Abstract

Aims

Data from the Patients and Families Psychological Response to the Home Automated External Defibrillator Trial were used to examine the relationship between biopsychosocial variables and patients’ coping strategies post-myocardial infarction.

Design

Analysis of secondary data derived from a longitudinal observational study.

Methods

A total of 460 patient-spouse pairs were recruited in January 2003 to October 2005. Hierarchical linear regression analysis examined biological/demographic, psychological, and social variables regarding patients’ coping scores using the Family Crisis Oriented Personal Evaluation Scale.

Results

Lower social support and social support satisfaction predicted lower total coping scores. Being younger, male gender, and time since the myocardial infarction predicted lower positive coping strategy use. Higher anxiety and lower social support were related to fewer positive coping methods. Lower educational levels were related to increased use of negative coping strategies. Reduced social support predicted lower total coping scores and positive coping strategy use, and greater passive coping style use. Social support from a broad network assisted with better coping; those living alone may need additional support.

Conclusion

Social support and coping strategies should be taken into consideration for patients who have experienced a cardiac event.

Keywords: biopsychosocial, coping strategies, myocardial infarction, nursing, social support

INTRODUCTION

Coping is defined as constantly changing cognitive and behavioural efforts to deal with external and/or internal demands that exceed resources.1,2 Individuals use various coping strategies when confronting sudden life-threatening situations, such as myocardial infarction (MI).3 MI influences the individual's biopsychosocial wellbeing and imposes limitations on his/her everyday functioning and life in general. After an acute MI, there is a higher risk for recurrent cardiac events.3-5 When they return home, most of patients experience some or all of the following feelings, including existential dread, guilt, denial, and loss of their former way of life.6 They have been informed about the need for life-long medication and lifestyle changes. Therefore, coping strategies are used to modify physiological and psychological stress reactions.2,6 In addition, coping abilities are required to manage subsequent events.7 Effective coping should be viewed in the context of individual circumstances and personal experiences.1,7,8 Accordingly, healthcare providers need to understand that the ability to cope is affected by various factors.

The biopsychosocial model suggests that biological, psychological, and social factors are all interlinked. 9 This model provides the basis for understanding the holistic approach to patient care and disease determinants.9 The biopsychosocial model has been used extensively in the understanding of risk for the development and progression of coronary heart disease.10,11 According to previous studies2,7,12 biological, psychological, and social factors are related to coping strategy use.

Biological variables used by female patients included a higher number of evasive,3 problem-focused, emotional avoidance,4 and spiritually-based coping strategies,5 while men were less likely to wait and see or attempt to relax.6 No association existed between age and coping strategies used.5,7,8

Emotion-focused coping strategies during the cardiac event significantly predicted disease severity (i.e., lower-left ventricular ejection fraction) in patients with acute coronary syndrome.9 Negative emotional coping decreased with time for six months following MI.8 A negative relationship between coping strategy use and psychological distress was reported. Anxious or depressed patients used fewer cognitive, social, emotional, spiritual, and physical coping resources,10 significantly fewer confrontational and optimistic coping strategies,11 and tended to use negative coping methods more frequently.12,13

Social factors are interrelated with coping and psychological distress. Higher social support levels and lower use of negative coping were associated with fewer depressive symptoms.14 Greater use of religiosity in coping reduced anxiety.15 Spiritual conviction and prayer supported MI patients’ coping.16 Additionally, lower educational levels were associated with a higher number of spiritual coping strategies; and single participants used a higher number of spiritual activities and religious avoidance coping styles compared to married individuals.5

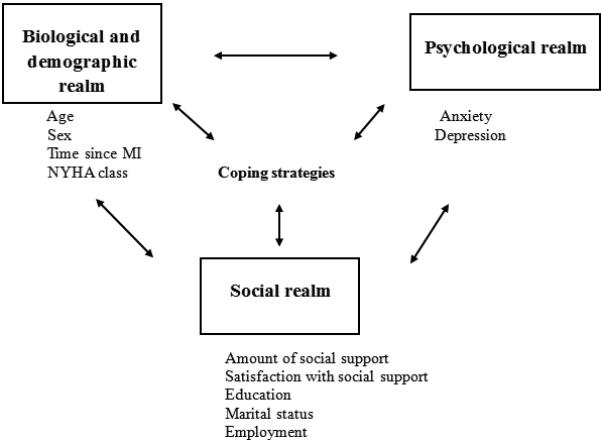

Examining coping strategies in a manner that encompasses biopsychosocial factors is both necessary and important.12,13,17 However, these three domains of the biopsychosocial model have been studied individually. Therefore, this study examined the contributions of the biopsychosocial model for post-MI coping strategies. Figure 1 depicts the biopsychosocial model for post-MI coping: age, sex, NYHA class, and time since last MI entail the biological realm and anxiety and depression in the psychological realm affect coping strategies. Social support, education, marital status, and employment in the social realm interact with biological and psychological variables to influence post-MI coping.

