Abstract

Different types of dominance hierarchies reflect different social relationships in primates. In this study, we clarified the hierarchy and social relationships in a one-male unit of captive Rhinopithecus bieti observed between August 1998 and March 1999. Mean frequency of agonistic behaviour among adult females was 0.13 interactions per hour. Adult females exhibited a linear hierarchy with a reversal of 10.9%, indicating an unstable relationship; therefore, R. bieti appears to be a relaxed/tolerant species. The lack of a relationship between the agonistic ratio of the adult male towards adult females and their ranks indicated that males did not show increased aggression towards low-ranking females. Differentiated female affiliative relationships were loosely formed in terms of the male, and to some extent influenced by female estrus, implying that relationships between the male and females is influenced by estrus and not rank alone. A positive correlation between the agonistic ratio of adult females and their ranks showed that the degree to which one female negatively impacted others decreased with reduction in rank. Similarly, a positive correlation between the agonistic ratio of females and differences in rank suggests that a female had fewer negative effects on closely ranked individuals than distantly ranked ones. These data indicate that rank may influence relationships between females. A steeper slope of regression between the agonistic ratio and inter-female rank differences indicated that the extent of the power difference in high-ranking females exerting negative effects on low-ranking ones was larger during the mating season than the birth season, suggesting that rank may influence the mating success of females.

Keywords: Dominance style, Hierarchy, Linearity, Rhinopithecus bieti, Social relationship

Social dominance is considered important in studies of animal behaviour, is generally defined in terms of the consistent direction of agonistic behaviour between individuals (Walters & Seyfarth, 1987), and may be measured by asymmetry in repeated interactions (de Waal & Luttrell, 1989). Dominance style, which refers to the way dominants treat subordinates and vice versa (de Waal, 1996), is classified on a continuum with despotic at one end and tolerant/relaxed at the other (Thierry, 2000). In tolerant/relaxed species, high-ranking animals display weak, symmetrical patterns of aggression, more tolerance around resources and reconcile frequently; despotic species show opposite tendencies (Berman et al, 2004). A dichotomy of hierarchies explains dominance relationships in nonhuman primates. A strong dominance hierarchy is characterized by common agonistic1interactions, and less than 5% of reversals indicating stable dominance relationships. By contrast, a weak hierarchy is typified by rare agonistic interactions, and by as much as 15% reversal, suggesting an unstable relationship (Isbell & Young, 2002).

Socio-ecological theory predicts that food resources and predation risk shape the competitive regime and therefore the relationship and dominance structure among group-living female diurnal primates (Sterck et al, 1997; van Schaik, 1989). Scramble competition has been associated with egalitarian dominance relationships, in which hierarchies are unclear and non-linear. Contest competition is linked to despotic dominance relationships, in which hierarchies are clearly established and linear. Such females often formalize dominance relationships, which are expressed in ritualized signals (de Waal, 1989). Contest competition occurs when the distribution of food can accommodate only some individuals and exclude others. Contest competition will increase with the ability to monopolize resources and the number of competitors. A linear hierarchy is adaptive, and reduces the intensity of competition through clear hierarchies when contests are strong (Wittig & Boesch, 2003).

Dominance hierarchies are either poorly defined or not apparent in some colobine species (reviewed by Struhsaker & Leland, 1987). However, in other studies, adult females exhibit a linear hierarchy (Presbytis entellus: Borries et al, 1991; Semnopithecus entellus: Koenig, 2000; Trachypithecus phayrei: Koenig et al, 2004) stable over short periods but fluctuating year to year, and inversely related to female age (Borries et al, 1991). The number of adult females in a group is thought to influence hierarchy linearity indices and reversals as well as dominance relationships. Dominance ranks change more frequently in larger groups than in small and medium-sized groups (Koenig, 2000). Dominance hierarchy is related to size (and therefore age) as well as genealogy in many species of nonhuman primates (see Borries et al, 1991). Moreover, linear dominance hierarchies have been reported amongst one male units (OMUs) in R. roxellana, with ambiguous and reversal interactions at 17.7% (Zhang et al, 2008a). In R. roxellana OMUs, the dominance ranks of females are determined by displacement, and the hierarchy may regulate the strategy of female mating competition since high-ranking females mate more than low-ranging ones (He et al, 2013).

Black-and-white snub-nosed monkeys (Rhinopithecus bieti) travel together as a large and cohesive cohort, predominately as one-male multi-female units (OMUs), but also an all-male unit (AMU) (Kirkpatrick et al, 1998). Adult female R. bieti migrate among OMUs, OMUs sometime split, and merge with individuals from different OMUs (Cui, unpublished data). Relationships among wild colobine females are infrequent and hard to record in comparison to cercopithecidae females (Newton & Dunbar, 1994). The habitat of wild R. bieti is characterized by steep slopes and deep valleys and also because they are shy, it is difficult to habituate them to allow for individual identification. Until now, it has been impossible to obtain systematic data on agonistic interactions between individuals within OMUs for R. bieti in the wild.

