Abstract

Background

In high risk, economically disadvantaged neighbourhoods, such as those primarily resident by black and minority ethnic groups (BME), teenage pregnancies are relatively more frequent. Such families often have limited access to and/or knowledge of services, including prenatal and post‐partum physical and mental health support.

Objective

To explore preferences held by vulnerable young mothers of BME origin and those close to them about existing and desired perinatal health services.

Design, setting and participants

Drawing on a community‐based participatory approach, a community steering committee with local knowledge and experience of teenage parenthood shaped and managed an exploratory qualitative study. In collaboration with a local agency and academic research staff, community research assistants conducted two focus groups with 19 members and 21 individual semi‐structured interviews with young mothers of BME origin and their friends or relatives. These were coded, thematically analysed, interpreted and subsequently triangulated through facilitator and participant review and discussion.

Results

Despite perceptions of a prevalent local culture of mistrust and suspicion, a number of themes and accompanying recommendations emerged. These included a lack of awareness by mothers of BME origin about current perinatal health services, as well as programme inaccessibility and inadequacy. There was a desire to engage with a continuum of comprehensive and well‐publicized, family‐focused perinatal health services. Participants wanted inclusion of maternal mental health and parenting support that addressed the whole family.

Conclusions

It is both ethical and equitable that comprehensive perinatal services are planned and developed following consultation and participation of knowledgeable community members including young mothers of BME origin, family and friends.

Keywords: community‐based participatory research, health services, mental health, parenting support, teenage mothers

Background

Teenage mothers (aged 13–20 years) often lack socio‐economic resources and support1 yet their physical and mental health needs cannot be minimized and, as parents, have a significant impact on the next generation. This project set out to explore the perinatal health needs of a highly vulnerable population of black and minority ethnic (BME) teenage mothers and explore existing and desired service preferences.

Teenage mothers are challenged as they are asked to achieve personal developmental tasks of adolescence crucial for their own well‐being, while at the same time, navigate the challenges of parenting.2 Teenage mothers have been found to be twice as likely as adult mothers to experience depression, which places them at risk for increased interpersonal struggles, and increases their chance of abusing or neglecting their children.3 Teenage mothers are not the only ones who suffer the adverse effects of their depression; children of adolescent mothers are likely to experience problems in their intellectual development and psychosocial functioning because of their mother's mental illness.1, 4 Several programmes have explored the crucial link between maternal mental health and child well‐being. For example, the Chances for Children: Teen Parent‐Infant Projects found that addressing mother–infant interaction is critical when depression is being treated5 and can increase positive parenting skills and subsequent child outcomes.6 Preventive interventions such as the Steps Toward Effective, Enjoyable Parenting Program (STEEP)7, 8 and the teen‐tot model7, 8 attempt to shield participants from stress‐related negative psychological health outcomes by providing social support, specifically to teenagers. These programmes are based on research suggesting that intensive family support for teenage mothers can yield positive results nearly a decade after intervention.7, 8

Access to, and use of, services

In a review of 145 studies on primary health‐care preferences,9 it was evident that inclinations to access services differed according to age, ethnicity, economic and health status, utilization of health services, family situation and religion. For example, BME patients had a greater preference than Caucasians for counselling and support within the primary health‐care context. Although not directly relevant to this study, it highlights the variation that exists and underscores that health services will be unique for this disadvantaged group of teenage mothers and patient preferences should be elicited.

Need for mental health services for young people

In a study of 16‐year‐olds reporting a need for mental health care, 20% did not receive care because they did not know where to go for services and 11% could not afford to pay for services.10 Girls were significantly less likely (35%) to seek out and receive needed services compared to boys (56%).10 However, according to a 2010 survey of 10 123 young people in the United States, girls were twice as likely as boys to experience unipolar mood disorders. In addition, young people in the 17–18 year age group are twice as likely to experience mood disorders as those aged 13–14 years.11 In addition to mental health problems, Sadler and Catrone12 discuss how developmental milestones occurring during adolescence are in direct conflict with the transition to parenthood, suggesting that not only is there a large need for mental health services but also for parenting services in this population. Particularly at risk are BME teenagers who have been shown to be less likely to seek services than Caucasian teenagers.13 And although analysis has identified thematic barriers to service use ‘uncertainty and soul searching, strength of the inner circle, shame and reluctance, belief in the system’,13 further research is necessary to discern the specific needs for BME teenage mothers.