Figure 1.

Biopsychosocial model for coping strategy use in post-myocardial infarction patients.

In this study, the research questions were:

-

(a)

Do biopsychosocial variables predict total coping scores in post-MI patients?

-

(b)

Do biopsychosocial variables predict positive or negative coping strategy use in the five subdomains of the coping instrument?

METHODS

Design

Secondary analysis of data from the Patients’ and Families’ Psychosocial Responses in the Home Automated External Defibrillator Trial (PR-HAT) was performed to answer the research questions. The HAT was designed to test whether an automated external defibrillator(AED) in the home of stable post-MI patients improved survival.

Sample

The PR-HAT included 460 community-dwelling patients who had experienced MI and their spouses or companions. 30 sites in Australia (12), Canada (5), New Zealand (2), and the United States (11) were invited to participate in PR-HAT.

Data collection

The PR-HAT was a longitudinal observational study involving participants in the Home Automated External Defibrillator Trial (HAT: Registry: NCT00047411).18 The HAT study recruited patient-spouse pairs from January 2003 to October 2005. The PR-HAT began recruitment in October 2003, simultaneously with HAT. It compared the effects of two interventions (cardiopulmonary resuscitation training [CPR] and CPR plus automated external defibrillation) on psychosocial factors over two years.19 Psychosocial factors – anxiety, depression, coping, and social support – were measured over two years. The patients completed all scales.

Instruments

The measurement tools used in this study have been reported with good to excellent reliability and construct and concurrent validity in previous studies.20,21

The Family Crisis Oriented Personal Evaluation Scale (FCOPES) is a 30-item instrument, which is used to identify problem-solving and behavioural strategies used by families in crisis or problem situations.22 The measure uses a 5-point Likert Scale with responses ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” There are five subscales: acquiring social support, reframing, seeking spiritual support, mobilizing family to acquire and accept help, and passive appraisal. Table 1 presents the FCOPES subscale descriptions. Total FCOPES scores range from 30 to 150; higher scores indicate better coping during a stressful situation.22

Table 1.

| Subscales | Definition |

|---|---|

| Acquiring social support Items 1, 2, 5, 8, 10, 16, 20, 25, and 29 |

A family's ability to actively engage in support acquisition from available resources such as friends and neighbours |

| Refraining Items 3, 7, 11, 13, 15,19, 22, and 24 |

A family's capacity to redefine stressful events and render them more manageable |

| Seeking spiritual support Items 14, 23, 2,7, and 30 |

A family's ability to seek spiritual advice |

| Mobilizing family to acquire and accept help Items 4, 6, 9, and 21 |

A family's ability to acquire community resources |

| Passive appraisal Items 12, 17, 26, and 28 |

A family's ability to minimize reactivity to problematic issues |

FCOPES: Family Crisis Oriented Personal Evaluation Scale

The state section of the State/Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) was used to assess anxiety.23 The STAI consists of two anxiety domains: state, which measures current anxiety levels, and trait. As a self-administered instrument, STAI consists of 20 items. Based on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from not at all (scored 0) to very much so (scored 4), respondents are asked to rate how anxious they are at the moment or have been. The total scores range from 20 to 80 with higher scores indicating greater anxiety.

The Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI-II)24 was used to measure depressive symptoms during the preceding fortnight. The BDI-II is the most commonly used tool to measure cardiac patients’ depression symptoms.25–27 The BDI-II asks respondents about how they have been feeling throughout the past 2 weeks. Based on 21 items with a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 to 3 in each question, the total scores can be between 0 and 63 with higher scores indicating higher levels of depression. 24

The Social Support Questionnaire-628 was used to examine social support; the scale assesses perceptions in relation to two aspects of social support: amount of social support received (individuals perceived as available to provide social support) and degree of satisfaction with social support. Given six social support scenarios, respondents are asked to list the people who would provide the particular type of support and to rate how satisfied they are with those people on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (very dissatisfied) to 6 (very satisfied). Higher scores on the SSQ-6 indicate more perceived availability of people providing social support and higher satisfaction from the social support.28

The reliability of the FCOPES was tested in the present sample using Cronbach's alpha (α = .851); for the five subscales values were: acquiring social support (α = .821), reframing (α = .724), seeking spiritual support (α = .915), mobilizing (α = .720), and passive appraisal (α = .620). Reliability has been previously established for the state section of the STAI29 and the BDI-II.30,31,32

