Abstract

In order for the global healthcare system to remain sustainable, healthcare spending needs to be reduced, and self-treating certain conditions under the guidance of a pharmacist provides a means of accomplishing this goal. This article was developed to describe global healthcare trends affecting self-care with a specific focus on the role of the pharmacist in facilitating over-the-counter (OTC) medication management. Potential healthcare-related economic benefits associated with the self-care model are outlined. The importance of the collaboration between healthcare providers (HCPs), including specialists, primary care providers, and pharmacists, is also discussed. The evolving role of the pharmacist is examined and recommendations are provided for ways to successfully engage with other HCPs and consumers to optimize the pharmacist’s unique qualifications and accessibility in the community. Using the management of frequent heartburn with an OTC proton-pump inhibitor as a model, the critical role of the pharmacist in patient self-treatment of certain symptoms will be discussed based on the World Gastroenterology Organization’s recently published guidelines for the community-based management of common gastrointestinal symptoms. As the global healthcare system continues to evolve, self-care is expected to have an increasing role in treating certain minor ailments, and pharmacists are at the forefront of these changes. Pharmacists can guide individuals in making healthy lifestyle choices, recommend appropriate OTC medications, and educate consumers about when they should consult a physician.

Funding: Pfizer Inc.

Keywords: Community pharmacies, Health economics, Health literacy, Heartburn/reflux, Self-care

Introduction

The global healthcare system is expected to undergo significant changes in the coming decades to remain economically viable, and self-care and self-medication will likely become important for driving these changes. The authors, who provided the concept and developed the content for this review, are experts in the area of self-care and describe the various and related aspects of this treatment model, as well as the role of self-care in the future of the global healthcare system.

John Bell, AM, BPharm, FPS, FRPharmS, FACPP, MSHP, the Principal Advisor to the Pharmaceutical Society of Australia’s Self-Care Program, has authored Importance of Self-Care in the Future of Quality Affordable Medicine in the Twenty First Century, which defines self-care and describes its key stakeholders and components, including the importance of enhancing health literacy. The potential financial savings of shifting from physician-based care to self-care is also discussed. Additionally, Mr. Bell discusses The Role of the Pharmacist in Self-Care: A Prescription for the Future. Because pharmacists are ideally placed to provide healthcare advice, the pharmacist’s role as healthcare provider (HCP) will continue to expand. Pharmacists not only fill prescriptions but also educate consumers about the importance of healthy lifestyle choices, recommend over-the-counter (OTC) treatments, perform medication monitoring, and refer consumers to physicians as necessary.

Gerald Dziekan, MD, MSc, is the Director General of the World Self-Medication Industry whose section Why Self-Care? A Public Health and Health Economic Perspective on the Benefits of Self-Care describes ways that self-care, and in particular, self-medication, can positively affect public health and reduce the economic burden of managing minor ailments and some chronic conditions by shifting care to the consumer with guidance from pharmacists and physicians.

Varocha Mahachai, MD, FRCP, is the Director of the Gastrointestinal & Liver Center for Bangkok Medical Center and Professor at Chulalongkorn University. Her section, Reflux and Heartburn as a Self-Care Model, describes the number of OTC treatments available for treating acid reflux-related symptoms, including recent switches of proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs) from prescription to OTC. With these readily available treatments, pharmacists can help consumers effectively and safely manage their acid reflux-related symptoms. Pharmacists can also help limit the risk for heartburn treatments masking more serious underlying conditions.

Within different sections, this article describes factors affecting the global healthcare system, and through examples such as the increasing availability of OTC PPIs also describes the roles that self-care and pharmacists can play in sustaining the economic viability of that system by shifting a portion of the costs for caring for some minor ailments to consumers.

