Abstract

Introduction

Misperceptions about ulcerative colitis (UC) may influence management strategies and limit opportunities for improving patient outcomes. This study assessed physicians’ perceptions of UC, concepts of disease severity and remission, and treatment goals.

Methods

Gastroenterologists who typically treated ≥10 adults with UC per month were recruited for a large-scale, web-based survey. Participants were asked about their perceptions of UC (often vs. Crohn’s disease [CD]), treatment goals, and medication use. Response data were evaluated via descriptive statistics and univariate and multivariable analyses.

Results

Gastroenterologists (N = 500) with a mean of 16.5 years (standard deviation, 8.7 years) in practice participated. In comparison to CD, survey respondents perceived UC as being easier to diagnose, having better treatment outcomes, and being associated with later prescribing of biologics. Treatment goals commonly considered to have the greatest importance included quality of life improvement (31.2% of respondents), maintenance of clinical remission (17.4%), and mucosal healing (17.4%). When respondents evaluated the performance of medication classes in achieving these goals, biologics were rated significantly higher than all other classes (P < 0.05). However, the most common drivers for the initiation of biologic therapy were the development of steroid refractoriness (66.8%) and steroid dependency (65.8%). Medication class use by UC severity was generally consistent with the traditional step-up approach to UC therapy, with biologics being used most commonly for severe UC.

Conclusion

These results suggest a possible disparity between treatment goals and therapeutic management in UC. An increased awareness of general UC perceptions is an important step toward a better overall understanding of the disease and, ultimately, toward improved management aligned with treatment goals.

Funding

This study was sponsored by the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA), and the design and conduct of the study as well as article processing charges and the open access fee for this publication were funded by Takeda Pharmaceuticals International, Inc. (TPI).

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s12325-016-0393-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: 5-Aminosalicylic agents, Antibiotics, Biologics, Corticosteroids, Gastroenterology, Immunomodulators, Inflammatory bowel disease

Introduction

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease that is characterized by abdominal pain, recurrent episodes of rectal bleeding, and greater-than-normal stool frequency [1, 2]. In the United States (US), the estimated prevalence of UC is 263 per 100,000 adults, and epidemiologic data suggest that the disease has become increasingly prevalent during the past decade [3]. Although slightly more than half of patients with UC have high initial disease activity followed by remission or mild disease severity, >40% of patients may have chronic continuous or intermittent symptoms of high disease activity [4]. Progression of UC may include proximal extension of the disease, colonic dysmotility, anorectal dysfunction, and an increased risk of colorectal cancer [5, 6]. The disease may adversely affect patients’ daily activities and quality of life (QoL), and patients with UC have higher rates of sick leave and disability than do individuals in the general population [2, 7].

A variety of misperceptions about UC may influence management strategies and limit opportunities for improving patient outcomes; for example, UC is commonly regarded as more benign than Crohn’s disease (CD) [1]. However, despite continuing advances in the treatment of UC, approximately half of patients do not achieve sustained clinical remission [1], and approximately 15% of patients undergo a colectomy within 20 years after UC diagnosis [8]. Although colectomy is widely seen as a definitive treatment option for UC, the procedure often leads to complications, such as acute or chronic pouchitis or the risk of infertility [1, 9]. Results from a recent systematic review of 99 studies (conducted between 1976 and 2014 and involving >180,000 patients) suggest that approximately one-third of patients who undergo colorectal surgery for UC have long-term or late-occurring complications [9].

In this study, we aimed to assess gastroenterologists’ attitudes toward and perceptions of UC via a small-scale qualitative phone survey followed by a large-scale, quantitative web-based survey.

Methods

This survey study was in accordance with the ethical standards of an institutional review board and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964, as revised in 2013, and consisted of two phases. Phase 1 was a small-scale phone survey, results of which have been reported previously (Table S1 in the supplementary material) [10] and were used in the development of the phase 2 survey. The phase 2 survey was a large-scale web-based survey of gastroenterologists who provided informed consent and received an honorarium of $75.00 for being included in the study and were members of the All Global physician panel, an actively managed, double opt-in group of physicians who elect to participate in periodic surveys. All US members of the All Global panel were verified using the American Medical Association database. A total of 15,000 US gastroenterologists from the panel were invited via e-mail to participate. Key inclusion criteria stipulated that participants be board certified in and have a primary specialty of gastroenterology; spend ≥50% of their professional time on direct patient care; spend ≥50% of their professional time in a private practice, clinic, or hospital setting; and treat ≥10 adults with UC per month.