Captive R. bieti display a low agonistic interactions rate (0.3 per hour) and reconcile frequently (54.5%). The adult male intervenes frequently and peacefully in conflicts among adult females (Grüter, 2004). According to predictions from socio-ecological models (van Schaik, 1989), a weak or nonlinear hierarchy would be expected in this species. In terms of the dichotomous hierarchy system (Isbell & Young, 2002), the dominance hierarchy of this species would be characterized by frequent reversals, indicating an unstable dominance relationship. Moreover, in OMUs of R. roxellana, adult females can be arranged by dominance rank (He et al, 2013), but they have no tendency to build a strong relationship with each other (Wang et al, 2013). Both male and female immature R. bieti emigrate from natal groups in the wild (Cui, unpublished data), but there is a lack of information on natal dispersal. The overall objective of this study is then to better understand the social structure in snubnosed langurs by analysing dominance hierarchy and affiliative patterns. Specifically, this study aimed to (1) examine dominance style and social relationships in an OMU of R. bieti; (2) explore the role of dominance rank in adult female social relationships; and (3) better understand natal dispersal mechanisms in this species, for example, do females disperse from the natal group and under what conditions? And what is the role played by adult individuals during the dispersal course of their offspring?

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Study animals comprised one adult male and six adult females and their seven offspring housed at the Kunming Institute of Zoology (KIZ) (Kunming, Yunnan, China). Two of the adult females (Fa and Fc) were transferred from Kunming Zoo (KZ) for impregnation on October 12, 1998, and returned after this research. All adults were wild-captured from a band in Weixi county (N27°27′, E 99°11′), northwest Yunnan. The adult male and juveniles≥3 years old were separately housed since the male is often agonistic toward them. This captive group has a similar composition to wild OMUs (Cui et al, 2008). Age-sex composition and the matrilines of these individuals appear in Cui & Xiao (2004).

Enclosure environment

Study subjects were kept in an enclosure that contained an indoor room (5.2 m long, 2.0 m wide and 2.7 m high) and an outdoor octahedronal cage (66 m2×4 m). The enclosure is evenly divided into two sections. A cement wall separated the indoor room, and the wire mesh fence divided the outdoor pen, which was surrounded by 8 cm-interval vertical metal bars. There was a basin full of water in each cage. Animals on each side could see each other through the metallic mesh, and the observer could also see the animals clearly through the metal fence. A keeper fed the monkeys plants (e.g., privet, cherry, willow leaves), some fruit (apple, banana, pear, tomato) and nutritionally balanced artificial food at 0900h, 1200h and 1600h each day. The plants and fruit were dispersed at two sites in each part of the cage to avoid food competition among animals; artificial food was allocated based on body-size for each animal.

Data collection

Linearity relies on the number of established binary dominance relationships and on the degree of transitivity in these relationships (Appleby, 1983; de Vries, 1995). It should be adaptive for a linear hierarchy when contest competition is strong and where the strength of aggression needs to be reduced by clear dominance relationships among competitors (de Vries et al, 2006). Data on affiliative and agonistic behaviours of all individuals in two cages were collected from August 20, 1998 to March 10, 1999. All animals were observed for 7-8 hours per day, and 2-3 days per week. Total observations were 364 hours, with 243 hours in the mating season and 121 hours in the birth season. Affiliative interactions, recorded by focal-animal scan sampling (every 5 minutes) (Altmann, 1974), are comprised of proximity (being within one meter, but not in contact) and contact (all body contact except agonism and playing). All dyadic interactions with the actor and receiver were recorded using all occurrences sampling (Altmann, 1974) during the period between scanning points. Dyadic interactions include dominant and submissive behaviours. Dominant behaviour is defined as one of the following performed by the initiator: threat, lunge, slap and chase. Submissive behaviour includes responses by the recipient: cower, displace, flee and scream. Animals were names as the following rules: Mk repressents the male adult; female adults are named as Fx (x represents different individuals); immatures are named as age and mother’ s identity, e.g., Ib is the infant of Fb. This research complied with protocols approved by the Animal Care Committee of Yunnan Province and adhered to Chinese National Laws on Protection of Wild Animals.

Data analysis

It has been reported that wild adult R. rexallana females in OMUs change dominance ranks between the mating and birth seasons (Li et al, 2006), thus dominance relationships were analysed in two periods in this study: from August 20 to December 31, 1998, and from January 1 to March 10, 1999. The first period took place primarily in the mating season (MS), and the second period was within the birth season (BS). A combined dominance matrix was constructed for the whole study period due to the absence of agonistic behaviour between some adults and juveniles either in MS or BS. We analysed the frequency of agonistic interactions (n per individual observation hour).

Dominance ranking of individuals was measured using David’s score (Gammell et al, 2003). Six or more individuals were required to test the linearity of dominance hierarchy, thus the linearity of hierarchy among seven adults in this study was measured using Kendall’s coefficient K (Appleby, 1983). To describe the extent to which agonistic interactions were asymmetric within dyads, the directional inconsistency index (DII) was calculated as the percentage of all agonism directed to the less frequent direction within dyads (de Waal, 1977). The term “reversal” refers to those episodes below the diagonal of a matrix, and is usually expressed as the percentage of the total number of interactions (e.g., Isbell & Pruetz, 1998). The procedure for calculating the rank of individuals on an interval scale followed Singh et al (2003).

