Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to gain better insight into the quality of patient participation in the development of clinical practice guidelines and to contribute to approaches for the monitoring and evaluation of such initiatives. In addition, we explore the potential of a dialogue‐based approach for reconciliation of preferences of patients and professionals in the guideline development processes.

Methods

The development of the Multidisciplinary Guideline for Employment and Severe Mental Illness in the Netherlands served as a case study. Methods for patient involvement in guideline development included the following: four patient representatives in the development group and advisory committee, two focus group discussions with patients, a dialogue session and eight case studies. To evaluate the quality of patient involvement, we developed a monitoring and evaluation framework including both process and outcome criteria. Data collection included observations, document analysis and semi‐structured interviews (n = 26).

Results

The quality of patient involvement was enhanced using different methods, reflection of patient input in the guideline text, a supportive attitude among professionals and attention to patient involvement throughout the process. The quality was lower with respect to representing the diversity of the target group, articulation of the patient perspective in the GDG, and clarity and transparency concerning methods of involvement.

Conclusions

The monitoring and evaluation framework was useful in providing detailed insights into patient involvement in guideline development. Patient involvement was evaluated as being of good quality. The dialogue‐based approach appears to be a promising method for obtaining integrated stakeholder input in a multidisciplinary setting.

Keywords: dialogue, evaluation, guideline development, mental health, patient involvement

Introduction

The involvement of patients in clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) is increasingly advocated. This is based on the argument that patients have the moral right to participate in decisions that affect them and that patient involvement can contribute to their implementation in practice.1, 2 In addition, patient involvement is thought to increase the relevance and quality of guidelines as their experiential knowledge can complement scientific evidence.3, 4 However, Bovenkamp and Trappenburg, based on a literature review on patient and public participation in guideline development, state that no empirical evidence was found to support this.5 According to Boivin et al.,6 the ‘paucity of rigorous process and impact evaluations limits current understanding of the conditions under which patient and public involvement programmes are most likely to be effective’ (p. 4). This statement underlines the need for in‐depth investigation, based on empirical research, of current initiatives of patient participation in guideline development.

The most common methods for patient involvement in guideline development are as follows: patient representation in guideline development groups (GDGs), patients reviewing final drafts of the guideline and consultation of patients through focus group discussions (FGDs) or questionnaires.7, 8, 9 Several barriers to and facilitators of patient involvement in CPGs have been identified. One concrete barrier is the difficulty of reconciling the preferences of patients with the views of professionals and with evidence from the literature.10 Other important barriers are the lack of clarity about the roles and tasks of patients in the process, lack of resources for supporting patient representatives in GDGs and doubts about the representativeness of the patients selected.10, 11, 12 Potential facilitators of participation include the active involvement of patients in all phases of guideline development, clarification of the role of patient representation, attention to adequate selection of patient representatives and provision of training and support for patient representatives.13, 14, 15, 16, 17 Considering the limited under‐standing of patient involvement, scholars have argued for more research to identify key components of successful patient involvement initiatives, better evaluation of patient involvement and research on alternative methods of patient involvement.6, 10

In this study, we develop a framework for monitoring and evaluating (M&E) patient involvement during the development of the Multidisciplinary Guideline on Employment and Severe Mental Illness1 in the Netherlands during 2010–2011.18 In the guideline development process, both common methods for patient involvement (patient representatives in the GDG and advisory committee, and FGDs) and innovative approaches (case studies and a dialogue session) were employed. Particular attention is paid to the use of a dialogue‐based approach in the reconciliation of preferences of patients and professionals. This study aims to provide insights into the process and the outcomes of patient participation in CPGs and to contribute to the development of comprehensive approaches for the M&E of patient involvement.

Methods

This section first provides a detailed description of the case under study. Second, the monitoring and evaluation framework which was developed to study the case is presented. Last, the methods used for monitoring and evaluating the case study are described.

Case description

The case study involves patient participation in the development of the Multidisciplinary Guideline on Employment and Severe Mental Illness. This guideline provides recommendations for supporting people with chronic and severe mental illnesses in employment, with a focus on job tenure.19 Box S1 provides information about the organizations that were involved.

