Abstract

Objectives

Patients with end-stage renal disease can receive dialysis at home or in-center. In 2004 the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services reformed physician payment for in-center hemodialysis care from a capitated to a tiered fee-for-service model, augmenting physician payment for frequent in-center visits. We evaluated whether payment reform influenced dialysis modality assignment.

Study Design

Cohort study of patients starting dialysis in the US in the three years before and after payment reform.

Methods

We conducted difference-in-difference analyses comparing patients with Traditional Medicare coverage (who were affected by the policy) to others with Medicare Advantage (who were unaffected by the policy). We also examined whether the policy had a more pronounced influence on dialysis modality assignment in areas with lower costs of traveling to dialysis facilities.

Results

Patients with Traditional Medicare coverage experienced a 0.7% (95% CI 0.2%–1.1%; p=0.003) reduction in the absolute probability of home dialysis use following payment reform compared to patients with Medicare Advantage. Patients living in areas with larger dialysis facilities (where payment reform made in-center hemodialysis comparatively more lucrative for physicians) experienced a 0.9% (95% CI 0.5%–1.4%; p<0.001) reduction in home dialysis use following payment reform compared to patients living in areas with smaller facilities (where payment reform made in-center hemodialysis comparatively less lucrative for physicians).

Conclusions

Transition from a capitated to tiered fee-for-service payment model for dialysis care resulted in fewer patients receiving home dialysis. This area of policy failure highlights the importance of considering unintended consequences of future physician payment reform efforts.

INTRODUCTION

Pay-for-performance (P4P) initiatives tying payment to performance and value of care have become a major component of recent healthcare reform efforts. Since the passage of the Affordable Care Act, and more recently, the repeal of Medicare’s Sustainable Growth Rate, P4P programs are increasingly targeting physician practices directly.1,2 Lessons from prior P4P initiatives can help inform the development of future policies applied to both managed care and fee-for-service settings.

More than 100,000 persons develop end-stage renal disease (ESRD) every year in the US.3 Due to a shortage of organs available for transplantation, the vast majority receive dialysis. In-center hemodialysis is the most common modality; home-based peritoneal or hemodialysis are alternatives that offer more flexibility and lifestyle benefits for some patients.4–8 Ideally, dialysis modality is chosen after careful consideration of medical suitability, and shared decision making among patients, loved ones and care providers.9 Evidence suggests that these discussions occur infrequently10, leading many to conclude that home dialysis therapies are underutilized in the US.11,12

It is uncertain whether physicians’ economic incentives influence dialysis modality choice. International comparisons indicate that the relative physician payment for patients on home versus in-center dialysis directly influences the fraction of patients on home dialysis.13 In the US, higher Medicare payment to dialysis facilities for home therapies associated with the 2011 ESRD Prospective Payment System (“bundling”) coincided with a substantial increase in the use of peritoneal dialysis.3,14 Yet, surveys of nephrologists suggest that patient preferences and health are the primary factors considered when recommending a dialysis modality, rather than economic factors.11,15

In 2004, in an effort to align economic incentives and encourage high quality care, the Centers for Medicare and Medicare Services (CMS) transformed payment to physicians caring for patients receiving dialysis from a capitated to a tiered fee-for-service model (Appendix Table A1).16 Under the new payment system, which continues to govern physician dialysis reimbursement, physicians could increase professional fee revenues by seeing patients receiving in-center hemodialysis four or more times per month. While this policy was not focused on the delivery of home dialysis care, it may have influenced dialysis modality decisions by making in-center hemodialysis comparatively more lucrative for some physicians – physician payment for home dialysis therapy remained capitated and decreased slightly.17 In this study, we determine whether the transition to a tiered fee-for-service payment model influenced dialysis modality choices. We hypothesize that patients were less likely to receive home dialysis following payment reform, and that this decrease was more pronounced in places where physicians could increase in-center hemodialysis revenues at lower cost.

METHODS

Data and patient selection

We selected patients who started dialysis in the US from January 1, 2001 through December 31st, 2006 – the three years prior to and following physician payment reform. We excluded patients who received a kidney transplant within 60 days of ESRD onset. We obtained data on patients’ insurance coverage, home ZIP codes, initial dialysis modality, and information about dialysis facilities from the United States Renal Data System (USRDS), a national registry of patients with treated ESRD. We obtained data on patient co-morbidities prior to ESRD from the CMS Medical Evidence Report (CMS-2728). Due to large number of missing values for Quételet’s (body mass) index (BMI), hemoglobin, and albumin, we used multiple imputation to estimate missing values.18–20 Information on population density came from census-based rural-urban commuting area codes.21 Information on hospital referral region (HRR) came from the Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care.22

Outcomes and Study Design

The primary study outcome was the initial dialysis modality chosen, as reported by the nephrologist to CMS. We categorized dialysis modality as in-center hemodialysis or home dialysis, where home dialysis included home hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis.

We used several difference-in-difference models to examine the effect of payment reform on dialysis modality. Difference-in-difference analysis is an econometric method commonly used to analyze policy.23 Difference-in-difference analyses separate patients into “treatment” and “control” groups. The “treatment” group includes patients who were affected by the policy of interest, while the “control” group includes patients who were not subject to the policy. Thus, any changes observed in the control group reflect changes in the population from measures not changed by the policy. The difference in the change of the outcome after implementation of the policy between the treatment and control groups characterizes the policy’s effect.

