Abstract

Objectives

Question prompt lists (QPLs) are structured lists of disease and treatment‐specific questions intended to encourage patient question‐asking during consultations with clinicians. The aim of this study was to develop a QPL intended for use by parents of children affected by attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Methods

The QPL content (111 questions) was derived through thematic analysis of existing ADHD‐ and QPL‐related resources. A modified Delphi method, involving a three‐round web‐based survey, was used to reach consensus about the QPL content. Thirty‐six experts were recruited into either a professional [paediatricians, child and adolescent psychiatrists, psychologists, researchers (n =28)] or non‐professional panel [parents of children diagnosed with ADHD, ADHD consumer advocates (n = 8)]. Panel members were asked to rate the importance of the QPL content using a five‐point scale ranging from ‘Essential’ to ‘Should not be included’.

Results

A total of 122 questions, including 11 new questions suggested by panellists, were rated by both panels. Of these, 88 (72%) were accepted for inclusion in the QPL. Of the accepted questions, 39 were re‐rated during two follow‐up survey rounds and 29 (74%) were subsequently accepted for inclusion. The questions covered key topics including diagnosis, understanding ADHD, treatment, health‐care team, monitoring ADHD, managing ADHD, future expectations and support and information.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first ADHD‐specific QPL to be developed and the first use of the Delphi method to validate the content of any QPL. It is anticipated that the QPL will assist parents in obtaining relevant, reliable information and empowering their treatment decisions by enhancing the potential for shared decision making with clinicians.

Keywords: attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder, ADHD, Delphi method, question prompt list, shared decision making

Introduction

Attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental condition which is commonly identified during childhood and has a worldwide prevalence of 5.3%.1 The disorder is characterized by symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity which can impair the child's academic2 and social functioning.3 Although ADHD emerges through a combination of biological, genetic and environmental factors,4 many parents of children diagnosed with ADHD experience negative sentiments as a result of their child's situation5 stemming from public resistance towards a biomedical conceptualization of the disorder.6 Furthermore, the use of first‐line stimulant medications remains highly contentious,7, 8, 9, 10 complicating parents’ treatment decisions11 and affecting adherence to prescribed regimens.12

Thus, it is critical that parents and their children are well informed about ADHD and the importance of appropriately prescribed treatments through the provision of accurate and tailored information. Previous studies have highlighted that parents obtain ADHD‐related information from a number of sources.13, 14 Paediatricians are the most commonly accessed source of information (89%) followed by books (78%), general practitioners (65%), schools (61%), the Internet (59%) and the media (54%).13 Health‐care professionals (HCPs) are an important source of reliable information which can assist parents during treatment decision making.14 However, parental satisfaction with ADHD‐related information obtained during clinical consultations can be improved.15, 16 Parents have reported problems communicating with HCPs including difficulty obtaining information from the clinician, receiving insufficient information and/or receiving excessive information which is not in line with their specific concerns and is difficult to absorb in the short consultation time.17, 18 These problems can ultimately lead to misconceptions about the child's condition, an inability to express treatment preferences and poor adherence to treatment regimens.17

Therefore, it is essential that HCPs engage with parents during clinical consultations as this can improve treatment adherence and overall health outcomes for the child.19 The process of shared decision making (SDM) is increasingly becoming recognized as the gold standard of health care in a range of disease states.20 As defined by Charles et al.,20 SDM consists of four key characteristics: (i) participation of patients and their physicians; (ii) both parties are engaged in the treatment decision‐making process; (iii) both parties exchange information and values; and (iv) both parties reach shared agreement about the treatment decision(s) made. SDM decreases the asymmetry of information and authority between doctors and patients and empowers patients to take control over their treatment decisions.21

At present, there is much interest in the development of strategies and tools to promote and facilitate SDM. The National Health Service (NHS) in England has recently adopted responsibility for the integration of SDM policies and initiatives in the NHS.22 One of their key objectives is to ‘ensure the NHS becomes dramatically better at involving patients and their carers, and empowering them to manage and make decisions about their own care and treatment’.22 The importance of SDM has been equally heralded in the United States following the passing of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act in 201023 which authorized the development of SDM programmes to ‘help beneficiaries…make more informed treatment decisions based on an understanding of available options, and each patient's circumstances, beliefs and preferences’.24

With regard to ADHD and its management, strong emphasis has been placed on the importance of family involvement in decision making.25, 26, 27 Fiks et al.15 highlighted that although parents of children with ADHD and their clinicians view SDM favourably, more work needs to be done to facilitate SDM during consultations. The use of question prompt lists (QPLs), which contain structured lists of disease and treatment‐specific questions that patients may choose to ask their physicians, may assist in addressing this issue. QPLs are designed to encourage patients to ask questions during consultations with the clinicians involved in their care and in this way, to enhance communication and foster SDM.

Question prompt lists have primarily been utilized in oncology and palliative care settings where they have proven to be inexpensive and effective facilitators for communication between patients, their carers and clinicians.28, 29 The concept of QPLs has also been utilized in other disease states such as diabetes and trialled with parents of children with neurological problems. Therefore, QPLs may prove useful in empowering parents of children with ADHD to source relevant information from HCPs involved in their child's care, especially as they are regarded as a reliable source of information.13, 14 Importantly, utilizing this tool would address parents’ desire to use written resources as a prompt for communication with their child's HCP and the inability of some parents to ask the right questions during consultations.14, 17, 18 Parents would also be able to use the QPL to source information from clinicians that is relevant to their child's needs at a specific point in time and that can be updated over time.14

Therefore, this study aimed to: (i) develop a QPL for parents of children with ADHD intended for use during consultations with clinicians involved in the care of their child and (ii) reach consensus between key stakeholders about its content using Delphi methodology.

Methods

The Delphi technique has been used extensively in health research to establish consensus between groups of experts about a range of issues30 and has led to the development of a number of widely accepted health guidelines and statements.31, 32, 33, 34 It is a completely anonymous process which involves expert participants rating the extent of their agreement with a series of statements over the course of multiple survey rounds distributed by mail or email. By ensuring the participants’ anonymity from the remaining participants, opinions can be expressed freely and it is less likely that a few influential participants can have a disproportionate impact on survey outcomes. The absence of an obligation for the participating experts to meet face‐to‐face also affords researchers the opportunity to recruit experts regardless of their geographical location, clinical background and without constraints on their number. Between surveys, participants are provided with anonymous and summarized information about how the remaining experts rated certain statements and given the opportunity to compare this with their existing rating. This is followed by a subsequent survey in which statements are re‐rated in an attempt to decrease the range of answers and have the experts reach a point of consensus about the presented statements.35 The Delphi method is particularly useful in areas where full scientific knowledge is lacking,36 and as no research has previously been conducted to develop or validate the content of a QPL for ADHD, the researchers felt this would be the most appropriate method to employ in the current investigation. The merit of utilizing a Delphi approach to examine this particular topic is also supported by its suitability in allowing the establishment of consensus about particularly controversial issues. Given the continuing controversies surrounding ADHD and its treatment, we anticipated that key stakeholders were likely to have diverging views and opinions about the importance and relevance of the questions to be included in the QPL and that the Delphi method would be appropriate in light of this.