The agonistic ratio for each individual was calculated in terms of the equation: [n (agonistic interactions won+1)]/[n (agonistic interactions lost)+1]](NewtonFisher, 2004). To test for differences across seasons, we compared slopes of two linear regressions between agonistic ratios of adult females and their ordinal dominance ranking, and between agonistic ratios of females and their rank difference (Zar, 1999). Spearman rank correlation tests (Rs) were used to examine the relationship between dominance ranks of adult females and age. Multiple linear regression tests were used to check the relationship between immature rank and age, between the agonistic ratio of the adult male to adult females and their ranks, and between the agonistic ratio of females and rank distance. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to examine differences in the agonistic ratio of the adult male to adult females between the two seasons. The Wilcoxon Matched Pairs Test was used to investigate differences in agonistic frequencies of adult females between both seasons. The relationship between parents and their offspring was tested using One-way ANOVA and t-tests. The index of similarity can be calculated using the method of clustering (Lehner, 1979). A single-link cluster analysis dendrogram was constructed for affiliative similarities. All tests were two-tailed and significance was set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Dominance hierarchy

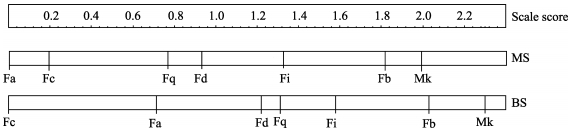

The dominance matrix was constructed from 717 agonistic interactions and revealed a linear hierarchy among adults in the mating season (Kendall’s coefficient: K=1, P=0.002) (Table 1) and a reversal of 10.7% indicating an unstable relationship. Similarly, there was also a linear hierarchy among adults in the birth season (K=1, P < 0.01), and the reversal of 9.3% suggested an unstable relationship (Table 2). David’s score indicated that the adult male was dominant to adult females, and adult females to immature animals. Interval scales of female ranks changed with season (Figure 1). Two pairs of adult females (Fd vs. Fq, and Fa vs. Fc) changed rank across seasons, but others consistently occupied higher positions in both seasons (Table 1, Table 2). The ranks of adult females were not correlated with age in either season (Rs < 0.09, n=6, P > 0.05 for both).

Table 1.

Frequencies of agonistic interactions among adults during the mating period based on dominance matrix

| Actor | Recipient | ∑ | DS | ||||||

| Mk | Fb | Fi | Fd | Fq | Fc | Fa | |||

| Mk | - | 20 | 9 | 25 | 19 | 70 | 25 | 168 | 15.6 |

| Fb | 5 | - | 2 | 1 | 18 | 46 | 14 | 86 | 13.9 |

| Fia | 3 | - | 3 | 21 | 85 | 47 | 159 | 4.9 | |

| Fda | 5 | 1 | - | 9 | 67 | 93 | 175 | -0.6 | |

| Fqa | 3 | 2 | 7 | 5 | - | 20 | 16 | 53 | -5.2 |

| Fca | 1 | 8 | 7 | - | 30 | 46 | -13.9 | ||

| Fa | 2 | 8 | 3 | 17 | - | 30 | -16.6 | ||

| ∑ | 17 | 22 | 21 | 50 | 77 | 305 | 225 | 717 | |

| aIndividuals were estrous in the mating season, estimated by mating activities, and further corroborated by newborns in 1999. The descending order for onset of female estrus is as follows: Fi>Fq>Fd>Fc, in which Fc was in estrus before being transferred from Kunming Zoo. DS: David’s score; Mk: Male adult; Fx: Female adults (x represents different individuals). | |||||||||

Table 2.

Frequencies of agonistic interactions for adults during the birth period

| Actor | Recipient | ∑ | DS | ||||||

| Mk | Fb | Fi | Fq | Fd | Fa | Fc | |||

| Mk | - | 7 | 5 | 9 | 9 | 5 | 44 | 79 | 16.3 |

| Fb | - | 1 | 9 | 1 | 8 | 22 | 41 | 12.6 | |

| Fi | 1 | - | 27 | 5 | 30 | 38 | 101 | 4.9 | |

| Fq | 4 | 2 | 8 | - | 2 | 6 | 10 | 32 | -0.6 |

| Fd | 2 | 1 | 1 | - | 2 | 20 | 26 | -2.3 | |

| Fa | 2 | 5 | - | 12 | 19 | -11.5 | |||

| Fc | 2 | - | 2 | -20.1 | |||||

| ∑ | 7 | 9 | 17 | 51 | 17 | 53 | 146 | 300 | |

| DS: David’s score; Mk: Male adult; Fx: Female adults (x represents different individuals). | |||||||||

Figure 1.

Dominance rank of adult individuals on an interval scale in the mating season (MS) and birth season (BS)

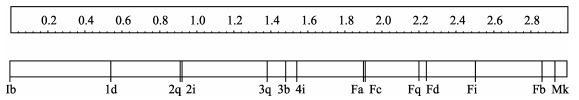

There was a significant linear hierarchy of adults in the whole period (K=1, P < 0.01), with a reversal of 10.3%, thus implying an unstable relationship (Table 3). The interval scale of ranks for all monkeys is displayed in Figure 2. Immature ranks were correlated with age (R2=0.96, F1, 5=123.2, P < 0.001).

Table 3.

