Abstract

The CCN family of proteins is composed of six members, which are now well recognized as major players in fundamental biological processes. The first three CCN proteins discovered were designated CYR61, CTGF, and NOV because of the context in which they were identified. Both CYR61 and CTGF were discovered in normal cells, whereas NOV was identified in tumors. Soon after their discovery, it was established that they shared important and unique structural features and distinct biological properties. Based on these structural considerations, the three proteins were proposed to belong to a family that was designated CCN by P. Bork. Hence the CCN1, CCN2 and CCN3 acronyms. The family grew to six members a few years later with the description of three proteins WISP-1, WISP-2 and WISP-3 (CCN4, CCN5 and CCN6), that shared the same tetramodular and conserved structural features. With the functions of the CCN proteins being uncovered, this raised a nomenclature problem. A scientific committee convened in Saint Malo (France) proposed to apply the CCN nomenclature to the six members of the family. Although the unified nomenclature was proposed in order to avoid serious misconceptions and lack of precision associated with the use of the old acronyms, the acceptance of the new acronyms has taken time. In order to evaluate how the use of disparate nomenclatures have had an impact on the CCN protein field, we conducted a survey of the articles that have been published in this area since the discovery of the first CCN proteins and inception of the field. We report in this manuscript the confusion and serious deleterious scientific consequences that have stemmed from a disorganized usage of several unrelated acronyms. The conclusions that we have reached call for a unification that needs to overcome personal habits and feelings. Instead of allowing the CCN field to fully crystalize and gain the recognition that it deserves the usage of many different acronyms represents a danger that everyone must fight against in order to avoid its deliquescence. We hope that the considerations discussed in the present article will encourage all authors working in the CCN field to work jointly and succeed in building a strong and coherent CCN scientific community that will benefit all of us.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s12079-016-0340-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: PubMed, CCN proteins, CCN nomenclature, CTGF, CYR61, WISP, CCN1, CCN2, CCN3, CCN4, CCN5, CCN6

Introduction

The publications during the late 80’s and early 90’s, by the groups of Professor Raymond L. Erikson (Harvard University, Cambridge, USA), Dr. Rodrigo Bravo (Bristol Myers, Princeton, USA), Professor Lester lau (University of Illinois, Chicago USA), Professor Gary Grotendorst Universty of South Florida College of Medicine, Tampa, USA) and Professor Bernard Perbal (Institut Curie, Orsay, France) identified a new group of regulatory proteins that shared a highly conserved primary structure and a striking tetramodular organization but showed quite distinctive biological properties.

These early discoveries set the stage for the birth and growth of what is known today as the family of CCN proteins. They also boosted the development of a prolific original scientific research area that has given rise to hundreds of peered reviewed manuscripts which have demonstrated the involvement of CCN proteins in a wide array of critical biological functions. The progress made in the understanding of CCN proteins functions in normal and pathological conditions have opened new research avenues and interactive collaborative projects that argue for the existence and wide recognition of the CCN scientific field as a whole.

In this manuscript, we briefly review historical aspects underlying the emergence of the CCN field, and examine how the quantity and the quality of publications have increased over the past 25 years.

A careful examination of the different names usage in the field have revealed that the lack of unity in usage of acronyms has had a negative impact on the acception of the CCN family concept and has also impaired its wide recognition for some time. For example, the inclusion or deletion of a colon in an acronym can significantly alter the statistical evaluation of publication increase over time and may lead to a quite disturbing under estimation of scientific achievements.

Fortunately, it seems that the situation is improving. From a statistical point of view, the pace at which the number of publications in the CCN field has ramped up is the sign of its acceptance by the scientific community.

The data that we report in this manuscript sustains and reinforces the need for an even wider usage of the CCN terminology and for its full recognition by the official nomenclature committees.

Material and methods

The analysis of articles that was performed in this work was based on the publications indexed on the PubMed database available at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed.

PubMed is a service of the US National Library of Medicine that was developed by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) at the National Library of Medicine (NLM). It has been available since 1996.

Presently it comprises more than 26 million citations. It includes references to biomedical literature from MEDLINE indexed journal, life science journals and manuscripts that have been deposited in PMC, and online books (NCBI Bookshelf). As PubMed citations include links to full-text content from PubMed Central, and publisher web sites, with in-process citations and Ahead of Print citations and references to selected life sciences journals that are not in MEDLINE its coverage is broader than that of PubMed Central (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/about/intro/), another free archive of biomedical and life sciences journal literature launched in 2000 at the U.S. National Institutes of Health’s National Library of Medicine (NIH/NLM). For more information see FAQ: PubMed® (https://www.nlm.nih.gov/services/pubmed.html) and MEDLINE, PubMed, and PMC (PubMed Central): How are they different? (https://www.nlm.nih.gov/pubs/factsheets/dif_med_pub.html).

PubMed offers the options of conducting a regular search and an advanced search. Both have been used here. The advanced search builder allows use of combinations of filters including selection of title/abstract T/ABS), full text (text word), and all fields. All of them were used for each member of the CCN family of proteins. In each case, searches were based either on the original acronyms or on the CCN-based acronyms recommended by the Steering Committee (Brigstock et al. 2003) that was constituted at the first Workshop on the CCN family of Genes.

Zotero (http://www.zotero.org) was used to perform the compilations of the references obtained for the group of CCN proteins, and to draw the listing that were used to perform final manual screenings.

The results reported in the present manuscript cover searches that were run until July 9, 2016.

From CEF10 to the concept of a CCN family of proteins

As detailed accounts of the historical base of the CCN family have previously been published (Perbal 2001, 2013) we will focus in this article on aspects that are helpful to fully appreciate the spectacular pace at which the CCN field have evolved, leading to the present understanding of the biology of the CCN family of proteins.

The very roots of the CCN family saga are found in a manuscript published a little more than 25 years ago, when an immediate early protein (CEF10) discovered in R.L. Erikson’s laboratory was reported to be induced upon production of the pp60 v-src oncogene that was expressed in Rous sarcoma virus (RSV)-infected chicken embryo fibroblasts and upon serum stimulation of starved fibroblastic cells (Simmons et al. 1989).

A year later, L. Lau’s search for factors involved in the regulation of cell growth led to the characterization of a cystein-rich protein (CYR61) encoded by an immediate early gene whose transcription was triggered within a few minutes following growth induction of quiescent murine BABL/c 3 T3 mouse cells upon addition of serum to the culture medium (O’Brien et al. 1990). Although CYR61 was the murine ortholog of CEF10, the regulation of their expression in murine and chicken cells was quite distinct.

In those years, a considerable attention was given to the roles of the factors encoded by immediate early genes (IEGs) among which were several now-famous transcription factors such as c-myc, c-jun and fos, but also secreted proteins with low affinity to platelet factors, cytoskeletal and extracellular matrix proteins.