Ethical considerations

The study conformed to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was obtained from the institutional review board to which the primary investigator was affiliated (Assurance number: M1174; IRB protocol number: 0603903). The study used baseline biopsychosocial data from the PR-HAT trial, the details of which have been described previously.21

Data analysis

Frequencies and means were calculated to provide descriptive statistics. Chi-square tests examined differences in categorical biopsychosocial factors between groups. Independent samples t-tests compared mean differences in FCOPES total and subscale scores between men and women; NYHA classes I (no symptoms) and II, III, and IV (symptoms); married and unmarried participants; employed and unemployed participants; and participants who had and had not graduated from secondary school. Pearson's correlation coefficients were calculated to examine relationships between continuous factors (age, time since last MI, anxiety, depression, and social support) and the FCOPES total and subscale scores.

Hierarchical linear regression analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 21.0 for Windows (IBM Inc., Armonk, NY, United States) to determine the independent contributions of the three realms of the biopsychosocial model. Based on this, the model initially included the following biological and demographic factors: age, sex, NYHA class, and time since last MI. In the second model, the psychological factors of anxiety and depression were added to the first model. In the third model, the social factors of social support, education, marital status, and employment were added to the second model. This strategy facilitated the examination of the significance of the original and additional variables’ contributions, and changes in significant predictors as variables were added. Sets of analyses were performed with the overall coping (total FCOPES score) and FCOPES subscale scores as outcome variables.

RESULTS

Participant characteristics

Data for 460 patients were analysed. Table 2 outlines the patients’ demographic characteristics. Most patients were married and had mild heart failure (97.2%; NYHA class I or II).

Table 2.

Description of participants' demographic and biopsychosocial characteristics and FCOPES† total and subscale scores (N = 460)

| Characteristics | n (%) | M (SD) | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 61.09 (9.69) | 33.1–84.3 | |

| Sex | |||

| Men | 392 (85.2) | ||

| Women | 68 (14.8) | ||

| NYHA‡ class | |||

| I | 352 (76.5) | ||

| II | 95 (20.7) | ||

| III | 12 (2.6) | ||

| IV | 1 (0.2) | ||

| Time since last MI§ (months) | 44.67 (60.88) | 0–340 | |

| State anxiety | 31.68 (9.79) | 20–71 | |

| Depression | 8.28 (6.96) | 0–41 | |

| Amount of social support received | 18.69 (13.34) | 0–54 | |

| Satisfaction with social support | 33.10 (4.37) | 6–36 | |

| Secondary school completed(yes) | 344 (74.8) | ||

| Married(yes) | 421 (91.5) | ||

| Employed(yes) | 254 (55.2) | ||

| FCOPES† | |||

| Total | 95.09 (16.25) | 55–150 | |

| Acquiring social support | 27.42 (8.12) | 9–71 | |

| Refraining | 32.17 (4.60) | 11–40 | |

| Seeking spiritual support | 10.85 (5.05) | 3–20 | |

| Mobilizing | 12.79 (3.76) | 4–20 | |

| Passive appraisal | 8.49 (3.22) | 4–20 |

FCOPES: Family Crisis Oriented Personal Evaluation Scale

NYHA: New York Health Association

MI: myocardial infarction

Relationships between biological, psychological, and social factors and coping strategies

Sex, age, time since last MI, anxiety, depression, and social support were significantly associated with the FCOPES total and subscale scores (Tables 3 and 4). Of the biological variables, age was associated with seeking spiritual support: older patients used spiritual coping strategies more frequently. For the categorical biological variables, men and women used different coping strategies. Men's total coping scores were significantly lower (t (382) = 2.76, P = .006); they used social support acquisition (t (453) = 3.01, P = .003), seeking spiritual support (t (452) = 2.28, P = .023), and mobilizing (t (454) = 3.19, P = .002) coping strategies less frequently. Time since last MI was significantly associated with coping strategy use. As the time since the MI increased, their total, social support acquisition, and mobilizing coping strategies usage decreased.

Table 3.

Average FCOPES† total and subscale scores in relation to categorical biopsychosocial variables

| Variables | Total M (SD) | Acquiring M (SD) | Refraining M (SD) | Seeking M (SD) | Mobilizing M (SD) | Passive M (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||||

| Men(n = 392) | 94.16** (16.16) | 26.95** (7.75) | 32.23 (4.30) | 10.62* (5.02) | 12.56** (3.76) | 8.55 (3.25) |

| Women(n = 68) | 100.64 (16.41) | 30.15 (9.59) | 31.83 (6.12) | 12.15 (5.10) | 14.13 (3.55) | 8.15 (3.07) |