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Importance of Self-Care in the Future of Quality Affordable Medicine in the Twenty First Century

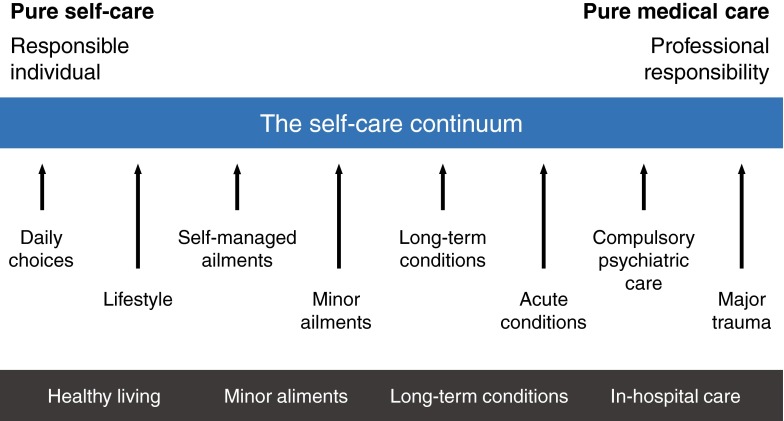

Self-care is characterized by healthcare consumers who take proactive roles in identifying and managing their health conditions to optimize their overall physical health and psychological and spiritual well-being [1, 2]. Self-care has been described as existing on a continuum, with purely self-initiated activities such as preventative healthy lifestyle choices on one end and treatment for acute minor ailments and maintenance therapy for certain chronic conditions on the other (Fig. 1) [1, 3, 4]. Effective self-care requires active collaboration between consumers and HCPs, including pharmacists, and is reliant on well-informed consumers and HCPs with effective communication skills [5]. Consumers are supportive of the concept of self-care, which they view as an essential feature of their healthcare, yet few consumers are confident that they can effectively manage their own health [5].

Fig. 1.

The self-care continuum [1].

Adapted with permission from the Self Care Forum of the United Kingdom

Webber et al. [6] describe several key domains and behaviors of self-care. Health literacy is a key component of self-care and is broadly defined as an individual’s ability to acquire and understand information related to their healthcare. Self-care is also reliant on an individual’s awareness of their physical and mental health, including awareness of their current health status (e.g., body mass index, cholesterol, blood pressure), which requires receiving regular health screenings. Self-care also involves engaging in regular physical activity, such as moderate levels of exercise (e.g., walking, cycling), eating a healthy, nutritious diet with appropriate caloric intake, and having good hygiene, including proper dental care. In addition, effective self-care involves avoiding and mitigating potential health risks, such as eliminating tobacco use, limiting alcohol consumption, and receiving vaccinations, as well as using products, services, diagnostics, and medicines rationally and responsibly. These authors suggest that identifying domains where an individual is lacking can allow for developing a personalized self-care index that addresses potential deficits in self-care with an action plan, including identifying areas where guidance (e.g., from an HCP) is necessary.

Self-care is reliant on enhancing consumers’ health literacy to ensure that they can process the health-related information that they obtain on their own or from HCPs and allow for making informed healthcare decisions [5, 7]. Limited health literacy is common, particularly in those who are older, from lower socioeconomic strata, and with limited education [7]. Estimates in the United States suggest that 36% of the adult population has basic or below basic health literacy, while in Australia it has been estimated that approximately 60% of the population has below the minimum health literacy necessary to meet the demands of everyday life and work “in the emerging knowledge-based economy” [8, 9]. The consequences of poor health literacy include an inability to communicate needs to HCPs, a limited ability to understand instructions for taking prescription medicines, higher hospitalization rates, and, implicitly, higher healthcare costs [7].

Self-care can contribute substantially to easing financial pressures on the healthcare system by shifting the cost of care for some relevant conditions from physicians to consumers while also enhancing healthcare outcomes [3, 10]. Empowering pharmacists and establishing community pharmacies that serve as cost-effective resource centers for providing authoritative, objective, evidence-based information/advice and directions for the appropriate use of various treatments is a goal of self-care that is of interest to consumers [11–13]. Pharmacists have a necessary role in screening for certain conditions, making self-care treatment recommendations, and/or providing referral support as needed. Programs have been implemented to meet this goal, including the Health Destination Pharmacy program in Australia, which seeks to position pharmacists as primary HCPs who emphasize self-care [13]. A study of participants in this program reported benefits for the pharmacy as a whole as well as for consumers despite a minority of pharmacies experiencing negative financial growth during the study period. The Global Respiratory Infection Partnership is another example of providing appropriate self-care information and advice through HCPs, including pharmacists, for managing upper respiratory tract infections (e.g., coughs, colds) without the use of antibiotics [14]. With the increasing incidence of antimicrobial resistance, pharmacists can play a role in advocating antibiotic stewardship by promoting use of self-care treatment options. These initiatives suggest that the expanding role of pharmacists as HCPs, particularly within the realm of self-care, can enhance outcomes and reduce the cost and resource burden on the healthcare system.

