Abstract

Glaucoma is a common optic neuropathy that can lead to irreversible vision loss, and intraocular pressure (IOP) is the only known modifiable risk factor. The primary method of treating glaucoma involves lowering IOP using medications, laser and/or invasive surgery. Currently, we rely on in-office measurements of IOP to assess diurnal variation and to define successful management of disease. These measurements only convey a fraction of a patient’s circadian IOP pattern and may frequently miss peak IOP levels. There is an unmet need for a reliable and accurate device for 24-h IOP monitoring. The 24-h IOP monitoring devices that are currently available and in development fall into three main categories: self-monitoring, temporary continuous monitoring, and permanent continuous monitoring. This article is a systematic review of current and future technologies for measuring IOP over a 24-h period.

Keywords: 24-h, Contact lens sensor, EYECARE® (Implandata Ophthalmic Products GmbH), Glaucoma, Icare® tonometer (Icare Finland Oy), Intraocular pressure, Phosphene tonometer, Self-tonometry, Triggerfish® (Sensimed AG), Wireless intraocular transducer

Introduction

Glaucoma is a leading cause of irreversible blindness with a global impact that is estimated to include 60.5 million patients [1, 2]. To date, intraocular pressure (IOP) is the only modifiable risk factor. Treatment decisions are based on in-office measurements of IOP to assess diurnal variation and to define successful management of disease; however, these measurements only convey a fraction of a patient’s circadian IOP pattern. It has been well documented that patients can demonstrate a wide variability in IOP throughout a 24-h period due to activity, nocturnal elevation, physiologic body position (supine vs. erect), and individual variability of response to topical medications [3, 4].

Several studies have emphasized the clinical relevance of 24-h IOP monitoring, which have revealed that higher peak IOPs and a wider range of IOP fluctuations correlate with confirmed progression. In a retrospective study, 29 patients with primary open angle glaucoma (POAG) and normal tension glaucoma (NTG) underwent 24-h IOP monitoring in a hospital sleep laboratory. These patients were known to have confirmed progression based on perimetry despite “well-controlled” IOP measurements during clinic visits. Their 24-h IOP curve was compared to their previously measured clinic-based IOP curve while maintaining their current glaucoma medication regimen. The mean IOP value was similar between the two groups; however, the peak 24-h IOP was 4.9 mmHg higher than the clinic-based diurnal curve (p < 0.0001). In addition, the 24-h IOP curve for four patients demonstrated at least a 12 mmHg increase in peak IOP. Approximately 51.7% of patients recorded their peak IOP outside standard office hours, although no specific aggregate pattern was revealed [5].

Similarly, another retrospective study reviewed the 24-h IOP curve obtained in a hospital sleep laboratory for 32 patients with POAG with known progression. The 24-h IOP curve demonstrated a wider range (6.9 ± 2.9 vs. 3.8 ± 2.3 mmHg; p < 0.001) and a higher peak IOP for 62% of patients when compared to office-based measurements [6]. In a prospective study, 103 patients with newly diagnosed POAG and pseudoexfoliation glaucoma (PXG) underwent 24-h IOP monitoring in a hospital sleep laboratory prior to initiating glaucoma therapy. Compared to POAG, the PXG patients demonstrated a wider range of IOP (13.5 vs. 8.5 mmHg; p < 0.001), higher peak IOP (38.2 vs. 26.9 mmHg; p < 0.001), and higher minimum IOP (24.7 vs. 18.4 mmHg; p < 0.001). In addition, 45% of PXG and 22.5% of POAG patients recorded their peak level of IOP outside standard office hours [7].

At present, hospitalization in a sleep laboratory for serial measurements is required to obtain a patient’s 24-h IOP curve, which is both cumbersome and expensive [8]. In addition, the gold standard for measuring IOP, Goldmann applanation tonometry (GAT), can be influenced by multiple variables that include pachymetry, keratometry, the amount of fluorescein in the tear film, Valsalva, eye position, and interobserver error [9, 10].

In the era of advanced bioinformatics, there is a need for a more accurate and precise method of continuous IOP monitoring, which will allow physicians to better understand the nature of their patient’s disease process and thus improve treatment regimens. Devices that are currently available and in development fall into three main categories: patient self-monitoring, temporary continuous monitoring, and permanent continuous monitoring (Table 1).

Table 1.