Comparison groups

We formed comparison groups from two separate cohorts. In an “insurance coverage” cohort, we selected patients enrolled in either Traditional Medicare as a primary payer or Medicare Advantage prior to start of dialysis. In this analysis, we included patients 65 or older at ESRD onset because patients are not permitted to enroll in Medicare Advantage if ESRD (rather than age) is their qualifying criterion; thus, virtually all patients with ESRD with Medicare Advantage are 65 or older. We conducted a difference-in-difference analysis comparing the choice of dialysis modality among patients with Traditional Medicare versus Medicare Advantage. We chose these groups because payment for services provided to patients with Traditional Medicare was affected by payment reform, while payment for services provided to patients with Medicare Advantage was not.

In a “Non-HMO Medicare” cohort, we selected patients with Traditional Medicare as a primary payer, or waiting for Medicare coverage, at the onset of dialysis. Because the majority of patients in the US who develop ESRD qualify for Medicare within 90 days of ESRD onset, we assumed that patients documented as “waiting” for Medicare would soon receive it and that physicians would consider the financial implications of treating these patients as similar to treating patients already covered. In this cohort, we excluded patients with private insurance since they do not qualify for Medicare until after 30 months of ESRD.

We previously demonstrated that the frequency of physician (or advanced practice provider) visits to patients receiving in-center hemodialysis was predominantly related to geographic and dialysis facility factors, rather than patient clinical characteristics.24 Geographic measures – such as dialysis facility size and population density – that determine the costs physicians incur (in resources and time) traveling to visit patients at dialysis facilities have a substantial influence on visit frequency. All else equal, it is more lucrative for physicians to see patients in larger dialysis facilities because physicians can collect revenue for more patient visits after incurring a fixed cost of traveling to a facility. Likewise, it is more lucrative for physicians to see patients in more densely populated areas due to lower travel costs to facilities.

Using the Non-HMO Medicare cohort, we conducted two difference-in-difference analyses to determine whether changes in the choice of dialysis modality following payment reform varied geographically depending upon how costly it was for physicians to see patients more frequently. While the small decrease in physician payment for home dialysis was similar across all geographic regions, the change in physician payment for in-center hemodialysis after 2004 varied geographically. Physicians practicing in areas where the cost of more frequent visits was lower had an opportunity to increase their professional fee revenues after payment reform by assigning more patients to in-center hemodialysis. In contrast, physicians practicing in areas where it was too costly to visit patients four times per month would have experienced little or no increase in professional fee revenues by assigning patients to in-center hemodialysis. We used the two geographic characteristics previously found to be associated with visit frequency, and therefore the relative gain in professional fee revenue from in-center hemodialysis – dialysis facility size and population density – to determine if changes in physician payment influenced dialysis modality choice.

We averaged dialysis facility size across the HRR where patients lived. We calculated dialysis facility size from the average number of patients receiving in-center hemodialysis documented in annual facility surveys in the three years prior to payment reform. We divided HRRs into quintiles based on their average facility size and assessed the proportion of prevalent in-center patients seen four or more times per month (and associated changes in revenues) in the three years following payment reform within each quintile. We observed that the proportion of patients with four or more visits per month was smallest in the lowest mean facility size quintile. Consequently, we categorized HRRs in the lowest quintile of mean facility size as areas with “smaller facilities.”

We dichotomized population density into “small town/rural” and “non-small town/rural.” The differences in visit frequency across population density category were small relative to differences across dialysis facility size (Appendix Table A2).

Statistical methods

Due to large population size, we used a 10% standardized difference as a marker of heterogeneity when comparing differences in characteristics between treatment groups.25 In all difference-in-difference analyses, we used logistic regression to estimate odds ratios (OR) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI). We controlled for regional differences in population density and dialysis facility size, as well as patient age, sex, race, ethnicity, and medical comorbidities listed in Table 1.26 We did not adjust for dialysis facility characteristics, since the facility where a patient receives dialysis is often a consequence of dialysis modality choice. An interaction term between binary variables representing the start of dialysis before versus after payment reform, and whether patients were in the “treatment” or “control” group, estimated the effect of the policy on the odds of dialysis modality choice for each comparison.

Exhibit 1.

Baseline Characteristics of “Insurance Coverage” Cohort:

| Pre-Reimbursement Reform | Post-Reimbursement Reform | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medicare Advantage |