The survey included questions regarding several aspects of UC and its treatment (see online supplementary material for the complete survey). To assess perceptions of UC vs. CD, gastroenterologists were asked to rate their level of agreement with each of four statements on a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Survey participants then rated 11 additional statements in terms of their association with UC or CD (scale: 1, most associated with UC; 4, equally associated with UC and CD; 7, most associated with CD). To evaluate factors used in distinguishing mild from moderate UC, participants selected their top five choices from a list of 17 factors. In addition, respondents were asked to choose any and all items (from a list of 10) that they considered to be defining features of clinical remission in UC.

Given a list of 10 potential treatment goals for UC, participants first rated each goal on a scale of 1 (extremely unimportant) to 7 (extremely important) and then ranked these goals in order of their importance, with 1 being the most important. Respondents also rated the performance of four medication classes (5-aminosalicylic acid [ASA] agents, corticosteroids, immunomodulators, and biologics/anti-tumor necrosis factor agents) in achieving each treatment goal using a scale of 1 (very poor) to 5 (very well).

Participants rated the frequency with which they used each medication class (1, never; 5, always) as induction and maintenance therapies for patients with mild, moderate, and severe UC. In addition, for each medication class, respondents indicated the number of weeks that patients with mild, moderate, and severe UC remained on the treatment before it was deemed successful or not. To assess drivers for the initiation of biologic therapy, respondents were asked to select up to five statements (from a list of 17) that might prompt them to prescribe biologic therapy. Finally, participants were asked if they experienced barriers to the use of biologic therapies, and those who answered yes were asked to select all that applied from a list of 12 potential barriers.

All survey responses were summarized with descriptive statistics. Single-sample t tests were used to analyze responses to questions about whether statements are more indicative of UC or CD. The frequency at which each type of treatment was used as induction and maintenance therapies was analyzed using a mixed model, and a similar mixed model was used to assess differences in attribute agreement across treatments. A final mixed model was used to analyze differences with respect to the necessary duration of treatment before success (or lack thereof) could be established. All tests of significance were two-tailed.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Participants (N = 500) in the phase 2 survey were predominantly male gastroenterologists between the ages of 35 and 64 years (Table 1). More than half of respondents were part of a private group practice, and the average time in practice was 16.5 years. Participants reported spending the vast majority of their time on direct patient care, seeing >300 patients per month on average.

Table 1.

The phase 2 survey participant characteristics (N = 500)

| Characteristic | |

|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 441 (88.2) |

| Female | 48 (9.6) |

| Not stated | 11 (2.2) |

| Age, years, n (%) | |

| <35 | 29 (5.8) |

| 35–44 | 152 (30.4) |

| 45–54 | 140 (28.0) |

| 55–64 | 135 (27.0) |

| ≥65 | 32 (6.4) |

| Not stated | 12 (2.4) |

| Practice type, n (%) | |

| Solo | 73 (14.6) |

| Single-specialty group | 250 (50.0) |

| Multispecialty group | 177 (35.4) |

| Years in practice, mean (SD) | 16.50 (8.73) |

| Percentage of time allocation, mean (SD) | |

| Direct patient care | 92.54 (10.00) |

| Teaching | 3.24 (5.37) |

| Conducting research | 1.97 (5.38) |

| Administration | 2.17 (3.69) |

| Other activities | 0.08 (1.03) |

| Type of setting for patient care, n (%) | |

| Hospital (nonteaching/academic) | 15 (3.0) |

| Hospital (teaching/academic) | 122 (24.4) |

| Clinic | 23 (4.6) |

| Private group practice | 282 (56.4) |

| Private solo practice | 58 (11.6) |

| Number of adult patients per month, mean (SD) | 317.5 (146.3) |

| Diagnosis of adult patients, mean (SD), % of patients | |

| UC | 17.7 (14.7) |

| CD | 17.2 (15.1) |

| Other, non-IBD | 60.6 (29.4) |

| UC severity, mean (SD), % of patients | |

| Mild | 41.6 (19.9) |

| Moderate | 38.4 (14.7) |

| Severe | 19.95 (12.13) |

| CD severity, mean (SD), % of patients | |

| Mild | 37.2 (20.0) |

| Moderate | 40.7 (15.4) |

| Severe | 22.2 (12.7) |

CD Crohn’s disease, IBD inflammatory bowel disease, SD standard deviation, UC ulcerative colitis