Current devices for 24-h IOP monitoring

| Characteristics | Icare® | Icare® Home | Triggerfish® | EyeMate® |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IOP monitoring |

Temporary Intermittent |

Temporary Intermittent |

Temporary Continuous |

Permanent Continuous |

| Accessibility | Worldwide | Europe | Worldwide | Europe |

| Data retrieval |

Activity log Patient account |

Activity log Memory card |

Activity log External reader Cloud-based server |

Activity log External reader Cloud-based server |

| Accessories | Handheld device | Handheld device |

External reader Periocular antenna |

External reader |

| Clinic-based commitment | Training session | Training session |

Training session Application removal |

Surgical implantation Postoperative care |

| Non-clinician participation | Patient and second participant | Patient only | Patient only | Patient only |

| Patient risk | Low | Low | Low–moderate | Moderate–high |

IOP intraocular pressure

This article is a systematic review of current devices for 24-h IOP monitoring that follows the principles of the Rapid Evidence Assessment methodology. It is based on previously conducted studies and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Self-Monitoring Devices

Many handheld, portable self-monitoring devices have been proposed and evaluated on the basis of ease of use, portability, safety profile, reliability, and accuracy.

The Tono-Pen (Reichert Technologies, Depew, NY, USA) [11] is a portable device that relies on the principles of applanation tonometry to measure IOP. It is reputable for its strong correlation with Goldmann applanation at physiologic pressures [12, 13] and is widely used in a variety of clinical settings. However, it has not been advocated for home self-monitoring because it requires the use of a topical anesthetic, which is associated with corneal endothelial toxicity [14, 15].

In 1998, it was suggested that IOP has a direct correlation to the amount of external pressure that needs to be applied to the ocular surface to create a visual aura, or phosphene. On the basis of these observations, the Proview Eye Pressure Monitor (Bausch and Lomb, Rochester, NY, USA) was introduced. The device has a circular tip that is applied to the eyelid at the superonasal quadrant, and the patient applies increasing external pressure until a visual aura is produced and the corresponding IOP is then recorded. The device is portable, does not require a topical anesthetic, and is easy and safe to use. However, clinical studies have shown a poor correlation with GAT and Tono-Pen measurements [14, 16–18].

Dekking and Coster first described the principle of rebound tonometry (RT) in 1967 [19, 20]. This discovery led to the development of the iCare tonometer (iCare Finland) [21], which was introduced in the USA in 2007. It is a handheld device that consists of a metallic motion probe with a plastic tip that is poised in a coil system. The probe accelerates towards the cornea within a magnetic field at a speed of 0.25–0.35 m/s. The tonometer estimates the IOP based on the deceleration parameters of the probe as it rebounds from the cornea. Once six reliable measurements are recorded, the maximum and minimum values are discarded before the average IOP is calculated on the basis of the remaining four measurements [22].

No topical anesthetic is required and the iCare tonometer has demonstrated a strong correlation with Goldmann applanation [22–24]. However, it has been noted that corneal properties, which include central corneal thickness (CCT), corneal hysteresis (CH), and corneal resistance factor (CRF), can affect the accuracy of IOP measurements [25, 26]. The iCare tends to overestimate IOP when compared to GAT in patients with thicker CCT [22–24] but is more reliable at the peripheral cornea [27, 28] and is independent of corneal curvature [29].

In addition, the reliability and accuracy decline when there is misalignment, which can be influenced by head position, dexterity, and eye movement. The traditional iCare model may be used in the upright or lateral decubitus position but is unable to measure supine IOP because of probe displacement when the device is inverted [14, 16, 22, 30]. The new iCare Pro has a built-in inclination sensor that allows IOP measurements in the supine position [31]. The US model and iCare Pro require the participation of a separate observer but can be easily used by non-specialized personnel with minimal training.

There are two iCare models designed for self-monitoring that are currently available outside the USA, namely the iCare Home (Fig. 1) and its predecessor, the iCare One. Clinical trials have demonstrated that self-monitoring IOP measurements taken by iCare One have a strong correlation to GAT measurements with patients reporting subjective ease of use [32–34]. The current updates to the iCare design increase its potential for widespread use as a portable IOP self-monitoring device.

Fig. 1.

Icare® Home (Icare Finland Oy) self-monitoring device

In one study, the concurrent measurements using the self-monitoring iCare One and clinician-obtained GAT IOP were compared for 149 patients with ocular hypertension (OHT) and glaucoma. The iCare One IOP values were within 3 mmHg of corresponding GAT values for 67.1% of patients. The differences noted between the iCare One and GAT were not significant (p = 0.41) if the dominant hand was used for self-monitoring. In addition, more than 77% of participants reported ease of use with the iCare One [34].