Along this line, the characterization of murine proteins induced by serum stimulation of starved cells permitted the group of R. Bravo to identify a secreted cystein-rich protein that was designated FISP12 (Ryseck et al. 1991).

A few month later, G. Grotendorst’s study of chemotactic and mitogenic factors secreted by cultured human endothelial cells (Bradham et al. 1991) identified the Connective Tissue Growth Factor (CTGF) as the mammalian orthologue of FISP12.

In a completely different type of approach, initiated by B. Perbal to identify the events leading to nephroblastomas in a chicken model using a molecular clone of Myeloblastosis Associated Virus Type1 (MAV-1) that specically induced nephroblastoma in day old chicken (Perbal 1995), a MAV proviral integration was found to activate a new gene (NOV) that was expressed in several independent avian nephroblastomas (Joliot et al. 1992). However, the human orthologue of nov that was cloned later in the same laboratory was not found to be overexpressed in human nephroblastomas (Wilms’ tumors) (Chevalier et al. 1998).

At that time, the description of protein families1 by physical chemists involved in the creation of the first comprehensive protein databases, was very trendy. Members of these families were proteins that shared common features, either from an evolutionary or a functional standpoint. If the novel biological properties of CEF10 were obviously not sufficient to suggest the existence of a new family of proteins, the conserved primary sequence and tetramodular organization of CYR61, FISP12/CTGF and NOV indeed led P. Bork to propose that they were evolutionarilly related and constituted a new family of functionally related regulatory proteins, that was designated CCN (an acronym that he coined from the first letter of the three proteins names).

In 1997 and 1998, three manuscripts reported the identification of new proteins that shared the structural features of CCN proteins and were therefore considered as new members of the family.

The first of these communications was published in February 1998 by the group of J. Yokota (National Insitute of Genetics, Shizuoka, Japan) in the Journal of Experimental Medicine. It reported the identification of Elm1, a new member of the CCN family acting as an in vivo suppressor of tumor growth and metastatic potential of murine melanoma cells (Hashimoto et al. 1998).

Shortly after this communication, a manuscript published in October 1998 by the goup of Lian (Dana Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, USA) reported the isolation of rCOP-1, a new CCN protein whose expression was abolished upon rat cell transformation. The rCOP-1 protein was shown to lack the C-terminal module contained in all other CCN proteins (Zhang et al. 1998).

Finally, in December 1998, D. Pennica’s group published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, the identification of three human orthologs to the previously described CCN proteins (Pennica et al. 1998). Their expression was up-regulated in Wnt-1 transformed cells and was aberrantly expressed in human colon cancers. A xenopus CYR61 was later identified (Latinkic et al. 2003).

At the dawn of the twenty-first century, the human CCN family of proteins appeared to contain 6 members. The sequence of the human genome published in 2001 confirmed these findings.

Surprisingly, the manuscripts reporting the isolation of Cef10, Fisp-12, Elm1 and rCOP-1 were not given the full credit that they deserved, even though they reported a set of biological properties which helped getting a grip on the functional complexity of the CCN family of proteins.

In our opinion, it is very disappointing that many scientists in the CCN field, not only among the younger generation, ignore the existence and seminal importance of these manuscripts.

In 2008, there was an attempt, based on structural features, to include the CCN proteins into an insulin-like growth factor superfamily (Baxter et al. 1998). Aside from the fact that this proposal created confusion in the nomenclature, the concept, which did not stand on a solid basis (Grotendorst et al. 2000), has been abandonned.

The needs for a new nomenclature

In 2000, upon the intiative of B. Perbal, the first International Workshop on the CCN family of Genes was held in Saint-Malo France.2 This unique event gathered all the leaders in the CCN field.

After thorough discussions about the biological importance of the CCN proteins, a Steering Committee headed by B. Perbal, was formed to propose both a better communication between laboratories, to promote collaborative projects, and a strategy to get the CCN field recognized in the scientific community.

Along this line, the International CCN society (ICCNS) was created, soon followed by the creation of the Cell Communication and Signaling online Journal (which has become the Journal of Cell Communication and Signaling published by Springer) as the official media of the ICCNS.

On the occasion of the second Workshop,3 a insightful discussion was intiated regarding the accuracy and relevance of the various names given to the CCN proteins, as it appeared that some of them were misleading or inappropriate.

The progress that was made by several groups in deciphering the biological properties of the CCN proteins raised issues regarding the terminology used to designate these proteins.

A striking example in this vein is provided by the CTGF acronym calling for the corresponding protein being a growth factor for connective tissue.

At the time the human protein (CTGF) was discovered, the expression of the murine ortholog (Fisp12) had previously been shown to be induced by growth-factor-stimulated NIH 3 T3 cells, making it the product of an « immediate early » type of response (see above).

CTGF was reported to be responsible for the « the PDGF-related mitoattractant activity present in the endothelial cell-conditioned media ».

Even though the protein indeed activates cell proliferation in cooperation with other cytokines and ligands, there is published evidence that does not support CTGF being a growth factor by itself (Lau 2016).

Since CTGF is a very « sticky » molecule it is difficult to obtain pure preparations deprived of contaminants such as HBEGF, endotoxin, TGF beta possibly PDGF which may be responsible for some of the activities initially ascribed to CTGF. In completely pure preparations these activities are lost. It is well understood by experts that CTGF can bind many molecules with growth-factor like properties (A. Leask personal communication).

Therefore, the usage of the CTGF acronym does not appear to be accurate and is rather misleading.

It is quite remarkable that a considerable number of groups working on this protein have kept using the CTGF acronym instead of CCN2 (see discussion section).

The NOV nomenclature was also found to be inappropriate and scientifically misleading.

As previously discussed, the NOV acronym was used to highlight the fact that the insertion of MAV-1(N) in the genome of day old chickens induced nephroblastmas showing an overexpression of a cystein-rich cell growth inhibitor. At the time it was discovered, the NOV protein was the first member of the CCN family that was not an immediate early protein. It was later shown to be inhibit tumor cells growth, both ex vivo and in vivo.

The analysis of a greater number of tumors and the re-examination of « nov » expression in embryonic and adult fibroblasts showed that the protein was not overexpressed in all avian nephroblastomas nor in the human Wilm’s tumors (Perbal 1994, 2001). Furthermore, later studies indicated that the « nov » gene was not a preferential integration site for MAV-1(N) (Li et al. 2006).

To these considerations was added the fact that « nov » was the acronym used for the 23 members of the novobiocin gene cluster (Steffensky et al. 2000), and part of the bacterial nomenclature system. The circumstances called for a new designation.

Both the « nov » acronym and « novH » which had been temporarily used, became obsolete and were abandonned (Perbal 2006) to avoid scientific confusion and the burial of nov/ccn publications among thousands of unrelated citations.4

At that time of the Second Workshop, the CCN proteins already showed a wide variety of biological functions, even though a few of them might appear to be more prominent or common to several members.