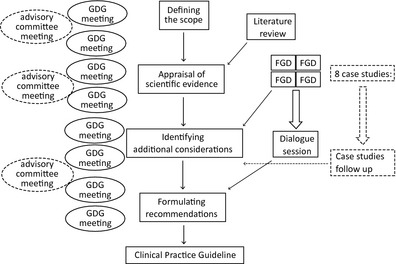

A GDG took the main role in developing the guideline, with its work monitored by an advisory committee. Among the nine GDG members were two patient representatives, one of whom changed jobs during the process and no longer formally represented a patient organization. Two of the twelve members of the advisory committee were patient representatives, one of whom joined halfway through the process. Over a period of 2 years (2010–2011), the GDG and the advisory committee met, respectively, eight times and three times to formulate recommendations concerning five key research questions. The literature searches were performed by an information specialist. Reviewing and writing tasks were divided among the GDG members. In addition, four focus group discussions (FGDs), a dialogue session and eight case studies were held to obtain insights from practice. Figure 1 provides a schematic representation of the different steps and activities in the guideline development process.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the steps and activities in the guideline development process.

Four FGDs were held separately with patients (n = 8), expert patients2 (n = 10), family members (n = 9) and professionals (n = 7). The four FGDs had a similar design and aimed at the articulation of the participants’ needs regarding employment and severe mental illness.

The FGDs were followed by a dialogue session in which fourteen participants from the FGDs took part, including patients (5), expert patients (3), family members (3) and professionals (3). In the dialogue session, the findings from the FGDs were presented to verify and complement them. After this, participants formulated recommendations for each key research question of the guideline. They did this in small, mixed groups of two or three participants and presented their recommendations to the group. The FGDs and the dialogue session were organized and facilitated by the research manager (second author) and a researcher from the Athena Institute (first author), who also acted as the monitor of the process. For each session, a summary report was produced and sent to the participants for a member check.

For the eight case studies, three persons were interviewed per case: a patient, an employer or manager, and a job coach. The interviews were carried out by the research manager, a research assistant and a patient representative who was a member of the GDG. They made a case description for each case. Members of the GDG assessed the case descriptions and subsequently formulated additional questions. In a second interview round, a follow‐up of the case studies was carried out in which the patient and job coach together reflected on developments in the past months. In addition, questions raised by the GDG members after the first round of interviews were addressed. The combined results from both interview rounds were integrated in a report in which the results were presented per key research question.

The results from the FGDs dialogue session and case studies were presented during meetings of the GDG and advisory committee. A draft of the guideline was sent to professional organizations for feedback, after which the final guideline was sent to the involved professional organizations for formal approval.

Development of a monitoring and evaluation framework

To assess the participation process and its outcomes, an M&E framework with quality criteria was developed. The framework is based on one previously used for evaluating stakeholder participation in health research agenda setting, as well as the results of an inventory of patient participation in clinical guideline development.7, 20 The main categories and criteria of the existing framework were adopted, while specific indicators were reformulated in terms of guideline development processes. The two main categories in the framework were the process of patient participation in guideline development and the outcomes of patient participation in guideline development. Process‐related criteria included involvement of patients, process structure and process management. Outcome‐related criteria specified direct outcomes and indirect outcomes of patient involvement. The quality of patient involvement is determined by the extent to which the process and outcomes of patient involvement meet the indicators of these criteria which are presented in Box S2. M&E comprises a reflexive process, following principles of Reflexive Monitoring in Action (RMA).21, 22 RMA aims to stimulate learning processes by enhancing reflection and dialogue between stakeholders concerning the process and outcomes. This is facilitated by a monitor who observes the process, gathers related data and reflects with stakeholders on the activities with the option to adapt the process.

