Abstract

Background

Prospective data suggest depressive symptoms worsen insulin resistance and accelerate type 2 diabetes (T2D) onset.

Purpose

We sought to determine if reducing depressive symptoms in overweight/obese adolescents at-risk for T2D would increase insulin sensitivity and mitigate T2D risk.

Method

We conducted a parallel-group randomized controlled trial comparing a 6-week cognitive-behavioral (CB) depression prevention group with a 6-week health education (HE) control group in 119 overweight/obese adolescent girls with mild-to-moderate depressive symptoms (Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale [CES-D] ≥16) and T2D family history. Primary outcomes were baseline to post-intervention changes in CES-D and Whole Body Insulin Sensitivity Index (WBISI), derived from 2-hour oral glucose tolerance tests. Outcome changes were compared between groups using ANCOVA, adjusting for respective baseline outcome, puberty, race, facilitator, T2D family history degree, baseline age, adiposity, and adiposity change. Multiple imputation was used for missing data.

Results

Depressive symptoms decreased (p<0.001) in CB and HE from baseline to post-treatment, but did not differ between groups (ΔCESD −12 vs. −11, 95% CI difference −4 to +1, p=0.31). Insulin sensitivity was stable (p>0.29) in CB and HE (ΔWBISI 0.1 vs. 0.2, 95% CI difference −0.6 to +0.4, p=0.63). Among all participants, reductions in depressive symptoms were associated with improvements in insulin sensitivity (p=0.02).

Conclusions

Girls at-risk for T2D displayed reduced depressive symptoms following 6 weeks of CB or HE. Decreases in depressive symptoms related to improvements in insulin sensitivity. Longer-term follow-up is needed to determine if either program causes sustained decreases in depressive symptoms and improvements in insulin sensitivity.

Keywords: Adolescence, Depression, Insulin Resistance, Type 2 Diabetes, Randomized Controlled Trial

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is one of the most common obesity-related chronic diseases and a leading cause of severe health complications, including cardiovascular and peripheral vascular disease and stroke (1). Forty percent of individuals in the U.S. are estimated to develop T2D in their lifetimes, with higher estimates for racial/ethnic minorities including African Americans, Hispanics, and American Indians (2). Although once a disease limited to older adults, T2D incidence in adolescents and young adults is escalating (3), making effective, early preventative efforts an imperative.

Depression, also a major public health problem, has gained increasing attention for its role in obesity- and diabetes-related health outcomes (4). Prevalence of elevated depressive symptoms or major depressive disorder (MDD) is two- to three-fold higher among adolescents and adults with T2D compared to community samples or individuals with type 1 diabetes (5, 6). In adults with T2D, co-morbid elevated depressive symptoms are associated with poorer glycemic control, incident retinopathy, higher odds of adverse micro- and macrovascular events, greater cognitive decline, and greater mortality (7). Moreover, adults’ elevated depressive symptoms or MDD prospectively predict future onset of T2D, adjusting for body weight or adiposity (8). Similarly, children’s and adolescents’ depressive symptoms are positively associated cross-sectionally with fasting insulin and insulin resistance—a key precursor to T2D (9)—independent of degree of overweight (10–13). Further, children’s depressive symptoms predict worsening insulin resistance over time, even when correcting for initial BMI and BMI gain (14).

It remains unclear if depressive symptoms play a causal role in worsening insulin resistance, because the majority of extant data are correlational. Among individuals without diabetes, MDD is associated with insulin resistance (15), an abnormality that can be resolved after depression treatment without significant change in BMI (16). Among adults with MDD and T2D, systematic reviews and a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials find significant effects of psychotherapy and pharmacological treatment of depression on MDD remission and mood improvements, with varied effects on glycemic control (17).

However, it is unknown whether reducing depressive symptoms during adolescence would ameliorate insulin resistance, and consequently, mitigate at-risk adolescents’ odds of developing T2D. We, therefore, conducted a randomized controlled trial with the primary aim of evaluating if decreasing depressive symptoms would improve insulin sensitivity among overweight/obese adolescent girls at-risk for T2D. The primary hypothesis was that decreasing depressive symptoms would ameliorate insulin sensitivity. As an exploratory aim, we also sought to evaluate to what degree eating, physical fitness, and cortisol response—potential factors that have been put forth to explain the depression-insulin association (18–24)—were impacted by a depression prevention intervention delivered to girls at-risk for T2D with mild-to-moderate depressive symptoms. We hypothesized that participation in an intervention that decreased depressive symptoms would also decrease energy intake, improve fitness, and enhance cortisol reactivity to stress.

Method

Participants

One-hundred nineteen adolescent girls, 12–17 years, were recruited for a T2D prevention trial. Recruitment materials were targeted to parents who were concerned about their daughter developing T2D and who were interested in having her participate in a brief group to lower diabetes risk. Participants were recruited through the National Institutes of Health clinical trials website, local area community postings, letters/flyers to physician offices and schools, advertisements in school parent and community e-mail listserves, advertisements in local area newspapers, metro/buses, public radio stations, church/synagogue bulletins, and direct mailings to homes within a 60-mile radius of Bethesda, Maryland. Inclusion criteria were: (i) female, (ii) 12–17 years, (iii) overweight/obesity (BMI ≥85th percentile for age), (iv) a history of T2D, prediabetes, or gestational diabetes in ≥1 first- or second-degree relative, (v) good general health, (vi) the ability to speak and understand spoken English (because the groups were facilitated in English), and (vii) mild-to-moderate depressive symptoms as indicated by a total score ≥16 on the 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D; 25). Our original cut-off for the CES-D was >20; we modified it based upon a lower cut-point (≥16) utilized in some prior adolescent depression prevention work (11) and in order to increase the pool of eligible participants. Exclusion criteria were: (i) current psychiatric symptoms that necessitated treatment (e.g., MDD, bipolar disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, social anxiety disorder, substance abuse, conduct disorder, or psychosis, as well as active suicidal ideation or suicidal behavior), as determined by clinical interview, (ii) a major medical problem including T2D (fasting glucose level >126 mg/dL or 2-hour glucose after an oral glucose administration >200 mg/dL), (iii) medication use that could affect insulin resistance, body weight, or mood (e.g., insulin sensitizers, anti-depressants, or stimulants), (iv) current involvement in structured weight loss or psychotherapy, and (v) pregnancy. Girls who were not living with a biological parent (e.g., adopted or in foster care) were eligible for participation as long as a guardian could provide consent and health information about the biological family history of diabetes. Informed consent and assent were obtained in writing from parents/guardians and adolescents, respectively. The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Institutional Review Board approved all procedures. Participants were compensated for participation.

Study Design and Procedures

The study was a parallel-group, randomized controlled trial comparing the effects of participation in a cognitive-behavioral (CB) depression selective prevention group with the effects of participation in a health education (HE) control group. All assessment and intervention sessions took place in an outpatient pediatric clinic at the National Institutes of Health Mark O. Hatfield Clinical Research Center in Bethesda, Maryland. After a phone screen to evaluate potential eligibility, participants and their parent/guardian attended an outpatient visit to provide informed assent/consent, to determine eligibility, and to collect baseline assessments. Eligible participants were randomized to either the 6-week CB group or the 6-week HE group. Randomization was stratified by age (12–14 years, 15–17 years) and race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Other). Randomization strings were generated by an electronic program with permuted blocks. Groups were run in parallel on weekdays during after-school hours, with a total of 3 to 8 girls in each group. The CB and HE groups were conducted in separate outpatient clinics to ensure no cross-contamination between conditions.