Therefore, a problem arose when the participants at the meeting tried to coin a name that would suggest a property or a function common to these proteins. Our present knowledge indeed confirms that a name with a « functional » note would have restricted the biological importance of the CCN proteins.

The Steering Committee proposed to switch from the old names to a unified CCN acronym system in which the numbering of the proteins correspond to the order of their description in mammals. Hence CYR61 became CCN1, CTGF became CCN2, NOV became CCN3, and WIPS-1 to −3 became CCN4 to 6. The proposal for a unified nomenclature (Brigstock et al. 2003) was published shortly after it was adopted by the attendees in the second International Workshop of the CCN family of Genes.

In order to evaluate the pace in progression of the CCN field, and how the acronyms were being adopted among the scientific community publishing in the field, we have now run a survey of the increase in the numbers of publications over the past 25 years.

We also followed how the usage of the old and newer acronyms compared and evolved with time since the inception of the unifying CCN nomenclature.

A unified nomenclature as a mean to avoid scientific confusion

In spite of the biological considerations that led to the new nomenclature being endorsed by a large number of leading laboratories in the field, a significant number of scientists kept on using the original inappropriate names (A).

As we show in this manuscript, the confusion not only stems from colleagues resisting the use of the CCN acronym, but also from a misuse of the original terminologies (B).

-

A)

Compilations of articles published for the 6 CCN proteins

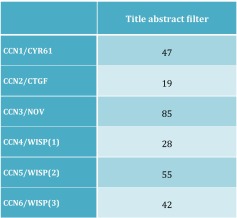

For each of the 6 proteins, we first collected from PubMed the list of articles that were pulled out with an advanced search performed with either the « all fields » or « Title/Abstract » filters, and either the « CCN variable » or the « original acronym » variable.

Since we realized that the « all fields » filter was also pulling out the manuscripts in which the « CCN » and « old acronym » variables were cited in the list of references, or as part of the CCN family description in the text, we selected for our subsequent work, the values corresponding to the « Title/Abstract » filtering5 which, in our opinion, reflect more accurately the acronym usage.

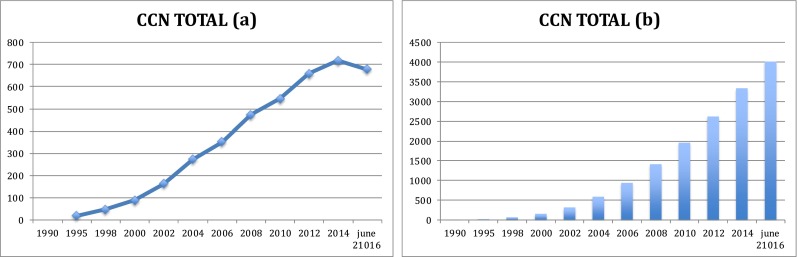

As a first step in our study, we made a compilation of all the manuscripts that were pulled out with the filters CCN1 to 6, CTGF, CYR61, NOV,6 WISP-1 to 3,7 as described in Materials and Methods. A little more than 5000 references were obtained and screened with Zotero in order to eliminate about a thousand duplicates. The resulting list of 4013 references8 was used to analyze the rate at which the total amount of publications dealing with the CCN proteins evolved with time since their discovery.

The results reported in Table 1 and Fig. 1, revealed that the publications reporting on the biology of CCN proteins accumulated at a remarkable pace, with a sharp increase over the past 10 years (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Total amount of CCN publications

| Number per time-period | Incremental numbers | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1990–1995 | 18 | 1990 | 0 |

| 1996–1998 | 48 | 1995 | 18 |

| 1999–2000 | 88 | 1998 | 66 |

| 2001–2002 | 163 | 2000 | 154 |

| 2003–2004 | 272 | 2002 | 317 |

| 2005–2006 | 351 | 2004 | 589 |

| 2007–2008 | 473 | 2006 | 940 |

| 2009–2010 | 545 | 2008 | 1413 |

| 2011–2012 | 659 | 2010 | 1958 |

| 2013–2014 | 718 | 2012 | 2617 |

| 2015/06–2016 | 678 | 2014 | 3335 |

| Total | 4013 | 06–2016 | 4013 |

The evolution of number of publications in the CCN field since its inception in 1990 with the publication of the first manuscript on a CCN protein. The total of 4013 publications was obtained after elimination of all duplicates that were contained in a compilation of all articles pulled out with filters corresponding to the various acronyms of the six members of the CCN family

Fig. 1.

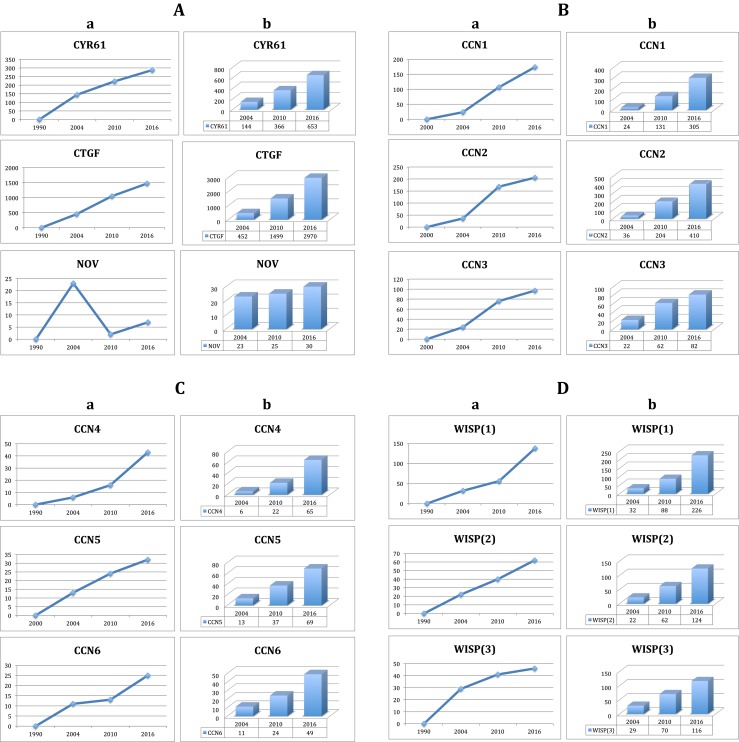

Global evolution of the number of manuscripts reporting on members of the CCN family of proteins. Panel (a) Each value of the curve corresponds to the numbers of publications published during the two-year time interval. For example, the value for 2006 corresponds to the number of publications published between 2004 and 2006 inclusive. Panel (b) The histogram is an incremental representation of the number of publications over time. For example, the value for 2006 corresponds to the total number of publications published between 1990 and 2006 inclusive

Fig. 2.