Methods for monitoring and evaluation

In this study, data collection included document analysis, (participatory) observations and semi‐structured interviews. Data were collected by a monitor (first author). Drafts and final texts of the guideline, correspondence among the GDG members and advisory committee, and minutes of the meetings were subject to document analysis. Observations were made during the meetings of the GDG and the advisory committee, the four FGDs and the dialogue session. The monitor contributed to the design and facilitation of the FGDs and the dialogue session. Research logs were kept to document the observations and activities of the monitor. During several meetings, the monitor presented provisional findings to GDG members and the advisory committee and invited reflection on them. Some 26 semi‐structured interviews were undertaken in three phases of the guideline development process. An overview of the number of interviews per phase and the type of participants is provided in Table 1. The interviews were structured along the lines of the M&E framework, and its main categories and criteria formed the main topics in the interview guide. At the start of each interview, its purpose was explained to the participants. Sessions were audio‐recorded with consent of participants.

Table 1.

Overview of number and type of interviewees per round of interviews

| Interview round | Number of interviews | Type of interviewee |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5 | 2 guideline developers (chair and process manager) |

| 3 patient representatives (2 from GDG and 1 from advisory committee) | ||

| 2 | 10 | 3 guideline developers (chair, research manager and process manager) |

| 2 patient representatives (1 from GDG and 1 from advisory committee) | ||

| 5 professionals | ||

| 3 | 11 | 3 guideline developers (chair, research manager and process manager) |

| 4 patient representatives (2 from GDG and 2 from advisory committee) | ||

| 4 professionals |

Data from document analysis, observations and interviews were coded manually. Main codes and underlying themes were derived from the categories and criteria in the monitoring and evaluation framework. Indicators in the framework provided subthemes. Attention was paid to similarities as well as differences in the data. New codes or themes did not emerge. Initial coding of the data was performed by the first author, and codes were verified and agreed upon during review meetings with the third author.

At the start of the study, its purpose was explained to the members of GDG and the advisory committee and oral consent was obtained. Data were treated confidentially. Member checks were performed by sending a summary of the interview transcript to the interviewee and by presenting and discussing preliminary results during GDG meetings.

Results

The results of this study are described in two parts. The first part provides a general description of the process and outcomes of the various forms of patient participation in the guideline. The second part provides an evaluation of the quality of patient participation based on the indicators and criteria of the monitoring and evaluation framework.

Description of patient participation activities

Patient representatives in the GDG and advisory committee

The number of patient representatives in the GDG was two among ten members in total. The advisory committee initially counted one patient representative among twelve members. This was considered insufficient by many patient representatives, guideline developers and professionals. The monitor also signalled this as an issue needing attention. As a result, a second patient representative was invited by the guideline development organization to join the advisory committee halfway through the process. Observations showed that at least one patient representative was present at all meetings. Two of the four patient representatives were known to have personally experienced mental illness. It was not known whether the other two patient representatives had this experience because the personal background of patient representatives was not discussed during the process. Some of the professionals interviewed said that they could not distinguish patient representatives from the other GDG members because of their professional attitude.

The importance of patient involvement was explicitly addressed in the guideline development proposal and at the first working group meetings, but observations showed that attention to this topic declined during the process. Some patient representatives were uncertain about what was expected of them because the roles of patient representatives were not explicitly discussed. According to various interviewees, the involvement of the patient representatives contributed to the quality of guideline development throughout the whole process, from writing the draft of the proposal onwards. Observations and correspondence between GDG members indicated that the influence of patient representatives on decision making might have been limited because many decisions were not finalized during the meetings but were taken afterwards by a small group of guideline developers. Several patient representatives and guideline developers said that the influence of patient representatives on the process was most evident when discussing qualitative research and formulating additional considerations relating to conclusions from the literature.

The CDG chair and manager both considered patient involvement to be an important aspect of guideline development. They emphasized this during meetings and sometimes explicitly asked for patient representatives’ input although they did not formally organize additional support or training for patient representatives. Most patient representatives felt that they did not need specific training and support although one, who had joined later in the process, found it difficult to catch up and considered that support was limited.

All interviewees thought that the input from individual patient representatives was included in the guideline and that it was most evident in the critique of methods of vocational rehabilitation, reference to qualitative studies and the incorporation of evidence from grey literature.