Experimental Groups

CB Program

The CB group was a manualized, selective depression prevention program consisting of 1-hour sessions, once per week, for 6 weeks (26, 27). As a selective intervention, this program was designed for adolescents with elevated depressive symptoms. The program has demonstrated efficacy in decreasing depressive symptoms and reducing MDD incidence in adolescents up to two years following program participation (26, 27). Sessions are highly interactive and activity-based to maximize engagement. Motivational enhancement is used throughout the program to encourage participation in sessions and completion of homework. For instance, facilitators ask participants to list the advantages of and potential barriers to group attendance and homework completion and to generate solutions for any barriers. The first session includes a review of the rationale and format, introduction to the interconnectedness of feelings, thoughts, and behaviors, instruction in self-monitoring, and psychoeducation on cognitive restructuring and pleasant activities. The second and third sessions focus upon challenging maladaptive thoughts, making positive self-statements, and self-reinforcement. The fourth session teaches positive coping skills for negative events. The fifth and sixth sessions concentrate on coping with future daily hassles and major life stressors. Feelings about termination are discussed briefly in the final group. At all sessions, adolescents are assigned homework, including completion of a daily mood journal and engagement in pleasant activities, to reinforce and apply concepts learned in the sessions to their daily lives. Twenty percent of sessions were reviewed by a non-investigator expert (Heather Shaw, Ph.D.) for facilitator competence and program fidelity. We made no adaptations to the CB manual (26). The intervention was co-facilitated by a clinical psychologist and a psychology graduate student trained in the program’s administration by a developer (Eric Stice, Ph.D.).

HE Program

The HE group program was derived from a middle and high school health education curriculum (28), which we manualized and have used as a control group in other clinical trials (29, 30). In the current manualized adaptation, in order to match CB for time, attention, and facilitator expertise, participants in HE met for 1-hour sessions, once per week for 6 weeks, and the programs were co-facilitated by a clinical psychologist and psychology graduate student. The curriculum included six weekly topics: i) alcohol and drug use, ii) nutrition/body image, iii) domestic violence, iv) sun safety, v) exercise, and vi) identifying MDD/suicide risk. The program was didactic, incorporating presentations, handouts, and videos. The depression and suicide module focused exclusively on prevalence of these problems, their relation to other health issues, and how to identify signs of MDD and suicide. No direct counseling advice was provided during the HE program, other than in the event of a psychiatric crisis or suicidal ideation, in which case a treatment referral was facilitated.

To control for potential facilitator effects, interventionists (five psychologists) were trained in both the CB and HE manualized programs. Across the study, all leaders facilitated cohorts assigned to both the CB and the HE groups, so that by the end of the study, each leader had facilitated an approximately equal number of CB and HE 6-session groups. Eleven cohorts of adolescents participated between September 2011 and July 2014. To verify that the HE content did not overlap with the CB program, a randomly selected subset of 15–20% of HE sessions were audiotaped and evaluated for CB content by a psychologist with expertise in the CB program.

Medical Information

A nurse practitioner or endocrinologist conducted a medical history and physical to determine family history of diabetes and to rule out any major adolescent medical problem that would result in study exclusion. Breast development was assessed by physical inspection and palpitation, and breast maturation was assigned according to the five stages of Tanner (31).

Outcome Measures

All measurements were collected at baseline and repeated at an immediate post-treatment outpatient assessment, within two weeks of group completion. Assessors of all key outcomes were blind to group assignment.

Anthropometrics

Participant’s weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg with a calibrated digital scale. Height was determined with a calibrated wall stadiometer from the average of three measurements. BMI (weight in kg/[height in m2]) and BMI z were calculated according to CDC 2000 standards. Percent body fat was estimated with a bioelectrical impedance body composition analyzer (model Quantum II, RJL Systems, Detroit, Michigan), conducted by a trained dietitian or technician following manufacturer guidelines. For all body measures, participants were assessed in a fasted state with shoes removed.

Depressive Symptoms and Psychological Functioning

The total, sum score of the 20-item CES-D was used to determine study inclusion (criterion ≥16) and to provide a continuous measure of depressive symptoms (25). Scores of 16–20 are considered indicative of mild depressive symptoms; scores exceeding 20 are considered indicative of moderate depressive symptoms. Consistent with past approaches to selective depression prevention in adolescents (26), there was no upper limit to the CES-D. Instead, to determine the presence of MDD or another psychiatric disorder that would warrant study exclusion, the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children (K-SADS; 32) was administered by a trained interviewer. As in our prior studies (29, 30), we administered the adolescent-only portion of the K-SADS and assessed functioning over the past 12 months (as opposed to lifetime history of psychopathology). Interviewers participated in a series of training sessions with a developer (Joan Kaufman, Ph.D.) and expert (Daniel Pine, M.D.), and received ongoing monitoring and supervision by the lead author. The K-SADS has demonstrated adequate test-retest reliability, internal consistency, and predictive validity in adolescents (33), and in the current sample, demonstrated good inter-rater reliability for MDD diagnosis (k=0.89 on 20% of interviews). We excluded and facilitated referrals to an appropriate mental health professional for any adolescent who, as determined on the K-SADS, met criteria for current MDD or another psychiatric disorder that necessitated treatment.

OGTT

An OGTT was performed in the morning following an overnight fast initiated at 10:00 pm the previous evening. Participants received 1.75 g/kg of dextrose (maximum of 75 g). Blood was sampled for serum insulin and plasma glucose at fasting and at 30, 60, 90 and 120 minutes after dextrose administration. Insulin concentrations were determined using a commercially-available immunochemiluminometric assay purchased from Diagnostic Product Corporation, Los Angeles, California and calibrated against insulin reference preparation 66/304. The insulin assay used a monoclonal anti-insulin antibody and was run on an Immulite2000 machine (Diagnostic Product Corporation, Los Angeles, California). Plasma was collected in tubes containing powdered sodium fluoride and glucose was measured by the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center clinical laboratory using a Hitachi 917 analyzer (Roche Diagnostics Indianapolis, Indiana). These measures were used to estimate the Whole Body Insulin Sensitivity Index (WBISI; 34), calculated as 10,000 divided by the square root of the product of fasting glucose (mg/dL) and fasting insulin (mIU/mL) times the product of mean glucose0–120 (mg/dL) and mean insulin0–120 (mIU/mL). WBISI has been validated against euglycemic-hyperinsulinemic clamp-derived measures for use in overweight and obese youth (35). We also estimated insulin resistance with the homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) index, calculated as (fasting insulin [mIU/mL] × fasting glucose [mmol/L)/22.5 (36). We determined impaired fasting glucose (IFG; fasting glucose=100–125 mg/dL) and impaired glucose tolerance (IGT; 2-hour glucose=140–199 mg/dL).

Eating Behavior

Eating when hungry and eating in the absence of physiological hunger were measured at two successive test meals. After OGTT testing at 12:00 pm, each participant was served a large multi-item food array (>10,000 kcal), varied in macronutrients (55% carbohydrate, 12% protein, 33% fat) and comprised of lunch-type foods that most children report liking (37). Participants were instructed to eat until no longer hungry. From 1–1:15pm, adolescents were served a >4,000 kcal array of highly palatable snack foods (37). They were instructed to taste the foods, rate how much they liked or disliked the foods, and to eat as much as desired. Age-appropriate activities (e.g., non-stimulating magazines and books, simple table games, Nintendo DS) were available during the eating absence of hunger snack period, which lasted 15 minutes. Exact amounts consumed at the lunch meal and snack array were measured using the change in weight (to the nearest 0.1 g) of each item before and after eating, as described previously (37). Energy intakes (kcal) were calculated using the U.S. Department of Agriculture National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference (Agricultural Research Service, Beltsville, Maryland) and the manufacturers’ nutrient information obtained from food labels.