John Bell, AM, BPharm, FPS, FRPharmS, FACPP, MSHP, Principal Advisor to the Pharmaceutical Society of Australia’s Self-Care Program.

The Role of the Pharmacist in Self-Care: A Prescription for the Future

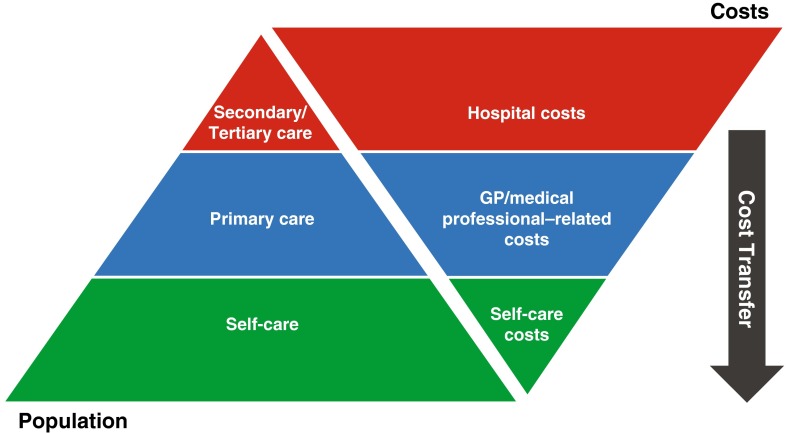

HCPs, in particular general practitioners (GPs), continue to be the primary source for treating minor ailments [5]. A study conducted in the United Kingdom (UK) reported that 13% of GP and 5% of emergency department (ED) hours were spent on consulting for minor ailments that could be managed in a community pharmacy setting [15]. In addition to managing certain chronic conditions, self-care, including self-medication, can help to shift the burden of treating these minor ailments from GPs to other HCPs, particularly pharmacists, and consumers themselves (Fig. 2) [3]. Pharmacists, a widely available and conveniently accessible healthcare resource [16], are ideally placed to meet the challenges of ever-evolving consumer needs and global healthcare systems [12]. In addition to supplying treatments prescribed by physicians, pharmacists can serve as integral partners in a collaborative care team of HCPs [3, 12]. Pharmacists are also involved with health promotion by screening for, and increasing the awareness of, certain conditions and discussing strategies such as making healthy lifestyle choices for preventing certain health issues [12].

Fig. 2.

Self-care pyramid [3]. From Self-Care: A Winning Solution for Citizens, Healthcare Professionals, Health Systems. Brussels: Association of the European Self-Medication Industry; 2012. Adapted with permission from the European Self-Medication Industry. GP general practitioner

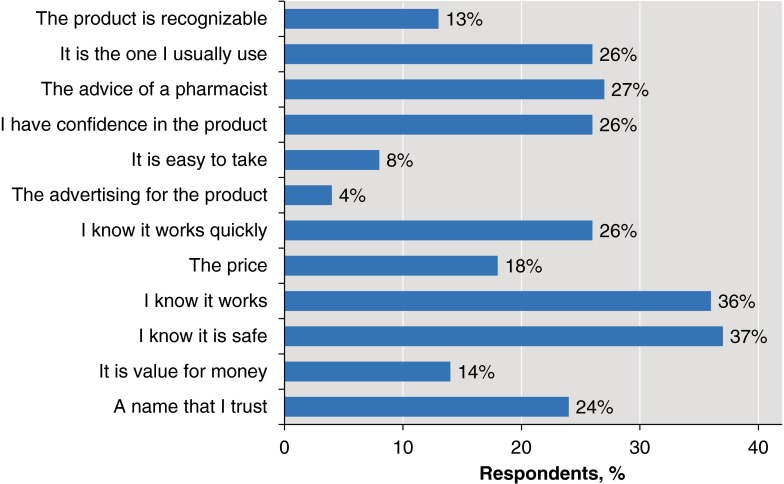

Self-medication is a key component of self-care [17]. Pharmacists provide valuable information to ensure that consumers receive treatments that are appropriate for a given condition [12]. Importantly, consumers view pharmacists as trusted resources for providing information about their healthcare [18]. When selecting a non-prescription medicine, consumers report that the advice of a pharmacist is one of the most important factors in making their decision (Fig. 3) [18]. Although pharmacists can be the first point of contact for some healthcare consumers, they are a relatively underutilized resource [5].

