Abstract

Background

Cancer survivors suffer from long-term adverse effects that reduce health-related quality of life (QOL) and physical functioning, creating an urgent need to develop effective, durable, and disseminable interventions. Harvest for Health, a home-based vegetable gardening intervention, holds promise for these domains.

Methods

This report describes the methods and recruitment experiences from two randomized controlled feasibility trials that employ a waitlist-controlled design. Delivered in partnership with Cooperative Extension Master Gardeners, this intervention provides one-on-one mentorship of cancer survivors in planning and maintaining three seasonal vegetable gardens over 12 months. The primary aim is to determine intervention feasibility and acceptability; secondary aims are to explore effects on objective and subjective measures of diet, physical activity and function, and QOL and examine participant factors associated with potential effects. One trial is conducted exclusively among 82 female breast cancer survivors residing in the Birmingham, AL metropolitan area (BBCS); another broadly throughout Alabama among 46 older cancer survivors aged ≥60 (ASCS).

Results

Response rates were 32.6% (BBCS) and 52.3% (ASCS). Both trials exceeded 80% of their accrual target. Leading reasons for ineligibility were removal of >10 lymph nodes (lymphedema risk factor), lack of physician approval, and unwillingness to be randomized to the waitlist.

Conclusion

To date, recruitment and implementation of Harvest for Health appears feasible.

Discussion

Although both studies encountered recruitment challenges, lessons learned can inform future larger-scale studies. Vegetable gardening interventions are of interest to cancer survivors and may provide opportunities to gain life skills leading to improvements in overall health and QOL.

Keywords: Gardening, Cancer Survivors, Quality of Life, Physical Function, Neoplasms, Diet

Introduction

Currently, there are nearly 14.5 million cancer survivors in the United States [1]. The largest subsets of these survivors are breast cancer survivors (approximately 22% of survivors) and/or survivors over the age of 60 years (72% of survivors) [1]. While more individuals are surviving cancer, the disease and adverse treatment sequelae are contributing to the increased burden of illness, decreased length and quality of survival, and greater healthcare costs [2]. In women diagnosed with breast cancer, physical function decreases post-diagnosis and remains lower than pre-cancer physical function levels 10 years later [3]. Similarly, those diagnosed at an older age (i.e., ≥60 years old), often experience greater declines in physical functioning with impaired recovery [4, 5].

Increasing physical activity (PA), even light intensity, reduces functional decline in cancer survivors [6]. While numerous intensive diet and exercise interventions have proven beneficial to cancer survivors, these results are often short-term. Without sustained support, long-term adherence is problematic in many behavioral interventions. To have lasting health benefits, permanent lifestyle changes are needed. Gardening interventions have the potential for sustainability since gardening 1) involves a variety of activities which prevent satiation common with other forms of exercise; 2) provides a sense of accomplishment and zest for life that come from nurturing and observing new life and growth [6, 7], and 3) imparts natural prompts since plants require regular care (watering, weeding, pest control) and attention (pruning, harvesting) and serve as continual and dynamic behavioral cues. As the vast majority of cancer survivors are seeking complementary and alternative medical therapies to maintain or improve their health [8], gardening interventions may be widely acceptable and sustainable.

The current Harvest for Health initiative includes two randomized controlled trials, using a home-based vegetable gardening approach to improve PA, dietary intake, and physical functioning of two survivor groups: 1) survivors of breast cancer, and 2) older survivors of cancers with five-year relative survival rates of 60% or greater. Survivors are individually paired with Master Gardeners (MG) who have undergone 100 hours of training through the Alabama Cooperative Extension System (ACES). These MGs interface bimonthly with the survivors to mentor in the planting and maintenance of three home-based vegetable gardens over the course of a year.

Undertaken as feasibility studies, both are currently in progress. The purpose of this paper is to report the design, methodology, and challenges encountered during implementation of these two similar feasibility studies in two unique cancer survivor populations.

Methods

Study Population and Overview

Intervention Development

Harvest for Health was first conducted as a single-arm pilot study with 12 adult and child cancer survivors [7]. Results suggested that the vegetable gardening intervention was associated with promising benefit, not only on improving the diet, but also on physical functioning, and physical activity. The potential impact on physical activity was not associated solely with the activity of gardening, but rather the garden appeared to serve as a “cue to action,” that drew survivors outside and incited more activity through extra yard work and walking [7]. Two studies are currently underway to build capacity with the ACES and test the feasibility of delivering the yearlong vegetable gardening intervention to adult cancer survivors. In 2013, the Birmingham Breast Cancer Survivors study (BBCS), funded by the Women’s Breast Health Fund of the Community Foundation of Greater Birmingham, began enrolling female breast cancer survivors within the five-county region defining the Birmingham metropolitan area (i.e., Jefferson, Shelby, Blount, St. Clair, and Walker counties). All participants are to be assessed over a two-year period using a waitlist control design with the waitlist control group receiving the intervention in the second year. Target accrual for the BBCS was 100 participants. In 2014, the Alabama Senior Cancer Survivors study (ASCS), funded by the National Cancer Institute (R21 CA182508/NCT02150148), began enrolling male and female cancer survivors aged 60 years and older throughout the state of Alabama with a target accrual of 46. In the ASCS, participants are assessed throughout one year, and the control group receives the intervention after final assessment. The primary aim of both studies is to determine intervention feasibility and acceptability; secondary aims are to explore effects on objective and subjective measures of diet, physical activity and function, and QOL and examine participant factors associated with potential effects.

Eligibility Criteria

See Table 1.

Table 1.

Inclusion criteria for the Harvest for Health studies

| BBCS | ASCS | |

|---|---|---|

| Female breast cancer survivor; no limitation on stage, age, or treatment status. | X | |

| Adults ≥60 years of age diagnosed with a loco-regionally staged cancer associated with an 60% or greater 5-year relative survival rate including, but not limited to the following: in situ bladder; localized and regional: breast (female), Hodgkin Lymphoma, prostate, and thyroid; localized: cervix, colon and rectum, corpus and uterus, kidney/renal pelvis, Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma, oral cavity/pharynx, ovary, small intestine, and soft tissues. |

X | |

| Household has ready access to water and does not currently tend a vegetable garden. | X | X |

| Residence can accommodate 4 EarthBoxes or a 4’×8’ raised bed with ample sunshine (i.e., >6 hours/day). |

X | X |

| English speaking/writing at 5th-grade level or higher and able to understand verbal/written instruction. |

X | X |

| At higher risk for functional decline (≥1 physical function (PF) limitation as defined by the SF-36 PF subscale). |

X | X |

| Not currently eating at least 5 servings of fruits and vegetables (F&V)/day nor exercising at least 150 minutes/week. |

X | X |

| Community-dwelling and residence within 15 miles of a MG volunteering in the study. | X | X |

| Willingness to be randomized to either study arm and participate in all assessments. | X | X |

| Not told by a physician to limit PA and no pre-existing medical condition(s) that preclude(s) (A) increased consumption of F&V, e.g., pharmacologic doses of warfarin or (B) gardening, e.g., paralysis, severe orthopedic conditions, impending hip or knee replacement (within 6 months), end- stage renal disease, dementia, blindness, unstable angina, untreated stage 3 hypertension, or recent history of myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, or pulmonary conditions that required oxygen or hospitalization within 6 months. |

X | X |

Screening and Randomization

In the BBCS, the screening and evaluation process took place from August 2013 through May 2014. Consent forms and screeners were mailed to interested, eligible survivors and were reviewed on the telephone. After undergoing the distance-based screening and informed consent process, eligible survivors deciding to participate signed the consent form and returned it to the study office using a pre-addressed, postage-paid mailer. An additional consent form was provided for them to keep. Randomization was performed off-site following the completion of the baseline assessment by the use of a randomization list created by the study statistician and was stratified by county and number of physical function limitations based on permuted blocks. Participants were randomized to either the gardening intervention immediately or to a wait-listed control group (who would receive the intervention after a 1-year delay).

In the ASCS, the screening and evaluation process took place from June 2014 through August 2014. Informed consent, screening, and randomization were conducted in the same manner as the BBCS though stratification variables only included physical functioning (one limitation or more than one limitation).

The Intervention

Both Harvest for Health interventions are guided primarily by the Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) [9] to emphasize the fundamental concepts of self-efficacy and skills development to mediate behavior change (gardening). MGs are trained to promote self-efficacy by serving as role models, encouraging incremental goal setting, providing reinforcement and encouragement as appropriate, strategizing to overcome barriers, creating expectancy that gardening will result in desired outcomes, and skills training for high-risk situations to enhance behavioral capability. Participants also are asked to keep a gardening journal (self-monitoring).