While these data suggested a critical need for tailored mental health and parenting services for high‐risk, BME teenage mothers and their infants, the treatment utilization of established programmes, such as those provided by a locally based agency, Starfish Family Services, remained relatively low. According to brief, initial programme evaluation reports by this agency, a non‐profit organization serving vulnerable children and families in metropolitan Detroit, Michigan, United States of America (USA) for 50 years, the major obstacles for successful treatment delivery were as follows: problems with treatment engagement and recruitment, and relatively high attrition.14 A more in‐depth understanding of the needs and barriers experienced by local BME teenage mothers was needed to respond appropriately and provide tailored services. Building upon community‐based participatory research (CBPR)15 principles, a University of Michigan (UM) research team and staff from community‐based Starfish, partnered to engage key community stakeholders to explore this further by considering the perceptions of young BME teenage mothers and those close to them about existing services, and their preferences for potential health services during and after pregnancy.

Methods

Approach

In recognition of the importance of ensuring a localized perspective, a qualitative, CBPR approach16 was drawn upon. CBPR methods are based upon the premise that those who use services know best what they need17 and are similar to European studies of service user involvement in research18 and participatory action research.19 The purpose of CBPR is to increase knowledge on a particular subject with the broader goal of improving the health and quality of life of community members by bringing together researchers and communities in a balanced collaboration of equals.16 This can help address issues in a way that respects and understands the cultural context of the community.20 Although it is not always possible to fully engage the community in the entire process, a pragmatic approach is sometimes called for.21, 22 This research orientation actively involved the priority population in an atmosphere of reciprocal respect, curiosity and openness to diversity.20 Seeking and evaluating the advice, opinions and knowledge of community members increased the likelihood that changes in services reflect the needs of the culture and produce better outcomes.17

The priority community

The priority community was in Western Wayne County in metropolitan Detroit, Michigan, USA. According to 2010 census data, it has a population of 25 369. Of all babies born there, 15% are born to teenage mothers, and the 2010 Michigan League for Public Policy report indicated that 53% of births were covered by Medicaid, a government provided health insurance programme for persons with low income.23 Additionally, 85% of teenage births there in 2008 were to BME young women, almost half of whom have <12 years of education, and almost 100% of whom are dependent on federally funded health benefits. Census data indicated that nearly half of all children in this community under the age of five live in poverty.24 Starfish, a research partner in this project, provides mental health, developmental, educational and life skill services as well as tangible goods assistance for children, adults and families locally.

Procedure

Staff at Starfish recruited and employed two community research assistants (CRAs), both local BME residents. CRAs were selected on the bases of personal skills, familiarity with experiences of teenage mothers, local knowledge and credibility. One CRA, now in her early 20s, had been a teenage mother, while the other had teenage children and extensive local networks of family and friends. CRAs were funded by the project grant. The CRAs were trained to facilitate focus groups and interviews with local stakeholders. They were also responsible for recruitment, implementation and audio recording focus groups and the series of interviews.

As a component of CBPR, a community steering committee was developed and advised the project, meeting monthly for its duration. This comprised of 12 residents, including one or two teenage mothers, the parent of a teenage mother and representatives from locally based organizations, such as a teenage health centre, churches, hospitals and community‐based non‐profit (voluntary) organizations supporting local teenage mothers. The steering committee acted as a liaison between the community and academia, suggested contacts and strategies, and helped provide a balance in articulating community health priorities by giving additional perspective.25

The qualitative approach comprised of focus groups and individual interviews as primary data sources and was presented to the steering committee by research partner staff. The committee supported a participatory approach to consultation, the gathering of opinions and experiences of teenage mothers about the use, availability and gaps in local health and support services. The steering committee also offered suggestions for recruitment strategies and questions to ask during focus groups and interviews. The mental health needs of the participants were of particular concern, with the steering committee strongly advocating for teenage mothers and openly discussing strategies for engagement and difficulties with gaining the community's trust.

Participant recruitment

This study was approved by the University of Michigan Medical School Institutional Review Board (IRBMED) prior to recruitment of participants. Recruitment responsibilities were divided between CRAs with each identifying 5–6 teenage mothers for participation in the first group (only four participants attended) but took a more ‘active’ approach to recruitment for the second group (15 participants) by building and maintaining regular contact with potential participants. Eligibility criteria was as follows: being a BME woman who was currently a teenage mother, defined as between 13 and 20 years of age, or being a woman who had been a teenage mother within the past 10 years. Home‐based interview eligibility additionally included family members of current or former teenage mothers, health service providers in the community and local public school officials. CRAs posted fliers in prominent community locations, such as shopping centres and laundromats. Starfish staff also provided support, recruiting from community churches, teenage health centres and public high schools.