Physical Fitness

Each participant was instructed to give her best effort to walk and/or run for as long as possible in 12 minutes. Total distance traveled was assessed with a measurement wheel (Model MM34, Rolotape Corporation, Spokane, Washington). Walk/run distance is highly related to peak oxygen uptake during maximal cycle erogometry in adolescents who are obese (38).

Cortisol Response

A standardized laboratory cold-pressor stress test (CPT) paradigm, widely used in youth (39), evaluated adolescents’ cortisol reactivity. At approximately 3:00 pm, adolescents were seated in a quiet room and instructed to relax and engage in restful activities. At 4:00 pm, the cold-pressor stress test was administered. A bath of ice water was maintained at a consistent temperature of 10°C monitored by a thermometer. Each participant was instructed to keep her arm in cold water (−10°C) for as long as possible. Participants were instructed to remove their hand at any time if it became too uncomfortable for her. Salivary samples to measure cortisol were obtained with an oral swab (Sarstedt, Newton, North Carolina) placed under the tongue for 120 seconds immediately before and just after CPT and at 20, 40 and 60 minutes after the test. Intra-individual peak cortisol reactivity was assessed as the highest cortisol measurement 20–60 minutes after the test. Cortisol was measured using an enzyme immunoassay (Siemens Immulite 1000; sensitivity=60 ng/dL, intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variability=5.8–11.2%).

Statistical Methods

A planned sample size of 58/group, allowing for 30% attrition, was calculated to provide 80% power using a two-sided α level of 0.05 to detect group differences in the primary outcomes of depressive symptoms and insulin sensitivity. The power calculation was based upon results from prior studies that indicated moderate effect sizes for these outcomes in adolescents at-risk for T2D or depression (40). Analyses were conducted with SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute Incorporated, 2011). Baseline characteristics of CB and HE participants were compared with independent samples t tests and χ2 analysis. The intent-to-treat sample consisted of all participants who were randomized, regardless of whether they withdrew or were excluded from the study after randomization. The primary outcomes were depressive symptoms (CES-D total score) and insulin sensitivity (WBISI). The exploratory outcomes were alternate measures of glucose homeostasis (i.e., fasting and 2-hour insulin and glucose, HOMA-IR, IFG, and IGT), eating behavior, fitness, and cortisol stress response. A series of analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs) were conducted with change in outcome as the dependent variable and group as the independent variable. Covariates included the respective baseline outcome, baseline age, baseline pubertal status, degree of diabetes family history (≥1 first-degree relative or second-degree-relatives only), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic Black or other), group facilitator, baseline percent body fat, and change in percent body fat. Logistic regressions evaluated the group effect on odds of IFG and IGT, adjusting for baseline IFG or IGT and the same covariates.

Because depression prevention programs show larger effect sizes in adolescents with more elevated baseline depressive symptoms (40), we conducted a post hoc evaluation of baseline depressive symptom severity (mild, CES-D total score=16–20 vs. moderate, CES-D ≥21) as a moderator of group effects (40). Baseline depressive symptoms (considered continuously) and change in depressive symptoms were evaluated as predictors of changes in insulin sensitivity, eating, fitness, and cortisol. For all analyses, multiple imputation was used to handle missing data (8.6% of all data points). Following standard procedures, each data set was analyzed separately, and then, the effects were combined using the SAS MIANALYZE procedure. The missing data model included all key measures—group information, demographic characteristics, body measurements, glucose and insulin indices, eating behavior, fitness, and cortisol. Twenty imputed data sets were produced. Effect sizes for between-group differences were estimated with Cohen’s d, which can be interpreted as a small (0.2), medium (0.5), or large (0.8) effect.