This study was comprised of two main phases: the development of the QPL content through thematic analysis of existing resources; followed by the Delphi process to reach consensus between expert panel members about the appropriateness, relevance and importance of the QPL content. For this study, the researchers felt it would be essential to consult the following groups in the Delphi process: clinicians involved in the diagnosis and management of ADHD; researchers and academics in the field; parents of children with ADHD; and ADHD consumer advocates. This study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee at the University of Sydney.

QPL development

The QPL content was developed in accordance with guidelines for producing written health‐care interventions and information aids37, 38, 39 and using a similar approach to Langbecker et al.40 The content of the QPL was derived from: (i) eight non‐ADHD‐related published QPLs; (ii) 14 readily available information leaflets regarding ADHD and its treatments; (iii) draft Australian guidelines on ADHD produced by The Royal Australasian College of Physicians;41 and (iv) the information needs of parents of children with ADHD.14

The first three resources were thematically content analysed to derive the major QPL topics and relevant questions for inclusion. The final resource contained focus group findings on the information needs of parents of children with ADHD.14 Questions were derived from the findings of this study, reflecting the range of unanswered questions that participating parents still had, although the questions were paraphrased to simplify language and clarify meaning. These questions were supplemented with additional questions derived from the thematic analysis and were categorized under their respective themes and ultimate QPL topics.

Thematic analysis

Thematic analysis is a commonly used method for the elucidation, analysis and reporting of themes within qualitative data.42, 43, 44, 45 Thematic analysis of the above resources was performed using the systematic approach delineated by Braun and Clark.43 The process involved five distinct phases of analysis: (i) familiarization with the content of the resources; (ii) generation of initial codes; (iii) searching for themes; (iv) reviewing themes; and (v) defining themes.43 Although these phases suggest a linear approach to the analysis, in practice, the process was far more recursive, involving a back and forth movement between the phases to ensure accuracy of the derived themes and subthemes for each resource examined. The analysis was conducted by RA and followed by discussion with PA to ensure the relevance and accuracy of the derived themes and subthemes.

Question prompt list content

Overall, eight themes and six subthemes were identified through the thematic analysis (Table 1). These themes formed the main topics of the draft QPL and questions were written for each theme, a total of 111 questions. The questions were written in line with the recommendations provided by the Centre for Disease Control and Prevention for producing easy‐to‐understand health‐care materials:46 using simple language, avoiding the use of medical terminology (where appropriate) and using short sentences. An overview of the QPL topics and their content is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Overview of question prompt list topics and content

| Topic | Sample question |

|---|---|

| Diagnosis | Are there any other tests or investigations that can be done to confirm this diagnosis? |

| Understanding ADHD | Who can develop ADHD and how common is the disorder? |

| Treatment | In your opinion, what treatment or combination of treatments would be the most effective for my child at this time? |

| Medicines | What are the different types of medicines available and what are the main differences between them? |

| Alternative treatments | Are there any non‐medical interventions or therapies that could help my child? |

| Health‐care team | Will you be the main healthcare professional responsible for managing my child's ADHD? |

| Monitoring ADHD | How often will my child and I see you for monitoring or follow up? |

| Managing ADHD | Are there any strategies that I can learn to help my child cope better at school and at home? |

| Future expectations | |

| Approaching adolescence | Will my child ever outgrow his/her ADHD? |

| Health and medicines | Will the dose of my child's medicine need to be changed as he/she grows older? |

| Academic progress | How will ADHD affect my child's learning and academic performance? |

| Social progress | How will ADHD affect my child's social progress and ability to form friendships? |

| Support and information | Who can I talk to if I feel that I'm not coping well with my child's ADHD? |

ADHD, attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

Expert panel recruitment

Experts were recruited into one of two panels. The professional panel included practicing ADHD clinicians, ADHD researchers and academics, while the non‐professional panel included parents of children diagnosed with ADHD and ADHD consumer advocates. Panel members were recruited from a number of English‐speaking countries with comparable health systems (Australia, United States, United Kingdom, Canada, New Zealand) to ensure the relevance of the participants’ views.

Purposive sampling was used to recruit clinicians, researchers and consumer advocates through direct email invitations from the researchers. Invited professionals were those who were known to the researchers to have extensive expertise and or publications in the ADHD field. We chose to invite paediatricians, clinical psychologists and psychiatrists, as they are the key clinicians involved in ADHD diagnosis and management as outlined in international treatment guidelines for the disorder.25, 26, 27 Consumer advocates contacted were those who were authors of books or online resources for parents, well‐known speakers on ADHD and had documented experience in advocacy roles. Parents were recruited through ADHD support groups, whereby the support groups forwarded the study information to their members, requesting them to contact the researchers if interested. The main study inclusion criterion was that parents had to have one or more children with a current ADHD diagnosis. All subjects who agreed to participate in the study were also invited to nominate any colleagues or contacts who they felt could act as appropriate panel members.

A total of 92 direct email invitations were initially sent to clinicians, researchers and consumer advocates, and a further five emails were sent to ADHD support groups. It is difficult to report with certainty whether all of these invitations were received due to possible errors in the email addresses used and email filtering programs. However, 28 professionals agreed to participate in the study, and one ADHD support group agreed to distribute the study information to its members. Some professionals expressed interest in participating but cited issues such as time and no longer practicing in the field, as barriers to their involvement. Only one support group declined to pass on the study information and the remainder did not respond to the researchers.

Overall, the professional panel included a total of 28 experts consisting of 14 paediatricians, five psychologists/clinical psychologists, five child and adolescent psychiatrists and four researchers and academics (Table 2). The non‐professional panel included eight parents, two of whom were also consumer advocates (Table 2). While there is no recommended sample size for Delphi studies,36 this sample size conforms to that used in previous studies.32, 47, 48

Table 2.

Overview of panel member characteristics

| Paediatricians | Psychologists | Psychiatrists | Researchers/academics | Parents | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 14 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 8a |

| Age | 52 (39–70) | 38 (27–58) | 56 (47–66) | 56 (41–68) | 46 (37–59) |

| Years in practice | 24 (4–43) | 12 (3–25) | 28 (23–33) | 15 (4–25) | 12 (6–30)b |

| Location | |||||

| Australia | 7 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 7 |

| USA | 3 | 1 | 1 | – | 1 |

| UK | 4 | – | – | 1 | – |

| Canada | – | – | 1 | 1 | – |

| New Zealand | – | – | 1 | – | – |

Includes two consumer advocates.