Traditional Medicare |

std diff |

Medicare Advantage |

Traditional Medicare |

std diff |

|

| (n=18,754) | (n=94,615) | (n=22,473) | (n=105,269) | |||

| Demographic | ||||||

| Age - years | 75.2 | 75.2 | 0.4 | 75.6 | 75.5 | 1.1 |

| Male - % | 53.4 | 50.4 | 6.0 | 54.3 | 52.4 | 3.9 |

| American Indian - % | 0.3 | 0.9 | 7.4 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 7.2 |

| Black - % | 20.8 | 22.4 | 3.7 | 22.4 | 21.2 | 2.8 |

| White - % | 73.7 | 73.8 | 0.3 | 72.3 | 74.8 | 5.6 |

| Other race - % | 5.2 | 3.0 | 11.4 | 5.0 | 3.1 | 9.8 |

| Hispanic ethnicity - % | 12.3 | 7.5 | 16.5 | 12.7 | 7.9 | 16.1 |

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| Diabetes - % | 49.3 | 50.9 | 3.2 | 52.6 | 51.8 | 1.6 |

| Coronary disease - % | 34.6 | 38.0 | 6.9 | 31.1 | 34.8 | 7.9 |

| Cancer - % | 8.0 | 8.8 | 2.9 | 9.0 | 10.1 | 3.7 |

| Heart failure - % | 37.0 | 40.6 | 7.3 | 39.8 | 42.0 | 4.5 |

| Pulmonary disease - % | 9.0 | 11.0 | 6.7 | 10.1 | 12.4 | 7.3 |

| Cerebrovascular disease - % | 11.2 | 12.5 | 4.2 | 11.5 | 12.4 | 2.8 |

| Peripheral vascular disease - % | 15.9 | 18.7 | 7.4 | 16.3 | 19.0 | 7.0 |

| Hemoglobin - g/dl± | 10.2 | 10.1 | 2.8 | 10.3 | 10.3 | 1.9 |

| Serum albumin g/dl± | 3.2 | 3.2 | 8.0 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 8.6 |

| BMI kg/m2± | 26.2 | 26.5 | 4.7 | 27.1 | 27.2 | 0.5 |

| Smoking history - % | 2.6 | 3.2 | 3.7 | 2.9 | 3.6 | 3.9 |

| Immobility - % | 4.1 | 5.0 | 4.4 | 6.5 | 7.3 | 3.2 |

| Drug or alcohol use - % | 0.6 | 0.7 | 1.3 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.8 |

| Geographic | ||||||

| Rural or small town | 2.3 | 12.3 | 37.2 | 3.8 | 12.3 | 30.8 |

| Area with larger facilities | 93.5 | 88.5 | 20.9 | 92.3 | 88.6 | 14.0 |

Note: 1,946 patients were excluded from this analysis because their zip codes could not be linked to hospital referral regions.

Among patients included in the analysis, hemoglobin was missing in 8.4% of the population; serum albumin was missing in 25% of the population; BMI was missing in 1.1% of the population. 0.1% of patients had missing values for either age, sex, drug or alcohol abuse, or population density. All missing values were imputed.

We used our logistic regression estimates to determine the effect of physician reimbursement reform on the absolute probability of home dialysis use. For each patient in the relevant cohort, we calculated four predicted probabilities of home dialysis use assuming he was in each comparison group both before and after the policy. We used these predicted probabilities to calculate a difference-in-difference estimate of the policy effect for each patient. (See appendix) We averaged the individual policy effect estimates over all patients, and used the delta method to calculate standard errors and 95% confidence intervals around average predicted probability estimates.

In a secondary analysis, we explored how different patients were affected by the policy. We separated selected categories of patients by dialysis facility size comparison group. For each patient category, we determined the unadjusted change in proportion of patients assigned to home dialysis following payment reform stratified by dialysis facility size.

RESULTS

The cohort of patients with Traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage (insurance coverage cohort) included 241,111 patients. Before payment reform, 18,754 (16.5%) and 94,615 (83.5%) of patients had Medicare Advantage and Traditional Medicare, respectively, compared to 22,473 (17.6%) and 105,269 (82.4%) after the reform. Among patients with Traditional Medicare, 5.8% and 5.0% of patients were assigned to home dialysis before and after payment reform, respectively. Corresponding figures for patients with Medicare Advantage were 4.5% and 4.3%. Patient characteristics, were similar across insurance category, except more patients with Medicare Advantage were Hispanic and fewer lived in rural areas and small towns. (Table 1)

The cohort of patients with Traditional Medicare or waiting for Medicare coverage (Non-HMO Medicare cohort) included 389,526 patients. Before payment reform, 19,685 (10.8%) and 163,415 (89.2%) of patients lived in areas with smaller and larger facilities, respectively, compared to 21,840 (10.6%) and 184,586 (89.4%) after the reform. Among patients living in areas with smaller facility sizes, 6.7% were assigned to home dialysis both prior to and following payment reform. Among patients living in areas with larger facility sizes, 6.5% were assigned to home dialysis prior to payment reform compared to 5.5% following payment reform. There were no significant differences in co-morbidities among patients receiving dialysis in areas with different facility sizes, while more whites and American Indians lived in areas with smaller facilities, and more blacks and Hispanics lived in areas with larger facilities. Smaller facilities were more likely to be in rural areas and small towns. (Table 2)

Table 2.