Results

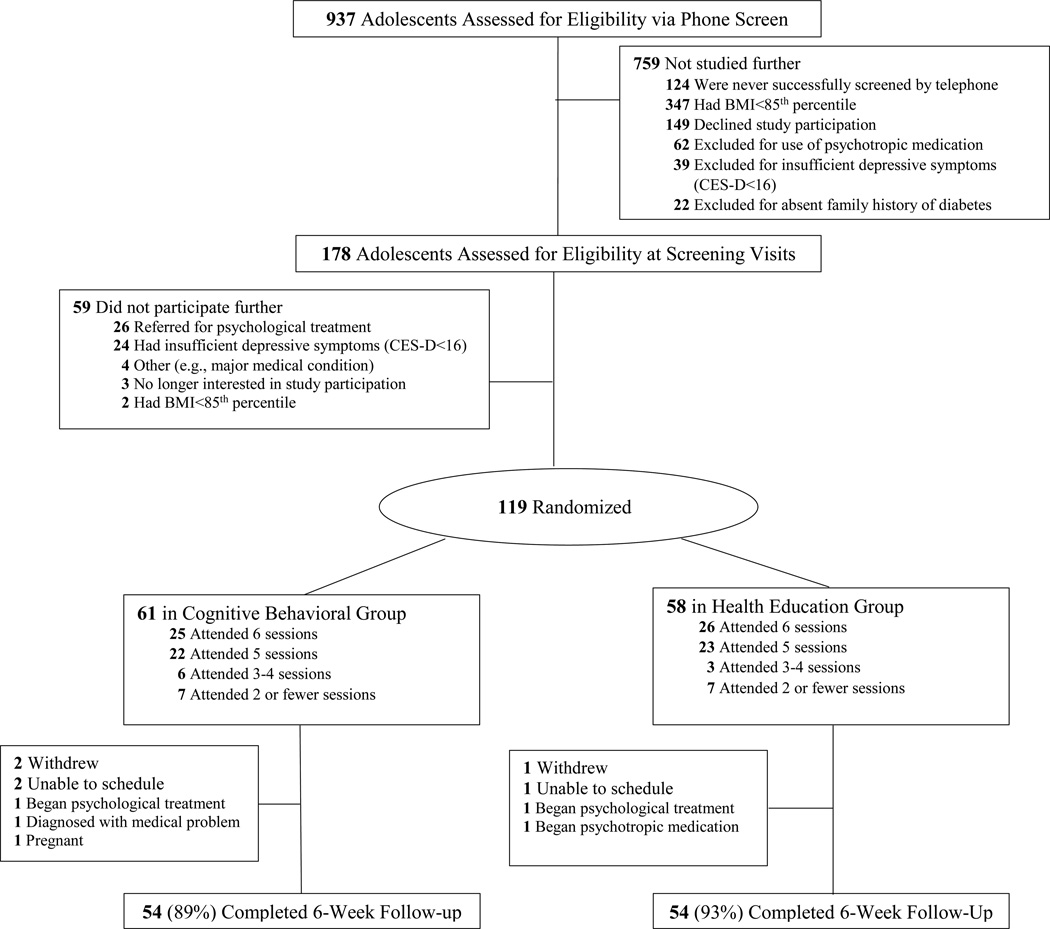

Study flow is detailed in Figure 1. Nine-hundred thirty-seven families contacted the study team. Of these, 19% of callers (n=178) had adolescents who were possibly eligible and were scheduled for laboratory screening visits. Fifty-nine girls who attended screening visits were excluded, the majority of whom either had psychological symptoms that required treatment (n=26) or who reported insufficient depressive symptoms (CES-D<16; n=24). An average of 5.3 (SD=3.2) weeks elapsed between screening and intervention initiation. One-hundred-nineteen girls were randomized to CB or HE (Table 1). Participants randomized to HE had somewhat higher, mean BMI (34.3 vs. 31.7 kg/m2, p=0.03) and BMI z (2.1 vs. 1.9, p<0.05) than participants randomized to CB; however, groups did not differ in baseline percent body fat, demographics, depressive symptoms, insulin and glucose, eating, fitness, or cortisol (p>0.10). By design, the sample was characterized by elevated depressive symptoms (CES-D total score CB 25.3 vs. HE 24.5, p=0.54). Although there are no population-based standards for metrics of insulin sensitivity and insulin resistance, both WBISI and HOMA-IR were suggestive of poor insulin sensitivity (WBISI CB 2.8 vs. HE 2.3, p=0.14) and elevated insulin resistance (HOMA-IR CB 4.9 vs. HE 5.7, p=0.14), based upon suggested clinically-relevant cut-points (insulin resistance = WBISI<5.0 and HOMA-IR>2.29) (41).

Figure 1.

Participant study flow.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of all randomized participants by cognitive-behavioral (CB) or health education (HE) group assignment

| Characteristic | CB (n=61) |

HE (n=58) |

p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | |||

| Age, years† | 15.0 (0.2) | 15.1 (0.2) | 0.81 |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | 0.94 | ||

| Black | 39 (63.9) | 35 (60.3) | |

| White | 8 (13.1) | 11 (19.0) | |

| Hispanic | 7 (11.5) | 6 (10.3) | |

| Asian | 2 (3.3) | 2 (3.4) | |

| Multiple races | 5 (8.2) | 4 (6.9) | |

| Hollingshead index of socioeconomic status‡ | 3, 1–4 | 3, 1–4 | 0.25 |

| First-degree diabetes relative, n (%) | 20 (32.8) | 27 (46.6) | 0.13 |

| Anthropometric | |||

| BMI, kg/m2† | 31.7 (0.8) | 34.3 (0.9) | 0.034 |

| BMI z score† | 1.9 (0.1) | 2.1 (0.1) | 0.047 |

| Body fat, %† | 43.4 (0.7) | 44.8 (0.8) | 0.19 |

| BMI ≥95th percentile, n (%) | 41 (67.2) | 46 (79.3) | 0.14 |

| Tanner breast stage‡ | 5 | 5 | 0.57 |

| Depressive symptoms | |||

| CES-D score† | 25.3 (0.9) | 24.5 (1.0) | 0.54 |

| CES-D score >20, n (%) | 42 (68.9) | 36 (62.1) | 0.44 |

| Glucose homeostasis | |||

| Fasting insulin, mIU/L† | 22.0 (1.6) | 26.2 (2.0) | 0.10 |

| Fasting glucose, mg/dL† | 88.6 (0.9) | 89.5 (0.9) | 0.48 |

| 2-hour insulin, mIU/L† | 115.8 (10.6) | 135.5 (13.6) | 0.25 |

| 2-hour glucose, mg/dL† | 102.8 (2.7) | 105.8 (3.0) | 0.45 |

| HOMA-IR† | 4.9 (0.4) | 5.7 (0.4) | 0.14 |

| WBISI† | 2.8 (0.2) | 2.3 (0.2) | 0.14 |

| HbA1c(%) | 5.3 (0.05) | 5.3 (0.04) | 0.93 |

| Eating, fitness, and cortisol | |||

| Lunch meal intake, kcal† | 1452 (70) | 1606 (78) | 0.14 |

| Snack intake, kcal† | 377 (20) | 382 (22) | 0.87 |

| Walk/run distance, m† | 1246 (28) | 1188 (29) | 0.19 |

| Peak cortisol reactivity, ng/dL† | 81.3 (4.5) | 83.8 (5.0) | 0.70 |

Mean (SE).

Median.

BMI=Body mass index. CES-D=Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale. HOMA-IR=Homeostatis Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance. WBISI=Whole Body Insulin Sensitivity Index. HbA1c=glycated hemoglobin.

Post-treatment assessments were conducted within a mean of 1.6 (SD=1.3) weeks after the 6-week CB or HE group finished. Median program attendance, 5 of 6 sessions, did not differ between groups (p=0.82). Median expert ratings of CB sessions for facilitator competence were 7.8 (scale of 1=poor to 10=superior) and 7.7 for fidelity (scale of 1=none to 10=perfect match for CB content). Median ratings of HE sessions were 1 for CB fidelity, confirming no key content overlap between treatment arms.

At post-treatment, 4 teens in CB and 2 in HE were not assessed because they withdrew from the study or were unable to be scheduled. An additional 3 participants in CB and 2 in HE were withdrawn by the investigators because they no longer met eligibility criteria (Figure 1). Overall attrition after randomization was, thus, low in both CB (11%) and HE (7%, p=0.82). Adolescents who completed a post-treatment follow-up (n=108) did not significantly differ from girls who were randomized, but not evaluated at post-treatment (n=11) on any variable (p>0.08).

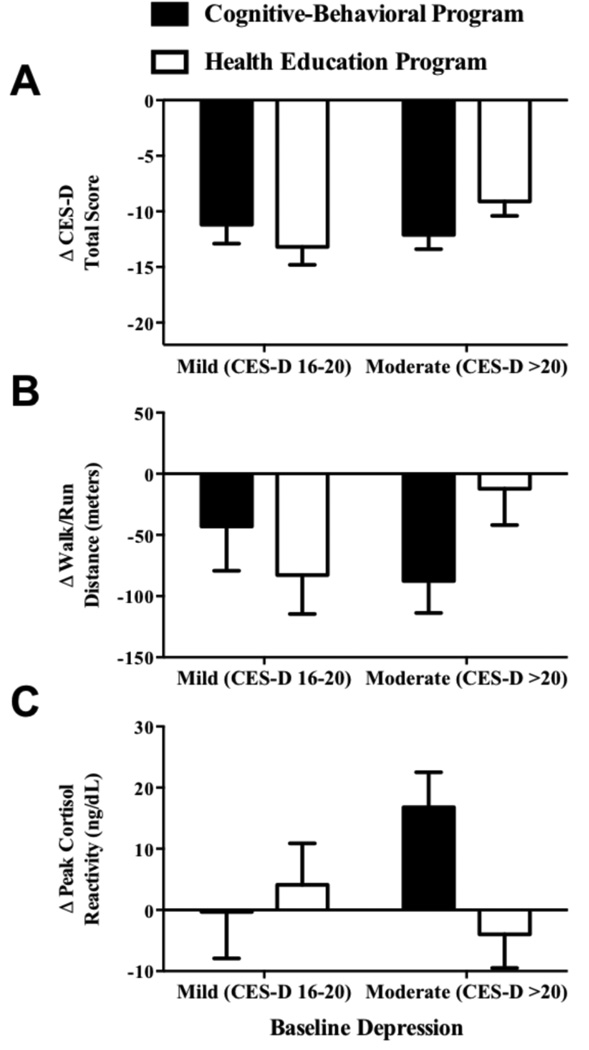

Changes in Primary Mental Health Outcome of Depressive Symptoms

Adjusting for all covariates, significant decreases from baseline to post-treatment in the primary outcome of depressive symptoms were observed in both CB and HE (p< 0.001), with no difference between groups (Cohen’s d=0.15; Table 2). In post hoc analyses, baseline depressive symptom severity moderated the treatment effect on change in depressive symptoms (p<0.05; Figure 2): Significantly greater reductions in depressive symptoms were observed for CB compared to HE among girls who had moderately elevated (vs. mild) depressive symptoms at baseline (Cohen’s d=0.38).