| NYHA‡ class | ||||||

| No symptoms(n = 352) | 94.78 (15.94) | 27.48 (8.28) | 32.23 (4.41) | 10.69 (5.09) | 12.69 (3.74) | 8.29 (3.10) |

| Symptoms (n = 108) | 96.18 (17.39) | 27.24 (7.60) | 31.97 (5.19) | 11.35 (4.94) | 13.12 (3.84) | 9.16* (3.53) |

| Secondary school Completed | ||||||

| Yes(n =116) | 94.66 (16.16) | 27.40 (8.13) | 32.08 (4.63) | 10.98 (5.03) | 12.54* (3.67) | 8.25 (3.06) |

| No (n = 344) | 96.56 (16.57) | 27.47 (8.10) | 32.54 (4.51) | 10.45 (5.13) | 13.60 (3.95) | 9.21** (3.61) |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married (n = 421) | 94.92 (16.53) | 27.28 (8.27) | 32.21 (4.66) | 10.92 (5.06) | 12.75 (3.78) | 8.41 (3.27) |

| Unmarried (n = 39) | 97.14 (12.45) | 28.97 (6.11) | 31.78 (3.92) | 10.03 (5.04) | 13.21 (3.61) | 9.34* (2.54) |

| Employment | ||||||

| Employed (n = 254) | 93.47* (15.16) | 26.90 (8.22) | 32.28 (4.25) | 10.48 (5.05) | 12.39* (3.70) | 8.30 (2.96) |

| Unemployed (n = 206) | 97.24 (17.41) | 28.05 (7.97) | 32.04 (5.01) | 11.30 (5.03) | 13.28 (3.79) | 8.73 (3.52) |

P < .05

P < .01

FCOPES: Family Crisis Oriented Personal Evaluation Scale

NYHA: New York Health Association

Table 4.

Correlations between FCOPES† total and subscale scores and continuous biopsychosocial variables

| Variables | Total r | Acquiring r | Refraining r | Seeking r | Mobilizing r | Passive r |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | .097 | .059 | .091 | .171** | −.033 | −.016 |

| Time since MI‡ | −.121* | −.126** | .028 | −.016 | −.098* | −.056 |

| Anxiety | −.059 | −.049 | −.279** | −.073 | .056 | .246** |

| Depression | −.047 | −.095* | −.263** | −.058 | .019 | .258** |

| Amount of social support received | .158** | .249* | .078 | .109* | .086 | −.187** |

| Satisfaction with social support | .205** | .172** | .304** | .140** | .083 | −.198** |

P < .05

P < .01

FCOPES: Family Crisis Oriented Personal Evaluation Scale

MI: myocardial infarction

The psychological variables, anxiety and depression, were significantly associated with three coping subscales. Patients who were more anxious and depressed used reframing coping strategies less frequently. Patients who were more anxious and depressed also used passive coping strategies more frequently.

Both types of social support factors were related to coping strategy use. Satisfaction with social support was significantly associated with most coping strategies. Higher amounts of social support and greater satisfaction with social support were associated with higher total coping scores, increased acquisition of social support, reframing, and seeking spiritual support coping strategy use as well as reduced passive coping strategy use.

Model development procedure and findings

The first model examined the influence of biological and demographic variables on the total FCOPES and subscale scores. Men and younger patients used fewer positive coping strategies, including acquiring social support, reframing, seeking spiritual support, and mobilizing. Patients with a higher NYHA class used a higher number of passive coping strategies.

What is the influence of biopsychosocial variables on the total FCOPES score?

In the final model of the influence of biological, demographic, psychological, and social variables on the total FCOPES score, social and psychological variables were added to the previous model, which included biological and demographic variables, to examine the contribution of social factors to total coping scores (see Table 5). The final model was superior to the previous model (P = .004), which included biological and psychological variables, and predicted the total FCOPES scores [F (11,340) = 3.46, P < .001]. When all biological, demographic, and psychosocial variables were included in the model, only social support significantly predicted the total FCOPES scores. The lower the amount of social support (P = .024) received and the less satisfied patients were with their social support (P = .010), the lower their total FCOPES scores.

Table 5.