Convenience sample

A convenience sample of community stakeholders was utilized for focus group and interview purposes. Initially, a CRA considered contacts she knew personally and then used her network knowledge as a parent of a teenager at the local high school to recruit others from the school for the focus group or a home‐based interview. Face‐to‐face and telephone contacts were mostly used. Eligible participants were initially offered the focus group option and if not interested were then offered the individual interview choice. CRAs explained study goals, voluntary participation and obtained written consent during a home visit. In the case of willing mothers under the age of 18, a signature was obtained from her legal guardian or representative. Brief demographic information was also collected from the participant at this time. Oversampling was used to ensure sufficient participation in both focus groups, which were challenging to fill due to the strict eligibility criteria. Monetary incentives were provided for participant remuneration and to lessen any concrete barriers to participation. For each interview or focus group attended, each participant received $20. Additionally, transportation to and from focus group locations was provided through either a taxi service or a $10 fuel card.

Focus group and interview protocol

A standardized series of questions and prompts were developed to guide focus groups and interviews. Although there was some flexibility, the following questions were included:

Have you heard of Starfish or any of its services or programmes?

What are people saying in your community about Starfish and/or Baby Power (a time limited parenting intervention, developed by University of Michigan and jointly delivered with Starfish on their premises)?

Do you think these programmes are helpful or unhelpful?

What type of support did you receive during pregnancy?

Would you allow a professional to visit you and your child at home?

What are your views of services for moms at risk of depression or anxiety and difficult parenting?

Focus group participants and interviewees

Two focus groups were held in consecutive spring months in 2013 with four and 15 participants, respectively. All participants were, or had been, teenage mothers. Each group was facilitated by both CRAs and lasted approximately 90 min. Childcare was provided and used at both groups.

A pool of interviewees was gathered with 21 home interviews conducted by the CRAs in the same time period as focus groups. Teenage mothers were offered the option of focus group participation or a home interview dependent on personal preference. Table 1 shows the characteristics of focus group participants and interviewees.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants

| Characteristic | Focus groups (N = 19) | Interviewees (N = 21) |

|---|---|---|

| Relationship to teenage mother | ||

| Teenage mother | 100% (19) | 48% (10) |

| Parent of teenage mother | 0 | 19% (4) |

| Other relative | 0 | 9% (2) |

| Partner | 0 | 5% (1) |

| Church counselor | 0 | 5% (1) |

| Friend | 0 | 14% (3) |

| Average age | 23 years | 34 years |

| Age range | 18–30 years | 16–73 years |

| Race | ||

| African American | 100% (19) | 95% (20) |

| Native American | 0 | 5% (1) |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 74% (14) | 74% (14) |

| Married | 26% (5) | 26% (5) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 100% (19) | 90% (20) |

| Male | 0 | 5% (1) |

| Education | ||

| Less than high school diploma | 11% (2) | 14% (3) |

| High school diploma or GED | 37% (7) | 43% (9) |

| Some college | 32% (6) | 24% (5) |

| Vocational or technical degree | 11% (2) | 5% (1) |

| Bachelor's degree or higher | 0 | 9% (2) |

| No response | 11% (2) | 5 (1) |

| Paid employment outside the home | 32% (6) | 48% (10) |

| Not currently in school | 67% (14) | 67% (14) |

Interviewees showed a significantly wider age range, higher mean age and comprised both teenage mothers and network supporters.

