–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hunt LM, Kreiner M, Brody H. The changing face of chronic illness management in primary care: a qualitative study of underlying influences and unintended outcomes. Annals of Family Medicine, 2012; 10: 452–460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Moynihan R, Doust J, Henry D. Preventing overdiagnosis: how to stop harming the healthy. British Medical Journal, 2012; 344: e3502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. New Health and Social Care Information Centre . Prescriptions Dispensed in the Community; England 2003–13. Leeds: Government Statistical Service, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Duerden M, Millson D, Avery A, Smart S. The Quality of GP Prescribing. An Inquiry Into the Quality of General Practice in England. London: The King's Fund, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Guthrie B, Payne K, Alderson P, McMurdo ME, Mercer SW. Adapting clinical guidelines to take account of multimorbidity. British Medical Journal, 2012; 345: e6341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Reeve J, Bancroft R. Generalist solutions to overprescribing: a joint challenge for clinical and academic primary care. Primary Health Care Research & Development, 2014; 15: 72–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Patterson SM, Hughes C, Kerse N, Cardwell CR, Bradley MC. Interventions to improve the appropriate use of polypharmacy for older people. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2012; 5: CD008165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Duerden M, Avery T, Payne R. Polypharmacy and medicines optimisation making it safe and sound London: The King's Fund, 2013: 32. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Conrad P. The meaning of medications: another look at compliance. Social Science & Medicine, 1985; 20: 29–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Donovan JL, Blake DR. Patient non‐compliance: deviance or reasoned decision‐making? Social Science & Medicine, 1992; 34: 507–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gabe J, Thorogood N. Prescribed drug‐use and the management of everyday life – the experiences of black‐and‐white working‐class women. Sociological Review, 1986; 34: 737–772. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Malpass A, Shaw A, Sharp D et al “Medication career” or “Moral career”? The two sides of managing antidepressants: a meta‐ethnography of patients' experience of antidepressants. Social Science & Medicine, 2009; 68: 154–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Abraham J. Sociology of pharmaceuticals development and regulation: a realist empirical research programme. Sociology of Health and Illness, 2008; 30: 869–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bell SE, Figert AE. Medicalization and pharmaceuticalization at the intersections: looking backward, sideways and forward. Social Science & Medicine, 2012; 75: 775–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Busfield J. ‘A pill for every ill’: explaining the expansion in medicine use. Social Science & Medicine, 2010; 70: 934–941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Williams SJ, Gabe J, Davis P. The sociology of pharmaceuticals: progress and prospects. Sociology of Health and Illness, 2008; 30: 813–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Thompson AG, Sunol R. Expectations as determinants of patient satisfaction: concepts, theory and evidence. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 1995; 7: 127–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pound P, Britten N, Morgan M et al Resisting medicines: a synthesis of qualitative studies of medicine taking. Social Science & Medicine, 2005; 61: 133–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Boyatzis RE. Transforming Qualitative Information: Thematic Analysis and Code Development/by Richard E. Boyatzis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 2008; 8: 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lincoln Y, Guba E. Establishing trustworthiness Naturalistic Enquiry. London: Sage Publications Ltd., 1985: 289–301. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Schofield P, Crosland A, Waheed W et al Patients' views of antidepressants: from first experiences to becoming expert. British Journal of General Practice, 2011; 61: 142–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dolovich L, Nair K, Sellors C, Lohfeld L, Lee A, Levine M. Do patients' expectations influence their use of medications? Qualitative study. Canadian Family Physician, 2008; 54: 384–393. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mazor KM, Velten S, Andrade SE, Yood RA. Older women's views about prescription osteoporosis medication: a cross‐sectional, qualitative study. Drugs and Aging, 2010; 27: 999–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nair KM, Levine MA, Lohfeld LH, Gerstein HC. “I take what I think works for me”: a qualitative study to explore patient perception of diabetes treatment benefits and risks. Canadian Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 2007; 14: e251–e259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Granger BB, McBroom K, Bosworth HB, Hernandez A, Ekman I. The meanings associated with medicines in heart failure patients. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 2013; 12: 276–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sale JE, Gignac MA, Hawker G et al Decision to take osteoporosis medication in patients who have had a fracture and are ‘high’ risk for future fracture: a qualitative study. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 2011; 12: 92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Unson CG, Siccion E, Gaztambide J, Gaztambide S, Mahoney TP, Prestwood K. Nonadherence and osteoporosis treatment preferences of older women: a qualitative study. Journal of Womens Health (Larchmt), 2003; 12: 1037–1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cranney M, Warren E, Walley T. Hypertension in the elderly: attitudes of British patients and general practitioners. Journal of Human Hypertension, 1998; 12: 539–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Leaman H, Jackson PR. What benefit do patients expect from adding second and third antihypertensive drugs? British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 2002; 53: 93–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fuller R, Dudley N, Blacktop J. Avoidance hierarchies and preferences for anticoagulation–semi‐qualitative analysis of older patients' views about stroke prevention and the use of warfarin. Age and Ageing, 2004; 33: 608–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hux JE, Naylor CD. Communicating the benefits of chronic preventive therapy – does the format of efficacy data determine patients acceptance of treatment. Medical Decision Making, 1995; 15: 152–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Arkell P, Ryan S, Brownfield A, Cadwgan A, Packham J. Patient experiences, attitudes and expectations towards receiving information about anti‐TNF medication–”It could give me two heads and I'd still try it!”. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 2013; 14: 165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Smith F, Francis S‐A, Rowley E. Group interviews with people taking long‐term medication: comparing the perspectives of people with arthritis, respiratory disease and mental health problems. International Jorunal of Pharmacy Practice, 2000; 8: 88–96. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gale N, Marshall T, Bramley G. Starting and staying on preventive medication for cardiovascular disease. Current Opinion in Cardiology, 2012; 27: 533–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Adams S, Pill R, Jones A. Medication, chronic illness and identity: the perspective of people with asthma. Social Science and Medicine, 1997; 45: 189–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Stack RJ, Elliott RA, Noyce PR, Bundy C. A qualitative exploration of multiple medicines beliefs in co‐morbid diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Diabetic Medicine, 2008; 25: 1204–1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Marshall T, Bryan S, Gill P, Greenfield S, Gutridge K , Birmingham Patient Preferences Group . Predictors of patients' preferences for treatments to prevent heart disease. Heart, 2006; 92: 1651–1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Krska J, Morecroft CW, Poole H, Rowe PH. Issues potentially affecting quality of life arising from long‐term medicines use: a qualitative study. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy, 2013; 35: 1161–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]