Fig. 3.

Important factors in choosing a non-prescription medicine [18]. Adapted from The Changing Landscape—A Multi-Country Study Undertaken With AESGP. Nielsen Global On‐Line Omnibus Mar/Apr 2009. © 2009 The Nielsen Company.

Adapted with permission

The potential benefits of consulting a pharmacist in the first instance include more immediate access versus having to wait for a GP appointment, as well as reducing travel time and healthcare-related costs [19]. Additionally, in many cases non-prescription/OTC products are less expensive than prescription medications [19], and as mentioned previously, the pharmacist is well positioned to refer consumers to a physician when symptoms indicate a potentially serious condition. A study conducted in the UK has demonstrated that individuals seeking treatment for minor ailments from an ED, a GP, or a community pharmacy had comparable symptomatic and quality-of-life outcomes [20]. However, the costs associated with receiving a consultation in the pharmacy setting were significantly lower than in the ED or GP setting. The key factors associated with selecting a point of care were location and convenience and prior experience with and perceived severity of the symptom that necessitated seeking treatment from an HCP. Some individuals presenting in the pharmacy setting had previously experienced the symptoms, as indicated by their often direct request for a specific treatment. In contrast, the majority of those seeking care from an ED were experiencing the symptom for the first time and the symptoms were perceived to be more severe. This effect may have confounded the cost analyses, but these data provide insights into the types of conditions that consumers are likely to self-treat in the pharmacy setting. A chronological review of policy changes in the UK suggested that continuing to reclassify medications used and providing free access to an HCP and free or low-cost treatment for minor ailments will further ease the burden of treating minor ailments in the GP setting while increasing access to healthcare services [21].

Utilizing self-care can enhance patients’ confidence by improving their skill set and empowering them to treat certain conditions on their own instead of always relying on an HCP [19]. For certain conditions, a collaborative care model where the individual is first diagnosed by a physician who provides an initial treatment plan is most appropriate [3]. After the initial diagnosis, the pharmacist is responsible for educating the consumer on identifying signs and symptoms of recurrence and ways to effectively self-treat these recurrences, as well as identifying circumstances when it is necessary to consult a physician again, for instance if symptom severity increases [22]. Pharmacists are also ideally placed to monitor for possible interactions between the multiple treatments that an individual may be receiving, as well as to inform consumers about the potential adverse events associated with a given treatment [22].

Despite these benefits, there are some potential concerns about self-medication, including the potential for consumers to inappropriately use the treatment that is recommended [23]. There is also the concern that some symptoms perceived to be minor may be the result of an undetected more serious condition that was not appropriately identified [23]. It is, therefore, important that undergraduate and postgraduate pharmacist training involves ways of enhancing clinical decision-making skills, which, as indicated by a survey of Canadian pharmacists, are often lacking [24].

Consumers are assuming greater autonomy in their healthcare, which could increase the healthcare system’s efficiency [5]. These emerging trends lend themselves to a greater role for self-care and expanding the role of community pharmacies. In the future, it is most likely pharmacies and pharmacists will not only be providing prescription and non-prescription medications, but will also be involved with more complex interventions. Assisting with self-care and self-medication is essential as the role of the pharmacist continues to evolve to meet the demands of the healthcare system and to ensure they are providing a unique, value-added service.

John Bell, AM, BPharm, FPS, FRPharmS, FACPP, MSHP, Principal Advisor to the Pharmaceutical Society of Australia’s Self-Care Program.

Why Self-Care? A Public Health and Health Economic Perspective on the Benefits of Self-Care

The aging global population [25], increasing incidence and burden of non-communicable diseases (NCDs), and other societal changes (e.g., globalization) [26] have led to increases in healthcare spending [26, 27], which can outpace the growth in gross domestic product [27]. NCDs, including potentially preventable conditions such as cardiovascular disease, respiratory disorders, cancer, and diabetes, are associated with significant disease burden and have become the leading causes of global mortality [26]. Compounding the pressure on the healthcare system, the number of workers per retiree is decreasing, particularly in emerging markets [28].