Baseline Characteristics of Dialysis Facility Size Comparison in the “Non-HMO Medicare” Cohort.

| Pre-Reimbursement Reform | Post-Reimbursement Reform | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Larger Facility |

Small Facility |

std diff |

Larger Facility |

Small Facility |

std diff |

|

| (n=163,415) | (n=19,685) | (n=184,586) | (n=21,840) | |||

| Demographic | ||||||

| Age – years | 62.8 | 64.0 | 7.4 | 63.0 | 64.1 | 7.4 |

| Male - % | 53.4 | 54.2 | 1.7 | 55.1 | 55.0 | 0.1 |

| American Indian - % | 1.1 | 3.1 | 14.2 | 1.0 | 3.1 | 14.4 |

| Black - % | 31.8 | 19.4 | 29.7 | 31.0 | 18.9 | 29.3 |

| White - % | 63.3 | 76.1 | 25.5 | 64.0 | 76.5 | 25.0 |

| Other race - % | 3.9 | 1.4 | 15.8 | 4.0 | 1.5 | 15.2 |

| Hispanic ethnicity - % | 11.5 | 2.8 | 34.3 | 12.1 | 3.1 | 35.0 |

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| Diabetes - % | 51.9 | 50.1 | 3.8 | 53.1 | 52.2 | 1.9 |

| Coronary disease - % | 27.7 | 31.5 | 8.3 | 25.1 | 29.2 | 9.2 |

| Cancer - % | 6.0 | 6.8 | 3.5 | 6.8 | 7.9 | 4.5 |

| Heart failure - % | 32.4 | 33.7 | 2.8 | 33.8 | 35.3 | 3.1 |

| Pulmonary disease - % | 7.8 | 9.9 | 7.2 | 8.8 | 11.1 | 7.7 |

| Cerebrovascular disease - % | 9.6 | 11.0 | 4.5 | 9.7 | 10.9 | 3.8 |

| Peripheral vascular disease - % | 14.3 | 17.9 | 9.7 | 14.6 | 18.0 | 9.3 |

| Hemoglobin - g/dl± | 9.9 | 10.1 | 9.4 | 10.1 | 10.2 | 9.7 |

| Serum albumin g/dl± | 3.1 | 3.1 | 1.6 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 4.7 |

| BMI kg/m2± | 27.6 | 27.9 | 4.3 | 28.3 | 28.6 | 4.0 |

| Smoking history - % | 5.1 | 6.6 | 6.2 | 5.9 | 7.3 | 5.8 |

| Immobility - % | 3.9 | 3.9 | 0.3 | 5.6 | 5.2 | 1.5 |

| Drug or alcohol use - % | 1.9 | 1.5 | 2.8 | 2.2 | 1.9 | 2.2 |

| Geographic | ||||||

| Rural or small town | 9.7 | 27.2 | 43.0 | 9.8 | 27.0 | 42.3 |

Note: 2,402 patients were excluded from this analysis because their zip codes could not be linked to hospital referral regions. This cohort differs from the group of patients with Traditional Medicare coverage in the “Insurance Coverage” cohort in two ways. First, it includes patients of all ages at onset of dialysis. Second, it includes patients documented as “waiting” for Medicare coverage at the onset of dialysis.

Among patients included in the analysis, a total of 8.4% had missing hemoglobin; 25% missing serum albumin, and; 1.1% missing BMI. 0.1% of patients had missing values for either age, drug or alcohol abuse, or population density. All missing values were imputed.

Applying a difference-in-difference regression model, patients with Traditional Medicare coverage (who were affected by the policy) experienced a 12% (95% CI, 2%–21%) reduction in the odds of home dialysis following payment reform when compared to patients with Medicare Advantage (who were not affected by the policy). (Appendix Table A3) This corresponds to a 0.7% (95% CI 0.2%–1.1%; p=0.003) reduction in the average absolute probability of home dialysis use following payment reform among patients with Traditional Medicare compared to patients with Medicare Advantage. (Table 3)

Table 3.

Average Probability of Home Dialysis from Regression Models:

| Insurance Coverage Comparison Groups | ||||||

| Medicare Advantage | Traditional Medicare | |||||

| probability of home dialysis |

LCI | UCI | probability of home dialysis |

LCI | UCI | |

| Prior to reimbursement reform | 4.5 | 4.2 | 4.8 | 5.8 | 5.7 | 6.0 |

| Following reimbursement reform | 4.2 | 4.0 | 4.5 | 4.9 | 4.8 | 5.1 |

| Difference following reform | −0.2 | −0.6 | 0.1 | −0.9 | −1.1 | −0.7 |

| Policy Effect (%) | LCI | UCI | ||||

| Difference-in-difference estimate* | 0.7 | 0.2 | 1.1 | |||

| Dialysis Facility Size Comparison Groups | ||||||

| Areas with small facilities | Areas with larger facilities | |||||

| probability of home dialysis |

LCI | UCI | probability of home dialysis |

LCI | UCI | |

| Prior to reimbursement reform | 5.8 | 5.5 | 6.2 | 6.6 | 6.5 | 6.7 |

| Following reimbursement reform | 5.8 | 5.5 | 6.1 | 5.6 | 5.5 | 5.7 |

| Difference following reform | −0.1 | −0.5 | 0.3 | −1.0 | −1.2 | −0.8 |

| Policy Effect (%) | LCI | UCI | ||||

| Difference-in-difference estimate‡ | 0.9 | 0.5 | 1.4 | |||

p=0.003

p<0.001

Note: UCI and LCI are the upper and lower bounds of the 95% confidence interval, respectively. An examination of the sensitivity of our findings to possible geographic clustering in dialysis modality choice using generalized estimating equation models was not substantially different from our primary study results. (Table A5)