Frequencies of agonistic interactions for all individuals over the whole study period

| Actor | Recipient | ∑ | DS | |||||||||||||

| Mk | Fb | Fi | Fd | Fq | Fc | Fa | 4i | 3b | 3q | 2i | 2q | 1d | Ib | |||

| Mk | - | 27 | 14 | 34 | 28 | 114 | 30 | 864 | 444 | 249 | 36 | 22 | 3 | 0 | 1865 | 80.4 |

| Fb | 5 | - | 3 | 2 | 27 | 68 | 22 | 8 | 14 | 21 | 65 | 47 | 7 | 52 | 341 | 73.5 |

| Fi | 4 | - | 8 | 48 | 123 | 77 | 6 | 70 | 49 | 21 | 90 | 40 | 8 | 544 | 57.3 | |

| Fd | 7 | 2 | - | 10 | 87 | 95 | 10 | 24 | 40 | 198 | 72 | 57 | 7 | 609 | 41.2 | |

| Fq | 7 | 4 | 15 | 7 | - | 30 | 22 | 96 | 200 | 62 | 245 | 140 | 89 | 21 | 938 | 38.3 |

| Fc | 1 | 8 | 7 | - | 32 | 173 | 330 | 402 | 162 | 96 | 63 | 7 | 1281 | 17.0 | ||

| Fa | 4 | 8 | 8 | 29 | - | 104 | 273 | 243 | 164 | 118 | 8 | 1 | 960 | 16.8 | ||

| 4i | 1 | 1 | 12 | 2 | 8 | - | 162 | 252 | 33 | 49 | 12 | 13 | 545 | -12.5 | ||

| 3b | 5 | 5 | 35 | 7 | 13 | 65 | - | 163 | 22 | 20 | 2 | 4 | 341 | -16.4 | ||

| 3q | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 12 | 102 | 75 | - | 36 | 45 | 6 | 5 | 297 | -23.4 | ||

| 2i | 6 | 1 | 3 | - | 10 | 24 | 6 | 50 | -55.3 | |||||||

| 2q | 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 5 | - | 15 | 12 | 41 | -55.4 | ||||||

| 1y | 2 | 2 | 2 | - | 6 | 12 | -73.6 | |||||||||

| Ib | 1 | - | 1 | -101.3 | ||||||||||||

| ∑ | 24 | 36 | 47 | 77 | 181 | 468 | 311 | 1433 | 1594 | 1487 | 990 | 709 | 326 | 142 | 7825 | |

| DS: David’s score; Mk: Male adult; Fx: Female adults (x represents different individuals); Immatures are named as ages and mother’s identity ( e.g., Ib: the infant of Fb). | ||||||||||||||||

Figure 2.

Rank of all individuals on an interval scale during the whole study period

Relationships between the adult male and adult females

The overall mean frequency of agonistic behaviour between the male and females was 0.12 interactions per hour (MS: 0.13 vs. BS: 0.12). The agonistic ratio of the male towards females did not differ between seasons (MS: 12.2 vs. BS: 13.3, K-S test: Z=1.16, P=0.14). No relationship was found between the agonistic ratio and female ordinal ranking for both seasons (MS: R2=0.63, F1, 4=6.81, P=0.059; BS: R2=0.39, F1, 4=2.57, P=0.18).

Relationships among adult females

There was a significant linear hierarchy among females in each season (K=1, P=0.022 for both) with a reversal of 9.2% in MS and 8.1% in BS. In the social unit, females were tolerant of each other. The overall mean frequency of agonistic behavior among females was 0.13 interactions per hour over the whole study period. No difference was found in inter-female agonistic rates between seasons (MS: 0.15 vs. BS: 0.12 interactions per hour, Wilcoxon matched pairs test: Z=0.45, P=0.65). There was a positive correlation between the agonistic ratio of each female and its ordinal ranking in both seasons (R2>0.73, F1, 4>11.62, P < 0.05 for both), and no difference was found in slopes from linear regressions between two seasons (t=1.47, t0.05 (1), 8=1.86, P > 0.05). A positive correlation was found between the agonistic ratio of females and ordinal rank differences in both seasons (R2>0.85, F1, 3>18.5, P < 0.05 for both), and the slope of the linear regression was significantly larger in MS than in BS (t=7.70, t0.001 (2), 6=5.96, P < 0.001).

Bi-directionality of aggression

The DII suggested that aggression was primarily unidirectional. A total of 105 interactions were directed in the less common direction within dyads (DII=10.3%), in which DII was 10.7% in MS and 9.3% in BS. DIIs (8.1%-11.3%) were consistent in each period and across each partner (Table 4).

Table 4.

Directional inconsistency index of agonistic interactions among adult monkeys during the study period

| 20/08/98-31/12/98 | 01/01/99-10/03/99 | 20/08/98-10/03/99 | |

| All partner combination | 77/717 (10.7%) | 28/300 (9.3%) | 105/1017 (10.3%) |

| Male-female dyads | 17/185 (9.2%) | 7/86 (8.1%) | 24/271 (8.9%) |

| Female-female dyads | 60/532 (11.3%) | 21/214 (9.8%) | 81/746 (10.9%) |

Relationships between parents and offspring

The agonistic frequency for father-to-offspring correlated positively with offspring age (R2=0.84, F1, 3=15.32, P=0.03), but not for immature animals less than 2 years old (LSD: P > 0.05 for both). In contrast, the agonistic frequency for mother-to-offspring did not correlate with offspring age (R2=0.17, F1, 3=0.68, P=0.48) and shifted with age (F1, 341=35.98, P < 0.001): mothers displayed aggression towards 2-year-old offspring more frequently than 1-year-old animals (LSD: P < 0.01), and 3-year-old offspring more than 4-year-old animals (LSD: P < 0.05).