Traditional healthcare models characterize consumers as limitedly involved, passive recipients, but a shift toward empowering patients and consumers by increasing health literacy to enhance their participation is occurring [5, 29]. Advice from HCPs continues to be an important source of health-related information, but consumers often seek out information on their own, commonly through on-line resources [30], which can increase their ability to recognize symptoms/conditions suitable for self-care. Mobile technologies are becoming increasingly relevant to self-care by offering new consumer education opportunities that can reach into developing countries further and more cost effectively than healthcare infrastructures can [26, 31]. Importantly, consumers who are the most confident in making healthcare decisions have healthcare costs that are 8–21% lower than those who are the least confident [29].

The various stakeholders involved in self-care have complementary roles that must be evaluated from their various perspectives. The pharmaceutical industry is needed to develop safe and effective treatments, to identify appropriate prescription-to-OTC switch candidates, and to educate HCPs and consumers. Governmental agencies are needed to establish appropriate regulations and foster partnerships between HCPs and consumers (e.g., through public health campaigns, enhancing self-care initiatives). Appropriate regulatory frameworks are needed to empower consumers, provide access to safe and effective treatments, promote pharmacists’ roles, and enhance access to OTC products (e.g., by providing tax deductions, switching appropriate treatments from prescription to OTC status). HCPs help consumers recognize symptoms and identify appropriate self-care options, including the use of OTC products. More than 80% of physicians agree that responsible use of OTC products can reduce the burden on the healthcare system and effectively manage minor ailments [32]. Pharmacists have an important role in self-care, particularly self-medication, by serving as a point of access for providing treatment advice or HCP referrals as necessary. In the UK, a study of community pharmacy users seeking care for flu-like symptoms assessed consumer preferences for pharmacy services based on their willingness to pay. Respondents reported a willingness to pay £38 to receive care in a pharmacy setting versus no treatment [33]. However, the quality of care that was provided had an effect on their willingness to pay, as indicated by their unwillingness to pay for care at the lowest-quality pharmacies. The characteristics that differentiated high- from low-quality pharmacies included whether a friendly, trained pharmacy staff member provided a better understanding of the nature of symptoms and how to effectively manage them. Additionally, as has been previously reported, the convenience of accessing the pharmacy was an important factor, as was whether it was local or physician-affiliated versus being located in a shopping center.

Self-care can benefit individuals, healthcare systems, and, as such, society as a whole. The HCP’s role is evolving toward partnering with empowered consumers who are confident in making healthcare decisions. Self-care not only provides an opportunity to relieve overburdened healthcare systems, but also empowers patients and consumers and allows them to more effectively manage their conditions and improve health outcomes and quality of life [5]. Effective use of OTC products can eliminate the stress and inconvenience of HCP visits, saving time and money. In particular, evidence is growing that supports the value OTC products add to the global healthcare system. In addition to reducing costs associated with unnecessary HCP visits, self-care and the use of OTC products can enhance health outcomes and reduce lost work productivity (Table 1) [10, 34]. For example, in the European Union, the estimated annual savings from shifting 5% of care to self-medication is over €16 billion [3]. Although these studies report estimated costs based on hypothetical models, they indicate that there is the potential for substantial healthcare cost savings from enhancing the self-care options that are available to consumers.

Table 1.

Economic benefits of self-care

| United States [34] | Australia [10] | |

|---|---|---|

| Avoided doctors’ visits | 77 billion USD | 3.86 billion AUD |

| Drug costs | 25 billion USD | NA |

| Productivity | 23 billion USD estimated savings in productivity loss | 6.55 billion AUD |

| Total |

102 billion USD For every USD spent on OTC medicines, the US healthcare system saves 6–7 USD in avoided costs |

10.4 billion AUD Over 4 AUD saved per dollar spent |

| Healthcare system | 4 billion USD estimated additional annual savings in avoided emergency department visits | 2.1 billion AUD additional savings if 11 categories of Rx were to be switched to OTC |

AUD Australian dollars, NA not available, OTC over-the-counter, Rx prescription, USD US dollars

Gerald Dziekan, MD, MSc, Director General, World Self-Medication Industry.