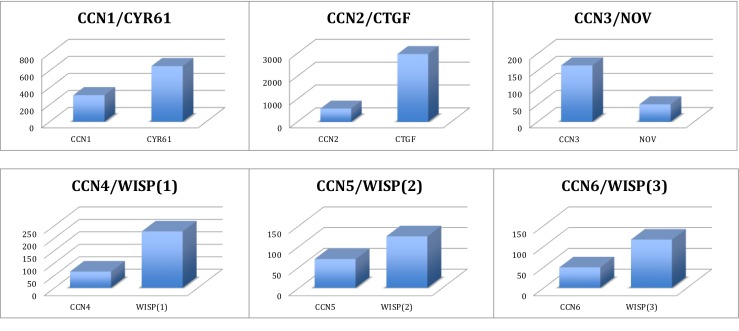

CCN Proteins articles produced since 1990. For each couple of acronyms the histogram represents the total number of publications produced since 1990. The value provided for each of the WISP proteins is the sum of values for WISP without and with the hyphen [for example WISP(1) = WISP1 + WISP-1] (see text)

A set of independent searches performed with each individual acronym on PubMed were used to evaluate the proportion of articles using the different nomenclatures. The results reported indicate the total number of articles citing either the original or the unified nomenclature. The ratios of each acronym (Table 2) indicate that the CCN1, CCN5 and CCN6 acronyms were used in about 50 % of all publications dealing with these genes. The CCN3 value is exceptionally high because it was quickly used, in place of the Nov acronyms.9 The CCN4 usage appeared to be much lower.

Table 2.

Proportion of CCN acronyms over original acronyms

The numbers provided are expressed as a percentage of articles using the acronym suggested by the unified nomenclature for each member of the CCN family

As discussed in the text, the wobble use of WISP acronyms with and without an hyphen leads to confusion. For the purpose of this article, we used a WISP designation which refers to both acronyms [for example, WISP(1) = WISP1 + WISP-1]

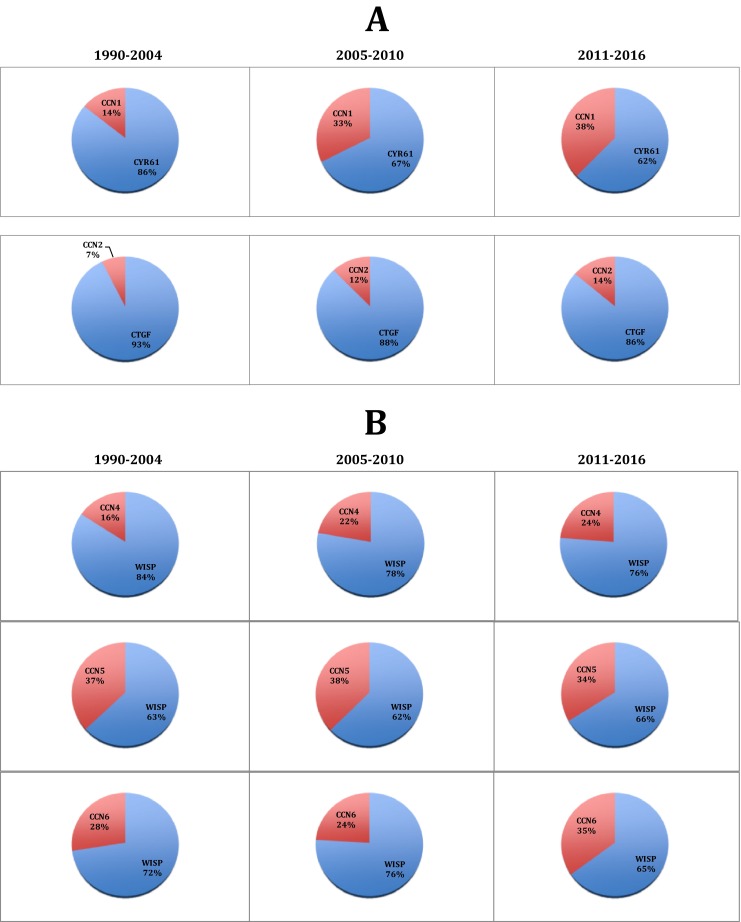

A comparison of the various acronyms’ usage over time is illustrated in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Representation of CCN proteins articles produced over time. For each protein, panels (a) refers to the two-year time interval periods and panels (b) is showing incremental values

In each case, the rate of publications using the different acronyms was highly comparable, except for CCN6 which showed a decrease between 2005 to 2010, and for NOV as the result of 5 publications recently published by Chinese groups who appear to ignore the recommendations for a unified CCN nomenclature.

We next sought to evaluate the impact and acceptance of the CCN nomenclature among the laboratories publishing with the original acronyms.

For this purpose, we analyzed, for each member, how the number of articles using both the original and the CCN nomenclatures evolved with time. The results, expressed as the percentage of manuscripts with the original acronyms in which the CCN nomenclature is also used (Fig. 4) showed a significant increase in the evolution of CCN acronyms usage over time signaling a wide recognition for the use of the CCN nomenclature.

-

B)

Problems generated from a wobble nomenclature

Fig. 4.

Increase of CCN acronym usage among manuscripts using the original acronyms. For each protein, the ratio of articles using the CCN acronyms among all the articles using the original acronym was calculated for 3 time intervals. As discussed in the text, CCN3, which is not represented here, is a particular case, as the usage of NOV has been quickly abandoned

The statistics that we provide below show examples of problems that are encountered in the evaluation of the CCN field impact as a whole.

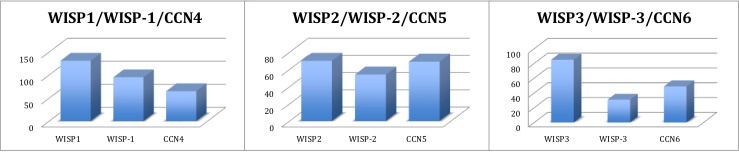

In a detailed analysis of the article numbers referring to the members of the WISP group of proteins, we realized that for each of them, we could identify two types of manuscripts: those that used an acronym deprived of a hyphen, instead the original acronym.10

Although we thought, at the first glance, that the incidence might be minimal, it turned out that the two groups did not overlap extensively and corresponded to specific articles dealing with the same proteins.

In order to get a better insight into the content of the two categories, we ran a detailed analysis of the articles reporting on the first WISP member which is designated as either WISP1 or WISP-1(original acronym) (Fig. 5).

Searching the database with a « WISP1 » filter

Fig. 5.

The wobble usage of WISP1 and WISP-1 acronyms. For each of the three family members, the histograms represent the numbers of articles using either the original WISP-1 acronym introduced by Pennica et al. (1998) or the WISP1 acronym that is found on the HGNC web site. For a comparison, the number of articles using the CCN nomenclature has been indicated in each panel

We first used WISP1 with no additional filter (or with the « all fields » filter) pulled out 198 articles.