The father did not direct more agonisms towards his infants than mothers did (0.01 vs. 0.03 times/h, t253=1.70, P=0.09). Mothers directed more agonisms towards their 2-year-old offspring than the father did (0.20 vs. 0.11 times/h, t243=2.30, P=0.02), but the father directed more agonisms towards≥3-year-old offspring than mothers did (0.94 vs. 0. 27 times/hour, t187=4.40, P < 0.001 for 3- year-old; 2.33 vs. 0.06 times/hour, t85=2.04, P=0.045 for 4-year-old). Moreover, the father directed more agonisms towards his offspring during MS than BS (0.90 vs 0.32 times/h, t428=2.71, P=0.007), particularly towards≥3-year-old offspring (3-year-old: t144=3.24, P=0.0015; 4-year-old: t71=2.27, P=0.026); this was not true for mothers (0.11 vs 0.17 times/hour, t346=1.66, P=0.10).

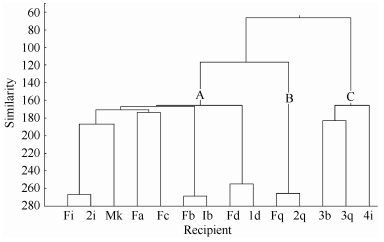

Affiliative interactions

There were three clusters in the OMU (Figure 3). Three nursing mothers, the adult male and two adult females from KZ formed a loose association in cluster A. Cluster B was comprised of one adult female and her offspring. Three juveniles formed cluster C. The strongest social bond appeared in one mother-infant pair at the 268 level of affiliative similarity, and the next were two mother-2-year-old-juvenile and one motheryearling pairs at the 255 level of similarity. Affiliative bonds among females were clearly differentiated. Adult females (Fa and Fc) with the lowest ranks in the adult class tended to stay together, and associate with the adult male through the adult female Fi. Because mothers followed their yearlings around, offspring less than two years of age were seldom left alone. They were also often found near their tolerant father. An adult female (Fd) with a crippled left leg was unable to follow her yearlings, and this may have resulted in a smaller level of similarity. The three > 2--year-old juveniles were more isolated than the≤2-year-old ones because their father directed more agonism towards them.

Figure 3.

Dendrogram based on affiliation among members of a captive Rhinopithecus bieti OMU

DISCUSSION

Dominance hierarchy

Adult female R. bieti displayed an average of 0.13 interactions per hour and this rate is at the low end when compared with other colobines (1.20 for P. thomasi: Sterck & Steenbeek, 1997; 0.6 for C. polykomos, 0.19 for Procolobus badius; Korstjens et al, 2002; 0.25 for T. phayrei: Koenig et al, 2004; and 0.22 displacement rate per hour for R. roxellana: He et al, 2013). A previous study of captive R. bieti, consisting of three adults, one sub-adult and five immatures, reported an overall mean frequency of agonistic interactions per hour of 0.30 for individuals over one year of age (Grüter, 2004). This inconsistency in agonistic rate may be the result of two possibilities. First, we did not collect data on agonisms during feeding. Second, it might relate to differences in the age-sex composition of subjects between the two studies. In our study, 87% of agonisms were made by immature animals, thus the higher rate might result from the higher proportion of immatures (67%) in the previous study. R. bieti feed mainly on evenly distributed lichens in its northern range (Kirkpatrick et al, 1998), but their primary foods, such as deciduous broadleaves (Ding & Zhao, 2004) and bamboo leaves (Yang & Zhao, 2001), are patchily distributed in its southern range. If food competition plays an important role in inter-female interactions, the agonistic rate may be higher in its northern range than southern range; however, further research is needed to clarify this.

Agonistic behaviour might be more common in captive than wild animals, but appears to follow a linear hierarchy in guenons (Cercopithecus diana, C. solatus, C. mitis) and patas monkeys (Erythrocebus patas) in both captivity and the wild (see Lemasson et al, 2006). We found a linear dominance hierarchy among adult females in our R. bieti, as has been reported in other colobines (Borries et al, 1991; Koenig, 2000; Koenig et al, 2004) and in patas monkeys (Isbell & Pruetz, 1998). Consequently, our study does not support the idea that lower agonistic rates coincide with an indiscernible hierarchy (Isbell & Young, 2002). The consensus is that the dominance hierarchy between females in groupliving primates relates to factors such as resource competition and kinship. The linear hierarchy of female R. bieti outside of feeding contexts may reflect scramble competition among females in the wild. Here, the adult male was dominant to adult females and adult females to immatures, consistent with reports from wild R. roxellana (Li et al, 2006). Dominance ranks of adult female R. bieti are not based on age, in contrast to other colobines (Borries et al, 1991; Koenig et al, 2004). Colobine daughters do not acquire ranks similar to those of their mothers, unlike in most cercopithecines (Melnick & Pearl, 1987). Juvenile hanuman langur females rise in rank above older and even larger females (Borries et al, 1991). During this study, however, all juvenile females may have been too young (3-4 years) to enter higher rank, and were subordinate to adult females. These young females may begin to rise in rank at an age of five or even six years, if they rise in rank as in hanuman langurs (Borries et al, 1991; Koenig, 2000).