Reflux and Heartburn as a Self-Care Model

Heartburn is a common recurrent gastroesophageal symptom marked by a burning sensation that develops behind the sternum and radiates up toward the neck, which may be accompanied by regurgitation of stomach contents (e.g., acid, food) into the mouth [35]. These symptoms most commonly occur after meals, during exercise, and while lying recumbently, particularly at night. Approximately 10–20% of individuals in Western countries experience these symptoms at least weekly, while in Asian countries the prevalence is often less than 5% [36]. The degree of impairment, including symptom frequency and severity, distinguishes frequent heartburn from gastroesophageal reflux disease [36]. However, frequently occurring symptoms of heartburn and regurgitation can negatively impact the affected individual’s quality of life [35].

The World Gastroenterology Organization Global Guidelines for community-based management of common gastrointestinal symptoms provide resource-sensitive treatment recommendations based on the point of care [35]. According to these guidelines, the primary goal for self-treating frequent heartburn is complete symptomatic relief and restoring quality of life. Self-care treatment options for heartburn and/or regurgitation include lifestyle and behavioral modifications such as weight loss and limitations on the consumption of foods/beverages and/or medications that may exacerbate symptoms. OTC treatment options, such as antacids, alginates, H2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs), and PPIs, are also recommended based on the frequency and intensity of heartburn and regurgitation symptoms. Antacids, alginates, and lower- and higher-dose OTC H2RAs are appropriate for infrequent, mild, or moderate symptoms, while OTC PPIs are appropriate for frequent symptoms that occur ≥2 days/week. Regardless of the frequency and intensity of symptoms, all individuals with heartburn should be instructed to include lifestyle/behavioral modifications as adjunctive therapies to these pharmacologic treatments.

A treatment algorithm that was developed for managing individuals presenting in the pharmacy setting with self-diagnosed reflux symptoms describes the circumstances that warrant referral to a physician [37]. Individuals presenting with alarm features, including new symptom onset at over 50 years of age, painful or difficult swallowing, gastrointestinal bleeding, laryngitis, unexplained weight loss, and cardiac-type chest pain, should be referred to a physician [35, 37]. Additionally, individuals who do not adequately respond to a 2-week course of OTC PPI therapy and those who experience a recurrence of symptoms within 3 months of stopping a 2-week course of OTC PPI therapy should be referred.

The relatively high prevalence of uncomplicated frequent heartburn and the availability of highly effective OTC treatment options make managing these symptoms in a physician’s office inefficient in terms of cost and resource utilization [37]. Pharmacists are, therefore, ideally positioned to serve as frontline HCPs with an important role in identifying consumers who are suitable for self-treating their heartburn. Additionally, pharmacists can reinforce directions provided by the product labelling and communicate that a failure to respond to treatment requires a physician consultation. Frequent heartburn has few direct long-term consequences, but it is important to identify those with a high likelihood of having a serious underlying condition to manage these symptoms effectively and safely [35, 37]. Additionally, although there are potential safety concerns associated with the long-term use of PPIs, instances are rare in this population and most individuals experiencing frequent heartburn will not require extended periods of treatment [35, 37].

Varocha Mahachai, MD, FRCP, Director, GI & Liver Center, Bangkok Medical Center, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand.

Conclusion

Shifting care for certain conditions from physicians to other HCPs, including pharmacists, and consumers can help to alleviate the increasing burden on the healthcare system by reducing costs and resource utilization. Self-care and self-medication are expected to be important aspects of the evolving global healthcare system that will seek to manage these issues.

Self-care functions most efficiently when the various stakeholders collaborate to serve consumers’ needs by providing appropriate guidance and empowering their decision-making processes. Pharmacists, therefore, play a critical role in helping consumers manage minor ailments without relying on costly and time-consuming physician visits for conditions that can be self-managed. Additional stakeholders, including the pharmaceutical industry and governmental agencies, help to ensure that safe and effective self-care treatment options are available.

Heartburn and regurgitation is a prime example of a generally mild condition that is ideal for self-care. Lifestyle modifications and numerous OTC treatment options are available that have been shown to be safe and effective. Pharmacists can be expected to play a key role in educating consumers about the proper use of these products, including, for instance, following label instructions and consulting a physician if symptoms recur at the end of the assigned treatment period or if other alarm features appear.