Table 2.

Changes in outcomes from baseline to post-treatment for cognitive-behavioral (CB) and health education (HE) groups, and comparison of changes between CB and HE

| Mean (SE)† | Time Effect | Between Group Effect† | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Δpost-baseline | p Value | ΔCB-HE (95% CI) | p Value |

| CES-D Score | ||||

| CB | −11.9 (1.0) | <0.001 | −1.2 (−3.6, 1.1) | 0.31 |

| HE | −10.7 (0.9) | <0.001 | ||

| Fasting insulin, mIU/L | ||||

| CB | 1.1 (1.5) | 0.48 | −0.2 (−3.9, 3.5) | 0.93 |

| HE | 1.3 (1.5) | 0.39 | ||

| Fasting glucose, mg/dL | ||||

| CB | 0.9 (1.3) | 0.46 | 2.3 (−0.7, 5.3) | 0.14 |

| HE | −1.3 (1.1) | 0.25 | ||

| 2-hour insulin, mIU/L | ||||

| CB | 8.4 (11.5) | 0.47 | 15.2 (−12.6, 43.0) | 0.28 |

| HE | −6.8 (10.9) | 0.53 | ||

| 2-hour glucose, mg/dL | ||||

| CB | 6.5 (3.0) | 0.03 | 6.9 (−0.7, 14.4) | 0.07 |

| HE | −0.3 (2.9) | 0.91 | ||

| HOMA-IR | ||||

| CB | 0.2 (0.4) | 0.60 | 0.01 (−0.9, 0.9) | 0.97 |

| HE | 0.2 (0.4) | 0.59 | ||

| WBISI | ||||

| CB | 0.1 (0.2) | 0.66 | −0.1 (−0.6, 0.4) | 0.63 |

| HE | 0.2 (0.2) | 0.29 | ||

| Lunch meal intake, kcal | ||||

| CB | 13.8 (69.5) | 0.84 | 19.5 (−149.5, 188.5) | 0.82 |

| HE | −5.7 (64.4) | 0.93 | ||

| Snack intake, kcal | ||||

| CB | 117.4 (26.6) | <0.001 | 55.5 (−6.9, 117.9) | 0.08 |

| HE | 61.9 (23.8) | <0.01 | ||

| Walk/run distance, meters | ||||

| CB | −73.8 (23.0) | 0.001 | −34.2 (−91.5, 23.1) | 0.24 |

| HE | −39.6 (24.1) | 0.10 | ||

| Peak cortisol reactivity, ng/dL | ||||

| CB | 11.3 (4.9) | 0.02 | 12.2 (1.0, 23.4) | 0.03 |

| HE | −0.9 (4.6) | 0.85 | ||

CES-D=Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale. WBISI=Whole Body Insulin Sensitivity Index. Peak cortisol stress reactivity=peak cortisol value 20–60 min following cold-pressor stress test.

All change effects are controlling for the baseline level of the respective outcome, baseline age, puberty, race/ethnicity, baseline percent body fat and change in percent body fat, degree of diabetes family history, and group facilitator.

Figure 2.

Interaction of group by baseline depressive symptoms (CES-D: Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale) in predicting continuous changes from baseline to post-treatment in depressive symptoms (Panel A; p<0.05), walk/run distance (Panel B; p=0.04), and peak cortisol reactivity (Panel C; p=0.03). Estimates adjusted for baseline depressive symptoms (A), walk/run distance (B), or peak cortisol reactivity (C), and baseline age, puberty, race/ethnicity, baseline percent body fat, change in percent body fat, degree of diabetes family history, and group facilitator.

In HE, 1 participant developed MDD at post-treatment, and another adolescent in HE started psychotherapy for depression during the group. In the CB group, 1 participant started anti-depressant medication during the protocol.

Changes in Primary Metabolic Outcome of Insulin Sensitivity and Exploratory Indices of Glucose Homeostasis

There was no significant change over time in the primary outcome of WBISI or in the exploratory outcomes of fasting insulin, fasting glucose, 2-hour insulin, or HOMA-IR from baseline to post-treatment across both groups (p>0.25). A slight rise in the exploratory outcome of 2-hour glucose was observed in CB participants (6.5 mg/dL, p=0.03), and this increase did not differ significantly from HE (−0.3 mg/dL, p=0.07, Cohen’s d=−0.32). In post hoc analyses, baseline depressive symptom severity did not moderate the effect of group on any insulin or glucose outcome (all p>0.36).

At post-treatment, no participants developed T2D. Table 3 displays a summary of the participants in each group who had OGTT results that were consistent with IFG or IGT. Odds of IFG or IGT at post-treatment did not differ by group (p>0.23). Relatively few adolescents had IFG or IGT at baseline or post-treatment, which is anticipated given that the manifestation of elevated blood glucose appears later than insulin resistance in the pathophysiological chain to T2D (42).

Table 3.

Impaired fasting glucose and impaired glucose tolerance at baseline and post-treatment in cognitive-behavioral (CB) and health education (HE) groups

| n (%) | 95% CI OR† |

p Value |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Post-Treatment | |||

| IFG | 0.5, 8.2 | 0.34 | ||

| CB | 4 (6.6) | 7 (11.5) | ||

| HE | 3 (5.2) | 5 (8.6) | ||

| IGT | 0.3, 135.9 | 0.23 | ||

| CB | 4 (6.6) | 4 (6.6) | ||

| HE | 4 (6.9) | 1 (1.7) | ||

IFG=impaired fasting glucose, ≥100 mg/dL. IGT=impaired glucose tolerance, 2-hour glucose ≥140 mg/dL.

Odds ratios (OR) refer to the group effect on the likelihood of IFG and IGT at post-treatment, and are controlling for baseline IFG or IGT, baseline age, puberty, race/ethnicity, baseline percent body fat and change in percent body fat, degree of diabetes family history, and group facilitator.

Association of Changes in Depression with Changes in Markers of Glucose Homeostasis