The Harvest for Health intervention also draws upon the Social Ecological Model (SEM) [10], since effects on physical function, F&V intake, and PA are influenced by interactive relationships between the survivor and his/her social/physical environment. Vegetable gardening, in practice, has multiple levels of influence such as individual factors (e.g., demographics), interpersonal factors (e.g., social support), and community factors (e.g., availability of gardening supplies/support).

For both studies, MGs assist and mentor study participants. MG programs are overseen and certified by the Cooperative Extension within land grant universities in all 50 United States. ACES supports 44 county and regional Master Gardener Associations with approximately 1,800 new and veteran volunteers reporting 209,974 volunteer hours statewide in 2013.

MGs are individually matched with survivors based primarily on geographic proximity (<15 miles between residences) and are initially introduced at Meet n’ Greet events at the launch of each regional cohort. These events are essential to the program’s success as they 1) provide UAB staff an opportunity to explain the study purpose and goals; 2) provide ACES staff an opportunity to teach the basics of vegetable gardening to study participants and provide them with tools, seeds, and starter plants for their first garden; 3) provide ACES staff an opportunity to train MGs and outline expectations for MGs and participants with regards to planting and maintaining their gardens over the next year; 4) allow MGs and survivors a chance to meet, interact, and start planning their first garden; and 5) allow UAB and ACES staff to solve potential logistic or planning problems in real time so that the intervention would be initiated promptly.

In both studies, the MG works with their assigned cancer survivor to plan, plant, tend, and harvest three gardens over the course of a year (Fall: September-December; Spring: January-April; and Summer: May-August). Survivors choose either a 4’×8’ raised bed (homeowners) or four EarthBoxes (EarthBox® by Novelty Manufacturing Co., Lancaster, PA) (apartment or townhome dwellers, renters, those with limited sunlight) which provide comparable square footage. Supplies (Table 2) are either distributed at the Meet n’ Greet meetings or delivered to survivors’ homes. Survivors were able to keep all supplies, an estimated value of $500.00 per participant covered by the respective grants. MGs assist survivors in assembling gardens and attaining any additional supplies at local nurseries or Extension offices (e.g., soil mix, seeds, plants). MGs teach survivors how to select healthy plants and upon completion of garden setup, check in bi-weekly, alternating between home visits and contact via telephone or email. All contact between MGs and survivors is tracked by UAB and ACES study staff.

Table 2.

Supplies provided to all BBCS and ASCS study participants unless otherwise noted

|

|

The notebook that each survivor receives includes general information on gardening, addresses cancer-specific concerns (e.g., importance of wearing gardening gloves, proper lifting to reduce the risk of lymphedema, back injury, sun protection), and lists contact information for the MGs and study personnel. In addition to these resources, survivors are encouraged to participate in a private Facebook® group, allowing participants to interact with other survivors and MGs on the project.

Waitlist Control Group

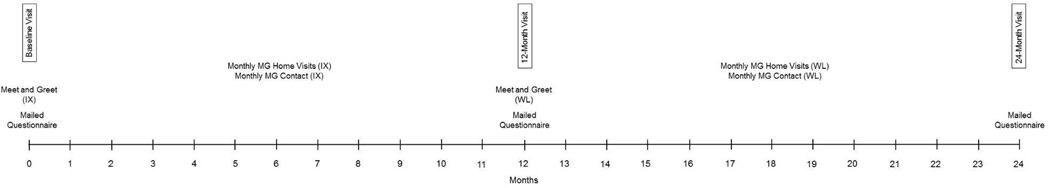

In the BBCS, those randomized to the waitlist control group are followed during year 1 of the study while not receiving the intervention. At the start of year 2, these participants are paired with MGs, given all intervention materials, and monitored for the duration of year 2. Those randomized to the immediate intervention are not intervened upon in year 2 but are assessed again at the end of year 2 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

BBCS timeline

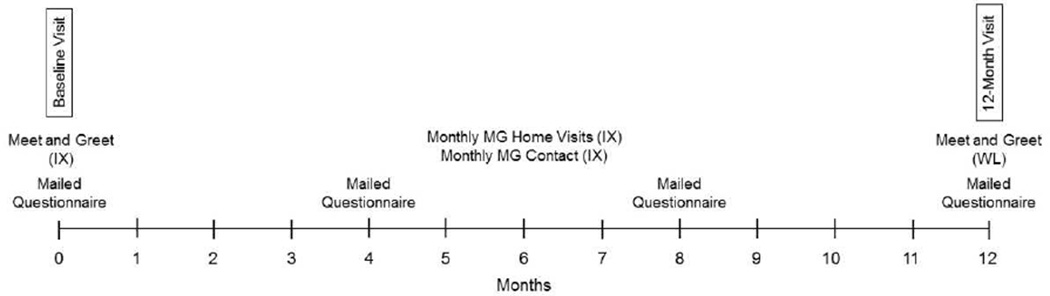

In ASCS, those randomized to the waitlist control group are followed during year 1 of the study while not receiving the intervention (Figure 2). At the end of year 1, these participants are given all intervention materials and participate in local Meet n’ Greets where they are introduced to ACES staff and MGs who help them start their garden, but are not expected to maintain contact. Additionally, they are invited to the private Facebook page and informed they will no longer be followed as study participants.

Figure 2.

ASCS timeline

Measures

Both the BBCS and the ASCS are feasibility studies; thus, the most salient outcomes are feasibility and acceptability. Feasibility is assessed via process data and acceptability through debriefings either at time of drop-out or at completion of the intervention.

Process Data

Accrual benchmarks for both studies were set to achieve at least 80% of the accrual target within 6-months. Likewise, a benchmark of 80% was set to evaluate retention over the course of both studies. These benchmarks were assessed using process data. In addition, participants in both studies are encouraged (in cover letters, as well as in the study notebook) to report any serious health events as soon as practical to the study office, whereupon they are logged to determine their nature and cause, and brought immediately to the attention of the principal investigator. To assess fidelity, photographs of the garden taken at MG monthly visits are collected, as well as data from participants’ gardening journals. Additionally, survivors report MG contact monthly with study staff and MGs report survivor contact monthly with ACES staff. Moreover, at the time of follow-up, the garden is assessed to determine if it is actively being tended.

Debriefing

In both studies, all participants who complete the 12-month gardening intervention are interviewed via telephone. Questions of acceptability are asked of participants (i.e., “How would you rate your experience?” “Based on your experience, would you do it again?”). The debriefing includes questions regarding intentions of future gardening and plans to expand gardening spaces (i.e., “Do you plan to continue to garden and plant on your own?” “Do you plan to expand your garden?”), in addition to soliciting feedback on the most and least helpful components of the intervention (e.g., “How helpful was the notebook…spade…hoe…gardening hose”…etc.), participants also are asked, “Did your garden motivate you to…eat a healthier diet, …eat more vegetables,…try new vegetables, and …be more physically active.” Most items employed a 10-point Likert scale.

In both studies, a variety of secondary outcomes were assessed for the primary purpose of assessing effect size and variation. The experience of collecting these data, as well as their analyses, are considered important for informing power calculations in future studies.

Mailed Questionnaires

In BBCS, participants are mailed questionnaires at all time points prior to home visits. Completed questionnaires are collected at home visits.

In the ASCS, participants are mailed questionnaires at all time points as well. At baseline and 12-month home visits, completed questionnaires are collected. Also, at 4- and 8-months, a subset of items related to health-related quality of life, PA, diet, stress, sleep, and mindfulness are assessed, and participants are provided with a pre-addressed, postage-paid mailer to submit their completed materials (Table 3).

Table 3.