The development of a version of the guideline for non‐experts was initiated during the last phase of guideline development. This was seen by the guideline developers as a way to enhance the practical applicability of the guideline. However, the non‐expert guideline version was unfinished by the end of the guideline development process. Additionally, an implementation plan was formulated to facilitate guideline implementation, but the actual implementation of this plan was beyond the scope of the guideline development process.

About half of the interviewed professionals and guideline developers mentioned that patient involvement helped to keep the guideline patient‐focused. Some of them specifically stated that the monitor had played a central role in this. Two patient representatives thought that they had learned more about guideline development, but this had a limited impact on the associated patient organizations because there was little communication between the patient representatives and their patient organization. One patient representative, however, said that her involvement in guideline development had led to a discussion in the patient organization on how to provide robust input to guideline development processes.

FGD and dialogue session

There were two FGDs with patients: one with ordinary patients and one with expert patients. Two other FGDs were held with family members and professionals. During the dialogue session, each of the groups participating in the four focus groups was represented and more than half of the fourteen participants were patients or expert patients. The monitor had suggested making a distinction between ordinary patients and expert patients in the focus group discussions because ordinary patients might have different views from expert patients, who are used to speaking in public and tend to have a broader view on issues. It was relatively easy to recruit expert patients through patient organizations. Finding ordinary patients initially took more effort, but they were eventually recruited through the network of professionals in the GDG. Patients with psychotic disorders were more highly represented than patients with other mental illnesses, mainly due to successful recruitment through a patient organization for psychotic disorders. Most interviewees did not find this problematic because psychotic disorders represent a substantial proportion of severe mental illnesses, and the issues raised in the FGDs were recognized by the GDG members as being of general importance. However, some professionals thought that perspectives of other severe mental illnesses were inadequately represented. Both guideline developers and professionals mentioned that diversity in ethnic background was limited, not reflecting the ethnic diversity of the patient population.

The efforts to communicate guideline‐related information in a comprehensive way in the FGDs and dialogue session made it possible for participants to quickly gain insights into guideline development. The monitor played a substantial role in this process by making suggestions for the structure of this dialogical approach and providing assistance to the facilitation of the sessions and to data processing. An important aspect of the design of the FGDs and dialogue session was that the different groups first met separately in homogeneous groups and then in mixed, heterogeneous groups. In this way, the different groups were able to articulate their needs and set an agenda before engaging in a mixed stakeholder dialogue. During the dialogue session, stakeholders formulated and agreed on guideline recommendations in small mixed stakeholder groups (see Box S3).

The FGDs provided an overview of the participants’ issues (see Box S3). Separating ordinary and expert patients appears to have been vindicated because ordinary patients generally formulated issues from an individual perspective, while patient experts mainly addressed contextual factors. The FGDs and dialogue session were specific items on the agenda of the GDG meetings and meetings of the advisory committee. Professionals interviewed indicated that the findings of the FGDs were generally familiar. Some of them thought this helped to give lived experiences a more central place in the guideline development process, while other professionals doubted the added value because many of the issues identified were already known to them.

One important issue which emerged was how to incorporate the information from FGDs and the dialogue session in the guideline text, because the procedure for this had not been set out in advance. The GDG members discussed this with the monitor and agreed that the results would be summarized per key question (by the research manager and monitor) and integrated under the ‘additional considerations’ chapter in the guideline, providing contextual information to complement evidence from the literature.

According to all interviewees, the input from patient FGDs and dialogue session was well represented in the guideline. Patient input was considered unique in emphasizing specific topics such as patients’ vocational limitations, their needs at the workplace and in terms of employment support. Although final guideline recommendations were generally based on evidence from the literature, findings of the FGDs and dialogue session were also taken into account. The implementation plan which was formulated also incorporated issues that were raised during the FGDs and dialogue session, such as the development of interventions for addressing stigma in the workplace and the role of patient organizations.

Case studies

Patient involvement in the case studies took place in two ways. A patient representative was always one of the three interviewers, and each case study included an interview with a patient alongside interviews with their employer or manager and job coach. As in the FGDs, patients with psychotic disorders were more highly represented in the case studies among the interviewees. In contrast to the FGDs, there was more diversity in terms of ethnicity.