In order to better understand the significance of the number of citations obtained when the « All fields filter » filter was used, we screened the 198 articles one by one.11

The results were rather unexpected as we could identify

44 articles referring to WISP-1,

6 articles whose topic were unrelated to WISP but cited WISP

Among them, the communications by Chien et al. (2011) on CCN2/CTGF cited WISP1 and WISP-1 in the references, Hou et al. (2013) on CCN4 cited WISP-1,-2,-3 in the introduction, and Liu et al. (2013a, b) cited WISP1 and WISP-1,-2–3 in the references.

The paper by Ji et al. (2015) on WISP-2 also referred to WISP-1, and the article by Hurvitz et al. (1999) on WISP3 quoted WISP1 in the description of other WISP proteins related to WISP3.

3 articles dealing with topics totally unrelated to the WISP field.

The paper by White et al. on cardiac regeneration (2015), by Cheng et al. on Broussochalcone A and nitric oxyde synthetase (2001) and by Vargas et al. on Wasp-1 (2015) which were pulled out with a WISP1 filter did not mention WISP at all.

2 articles reporting on Elm1. The manuscript by Hashimoto et al. (identification of Elm1 in Hashimoto et al. 1998), was published before the publication of the manuscript by Pennica et al. reporting the characterization of the three WISP proteins. Surprisingly, the Hashimoto paper pulled out citing WISP1, is obviously wrong, as we have checked in the text of the publication. The other manuscript that reported on the rat ortholog of Elm1 (Sleeman et al. 2000) was pulled out with a « wnt-induced secreted protein-1 » filter.

3 articles by Su et al. (review on CCN family - 2002), Zhang et al. (wnt pathway in irradiated lung fibroblasts –Zhang et al. 2016) Yu et al. (WISP1 and radiosensitivity of glioma cells – 2014) were published in Chinese.

The original list of 198 articles drawn from a WISP1 filtering, also contained 26 reviews, of which 12 were relevant to the WISP1 signaling and/or biological properties. None of the 8 reviews by Katoh on Wnt-related signaling, were specifically addressing WISP1 biological properties. Six reviews by Maiese were also considered as not directly relevant.

We draw from these results that among the 198 articles pulled out from the PubMed data base with a WISP1 filter, there were 114 research articles (including 3 articles in Chinese, whose content was not available in english).

When a similar search was performed with the T/ABS (title abstract) filter, 133 articles were pulled out, with much less noise referencing to Wisp-1. A cross-check with the WISP1 publications contained after processing of within the list of 198 (all fields filter) indicated that 10 items were missing in the T/ABS list of 131, which contained 8 additional irrelevant articles.

-

2)

Searching the database with a « WISP-1 » filter

A similar search using the WISP-1filter pulled out 95 articles, both in the listings obtained through« all fields » or T/ABS selection.

A manual verification of the manuscripts contained in the T/ABS listing of WISP-1 articles revealed:

8 articles referring to WISP1

10 articles whose topic was unrelated to WISP-1

Among them, Borkham-Kamphorst et al. (2012) on CCN3, Chen et al. , Leu et al., Greskiewicz et al., Mo et al. (2000, 2001, 2002, 2002) on CCN1/CYR61, Lin et al. (2003, 2005) on CCN3 only quoted WISP-1 as belonging to the CCN family of proteins.

One article on WISP-3 (Thorstensen et al. 2001) mentioned the homology of WISP-3 with Wisp-1.

One article on CCN4 and CCl4-induced fibrosis (Li et al. 2015) quoted WISP-1 as a member of the CCN family of proteins and in one reference.

The list of 95 articles drawn from a WISP-1 filtering, also contained 10 reviews of which 4 presented general features of the CCN family of proteins, 3 were reviewing biological properties of CTGF and CYR61 - CCN4 - and CCN3; one was discussing the generation of WISP-1 variants, one quoted CCN proteins in the context of cellular communication, and one reviewed the role of Wnt signaling in osteoarthritis.

We draw from these results that among the 95 articles pulled out from the PubMed data base with a WISP-1 filter, there were 66 research articles (plus 1 article in Chinese, whose content was not available in english).

The consequences of this wobble acronym usage are two-fold.

Although the articles using the WISP-1 or WISP1 acronym report data related to the same protein, they are different ones and are not pulled out from searches on PubMed using only one acronym as a filter.

Most importantly, those in the scientific community who will rely on searches performed with the acronym that they use, will miss a considerable amount of information.

Representation of the CCN proteins field in cell biology

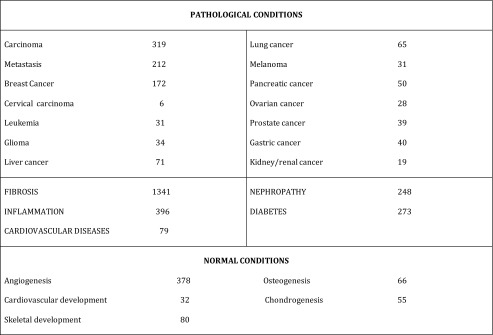

In order to briefly assess whether studying the biological properties of the CCN family of Proteins constitutes a scientific field as a whole, we sought to determine how the manuscripts citing CCN proteins were distributed among various scientific domains.

A quick preliminary survey established that CCN proteins were associated to several major aspects of cell biology in normal and pathological conditions (Table 3).

Table 3.

Numbers of manuscripts reporting on CCN Proteins in normal and pathological conditions

Without going into detailed mechanisms, we took advantage of the full CCN publications compilation that we had drawn from PubMed, to run a quick survey of the manuscripts’s trends among the various topics of interest.

Among the 4000 published articles quoting CCN proteins, cancer and fibrosis represented two major groups of 662 and 1341 respectively (Table 3).

Among the number of CCN articles which reported on molecular aspects of cancer research (Planque and Perbal 2003; Li et al. 2015), metastasis and breast cancer were two major topics.

Several CCN proteins playing critical roles in other cancers (see update by Yeger and Perbal, in this issue) were found to be involved in inflammation processes (see Table 3) which are believed to precondition the tissue field for cancer development.

The closely related fields of nephropathy and diabetes were also topics of abundant publications related to CCN proteins biology (Klaassen et al. 2015); the involvement of CCN proteins in hematopoietic diseases (see S. Irvine in this issue) cardiovascular diseases and atherosclerosis also appears to be well documented (Zhang et al. 2016).

Fibrosis in all its forms, has been and remains the major topic of studies involving CCN proteins. Many publications established that CCN2/CTGF is a profibrotic molecule, in several different systems (Charrier and Brigstock 2013; Mason 2013; Leask 2015). Translational medical applications are expected to appear soon (Perbal 2003; Jun and Lau 2011; Leask 2013).

The involvement of CCN proteins and their cross regulation in normal biological processes has also been the subject of many key articles in fields such as angiogenesis, skeletal development and bone development (Holbourn et al. 2008 ; Kawaki et al. 2008; Hall-Glenn and Lyons 2011; McCallum and Irvine 2009).