Outcome measures and timing for the BBCS and ASCS studies

| Baseline | 4 mo | 8 mo | 12 mo | 24 mo | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRIMARY OUTCOMES (feasibility and acceptability) | |||||

| FEASIBILITY | |||||

| Process Data: accrual of ≥80% of target within 6 months | BBCS/ASCS | - | - | - | - |

| Process Data: retention of ≥80% of study participants | - | - | - | BBCS/ASCS | BBCS |

| Safety: Absence of Serious Adverse Events Attributable to the Intervention |

Measured continuously after Baseline (BBCS/ASCS) | ||||

| ACCEPTABILITY | |||||

| Debriefing | - | - | - | BBCS/ASCS | BBCS |

| SECONDARY OUTCOMES (to evaluate magnitude and variation of change for future studies) | |||||

| PHYSICAL FUNCTIONING | |||||

| 30-second Chair Stand | BBCS/ASCS | - | - | BBCS/ASCS | BBCS |

| Arm Curl | BBCS/ASCS | - | - | BBCS/ASCS | BBCS |

| Chair Sit and Reach | BBCS/ASCS | - | - | BBCS/ASCS | BBCS |

| Back Scratch | BBCS/ASCS | - | - | BBCS/ASCS | BBCS |

| 8-Foot Get Up and Go | BBCS/ASCS | - | - | BBCS/ASCS | BBCS |

| Timed 8-Foot Walk | ASCS | - | - | ASCS | - |

| Balance Testing | ASCS | - | - | ASCS | - |

| Hand Grip Strength | BBCS/ASCS | - | - | BBCS/ASCS | BBCS |

| 2-Minute Step Test | BBCS/ASCS | - | - | BBCS/ASCS | BBCS |

| BIOLOGICAL SAMPLES | |||||

| Blood Biomarkers | BBCS/ASCS | - | - | BBCS/ASCS | BBCS |

| Stool Sample | BBCS/ASCS | - | - | BBCS/ASCS | BBCS |

| Fingernail & Toenail Sample | BBCS/ASCS | ASCS | ASCS | BBCS/ASCS | BBCS |

| Saliva Sample | BBCS/ASCS | - | - | BBCS/ASCS | BBCS |

| ANTHROPOMETRICS | BBCS/ASCS | - | - | BBCS/ASCS | BBCS |

| DIETARY INTAKE | |||||

| EATS Questionnaire | ASCS | ASCS | ASCS | ASCS | - |

| Diet History Questionnaire | BBCS/ASCS | - | - | BBCS/ASCS | BBCS |

| PHYSICAL ACTIVITY | |||||

| CHAMPS | ASCS | ASCS | ASCS | ASCS | - |

| Godin | BBCS/ASCS | ASCS | ASCS | BBCS/ASCS | BBCS |

| Accelerometry | BBCS/ASCS | - | - | BBCS/ASCS | BBCS |

| HEALTH-RELATED QUALITY OF LIFE | |||||

| SF-36 HRQOL Index | BBCS/ASCS | ASCS | ASCS | BBCS/ASCS | BBCS |

| COMORBIDITIES | |||||

| OARS | BBCS/ASCS | - | - | BBCS/ASCS | BBCS |

| PSYCHOSOCIAL | |||||

| Social Provisions Scale | BBCS/ASCS | - | - | BBCS/ASCS | BBCS |

| Perceived Stress Scale | BBCS/ASCS | ASCS | ASCS | BBCS/ASCS | BBCS |

| FACIT-SP | BBCS/ASCS | ASCS | ASCS | BBCS/ASCS | BBCS |

| Social Readjustment Scale | ASCS | ASCS | ASCS | ASCS | - |

| Super-Utilizer Screener | ASCS | - | - | ASCS | - |

| PSQI | ASCS | ASCS | ASCS | ASCS | - |

| Mindfulness Attention Awareness Scale | ASCS | ASCS | ASCS | ASCS | - |

| MEDIATORS/MODERATORS | |||||

| Community Support | BBCS/ASCS | - | - | BBCS/ASCS | BBCS |

| Self-Efficacy | BBCS/ASCS | - | - | BBCS/ASCS | BBCS |

| Social Support | BBCS/ASCS | - | - | BBCS/ASCS | BBCS |

| DEMOGRAPHICS | |||||

| Participant Information | BBCS/ASCS | - | - | - | - |

Home Visit Assessments

In BBCS, participants are visited in their homes at three time points: Baseline, 12 months, and 24 months (Figure 1). In the ASCS, participants are visited in their homes at two time points: Baseline, and 12 months (Figure 2). At these visits, biospecimens are obtained and physical functioning is assessed. At baseline, available space to situate either a raised bed or 4 Earthboxes evaluated and at follow-up, gardens are examined in those receiving the intervention to assess whether they are being actively tended, a measure of fidelity to the intervention (Table 3).

Physical Functioning

In the BBCS, participants’ physical functioning is assessed using the 30-Second Chair Stand (number of times participant can stand and sit in 30 seconds), Arm Curl (number of times participant can curl and uncurl arm in 30 seconds), Chair Sit and Reach and Back Scratch (measures of flexibility), 8-Foot Get Up and Go, Hand Grip Strength (measured using a dynamometer, (Creative Health Products, Inc., Ann Arbor, MI), and 2-Minute Step Test (measure of endurance) [11–13]. In addition to the above measures, ASCS participants perform the Timed 8-Foot Walk and balance testing [14].

Anthropometrics

Height, weight, and waist circumference are measured in survivors using a portable stadiometer, calibrated scale, and non-stretch tape measure. Measures are taken in light clothing and without shoes to the nearest tenth of a centimeter or kilogram using methods outlined in the Anthropometric Standardization Manual [15].

Biological Measures

In both studies, blood is drawn to examine interleukin-6 (IL-6, biomarker of inflammation) [16], soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule (s-VCAM, marker of endothelial activation related to function and mortality in community-dwelling older adults) [17], D-dimer (predictor of functional decline) [17], and telomerase (biomarker of successful aging) [18–22], all of which have been shown responsive to diet and PA and related functional status and aging [23]. While selected biomarkers are not influenced by fasting [24], some diurnal variation may occur. Thus, time of the draw along with wake time are recorded. Baseline and follow-up visits are scheduled at similar times of day (+2 hours) for each participant to reduce intra-individual variation. Blood is drawn in three vacutainers: one serum separator tube (SST), one sodium citrate-treated tube, and one EDTA-treated vacutainer. Samples are centrifuged immediately after the draw (exception: SST, which is allowed to clot prior to spinning) using portable centrifuges [25, 26]. Serum and plasma are aliquoted from their respective tubes; sera, plasma, and buffy coat/peripheral blood mononuclear cells (peripheral blood mononuclear cells [PBMC]) are stored on dry ice, the latter of which undergoes RNA extraction. Upon return to the laboratory, samples are stored at −80°C until batch analysis at study end.

Plasma IL-6 and s-VCAM are assessed via electrochemiluminescence. Plasma D-dimer is assayed using enzyme-linked immunoassays (ELISA; Dimertest Tripwell EIA kit, American Diagnostica, Greenwich, CT). Telomerase activity is measured in PBMCs using the Telomerase PCR ELISA assay [27]. Assays are performed in duplicate, and reruns are carried out on samples providing discrepant readings (>25%).

To assess the potential impact of the gardening intervention on the microbiome (gut flora have been associated with health outcomes and are impacted by diet, physical activity and environmental change) [28], sterile wipes in sealed plastic bags are mailed to participants before home visits. Participants are instructed to wipe themselves with the sterile wipe after a bowel movement, place the used wipe back into the plastic bag, and then immediately store the sample in their freezer, noting the date and time of collection, until the time of their home visit. Samples are kept on ice and then stored at −80°C until analyzed [29]. Microbe DNA is extracted using a ZR Fecal DNA Miniprep, and the V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene will be PCR-amplified for sequencing on the Illumina Miseq [29, 30]. The Quantitative Insight into Microbial Ecology (QIIME) suite, version 1.7 [31] is used to perform analysis with the addition of a wrapper for QIIME (i.e., QWRAP) [30]. Operational taxonomic units (OTUs) are generated using filtered sequences, which will be clustered at 97% identity and rarified at minimum depth. The Ribosomal Database Project classifier [32] is used to perform the assignment of OTUs, which is informed by the May 2013 version of the Greengenes 16S database [33]. Multiple sequence alignment of OTUs is carried out with PyNAST [34]. Within-sample (alpha) diversity measures are calculated with Shannon and Phylogenetic Diversity [35], and beta diversity calculated using Bray Curtis and weighted and unweighted Unifrac clustering [36]. Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) is performed by QIIME to visualize the dissimilarity matrix (beta-diversity) among the samples.

Saliva is obtained during the home visit. Prior to the visit, the participant is instructed not to consume alcohol, caffeine, or nicotine for 12 hours and not to brush their teeth within 45 minutes. At the time of the visit, the participant rinses their mouth with water 10 minutes prior to collection and is then asked about adherence to abstaining from the above. The saliva sample is frozen at −80°C until analysis.