Mean age of children with attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

The Delphi process

To ascertain the panellists’ views about the QPL content and to reach consensus between them, the 111 questions derived from the thematic analysis were entered into an online survey hosted on the SurveyMonkey® website. Using an online survey had many advantages. Participants could access the survey using any electronic device at their own convenience and could choose to submit their responses over several sittings without the risk of losing submitted responses. Furthermore, the researchers were able to collate survey responses promptly and consequently distribute feedback and subsequent surveys to panel members with minimal delay. The survey was set up in a way to ensure that a response to each question was mandatory, which minimized instances of missing data and potential complications during response analysis. Further, through the online survey, the researchers were able to keep track of which panel members were yet to submit their responses and could send reminders accordingly.

The 111 QPL questions were categorized according to their respective QPL topics and each one presented to the panel members on a five‐point scale which included the following options: ‘Essential’, ‘Important’, ‘Dont know/Depends’, ‘Unimportant’ and ‘Should not be included’. This scale has been used in a number of previous Delphi studies.32, 47, 48, 49 Panel members were asked to rate the importance of each question by selecting one of the five options. Space was provided after each question for panellists to comment on the wording of the question or to make other suggestions, including the addition of new questions.

Upon completion of the first survey by all panellists, responses were collated to determine the level of consensus between the professional and non‐professional panels. Depending on the level of consensus, questions were (i) accepted for inclusion in the QPL; (ii) presented to the panellists in a subsequent survey for re‐rating; or (iii) excluded from the QPL according to specific cut‐off values utilized in previous Delphi studies.32, 47, 48, 49 Accepted questions were those which were rated as ‘Essential’ or ‘Important’ by 80% or more of both panels. If a question was rated as ‘Essential’ or ‘Important’ by 80% of only one panel or by 70–80% of both, it was deemed to have a moderate level of consensus and was presented to panel members in a subsequent survey round for re‐rating. Questions that did not satisfy either of these criteria were deemed to have a low level of consensus or support from the panellists and were consequently removed from the QPL. These questions were not presented for re‐rating as previous research has shown it is unlikely for consensus to be reached about these items in subsequent survey rounds.47

All open‐ended feedback provided by panel members following the first survey was also reviewed. This included requests to have certain questions re‐worded or to include new questions in the QPL, which were discussed amongst the study authors until a point of consensus was reached. Questions were re‐worded only when the researchers felt this would enhance parents’ understanding without affecting the intended meaning and purpose of the question. The addition of new questions as suggested by the panellists was only completed if the researchers felt that they addressed new and important issues. Any re‐worded or new questions were presented for re‐rating by panellists in the subsequent survey.

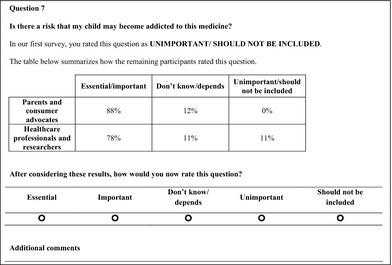

Prior to the distribution of the second survey, each panel member was emailed summarized information about the results of the first survey round. The information highlighted the included and excluded questions and those that the panellists would be asked to re‐rate in the second survey. The second survey included all questions which met criteria for re‐rating from the first survey round, questions that were re‐worded and any new questions. Questions that required re‐rating were presented to panel members alongside a table that summarized how the two panels rated that question in the first survey round (Fig. 1). Therefore, the second round of the Delphi process involved the development of individualized surveys for each panel member for re‐rated questions. In this way, the panel members could decide whether to change their existing rating or to maintain their response.

Figure 1.

Sample feedback table provided to panellists during follow‐up surveys where questions required re‐rating.

Responses to the second survey round were collated and QPL questions were included, excluded or placed aside for re‐rating in a third survey using the same criteria used after the first survey round. The third survey round only included: (i) those new questions presented to the panellists in the second survey round which met criteria for re‐rating; (ii) any questions the panellists asked to be re‐worded; and (iii) new QPL questions suggested by the panellists after the second survey round. Individualized surveys were again developed for the third survey round and feedback provided to the panellists in the same way used in the second survey round. This survey and response analysis process was continued until all QPL items met either inclusion or exclusion criteria and no new suggestions were raised by the panel members. This was achieved at the conclusion of the third survey.

Feedback from panel members

To assess the panel members’ satisfaction with the concept of a QPL for parents of children with ADHD and with the Delphi method used, panellists were asked to complete an optional online feedback survey at the conclusion of the study. The feedback survey contained 24 statements relating to the panellists’ views about the concept and structure of the QPL and the Delphi process. These statements were adapted from previous studies.32, 49 Panel members were asked to respond to these statements by selecting one of five options along a five‐point agreement scale ranging from ‘Strongly Agree’ to ‘Strongly Disagree’.

Results

Expert panel members

Thirty‐six panel members participated in the Delphi study and were recruited from Australia (n = 22), United States (n = 6), United Kingdom (n = 5), Canada (n = 2) and New Zealand (n = 1). There was a high panel member retention rate across the three survey rounds. All members of the non‐professional panel participated in the three survey rounds, while five members of the professional panel did not complete the second or third surveys.

Delphi survey outcomes

A total of 122 QPL questions were presented to the panel members for rating across the three survey rounds. These included the initial 111 questions developed by the researchers and an additional 11 new questions which were developed based on the panellists’ feedback from the first survey round. Figure 2 outlines the number of items that were accepted, rejected or re‐rated in each of the three survey rounds. The initial QPL topics remained unchanged with the exception of the treatment section which was divided into three distinct subtopics: (i) medicines, (ii) psychological and (iii) alternative.

Figure 2.

Questions accepted, rejected and re‐rated during each Delphi survey round.

In total, 88 (72%) of the 122 questions presented to panel members for rating across the three survey rounds met the consensus criteria required for inclusion (Appendix 1). A total of 34 (28%) of the 122 questions presented were excluded from the QPL (Appendix 2). Across the three survey rounds, only six questions were rejected with strong consensus (after the first survey round), where 50% or more of the members of both panels rated a question as ‘Unimportant’ or ‘Should not be included’ (Appendix 2).

Utilizing Rosenthal's classification of effect size for differences in percentages within social science research data,50 we were able to identify those questions about which there was significant disagreement, as utilized in previous Delphi research.34 This categorization associated a medium effect size with a difference of at least 18% and a large effect size with a difference of at least 30% between the two groups in question.50 Panellists’ responses to 7 (20.6%) of the 34 excluded questions were associated with medium and large group differences. These questions are presented in Table 3 and highlight the areas where consensus between the professional and non‐professional panels was difficult to establish.