Acknowledgments

John Bell would like to thank John Chave, MA, for his contributions to the content in Mr. Bell’s section. Sponsorship, article processing charges, and the open access charge for this article were funded by Pfizer Inc. Medical writing support was provided by Dennis Stancavish at Peloton Advantage, LLC, and was funded by Pfizer Inc. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval to the version to be published.

Disclosures

John Bell is a member of the Global Respiratory Infection Partnership. He has acted as a consultant to Pfizer Consumer Healthcare. Gerald Dziekan is an employee of the World Self-Medication Industry. Varocha Mahachai has no conflicts to disclose. Charles Pollack is an employee of Pfizer Consumer Healthcare.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Footnotes

Enhanced content

To view enhanced content for this article go to http://www.medengine.com/Redeem/9AE4F06044A0FCF4.

References

- 1.What do we mean by self care and why is it good for people? The self-care continuum. Self Care Forum web site. http://www.selfcareforum.org/about-us/what-do-we-mean-by-self-care-and-why-is-good-for-people/. Accessed June 16, 2016.

- 2.Nonprescription Medicines Academy mission statement. Nonprescription Medicines Academy. http://www.nmafaculty.org/about-nma. Accessed June 16, 2016.

- 3.Self-care: a winning solution. Association of the European Self-Medication Industry. http://www.aesgp.eu/media/cms_page_media/68/Self-Care%20A%20Winning%20Solution.pdf. Accessed June 16, 2016.

- 4.Self-care in the context of primary health care. World Health Organization; 2009. http://www.searo.who.int/entity/primary_health_care/documents/sea_hsd_320.pdf. Accessed June 16, 2016.

- 5.The Epposi Barometer . Consumer perceptions of self care in Europe. Quantitative Study 2013. Brussels: Epposi; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Webber D, Guo Z, Mann S. Self-care in health: we can define it, but should we also measure it? SelfCare. 2013;4(5):101–106. [Google Scholar]

- 7.What we know about…health literacy. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2009. http://www.cdc.gov/healthcommunication/pdf/audience/healthliteracy.pdf. Accessed June 16 2016.

- 8.Health literacy, Australia: summary of findings. Australian Bureau of Statistics; 2006. http://abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/Latestproducts/4233.0Main%20Features22006?opendocument&tabname=Summary&prodno=4233.0&issue=2006&num=&view=. Accessed June 8, 2016.

- 9.Vernon JA, Trujillo A, Rosenbaum S, DeBuono B. Low health literacy: implications for national health policy. World Education; 2007. http://publichealth.gwu.edu/departments/healthpolicy/CHPR/downloads/LowHealthLiteracyReport10_4_07.pdf. Accessed June 16, 2016.

- 10.The value of OTC medicines in Australia. World Self-Medication Industry; 2014. http://www.wsmi.org/wp-content/data/pdf/FINALWEBCOPYASMI_ValueStudy.pdf. Accessed June 16, 2016.

- 11.Pharmacists and Primary Health Care Consumer Survey . Results and discussion. Barton: Consumers Health Forum of Australia; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 12.The role of the pharmacist in self-care and self-medication. World Health Organization; 1998. http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/pdf/whozip32e/whozip32e.pdf. Accessed May 25, 2016.

- 13.Roberts A (2014) A real health destination [online]. Australian Pharmacist 33(1):28–29.http://search.informit.com.au/documentSummary;dn=049195174537379;res=IELAPA

- 14.Global Respiratory Infection Partnership. Antibiotic resistance: prioritising the patient. Report from the Global Respiratory Infection Partnership; 2015. http://www.grip-initiative.org/media/114428/recstr-grip-cta-meeting-report.pdf. Accessed June 16, 2016.

- 15.Fielding S, Porteous T, Ferguson J, Maskrey V, Blyth A, Paudyal V, et al. Estimating the burden of minor ailment consultations in general practices and emergency departments through retrospective review of routine data in North East Scotland. Fam Pract. 2015;32(2):165–172. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmv003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.PGEU Annual Report 2014. Promoting efficiency, improving lives. PGEU; 2015. http://www.pgeu.eu/en/component/content/article/34-homepage-topics/16-pgeu-annual-report.html. Accessed June 16, 2016.