A recent study investigated the accuracy of self-obtained, partner-obtained, and trainer-obtained iCare Home IOP measurements compared to GAT. After a standardized training regimen, 74% of subjects were able to successfully use the iCare Home for self-monitoring. The acceptability questionnaire revealed that the device was easy to use (84%), measurements were quick to obtain (88%), and the device was comfortable (95%). However the iCare Home was inclined to underestimate the IOP compared to GAT: self-obtained IOP, 0.3 mmHg (95% CI −4.6 to 5.2 mmHg); partner-obtained IOP, 1.1 mmHg (95% CI −3.2 to 5.3 mmHg); and trainer-obtained IOP, 1.2 mmHg (95% CI −3.9 to 6.3 mmHg). Self-obtained iCare Home IOP measurements demonstrated the least discrepancy with GAT, although there was a greater difference noted for CCT below 500 mm and above 600 mm [35].

Temporary Continuous Monitoring Devices

In the 1970s, Greene and Gilman proposed the use of contact lenses for continuous IOP monitoring. They embedded two strain gauges in a soft contact lens and measured the changes in the meridional angle of the cornea–scleral junction to assess fluctuations in IOP [36]. Given the necessity to custom fit each contact lens, cost became an insurmountable barrier to its widespread use [37].

The next attempt followed a few decades later. Ziemer Ophthalmic Systems introduced a rigid gas-permeable contact lens (RGP) with a piezoresistive pressure sensor that was centered within the lens and seated flush to the posterior surface. Lead wires, extending from the anterior surface of the sensor, were attached to a base unit that would continuously record the patient’s IOP [38]. Twa et al. demonstrated that measurements were comparable to dynamic contour tonometry in the seated position [39]. However, there were several drawbacks noted with this model design. The sensor was placed directly in the visual axis, thus impeding vision. Patients also reported subjective discomfort with RGP wear. In addition, the central processing unit needed to be supported and carried with caution to prevent external vector forces that would influence IOP readings [37, 39].

Since then, the Swiss company Sensimed has introduced the Triggerfish contact lens sensor (CLS), which is currently approved in Europe and has recently been approved by the Food and Drug Administration in the USA [40]. The device is based on the principle that small changes in ocular circumference, measured at the cornea–scleral junction, correspond to changes in intraocular pressure and volume, as well as ocular biomechanical properties. The underlying assumption is that 1 mmHg in IOP is equivalent to a 3-μm change in the radius of curvature of the cornea [37, 41, 42].

The device itself is a soft silicone contact lens embedded with a circumferential sensor consisting of two platinum–titanium strain gauges that measure changes in the radius of curvature of the cornea (Fig. 2). To ensure a good fit, there are three different base curves available. An embedded microprocessor transmits an output signal to an adhesive wireless antenna that is secured externally to the periocular surface. The wireless antenna recharges the microprocessor and simultaneously receives continuous data, as measured in units of electrical voltage. The data is transferred by a cable wire to a portable recorder worn at the patients side, which allows the patient to be ambulatory. Each data set consists of 300 data points acquired during a 30-s interval that occurs every 5 min, which is equivalent to 288 data sets in 24 h [37, 41, 42].

Fig. 2.

Triggerfish® (Sensimed AG) contact lens sensor

In vitro studies have demonstrated that the Triggerfish CLS produces reliable measurements of IOP during ocular pulsations and linear changes of a known control [43]. Clinical trials have highlighted that transient blurred vision and hyperemia are the most common patient complaints; but more importantly, no serious adverse events have been reported [37, 42]. To date, the Triggerfish CLS has been used to study the circadian pattern in healthy individuals, as well as those with POAG, NTG, PXG [44, 45] and patients with thyroid eye disease [46].

Use of the CLS has provided new insights into the effects of selective laser trabeculoplasty (SLT). In a prospective study, 18 NTG patients underwent SLT. Their baseline and 1-month 24-h IOP curves were obtained with the Triggerfish CLS for comparison. Patients with successful treatment, as defined by an IOP reduction of at least 20% by GAT, displayed a 24.6% reduction of mean global variability at 1 month. There was no change in signal variability noted in the success group, whereas the patients that failed treatment demonstrated an increase in diurnal variability [47]. A similar study compared the baseline, 1-month, and 2-month CLS 24-h IOP curves for 10 patients with NTG who underwent SLT. In patients that were successfully treated, the range of IOP fluctuations during the diurnal period remained unchanged while the fluctuations during the nocturnal period decreased from 290 ± 86 mV Eq to 199 ± 31 mV Eq after treatment (p = 0.014) [48].