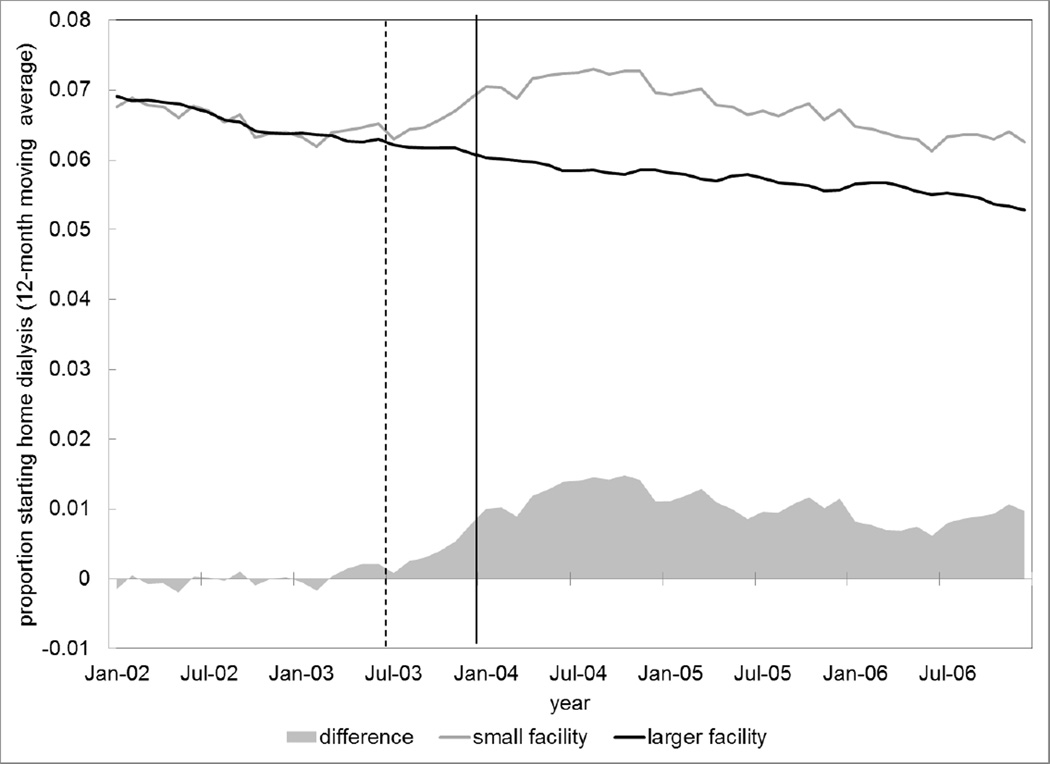

Patients living in areas with larger dialysis facilities (where physicians could increase revenues from in-center dialysis at lower cost) experienced a 16% reduction in the odds of provision of home dialysis (95% CI, 8%–22%) compared to patients living in areas with smaller facilities (where it was less lucrative to visit patients receiving in-center dialysis). (Appendix Table A4) This corresponds to a 0.9% (95% CI 0.5%–1.4%; p<0.001) reduction in the average absolute probability of home dialysis use following payment reform among patients living in areas with larger facilities compared to patients living in areas with smaller facilities. (Table 3) Figure 1 illustrates the unadjusted change in modality choice among patients residing in areas with different dialysis facility sizes. There was no significant effect of the policy in our analysis of population density.

Figure 1. Dialysis Modality Assignment over Time in Areas with Small versus Larger Dialysis Facilities.

Note: Dashed line represents the reimbursement reform proposed rule; solid line represents the final rule. Probabilities are unadjusted. A plot of probabilities adjusted for covariates from our primary regression model is not substantively different.