Unstandardized regression coefficients from the hierarchical regression analysis predicting FCOPES† total and subscale scores: final model, biological, demographic, psychological, and social predictors

| Predictors | Total | Acquiring | Refraining | Spiritual | Mobilizing | Passive |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biological and demographic variables | ||||||

| Age (years) | .141 | .059 | .022 | .098** | −.018 | .004 |

| Women | 4.186 | 2.354* | −.777 | 1.512* | 1.145* | −.565 |

| NYHA‡ II, III, or IV | 2.044 | .208 | .321 | .542 | .315 | .295 |

| Time since MI§ (months) | −.029 | −.014* | .001 | −.003 | −.005 | −.004 |

| Psychological variables | ||||||

| Anxiety | −.038 | .057 | −.076* | .000 | .033 | .035 |

| Depression | −.006 | −.121 | −.063 | −.026 | −.020 | .053 |

| Social variables | ||||||

| Amount of social support | .153* | .130** | −.003 | .028 | .020 | −.025* |

| Satisfaction with social support | .573* | .181 | .268** | .127* | .062 | −.092* |

| Secondary school completed | −.582 | .201 | −.221 | .632 | −.916* | −.865* |

| Married | 2.877 | 2.294 | −.211 | −1.400 | .438 | 1.018 |

| Employed | −2.601 | −1.349 | .527 | −.010 | −1.029* | −.252 |

| R 2 | .101** | .123** | .158** | .087** | .073** | .133** |

| R2 change | .046** | .066** | .054** | .028* | .039** | .053** |

Note. R2 change refers to the addition of social predictors (social support, education, marital status and employment) to the model containing the biological and demographic predictors and psychological variables.

P < .05

P < .01

FCOPES: Family Crisis Oriented Personal Evaluation Scale

NYHA: New York Health Association

MI: myocardial infarction

What is the influence of biopsychosocial variables on the five FCOPES subscales?

Separate analyses were performed to examine the contributions of social variables beyond the biological, demographic, and psychological variables to each coping type (see Table 5). For the FCOPES subscales, the final model saw a significant improvement on the previous model. Men used social support coping strategies less frequently (P = .041) compared to women. As the time since their MIs (P = .029) and the amount of social support they received (P < .001) increased, they acquired social support coping strategies less frequently after controlling for biological, demographic, and psychosocial variables. The higher the patients’ anxiety levels (P = .011) and the less satisfied they were with their social support (P < .001), the less they used reframing coping strategies. Younger patients (P = .001), men (P = .038), and those less satisfied with social support (P = .036) sought spiritual support less frequently. Men (P = .035), employed patients (P = .015), and those who had completed secondary school (P = .036) used mobilizing frequently. The amount of social support received, satisfaction with social support, and education level were significant predictors of passive coping strategy use. The lower the amount of social support received (P = .033) and the less satisfied they were with their social support (P = .014), the higher the number of passive coping strategies used. Patients who had not completed secondary school (P = .016) used passive coping strategies more frequently compared to those who had completed secondary school.

DISCUSSION

The main purpose of this study was to examine whether biopsychosocial variables predict coping scores in post-MI patients. We found that the biopsychosocial variables predicted a small but significant amount of variance in total coping scores and each coping dimension measured using the FCOPES scale.

The amount of and satisfaction with social support were the only significant predictors of coping in post MI patients after adjusting for other biopsychosocial factors. Lower amounts of social support and satisfaction with social support predicted lower total FCOPES scores and greater use of passive coping strategies, as found in a previous study.14 In particular, less satisfaction with social support predicted a lower likelihood of seeking spiritual support. Seeking spiritual support could be related to religiosity as a supportive factor in patients’ coping16 and considered as a means of alleviating psychological distress.

The contribution of social support to coping is particularly interesting as most participants were married. The social support scale used in this study quantifies the amount of social support received based on a wider network as opposed to including spouse/significant others. The amount of social support received is based on the number of people patients feel they can access for assistance in difficult situations.26,28 Patient satisfaction with social support relates to the support received from these people. This concept of social support is much broader than marital status, and emphasizes a possible need for support beyond the nuclear family.15,33 Social support provides vital resources the individual can draw upon to survive or flourish until the end, whether this means cure or death.3,15,34 It is usually assumed that being embedded in a social network is also essential for people to feel good about themselves and their lives.33,34 When caring for patients post MI, health professionals need to consider whether patients with low levels of perceived social support should be closely monitored and whether, if possible, awareness of available social support resources should be enhanced. It is also important to assess specific coping strategies individuals use to cope with their disease.

By contrast, the other biopsychosocial factors tested were not significant predictors of total FCOPES. Nevertheless, in the final model of hierarchical regression analysis, age, sex, time since MI, anxiety, education, and employment were significant predictors of FCOPES subscale scores.

Age significantly predicted seeking spiritual support; the younger the patient, the less likely they were to seek spiritual support. This is inconsistent with McConnell and colleagues’ findings5 that indicated no significant difference in religious coping activities by age in first-time cardiac patients. They included only first-time MI patients, while 12.5% of patients in our study had previously experienced cardiac arrest or ventricular fibrillation; they also used different instruments to measure spirituality.5 In the FCOPES,22 the seeking spiritual support subscale provides a more general definition of the family's ability to acquire spiritual support. By contrast, McConnell and colleagues5 used a detailed tool that measures specific religious coping activities and includes six spiritual activity subscales. Therefore, the disparity between findings may be due to differences in participants and tools. Age was no longer a significant predictor of reframing coping strategy use when psychological and social variables were included in the model. This finding suggests that these psychological and social variables are associated with patient age and reframing coping strategy use.