Table 3.

Examples of disagreement between the professional and non–professional panels that contributed to questions being excluded

| Rejected question | (1) Non‐professional panel endorseda (%) | (2) Professional panel endorseda(%) | Difference 1 and 2 (%)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| What do these tests involve?c | 87.5 | 56.5 | 31 |

| Are there any vitamin supplements that can help my child? | 75 | 39.3 | 35 |

| Are there any supplements that I should avoid giving to my child? | 87.5 | 43.5 | 44 |

| Can I get this medicine from my usual pharmacy? | 87.5 | 60.9 | 26.6 |

| What government services can I access to help my child? | 100 | 65.2 | 34.8 |

| What should I do or who can I contact if I am concerned about any of these changes?d | 100 | 73.9 | 26.1 |

| How much will appointments cost? | 87.5 | 52.2 | 35.3 |

Question rated as ‘Essential’/’Important’ for inclusion in the question prompt list (QPL).

Differences between the endorsement of the professional and non‐professional panel used to identify questions about which there was significant disagreement according to Rosenthal's classification61 where medium effect size shown by a difference of at least 18% and large effect size shown by a difference of ≥30%.

This question was presented to the panellists as a follow‐up to the accepted question ‘Are there any other tests or investigations that can be done to confirm this diagnosis?’

This question was presented to the panellists as a follow‐up to the accepted question ‘During adolescence, will the ADHD symptoms change?’

Panel member feedback

Of the 31 participants who completed the final survey, 18 (58%) completed the optional feedback survey. Feedback was overwhelmingly positive, both with regard to the concept and structure of the QPL, and the Delphi research process (Table 4). All (100%) respondents either strongly agreed or agreed with the statement ‘I thought the QPL used appropriate language which can be easily understood by parents and carers of children with ADHD’. Further, 94% responded with either ‘Agree’ or ‘Strongly Agree’ to the statement ‘I believe the QPL will encourage discussion between parents of children with ADHD and healthcare professionals’ and 88% responded similarly to the statement ‘I would recommend the QPL to other parents or healthcare professionals’.

Table 4.

Panel member responses to feedback survey statements

| Feedback statement | Strongly agree | Agree | Neither | Disagree | Strongly disagree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concept and content of the QPL | |||||

| I thought the questions in the QPL were easy to follow | 22.2 | 72.2 | 5.5 | 0 | 0 |

| I thought the QPL was too long | 0 | 22.2 | 44.4 | 33.3 | 0 |

| I thought the QPL used appropriate language which can be easily understood by parents and carers of children with ADHD | 11.1 | 88.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| I thought the QPL covered questions that are relevant to parents and carers of children with ADHD | 44.4 | 50 | 5.5 | 0 | 0 |

| I thought the language used in the QPL was too clinical for use by parents and carers of children with ADHD | 0 | 11.1 | 5.5 | 77.7 | 5.5 |

| I believe the QPL will benefit parents and carers of children with ADHD | 22.2 | 72.2 | 5.5 | 0 | 0 |

| I believe the QPL will encourage discussion between parents of children with ADHD and healthcare professionals | 16.6 | 72.2 | 11.1 | 0 | 0 |

| I would recommend the QPL to other parents or healthcare professionals | 16.6 | 72.2 | 11.1 | 0 | 0 |

| The Delphi research process | |||||

| I thought the participation of healthcare professionals in this study was important | 55.5 | 44.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| I thought the participation of researchers in this study was important | 50 | 33.3 | 16.6 | 0 | 0 |

| I thought the participation of parents in this study was important | 72.2 | 27.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| I thought the participation of ADHD consumer advocates in this study was important | 33.3 | 61.1 | 5.5 | 0 | 0 |

| I thought the use of emails was an appropriate way to be contacted by the researchers | 61.1 | 38.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| I thought the use of online surveys was a good way to collect data and feedback | 61.1 | 38.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| I thought the online surveys were clear and easy to follow | 44.4 | 55.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| I thought the summary information provided by the researchers about the results of each round was important | 33.3 | 66.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| I thought the instructions for the two follow‐up surveys were clear and easy to follow | 22.2 | 88.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| I thought the summary tables provided in follow‐up surveys for the questions to be re‐rated were useful | 27.7 | 61.1 | 5.5 | 0 | 0 |

| I would recommend the Delphi method for other research projects about ADHD | 22.2 | 66.6 | 11.1 | 0 | 0 |

| I believe the Delphi process can be of benefit to the development of QPLs for other medical conditions | 16.6 | 72.2 | 11.1 | 0 | 0 |

| I thought the time commitment was appropriate for this study | 22.2 | 77.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| I believe the remuneration is appropriate | 16.6 | 61.1 | 16.6 | 5.5 | 0 |

| I thought that participating in this research was worthwhile | 55.5 | 44.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| I enjoyed participating in this Delphi study | 55.5 | 38.8 | 5.5 | 0 | 0 |

ADHD, attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder; QPL, question prompt list.

All respondents were in agreement with statements relating to the online surveys being a good way of collecting data and feedback, the clarity of the online surveys, the usefulness of feedback provided to the panellists between survey rounds and the appropriateness of the time commitment for the study. All respondents strongly agreed or agreed with the statement ‘I thought that participating in this research was worthwhile’ and 88.8% provided similar ratings to the statement ‘I believe the Delphi process can be of benefit to the development of other QPLs for other medical conditions’.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first time that the Delphi method has been used to systematically develop and validate the content of any QPL by developing consensus amongst HCPs, researchers, parents and consumer advocates regarding its content. It is also the first time that a QPL has been developed with the aim of addressing the information needs of parents of children with ADHD. Although significant breakthroughs have been made in ADHD research over recent years,51 there remains a degree of uncertainty regarding its aetiology52 and much controversy surrounding its management especially using pharmacotherapy.53, 54 It is for this reason that the Delphi method was chosen as it was anticipated that key stakeholders were likely to have differing opinions about the importance and relevance of various ADHD‐related topics and the method has been demonstrated to be effective in achieving consensus about particularly controversial topics.55

During the three survey rounds conducted in this Delphi study, 88 (72%) of the total 122 questions presented to the panellists for rating were accepted for inclusion. In a previous Delphi study conducted to develop mental health first aid guidelines and which used the same method and criteria for item consensus, 40.6% of the total 335 statements presented to the panellists were accepted.47 While it may be difficult to make direct comparisons between these studies, the high acceptance rate of questions for the QPL in the current study cannot be discounted. This may be attributed to the rigour of the thematic analysis procedures used in the development of the QPL content and reference to qualitative data from our earlier work,14 which allowed the researchers to derive questions that were of relevance and importance to the participating stakeholders.