Analysis

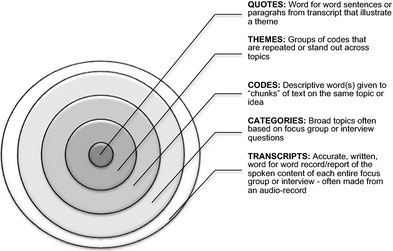

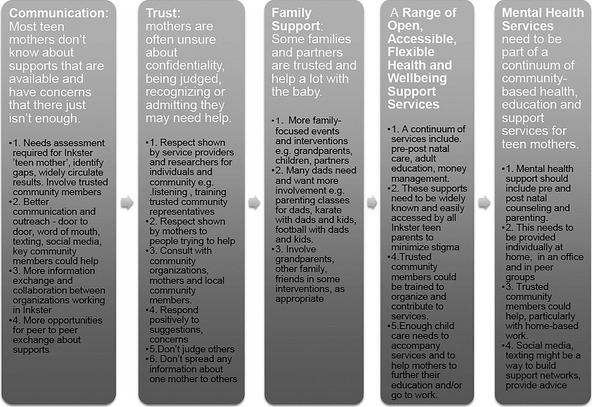

Grounded theory26 underpinned content analysis27, 28, 29 of the transcriptions from each of the focus groups and interviews. Figure 1 shows the definitions and interrelationship between components of this analyses process.30 A simplified version of this figure was used by the academic researcher to facilitate discussion about the process with the CRA and the steering committee. The analysis process was iterative following general steps including the following. Audio recordings from each group and interview were transcribed, then confirmed and edited by a CRA. Following discussion and agreement between the two analysts (an academic researcher and a CRA), transcripts were reorganized and combined in line with these categories. Subsequently, data were reduced through systematic open and axial coding to summarize emerging concepts based on patterns, repetitions or unique perspectives found in the text related to categories. Consultation took place between analysts on coding accuracy. Codes were grouped and summarized into emergent themes. During coding, quotes were identified to illustrate these. Triangulation resulted from further verification of content and interpretation with some research participants and the steering committee, using Figure 2 as a basis for discussion. Following these ultimate consultations with the steering committee, a Final Report, including recommendations, was prepared for dissemination to project participants, local agencies, funders and a city‐wide task force.

Figure 1.

Definitions of analysis terms and their interrelationships.

Figure 2.

Summary of themes and recommendations.

Results

Results fell thematically into two categories: use of current services and preferences for future services. Pseudonyms have been used with illustrative quotations to protect confidentiality.

Use of current services

Inadequate quantity and range of current services

There were concerns by many participants that there was a lot of unmet need for teenage mothers in this predominately BME community. This was combined with a lack of knowledge and/or uncertainty about the services that are available. The frequency of positive comments and enthusiasm about specific, quarterly community events, such as ‘community showers’ (expectant and other mothers' family and friends party) run by a large non‐profit organization, demonstrated a need for information, advice (e.g. accessing local parenting programmes) as well as practical and material support (e.g. baby clothes). At these events, opportunity was provided for the creation of new professional and informal social support networks. Similarly, another local service was mentioned by a few participants indicating needs for parenting classes, practical and emotional support. During a focus group, Jada described a service she had used:

…they teach you, they have parenting classes, or breastfeeding classes that you can go to. And like, one class they had was safe sleep class, and they provided a brand new pack and play. And after classes you have, like, one or two a month, however many classes you pick. You get to go in, like, their little store and they have, like, diapers (nappies) and wipes or baby food, and clothes and pacifiers and whatever you need is in the store.

Many participants in the study mentioned both benefits and barriers to existing parent support programmes. For instance, one young mother, Destiny, in a focus group commented:

I've heard about the ‘community baby shower’. I've been to a couple which was really nice. The food was healthy. A lotta people came out. I've heard about Starfish Family Services and the Early Head Start program [a family support program free of charge for families with children 0–3 years of age], which is good. The kids are learning a lotta information to go to the next level also go to kindergarten afterwards but the only thing is with the waiting list I hear a lotta people say the waiting list is too long or they can't get in because of their income or maybe or any other things or they might not be able to bring their child to school ‘cause some kids can't ride the bus, so, they don't have transportation to bring their child, so…but other than that Starfish is pretty good, they have a lotta programs.

Most teenage mothers did not know about the full range of available supports that were currently available

Most mothers had heard about the sponsoring community‐based not‐for‐profit agency, Starfish, but none had heard of the parenting programmes they provide. Beyond Starfish, other federal and countywide programmes were mentioned, but rarely. Suggestions were made for keeping mothers better informed about programmes. These included door‐to‐door flyers, use of social media, mail, internet and local television.

Suspicion and mistrust in the community

Teenage mothers were often unsure about the intentions of support agencies, confidentiality of their personal information, being judged by community or agency members and recognizing or admitting they may need help. A thread of suspicion and mistrust is part of local culture. As Tiana, an interviewee and teenage mother, voiced the opinion of most participants:

…the reason why I wouldn't reach out is because even though I do have a really, really strong support team, the trust issue. Just like everybody in this world knows somebody in (this community), I wouldn't want everybody to know my business because of the simple fact that you could go tell her, she could go tell you, and then everybody know my business. I trust you, but not you, to come into my home.