Nails are clipped by the participant and placed in a plastic sealable bag. Data regarding nail polish and artificial nails are gathered. The nail samples are kept at room temperature until analysis. For cortisol analysis, fingernails and toenails are processed using a slightly modified procedure as described by Warnock et al. [37] and Meyer et al. [38]. Briefly, nail samples are washed twice with 2ml isopropanol and dried overnight. The dried nail samples are added to a pre-weighed tube containing three 5mm steel grinding balls (Retsch, Haan, Germany) and ground using a TissueLyser II (Qiagen Venlo, Netherlands) at 30 Hz for 9 minutes. The speeds and times for the nails’ grinding are optimized (data not shown). Methanol (1 ml) is added per 50mg of powdered nail (w/v) and placed on a rotator for 18 hours at room temperature to extract the cortisol. Samples are then centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 5 minutes. The supernatant (800 µl) is transferred to a clean tube and evaporated under nitrogen gas in a certified fume hood. The evaporated sample is resuspended in 400 µl of phosphate buffered saline (pH 7.4) per 50 mg of ground sample (w/v). Cortisol (hormone indicative of inflammation and stress) [39] is assayed using 25 µl of sample according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Salimetrics, Salivary Cortisol Enzyme Immunoassay Kit, 1–3002, State College, PA). If cortisol readings are outside the range for the standard curve, the samples are either diluted or concentrated and rerun using the same 25 µl volume and within the standard curve. The inter-assay coefficient of variation is 4.7% for the high standard, 14% for the low standard, less than 12% for control biological replicates (n=5), and within the manufacturers recommendations. Preparation and assay of saliva samples are done in accordance with manufacture’s instruction using SalivaBio Oral Swab for collection (Salimetrics, Salivary Cortisol Enzyme Immunoassay Kit, 1–3002, State College, PA). Data are analyzed using StatLIA Enterprise 2.2 software, are represented as nmol/gram for fingernails and toenails and µg/dL for salivary cortisol levels.

Diet and Physical Activity Measurements

In the BBCS, dietary intake is measured via self-report using the NCI Diet History Questionnaire (DHQ-1) [40]. The DHQ is a food frequency questionnaire consisting of 144 food items and supplements and includes portion size questions. In the ASCS, dietary intake is measured via self-report using the Eating at America’s Table (EATS) dietary screener [41] and the DHQ. EATS provides data on F&V intake [41].

PA is measured using the Godin Leisure-Time Exercise Questionnaire (Godin) and accelerometry. The Godin is self-administered and measures usual leisure-time PA during a 7-day period. Frequency is measured in 15-minute increments [42]. Programmed accelerometry units (Actigraph, Inc. Pensacola, FL) objectively measure PA [43, 44]. These accelerometry units are mailed to participants with instructions for 7-day collection and collected by staff during home visits. In the ASCS, PA is measured using the Community Healthy Activities Model Program for Seniors (CHAMPS) Physical Activity Questionnaire for Older Adults [45], the Godin, and accelerometry.

Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQOL)

In both the BBCS and ASCS, the SF-36 HRQOL Index is administered. This instrument provides a global measure of health-related quality of life as well as specific data on eight distinct subscales (vitality, physical functioning, bodily pain, general health perceptions, physical role functioning, emotional role functioning, social role functioning, and mental health) [46, 47].

Comorbidities

In both the BBCS and ASCS, the Older American Resources and Services (OARS) Comorbidity Index is administered to assess the number of chronic medical conditions/symptoms and their functional impact [48]. An additional item assessing falls in the previous year also is included [49].

Psychosocial Measures

In both studies, the Social Provisions Scale (SPS), Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), and Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy – Spiritual Well-being (FACIT-Sp) are administered. In the revised SPS, one of the six subscales assesses the psychosocial benefits of gardening [50, 51]. The PSS is used to measure the degree to which situations in an individual’s life are appraised with stress [52]. The FACIT-Sp is a measure of spiritual well-being in people with cancer [53].

In addition to the above scales, the ASCS also administers the Social Readjustment Scale (SRS), Super-Utilizer Scale (SUS), Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), and Mindfulness Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS). The SRS is a 43-item measure for identifying significant stressful life events [54]. The SUS is a 2-item measure of hospital and emergency room admittance in the past four months. The PSQI assesses sleep quality and disturbances within the previous month [55]. These instruments are administered at baseline, 4- 8- and 12-months.

Mediators

In both the BBCS and ASCS, community support, social support, and self-efficacy are measured as mediators. To measure community support, participants independently assess their local environment for support of vegetable gardening considering factors of availability of garden stores, presence of pests, neighborhood covenants that impose landscaping restrictions, and a sense of belonging with other gardeners in the local community on a 7-point Likert scale with one being ‘environment is extremely unsupportive for gardening’ and seven being ‘environment is extremely supportive for gardening.’ To measure social support and self-efficacy, the Social Support and Eating Habits and Exercise Surveys [56] have been adapted for gardening using identical anchors.

Demographic and Health-Related Characteristics

In both studies, demographic data are gathered (age, race, ethnicity, education level, occupation, marital status, income, and smoking status) at baseline. Also, cancer-related data are obtained at this time, e.g., cancer site and stage, diagnosis year and treatment (i.e., surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, hormone therapy); cancer site, stage, and year of diagnosis was obtained from registries or oncologists whereas cancer treatment is self-reported.

Power and Statistical Considerations

The accrual target for the BBCS was 100 participants and was based solely on building MG capacity in the greater Birmingham metropolitan area (i.e., establishing a critical mass of trained MGs who could sustain the intervention long-term). The sample size of 46 in the ASCS trial is based on power analysis which assumed an improvement of 5 points or more in the SF-36 physical function subscale in 55% of the immediate intervention arm as compared to 15% of the waitlist arm using a Fisher’s exact test at an alpha level of .05. One-sided testing (considered appropriate for feasibility trials) provides 79% power assuming an ultimate sample size of 20 per arm after 13% attrition. Both trials are aimed at established basic metrics of feasibility (i.e., achieving at least 80% of the targeted accrual within a 6-month period and retaining at least 80% of participants over the course of each study). Moreover, a safety benchmark of observing no serious adverse events directly associated with the intervention also is assessed. In addition, process data are to be analyzed to determine differences between refusers and enrollees, and dropouts versus completers using chi-square (for categorical variables such as race and arm assignment) and t-tests (for continuous variables such as age). Frequencies related to study satisfaction are summed and reported. Between group differences in baseline and 1-year change in physical performance tests, biomarkers of physical function and aging, F&V intake, diet quality, PA, and QOL are to be quantified using means and stand deviations and compared using pooled t-tests. Logistic regression will be used to evaluate subject characteristics (e.g., age, education, number of morbidities, sex) associated with adherence to gardening and with improvements in F&V intake, PA, and improvement of physical function of 5 points or more on the SF-36 physical function subscale.

Results

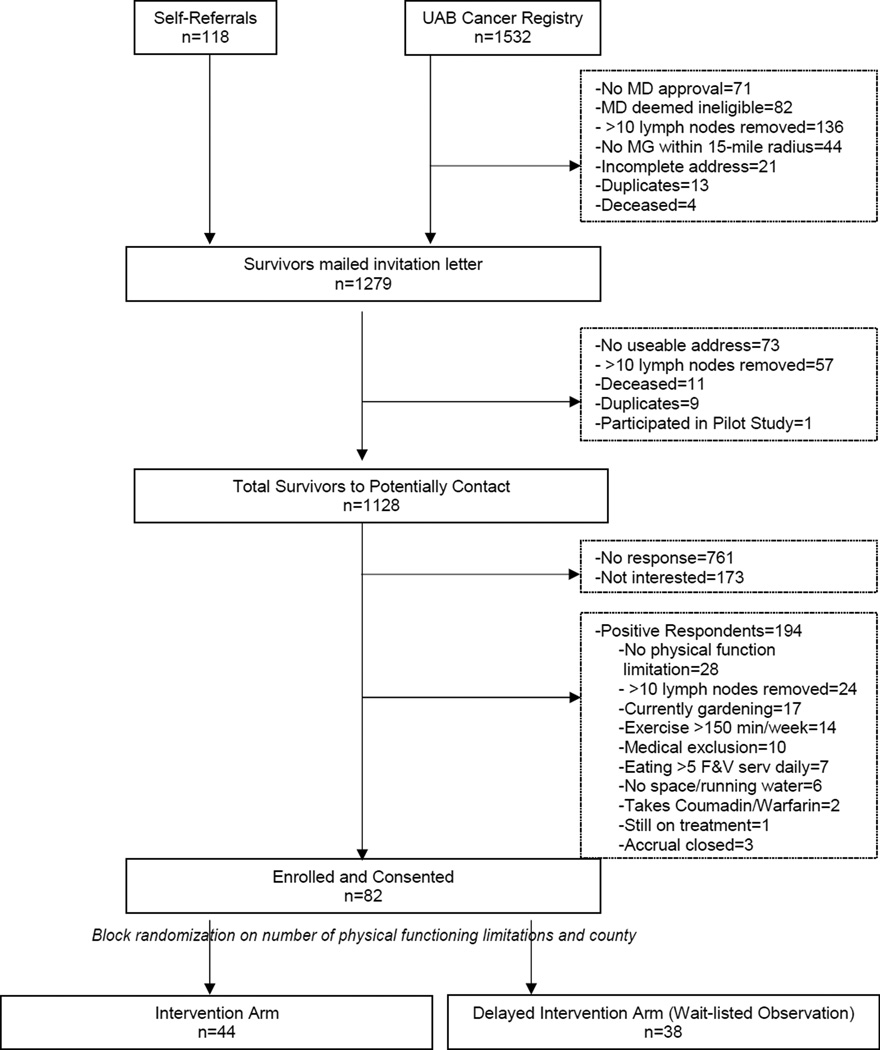

Figure 3 depicts recruitment for BBCS, starting with a potential pool of 1,650 breast cancer survivors. A positive response is determined by a completed screener and signed consent form (n=367, 32.6% response rate). No significant differences were observed in age, cancer stage, or time since diagnosis in those who enrolled versus those who did not. This study did not have complete data in regards to race comparing those enrolled versus those not.