In regards to topical medications, the Triggerfish CLS has struggled to demonstrate significant changes in the 24-h IOP curve after treatment when compared to baseline readings. Mansouri et al. captured the CLS 24-h IOP patterns in 23 patients with POAG before and after 1-month treatment with one of four glaucoma medication drug classes. Prostaglandin analogues revealed flattening of the nocturnal IOP rise that accompanies the transition from upright to supine but did not exhibit an affect on the acrophase or signal amplitude. All other medication classes failed to demonstrate an effect on the circadian 24-h IOP patterns [49]. In another study, nine patients with OHT and POAG underwent a 6-week medication washout. Three baseline 24-h IOP curves were taken including two CLS and one GAT curve. The patients were placed on travoprost monotherapy for 3 months before three additional 24-h IOP curves were obtained. The 24-h GAT IOP curve decreased from 22.91 ± 5.11 mmHg to 18.24 ± 2.49 mmHg (p < 0.001) after treatment. In contrast, the CLS curves showed no significant difference (mean value p = 0.273, SD p = 0.497). All CLS 24-h IOP curves demonstrated a trend for time-dependent increase with continued wear, and no IOP changes related to postural changes (supine vs. erect) were identified [50].

More recently, 24-h IOP profiles obtained with the Triggerfish CLS have been associated with the rate of visual field progression in glaucoma patients. In this prospective, open-label study, 34 patients with POAG were divided into two equal groups of fast and slow progressors on the basis of previous perimetric trends from eight or more visual fields administered over 2 years. Each patient obtained a 24-h CLS IOP curve. For each additional awake large peak, the rate of progression based on the mean deviation (MD) slopes accelerated by −0.14 dB/year, each 10 unit increase in sleeping mean peak ratio was associated with an acceleration of −0.20 dB/year, and for every 10-unit increase in mean peak ratio while awake the accelerated rate of progression was −0.07 dB/year [51]. This suggests that the main utility of the CLS data may come from the 24-h IOP profile and ability to detect short- and long-term IOP fluctuations as a result of medications, activity, and body position.

Currently, the Triggerfish CLS is the only commercially available device for temporary continuous 24-h IOP monitoring [40]. It is non-invasive and has a low risk profile. One major advantage of the CLS is that patients can be ambulatory during the measurements, rather than being housed in a 24-h sleep laboratory, therefore providing a more accurate individual IOP profile that reflects a patient’s typical daily routine. The amount of data received per patient is abundant and has the potential to provide new insights as to how eye position, blinks, topical medications, laser and surgical interventions, as well as lifestyle can affect a patient’s circadian IOP pattern.

With every technological advancement there are new challenges to overcome. One major obstacle encountered with the Triggerfish CLS is that the data is recorded in millivolt equivalents rather than millimeters of mercury. The conversion of millivolt equivalents to millimeters of mercury is complex because the relationship between volume and pressure is non-linear and is influenced by the viscoelastic properties of the eye. New algorithms need to be developed to translate the data and validate its correlation to our current standards for IOP measurement. In addition, cost of the device may become an obstacle to more widespread use [16, 37, 52].

Permanent Continuous Monitoring Devices

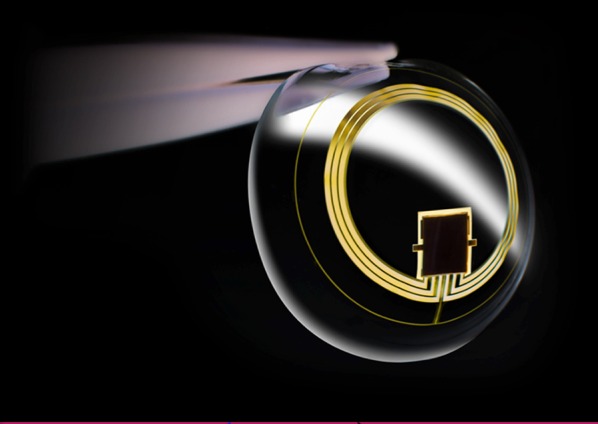

A German company has introduced an implantable intraocular device that is currently being vetted through human clinical trials. The Implandata EyeMate is a wireless intraocular transducer (WIT) that consists of eight pressure and temperature sensors, an identification and analog-to-digital encoder, as well as a telemetry unit. The electronic components are attached to a gold circular antenna and the entire device is encapsulated in platinum-cured silicone. Each component is either inert or biocompatible. The outside diameter is 11.3 mm, with an inside diameter of 7 mm, thickness of 0.9 mm, and weighs 0.1 g. The design is compatible with ciliary sulcus placement. Although the electronic component is rigid, the remainder of the device is malleable and can be folded for intraocular implantation [53, 54].