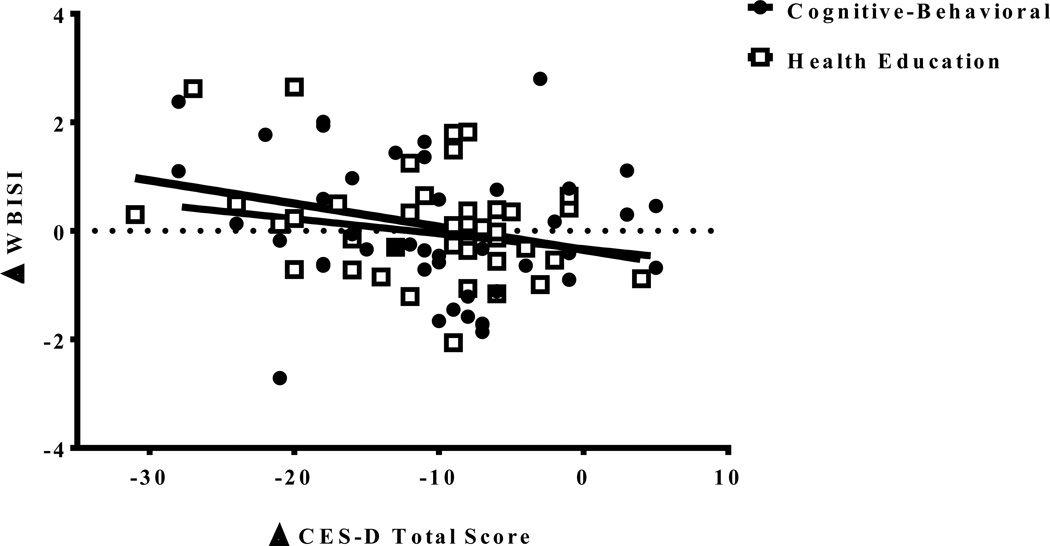

Changes in the two main study outcomes were related to each other: Reductions in depressive symptoms from baseline to post-treatment, regardless of group assignment, were related to improvements in WBISI (B=−0.04, 95% CI −0.07 to −0.01, p=0.02) (Figure 3). This effect was not moderated by group (p=0.91). Baseline to post-treatment decreases in depressive symptoms were unrelated to changes in the exploratory metabolic outcomes of fasting insulin or glucose, 2-hour insulin or glucose, or HOMA-IR (p>0.20). These non-significant associations did not differ by group assignment (p>0.64).

Figure 3.

Relationship of change from baseline to post-treatment in depressive symptoms (CES-D: Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale) and change from baseline to post-treatment in insulin sensitivity (WBISI: Whole Body Insulin Sensitivity Index) by group, accounting for baseline age, puberty, race/ethnicity, baseline percent body fat, change in percent body fat, degree of diabetes family history, and group facilitator (B=−0.04, 95% CI −0.07 to −0.01, p=0.02).

Changes in Exploratory Outcomes of Eating, Fitness, and Cortisol

There was no significant change in lunch meal intake (p>0.84), whereas increases in snack intake were observed in CB (117 kcal, p<0.001) and HE (62 kcal, p<0.01), with no between-group difference (Cohen’s d=−0.29; Table 2). In post hoc analyses, baseline depressive symptom severity was not a moderator of treatment effects on either lunch or snack intakes (p=0.59). Walk/run distance decreased from baseline to post-treatment in CB (−74 meters, p<0.001) and tended to decline in HE (−40 meters, p=0.10), with no between-group effect (Cohen’s d=−0.24). Baseline depressive symptom severity, in a post hoc analysis, moderated the group effect on change in walk/run distance (p=0.04; Figure 2B). There was no significant change in walk/run distance in girls with moderate baseline depressive symptoms in HE (−12 meters, p=0.34) and mild baseline depressive symptoms in CB (−43 meters, p = 0.23). Conversely, significant declines in walk/run distance were apparent in girls with mild baseline depressive symptoms in HE (−83 meters, p=0.01) and girls with moderate baseline depressive symptoms in CB (−88 meters, p<0.001).

There was a group effect on peak cortisol reactivity to CPT (Cohen’s d=0.31; Table 2). Girls who participated in CB displayed increases in peak cortisol reactivity (+11 ng/dL, p=0.02) from baseline to post-treatment, whereas girls in HE showed no change (−1 ng/dL, p=0.85). In post hoc analyses, baseline severity of depressive symptoms moderated the treatment effect on cortisol (p=0.03; Figure 2C). Increases in cortisol reactivity were most pronounced among girls with initially moderate depression who received CB (+17 ng/dL), compared to girls with moderate depression in HE (−4 ng/dL; Cohen’s d=0.53) and to girls with mild depression in CB (0 ng/dL; Cohen’s d=0.44) and HE (+4 ng/dL; Cohen’s d=0.33).

Discussion

In this randomized controlled trial, we sought to improve insulin sensitivity by decreasing depressive symptoms in overweight/obese adolescent girls at-risk for T2D with mild-to-moderate depressive symptoms. Girls who participated in the 6-week CB group and girls who took part in the 6-week HE group demonstrated similar decreases in depressive symptoms from baseline to post-treatment. However, in post hoc analyses, those with moderate baseline depressive symptoms exhibited greater symptom reductions after participation in CB. In all participants, insulin resistance and insulin sensitivity were stable, on average, from baseline to post-treatment in both conditions. Yet, in both the intervention and active control condition, decreases in depressive symptoms were related to improvements in insulin sensitivity from baseline to post-treatment.

There was no significant main effect for group on depressive symptoms. In past literature, CB depression prevention programs have typically led to better reductions in depressive symptoms and lower incidence of MDD, with moderate effect sizes in comparison to assessment-only or waitlist control (40). However, effects have been more tenuous when CB was compared to an active control such as a supportive-expressive group (26, 40). In the current study, we conservatively compared CB to a HE group matched for time, intensity, and facilitator expertise. While CB provided specialized, evidence-based training for teens on how to cope more effectively with negative mood states, both groups inherently offered elements of socio-emotional support by providing same-sex peers an opportunity to convene in a safe and supportive context under the supervision of a psychologist. Such factors may partly explain the observed decreases in depressive symptoms in both conditions. Average CES-D total score declined from 25 (both conditions at baseline) to a score of 13 (CB) or 14 (HE) at post-treatment. These post-treatment values are below a typical threshold for “elevated” symptoms (43), and potentially suggest clinically meaningful reductions. In post hoc analyses, we found that for girls who initially presented with moderate depressive symptoms (CES-D ≥21), participation in CB resulted in a small-to-moderate effect for significantly greater reductions in depressive symptoms compared to HE. The moderating effect of depressive symptom severity is highly consistent with the existing literature, illustrating more pronounced effects for depression prevention in adolescents with more elevated symptomatology (40).

Insulin sensitivity, as well as fasting insulin and insulin resistance, were stable from baseline to post-treatment in all participants. Non-intervention, longitudinal studies illustrate that insulin sensitivity declines more steeply and shows less recovery during adolescence among youth who are at high-risk for T2D (44). Yet, it is not possible to determine whether the stability in insulin sensitivity that was observed in the current study reflects clinically relevant, prevention of worsening of insulin action, or that the time period was too short to observe significant change. Although there was no group difference in fasting glucose, or rates of IFG or IGT, adolescents who participated in CB had marginal increases in 2-hour glucose concentrations that showed a trend (p=0.07) towards being greater than the change in the HE group. One possibility is that this finding reflects type 1 error (“false positive”), given the large number of exploratory insulin and glucose outcomes evaluated. Other studies involving psychotherapy or psychopharmacological treatment for depression in adults with T2D have not demonstrated worsening glycemia, and, indeed, some investigations have demonstrated glycemic improvements (17). Longer-term follow-up is needed to elucidate to what extent statistically significant and clinically meaningful changes in glucose and insulin unfold over time in developing adolescents at-risk for T2D who receive CB or HE.

Decreases in depressive symptoms were related to improvements in insulin sensitivity, even when accounting for baseline body fat, changes in body fat, and other potential confounds. Every 1-unit decrease in CES-D total score was associated with a 0.04-unit improvement in WBISI. Although relatively small, the magnitude of this association approximates the effect of intensive lifestyle intervention on 6-month WBISI change in obese adolescents at-risk for T2D (45). Even though a depression-insulin sensitivity relationship is consistent with the theoretical basis of the current study and parallels past literature (14, 46), the correlational nature of this association among all study participants precludes any causal inferences about whether reductions in depressive symptoms caused improvements in insulin sensitivity.