Figure 3.

Recruitment and accrual diagram (BBCS)

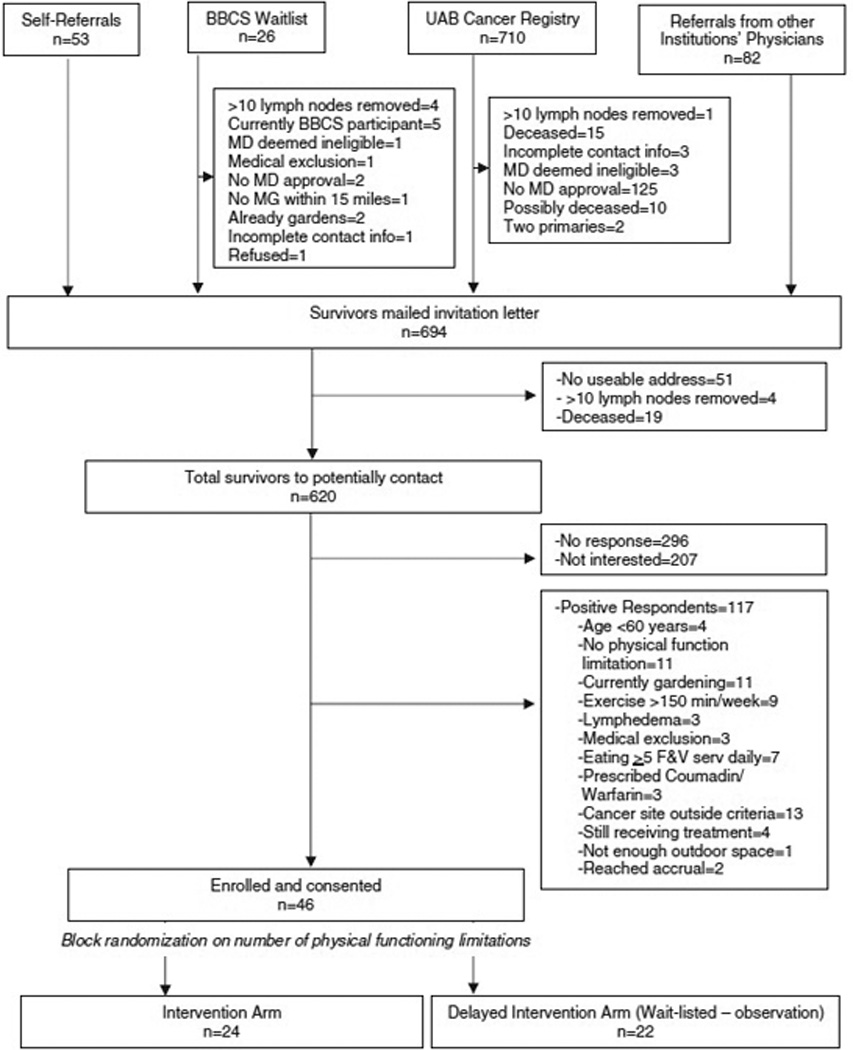

Figure 4 describes the ASCS participant pool (n=871). Again, a positive response is determined by a completed screener and signed consent form (n=324, 52.3% response rate). One participant did not receive the intervention as planned due to an unrelated physical injury immediately after randomization. No significant differences were detected in age, gender, cancer site, or time since diagnosis in those who enrolled versus those who did not; however, we saw a larger proportion of lower stage cancers in the enrolled group as compared to those not enrolled. We also observed a disparity in those identifying as Black (2.2% of those enrolled versus 17.0% of those not enrolled, p=.02), with the main reasons being a lack of response, refusal, and ineligibility.

Figure 4.

Recruitment and accrual diagram (ASCS)

The BBCS had a dead letter rate of 67.4% while the ASCS had a dead letter rate of 47.7%. In both studies, online search engines were used to locate addresses of survivors whose initial letters were returned due to inactive addresses.

In the BBCS, we reached 82% accrual within a 9-month period. Time was a limiting factor in achieving 100% accrual, and initially, our goal was to recruit 20 participants from each of five area counties. The most densely populated and adjacent counties were easily filled in the recruitment windows; however, the more rural counties were predominantly farming communities, with many cancer survivors already vegetable gardening and, therefore, ineligible. When this theme became apparent, we recruited more participants from the more populous counties but had to close recruitment to allow for completion of the intervention that encompassed three full growing seasons.

In the ASCS, a similar challenge arose in recruitment with one of the target counties being a farming community. We were able to collaborate with several statewide cancer centers and hospitals to assist with recruitment, which allowed us to have a larger footprint in the state. This collaboration was beneficial in exposing more MGs and Extension offices to the study and adapting the intervention to the unique growing conditions in the different regions of the state. We had 100% accrual in ASCS within the 6-month recruitment period. Eligibility was also expanded in the ASCS from those ≥65 years old, cancer sites with 5-year relative survival rates of ≥80%, and a maximum of five years since diagnosis to ≥60 years old, cancer sites with 5-year relative survival rates of ≥60%, and no maximum time since diagnosis.

Baseline demographics of each study’s participants can be seen in Table 4. Both Harvest for Health studies were made up of participants that were mostly white with at least some college education, married, overweight or obese, reporting three or more physical functioning limitations, eating less than two servings of F&V daily, and getting less than one hour weekly of PA. The BBCS had exclusively female breast cancer survivors while the ASCS had a majority of female breast cancer survivors. The BBCS accrued a racially representative sample whereas the ASCS was low in the representation of the Black population.

Table 4.

Participant baseline demographics

| Characteristic | Subgroup | BBCS (n=82) |

ASCS (n=46) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 82 (100%) | 32 (69.6%) |

| Male | - | 14 (30.4%) | |

| Race | Black | 22 (26.8%) | 1 (2.2%) |

| White | 60 (73.2%) | 45 (97.8%) | |

| Mean Age (SD) | 60.2 (11.1) | 70.3 (8.0) | |

| Education | <High school degree | 5 (6.1%) | 4 (8.7%) |

| High school degree | 7 (8.5%) | 5 (10.9%) | |

| Some college | 25 (30.5%) | 12 (26.1%) | |

| College graduate | 19 (23.2%) | 9 (19.6%) | |

| Post-college | 24 (29.3%) | 12 (26.1%) | |

| Marital Status | Married or stable union | 48 (58.5%) | 26 (56.5%) |

| Widowed | 6 (7.3%) | 13 (28.3%) | |

| Separated | 5 (6.1%) | - | |

| Single | 5 (6.1%) | 2 (4.3%) | |

| Divorced | 16 (19.5%) | 3 (6.5%) | |

| Other | - | 2 (4.3%) | |

| Mean BMI (SD) | 30.7 (6.9) | 28.3 (4.8) | |

| Physical Functioning Limitations | One | 19 (23.2%) | 5 (10.9%) |

| Two | 15 (18.3%) | 9 (19.6%) | |

| Three or more | 48 (58.5%) | 32 (69.6%) | |

| Mean F&V Consumption (SD) | 1.7 (1.2) | 1.7 (1.1) | |

| Mean Minutes of PA (SD) | Moderate | 33.9 (57.7) | 34.5 (60.4) |

| Vigorous | 3.8 (16.8) | 11.1 (34.3) | |

| Cancer Type | Breast | 82 (100%) | 27 (58.7%) |

| Bladder | - | 1 (2.2%) | |

| Colon | - | 2 (4.3%) | |

| Kidney | - | 2 (4.3%) | |

| Lung | - | 1 (2.2%) | |

| Lymphoma | - | 2 (4.3%) | |

| Multiple Myeloma | - | 1 (2.2%) | |

| Pancreas | - | 3 (6.5%) | |

| Prostate | - | 4 (8.7%) | |

| Thyroid | - | 1 (2.2%) | |

| Tongue | - | 1 (2.2%) | |

| Multiple Sites | - | 1 (2.2%) |

Discussion

To our knowledge, these two investigations plus the initial pilot study of 12 subjects [7], are the first home-based vegetable gardening intervention trials among cancer survivors or any patient population. Both BBCS and ASCS provide cancer survivors with the opportunity to gain skills that promote lifelong changes in their lifestyle behaviors and may ultimately improve their overall health and quality of life.