The research manager indicated that case studies are an effective, simple method for involving all sorts of patients, especially those without prior knowledge of guideline development and those who have trouble speaking in groups. In addition, some interviewed patient representatives and guideline developers thought that the involvement of a patient representative as an interviewer in the case studies might have enhanced the patient perspective. Nonetheless, some patients still found it difficult to articulate their stories and voice their concerns. This might have made the patient perspectives less visible in the case studies than those of employers and job coaches.

The purpose of the case studies was unclear to many professionals and patient representatives in the GDG and advisory committee, possibly because limited time was paid to the case studies during GDG meetings. The inclusion of the perspectives of different stakeholders in each case was positively evaluated by professionals, guideline developers and patient representatives because it provided in‐depth insights into specific cases and included employers. Many GDG members initially expressed concerns regarding the way findings from case studies would be incorporated in the guideline. In response, GDG members agreed to summarize the findings per key questions in the guideline as was also decided for the FGDs (see Box S4).

The summarized findings of the case studies were included in the guideline under the separate heading ‘additional considerations’ next to the findings from the FDGs and dialogue session. All interviewees thought that the input from case studies was adequately represented in the guideline (see Box S5). Similar to input from the FGDs, input from the case studies emphasized topics such as patients’ vocational limitations, their needs at the workplace and in terms of employment support. Findings from the case studies were taken into account in the final guideline recommendations.

Evaluation of patient involvement in the monitoring and evaluation framework

Involvement of patients

Balancing the number of patient representatives and professionals

This criterion was partially met. In the FGDs and case studies patients were well represented, making up approximately half of the participants and interviewees. However, the number of patients was relatively low in the GDG and especially in the advisory committee, meaning that the ideal of equal numbers of patients vs. professionals was not achieved. It should be noted that the number of patient representatives was considered sufficient by most of the interviewees.

Addressing diversity of the patient population

Diversity of the patient population was partly addressed in the guideline. Diverse patient organizations and a variety of patients were represented in the guideline. However, ethnic diversity of the patient population was insufficiently taken into account, and there was no consensus among the interviewees as to whether diversity in types of severe mental illnesses was adequately addressed.

Adequate patient representation

The ability of patients to voice the patient perspective was mostly evaluated positively. However, representation appears suboptimal with respect to specific elements of guideline development as patient representatives did not always make clear they were speaking on behalf of patients and some patients in the case studies had trouble expressing themselves.

Process structure

Transparency of the process

The process of guideline development and patient participation was mostly considered transparent. The process was, however, considered less transparent with respect to the goal and structure of the case studies and the way that findings from the FGDs, dialogue session and case studies would be integrated into the guideline.

Clarity of expectations, roles and tasks

This criterion was partially met. The roles and tasks of patient representatives in the GDG and advisory committee were not always clear to them. No concerns were identified with respect to the tasks and expectations of patients in the FGDs, dialogue session and case studies.

Involvement throughout the process

The involvement of patients throughout the process was evaluated positively as patients were involved in all different phases of the guideline development process. The involvement of a patient representative in the writing of the draft proposal of the guideline was considered especially positive.

Involvement in decision making

This criterion was partially met. Patient representatives were involved in the decision‐making processes of the guideline in the same way as professionals in the guideline committee. However, as some final decisions were made by a small group of guideline developers, their influence was limited.

Process management

Facilitation of patient involvement

The facilitation of patient involvement was considered to be a positive aspect in this guideline. This was evident by the attention paid to patient participation throughout the process and the use of different forms of participation. The interviewees mentioned that the monitor played a role in stimulating attention to patient participation.

Addressing patients’ needs in the process

Patients’ needs were partly addressed during the guideline development process. Informal support was provided, but formal training and support were absent and sometimes needed.

Positive attitude towards patient involvement

This indicator was evaluated positively. A generally positive attitude was found among the members of the GDG and advisory committee, and in particular among the guideline developers involved.

Direct outcomes

Consensus on the content

This criterion was evaluated positively as there appeared to be general consensus on the content of the guideline.