In our study, sex predicted coping strategy use in three FCOPES subscales. Women used a higher number of positive coping strategies. Conversely, Bogg and colleagues4 reported that female patients used a higher number of negative coping strategies, such as avoidance and passive coping; in the current study, sex did not predict passive coping strategy use. This difference may be due to the proportion of women and the cultural diversity in the sample. In the current study, women from 30 sites in four countries comprised only 14.8% of participants, whereas 22.9% from one district general hospital were women in Bogg and colleagues’ study.4 Also, 97.2% of patients in this study had mild heart failure (NYHA class I or II). Women used the seeking spiritual support coping strategy more frequently compared to men; this subscale result is consistent with that of another study indicating higher spiritual coping activity scores in women.5

As the time since patients’ last MI increased, the amount of social support received decreased. According to Lazarus and Folkman's model,1 coping regulates distress during stressful events. In the acute MI period, patients experience greater stress. As social support acquisition refers to active engagement, patients may not need external help once the disease has stabilized. Patients’ adjustment to stressors over time may lead to reduced coping strategy use.21 This finding is consistent with results of longitudinal studies indicating that patients’ abilities to cope with negative emotions decreased for six months following MI.6

Sex and time since last MI were significant predictors of total FCOPES scores, both in the individual and final models after controlling for psychological and social predictors. Once the amount of social support received and satisfaction with social support variables were added to the final model, sex and time since last MI were no longer significant. These findings suggest that social support variables may be related to sex and time since last MI. Longitudinal studies examining long-term changes in social support in individuals who have experienced uncomplicated MIs would be useful. Women are less likely to receive lower social support or information regarding disease and rehabilitation compared to men.33 Sex-related differences in coping may also be associated with sex-related differences in social support. These findings emphasize the need to include more women in studies involving post-MI patients.

With regard to psychosocial variables and coping strategy use, in the current study anxious patients used the reframing coping strategy less frequently. Reframing is defined as the capacity to re-identify stressful events, rendering them more manageable;22 this is closely associated with problem-focused coping strategies. As anxious patients are distressed, they may experience difficulty in defining problems positively. Therefore, assessment of emotional status and encouragement of increased positive coping strategy use are important.25,34 A reciprocal relationship exists between inappropriate coping strategy use and psychological distress.10–13 For example, higher depressive symptom levels have been associated with negative coping strategy use.13 Whether inappropriate coping strategies influence psychological distress or vice versa remains unclear. Further research is required to examine this association and develop an intervention to prevent psychological distress and negative coping related to adverse outcomes in MI patients.

Patients who had completed secondary school used fewer mobilizing and negative coping strategies. Ross and Van Willigen35 suggested that education improves well-being; individuals with higher educational levels have access to better work and economic resources, which increase their sense of control and provide greater opportunities to form social relationships. The patients in this study tended to be well educated. The contribution made by education may have been more evident if there were a wider range of educational levels in the study. Indeed, previous studies have indicated that patients with higher education experience less post-MI psychological distress in the short and long term36 and display better psychosocial adjustment following the first MI.37 Therefore, patients with low educational levels may experience greater difficulty coping with their illness following the cardiac event. More attention is needed for patients with less education.

McConnell and colleagues5 found that marital status was associated with coping style, but this was not observed in relation to the FCOPES subscales in the current study. This may be due to the unique characteristics of the PR-HAT, which examined psychosocial differences between two treatment groups (partners who learned CPR or CPR and automated external defibrillation). This study limited enrolment to post-MI patients who lived with a supportive spouse or companion willing to undertake training for and use an automated external defibrillator.38 Consequently, there was little variance in marital status in our study.

Approximately 55.2% of patients were employed and used mobilizing coping less frequently compared to unemployed patients. The subscale for mobilizing family to acquire and accept help measures the family's ability to seek community resources and accept help from others.22 Seeking community assistance is an example of this coping strategy.39 Employed patients may have more resources in the workplace; therefore, they may not need to seek community resources.