Challenges Encountered and Overcome

Initial contact with cancer survivors proved to be quite a challenge. Despite using first class postage, which provides forwarding of mail and correction of addresses, many potential participants did not have known addresses or had moved recently. Often, long-term survivors do not maintain contact with their oncologist or are not followed long-term by cancer registries [57–60]. Therefore, new recruitment strategies are needed that are not reliant on oncology offices and networks. Fortunately, we were able to locate many cancer survivors using available search engines, which would be less feasible in a sufficiently powered study [61].

Recruitment in the BBCS changed from a five-county approach to a mostly two-county approach as three of the counties were largely reliant on farming, and many of the survivors already garden. The ASCS also had to change recruitment areas from a two-city approach to a statewide approach for the same reason. Eligibility criteria in ASCS were expanded during recruitment as mentioned previously, allowing for a more diverse group of cancer survivors.

Two participants from each trial withdrew after being randomized to the waitlist. While all participants, immediate intervention and wait-listed, are promised gardening supplies, this proved not enough for all participants. Future studies of this kind will have to find a way to keep those wait-listed engaged while not tampering with potential study results.

The lessons learned in implementing this RCT may be useful in the design of other holistic and sustainable lifestyle intervention studies in cancer survivors. Data from BBCS and ASCS may assist future research dedicated to this purpose and guide design and implementation of such studies.

Strengths

The cancer survivors in both the ASCS and BBCS had insufficient PA and F&V consumption at baseline (Table 4) which increased in participants enrolled in our first pilot study [7]. Additionally, cancer survivors are at a heightened risk for many health conditions that are influenced by health behaviors (e.g., second cancers, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes) [24, 61–76]. Accelerated functional decline is an acknowledged concern among cancer survivors [77, 78]. Findings suggest that a gardening intervention may hold particular promise for this population as it addresses all these aspects.

The BBCS accrued 80% of its goal with a mean age of 60.2 years and the ASCS accrued 100% of its goal with a mean age of 70.3 years. As older adults, particularly those 65 years and older, are underrepresented in research [79], this is a strength of this intervention.

As most people live in more heavily populated areas, the ability to execute this approach in an urban or suburban setting is a strength. The flexibility of this gardening intervention applies to more people than those in rural areas.

Limitations

The majority of those enrolled in both studies were older female breast cancer survivors. While breast is one of the most commonly diagnosed sites, we had hoped for more diversity in cancer diagnoses in the ASCS. In addition, the ASCS lacked racial diversity. Per the grant, we had forecasted that our sample would represent the state of Alabama which is currently 26.7% African American [80]. However, among these older survivors, we accrued just one African-American participant (2.2% of our sample). This lack of minority representation was due mostly to lack of response and refusal to participate from potential participants in this population. While data are scant, of those who refused, comments emerged to the effect, “My ancestors were slaves, and I was raised on a farm - working in the dirt and sweating. Why would I want to go back to that?” Furthermore, it is important to note, Birmingham, AL (where both of these studies originated) has a long history of civil rights unrest and is a mere two hours from Tuskegee, AL, (home of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, leading in part to the Belmont Report and Office for Human Research Protections) [81]. This history has created a mistrust of medical research in the African-American community [82]. It is speculated that there may be somewhat of a cohort effect manifest among older minority survivors who are more sentinel to these events. This cohort effect may be diminishing over time, since there was no problem in accruing a racially representative sample in the BBCS cohort who were on average 10 years younger.

At the time of recruitment, the Alabama State Cancer Registry was at capacity and unable to take on any new studies. This problem has since been solved. This will allow more uniform population-based accrual across the state and a more cost- and resource-efficient means of identifying potential study participants. It also will allow us a more accurate means of assessing the uptake of the intervention and whether potential bias exists. Recruitment of a more diverse sample, in both cancer site and race, will be important to assess the implications of the intervention across different populations.

Research suggests individuals who garden, and especially those who grow their own fruits and vegetables, are more physically active [83, 84], and tend to have healthier diets [85, 86], body weight status [87] and better mental health and acuity [88–96]. The Harvest for Health gardening intervention espouses all these potential benefits, not only in cancer survivors but in other populations as well. The novelty of the Harvest for Health RCTs and the wealth of objective and subjective measures related to quality of life and physical function will be beneficial to future lifestyle intervention study design. Benefits of these studies hold even more promise with the analyses of biological specimens not previously reported longitudinally in relation to an intervention. The greatest promise in Harvest for Health is that it holds the potential to be self-sustaining, a benefit that participants completing the program have repeatedly valued as “priceless.”