Incorporation of patient input

All interviewees thought that the input from patient FGDs, the dialogue session, case studies and individual patient representatives was adequately represented in the guideline. Interviewees disagreed about the extent to which patient involvement through the FGDs and case studies added value to the guideline.

Practical relevance of the guideline

The practical relevance of the guideline was an issue that was evaluated mostly negatively. Although patient participation may have enhanced the practical applicability of the guidelines, many concerns were expressed about the extent to which the guideline could affect daily practice.

Dissemination of the guideline

This criterion was not met. Although the development of a non‐expert guideline and an implementation plan was initiated, these were unfinished by the end of the guideline development process. It should, however, be noted that implementation was considered beyond the scope of the guideline process.

Indirect outcomes

Learning processes of patient representatives and patient organizations took place to a limited extent during the guideline development process. About half of the interviews mentioned some type of learning, while the other half of the interviewees could not identify indirect outcomes resulting from patient involvement.

Discussion

The M&E framework proved to be a useful tool for providing detailed insights into the process and outcomes of patient involvement in guideline development. Patient involvement was generally evaluated as being of reasonably good quality. Those aspects that particularly contributed to the quality of patient involvement included the involvement of patients throughout the process, using different methods of involvement, consensus on the guideline content and the way in which patient input was incorporated in the guideline. The supportive attitude of professionals and guideline developers also appeared to be crucial for the quality of patient involvement. The role of the monitor was important because it increased the attention given to patient involvement and the resources available. This was possible within the scope of this study, but such a monitor is not usually available to guideline development processes. The need for such a monitor could be addressed by incorporating monitoring activities in the tasks of the project manager or chair or by allocating resources to appoint a monitor.

In this study, an innovative dialogue‐based approach was used to reconcile the perspectives of patients and other stakeholders. Our findings show that stakeholders were able to hold a constructive discussion based on each other's concerns and formulate shared recommendations for the guideline. This approach seems particularly useful in stimulating interaction in a multistakeholder setting and may help to increase the guideline's acceptability among different stakeholders.2, 23

Integrating the perspectives of patients with the evidence from the literature was a bigger challenge than reconciling the views of the different groups, mainly because the guideline development was primarily focused on evidence from the literature. According to Sackett,24 evidence‐based medicine should be equally based on service users’ values and expectations, individual clinical expertise and the best available clinical evidence. In this guideline process, a strategy was developed during the process for integrating the input from the FGDs, dialogue session and case studies into the guideline text as there was no predetermined strategy for this. This helped to give input from the patient perspective a place in the guideline text, but the evidence from the literature still formed the main focus. Renfrew et al. 25 provide an example of a more structured process in which evidence from the literature and the views of a broad constituency of stakeholders were more fully integrated to develop evidence‐based recommendations.

The evaluation revealed several other challenges to patient involvement in the guideline development process. First, it was difficult to represent the diversity of the target group in the guideline development process with respect to ethnic diversity and types of severe mental illnesses. When guidelines are relevant to a broad target group, attention should be paid to issues of diversity, for example by organizing additional FGDs. During this guideline development process, there were limited resources for including a diversity of stakeholders and, as a result, it is unclear whether saturation was reached for each stakeholder group. The dilemma of having to choose between either saturation of data or diversity and completeness is not easily resolved without adequate resources.26

Second, patient involvement was negatively influenced by the fact that some patient representatives did not clearly distinguish themselves from professionals in the GDG. This may be related to a high level of professionalization (proto‐professionalization) of patient representatives who learn about research during the process and adapt themselves to the scientific approach of professionals.27 However, it may also be the result of a lack of clarity concerning patient representatives’ roles and tasks and the lack of formal training and support provided to patient representatives. These findings indicate a need for additional efforts to communicate what is expected of patients, possibly in the form of training or support. Preparing an agenda or listing priorities from the patient perspective beforehand might also assist patient representatives to provide input.