The current study had several limitations. First, all patients lived with spouses or companions, which eliminated socially isolated individuals from the sample. Therefore, examination of the impact of social isolation was limited. Second, a group of relatively stable cardiac patients was included.18 Therefore, the results may not be applicable to patients with more severe heart disease. Additionally, the use of self-report questionnaires – which may be biased or inaccurate as participants evaluate their own coping skills, anxiety, and depression – also contributed to the limited generalizability of the results. As this study was based on cross-sectional data, causal relationships could not be established. Most study participants were white men who had completed secondary school; the lack of diversity may have restricted the generalizability of the results. Lastly, the explanatory power of the model for coping strategy use after MI was relatively low. This underscores the importance of other, unknown factors related to coping strategy use after MI. Accordingly, future studies should incorporate multiple biopsychosocial factors including economic status, resilience, personality, and cultural factors.

CONCLUSION

Nurses should be aware that patients’ coping strategies need to be taken into account when planning intervention before hospital discharge. With a greater understanding of amount and satisfaction with social support after MI, interventional studies are the next logical step to identify how effective social support from healthcare providers as well as family are on patients who are dissatisfied with support. Additionally, future nursing interventions to improve coping strategy use after MI should focus on the holistic interaction between biological-psychological-social domains rather than addressing them as separate aspects of the individual or environment.

Summary Statement.

What is already known about this topic?

The experience of a first-time acute myocardial infarction is a traumatic event and may influence well-being for a significant time period.

Coping strategies are a very delicate issue for people who have experienced myocardial infarction.

What this paper adds.

Social support was the only significant predictor of coping strategy use in post myocardial infarction patients after controlling for other biopsychosocial factors.

Social support may be related to sex and time since last myocardial infarction.

The implications of this paper for policy/practice/research/education.

Nurses should be aware that patients’ coping strategies need be taken into account when planning intervention before hospital discharge.

Nursing intervention strategies to improve coping strategy use after MI should focus on the holistic interaction between biological-psychological-social domains rather than addressing them as separate aspects of the individual or environment.

Acknowledgments

The PRHAT and HAT studies were partially supported by Grants R01 NR008550 from the National Institute of Nursing Research, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, United States, and Grant UO1-HL67972 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, United States. Also, This work were partially supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea Grant funded by the Korean Government (NRF-2015R1C1A1A01054200) and by the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy (MOTIE) and Korea Institute for Advancement of Technology (KIAT) through the International Cooperative R&D program.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. Springer Pub. Co.; New York: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Denollet J, Martens EJ, Nyklícek I, Conraads VM, de GB. Clinical events in coronary patients who report low distress: adverse effect of repressive coping. Health Psychology. 2008;27:302. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.3.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kristofferzon ML, Löfmark R, Carlsson M. Perceived coping, social support, and quality of life 1 month after myocardial infarction: a comparison between Swedish women and men. Heart & Lung. 2005;34:39–50. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bogg J, Thornton E, Bundred P. Gender variability in mood, quality of life and coping following primary myocardial infarction. Coronary Health Care. 2000;4:163–168. [Google Scholar]