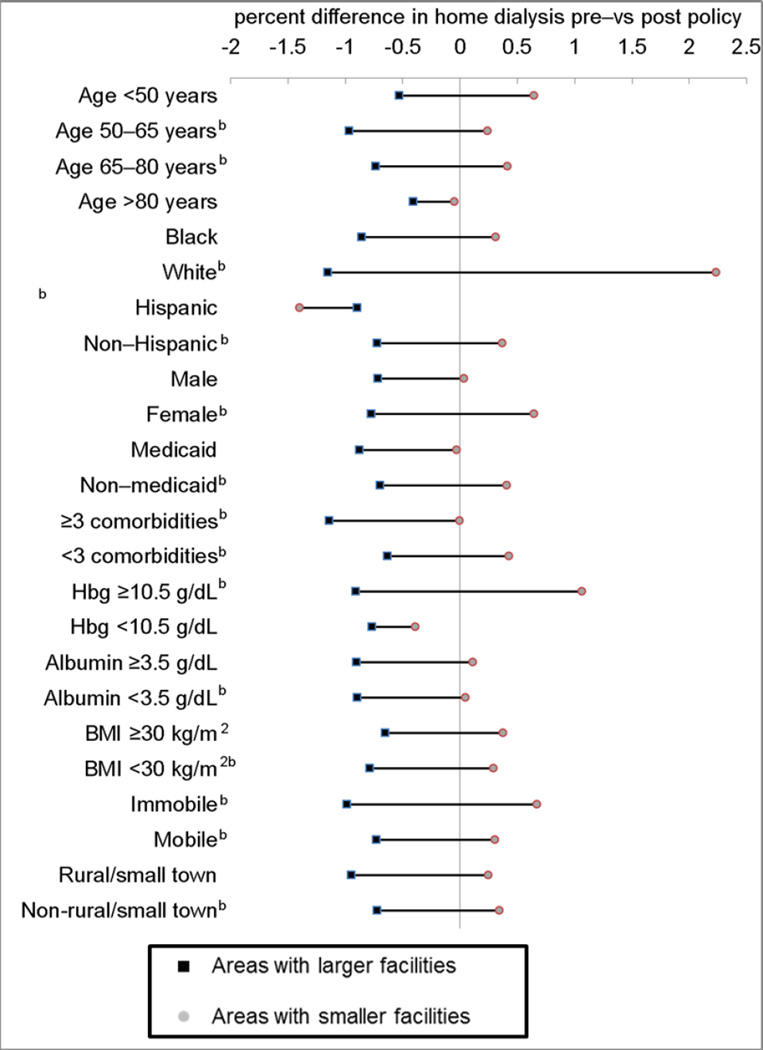

Nearly all patient groups living in areas with larger facilities were less likely to receive home dialysis following physician payment reform. Among patients living in areas with smaller facilities, women, whites, patients with hemoglobin >10.5 g/dL, and immobile patients appeared more likely to receive home dialysis following payment reform. (Figure 2)

Figure 2. Change in Dialysis Modality Following Payment Reform by Dialysis Facility Sizes and Selected Patient Characteristics.

Note: bre a statistically significant difference (p<0.01) in the change in use of home dialysis between areas with large and smaller facilities. Analyses are unadjusted.

DISCUSSION

We found that the 2004 Medicare reform to physician dialysis visit payments led to a reduction in use of home dialysis. Patients who were most affected by the policy, either because they were insured by Traditional Medicare or because they lived in areas where physicians could increase in-center hemodialysis revenues at lower cost, experienced nearly a 1% absolute reduction in the probability of receiving home dialysis compared to patients who were unaffected (or less affected) by the policy. More specifically, approximately 8 out of every 1,000 patients initiating dialysis who were affected by the policy received in-center hemodialysis rather than home dialysis as a result of the policy. The payment policy appeared to have influenced dialysis modality choice for nearly all patient groups, regardless of sex, race, ethnicity, or overall health.

According to statements from CMS, the 2004 physician payment reform was designed to align economic incentives and improve the quality of dialysis care.27 In the discourse leading up to the policy’s enactment, there was no mention of how the reform might influence dialysis modality decisions. Since the policy was enacted, some physicians have expressed concern that the policy created a financial incentive to place some patients on in-center hemodialysis rather than home hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis.28 Yet, surveys of nephrologists in the US suggest that economic factors do not play an important role in dialysis modality selection.11,15 Our findings indicate that economic incentives have had a substantial effect on physicians’ decisions regarding dialysis modality, and that payment reform had the unintended consequence of leading fewer patients to home dialysis. Since the choice of dialysis modality is central to patients’ quality of life, independence, and healthcare costs, a reduction in the use of home dialysis can be seen as a failure of the policy.8,29,30 Recently, reform to Medicare dialysis facility reimbursement (the 2011 ESRD PPS) encourages greater use of home dialysis, and has coincided with a trend back towards greater use of peritoneal dialysis.3,14

Pay-for-performance (P4P) initiatives have been proposed as a solution to problems in healthcare by encouraging the delivery of high-value care.31,32 Small trials and demonstration projects suggest that P4P initiatives may lead to high-quality care.33,34 Yet, the overall efficacy of P4P programs remains uncertain, and a number of studies have demonstrated important unintended consequences.35 Due to mandates from the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, CMS plans to expand the scope of its P4P initiative on a national scale with a program directed at physician payments deemed the Physician Value-based Payment Modifier.36 The recent repeal of Medicare’s Sustainable Growth Rate formula calls for additional programs directed at physician payment.2 Because it was, in part, designed to improve the quality of care, the 2004 physician payment reform is an early example of a national P4P program directed at physician behavior. Despite evidence that more frequent hemodialysis visits are associated with some favorable health outcomes,37–40 policy analyses have failed to demonstrate any benefit and suggest that healthcare costs increased.41,42

Our findings appear to contrast with physician surveys indicating that economic factors do not influence dialysis modality decisions. However, these seemingly disparate findings can be reconciled. For a given physician, or group of physicians practicing in geographic proximity, the net financial reward from in-center versus home dialysis is a function of facility sizes and insurance composition (i.e., the fraction of patients with Traditional Medicare versus Medicare Advantage) among other factors. To the extent that dialysis facility characteristics and patients with Medicare Advantage are clustered geographically, regional differences in practice patterns may reflect underlying economic incentives even if individual physicians do not base their dialysis modality recommendations on economic grounds.