The two follow‐up surveys used in the current study required panellists to re‐rate 39 questions that had not met inclusion criteria after first being presented to the panel members. Of these, 29 (74%) were subsequently accepted for inclusion in the QPL, which demonstrates the value of the Delphi process and the provision of group summary information. This highlights the fact that panellists gave due consideration to the opinions of the range of stakeholders involved in the study and that while some questions may not have been deemed to be important or relevant to one panel member, they were to others.

The final 88 questions, spanning eight major topics, have been formatted into an A5 booklet titled ‘Asking questions about ADHD: Questions to ask your child's healthcare provider about ADHD and its treatment’. The booklet lists the questions according to their respective topics and provides space after each topic for parents/carers to write down their own questions or responses provided by the clinician. The booklet contains instructions for use, which emphasize that the booklet does not cover all possible questions that the parents/carers may wish to ask their clinicians, and encourage them to think of any further questions that may not be listed and they would like responses to. The instructions also advise parents/carers against asking all 88 questions during one consultation, but rather to take their time to read through the booklet and to identify those questions that may be relevant to their child's needs at that specific point in time.

In this way, the booklet is intended to be used by parents/carers on a long‐term basis and updated over time, as their child's needs change with age. We believe that the booklet will be of most benefit to parents of children who have been referred onto a specialist for a potential diagnosis of ADHD, or those who have recently been diagnosed. As ADHD is most commonly diagnosed around the age of 8 or 9, although children as young as 3 have been diagnosed, we anticipate that the content of the QPL will be of most relevance to parents of children and young teens (3–14 years) and that its use will extend into the late teens and early adulthood.

The Delphi procedure used in this study not only allowed the researchers to identify those questions about which there was a high level of consensus, but also those where there was significant disagreement between the professional and non‐professional panel. The significance of the differences in panel ratings for the excluded questions were categorized according to Rosenthal's classification of effect size for percentage differences within social science research data.50 There were seven questions where medium and large effect size differences in panel ratings were observed (Table 3).

Members of the professional panel expressed that some of these questions were potentially redundant or repetitive. For example, clinicians felt that a response to the question ‘What do these tests involve?’ would be provided to the (accepted) question which immediately preceded it ‘Are there any other tests or investigations that can be done to confirm this diagnosis?’. The same sentiment was expressed regarding the question ‘What should I do or who can I contact if I am concerned about any of these changes?’ which was a follow‐up to the (accepted) question ‘During adolescence, will the ADHD symptoms change?’. However, the strong endorsement of these follow‐up questions by the non‐professional panel may be suggestive of parents’ desire to get as much information as possible from the clinician and may be reflective of difficulties they may have experienced in sourcing information from clinicians in the past as demonstrated by the findings of our previous research.14

It is worth drawing attention to some of the remaining questions, however, as the significant disagreement between the professional and non‐professional panels may point towards deeper issues or be indicative of areas of deficiency in the ADHD literature. For example, the question ‘Are there any vitamin supplements that can help my child?’ was endorsed by 75% of the non‐professional panel compared to only 39.3% of the professional panel. Sources in the literature suggest that the role of vitamins in the management of ADHD symptoms is limited.56, 57 In a review of the efficacy of nutrient supplementation for the treatment of ADHD, Rucklidge et al.56 highlight that evidence in this area is sparse and that while positive responses to zinc supplementation have been observed in two randomized controlled trials, evidence surrounding other supplements including essential fatty acids and vitamins is mixed and requires further investigation. It is likely that the professional panel did not endorse this particular question in light of the lack of evidence for the efficacy of such supplements. However, the non‐professional panel's support of this question is expected as parents of children with ADHD have great interest in exploring alternative and particularly, non‐pharmacological, options for ADHD management.58, 59 This stems from the negative portrayal of medications by the media and public opinion and concerns surrounding the potential side‐effects of these agents.6, 8, 9 It is possible that information relating to the lack of efficacy of vitamin supplementation needs to be better disseminated to parents.

Another question which was excluded due to significant disagreement between the two panels was: ‘What government services can I access to help my child?’. All members of the non‐professional panel endorsed this question compared to only 65.2% of the professional panel. The non‐professional panel's support for this question is in line with the findings of our previous work which highlighted that parents have a strong desire to learn more about the availability of government services to assist them with the management of their child's ADHD.14 This is also consistent with research that indicates parents often do not know what type of services they may be able to access for this purpose.60 It is unclear why the professional panel did not endorse this question to the same degree, although this may suggest that greater awareness needs to be raised amongst clinicians regarding the importance of explaining the avenues of assistance available to parents.

Limitations

The findings of this study should be viewed in the light of a few limitations. Compared to the size of the professional panel (n = 28), the size of the non‐professional panel (n = 8) was small, though similar to non‐professional panels in previous Delphi studies.47, 48 Only one support group responded positively to participation. The remaining groups did not provide a response with the exception of one, which did not agree to distribute the study information. In conducting this Delphi study, survey links were distributed to participants at the same time and responses collected by a set date so as not to prolong the time between surveys and to ensure prompt collation and analysis of the panellists’ responses for the generation of subsequent surveys. As a result, it was difficult to modify the recruitment strategy used to identify parents for participation, without the risk of negatively impacting upon the Delphi process.

Further, panellists were only recruited from English‐speaking countries with comparable health systems. Therefore, the content of the QPL may not be generalizable to parents/carers of children with ADHD and ADHD clinicians in other countries.

A potential limitation of conducting this Delphi study online is that panel members could not directly discuss any concerns or exchange opinions with other panellists. The nominal group technique, for example, involves the provision of study surveys to panel members during structured meetings at a designated venue.61 In this way, panellists have an opportunity for face‐to‐face discussion during which they can raise any concerns or clarify any issues they may have. However, it is possible that in this setting panel members’ opinions may be affected by the dominance of certain individuals. The approach used in this study is advantageous in that the researchers facilitated discussion between panel members through the feedback provided at the conclusion of each round, highlighting any concerns or recommendations made by other participants in an anonymous fashion.