- 5.McConnell TR, Trevino KM, Klinger TA. Demographic differences in religious coping after a first-time cardiac event. Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation and Prevention. 2011;31:298–302. doi: 10.1097/HCR.0b013e31821c41f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Hassan MA. Cognitive representations of symptoms of acute coronary syndrome and coping responses to the symptoms as correlates to prehospital delay in Omani women and men patients. Journal of Research in Nursing. 2015;20:82–93. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ginzburg K, Solomon Z, Bleich A. Repressive coping style, acute stress disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder after myocardial infarction. Psychosomatic Med. 2002;64:748–757. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000021949.04969.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gruszczyńska E. State affect and emotion-focused coping: examining correlated change and causality. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2011;26:103–119. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2011.633601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977;196:129–136. doi: 10.1126/science.847460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chiavarino C, Rabellino D, Ardito RB, et al. Emotional coping is a better predictor of cardiac prognosis than depression and anxiety. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2012;73:473–475. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2012.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Di Benedetto M, Lindner H, Hare DL, Kent S. The role of coping, anxiety, and stress in depression post-acute coronary syndrome. Psychology, Health & Medicine. 2007;12:460–469. doi: 10.1080/13548500601109334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sararoudi R, Maroofi M, Kheirabadi G, Gol MF, Zare F. Same coping styles related to reduction of anxiety and depressive symptoms among myocardial infarction patients. Koomesh. 2011;12:356–363. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Son H, Thomas SA, Friedmann E. The association between psychological distress and coping patterns in post-MI patients and their partners. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2012;21:2392–2394. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2012.04165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garnefski N, Kraaij V, Schroevers M, et al. Cognitive coping and goal adjustment after first-time myocardial infarction: Relationships with symptoms of depression. Behavioral Medicine. 2009;35:79–86. doi: 10.1080/08964280903232068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shen BJ, McCreary CP, Myers HF. Independent and mediated contributions of personality, coping, social support, and depressive symptoms to physical functioning outcome among patients in cardiac rehabilitation. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2004;27:39–62. doi: 10.1023/b:jobm.0000013643.36767.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hughes JW, Tomlinson A, Blumenthal JA, Davidson J, Sketch MH, Jr., Watkins LL. Social support and religiosity as coping strategies for anxiety in hospitalized cardiac patients. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2004;28:179–185. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2803_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salminen-Tuomaala M, Åstedt-Kurki P, Rekiaro M, Paavilainen E. Coping-Seeking lost control. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2012;11:289–296. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bardy GH, Lee KL, Mark DB, et al. Home use of automated external defibrillators for sudden cardiac arrest. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;358:1793–1804. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0801651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomas SA, Chapa DW, Friedmann E, et al. Depression in patients with heart failure: prevalence, pathophysiological mechanisms, and treatment. Critical Care Nurse. 2008;28:40–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Son H, Friedmann E, Thomas SA. Changes in depressive symptoms in spouses of post myocardial infarction patients. Asian Nursing Research (Korean Society of Nursing Science) 2012;6:158–165. doi: 10.1016/j.anr.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Son H, Thomas SA, Friedmann E. Longitudinal changes in coping for spouses of post–myocardial infarction patients. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2013;35:1011–1025. doi: 10.1177/0193945913484814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCubbin MA, McCubbin HI. Family stress theory and assessment: The T-double ABCX model of family adjustment and adaptation. In: McCubbin HI, Thompson AI, McCubbin MA, editors. Family Assessment Inventories for Research and Practice. University of Wisconsin Press; Madison, WI: 1987. pp. 3–32. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene RL, Vagg PR, Jacobs GA. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (Form Y) Consulting Psychologists Press; Palo Alto CA: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beck A, Steer R, Brown G. BDI-II: Beck Depression Inventory Manual. Psychological Corp.; San Antonio, TX: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frasure-Smith N, Lespérance F, Gravel G, Masson A, Juneau M, Bourassa MG. Long-term survival differences among low-anxious, high-anxious and repressive copers enrolled in the Montreal heart attack readjustment trial. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2002;64:571–579. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000021950.04969.f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frasure-Smith N, Lespérance F, Gravel G, et al. Social support, depression, and mortality during the first year after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2000;101:1919–1924. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.16.1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Delisle VC, Abbey SE, Beck AT, et al. The influence of somatic symptoms on Beck Depression Inventory scores in hospitalized postmyocardial infarction patients. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2012;57:752–758. doi: 10.1177/070674371205701207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sarason IG, Levine HM, Basham RB, Sarason BR. Assessing social support: the social support questionnaire. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1983;44:127–139. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barnes LL, Harp D, Jung WS. Reliability generalization of scores on the Spielberger state-trait anxiety inventory. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 2002;62:603–618. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dozois DJ, Covin R. The Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II), Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS), and Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation (BSS). In: Hersen M, editor. Comprehensive Handbook of Psychological Assessment. John Wiley; New York: 2004. pp. 50–69. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carney CE, Ulmer C, Edinger JD, Krystal AD, Knauss F. Assessing depression symptoms in those with insomnia: an examination of the Beck Depression Inventory second edition (BDI-II). Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2009;43:576–582. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leigh IW, Anthony-Tolbert S. Reliability of the BDI-II with deaf persons. Rehabilitation Psychology. 2001;46:195. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kristofferzon ML, Löfmark R, Carlsson M. Myocardial infarction: gender differences in coping and social support. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2003;44:360–374. doi: 10.1046/j.0309-2402.2003.02815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park CL, Fenster JR, Suresh D, Bliss DE. Social support, appraisals, and coping as predictors of depression in congestive heart failure patients. Psychological Health. 2006;21:773–789. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ross CE, Van Willigen M. Education and the subjective quality of life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1997;38:275–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Drory Y, Kravetz S, Hirschberger G. Long-term mental health of men after a first acute myocardial infarction. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2002;83:352–359. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2002.30616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Drory Y, Kravetz S, Florian V. Psychosocial adjustment in patients after a first acute myocardial infarction: The contribution of salutogenic and pathogenic variables. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 1999;80:811–818. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(99)90232-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thomas SA, Friedmann E, Lee HJ, Son H, Morton PG. HAT Investigators. Changes in anxiety and depression over 2 years in medically stable patients after myocardial infarction and their spouses in the Home Automatic External Defibrillator Trial (HAT): a longitudinal observational study. Heart. 2011;97:371–381. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2009.184119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaba E, Shanley E. Identification of coping strategies used by heart transplant recipients. British Journal of Nursing. 1996;6:858–862. doi: 10.12968/bjon.1997.6.15.858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]