- 17.Towards responsible self care: the role of health literacy, pharmacy and non-prescription medicines. Global Access Partners; 2015. http://www.globalaccesspartners.org/GAP_Taskforce_on_Self_Care_Report_released_23_June_2015.pdf. Accessed June 16, 2016.

- 18.The changing landscape—a multi-country study undertaken with AESGP. Nielsen Company; 2009. http://www.selfcareforum.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/07/AESGPResearchJun09.pdf. Accessed June 16, 2016.

- 19.Dwyer F. Driving the self care agenda: minor ailment workload in general practice. Australian Self Medication Industry Web Site; 2008. http://www.asmi.com.au/documents/Fabian%20Dwyer2008.pdf. Accessed June 16, 2016.

- 20.Watson MC, Ferguson J, Barton GR, Maskrey V, Blyth A, Paudyal V, et al. A cohort study of influences, health outcomes and costs of patients’ health-seeking behaviour for minor ailments from primary and emergency care settings. BMJ Open. 2015;5(2):e006261. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paudyal V, Hansford D, Cunningham S, Stewart D. Pharmacy assisted patient self care of minor ailments: a chronological review of UK health policy documents and key events 1997–2010. Health Policy. 2011;101(3):253–259. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.SWITCH Prescription to nonprescription medicines switch. World Self-Medication Industry; 2009. http://www.wsmi.org/wp-content/data/pdf/wsmi_switchbrochure.pdf. Accessed June 16, 2016.

- 23.Report of the working group on promoting good governance of non-prescription drugs in Europe. European Commission; 2013. http://ec.europa.eu/DocsRoom/documents/7623?locale=en. Accessed June 16, 2016.

- 24.Frankel GE, Austin Z. Responsibility and confidence: identifying barriers to advanced pharmacy practice. Can Pharm J (Ott). 2013;146(3):155–161. doi: 10.1177/1715163513487309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Health at a glance 2011: OECD indicators. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2011.

- 26.Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2014. World Health Organization; 2014. http://www.who.int/nmh/publications/ncd-status-report-2014/en/. Accessed June 16, 2016.

- 27.Drouin JP, Hediger V, Henke N. Health care costs: a market-based view. McKinsey Quarterly. 2008:1–11.

- 28.The world at work: jobs, pay, and skills for 3.5 billion people. McKinsey Global Institute; 2012. http://www.mckinsey.com/insights/employment_and_growth/the_world_at_work. Accessed June 16, 2016.

- 29.Health policy brief: patient engagement. Health Affairs; 2013. http://www.healthaffairs.org/healthpolicybriefs/brief.php?brief_id=86. Accessed June 16, 2016.

- 30.Fox S, Duggan M. Health online 2013. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center’s Internet and American Life Project; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Consulting VW. mHealth for development: the opportunity of mobile technology for healthcare in the developing World. Washington, DC: UN Foundation-Vodafone Foundation Partnership; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Your health at hand: perceptions of over-the-counter medicine in the US Consumer Healthcare Products Association; 2010. http://www.yourhealthathand.org/images/uploads/CHPA_YHH_Survey_062011.pdf. Accessed June 16, 2016.

- 33.Porteous T, Ryan M, Bond C, Watson M, Watson V. Managing minor ailments; the public's preferences for attributes of community pharmacies. A discrete choice experiment. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0152257. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.The value of OTC medicine to the United States. yourhealthathand.org; 2012. http://www.yourhealthathand.org/images/uploads/The_Value_of_OTC_Medicine_to_the_United_States_BoozCo.pdf. Accessed June 16, 2016.

- 35.Coping with common GI symptoms in the community: a global perspective on heartburn, constipation, bloating, and abdominal pain/discomfort. World Gastroenterology Organisation; 2013. http://www.worldgastroenterology.org/assets/export/userfiles/2013_FINAL_Common%20GI%20Symptoms%20_long.pdf. Accessed May 25, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Dent J, El-Serag HB, Wallander MA, Johansson S. Epidemiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Gut. 2005;54(5):710–717. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.051821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boardman HF, Delaney BC, Haag S. Partnership in optimizing management of reflux symptoms: a treatment algorithm for over-the-counter proton-pump inhibitors. Curr Med Res Opin. 2015;31(7):1309–1318. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2015.1047745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]