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the contributions of study staff (Yuko Tsuruta, M.D., Ph.D., Carrie Howell, Ph.D. and Teresa Martin) and students (Hannah B. Guthrie, Silvana Janssen, Amber Hardeman, Justine Goetzman, Isabella Mak, and Lora Roberson) for their contributions in collecting these data and in recruitment. We also acknowledge Drs. Michael Meshad and Stephen Davidson, as well as Amber Davis of East Alabama Medical Center, Cheryl Matrella of the UAB Cancer Care Network, and Bob Shepard for their contributions related to recruitment. Further, the authors appreciate the efforts of Susan Rossman, Leonora Roberson, Mary Beth Shaddix Berner, and Jennifer Hicks for their pioneering spirits and Herculean efforts. We are beholden to Alabama Cooperative Extension agents: Ellen Huckabay, James Miles, Mike McQueen, Lucy Edwards, Mallory Kelley, Danielle Carroll, Nelson Wynn, Bethany O’Rear, Charles Pinkston, Tim Crow, Danny Cain, Dan Porch, Renee Thompson, Ken Creel, and Eric Schavey. We also are grateful for the contributions of Madeline Harris, RN, MSN, OCN, and investigators at the Mitchell Cancer Institute (Margaret Murray Sullivan and Paul Howell). We are thankful for the generous in kind contributions of 5 Points Hardware, Maple Valley Nursery, Birmingham Botanical Gardens, Bonnie Plants, the W. Atlee Burpee & Company, Atlas Seeds, Territorial Seeds, Johnny’s Seeds, and the Little Garden Club. We also acknowledge funding provided by the Women’s Breast Health Fund of the Community Foundation of Greater Birmingham, the Diana Dyer Endowment of the American Institute of Cancer Research, National Cancer Institute (R21 CA182508, R25 CA047888 and 5R25 CA76023), and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases P30 DK079626. Most of all, we thank all of the survivors and MGs who make these studies possible, including Nancy Smith and LeAnne Porter who are with us in spirit.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. Cancer Treatment and Survivorship Facts & Figures 2014–2015. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Cancer Institute. SEER Cancer Statistics Factsheets: Female Breast Cancer. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones SM, LaCroix AZ, Li W, Zaslavsky O, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Weitlauf J, Danhauer SC. Depression and quality of life before and after breast cancer diagnosis in older women from the Women’s Health Initiative. J Cancer Surviv. 2015;9(4):620–629. doi: 10.1007/s11764-015-0438-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hewitt M, Rowland JH, Yancik R. Cancer Survivors in the United States: Age, Health, and Disability. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2003;58(1):M82–M91. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.1.m82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sweeney C, Schmitz KH, Lazovich D, Virnig BA, Wallace RB, Folsom AR. Functional limitations in elderly female cancer survivors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98(8):521–529. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blair CK, Morey MC, Desmond RA, Cohen HJ, Sloane R, Snyder DC, Demark-Wahnefried W. Light-intensity activity attenuates functional decline in older cancer survivors. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2014;46(7):1375–1383. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blair CK, Madan-Swain A, Locher JL, Desmond RA, de Los Santos J, Affuso O, Demark-Wahnefried W. Harvest for health gardening intervention feasibility study in cancer survivors. Acta Oncol. 2013;52(6):1110–1118. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2013.770165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ojukwu M, Mbizo J, Leyva B, Olaku O, Zia F. Complementary and Alternative Medicine Use Among Overweight and Obese Cancer Survivors in the United States. Integr Cancer Ther. 2015;14(6):503–514. doi: 10.1177/1534735415589347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bandura A. Health promotion from the perspective of social cognitive theory. Psychology & Health. 1998;13(4):623–649. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stokols D. Social ecology and behavioral medicine: implications for training, practice, and policy. Behav Med. 2000;26(3):129–138. doi: 10.1080/08964280009595760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, Glynn RJ, Berkman LF, Blazer DG, Wallace RB. A Short Physical Performance Battery Assessing Lower Extremity Function: Association With Self-Reported Disability and Prediction of Mortality and Nursing Home Admission. Journal of Gerontology. 1994;49(2):M85–M94. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.2.m85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rikli RE, Chodzko-Zajko W, Rikli RE, Jones CJ. The Development and National Norming of a Functional Fitness Test for Older Adults. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 1999;31(Supplement):S399. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rikli RE, Jones CJ. Functional fitness normative scores for community-residing older adults, ages 60–94. Journal of Aging and Physical Activity. 1999;7(2):162–181. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, Glynn RJ, Berkman LF, Blazer DG, Wallace RB. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J Gerontol. 1994;49(2):M85–M94. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.2.m85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lohman TJ, Roache AF, Martorell R. Anthropometric Standardization Reference Manual. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 1992;24(8):952. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferrucci L, Harris TB, Guralnik JM, Tracy RP, Corti M-C, Cohen HJ, Havlik RJ. Serum IL-6 Level and the Development of Disability in Older Persons. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1999;47(6):639–646. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb01583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huffman KM, Pieper CF, Kraus VB, Kraus WE, Fillenbaum GG, Cohen HJ. Relations of a marker of endothelial activation (s-VCAM) to function and mortality in community-dwelling older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011;66(12):1369–1375. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Epel ES, Lin J, Wilhelm FH, Wolkowitz OM, Cawthon R, Adler NE, Blackburn EH. Cell aging in relation to stress arousal and cardiovascular disease risk factors. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2006;31(3):277–287. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ludlow AT, Zimmerman JB, Witkowski S, Hearn JW, Hatfield BD, Roth SM. Relationship between physical activity level, telomere length, and telomerase activity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40(10):1764–1771. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31817c92aa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ren H, Zhao T, Wang X, Gao C, Wang J, Yu M, Hao J. Leptin upregulates telomerase activity and transcription of human telomerase reverse transcriptase in MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;394(1):59–63. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.02.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sundin T, Hentosh P. InTERTesting association between telomerase, mTOR and phytochemicals. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2012;14:e8. doi: 10.1017/erm.2012.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Werner C, Furster T, Widmann T, Poss J, Roggia C, Hanhoun M, Laufs U. Physical exercise prevents cellular senescence in circulating leukocytes and in the vessel wall. Circulation. 2009;120(24):2438–2447. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.861005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoebeeck LI, Rietzschel ER, Langlois M, De Buyzere M, De Bacquer D, De Backer G, Huybrechts I. The relationship between diet and subclinical atherosclerosis: results from the Asklepios Study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2011;65(5):606–613. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2010.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rentoukas E, Tsarouhas K, Kaplanis I, Korou E, Nikolaou M, Marathonitis G, Tsitsimpikou C. Connection between telomerase activity in PBMC and markers of inflammation and endothelial dysfunction in patients with metabolic syndrome. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e35739. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoyo C, Grubber J, Demark-Wahnefried W, Lobaugh B, Jeffreys AS, Grambow SC, Schildkraut JM. Predictors of Variation in Serum IGFI and IGFBP3 Levels in Healthy African American and White Men. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2009;101(7):711–716. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30981-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoyo C, Grubber J, Demark-Wahnefried W, Marks JR, Freedland SJ, Jeffreys AS, Schildkraut JM. Grade-specific prostate cancer associations of IGF1 (CA)19 repeats and IGFBP3-202A/C in blacks and whites. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99(7):718–722. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saldanha SN, Andrews LG, Tollefsbol TO. Analysis of telomerase activity and detection of its catalytic subunit, hTERT. Analytical Biochemistry. 2003;315(1):1–21. doi: 10.1016/s0003-2697(02)00663-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.David LA, Maurice CF, Carmody RN, Gootenberg DB, Button JE, Wolfe BE, Turnbaugh PJ. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature. 2014;505(7484):559–563. doi: 10.1038/nature12820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Demark-Wahnefried W, Nix JW, Hunter GR, Rais-Bahrami S, Desmond RA, Chacko B, Grizzle WE. Feasibility outcomes of a presurgical randomized controlled trial exploring the impact of caloric restriction and increased physical activity versus a wait-list control on tumor characteristics and circulating biomarkers in men electing prostatectomy for prostate cancer. BMC Cancer. 2016;16(1):61. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2075-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kumar R, Eipers P, Little RB, Crowley M, Crossman DK, Lefkowitz EJ, Morrow CD. Getting started with microbiome analysis: sample acquisition to bioinformatics. Curr Protoc Hum Genet. 2014;82:1881–1829. doi: 10.1002/0471142905.hg1808s82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Caporaso JG, Lauber CL, Walters WA, Berg-Lyons D, Lozupone CA, Turnbaugh PJ, Knight R. Global patterns of 16S rRNA diversity at a depth of millions of sequences per sample. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 108 Suppl. 2011;1:4516–4522. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000080107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang Q, Garrity GM, Tiedje JM, Cole JR. Naive Bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73(16):5261–5267. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00062-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.DeSantis TZ, Hugenholtz P, Larsen N, Rojas M, Brodie EL, Keller K, Andersen GL. Greengenes, a chimera-checked 16S rRNA gene database and workbench compatible with ARB. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72(7):5069–5072. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03006-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Caporaso JG, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, DeSantis TZ, Andersen GL, Knight R. PyNAST: a flexible tool for aligning sequences to a template alignment. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(2):266–267. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Faith DP, Baker AM. Phylogenetic diversity (PD) and biodiversity conservation: some bioinformatics challenges. Evolutionary Bioinformatics Online. 2006;2:121–128. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lozupone C, Knight R. UniFrac: a new phylogenetic method for comparing microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71(12):8228–8235. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.12.8228-8235.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Warnock F, McElwee K, Seo RJ, McIsaac S, Seim D, Ramirez-Aponte T, Young AH. Measuring cortisol and DHEA in fingernails: a pilot study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2010;6:1–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meyer J, Novak M, Hamel A, Rosenberg K. Extraction and analysis of cortisol from human and monkey hair. J Vis Exp. 2014;(83):e50882. doi: 10.3791/50882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.DeSantis AS, DiezRoux AV, Hajat A, Aiello AE, Golden SH, Jenny NS, Shea S. Associations of salivary cortisol levels with inflammatory markers: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012;37(7):1009–1018. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.National Institutes of Health, Applied Research Program, & National Cancer Institute. Diet History Questionnaire, Version 1.0. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Subar AF, Thompson FE, Kipnis V, Midthune D, Hurwitz P, McNutt S, Rosenfeld S. Comparative Validation of the Block, Willett, and National Cancer Institute Food Frequency Questionnaires : The Eating at America’s Table Study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2001;154(12):1089–1099. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.12.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Amireault S, Godin G, Lacombe J, Sabiston CM. The use of the Godin-Shephard Leisure-Time Physical Activity Questionnaire in oncology research: a systematic review. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2015;15:60. doi: 10.1186/s12874-015-0045-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Welk GJ, Almeida MJ, Church T, Morss G. Laboratory Calibration and Validation of the Biotrainer and Actitrac Activity Monitors. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2002;34(5):S140. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000069525.56078.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Welk GJ, Schaben JA, Morrow JR., Jr Reliability of accelerometry-based activity monitors: a generalizability study. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36(9):1637–1645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stewart AL, Mills KM, King AC, Haskell WL, Gillis D, Ritter PL. CHAMPS Physical Activity Questionnaire for Older Adults: outcomes for interventions. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2001:1126–1141. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200107000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baker F, Haffer SC, Denniston M. Health-related quality of life of cancer and noncancer patients in Medicare managed care. Cancer. 2003;97(3):674–681. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Walters SJ. Using the SF-36 with older adults: a cross-sectional community-based survey. Age and Ageing. 2001;30(4):337–343. doi: 10.1093/ageing/30.4.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fillenbaum C. Multidimensional Functional Assessment of Older Adults: The Duke Older Americans Resources and Services Procedures. PsycCRITIQUES. 1990;35(6) [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen T, Janke M. Gardening as a potential activity to reduce falls in older adults. J Aging Phys Act. 2012;20(1):15–31. doi: 10.1123/japa.20.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sommerfeld A, Waliczek T, Zajicek J. Growing Minds: Evaluating the Effect of Gardening on Quality of Life and Physical Activity Level of Older Adults. Horttechnology. 2010;20(4):705–710. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brown VM, Allen AC, Dwozan M, Mercer I, Warren K. Indoor Gardening and Older Adults: Effects on Socialization, Activities of Daily Living, and Loneliness. Journal of Gerontological Nursing. 2004;30(10):34–42. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-20041001-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A Global Measure of Perceived Stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1983;24(4):385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bredle JM, Salsman JM, Debb SM, Arnold BJ, Cella D. Spiritual Well-Being as a Component of Health-Related Quality of Life: The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy—Spiritual Well-Being Scale (FACIT-Sp) Religions. 2011;2(4):77–94. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Holmes TH, Rahe RH. The social readjustment rating scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1967;11(2):213–218. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(67)90010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Research. 1989;28(2):193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sallis JF, Pinski RB, Grossman RM, Patterson TL, Nader PR. The development of self-efficacy scales for healthrelated diet and exercise behaviors. Health Education Research. 1988;3(3):283–292. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Elston Lafata J, Solloum RG, Fishman PA, Pearson Ritzwoller D, O’Keeffe-Rosetti MC, Hornbrook MC. Preventive care receipt and office visit use among breast and colorectal cancer survivors relative to age- and gender-matched cancer free-controls. J Cancer Surviv. 2015;9(2):201–207. doi: 10.1007/s11764-014-0401-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kukar M, Watroba N, Miller A, Kumar S, Edge SB. Fostering coordinated survivorship care in breast cancer: who is lost to follow-up? J Cancer Surviv. 2014;8:199–204. doi: 10.1007/s11764-013-0323-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Koontz BF, Benda R, De Los Santos J, Hoffman KE, Huq MS, Morrell R, Chen RC. US radiation oncology practice patterns for posttreatment survivor care. Pract Radiat Oncol. 2016;6(1):50–56. doi: 10.1016/j.prro.2015.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Oeffinger KC, McCabe MS. Models for delivering survivorship care. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24(32):5117–5124. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.0474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Aziz NM. Cancer survivorship research: state of knowledge, challenges and opportunities. Acta Oncol. 2007;46(4):417–432. doi: 10.1080/02841860701367878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Simonsick EM, Salive ME, Wallace RB. Lower-extremity function in persons over the age of 70 years as a predictor of subsequent disability. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(9):556–561. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199503023320902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Penninx BWJH, Ferrucci L, Leveille SG, Rantanen T, Pahor M, Guralnik JM. Lower Extremity Performance in Nondisabled Older Persons as a Predictor of Subsequent Hospitalization. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2000;55(11):M691–M697. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.11.m691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Aziz N, Rowland J. Trends and advances in cancer survivorship research: challenge and opportunity. Seminars in Radiation Oncology. 2003;13(3):248–266. doi: 10.1016/S1053-4296(03)00024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chapman JA, Meng D, Shepherd L, Parulekar W, Ingle JN, Muss HB, Goss PE. Competing causes of death from a randomized trial of extended adjuvant endocrine therapy for breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(4):252–260. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chen Z, Maricic M, Bassford TL, Pettinger M, Ritenbaugh C, Lopez AM, Leboff MS. Fracture risk among breast cancer survivors: results from the Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(5):552–558. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.5.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chen Z, Maricic M, Pettinger M, Ritenbaugh C, Lopez AM, Barad DH, Bassford TL. Osteoporosis and rate of bone loss among postmenopausal survivors of breast cancer. Cancer. 2005;104(7):1520–1530. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fouad MN, Mayo CP, Funkhouser EM, Irene Hall H, Urban DA, Kiefe CI. Comorbidity independently predicted death in older prostate cancer patients, more of whom died with than from their disease. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57(7):721–729. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2003.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ganz PA. Late effects of cancer and its treatment. Seminars in Oncology Nursing. 2001;17(4):241–248. doi: 10.1053/sonu.2001.27914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Herman DR, Ganz PA, Petersen L, Greendale GA. Obesity and cardiovascular risk factors in younger breast cancer survivors: The Cancer and Menopause Study (CAMS) Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2005;93(1):13–23. doi: 10.1007/s10549-005-2418-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hershman DL, Shao T. Anthracycline cardiotoxicity after breast cancer treatment. Oncology (Williston Park) 2009;23(3):227–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Institute of Medicine, & National Research Council. From cancer patient to cancer survivor: Lost in Transition. Washington, D.C: National Academies Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jemal A, Clegg LX, Ward E, Ries LA, Wu X, Jamison PM, Edwards BK. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2001, with a special feature regarding survival. Cancer. 2004;101(1):3–27. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ketchandji M, Kuo YF, Shahinian VB, Goodwin JS. Cause of death in older men after the diagnosis of prostate cancer. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(1):24–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02091.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kumar S, Shah JP, Bryant CS, Awonuga AO, Imudia AN, Ruterbusch JJ, Malone JM., Jr Second neoplasms in survivors of endometrial cancer: impact of radiation therapy. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;113(2):233–239. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Meadows AT, Varricchio C, Crosson K, Harlan L, McCormick P, Nealon E, Ungerleider R. Research issues in cancer survivorship: report of a workshop sponsored by the Office of Cancer Survivorship, National Cancer Institute. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers, & Prevention. 1998;7:1145–1151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Oeffinger KC, Nathan PC, Kremer LC. Challenges after curative treatment for childhood cancer and long-term follow up of survivors. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2008;55(1):251–273. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2007.10.009. xiii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Centers for Disease Control Prevention (CDC) Cancer survivorship--United States, 1971–2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53(24):526–529. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hutchins LF, Unger JM, Crowley JJ, Coltman CA, Jr, Albain KS. Underrepresentation of patients 65 years of age or older in cancer-treatment trials. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(27):2061–2067. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199912303412706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.United States Census Bureau. QuickFacts Alabama. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 81.The Belmont Report. http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/belmont-report/index.html.