Each pressure sensor is composed of two parallel plates, a thin flexible plate that indents with changes in IOP and a thicker rigid base plate. As the distance between the two plates varies with changes in IOP, a corresponding analog signal is generated. This analog signal is converted to a digital signal that is transmitted externally by radiofrequency. A handheld reader unit receives the digital data and visually displays the IOP value. The reader and the intraocular transponder unit must be within 5 cm of each other before the reader can activate the electromagnetic coupling sequence and the two units can correspond with each other. The device can obtain up to ten IOP measurements per second and there are a range of settings that allow for monitoring at variable intervals [53, 54].

The handheld reader also charges the WIT externally through electromagnetic inductive coupling. The base unit can store up to 3000 IOP measurements and additional memory modules can be added to the reader device. An optional wireless module can be installed to automatically download all measured data to a cloud-based server, allowing the clinical provider easy and instantaneous access to the data [53, 54].

In vitro studies have demonstrated the lasting durability of the EyeMate as a wireless IOP transducer. According to Implandata, their WIT device was soaked in saline for 4 years and continued to remain functional, thus establishing its potential for endurance in aqueous solution. In addition, six devices were immersed in saline for 515 days and were subjected to an absolute test pressure of 1000 hPa (sea level) at 36 °C. The average drift in intraocular pressure was 3.47 mmHg compared to the calculated drift rate of 2.46 mmHg, confirming that the measurements taken maintained a practical precision when tested under simulated physiologic conditions [55]. In vitro studies have demonstrated that the Implandata EyeMate is biocompatible with good subjective tolerance in rabbit eyes for up to 25 months. This was confirmed by the lack of intraocular toxicity on histopathology [55, 56].

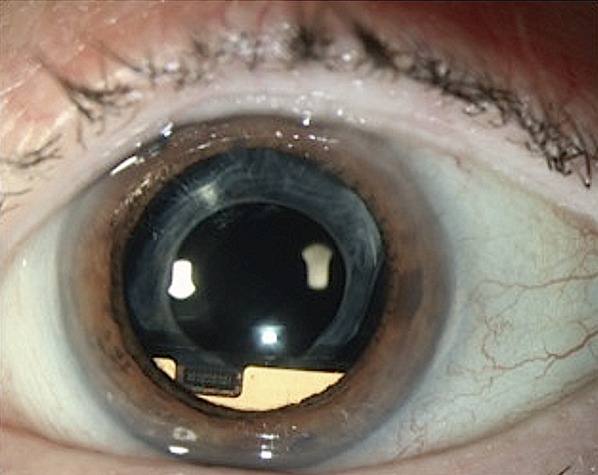

In the ARGOS-O1 study, six patients with well-controlled POAG or NTG and visually significant cataracts underwent an uneventful cataract surgery and sulcus placement of the Implandata EyeMate (Fig. 3), which was confirmed by ultrasound biomicroscopy. Four patients demonstrated a significant postoperative inflammatory response that lasted up to 9 days and was successfully treated with topical and oral steroids. At 1 year postoperatively, all patients maintained control of their glaucoma and there was no incidence of pupillary block, angle closure, corneal edema, retinal detachment, endophthalmitis, bleeding, macular edema, or visual deterioration. The endothelial cell count and central corneal thickness remained stable in all patients [57].

Fig. 3.

ARGOS intraocular pressure sensor.

Republished with permission of the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology from Koutsonas et al. [57]; permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.

Although the telemetric intraocular pressure curves for all patients were comparable to the circadian pattern outlined by consecutive IOP measurements by GAT, three patients had a significant positive shift in their telemetric IOP curves after 5–6 months and one patient consistently had a negative telemetric IOP curve despite stable GAT readings. The sensor’s unpredictable variance leads to issues concerning the interpretation and clinical application of the WIT telemetric curves. Consecutive GAT measurements are likely to be necessary as a benchmark for comparison until we are able to formulate guidelines for interpretation based on additional evidence-based research [57].

Currently, there is an open enrollment for a prospective, multicenter clinical trial to assess the safety and efficacy of the device for patients with POAG [58]. The device is promising and clinicians are eagerly awaiting further clinical data before the Implandata EyeMate will become commercially available for patient care.