Another teenager during her focus group, Jada, preferred to go out of her home to access services but also shared her mistrust of people in authority when she described some of her concerns about home visits:

… when the teachers or whoever may come to your home they may be judgin'…of your home or you don't know what, you don't never know what people might say or [what] write down or you know sometimes you don't have control over. Especially people in (this community), you don't have control over where you came from or what you have in front of you so a lotta people judge people that live (here) and it's all over the news it's everywhere so, and like I said, that lady she came to my home and she was judgin' everything I did and that wasn't fair.

Preferences for future services

Increase in family‐focused support

Sometimes family members and partners are trusted and are actively involved in childcare and rearing. Support from extended family differed from one extreme to another, but it was often families to whom pregnant teenagers turned, even when support was withheld. Kayla found support from her family difficult to access and told her peers in the small focus group:

My mom stopped talking to me for three months. My dad really didn't care ‘cause we didn't have a strong relationship. And then a lot of other people in my family made a big deal about it because my son's daddy is older.

Some participants wanted the baby's father and his family to be more involved. A grandmother, Celia, during interview explained:

…sometimes they (young mothers) really want the father to just step in and just be there and just be a family because lotta people grew up in single homes and they just want their family to be together if they do get pregnant they just want, that father, the baby's, to be there and that's like the only thing that they're worried about is he gonna be there is, ya know so maybe reach out, I dunno, like can you get to the dads and tell them hey…do the right thing. (Laughs)

Increased accessibility to a range of group and individual, community‐based, health, welfare and education support services

There were many ideas for increased availability and for the characteristics of delivering health, welfare and education programmes to meet the needs of young mothers. Ideas included the following:

Prenatal and post‐partum physical and mental health medical care: There was an expressed need for accessible, community‐based obstetric and gynaecological health services that encourage regular and frequent use, staffed by supportive, skilled people who also offered continuity.

For example, Makayla shared her experiences in her focus group about the doula programme (a doula is a trained professional in the USA who provides emotional and physical support during the pregnancy, birth and post‐partum):

She [the doula] came to my house from when I was, like, five months pregnant and just came in every month to just talk with me, did little things. And when I end up having the baby she came to the hospital and was there. And then the little community baby shower. They had some good classes there [at Starfish] so, uh, stuff like that.

Mental health services must be part of this continuum

…because of my depression and it helped so, I think it it's a good program for people with depression problems especially during pregnancy (Lacey, focus group member).

Hormonal changes during the teenage years in combination with pregnancy and social pressures can make this a particularly difficult time.2, 31 Lacey went on to describe one of her post‐partum issues that were helped by individual counselling and therapy. She shared that:

I went to a therapist ‘cause…I was having post‐partum (anxiety and depression); cause when my daughter was born, the doctor had to use, they call it a, vacuum to pull her out. And it stretched her arms so she ended up getting [unintelligible] in her arm, which is basically just a tear or a stretch of the muscle. So like every time somebody saw and noticed it, I'd just start crying.

Childcare and parenting

Over half of all participants commented on the need for practical support with childcare and parenting in this community. Teenage mothers had often not completed schooling or entered the workforce but intended to do so. During a home interview, Shana, said:

…because for me, I wanted to go to school so, I was able to go to school and bring my son in to Early Head Start so I think it's pretty helpful.

Parenting can also be a big challenge, especially when self‐esteem is low or effective parent role models are absent as one interviewee, Dianna, who had been in foster care told us:

I was 14 but I had my child at 15. So I was in a teen program, and I went to parenting class because I wanted to actually know how it was, not being raised by my parents, but actually knowing how to raise my kid my way instead of my parents way. So I actually went to parenting class.

Professional and peer individual and group support: Other mothers and supporters commented on the potential benefits of other types of professional and peer support. Many participants liked groups rather than individual interventions. Unsurprisingly, all the focus group participants preferred groups as these comments by Barbara and Makayla show:

It gives you a lotta insight on everybody else's experiences…and also allows you to know that you're not alone.

Yeah and it's easier to speak up if you hear somebody else talkin' you think maybe I shouldn't say nothing but if somebody else say something you like, ok well, I kinda understand that I could speak on some of my situations.