- 82.George S, Duran N, Norris K. A systematic review of barriers and facilitators to minority research participation among African Americans, Latinos, Asian Americans, and Pacific Islanders. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(2):e16–e31. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yabroff KR, Lawrence WF, Clauser S, Davis WW, Brown ML. Burden of illness in cancer survivors: findings from a population-based national sample. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96(17):1322–1330. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djh255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yancik R, Ries LAG. Aging and Cancer in America. Hematology/Oncology Clinics of North America. 2000;14(1):17–23. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8588(05)70275-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Goggins WB, Tsao H. A population-based analysis of risk factors for a second primary cutaneous melanoma among melanoma survivors. Cancer. 2003;97(3):639–643. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rantanen T. Midlife Hand Grip Strength as a Predictor of Old Age Disability. Jama. 1999;281(6):558. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.6.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Taekema DG, Gussekloo J, Maier AB, Westendorp RG, de Craen AJ. Handgrip strength as a predictor of functional, psychological and social health. A prospective population-based study among the oldest old. Age Ageing. 2010;39(3):331–337. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afq022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mertens AC, Walls RS, Taylor L, Mitby PA, Whitton J, Inskip PD, Robison LL. Characteristics of childhood cancer survivors predicted their successful tracing. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57(9):933–944. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Picavet HS, Wendel-vos GC, Vreeken HL, Schuit AJ, Verschuren WM. How stable are physical activity habits among adults? The Doetinchem Cohort Study. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(1):74–79. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181e57a6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Park S, Shoemaker C, Haub M. Can older gardeners meet the physical activity recommendation through gardening? Horttechnology. 2008;18(4):639–643. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sommerfeld A, McFarland A, Waliczek T, Zajicek J. Growing minds: Evaluating the relationship between gardening and fruit and vegetable consumption in older adults. Horttechnology. 2010;20(4):711–717. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Devine CM, Wolfe WS, Frongillo EA, Bisogni CA. Life-Course Events and Experiences. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 1999;99(3):309–314. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(99)00080-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lombard K, Forster-Cox S, Smeal D, O’Neill M. Diabetes on the Navajo nation: What role can gardening and agriculture extension play to reduce it? Rural Remote Health. 2006;6(4):640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Clarke E. Gardening as a therapeutic experience. Am J Occup Ther. 1950;4(3):109–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lee Y, Kim S. Effects of indoor gardening on sleep, agitation, and cognition in dementia patients--a pilot study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23(5):485–489. doi: 10.1002/gps.1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Tse MM. Therapeutic effects of an indoor gardening programme for older people living in nursing homes. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19(7–8):949–958. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.02803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]