Third, some professionals indicated that the added value of patients’ input from the FGDs, case studies and dialogue session was not evident as they were already familiar with most of the findings. However, patient involvement did contribute to greater priority being given to issues important to patients and to making practice‐based knowledge more explicit in the guideline. In addition, a high degree of consensus between professionals and patients contributes to triangulation and realizing evidence‐based medicine as defined by Sackett.24

The practical applicability of the guideline was an issue of concern among the interviewees. Although patient involvement contributed to connecting the guideline to practice, further implementation steps, maintaining the patient perspective, are still needed.6 To achieve this, a stronger link between guideline development and implementation is required. To assess patient involvement in the context of guideline implementation, long‐term outcomes should be incorporated in the monitoring and evaluation framework.

When interpreting the results of this study, one should keep in mind that the experiences reported may be more positive in terms of patient involvement than is the case for other cases of guideline development because there was a relatively high level of patient involvement and the guideline developing organizations were supportive of patient participation. In addition, the presence of the monitor further focussed attention on patient involvement. The results may be particularly relevant to the development of guidelines with a strong multidisciplinary character, mental health guidelines and guidelines based on limited scientific evidence.

Conclusions

This study provides insights into the quality of patient involvement in a particular guideline development process, using an M&E frame‐work developed for this purpose. The findings highlight the need to accommodate patient involvement and input into the professional and evidence‐led process, and the need for additional resources. A dialogue‐based approach appears a promising method, enabling a broad range of stakeholders to provide input tailored to the guideline topic and key research questions. More research is needed for further development of methods for reconciling the preferences of patients with evidence from the literature and to address patient involvement in the context of guideline implementation.

Funding

Financial support for this study was provided entirely by a grant from The Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMW). The funding agreement ensured the authors’ independence in designing the study, interpreting the data, writing and publishing the report.

Conflict of interest

We certify that there is no conflict of interest with any financial organization regarding the material discussed in the manuscript.

Supporting information

Box S1. Background to the Multidisciplinary Guideline Development Group.

Box S2. Monitoring and evaluation framework.

Box S3. Main findings from FGDs (A) and dialogue session (B).

Box S4. Example of a case study.

Box S5. An example of how input from the FGDs, dialogue session and case studies was integrated into the guideline.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the Trimbos Institute and the guideline development group members for their cooperation and providing us with a platform for this research.

Notes

Multidisciplinaire richtlijn ‘werk en ernstige psychische aandoeningen’.

We refer to expert patients in this study as: ‘patients who have been diagnosed with a mental illness and who are current or past users of mental health services providing services to other patients in the form of advocacy, self‐help, counselling, training and/or research’.

References

- 1. Rogers WA. Are guidelines ethical? Some considerations for general practice. The British Journal of General Practice, 2002; 52: 663–668. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Boivin A, Légaré F. Public involvement in guideline development. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 2007; 176: 1308–1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kelson M. Patient involvement in guideline development: where are we now? Journal of Clinical Governance, 2001; 9: 169–174. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Owens DK. Patient preferences and the development of practice guidelines. Spine, 1998; 23: 1073–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. van de Bovenkamp HM, Trappenburg MJ. Reconsidering patient participation in guideline development. Health Care Analysis, 2009; 17: 198–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Boivin A, Currie K, Fervers B et al Patient and public involvement in clinical guidelines: international experiences and future perspectives. BMJ Quality and Safety, 2010; 19: e22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Broerse JEW, van der Ham L, van Veen S, Pittens C, van Tulder M. Inventarisatie patiëntenparticipatie bij richtlijnontwikkeling [Inventory Patient Participation in Guideline Development]. Amsterdam: Athena Instituut, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Díaz Del Campo P, Gracia J, Blasco JA, Andradas E. A strategy for patient involvement in clinical practice guidelines: methodological approaches. BMJ Quality and Safety, 2011; 20: 779–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nilsen ES, Myrhaug HT, Johansen M, Oliver S, Oxman AD. Methods of consumer involvement in developing healthcare policy and research, clinical practice guidelines and patient information material. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2006; 3: 1–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Légaré F, Boivin A, van der Weijden T et al Patient and public involvement in clinical practice guidelines: a knowledge synthesis of existing programmes. Medical Decision Making, 2011; 31: E45–E74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Franx G, Niesink P, Swinkels J, Burgers J, Wensing M, Grol R. Ten years of multidisciplinary mental health guidelines in the Netherlands. International Review of Psychiatry, 2011; 23: 371–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. van Wersch A, Eccles M. Involvement of consumers in the development of evidence based clinical guidelines: practical experiences from the North of England evidence based guideline development programme. Quality in Health Care, 2001; 10: 10–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jarrett L, Patient Involvement Unit (PIU) . A Report on A Study to Evaluate Patient/Carer Membership of the First NICE Guideline Development. London: National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE), 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kelson M. The NICE Patient Involvement Unit. Evidence‐Based Healthcare and Public Health, 2005; 9: 304–307. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lanza ML, Ericsson A. Consumer contributions in developing clinical practice guidelines. Journal of Nursing Care Quality, 2000; 14: 33–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) . SIGN 50: A Guideline Developer's Handbook. Edinburgh, SIGN, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 17. van Veenendaal H, Franx G, Grol MH, van Vuuren J, Versluijs M, Dekhuijzen PNR. Patientenparticipatie in richtlijnontwikkeling. [Patient participation in guideline development, in Dutch] In: van Everdingen JJE, Burger JS, Assendelft WJJ, Swinkels JA, van Barneveld TA, de van Klundert JLM. (eds). Evidence‐based richtlijnontwikkeling: Een leidraad voor de praktijk [Evidence‐Based Guideline Development: A Guide for Practice]. Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum; 2004: 48–62. [Google Scholar]