Respectful and trustworthy providers: Confirming the views expressed by Jada (in focus group) Tiana (in interview) highlighted the underlying issue of trust with the service provider:

It's a trust issue because you're lettin' this person come into your home and so there, ya know, this person, she was goin' back, tellin' information which is supposed to be confidential. If it's just me, my child, and you, it's supposed to be confidential–not goin’ and tellin’, ya know, anybody else of what's going on or how things should be done.

Discussion

This project highlighted a number of important issues relevant to the development of services, particularly among vulnerable BME populations and where service uptake is a problem. The context of mistrust, often common in high‐risk neighbourhoods,32 shaped responses and findings. Yet, despite limitations, this project demonstrated the relevance of using a methodology embedded in the local community to enable ethical planning and development of services.17 It is important, however, that service changes then follow as a result of consultation and local participation, or it can potentially perpetuate social divisions and lack of trust.20 It is also worth noting that identifying and focusing on a high‐risk group, such as teenage BME mothers in need of extra support, may also have unintended consequences as it can reinforce that parenting is exclusively their responsibility as mothers, even though father involvement in parenting has been shown to be important.33

One of the reasons behind poor uptake of services was apparent. Underlying mistrust and suspicion meant that there is considerable dependence on ‘word of mouth’ as the primary method of communication among potential users of services. There were additional suggestions for improved communication and outreach strategies. These included door‐to‐door contact, flyers, inserts in local coupon mailings, word of mouth, texting, social media, community TV, local newspapers, as well as community events and informal and formal support networks, including peer‐to‐peer support.

The mistrust of ‘officialdom’ and each other among some vulnerable populations has many implications, not least for home visiting. This is often seen by providers as helpful outreach but can also be interpreted by the recipient as intrusive. It may lead to increased vulnerability and perceptions of them as inadequate, poor parents in need of help.34 This may have been reflected in the frequency with which teenage mothers in this study showed reluctance to express any need for help despite wide recognition that parenting can be a challenging stage of life and requires support. Reluctance to express any need for help may be influenced by peer pressure, pride and concerns about confidentiality.10, 35 Pregnancy and parenting may often be viewed as part of life that just has to be coped with. Admitting otherwise may be a sign of weakness. Admission of this in the community could expose one to the negative effects of stigma 35 including worry such as the potential of having children removed. Trust can be built when respect and reliability is mutually demonstrated by attitudes and actions, such as being non‐judgmental and respectful in approach, mindful of confidentiality and engaging trusted community representatives in decision making and power sharing.36

Building on this project, a comprehensive, collaborative need assessment is required in which teenage mothers and local community residents or activists identify service gaps and duplications and help shape the dissemination process about future service development. This continuum of well‐coordinated, community‐based services for teenage mothers could include pre‐ and post‐natal physical and mental health care, adult education, money management and parenting support.37 These support services need to be widely known and easily accessed by all locally resident teenage parents to minimize stigma. Trusted community members could be trained to organize and contribute to various services which may help increase use, extend support networks at the local level and positively impact cost. Sufficient childcare should be available to accompany services and to help mothers to further their education and/or employment. Lack of transport was often cited as a barrier to the use of services. Consideration needs to be given to this when services are organized and located.

The importance of including mental health services

Depression and anxiety are common among teenage mothers and may preclude engagement with support services, even when they are available.31 Mental health interventions require multiple approaches from individual to collective (e.g. assembly of peers at one of their homes, churches or other community setting), and the use of various technologies including social media and mobile phone use. A focus on young fathers could be considered as an aspect of intervention. Trusted community members could help, particularly with home‐based work.

Limitations of methodology

It was both a strength and weakness that local residents as CRAs were recruited to facilitate data collection. Utilizing CRAs, however, also brings the potential for bias beyond the divide between academicians and community members. Recruitment was enhanced but was also dependent on their age, gender, race, skills, networks and any perceptions held off, and by, them locally. In future, an alternative would be to recruit a team comprised of a community member and an outside professional with skills and experience to co‐lead and conduct research. This team would have the potential to carry the benefits of having a trusted community member (CRA) but would offer the reassurance of confidentiality from a service professional.

As this was not a random sample, generalizability is limited due to individual characteristics of the community and the dependence of participant selection by the CRAs. The study was also limited by its small and unequal sample size, particularly in the focus groups. The first group only had four mothers attend. However, the next focus group hosted nearly four times as many participants, making management and recording more challenging. Similar issues of challenges due to focus group size are noted by Morgan38 as well as Tang and Davis39 who suggest that focus groups range from 4 to 12 participants for quality data collection.