Adolescents in CB, but not HE, showed an increased peak cortisol response to a late-afternoon laboratory CPT at post-treatment. Greater depressive symptoms have been related to a more blunted physiological baseline cortisol reaction to a CPT (21). Prior studies have also found that youth who display a blunted cortisol response to a stressor are more likely to experience recurrence of depressive symptoms than those who react physiologically to an acute stressor (47). The symptomatology of depression in overweight and obese individuals is often characterized by a so-called “atypical” profile, including psychomotor retardation, fatigue, excessive appetite and overeating, and hyposomnia. This profile has been associated with less or blunted cortisol reactivity as compared to individuals with “typical” depression or controls (48). The ability to mobilize resources to react to acute stressors is likely a positive health benefit for this particular group. To what extent this mobilization of stress response has implications, in the longer-term, for insulin sensitivity and T2D risk merits investigation.

Behavioral changes in eating and physical fitness were measured in the sample, with no significant group effect. Adolescents had similar lunch meal intakes from baseline to post-treatment, but they displayed significant increases in snack intake in the absence of hunger. Walk/run distance decreased from baseline to post-treatment as well. These exploratory findings may reflect normative population trends in eating in the absence of hunger and physical fitness in overweight/obese girls during adolescence. Alternatively, it is possible that increases in snack intake and decreases in walk/run distance were partially due to test-retest effects of repeated measurements, spaced relatively close together in time. Alternative measurements of these constructs, for instance, via ecological momentary assessment surveys of eating and activity, accelerometers, or even maximal exercise testing such as with cycle ergometry, may shed more light on the nature and meaning of these changes. Also, a longer follow-up interval would permit the determination of whether CB may have a longer-acting effect on eating and fitness over time, as opposed to immediately after treatment.

A strength of this study is the focus on prevention of T2D during adolescence, through intervening with a novel, targeted risk factor for insulin resistance—depressive symptoms. We collected multiple anthropometric, psychological, physiological, and behavioral measurements using well-validated and objective assessment tools. The study had excellent program adherence and follow-up retention. Limitations of the study include the utilization of OGTT testing to assess insulin sensitivity as opposed to clamp-derived measures. The approach employed, however, is more feasible in larger-scale samples and clinical trials and is highly related to gold-standard clamp-derived measures in overweight/obese adolescents (34). We studied a sample characterized by elevated depressive symptoms, but there was heterogeneity in mild to moderate symptomatology; no participants were clinically depressed. Further, we did not evaluate depressive symptoms in the ~5 weeks that elapsed between the baseline screening and initiation of the intervention, precluding determination of possible changes in depressive symptoms during that period. Likewise, adolescents were determined to be at-risk for T2D based upon overweight or obesity and a first- or second-degree family history of T2D, criteria similar to previous T2D prevention trials. Although baseline WBISI and HOMA-IR were suggestive of insulin resistance, our findings may or may not be applicable to youth at more heightened risk (e.g. prediabetes). Furthermore, while most participants were non-Hispanic Black, there was limited representation of other racial/ethnic minority groups at disproportionate risk for T2D including adolescents of Hispanic and American Indian descent. Taken together, such sample characteristics may limit the generalizability of the findings.

We elected to evaluate the impact of a CB group on depression and insulin sensitivity in comparison to a didactic, active control comparison condition matched for time, intensity, and leader competence. This design has the advantage of attributing any observed effects to CB, as opposed to time and attention, although didactic approaches typically have limited effects on sustained behavior change. We did not have a third, assessment-only arm, which prohibits information about the relative effects of CB or HE to no treatment at all in adolescent girls at-risk for T2D. It cannot be determined if the observed decreases in depressive symptoms in CB and HE were caused by program participation or reflect regression to the mean. We utilized an unmodified, stand-alone CB depression program to intentionally determine the unique impact of targeting decreases in depressive symptoms on insulin resistance. Future iterations possibly could be more effective if adapted to address behavioral issues specific to T2D risk. In adults with depression and T2D, for instance, psychotherapy interventions that explicitly address the impact of depression on treatment adherence hold particular promise (49). The short-term, post-treatment follow-up interval also is a methodological limitation. The persistence, desistance, or emergence of group effects on outcomes during a longer window should be determined. Having only two measurement occasions also prohibited examination of mediational analyses to evaluate proposed behavioral and physiological mechanisms of depression change and insulin sensitivity change. The relatively small sample size also limited mediation, and introduces the possibility of a type II error for all outcomes.

The immediate post-treatment findings are clinically relevant, as they suggest that relatively brief CB and HE group participation are associated with declines in depressive symptoms, and that such declines are related to improvements in insulin sensitivity. Adolescent girls with more elevated initial depressive symptoms who received CB had greater reductions in depressive symptoms at post-treatment in comparison to HE. In addition, CB participants had an enhanced cortisol response to a laboratory stressor relative to HE; which was particularly pronounced among those girls who started with more elevated depressive symptoms. Taken together, the findings provide support for the possibility that intervening to decrease elevated depressive symptoms in overweight/obese adolescent girls at-risk for T2D may be beneficial for mood and potentially metabolic outcomes. To what extent CB or HE provide sustained benefits in depression, insulin metabolism, or stress response will be determined with longer-term follow-up.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by K99HD069516 and R00HD069516 (L.B.S.) from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), National Institutes of Health (NIH) Intramural Research Program Grant 1ZIAHD000641 (J.A.Y.) from NICHD with supplemental funding from the NIH Bench to Bedside Program (L.B.S., M.T., J.A.Y.), Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research (J.A.Y.), and the NIH Office of Disease Prevention (J.A.Y.). C.K.P. was supported by a training award from the NIH Office of the Director. S.A.A. was supported by the NIH Medical Research Scholars Program, a public-private partnership supported jointly by the NIH and generous contributions to the Foundation for the NIH from Pfizer Inc., The Doris Duke Charitable Foundation, The Newport Foundation, The American Association for Dental Research, The Howard Hughes Medical Institute, and the Colgate Palmolive Company, as well as other private donors. The authors acknowledge the assistance of Heather Shaw, Ph.D., Oregon Research Institute for her help in rating intervention sessions for fidelity and leader competence.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors having nothing to disclose.