- 18. van Erp N, Michon H, van Duin D, van Weeghel J. Ontwikkeling van de multidisciplinaire richtlijn ‘Werk en ernstige psychische aandoeningen’ [Development of the multidisciplinary guideline on ‘Work and severe mental illness’]. Tijdschrift voor Psychiatry, 2013; 55: 193–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. National Steering Group for Multidisciplinary Guideline Development in Mental Health & Trimbos Institute . GGZ‐richtlijnen – Trimbos. Available at: http://www.ggzrichtlijnen.nl/uploaded/docs/AUTORISEERBARE%20CONCEPTRICHTLIJN%20Werk%20en%20Ernstige%20Psychische%20Aandoeningen%201%20dec.pdf. accessed 18 March 2013.

- 20. Caron‐Flinterman JF, Broerse JEW, Teerling J et al Stakeholder participation in health research agenda setting: the case of asthma and COPD research in the Netherlands. Science and Public Policy, 2006; 33: 291–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Grin J, Weterings R. Reflexive monitoring of system innovative projects. Strategic nature and relevant competences. 6th Open Meeting of the Human Dimensions of Global Environmental Change Research Community, Bonn, Germany, 2005.

- 22. Regeer BJ. Making the Invisible Visible. Analysing the Development of Strategies and Changes in Knowledge Production to Deal with Persistent Problems in Sustainable Development. Oisterwijk: Boxpress, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wallerstein N. Powerlessness, empowerment, and health: implications for health promotion programs. American Journal of Health Promotion, 1992; 6: 197–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sackett D, Rosenberg W, Muir Gray JA, Haynes RB, Richardson WS. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn't. British Medical Journal, 1996; 312: 71–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Renfrew MJ, Dyson L, Herbert G et al Developing evidence‐based recommendations in public health – incorporating the views of practitioners, service users and user representatives. Health Expectations, 2007; 11: 3–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Elberse JE, Pittens CACM, de Cock Buning T, Broerse JEW. Patient involvement in a scientific advisory process: setting the research agenda for medical products. Health Policy, 2012; 107: 231–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Caron‐Flinterman JF, Broerse JEW, Bunders JFG. Patient partnership in decision‐making on biomedical research: changing the network. Science Technology and Human Values, 2007; 32: 339–368. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Box S1. Background to the Multidisciplinary Guideline Development Group.

Box S2. Monitoring and evaluation framework.

Box S3. Main findings from FGDs (A) and dialogue session (B).

Box S4. Example of a case study.

Box S5. An example of how input from the FGDs, dialogue session and case studies was integrated into the guideline.