Lessons learned

The participation of the community in design and implementation of the research was valuable supporting community relevance and practicality. This involves additional time to build relationships, the development of simplified explanations and tools commonly used in research, for example Figs 1 and 2. Building and maintaining regular contact with potential participants prior to, and following focus groups and interviews, was important to ensure recruitment, attendance and follow through. A stronger role in analysis by a subgroup of the steering committee would have enabled greater inclusion of broader, local expertise and might have strengthened commitment to the research, extended local ownership of the findings40 and commitment to related service actions and built local capacity.20 However, the steering committee offered invaluable knowledge of community norms offering suggestions for style and vocabulary use by facilitators, typical schedules of teenage mothers in the area and better locations and times to hold groups.

Incentives were essential to engage local participants already managing many demands with few resources. It is suggested that in general, monetary incentives increase effort and participation.41 Due to the rates of poverty in the priority community, it is hypothesized that a higher incentive would have increased the likelihood of participation.42

Individual interviews were conducted to gather in‐depth information based on one participant's perspective and to allow participants to have confidentiality. Although data from individual interviews could have differed markedly from data obtained in focus groups, this was not the case and instead served to confirm focus group findings.

Conclusion

Our work suggests that input for service development needs to come from a broad perspective, including feedback from those who directly benefit from the service. Policymakers who want to improve access and use of existing services or want to develop better fitting services for teenage mothers of BME origin could in future more often use qualitative research approaches to obtain direct feedback from target populations.

Funding

The research presented was supported through the Michigan Institute for Clinical and Health Research Community University Research (MICHR CURES) Partnership Pilot Grant award (UL1RR024986 awarded to Maria Muzik).

Disclosures of conflicts of interest

None for any author.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to all the local residents who came to the focus groups or were interviewed about their views and experiences of services for teen mothers in their community, especially to Pam Nions and Ciara Harris, who both worked hard to organize and facilitate these. Pam was also involved in the analysis and interpretation of data. Recognition and much appreciation are also given to the community steering group who helped shape and inform this project. Finally, thanks to Karen Calhoun for her valuable guidance with the focus groups and Nicole Miller for additional support.

References

- 1. Osofsky JD, Hann DM, Peebles C, Zeenah CH. Adolescent parenthood: risks and opportunities for mothers and infants In: Zeanah CH. (ed.) Handbook of Infant Mental Health. New York: Guilford Press, 1993: 109–119. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lesser J, Anderson NLR, Koniak‐Griffin D. “Sometimes you don't feel ready to be an adult or a mom:” the experience of adolescent pregnancy. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 1998; 11: 7–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Barnet B, Liu J, Devoe M. Double jeopardy: depressive symptoms and rapid subsequent pregnancy in adolescent mothers. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 2008; 162: 246–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schore AN. The effects of early relational trauma on right brain development, affect regulation, and infant mental health. Infant Mental Health Journal, 2001; 22: 201–269. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mayers HA, Hager‐Budny M, Buckner EB. The chances for children teen parent‐infant project: results of a pilot intervention for teen mothers and their infants in inner city high schools. Infant Mental Health Journal, 2008; 29: 320–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Weinberg MK, Tronick EZ. The impact of maternal psychiatric illness on infant development. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 1998; 59(Suppl 2): 53–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Egeland B, Erickson MF. Lessons from STEEP: linking theory, research, and practice for the well‐being of infants and parents In: Sameroff AJ, McDonough SC, Rosenblum KL. (eds) Treating Parent‐Infant Relationship Problems: Strategies for Intervention. New York, NY, USA: Guilford Press, 2004: 213–242. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Akinbami LJ, Cheng TL, Kornfeld D. A review of teen‐tot programs: comprehensive clinical care for young parents and their children. Adolescence, 2001; 36: 381–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jung HP, Baerveldt C, Olesen F, Grol R, Wensing M. Patient characteristics as predictors of primary health care preferences: a systematic literature analysis. Health Expectations, 2003; 6: 160–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Samargia LA, Saewyc EM, Elliott BA. Foregone mental health care and self‐reported access barriers among adolescents. The Journal of School Nursing, 2006; 22: 17–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Merikangas KR, He JP, Burstein M et al Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication‐Adolescent Supplement (NCS‐A). Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 2010; 49: 980–989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sadler LS, Catrone C. The adolescent parent: a dual developmental crisis. Journal of Adolescent Health Care, 1983; 4: 100–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bains RM. African American adolescents and mental health care: a metasynthesis. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 2014; 27: 83–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Starfish Family Services . Community needs assessment: Western Wayne County, 2011. Unpublished Report.