Conclusions

In this study, the researchers were able to develop an ADHD‐specific QPL through a systematic examination of existing ADHD and QPL resources and drawing on the findings of previous work regarding the information needs of parents of children with ADHD.14 The use of a Delphi process provided a structured way to achieve consensus between HCPs, researchers, parents and consumer advocates about the content of the QPL. To our knowledge, this is the first demonstration of the utility of the Delphi method in the validation of the content of any QPL. The feedback provided by the panellists demonstrated overwhelmingly positive support for the concept and content of the QPL as well as using the Delphi process to achieve consensus about the QPL content. The QPL booklet (containing the 88 questions) has been evaluated by a further 20 parents and carers of children with ADHD using established user testing methods62 to ensure that the QPL contains readable and understandable information that can be used by this group.63 We are currently conducting a pilot study to determine the feasibility of QPL provision in clinical environments and its impact on a number of parent and clinician related outcomes. The development of an ADHD‐specific QPL is a move towards empowering parents to ask questions about their child's ADHD and increasing their involvement in shared treatment decision making.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship or publication of this article.

Conflict of interests

The authors have no conflict of interests related to any aspect of this research.

Appendix 1. Questions accepted for inclusion in the question prompt list

| Topic | Question | Round |

|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | What is the name of my child's condition? | 1 |

| How is ADHD diagnosed? | 1 | |

| Does my child need to have any educational or psychological tests? | 1 | |

| Are there any other tests or investigations that can be done to confirm this diagnosis? | 2 | |

| I'm not sure how to tell my child or my family about this diagnosis‐ how can I explain it to them? | 1 | |

| Understanding ADHD | What is ADHD? | 1 |

| What are the main signs/symptoms of ADHD? | 1 | |

| Who can develop ADHD and how common is the disorder? | 1 | |

| What causes ADHD? | 1 | |

| What will happen if ADHD is left untreated? | 1 | |

| Will ADHD affect my child's learning? | 2 | |

| How does my parenting style affect my child's ADHD? | 3 | |

| Treatment | What treatment options are available for ADHD? | 1 |

| Other than using medicines, what else can be done to treat ADHD? | 1 | |

| Does my child need to be treated straight away? | 2 | |

| In your opinion, what treatment or combination of treatments would be the most effective for my child at this time? | 1 | |

| Do I have to make a decision about treatment now, or can I talk to other healthcare professionals about my child's treatment, even if I want my child to stay with you for treatment? | 1 | |

| Medicines | What are the different types of medicines available and what are the main differences between them? | 1 |

| What is the name of the medicine you're recommending for my child? | 1 | |

| How will this medicine help my child? | 1 | |

| Is this medicine a cure for ADHD? | 1 | |

| How will this medicine make my child feel? | 1 | |

| When should I expect to see an improvement in my child's symptoms? | 1 | |

| How will I know that the medicine is working? | 1 | |

| What if no improvement is seen in my child's symptoms while on this medicine? | 1 | |

| How long does my child need to take this medicine? | 1 | |

| Will my child need to take this medicine even as a teenager or a young adult? | 2 | |

| Are there any tests required before my child starts to take this medicine? | 2 | |

| How is the medicine taken and how often? | 1 | |

| When should I start to give this medicine to my child? | 1 | |

| Can my child have breaks from the medicine, for example during school breaks and on weekends? | 1 | |

| What are the most common side effects of this medicine? | 1 | |

| What are the long term side effects of this medicine? | 1 | |

| Are there any serious or life‐threatening side effects associated with this medicine? | 1 | |

| What should I do if my child experiences any side effects? | 1 | |

| Is there a risk that my child may become addicted to this medicine? | 2 | |

| Will this medicine affect my child's growth? | 1 | |

| Which non‐prescription medicines or supplements interfere with this medicine? | 1 | |

| What are the likely costs of this medicine? | 1 | |

| How do I explain to my child why he/she needs medicine? | 1 | |

| Will the script for this medicine be processed or handled any differently from other scripts when I go to my pharmacy? | 3 | |

| Psychological treatments | Can you recommend any psychological treatments to help my child? | 2 |

| What will this treatment involve? | 2 | |

| How will this treatment help my child's ADHD symptoms compared to treatment using medicines? | 2 | |

| Does my child need to start this treatment straight away? | 3 | |

| How long will my child need to use this treatment? | 3 | |

| When can I expect to see an improvement in my child's ADHD symptoms using this treatment? | 2 | |

| How will my child's progress on this treatment be monitored? | 2 | |

| Will you be responsible for administering this treatment, or would you recommend that my child and I visit another healthcare professional to help us with this? | 3 | |

| Alternative treatments | Are there any non‐medical interventions or therapies that could help my child? | 3 |

| What other treatments or activities are there that I could use to help my child? | 1 | |

| Are there any sports or activities that can help my child's ADHD? | 2 | |

| Health‐care team | Will you be the main healthcare professional responsible for managing my child's ADHD? | 2 |

| Are there any other health care professionals that I should involve in the management of my child's ADHD? | 2 | |

| Will I need to visit you when my child needs a new script or can I visit our family doctor for this? | 2 | |

| What other healthcare services are available for my child? | 1 | |

| Do I need a referral to access these services? | 1 | |

| Will you contact my child's GP to discuss my child's condition and treatment? | 1 | |

| Who should I contact if I have questions about my child's treatment? Are you my first point of call? | 1 | |

| When should my child and I visit you again? | 1 | |

| Monitoring ADHD | What will you be monitoring while my child is undergoing treatment? | 1 |

| What should I be monitoring while my child is on this medicine? | 1 | |

| How often will my child and see you for monitoring or follow up? | 1 | |

| How will you assess my child's progress? | 1 | |

| What are some ways that I can identify changes in my child's behaviour or mood? | 2 | |

| When should I expect these changes to happen with respect to the timing of my child's medication dose? | 3 | |

| Managing ADHD | Are there any strategies that I can learn to help my child cope better at school and at home? | 2 |

| What should I tell the staff at my child's school about my child's condition and treatment? | 1 | |

| What can the school do to help my child? | 1 | |

| What educational interventions or services can I access to help my child? | 1 | |

| Who should I speak to if I'm concerned about my child's academic or social progress? | 1 | |

| Future expectations | ||

| Approaching adolescence | Will my child ever outgrow his/her ADHD? | 1 |

| How will ADHD affect my child as he/she approaches adolescence (10–19 years of age)? | 1 | |

| During adolescence, will my child's ADHD symptoms change? | 2 | |

| If so, what differences can I expect to see? | 2 | |

| How can I help my child cope with these changes? | 2 | |

| Health and medicines | Will I need to tell you about any new medicines my child takes in the future? | 1 |

| Will the dose of my child's medicine need to be changed as he/she grows older? | 1 | |

| Academic progress | How will ADHD affect my child's learning and academic performance? | 1 |

| How will the medicine my child is taking affect my child's learning and academic performance? | 1 | |

| Social progress | How will ADHD affect my child's social progress and ability to form friendships? | 1 |

| How will the medicine my child is taking affect my child's social development? | 1 | |

| Support and information | Who should I speak to if I receive any conflicting information or advice? | 1 |