Meanwhile, several other companies are also working to develop a biocompatible and effective wireless intraocular IOP sensor. AcuMEMS (Menlo Park, CA, USA) has developed an implantable sensor technology, called the iSense System. The company is currently testing two different devices, one that can be placed in the anterior chamber as a stand-alone procedure and one that can be placed in the capsular bag in conjunction with cataract surgery. Both have shown initial success in animal trials [59]. LaunchPoint Technologies (Goleta, CA) is currently developing an intraocular sensor that can be attached directly to an intraocular lens or injected into the vitreous cavity [60, 61]. All of these intraocular sensors are considered “passive” wireless devices that are dependent on the proximity of an external reader to charge the internal unit and extract data. Solx (Waltham, MA) is pursuing an “active” wireless intraocular sensor that will be independent of an external reader [62, 63].

Conclusion

With the advent of new technologies and a growing emphasis on bioinformatics, customized treatment regimens will become the standard of care for glaucoma. A reliable, accurate, mobile 24-h IOP monitoring device will provide a novel understanding of a patient’s individual IOP circadian pattern. It may allow for a paradigm shift in the way we interpret and treat glaucoma. However, with each innovation there are new challenges that include novel methods of data collection, portability, tolerance with long-term use, and the cost per device. With time, these challenges will be addressed and our patients will be offered a variety of options for 24-h IOP monitoring.

Acknowledgments

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval for the version to be published.

Disclosures

Malik Y. Kahook, Leonard K. Seibold, and Kaweh Mansouri have consulted for Sensimed AG. Sabita M. Ittoop and Jeffrey R. SooHo declare that they have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is a systematic review of current devices for 24-h IOP monitoring that follows the principles of the Rapid Evidence Assessment methodology. It is based on previously conducted studies and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Footnotes

Enhanced content

To view enhanced content for this article go to http://www.medengine.com/Redeem/23E4F06031FE36D5.

References

- 1.Tham YC, Li X, Wong TY, Quigley HA, Aung T, Cheng CY. Global prevalence of glaucoma and projections of glaucoma burden through 2040: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. 2014:121;2081–90. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Quigley HA, Broman AT. The number of people with glaucoma worldwide in 2010 and 2020. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90(3):262–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Sit AJ. Continuous monitoring of intraocular pressure: rationale and progress toward a clinical device. J Glaucoma. 2009;18(4):272–279. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e3181862490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Orzalesi N, Rossetti L, Invernizzi T, Bottoli A, Autelitano A. Effect of timolol, latanoprost, and dorzolamide on circadian IOP in glaucoma or ocular hypertension. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41(9):2566–2573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hughes E, Spry P, Diamond J. 24-hour monitoring of intraocular pressure in glaucoma management: a retrospective review. J Glaucoma. 2003;12(3):232–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Barkana Y, Anis S, Liebmann J, Tello C, Ritch R. Clinical utility of intraocular pressure monitoring outside of normal office hours in patients with glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124(6):793–797. doi: 10.1001/archopht.124.6.793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Konstas AG, Mantziris DA, Stewart WC. Diurnal intraocular pressure in untreated exfoliation and primary open-angle glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;115(2):182–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Liu JHK, Weinreb RN. Monitoring intraocular pressure for 24 h. Br J Ophthalmol. 2011;95:599–600. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Whitacre MM, Stein R. Sources of error with use of Goldmann-type tonometers. Surv Ophthalmol. 1993;38:1–30. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Akram A, Yaqub A, Dar AJ, Fiaz. Pitfalls in intraocular pressure measurement by Goldmann-type applanation tonometers. Pak J Ophthalmol. 2009;25:22–4.

- 11.http://www.reichert.com/eye_care.cfm. Accessed 1 Jan 2016.

- 12.Hessemer V, Rössler R, Jacobi KW. Tono-Pen, a new tonometer. Int Ophthalmol. 1989;13:51–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Kao SF, Lichter PR, Bergstrom TJ, Rowe S, Musch DC. Clinical comparison of the Oculab Tono-Pen to the Goldmann applanation tonometer. Ophthalmology. 1987;94(12):1541–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Liang SYW, Lee GA, Shields D. Self-tonometry in glaucoma management-past, present and future. Surv Ophthalmol. 2009:54;450–62. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Judge AJ, Najafi K, Lee DA, Miller KM. Corneal endothelial toxicity of topical anesthesia. Ophthalmology. 1997;104(9):1373–1379. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(97)30128-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Smedt S. Noninvasive intraocular pressure monitoring: current insights. Clin Ophthalmol. 2015;9:1385–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Rietveld E, van den Bremer DA, Völker-Dieben HJ. Clinical evaluation of the pressure phosphene tonometer in patients with glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol. 2005;89(5):537–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Li J, Herndon LW, Asrani SG, Stinnett S, Allingham RR. Clinical comparison of the Proview eye pressure monitor with the Goldmann applanation tonometer and the Tonopen. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004;122(8):1117–21. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Dekking HM, Coster HD. Dynamic tonometry. Ophthalmologica. 1967;154:59–75. doi: 10.1159/000305149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cervino A. Rebound tonometry: new opportunities and limitations of non-invasive determination of intraocular pressure. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90(12):1444–1446. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.102970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.http://icare-usa.com. Accessed 1 Jan 2016.