This study has several limitations. Although we use “control” groups for comparison and multivariable adjustment to reduce the potential for bias, we cannot fully exclude the possibility that unobserved factors differentially affected changes in modality choice across comparison groups. For example, unobserved changes over time in patients’ suitability for home dialysis, willingness to administer dialysis at home, or preparation for dialysis that differentially affected one comparison group could lead to bias. Additionally, the relative financial gain for physicians of in-center versus home dialysis care may have influenced dialysis modality decisions for some patients receiving Medicare Advantage through a “spillover” effect, leading us to underestimate the effect of payment reform. Finally, small variation in visit frequency associated with nephrologist and geographic density may have prevented us from observing significant effects of these factors on dialysis modality choice.

In conclusion, we found that national physician payment reform enacted by CMS in 2004 in an effort to encourage more frequent face-to-face dialysis visits and improve the quality of care resulted in an unintended consequence of relatively fewer patients choosing home dialysis. The tiered fee-for-service payment system enacted in 2004 continues to govern physician reimbursement for dialysis care, and consequently, may continue to discourage home dialysis use in certain patient populations. These findings highlight both an area of policy failure and the importance of considering unintended consequences of future efforts to reform physician payment.

Supplementary Material

Take Away Points.

In 2004, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services reformed physician payment for in-center hemodialysis care from a capitated to tiered fee-for-service model, augmenting physician payment for frequent in-center visits. This policy may have influenced home dialysis use by making in-center dialysis more lucrative for some physicians. We compared home dialysis use among patients differentially affected by the policy.

Patients most affected by the policy experienced nearly a 1% reduction in the absolute probability of home dialysis use following payment reform.

Our findings indicate that transition to fee-for-service payment for dialysis had the unintended consequence of reducing home dialysis use.

Acknowledgments

Author Access to Data: This work was conducted under a data use agreement between Dr. Winkelmayer and the National Institutes for Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIKKD). An NIDDK officer reviewed the manuscript and approved it for submission. The data reported here have been supplied by the United States Renal Data System (USRDS). The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the author(s) and in no way should be seen as an official policy or interpretation of the U.S. government.

Funding: F32 HS019178 from AHRQ (Dr. Erickson); DK085446 (Dr. Chertow); Dr. Winkelmayer receives research and salary support through the endowed Gordon A. Cain Chair in Nephrology at Baylor College of Medicine. Dr. Bhattacharya would like to thank the National Institute on Aging for support for his work on this paper (R37 150127-5054662-0002).

REFERENCES

- 1.Burwell SM. Setting value-based payment goals--HHS efforts to improve U.S. health care. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015 Mar 5;372(10):897–899. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1500445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steinbrook R. The Repeal of Medicare's Sustainable Growth Rate for Physician Payment. JAMA. 2015;313(20) doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.4550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.USRDS. Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.King K. Patients' perspective of factors affecting modality selection: a National Kidney Foundation patient survey. Advances in Renal Replacement Therapy. 2000 Jul;7(3):261–268. doi: 10.1053/jarr.2000.8123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boateng EA, East L. The impact of dialysis modality on quality of life: a systematic review. Journal of Renal Care. 2011 Dec;37(4):190–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-6686.2011.00244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rubin HR, Fink NE, Plantinga LC, Sadler JH, Kliger AS, Powe NR. Patient ratings of dialysis care with peritoneal dialysis vs hemodialysis. JAMA. 2004 Feb 11;291(6):697–703. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.6.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cameron JI, Whiteside C, Katz J, Devins GM. Differences in quality of life across renal replacement therapies: a meta-analytic comparison. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2000 Apr;35(4):629–637. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(00)70009-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morton RL, Tong A, Howard K, Snelling P, Webster AC. The views of patients and carers in treatment decision making for chronic kidney disease: systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. BMJ. 2010;340:c112. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blake PG, Quinn RR, Oliver MJ. Peritoneal dialysis and the process of modality selection. Peritoneal Dialysis International. 2013 May-Jun;33(3):233–241. doi: 10.3747/pdi.2012.00119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.System USRD. The USRDS Dialysis Morbidity and Mortality Study: Wave 2. 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mendelssohn DC, Mullaney SR, Jung B, Blake PG, Mehta RL. What do American nephologists think about dialysis modality selection? American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2001 Jan;37(1):22–29. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2001.20635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heaf J. Underutilization of peritoneal dialysis. JAMA. 2004 Feb 11;291(6):740–742. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.6.740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nissenson AR, Prichard SS, Cheng IKP, et al. ESRD Modality Selection Into the 21st Century: The Importance of Non Medical Factors. ASAIO Journal May/June. 1997;43(3):143–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rivara MB, Mehrotra R. The changing landscape of home dialysis in the United States. Current Opinion in Nephrology & Hypertension. 23(6):586–591. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0000000000000066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thamer M, Hwang W, Fink NE, et al. US nephrologists' recommendation of dialysis modality: results of a national survey. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2000 Dec;36(6):1155–1165. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2000.19829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Services DoHaHRCfMaM. Physician Fee Schedule. [Accessed June, 2011];2011 http://www.cms.gov/apps/physician-fee-schedule/overview.aspx.