| Who can I talk to if I feel that I'm not coping well with my child's ADHD? | 1 | |

| Is there a local support group that I can attend? What are the contact details? | 1 | |

| Is there any written information about ADHD that you could provide me with? | 2 | |

| Can you recommend any trustworthy websites about ADHD and its treatment? | 2 | |

| Will I get any refunds from Medicare? | 1 | |

Appendix 2. Questions excluded from the question prompt list

| Topic | Question | Round |

|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | Which type of ADHD does my child have? | 1 |

| Are brain scans effective in identifying ADHD? | 1 | |

| What do these tests involve? | 2 | |

| Understanding ADHD | Is there a possibility that I may have ADHD as well? | 1 |

| Is there a possibility that my other children may also be affected by ADHD? | 3 | |

| Treatment | ||

| Medicines | Does this medicine increase the risk of my child becoming addicted to other drugs later in life? | 2 |

| What will these tests involve? | 2 | |

| Is this medicine generally available in local pharmacies? | 3 | |

| Psychological treatments | No questions excluded from QPL. | |

| Alternative treatments | Are there any vitamin supplements that can help my child? | 1 |

| Are there any supplements that I should avoid giving to my child? | 2 | |

| Health‐care team | No questions excluded from QPL. | |

| Monitoring ADHD | How can I deal with these changes? | 1 |

| Should I keep written records of my child's symptoms or medication progress? | 1 | |

| If so, how should I do this? | 1 | |

| Will you need to do any tests? | 2 | |

| Managing ADHD | How does diet affect ADHD? | 1 |

| Are there any foods or drinks that I should avoid giving to my child to help reduce his/her symptoms? | 1 | |

| Where can I get information about this training? | 1 | |

| What government services can I access to help my child? | 2 | |

| With my consent, will you be contacting the staff from my child's school to let them know about my child's condition? | 2 | |

| Future expectations | ||

| Approaching adolescence | What should I do or who can I contact if I am concerned about any of these changes? | 2 |

| Health and medicines | Will ADHD increase the risk of my child developing other medical conditions? | 1 |

| Will I need to monitor this and if so, how should I do this?a | 1 | |

| What if my child develops another medical condition in the future? How will this affect his/her ADHD and medicine?a | 1 | |

| Will ADHD or the medicines used to treat it affect my child's ability to drive in the future? | 1 | |

| Academic progress | How will ADHD impact on my child's future career choices? | 1 |

| How can I found out more about the major academic milestones of a developing child?a | 1 | |

| Can you help me write some short and long term academic goals for my child so I can keep track of how well my child is progressing with his/her learning?a | 1 | |

| Social progress | Can you help me write some short and long term social goals for my child so I can keep track of how well my child is developing socially?a | 1 |

| Support and information | What are the details of online support services that I can use? | 1 |

| Can you put me in touch with other parents who have been through this? | 1 | |

| Do you have information I can give my family and friends if they ask me about ADHD? | 1 | |

| Do you have information in other languages? | 2 | |

| How much will appointments cost? | 2 | |

| Is there anyone I can speak to about financial matters such as costs of treatment and appointment fees?a | 1 | |

Questions rejected with a strong level of consensus after the first survey round.

References

- 1. Polanczyk G, de Lima MS, Horta BL, Biederman J, Rohde LA. The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: a systematic review and metaregression analysis. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 2007; 164: 942–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Biederman J, Monuteaux MC, Doyle AE et al Impact of executive function deficits and attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) on academic outcomes in children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 2004; 72: 757–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. De Boo GM, Prins PJM. Social incompetence in children with ADHD: possible moderators and mediators in social‐skills training. Clinical Psychology Review, 2007; 27: 78–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Curatolo P, Paloscia C, D'Agati E, Moavero R, Pasini A. The neurobiology of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. European Journal of Paediatric Neurology, 2009; 13: 299–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hinshaw SP. The stigmatization of mental illness in children and parents: Developmental issues, family concerns and research needs. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 2005; 46: 714–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. McLeod JD, Fettes DL, Jensen PS, Pescosolido BA, Martin JK. Public knowledge, beliefs and treatment preferences concerning attention‐deficit hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D. C.), 2007; 58: 626–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ahmed R, McCaffery KJ, Aslani P. Factors influencing parental decision making about stimulant treatment for attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 2013; 23: 163–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Barkley RA, McMurray MB, Edelbrock CS, Robins K. Side effects of methylphenidate in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a systemic, placebo‐controlled evaluation. Pediatrics, 1990; 86: 184–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Efron D, Jarman F, Barker M. Side effects of methylphenidate and dexamphetamine in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a double‐blind crossover trial. Pediatrics, 1997; 100: 662–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Daley D. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a review of the essential facts. Child: Care, Health and Development, 2006; 32: 193–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Peters K, Jackson D. Mothers’ experiences of parenting a child with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 2009; 65: 62–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ahmed R, Aslani P. Attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder: an update on medication adherence and persistence in children, adolescents and adults. Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research, 2013; 13: 791–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sciberras E, Iyer S, Efron D, Green J. Information needs of parents of children with attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Clinical Pediatrics, 2010; 49: 150–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ahmed R, Borst J, Wei YC, Aslani P. Do parents of children with attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) receive adequate information about the disorder and its treatments? A qualitative investigation. Patient Prefer Adherence, 2014; 8: 661–670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fiks AG, Hughes CC, Gafen A, Guevara JP, Barg FK. Contrasting parents’ and pediatricians’ perspectives on shared decision‐making in ADHD. Pediatrics, 2011; 127: e188–e196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Brook U, Boaz M. Attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder/learning disabilities (ADHD/LD): parental characterization and perception. Patient Education and Counseling, 2005; 57: 96–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Coulter A, Entwistle V, Gilbert D. Sharing decisions with patients: is the information good enough? British Medical Journal, 1999; 318: 318–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hummelinck A, Pollock K. Parents’ information needs about the treatment of their chronically ill child: a qualitative study. Patient Education and Counseling, 2005; 62: 228–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Drotar D, Crawford P, Bonner M. Collaborative decision‐making and promoting treatment adherence in pediatric chronic illness. Patient Intelligence, 2010; 2: 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Shared decision‐making in the medical encounter: what does it mean? (or, it takes at least two to tango). Social Science and Medicine, 1997; 44: 681–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Joosten EAG, DeFuentes‐Merillas L, de Weert GH, Sensky T, van der Staak CPF, de Jong CAJ. Systematic review of the effects of shared decision‐making on patient satisfaction, treatment adherence and health status. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 2008; 77: 219–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. NHS England . Shared decision making [Internet], 2014. Available at: http://www.england.nhs.uk/ourwork/pe/sdm/, accessed 9 May 2014.