It appears that the CCN family of proteins biology has now established itself as an essential field related to cell signaling and regulation of cell behavior in normal and pathological conditions.

Discussion

Publications and meetings are two pillars of scientific communication.

It goes without saying that efficient communication requires a common language.

Although these two acknowledgments probably sound quite obvious to most researchers and may sound like « kicking down an open door », one cannot but accept that a significant mass of new information is lost in an enormous amount of results that are contained in the thousands of specialized journals whose number has exploded since the advent of online publishing.

This is a fact and we will not easily reach a point when scientific information is made easily accessible to everyone.

On the top of purely technical and scientific problems of which we have shown some examples in this manuscript, many economic, political and social aspects, which are out of scope here, are not helping to grow the basis of a universal efficient communication.

In an attempt to get a « snapshot » of how the CCN proteins field, in which we have actively promoted communication, has evolved during the past two decades, we have run a survey of the CCN-proteins-related publications indexed on PubMed which is recognized as one of the most reliable and consulted electronic worldwide accessible, database for biological sciences.

Our motivations stemmed from the frustrating observations that, even though a dedicated media (The Journal of Cell Communication and Signaling) and a biennial International meeting (International Workshop on the CCN family of Genes) were made available to all scientists working or having any interest in the CCN proteins, the crystalization of the field was only partial.

The analyses that we have performed highlighted very encouraging trends.

The CCN family of proteins has served as a foundation for the establishment of a new field, a field which is recognized as a whole by other societies such as the American Society for Matrix Biology, with which interactions have been established.

The use of revisited acronyms that are no longer ambiguous has been helpful along this way, because it has helped crystalize results that would otherwise be dispersed in an abundant literature dealing with matrix biology.

Furthermore, the increasing number of publications reporting on the CCN family of proteins, has been seminal to the demonstration that this group of proteins constitute a unique example of new inter-cellular signaling factors, whose functions complement and compete each others, in the regulatory process of cell communication with their surrounding microenvironment.

Sadly, the results of our survey clearly indicated that the use of the various acronyms which were given to the CCN proteins upon their discovery is deleterious to the field as a few of them bear wrong concepts and are misleading.

In spite of this caveats, many scientists kept on publishing with the old nomenclature and missed the opportunity to belong, and participate to an extended family of researchers who actively communicate, exchange reagents and techniques, and meet on a regular basis to stimulate one to one direct communication.

It is frequent in Science that different names are given to the same molecule by independent researchers. Sometimes both keep on using the name they initially used with the hope that it will become the standard. Also some researchers fear to change the name of the gene they discovered because the system is such that papers published with an acronym may be « lost in translation » to a new referencing. In any case, the maintenance of different acronyms calling for the same entity has never been helpful.

Fortunately, when scientists realize that the main goal is progress, a consensus is generally reached.12

Aside from non-scientific personal or professional ego-related motivations that are not to be considered here, we see two main reasons - a questionable referencing by reagents providers and publications indexation systems - that account for not switching to the unified CCN nomenclature.

The official referencing for genes and proteins is conducted by the HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee.13

Although the CCN1 to 5 nomenclature indeed shows on the HGNC web site,14 as gene symbol aliases - i.e. appearing with small characters, opposed to the large ones used for initial acronyms - it appears that for a long time most reagents providers have kept using only the original nomenclature, in spite of the publication of the proposal for a unified nomenclature, based on solid scientific considerations.

The case of CTGF, is somewhat more complex, due to the fact that the only company officially interested in the biological properties of this gene15 was providing antibodies raised against this protein but was never ready to change its acronym, even though it was reported to be misleading. Anyone using their source of antibody had to use the CTGF acronym.

Unfortunately, the problem was not restricted to CCN2, as the HGNC itself misuses the original acronym coined by Pennica et al. (1998) by removing the hyphen between WISP and the gene number (see for example on the HGNC web site WISP2 instead of WISP-2, for CCN5).

At first glance, this improper designation, and the use of old acronyms may seem inocuous, but they have quite severe consequences, as we have shown in this manuscript.

The usage of slightly different acronyms for the WISP proteins (with and without hyphen),16 and the conservation of acronyms that bear the wrong concept (such as CTGF) result in a general confusion that is scientifically deleterious for a whole field which is expanding at a fast pace and one proving to be critical for understanding cell signaling in normal and pathological conditions.

The other problems that we have documented in this article stem from the usage of the PubMed database a browser to pull out articles pubished in the CCN field.

Aside from the different names that are used and that give rise to partial unrelated listings, we also realized the considerable impact of the spelling that is used when searching (and entering) information on this database.

Although PubMed, is a very unique database that provides the most comprehensive indexing of scientific publications, it is obviously not adapted for a critical screen and identification of manuscripts.

In any case, the best algorithm will always suffer from the disparate and non consensual use of acronyms.

We have noted during the preparation of this manuscript that not only are the consequences loss of citations and information, but the confusion also results in a split community that, on the contrary, would needs everyone to be aware of the work and advances from others.

We do not believe that researchers can find any advantage in standing out of a scientific community working on the same proteins.

Considering the shrinking funding from which we all suffer, we believe that using a nomenclature which is not misleading can only improve progress that will be made in the field. As explained above, the group of CCN leaders and other participants to the first International Workshop on the CCN family of genes carefully considered several options for such a nomenclature and all agreed that, considering the wide variety of functions and biological properties assigned to the CCN proteins, the best choice was to avoid an acronym that would restrain its biological significance.

The proposal for a unified nomenclature combined with efforts that we have deployed to organize meetings along with an official journal for reporting CCN research were meant to consolidate the relationships between researchers who would otherwise ignore each other.

Being part of a community is an essential aspect of modern science.

On a very practical standpoint, researchers have nothing to gain from an under-evaluation of their published work. The confusion created by lax acronym usage can only shed bad light on evaluation of scientists careers.

We have also noted with pleasure during the preparation of this manuscript that Chinese groups have joined the field. The potentials assigned to the CCN proteins travel worldwide, and we recognize that it can bring our community an unexpected boost.

Unfortunately we also noticed that a few of them use the old « NOV » acronym that was abandoned partly because it makes impossible any kind of productive bibliographic search.

This is the perfect example of wasted information.

Perhaps they ignored the unified nomenclature proposal, but this situation also raises a very deep concern that has already been addressed in these columns, that is about the qualifications of the reviewers analyzing manuscripts that are submitted to regular and online journals that are burgeoning. As already discussed flawed reviewing is adding on problems. Unfortunately there are many examples of publications that either report already published or insufficiently consolidated data. This is permitted by lax reviewing of papers but also by the use of a particular acronym that will, in the end, not permit a critical survey of the litterature.

It is also the responsibility of the editors to help scientists using a coherent unified nomenclature and pay attention to these aspects in order to avoid collapse of the whole system.

Unification of the field requires speaking the same language and knowing better the work performed by others instead of being limited to a small corner of the same field.