Hierarchy style

A previous study of M. thibetana provided quantitative indices to identify dominance style of a species (Berman et al, 2004). The DII of a typically despotic species ranges from 0.7% to 4.1%, and one value of 9.0% is available for a relaxed species. The conciliatory tendency ranges from 5% to 15% for despotic species, and from 35% to 48% for relaxed species. Notably, comparable values are for all adults were combined together (Berman et al, 2004). In our study, the DII of 10.3% is larger than 9.0%, thus within the range of DIIs for relaxed species. The dominance style hypothesis predicts that a more relaxed style is correlated with high levels of post-conflict reconciliation (de Waal & Luttrell, 1989). The conciliatory tendency is 54.5% for captive R. bieti monkeys over 1-year-old age (Grüter, 2004), 51.3% for all captive adult spectacled leaf monkeys (Arnold & Barton, 2001), and 40% for captive R. roxellana (Ren et al, 1991). Moreover, bidirectional aggression of captive R. bieti is common (28% of all conflicts) (Grüter, 2004), and many wild R. bieti usually forage in one tree with rare agonisms (kirkpatrick et al, 1998). therefore, R. bieti is likely a relaxed or tolerant species.

Relationships between the male and adult females

The similar agonistic ratio of the adult male towards adult female R. bieti showed that the male directed unbiased agonisms towards females in MS and BS. Moreover, the lack of correlation between agonistic ratios of the male towards females and rank suggests that the male did not direct more agonism towards lowranking females than high-ranking ones. Therefore, dominance rank appears to not play a role in maintaining the relationship between the adult male and adult females in OMUs, that is, the adult male does not sustain relationships with adult females in terms of their dominance rank.

Inter-female relationships in OMUs

Dominance gradient, rather than linearity, is considered the key element of a hierarchy because it dictates the degree to which one female can exert a negative effect on another (Henzi & Barrett, 1999). A steep gradient increases the extent of power differential between high- and low-ranking females, allowing the former to exert a strong negative influence on the latter (Barrett et al, 2002). The positive correlation between the agonistic ratio of adult females and their rank indicates that the degree to which one female influences others declined with a decrease in their rank. A similar positive correlation between the agonistic ratio of adult females and their rank differential indicates that they directed less negative behaviour to closely ranked females than distantly ranked one. These patterns mean that dominance rank should play an important role in relationships among adult females in the OMU of R. bieti. A steeper gradient in MS implied a strong power of high-ranking females to exert negative effects on low-ranking ones as compared with that in BS, which implies that dominance rank may affect the mating success of females, as in R. roxellana (He et al, 2013).

Relationships between parents and offspring

Extra-group males are common in many colobines, which typically show male-biased dispersal (Newton & Dunbar, 1994), but extra-group females do occur in some species (P. senex: Rudran, 1973; R. roxellana: Zhang et al, 2008b) and at times in N. larvatus, T. auratus, T johnii and P. thomasi (Yeager & Kool, 2000). Young males in some primate species encounter increased rates of aggression from resident adult males, which has been assumed to be the cause of their eventual emigration (Struhsaker & Leland, 1987). However, male lowe’s guenons living in one-male groups emigrate voluntarily if their father is still present in the group when they mature (Bourlière et al, 1970). Nulliparous females may disperse for inbreeding avoidance when they mature and their father still has a breeding status (Clutton-Brock, 1989). In our study, continual agonisms of a father towards older offspring of both sexes suggest they must emigrate from their natal group and their father. The intensity of agonism of the father towards his offspring escalated with age, but this was not true for mothers, suggesting that natal dispersal of immature animals is caused by their father rather than their mother, at least when the father still resides in the group. If an adult male enters a bisexual group and drives out the previous breeding male, individuals are presumably expelled by males that are not their fathers (Pusey & Packer, 1987).

Female R. bieti become mature at 4.5 years of age, and males at about 6.5-7.0 years of age (Zou, 2002). The father directed agonisms towards his≥3-year-old offspring more frequently than < 3-year-old ones, suggesting that individuals of both sexes begin emigration at puberty (Pusey & Packer, 1987). In addition, the father evicted his≥3-year-old of offspring more frequently in MS than BS, and accordingly we predict that natal dispersal occurs before or during MS.

Mothers directed agonisms towards 2-year-old offspring more frequently than 1-year-old ones because mothers began weaning their offspring at 1.5 years of age. In wild-provisioned and captive populations of hanuman langurs, infants are weaned at an age of 12.8 months. However, for wild langurs at Ramnagar, infants were on average weaned at an age of two years. This difference in weaning age is related to nutritional conditions between two different living environments (Koenig & Borries, 2001).

Affiliative relations in the OMU

The breeding male has the strongest social association with the first estrus female (Fi), then unfamiliar females (Fa and Fc), and then other females of decreasing rank. This suggests that social bonds between adults of both sexes are first affected by female estrus, and then by their rank. Conversely, R. roxellana females have no strong tendency to build a relationship with the adult male in OMUs in the wild (Wang et al, 2013). The female affiliative relationship is differentiated, and weakly formed on the basis of the breeding male, and also influenced by their rank. Future research is needed to confirm the pattern among adults of OMUs in the wild. On the other hand, the strongest social association occurs in mother-infant pairs in the OMU of R. bieti. Affiliation between the mother and offspring is weaker as they grow, implying that immature animals gradually socialize and become independent. In most polygynous species, males provide little paternal care (Pusey & Packer, 1987). In this study, the observed adult male R. bieti provided little direct paternal care to infants, but was tolerant of their staying and playing in/around him, and occasionally sniffed them.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Special thanks to Prof. R.-J. ZOU at Kunming Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences for support; Mr. Y.-Z. LU (animal keeper) for his assistance during data-collection; and to three anonymous reviewers for valuable suggestions.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31160422, 30960084), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2013M542379), the Program for New Century Excellent Talents in University (NCET-12-1079), and the Key Subject of Wildlife Conservation and Utilization in Yunnan Province.