Clinical trial reg. no: NCT01425905, clinicaltrials.gov

References

- 1.Forouhi NG, Wareham NJ. Epidemiology of diabetes. Medicine (Abingdon) 2014;42:698–702. doi: 10.1016/j.mpmed.2014.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gregg EW, Zhuo X, Cheng YJ, et al. Trends in lifetime risk and years of life lost due to diabetes in the USA, 1985–2011: a modelling study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinology. 2014;2:867–874. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(14)70161-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dabelea D, Mayer-Davis EJ, Saydah S, et al. Prevalence of type 1 and type 2 diabetes among children and adolescents from 2001 to 2009. JAMA. 2014;311:1778–1786. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.3201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ducat L, Philipson LH, Anderson BJ. The mental health comorbidities of diabetes. JAMA. 2014;312:691–692. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.8040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, Clouse RE, Lustman PJ. The prevalence of comorbid depression in adults with diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:1069–1078. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.6.1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hood KK, Beavers DP, Yi-Frazier J, et al. Psychosocial burden and glycemic control during the first 6 years of diabetes: results from the SEARCH for Diabetes in Youth study. J Adolesc Health. 2014;55:498–504. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Semenkovich K, Brown ME, Svrakic DM, Lustman PJ. Depression in type 2 diabetes mellitus: prevalence, impact, and treatment. Drugs. 2015;75:577–587. doi: 10.1007/s40265-015-0347-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu M, Zhang X, Lu F, Fang L. Depression and risk for diabetes: a meta-analysis. Can J Diabetes. 2015;39:266–272. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjd.2014.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morrison JA, Glueck CJ, Horn PS, Wang P. Childhood predictors of adult type 2 diabetes at 9- and 26-year follow-ups. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164:53–60. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hannon TS, Li Z, Tu W, et al. Depressive symptoms are associated with fasting insulin resistance in obese youth. Pediatr Obes. 2014;9:e103–e107. doi: 10.1111/ijpo.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hannon TS, Rofey DL, Lee S, Arslanian SA. Depressive symptoms and metabolic markers of risk for type 2 diabetes in obese adolescents. Pediatr Diabetes. 2013;14:497–503. doi: 10.1111/pedi.12035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shomaker LB, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Young-Hyman D, et al. Psychological symptoms and insulin sensitivity in adolescents. Pediatr Diabetes. 2010;11:417–423. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2009.00606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jaser SS, Holl MG, Jefferson V, Grey M. Correlates of depressive symptoms in urban youth at risk for type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Sch Health. 2009;79:286–292. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2009.00411.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shomaker LB, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Stern EA, et al. Longitudinal study of depressive symptoms and progression of insulin resistance in youth at risk for adult obesity. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:2458–2463. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Winokur A, Maislin G, Phillips JL, Amsterdam JD. Insulin resistance after oral glucose tolerance testing in patients with major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1988;145:325–330. doi: 10.1176/ajp.145.3.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okamura F, Tashiro A, Utumi A, et al. Insulin resistance in patients with depression and its changes during the clinical course of depression: minimal model analysis. Metabolism. 2000;49:1255–1260. doi: 10.1053/meta.2000.9515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baumeister H, Hutter N, Bengel J. Psychological and pharmacological interventions for depression in patients with diabetes mellitus: an abridged Cochrane review. Diabet Med. 2014;31:773–786. doi: 10.1111/dme.12452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stice E, Presnell K, Spangler D. Risk factors for binge eating onset in adolescent girls: a 2-year prospective investigation. Health Psychol. 2002;21:131–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shomaker LB, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Zocca JM, et al. Depressive symptoms and cardiorespiratory fitness in obese adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2012;50:87–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jerstad SJ, Boutelle KN, Ness KK, Stice E. Prospective reciprocal relations between physical activity and depression in female adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2010;78:268–272. doi: 10.1037/a0018793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keenan K, Hipwell A, Babinski D, et al. Examining the developmental interface of cortisol and depression symptoms in young adolescent girls. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;38:2291–2299. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fisher JO, Cai G, Jaramillo SJ, et al. Heritability of hyperphagic eating behavior and appetite-related hormones among Hispanic children. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15:1484–1495. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dwyer T, Magnussen CG, Schmidt MD, et al. Decline in physical fitness from childhood to adulthood associated with increased obesity and insulin resistance in adults. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:683–687. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reinehr T, Andler W. Cortisol and its relation to insulin resistance before and after weight loss in obese children. Horm Res. 2004;62:107–112. doi: 10.1159/000079841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stice E, Rohde P, Seeley JR, Gau JM. Brief cognitive-behavioral depression prevention program outperforms two alternative interventions: a randomized efficacy trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76:595–606. doi: 10.1037/a0012645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stice E, Rohde P, Gau JM, Wade E. Efficacy trial of a brief cognitive-behavioral depression prevention program for high-risk adolescents: effects at 1- and 2-year follow-up. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2010;78:856–867. doi: 10.1037/a0020544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bravender T. Health, Education, and Youth in Durham: HEY-Durham Curricular Guide. 2nd. Durham, NC: Duke University; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tanofsky-Kraff M, Shomaker LB, Wilfley DE, et al. Targeted prevention of excess weight gain and eating disorders in high-risk adolescent girls: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;100:1010–1018. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.092536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tanofsky-Kraff M, Wilfley DE, Young JF, et al. A pilot study of interpersonal psychotherapy for preventing excess weight gain in adolescent girls at-risk for obesity. Int J Eat Disord. 2010;43:701–706. doi: 10.1002/eat.20773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Variations in pattern of pubertal changes in girls. Arch Dis Child. 1969;44:291–303. doi: 10.1136/adc.44.235.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, et al. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nolen-Hoeksema S, Stice E, Wade E, Bohon C. Reciprocal relations between rumination and bulimic, substance abuse, and depressive symptoms in female adolescents. J Abnorm Psychol. 2007;116:198–207. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.1.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yeckel CW, Weiss R, Dziura J, et al. Validation of insulin sensitivity indices from oral glucose tolerance test parameters in obese children and adolescents. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:1096–1101. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yeckel CW, Weiss R, Dziura J, et al. Validation of insulin sensitivity indices from oral glucose tolerance test parameters in obese children and adolescents. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:1096–1101. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, et al. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia. 1985;28:412–419. doi: 10.1007/BF00280883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shomaker LB, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Zocca JM, et al. Eating in the absence of hunger in adolescents: intake after a large-array meal compared with that after a standardized meal. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92:697–703. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.29812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Drinkard B, McDuffie J, McCann S, et al. Relationships between walk/run performance and cardiorespiratory fitness in adolescents who are overweight. Phys Ther. 2001;81:1889–1896. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.von Baeyer CL, Piira T, Chambers CT, Trapanotto M, Zeltzer LK. Guidelines for the cold pressor task as an experimental pain stimulus for use with children. J Pain. 2005;6:218–227. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2005.01.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stice E, Shaw H, Bohon C, Marti CN, Rohde P. A meta-analytic review of depression prevention programs for children and adolescents: factors that predict magnitude of intervention effects. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77:486–503. doi: 10.1037/a0015168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Radikova Z, Koska J, Huckova M, et al. Insulin sensitivity indices: a proposal of cut-off points for simple identification of insulin-resistant subjects. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2006;114:249–256. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-924233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Libman IM, Barinas-Mitchell E, Bartucci A, et al. Fasting and 2-hour plasma glucose and insulin: relationship with risk factors for cardiovascular disease in overweight nondiabetic children. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:2674–2676. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stockings E, Degenhardt L, Lee YY, et al. Symptom screening scales for detecting major depressive disorder in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis of reliability, validity and diagnostic utility. J Affect Disord. 2015;174:447–463. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goran MI, Shaibi GQ, Weigensberg MJ, Davis JN, Cruz ML. Deterioration of insulin sensitivity and beta-cell function in overweight Hispanic children during pubertal transition: a longitudinal assessment. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2006;1:139–145. doi: 10.1080/17477160600780423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Savoye M, Caprio S, Dziura J, et al. Reversal of early abnormalities in glucose metabolism in obese youth: results of an intensive lifestyle randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:317–324. doi: 10.2337/dc13-1571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Holt RI, de Groot M, Golden SH. Diabetes and depression. Curr Diab Rep. 2014;14:491. doi: 10.1007/s11892-014-0491-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Calhoun CD, Franklin JC, Adelman CB, et al. Biological and cognitive responses to an in vivo interpersonal stressor: Longitudinal associations with adolescent depression. Int J Cogn Ther. 2012;5:283–299. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lamers F, Vogelzangs N, Merikangas KR, et al. Evidence for a differential role of HPA-axis function, inflammation and metabolic syndrome in melancholic versus atypical depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18:692–699. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Safren SA, Gonzalez JS, Wexler DJ, et al. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioral therapy for adherence and depression (CBT-AD) in patients with uncontrolled type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:625–633. doi: 10.2337/dc13-0816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]