- 15. Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB, Allen AJIII, Guzman JR. Critical issues in developing and following CBPR principles In: Minkler M, Wallerstein N. (eds). Community‐Based Participatory Research for Health: From Process to Outcomes. 2. San Francisco: Jossey‐Bass; 2008: 47–66. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community‐based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual Review of Public Health, 1998; 19: 173–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Minkler M, Wallerstein N Community Based Participatory Research for Health. San Francisco, CA: Jossey‐Bass, 2003. xxxiii, 490 pp. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wallcraft J, Schrank B, Amering M. Handbook of Service User Involvement in Mental Health Research. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Baum F, MacDougall C, Smith D. Participatory action research. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 2006; 60: 854–857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Israel BA, Coombe CM, Cheezum RR et al Community‐based participatory research: a capacity‐building approach for policy advocacy aimed at eliminating health disparities. American Journal of Public Health, 2010; 100: 2094–2102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bergold J, Thomas S. Participatory research methods: a methodological approach in motion. Historical Social Research/Historische Sozialforschung, 2012; 37: 191–222. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Macaulay AC, Jagosh J, Seller R et al Assessing the benefits of participatory research: a rationale for a realist review. Global Health Promotion, 2011; 18: 45–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Michigan League for Public Policy . Mothers and infants in Michigan communities: the other half, 2010. Available at: http://www.milhs.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/09/RS2010FINAL2.pdf. Last accessed 20 March 2014.

- 24. Inkster, Michigan (MI) Poverty Rate Data – information about poor and low income residents. Available at: http://www.city-data.com/poverty/poverty-Inkster-Michigan.html. Last accessed 6 May 2014.

- 25. Norris KC, Brusuelas R, Jones L, Miranda J, Duru OK, Mangione CM. Partnering with community‐based organizations: an academic institution's evolving perspective. Ethnicity & Disease, 2007; 17: 27–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Corbin JM, Strauss AL. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Los Angeles: Sage Publications, 2008. xv, 379 pp. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Charmaz K. Constructing Grounded Theory. Los Angeles: Sage, 2014. xxi, 388 pp. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Creswell JW. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. Los Angeles: Sage Publications, 2013. xxi, 448 pp. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mathison S. Encyclopedia of Evaluation. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005. xxxv, 481 pp. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Unger HV. Participatory health research: who participates in what? 2012; 13. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Birkeland R, Thompson JK, Phares V. Adolescent motherhood and postpartum depression. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 2005; 34: 292–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ross CE, Mirowsky J, Pribesh S. Powerlessness and the amplification of threat: neighborhood disadvantage, disorder, and mistrust. American Sociological Review, 2001; 66: 568–591. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Carlson MJ, McLanahan SS. Fathers in fragile families In: Lamb ME. (ed.) The Role of the Father in Child Development, 5th edn Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons Inc, 2010: 241–269. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Whitney P, Davis L. Child abuse and domestic violence in Massachusetts: can practice be integrated in a public child welfare setting? Child Maltreatment, 1999; 4: 158–166. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chandra A, Minkovitz CS. Stigma starts early: gender differences in teen willingness to use mental health services. Journal of Adolescent Health, 2006; 38: e1–e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Schout G, De Jong G, Zeelen J. Establishing contact and gaining trust: an exploratory study of care avoidance. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 2010; 66: 324–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. McCurdy K. Can home visitation enhance maternal social support? American Journal of Community Psychology, 2001; 29: 97–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Morgan DL. Focus groups. Annual Review of Sociology, 1996; 22: 129–152. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tang KC, Davis A. Critical factors in the determination of focus group size. Family Practice, 1995; 12: 474–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wallerstein N, Duran B. Community‐based participatory research contributions to intervention research: the intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. American Journal of Public Health, 2010; 100(S1): S40–S46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bonner SE, Sprinkle GB. The effects of monetary incentives on effort and task performance: theories, evidence, and a framework for research. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 2002; 27: 303–345. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Martin E, Abreu D, Winters F. Money and motive: effects of incentives on panel attrition in the survey of income and program participation. Journal of Official Statistics‐Stockholm‐, 2001; 17: 267–284. [Google Scholar]