- 22.Iliev ME, Goldblum D, Katsoulis K, Amstutz C, Frueh B. Comparison of rebound tonometry with Goldmann applanation tonometry and correlation with central corneal thickness. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90(7):833–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Salim S, Du HWJ. Comparison of intraocular pressure measurements and assessment of intraobserver and interobserver reproducibility with the portable ICare rebound tonometer and Goldmann applanation tonometer in glaucoma patients. J Glaucoma. 2013;22(4):325–329. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e318237caa2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brusini P, Salvetat ML, Zeppieri M, Tosoni C, Parisi L. Comparison of ICare tonometer with Goldmann applanation tonometer in glaucoma patients. J Glaucoma. 2006;15(3):213–217. doi: 10.1097/01.ijg.0000212208.87523.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shin J, Lee JW, Kim EA, Caprioli J. The effect of corneal biomechanical properties on rebound tonometer in patients with normal-tension glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;159(1):144–154. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jorge JMM, González-Méijome JM, Queirós A, Fernandes P, Parafita MA. Correlations between corneal biomechanical properties measured with the ocular response analyzer and ICare rebound tonometry. J Glaucoma. 2008;17(6):442–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.González-Méijome JM, Jorge J, Queirós A, et al. Age differences in central and peripheral intraocular pressure using a rebound tonometer. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90(12):1495–1500. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.103044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muttuvelu DV, Baggesen K, Ehlers N. Precision and accuracy of the ICare tonometer—peripheral and central IOP measurements by rebound tonometry. Acta Ophthalmol. 2012;90(4):322–326. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2010.01987.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jóhannesson G, Hallberg P, Eklund A, Lindén C. Pascal, ICare and Goldmann applanation tonometry–a comparative study. Acta Ophthalmol. 2008;86(6):614–21. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Rosentreter A, Jablonski KS, Mellein AC, Gaki S, Hueber A, Dietlein TS. A new rebound tonometer for home monitoring of intraocular pressure. Graefe’s Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2011;249(11):1713–1719. doi: 10.1007/s00417-011-1785-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim KN, Jeoung JW, Park KH, Yang MK, Kim DM. Comparison of the new rebound tonometer with Goldmann applanation tonometer in a clinical setting. Acta Ophthalmol. 2013;91(5):e392–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Sakamoto M, Kanamori A, Fujihara M, Yamada Y, Nakamura M, Negi A. Assessment of IcareONE rebound tonometer for self-measuring intraocular pressure. Acta Ophthalmol. 2014;92(3):243–248. doi: 10.1111/aos.12108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Halkiadakis I, Stratos A, Stergiopoulos G, et al. Evaluation of the Icare-ONE rebound tonometer as a self-measuring intraocular pressure device in normal subjects. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2012;250(8):1207–1211. doi: 10.1007/s00417-011-1875-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moreno-Montañés J, Martínez-de-la-Casa JM, Sabater AL, Morales-Fernandez L, Sáenz C, Garcia-Feijoo J. Clinical evaluation of the new rebound tonometers Icare PRO and Icare ONE compared with the Goldmann tonometer. J Glaucoma. 2015;24(7):527–32. doi:10.1097/IJG.0000000000000058. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Dabasia PL, Lawrenson JG Murdoch IE. Evaluation of a new rebound tonometer for self-measurement of intraocular pressure. Br J Ophthalmol. 2015. doi:10.1136/bjophthalmol-2015-307674. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Greene M, Gilman B. Intraocular pressure measurement with instrumented contact lenses. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1974;13(4):299–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mansouri K. The road ahead to continuous 24-hour intraocular pressure monitoring in glaucoma. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2014;9(2):260–268. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.http://www.ziemergroup.com/products/pascal/dct-lens.html. Accessed 1 Jan 2016.

- 39.Twa MD, Roberts CJ, Karol HJ, Mahmoud AM, Weber PA, Small RH. Evaluation of a contact lens-embedded sensor for intraocular pressure measurement. J Glaucoma. 2010;19(6):382–390. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e3181c4ac3d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm489308.htm. Accessed 4 Mar 2016.