In order to ease a smooth transition in acronym usage we had proposed that manuscripts reporting on CCN research may indicate the dual acronym, at least until the unified nomenclature is fully used. For example, colleagues publishing on CTGF could mention CCN2/CTGF or CTGF/CCN2 in their manuscripts. The articles which followed this suggestion were indeed pulled out in our searches.

We are convinced that the whole community will benefit from everybody « playing the same game », and we would like to take this opportunity to renew our suggestion and invite all researchers working in the great field of CCN research to join us either at the CCN biennial meetings17 or in print.18

Electronic supplementary material

(RTF 993 kb)

(DOCX 48 kb)

(DOCX 43 kb)

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Yeger for critical reading of the manuscript. Thanks are due to Dr.Leask (University of Western Ontario, Ontario, Canada) and Dr. Rheims (Laboratório Especial de Coleções Zoológicas, São Paulo, Brasil) for their help and suggestions.

Footnotes

According to the Merriam-Webster dictionnary, a family may be « a group of things related by common characteristics, as a closely related series of elements or chemical compounds »

The first International Workshop on the CCN Family of Genes was organized by A. Perbal and B. Perbal (co-organizer L. Lau) and held on 17–19 October 2000. For a review of the communications presented at the workshop see « Report and abstracts on the first international workshop on the CCN family of genes » by Ayer-Lelievre C, Brigstock D, Lau L, Pennica D, Perbal B, Yeger H.(2001) Mol Pathol. Apr;54(2):105–20.

The second International Workshop on the CCN family of Genes held in Saint Malo (Oct 20–23, 2002) was organized by L. Lau and B. Perbal (Administration A. Perbal). For an account of the communications presented a this workshop, see « Report on the second international workshop on the CCN family of genes » by Perbal B, Brigstock DR, Lau LF. (2003) Mol Pathol. Apr;56(2):80–5.

At the time this article is being written up, a PubMed search performed in « all fields » with « nov » pulled out 1,939,669 references, and a search performed on Title/Abstract pulled out 21,064 references ! This is not so surprising as articles containing nov. for « november » and nov for new genus « nov.gen » and new species « nov. spe. » are pulled out with a search using the nov filter.

In spite of the fact that some numbers pulled out with « Title/abstract » were slightly lower than those obtained with the « All fields » it did not significantly alter the overall variations in the publication trends.

Since the use of « nov » and « novH », filters provided sets of articles that were different, we have pulled all of them under a single category designated NOV. The numbers obtained with the « CCN3/nov », and « nov/CCN3 » filters have been pooled with the CCN3 values.

As discussed later in the results section, 6 different WISP acronyms are currently used, and are found in different articles. For the sake of simplicity, we have used in our presentation a provisional WISP (1), (2), (3) denomination that encompasses both categories (with and without hyphen) for each one of the 3 proteins.

The complete rtf listing (361 pages) is available in Supplementary Data ESM1

Since B. Perbal, signed 40 % (67/165) of the total CCN3 publications, and 35 % (18/51) of the nov-related [novH ; ccn 3/nov ; nov/CCN3] publications, it was much easier to consolidate a wide usage of the CCN3 acronym.

Of note, that situation is often encountered in scientific publishing. For example 5 articles used the original FISP-12 acronym, while 5 others used FISP12. On another ground, 1573 articles use IL-33, and 1074 use IL33. This confusion has unexpected consequences. A search with IL-33 does not pull out an article in which CCN3 was reported to physically interact with IL33, therefore suggesting that CCN3 whose expression is regulated by TNFalpha and IL1 cytokines, is a potent player in a variety of inflammatory responses, including neurodegenerative disease, and arthritis. (see Perbal (2006) New insight into CCN3 interactions--nuclear CCN3 : fact or fantasy? Cell Commun Signal. 2006 Aug 8;4:6)

Full references for these articles can be found in Supplementary Data ESM2.

An illustration from the CCN field, is provided by the case of M. Takigawa who switched to the CCN acronym when he realized that the « hcs24 » that he had been using until then would put him aside of the burgeoning CCN field.

« HGNC is responsible for approving unique symbols and names for human loci, including protein coding genes, ncRNA genes and pseudogenes, to allow unambiguous scientific communication » http://www.genenames.org/

See for example the result of a search for CCN5 conducted on the HGNC website (http://www.genenames.org/cgi-bin/search?search_type=all&search=ccn5&submit=Submit) of for CCN2 (http://www.genenames.org/cgi-bin/search?search_type=all&search=ccn5&submit=Submit)

« FibroGen is a research-based biotechnology company using its expertise in connective tissue growth factor (CTGF ) …». A search for CCN2 on the website of the Company leads to a list of reference showing very scarce usage of CCN2)

This type of situation is often encountered in scientific publishing. For example 5 articles used the original FISP-12 acronym, while 5 others used FISP12. On another ground, 1573 articles use IL-33, and 1074 use IL33. This confusion has unexpected consequences. A search with IL-33 does not pull out an article in which CCN3 was reported to physically interact with IL33, therefore suggesting that CCN3 whose expression is regulated by TNFalpha and IL1 cytokines, is a potent player in a variety of inflammatory responses, including neurodegenerative disease, and arthritis. (see Perbal (2006) New insight into CCN3 interactions--nuclear CCN3 : fact or fantasy? Cell Commun Signal. 2006 Aug 8;4:6)

Contributor Information

Annick Perbal, Email: ccnsociety@yahoo.com.

Bernard Perbal, Email: bperbal@gmail.com.