- 17.CMS. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; Department of Health and Human Services, editor. Medicare Program; Revisions to Payement Policies Under the Physician Fee Schedule for Calendar Year 2004; Proposed Rule. 2003;68:20–22. [Google Scholar]

- 18.ME M-R, WC W, M D. Addressing Missing Data in Clinical Studies of Kidney Diseases. Clinical Journal of The American Society of Nephrology: CJASN. 2014 doi: 10.2215/CJN.10141013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buuren SV, Brands JPL, Groothuis-Oudshoorn CGM, Rubin DB. Fully Conditional Specification in Multivariate Imputation. Journal of Statistical Computation and Simulation. 2006 Dec;76(12):1049–1064. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Little R, Rubin D. Statistical Analysis with Missing Data. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rural-Urban Commuting Area Codes (RUCA) WWAMI Rural Health Research Center. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Practice TDIfHPaC. Selected Hospital and Physician Capacity Measures. [Accessed 6/1/2012, 2012];2006 http://www.dartmouthatlas.org/tools/downloads.aspx#resources. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Methods for evaluating changes in health care policy: the difference-in-differences approach. JAMA. 2014 Dec 10;312(22):2401–2402. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.16153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Erickson KF, Tan KB, Winkelmayer WC, Chertow GM, Bhattacharya J. Variation in Nephrologist Visits to Patients on Hemodialysis across Dialysis Facilities and Geographic Locations. Clinical Journal of The American Society of Nephrology: CJASN. 2013;8(6):987–994. doi: 10.2215/CJN.10171012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Austin PC. Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity-score matched samples. Statistics in Medicine. 2009 Nov 10;28(25):3083–3107. doi: 10.1002/sim.3697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stack AG. Determinants of modality selection among incident US dialysis patients: results from a national study. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 13(5):1279–1287. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1351279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Centers for M, Medicaid Services HHS. Medicare program; revisions to payment policies under the physician fee schedule for calendar year 2004. Final rule with comment period. Federal Register. 2003 Nov 7;68(216):63195–63395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Just PM, de Charro FT, Tschosik EA, Noe LL, Bhattacharyya SK, Riella MC. Reimbursement and economic factors influencing dialysis modality choice around the world. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2008 Jul;23(7):2365–2373. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hirth RA, Chernew ME, Turenne MN, Pauly MV, Orzol SM, Held PJ. Chronic illness, treatment choice and workforce participation. International Journal of Health Care Finance & Economics. 2003 Sep;3(3):167–181. doi: 10.1023/a:1025332802736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berger A, Edelsberg J, Inglese GW, Bhattacharyya SK, Oster G. Cost comparison of peritoneal dialysis versus hemodialysis in end-stage renal disease. American Journal of Managed Care. 2009 Aug;15(8):509–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Talavera JA, Broadhead P, Dudley RA. A behavioral model of clinician responses to incentives to improve quality. Health Policy. 2007 Jan;80(1):179–193. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Epstein AM, Lee TH, Hamel MB. Paying physicians for high-quality care. New England Journal of Medicine. 2004 Jan 22;350(4):406–410. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb035374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang JJ, De Leon SF, Shih SC, Boscardin WJ, Goldman LE, Dudley RA. Effect of pay-for-performance incentives on quality of care in small practices with electronic health records: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2013 Sep 11;310(10):1051–1059. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.277353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simpson K, Pietz K, Urech TH, et al. Effects of individual physician-level and practice-level financial incentives on hypertension care: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2013 Sep 11;310(10):1042–1050. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.276303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Damberg C, Sorbero M, Lovejoy S, Martsolf G, Raaen L, Mandel D. Measuring Success in Health Care Value-Based Purchasing Programs. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2014. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Services CfMM. Value-Based Payment Modifier. [Accessed 1/14/2015, 2015];Medicare FFS Physician Feedback Program/Value Based Payment Modifier. 2014 http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/PhysicianFeedbackProgram/ValueBasedPaymentModifier.html.

- 37.McClellan WM, Soucie JM, Flanders WD. Mortality in end-stage renal disease is associated with facility-to-facility differences in adequacy of hemodialysis. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 1998 Oct;9(10):1940–1947. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V9101940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Plantinga LC, Jaar BG, Fink NE, et al. Frequency of patient-physician contact in chronic kidney disease care and achievement of clinical performance targets. International Journal for Quality in Health Care. 2005 Apr;17(2):115–121. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzi010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Erickson KF, Winkelmayer WC, Chertow GM, Bhattacharya J. Physician Visits and 30-Day Hospital Readmissions in Patients Receiving Hemodialysis. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2014 doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013080879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Erickson KF, Mell M, Winkelmayer WC, Chertow GM, Bhattacharya J. Provider Visits and Early Vascular Access Placement in Maintenance Hemodialysis. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2014 doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014050464. 2014(Published ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Erickson KF, Winkelmayer WC, Chertow GM, Bhattacharya J. Medicare Reimbursement Reform for Provider Visits and Health Outcomes in Patients on Hemodialysis. Forum for Health Economics & Policy. 2014;0(0):1558–9544. doi: 10.1515/fhep-2012-0018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mentari EK, DeOreo PB, O'Connor AS, Love TE, Ricanati ES, Sehgal AR. Changes in Medicare reimbursement and patient-nephrologist visits, quality of care, and health-related quality of life. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2005 Oct;46(4):621–627. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.