- 23. 111th United States Congress . HR 3590: Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. No. 111‐148: 906, 2010.

- 24. Informed Medical Decisions Foundation . Affordable care act [Internet], 2014. Available at: http://www.informedmedicaldecisions.org/shared-decision-making-policy/federal-legislation/affordable-care-act/, accessed May 9 2014.

- 25. Subcommittee on Attention‐Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, Steering Committee on Quality Improvement and Management , Wolraich M, Brown L et al ADHD: clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Pediatrics, 2011; 128: 1007–1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Canadian Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Resource Alliance (CADDRA) . Canadian ADHD Practice Guidelines, 3rd edn Toronto, ON: CADDRA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 27. National Health and Medical Research Council . Clinical Practice Points on the Diagnosis, Assessment and Management of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Children and Adolescents. Canberra, ACT: Australian Government, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Clayton J, Butow P, Tattersall M et al Asking questions can help: development and preliminary evaluation of a question prompt list for palliative care patients. British Journal of Cancer, 2003; 89: 2069–2077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Clayton JM, Butow PN, Tattersall MHN et al Randomized controlled trial of a prompt list to help advanced cancer patients and their caregivers to ask questions about prognosis and end of life care. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2007; 25: 715–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hasson F, Keeney S, McKenna H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 2000; 32: 1008–1015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Langlands RL, Jorm AF, Kelly CM, Kitchener BA. First aid recommendations for psychosis. Using the Delphi method to gain consensus between mental health consumers, carers and clinicians. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 2008; 34: 435–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hart LM, Bourchier SJ, Jorm AF et al Development of mental health first aid guidelines for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people experiencing problems with substance use: a Delphi study. BMC Psychiatry, 2010; 10: 78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Campbell SM, Cantrill JA, Roberts D. Prescribing indicators for UK general practice: Delphi consultation study. British Medical Journal, 2000; 321: 425–428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Berk L, Jorm AF, Kelly CM, Dodd S, Berk M. Development of guidelines for caregivers of people with bipolar disorder: a Delphi expert consensus study. Bipolar Disorders, 2011; 13: 556–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Skulmoski GJ, Hartman FT, Krahn J. The Delphi method for graduate research. Journal of Information Technology Education: Research, 2007; 6: 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Powell C. The Delphi technique: myths and realities. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 2003; 41: 376–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Charnock D, Shepperd S, Needham G, Gann R. DISCERN: an instrument for judging the quality of written consumer health information on treatment choices. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 1999; 53: 105–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Coulter A, Entwistle VA, Gilbert D. Informing Patients: An Assessment of the Quality of Patient Information Materials. London: King's Fund Publishing, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 39. O'Donnell M, Entwistle V. Producing Information About Health and Health Care Interventions: A Practical Guide. University of Aberdeen, 2003. Available at: http://www.abdn.ac.uk/hsru/documents/revisedguide_090603.pdf, accessed 30 November 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Langbecker D, Janda M, Yates P. Development and piloting of a brain tumour‐specific question prompt list. European Journal of Cancer Care, 2012; 21: 517–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. The Royal Australian College of Physicians . Australian Guidelines on Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), 2009. [Cited 2014 Jun 1]. Available from: https://www.racp.edu.au/index.cfm?objectid=393DD54A-04C5-85AC-B35FE82BA4849595 [Google Scholar]

- 42. Aronson J. A pragmatic view of thematic analysis. The Qualitative Report, 1994; 2 [Cited 2014 Jun 1]. Available from: http://www.nova.edu/ssss/QR/BackIssues/QR2-1/aronson.html. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 2006; 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Riessman CK. Narrative Methods for the Human Sciences. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Floersch J, Longhofer JL, Kranke D, Townsend L. Integrating thematic, grounded theory and narrative analysis. A case study of adolescent psychotropic treatment. Qualitative Social Work, 2010; 9: 407–425. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Centers for disease control and prevention . Simply put: A Guide for Creating Easy‐to‐Understand Materials, 3rd edn Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kelly CM, Jorm AF, Kitchener BA. Development of mental health first aid guidelines on how a member of the public can support a person affected by a traumatic event: a Delphi study. BMC Psychiatry, 2010; 10: 49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kelly CM, Jorm AF, Kitchener BA, Langlands RL. Development of mental health first aid guidelines for suicidal ideation and behaviour: a Delphi study. BMC Psychiatry, 2008; 8: 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hart LM, Jorm AF, Kanowski LG, Kelly CM, Langlands RL. Mental health first aid for Indigenous Australians: using Delphi consensus studies to develop guidelines for culturally appropriate responses to mental health problems. BMC Psychiatry, 2009; 9: 47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Rosenthal JA. Qualitative descriptors of strength of association and effect size. Journal of Social Service Research, 1996; 21: 37–59. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Antshel KM, Hargrave TM, Simonescu M, Kaul P, Hendricks K, Faraone SV. Advances in understanding and treating ADHD. BMC Medicine, 2011; 9: 72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Nigg JT. What Causes ADHD? Understanding What Goes Wrong and why. New York: The Guildford Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Stubbe DE. Attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder overview. Historical perspective, current controversies, and future directions. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 2000; 9: 469–479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wilens TE, Biederman J, Spencer TJ. Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder across the lifespan. Annual Review of Medicine, 2002; 53: 113–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Graham B, Regehr G, Wright JG. Delphi as a method to establish consensus for diagnostic criteria. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 2003; 56: 1150–1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Rucklidge JJ, Johnstone J, Kaplan BJ. Nutrient supplementation approaches in the treatment of ADHD. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics, 2009; 9: 461–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Curtis LT, Patel K. Nutritional and environmental approaches to preventing and treating autism and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): a review. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 2008; 14: 79–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Brue AW, Oakland TD. Alternative treatments for attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder: dose evidence support their use? Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine, 2002; 8: 68–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Johnston C, Seipp C, Hommersen P, Hoza B, Fine S. Treatment choices and experiences in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: relations to parents’ beliefs and attributions. Child: Care, Health and Development, 2005; 31: 669–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Sawyer MG, Rey JM, Arney FM, Whitham JK, Clark JJ, Baghurst PA. Use of health and school‐based services in Australia by young people with attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 2004; 43: 1355–1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Jones J, Hunter D. Consensus methods for medical and health services research. British Medical Journal, 1995; 311: 376–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Jay E, Aslani P, Raynor D. User testing of consumer medicine information in Australia. Health Education Journal, 2011; 70: 420–427. [Google Scholar]

- 63. Ahmed R, Raynor DK, McCaffery KJ, Aslani P. The design and user‐testing of a question prompt list for attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder. BMJ Open, 2014; 4: e006585. doi:10.1136/bmjopen‐2014‐006585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]