References

- Baxter RC, Binoux MA, Clemmons DR, Conover CA, Drop SL, Holly JM, Mohan S, Oh Y, Rosenfeld RG. Recommendations for nomenclature of the insulin-like growth factor binding protein superfamily. Endocrinology. 1998;139(10):4036. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.10.5083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradham DM, Igarashi A, Potter RL, Grotendorst GR. Connective tissue growth factor: a cysteine-rich mitogen secreted by human vascular endothelial cells is related to the SRC-induced immediate early gene product CEF-10. J Cell Biol. 1991;114(6):1285–1294. doi: 10.1083/jcb.114.6.1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brigstock DR, Goldschmeding R, Katsube KI, Lam SC, Lau LF, Lyons K, Naus C, Perbal B, Riser B, Takigawa M, Yeger H. Proposal for a unified CCN nomenclature. Mol Pathol. 2003;56(2):127–128. doi: 10.1136/mp.56.2.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charrier A, Brigstock DR. Regulation of pancreatic function by connective tissue growth factor (CTGF, CCN2) Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2013;24(1):59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2012.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevalier G, Yeger H, Martinerie C, Laurent M, Alami J, Schofield PN, Perbal B. novH: differential expression in developing kidney and Wilm’s tumors. Am J Pathol. 1998;152(6):1563–1575. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grotendorst GR, Lau LF, Perbal B. CCN proteins are distinct from and should not be considered members of the insulin-like growth factor-binding protein superfamily. Endocrinology. 2000;141(6):2254–2256. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.6.7485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall-Glenn F, Lyons KM. Roles for CCN2 in normal physiological processes. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68(19):3209–3217. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0782-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto Y, Shindo-Okada N, Tani M, Nagamachi Y, Takeuchi K, Shiroishi T, Toma H, Yokota J. Expression of the Elm1 gene, a novel gene of the CCN (connective tissue growth factor, CYR61/Cef10, and neuroblastoma overexpressed gene) family, suppresses in vivo tumor growth and metastasis of K-1735 murine melanoma cells. J Exp Med. 1998;187(3):289–296. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.3.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holbourn KP, Acharya KR, Perbal B. The CCN family of proteins: structure-function relationships. Trends Biochem Sci. 2008;33(10):461–473. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jun J, Lau LF (2011) Taking aim at the extracellular matrix: CCN proteins as emerging therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov 10(12):945–963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Joliot V, Martinerie C, Dambrine G, Plassiart G, Brisac M, Crochet J, Perbal B. Proviral rearrangements and overexpression of a new cellular gene (nov) in myeloblastosis-associated virus type 1-induced nephroblastomas. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12(1):10–21. doi: 10.1128/MCB.12.1.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaki H, Kubota S, Suzuki A, Lazar N, Yamada T, Matsumura T, Ohgawara T, Maeda T, Perbal B, Lyons KM, Takigawa M. Cooperative regulation of chondrocyte differentiation by CCN2 and CCN3 shown by a comprehensive analysis of the CCN family proteins in cartilage. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23(11):1751–1764. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.080615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaassen I, van Geest RJ, Kuiper EJ, van Noorden CJ, Schlingemann RO. The role of CTGF in diabetic retinopathy. Exp Eye Res. 2015;133:37–48. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2014.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latinkic BV, Mercurio S, Bennett B, Hirst EM, Q X, Lau LF, Mohun TJ, Smith JC. Xenopus CYR61 regulates gastrulation movements and modulates wnt signalling. Development. 2003;130(11):2429–2441. doi: 10.1242/dev.00449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau LF. Cell surface receptors for CCN proteins. J Cell Commun Signal. 2016;10(2):121–127. doi: 10.1007/s12079-016-0324-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leask A. CCN2: a novel, specific and valid target for anti-fibrotic drug intervention. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2013;17(9):1067–1071. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2013.812074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leask A. Getting to the heart of the matter: new insights into cardiac fibrosis. Circ Res. 2015;116(7):1269–1276. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.305381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li CL, Coullin P, Bernheim A, Joliot V, Auffray C, Zoroob R, Perbal B. Integration of myeloblastosis associated virus proviral sequences occurs in the vicinity of genes encoding signaling proteins and regulators of cell proliferation. Cell Commun Signal. 2006;4:1. doi: 10.1186/1478-811X-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Ye L, Owen S, Weeks HP, Zhang Z, Jiang WG. Emerging role of CCN family proteins in tumorigenesis and cancer metastasis. Int J Mol Med. 2015;36(6):1451–1463. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2015.2390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason RM. Fell-Muir lecture: connective tissue growth factor (CCN2) -- a pernicious and pleiotropic player in the development of kidney fibrosis. Int J Exp Pathol. 2013;94(1):1–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2613.2012.00845.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCallum L, Irvine AE. (2009) CCN3-a key regulator of the hematopoietic compartment. Blood Rev 23(2):79–85 [DOI] [PubMed]

- O’Brien TP, Yang GP, Sanders L, Lau LF. Expression of CYR61, a growth factor-inducible immediate-early gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10(7):3569–3577. doi: 10.1128/MCB.10.7.3569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennica D, Swanson TA, Welsh JW, Roy MA, Lawrence DA, Lee J, Brush J, Taneyhill LA, Deuel B, Lew M, Watanabe C, Cohen RL, Melhem MF, Finley GG, Quirke P, Goddard AD, Hillan KJ, Gurney AL, Botstein D, Levine AJ. WISP genes are members of the connective tissue growth factor family that are up-regulated in wnt-1-transformed cells and aberrantly expressed in human colon tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(25):14717–14722. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perbal B. Contribution of MAV-1-induced nephroblastoma to the study of genes involved in human Wilms’ tumor development. Crit Rev Oncog. 1994;5:589–613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perbal B. Pathogenic potential of myeloblastosis-associated viruses. Infect Agents Dis. 1995;4(4):212–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perbal B. NOV (nephroblastoma overexpressed) and the CCN family of genes: structural and functional issues. Mol Pathol. 2001;54(2):57–79. doi: 10.1136/mp.54.2.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perbal B (2003) The CCN3 (NOV) cell growth regulator: a new tool for molecular medicine. Expert Rev Mol Diagn 3(5):597–604 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Perbal B. NOV story: the way to CCN3. Cell Commun Signal. 2006;4:3. doi: 10.1186/1478-811X-4-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perbal B. CCN proteins: a centralized communication network. J Cell Commun Signal. 2013;7(3):169–177. doi: 10.1007/s12079-013-0193-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Planque N, Perbal B. A structural approach to the role of CCN (CYR61/CTGF/NOV) proteins in tumourigenesis. Cancer Cell Int. 2003;3(1):15. doi: 10.1186/1475-2867-3-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryseck R-P, Macdonald-Bravo H, Mattéi M-G, Bravo R. Structure, Mappping and expression of fisp12, a growth factor-inducible Gene encoding a secreted cysteine-rich protein. Cell Growth Differ. 1991;2:225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons DL, Levy DB, Yannoni Y, Erikson RL. Identification of a phorbol ester-repressible v-src-inducible gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86(4):1178–1182. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.4.1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffensky M, Mühlenweg A, Wang Z-X, Li S-M, Heide L. Identification of the novobiocin biosynthetic Gene cluster of Streptomyces spheroides NCIB 11891. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44(5):1214–1222. doi: 10.1128/AAC.44.5.1214-1222.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R, Averboukh L, Zhu W, Zhang H, Jo H, Dempsey PJ, Coffey RJ, Pardee AB, Liang P. Identification of rCop-1, a new member of the CCN protein family, as a negative regulator for cell transformation. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18(10):6131–6141. doi: 10.1128/MCB.18.10.6131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, van der Voort D, Shi H, Zhang R, Qing Y, Hiraoka S, Takemoto M, Yokote K, Moxon JV, Norman P, Rittié L, Kuivaniemi H, Atkins GB, Gerson SL, Shi GP, Golledge J, Dong N, Perbal B, Prosdocimo DA, Lin Z. Matricellular protein CCN3 mitigates abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Clin Invest. 2016;126(5):2012. doi: 10.1172/JCI87977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(RTF 993 kb)

(DOCX 48 kb)

(DOCX 43 kb)