REFERENCES

- 1. Altmann J. 1974. Observational study of behavior: sampling methods. Behaviour, 49 (3): 227- 266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Appleby MC. 1983. The probability of linearity in hierarchies. Animal Behaviour, 31 (2): 600- 608. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Arnold K, Barton RA. 2001. Postconflict behavior of spectacled leaf monkeys (Trachypithecus obscurus). I. Reconciliation.. International Journal of Primatology, 22 (2): 243- 266. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barrett L, Gaynor D, Henzi SP. 2002. A dynamic interaction between aggression and grooming reciprocity among female chacma baboons. Animal Behaviour, 63 (6): 1047- 1053. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Berman CM, Ionica CS, Li JH. 2004. Dominance style among Macaca thibetana on Mt. Huangshan, China. International Journal of Primatology, 25 (6): 1283- 1312. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Borries C, Sommer V, Srivastava A. 1991. Dominance, age, and reproductive success in free-ranging female Hanuman langurs (Presbytis entellus). International Journal of Primatology, 12 (3): 231- 257. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bourlière F, Hunkeler C, Bertrand M. 1970. Ecology and behaviour of lowe’s guenon (Cercopithecus campbelli lowei) in the Ivory Coast. In: Napier JR, Napier PH. Old World Monkeys. New York: Academic Press; 279- 350. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Clutton-Brock TH. 1989. Female transfer and inbreeding avoidance in social mammals. Nature, 337 (6202): 70- 72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cui LW, Xiao W. 2004. Sexual behavior in a one-male unit of Rhinopithecus bieti in captivity. Zoo Biology, 23 (6): 545- 550. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cui LW, Huo S, Zhong T, Xiang ZF, Xiao W, Quan RC. 2008. Social organization of black-and-white snub-nosed monkeys (Rhinopithecus bieti) at Deqin, China. American Journal of Primatology, 70 (2): 169- 174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. de Vries H. 1995. An improved test of linearity in dominance hierarchies containing unknown or tied relationships. Animal Behaviour, 50 (5): 1375- 1389. [Google Scholar]

- 12. de Vries H, Stevens JMG, Vervaecke H. 2006. Measuring and testing the steepness of dominance hierarchies. Animal Behaviour, 71 (3): 585- 592. [Google Scholar]

- 13. de Waal FBM. 1977. The organization of agonistic relations within two captive groups of Java-monkeys (Macaca fascicularis). Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie, 44 (3): 225- 282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. de Waal FBM. 1989. Dominance “style” and primate social organisation. In: Staden V, Foley RA. Comparative Socioecology. Oxford: Blackwell; 243- 263. [Google Scholar]

- 15. de Waal FBM. 1996. Conflict as negotiation. In: McGrew WC, Marchant LF, Nishida T. Great ape Societies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 159- 172. [Google Scholar]