- 41.http://www.sensimed.ch/en/sensimed-triggerfish/sensimed-triggerfish.html. Accessed 1 Jan 2016.

- 42.Mansouri K, Medeiros FA, Tafreshi A, Weinreb RN. Continuous 24-hour monitoring of intraocular pressure patterns with a contact lens sensor: safety, tolerability, and reproducibility in patients with glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130(12):1534–1539. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2012.2280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Leonardi M, Pitchon EM, Bertsch A, Renaud P, Mermoud A. Wireless contact lens sensor for intraocular pressure monitoring: assessment on enucleated pig eyes. Acta Ophthalmol. 2009;87(4):433–437. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2008.01404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Agnifili L, Mastropasqua R, Frezzotti P, et al. Circadian intraocular pressure patterns in healthy subjects, primary open angle and normal tension glaucoma patients with a contact lens sensor. Acta Ophthalmol. 2015;93(1):e14–e21. doi: 10.1111/aos.12408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tojo N, Hayashi A, Otsuka M, Miyakoshi A. Fluctuations of the intraocular pressure in pseudoexfoliation syndrome and normal eyes measured by a contact lens sensor. J Glaucoma. 2016;25(5):e463–8. doi:10.1097/IJG.0000000000000292. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Parekh AS, Mansouri K, Weinreb RN, Tafreshi A, Korn BS, Kikkawa DO. Twenty-four-hour intraocular pressure patterns in patients with thyroid eye disease. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2015;43(2):108–14 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Lee JWY, Fu L, Chan JCH, Lai JSM. Twenty-four-hour intraocular pressure related changes following adjuvant selective laser trabeculoplasty for normal tension glaucoma. Medicine (Baltimore). 2014;93(27):e238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Tojo N, Oka M, Miyakoshi A, Ozaki H, Hayashi A. Comparison of fluctuations of intraocular pressure before and after selective laser trabeculoplasty in normal-tension glaucoma patients. J Glaucoma. 2013;23(8):138–43. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Mansouri K, Medeiros F, Weinreb R. Effect of glaucoma medications on 24-hour intraocular pressure-related patterns using a contact lens sensor. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2015;43(9):787–795. doi: 10.1111/ceo.12567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Holló G, Kóthy P, Vargha P. Evaluation of continuous 24-hour intraocular pressure monitoring for assessment of prostaglandin-induced pressure reduction in glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2014;23(1):e6–12. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.De Moraes CG, Jasien JV, Simon-Zoula S, Liebmann JMRR. Visual field change and 24-hour IOP-related profile with a contact lens sensor in treated glaucoma patients. Ophthalmology. 2015;15:S0161–S6420. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mansouri K, Weinreb RN. Meeting an unmet need in glaucoma: continuous 24-h monitoring of intraocular pressure. Expert Rev Med Dev. 2012;9:225–231. doi: 10.1586/erd.12.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Melki S, Todani A, Cherfan G. An implantable intraocular pressure transducer: initial safety outcomes. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014;132(10):1221–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.http://implandata.com/en/. Accessed 1 Jan 2016.

- 55.Todani A, Behlau I, Fava MA, et al. Intraocular pressure measurement by radio wave telemetry. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(13):9573–80. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56.Kim Y, Kim M, Park K, et al. Preliminary study on implantable inductive-type sensor for continuous monitoring of intraocular pressure. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2015;43(9):830–837. doi: 10.1111/ceo.12573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Koutsonas A, Walter P, Roessler G, Plange N. Implantation of a novel telemetric intraocular pressure sensor in patients with glaucoma (ARGOS study): 1-year results. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56(2):1063–1069. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-14925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02434692. Accessed 1 Jan 2016.

- 59.http://www.aao.org/interview/technology-advances-in-iop-monitoring. Accessed 1 Jan 2016.

- 60.http://www.launchpnt.com/portfolio/biomedical/. Accessed 1 Jan 2016.

- 61.Varel Ç, Shih Y-C, Otis BP, Shen TS, Böhringer KF. A wireless intraocular pressure monitoring device with a solder-filled microchannel antenna. J Micromech Microeng. 2014;24(4):045012.

- 62.http://eyetubeod.com/series/Glaucoma-Today-Journal-Club/ebesi/. Accessed 1 Jan 2016.

- 63.Chow EY, Chlebowski AL, Irazoqui PP. A miniature-implantable RF-wireless active glaucoma intraocular pressure monitor. IEEE Trans Biomed Circuits Syst 2010;4:340–9. [DOI] [PubMed]