- 16. deWaal FBM, Luttrell LM. 1989. Toward a comparative socioecology of the genus Macaca: different dominance styles in rhesus and stumptail monkeys. American Journal of Primatology, 19 (2): 83- 109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ding W, Zhao QK. 2004. Rhinopithecus bieti at Tacheng, Yunnan: Diet and Daytime activities. International Journal of Primatology, 25 (3): 583- 598. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gammell MP, De Vries H, Jennings DJ, Carlin CM, Hayden TJ. 2003. David’s score: a more appropriate dominance ranking method than Clutton-Brock et al. ’s index. Animal Behaviour, 66 (3): 601- 605. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Grüter CC. 2004. Conflict and postconflict behaviour in captive blackand-white snub-nosed monkeys (Rhinopithecus bieti). Primates, 45 (3): 197- 200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. He HX, Zhao HT, Qi XG, Wang XW, Guo ST, Ji WH, Wang CL, Wei W, Li BG. 2013. Dominance rank of adult females and mating competition in Sichuan snub-nosed monkeys (Rhinopithecus roxellana) in the Qinling Mountains, China. Chinese Science Bulletin, 58 (18): 2205- 2211. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Henzi SP, Barrett L. 1999. The value of grooming to female primates. Primates, 40 (1): 47- 59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Isbell LA, Pruetz JD. 1998. Differences between vervets (Cercopithecus aethiops) and patas monkeys (Erythrocebus patas) in agonistic interactions between adult females. International Journal of Primatology, 19 (5): 837- 855. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Isbell LA, Young TP. 2002. Ecological models of female social relationships in primates: similarities, disparities, and some directions for future clarity. Behaviour, 139 (2): 177- 202. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kirkpatrick RC, Long YC, Zhong T, Xiao L. 1998. Social organization and range use in the Yunnan snub-nosed monkey Rhinopithecus bieti. International Journal of Primatology, 19 (1): 13- 51. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Koenig A. 2000. Competitive regimes in forest-dwelling hanuman langur females (Semnopithecus entellus). Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 48 (2): 93- 109. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Koenig A, Borries C. 2001. Socioecology of hanuman langurs: the story of their success. Evolutionary Anthropology, 10 (4): 122- 137. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Koenig A, Larney E, Lu A, Borries C. 2004. Agonistic behavior and dominance relationships in female Phayre’s leaf monkeys-preliminary results. American Journal of Primatology, 64 (3): 351- 357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Korstjens AH, Sterck EHM, Noë R. 2002. How adaptive or phylogenetically inert is primate social behaviour? A test with two sympatric colobines. Behaviour, 139 (2): 203- 225. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lehner PN. 1979. Handbook of Ethological Methods. New York: Garland STPM Press. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lemasson A, Blois-Heulin C, Jubin R, Hausberger M. 2006. Female social relationships in a captive group of Campbell’s Monkeys (Cercopithecus campbelli campbelli). American Journal of Primatology, 68 (12): 1161- 1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Li BG, Li HQ, Zhao DP, Zhang YH, Qi XG. 2006. Study on dominance hierarchy of the Sichuan snub-nosed monkey (Rhinopithecus roxellana) in Qinling Mountains. Acta Theriologica Sinica, 26 (1): 18- 25. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Melnick DJ, Pearl MC. 1987. Cercopithecines in multi-male groups: genetic diversity and population structure. In: Smuts BB, Cheney DL, Seyfarth RM, Wrangham RW, Struhsaker TT. Primate Societies. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 123- 134. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Newton PN, Dunbar RIM. 1994. Colobine monkey society. In: Davies AG, Oates JF. Colobine Monkeys: Their Ecology, Behaviour and Evolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 311- 346. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Newton-Fisher NE. 2004. Hierarchy and social status in Budongo chimpanzees. Primates, 45 (2): 81- 87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pusey AE, Packer C. 1987. Dispersal and philopatry. In: Smuts BB, Cheney DL, Seyfarth RM, Wrangham RW, Struhsaker TT. Primate Societies. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 250- 266. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ren RM, Yan KH, Su YJ, Qi JF, Liang B, Bao WY, de Waal FBM. 1991. The reconciliation behavior of golden monkeys (Rhinopithecus roxellanae roxellanae) in small breeding groups. Primates, 32 (3): 321- 327. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rudran R. 1973. Adult male replacement in one-male troops of purplefaced langurs (Presbytis senex senex) and its effect on population structure. Folia Primatologica, 19 (2): 166- 192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Singh M, Singh M, Sharma AK, Krishna BA. 2003. Methodological considerations in measurement of dominance in primates. Current Science, 84 (5): 709- 713. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sterck EHM, Steenbeek R. 1997. Female dominance relationships and food competition in the sympatric Thomas langur and long-tailed macaque. Behaviour, 134 (9/10): 749- 774. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sterck EHM, Watts DP, van Schaik CP. 1997. The evolution of female social relationships in nonhuman primates. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 41 (5): 291- 309. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Struhsaker TT, Leland L. 1987. Colobines: infanticide by adult males. In: Smuts BB, Cheney DL, Seyfarth RM, Wrangham RW, Struhsaker TT. Primate Societies. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Thierry B. 2000. Covariation of conflict management patterns in macaque societies. In: Aureli F, de Waal FBM. Natural Conflict Resolution. Berkeley: University of California Press; 106- 128. [Google Scholar]

- 43. van Schaik CP. 1989. The ecology of social relationships among female primates. In: Standen V, Foley RA. Comparative Socioecology: the Behavioural Ecology of Humans and Other Mammals. Oxford: Blackwell; 195- 218. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Walters JR, Seyfarth RM. 1987. Conflict and cooperation. In: Smuts BB, Cheney DL, Seyfarth RM, Wrangham RW, Struhsaker TT. Primate Societies. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 306- 317. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wang XW, Wang CL, Qi XG, Guo ST, Zhao HT, Li BG. 2013. A newly-found pattern of social relationships among adults within one-male units of golden snub-nosed monkeys (Rhinopithecus roxenalla) in the Qinling Mountains, China. Current Zoology, 8 (4): 400- 409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wittig RM, Boesch C. 2003. Food competition and linear dominance hierarchy among female chimpanzees of the Tai National Park. International Journal of Primatology, 24 (4): 847- 867. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Yang SJ, Zhao QK. 2001. Bamboo leaf-based diet of Rhinopithecus bieti at Lijiang, China. Folia Primatology, 72 (2): 92- 95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Yeager CP, Kool K. 2000. The behavioral ecology of Asain colobines. In: Whitehead PF, Jolly CJ. Old World Monkeys. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 496- 521. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zar JH. 1999. Biostatistical Analysis. 4th ed. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Zhang P, Watanabe K, Li BG, Qi XG. 2008. a. Dominance relationships among one-male units in a provisioned free-ranging band of the Sichuan snub-nosed monkeys (Rhinopithecus roxellana) in the Qinling Mountains, China. American Journal of Primatology, 70 (7): 634- 641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Zhang P, Watanabe K, Li BG. 2008. b. Female social dynamics in a provisioned free-ranging band of the Sichuan snub-nosed monkey (Rhinopithecus roxellana) in the Qinling Mountains, China. American Journal of Primatology, 70 (11): 1013- 1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Zou RJ. 2002. Domestication, reproduction and management of Rhinopithecus bieti. In: Quan GQ, Xie JY. Research on the Golden Monkeys. Shanghai: Shanghai Science and Education Press; 417- 444. [Google Scholar]