Perceptions of UC vs. CD

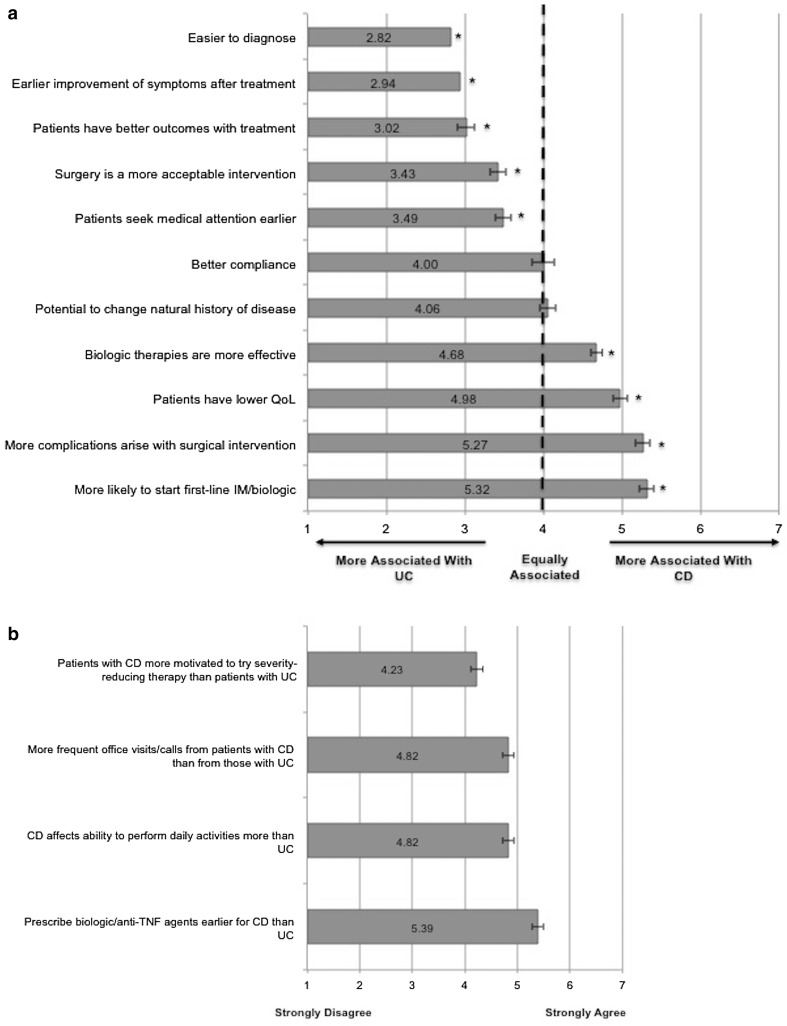

Compared with CD, UC was perceived as easier to diagnose and having better treatment outcomes (Fig. 1a). Survey respondents prescribed biologics earlier for CD than for UC. CD was perceived as having a greater effect than UC on patients’ ability to perform daily activities (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

a Association of statements with UC or CD. Rated on a continuous scale from 1 to 7; lower scores indicate a greater association with UC; the dotted line indicates an equal association between UC and CD; and higher scores indicate a greater association with CD. b Participant agreement with UC- and CD-related statements. *P < 0.05. Bars represent means; and error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. CD Crohn’s disease, IM immunomodulatory, QoL quality of life, TNF tumor necrosis factor, and UC ulcerative colitis

Determining UC Severity

Factors that physicians most commonly used to distinguish between mild and moderate UC included number of stools per day above normal, ulcerations on endoscopy, and rectal bleeding, each cited by >50% of respondents (Table 2). Less commonly cited factors (cited by <50% but >20% of respondents) were anemia, impact on QoL, weight loss, hospitalizations per year, abdominal pain, nocturnal bowel movements, friability on endoscopy, and fever.

Table 2.

Factors used by gastroenterologists to distinguish mild from moderate UC (N = 500)

| Response | Number (%) of participants citing |

|---|---|

| Number of stools per day above normal | 306 (61.2) |

| Ulcerations on endoscopy | 278 (55.6) |

| Rectal bleeding | 272 (54.4) |

| Anemia | 211 (42.2) |

| Impact on QoL | 182 (36.4) |

| Weight loss | 174 (34.8) |

| Hospitalizations per year | 169 (33.8) |

| Abdominal pain | 166 (33.2) |

| Nocturnal bowel movements | 160 (32.0) |

| Friability on endoscopy | 118 (23.6) |

| Fever | 117 (23.4) |

| Tenesmus | 89 (17.8) |

| Urgency | 79 (15.8) |

| Spontaneous bleeding on endoscopy | 71 (14.2) |

| Tachycardia | 48 (9.6) |

| Fecal incontinence | 31 (6.2) |

| Fecal calprotectin level | 29 (5.8) |

QoL quality of life, UC ulcerative colitis

The top factors used to distinguish mild from moderate UC were also examined on the basis of various practitioner characteristics. No significant differences based on gender, practice setting (private vs. public/other), or practice type (group vs. solo) were noted. However, gastroenterologists aged ≤44 years cited ulcerations on endoscopy as a top factor significantly more often than did those aged ≥45 years (data not shown).

Defining Clinical Remission in UC

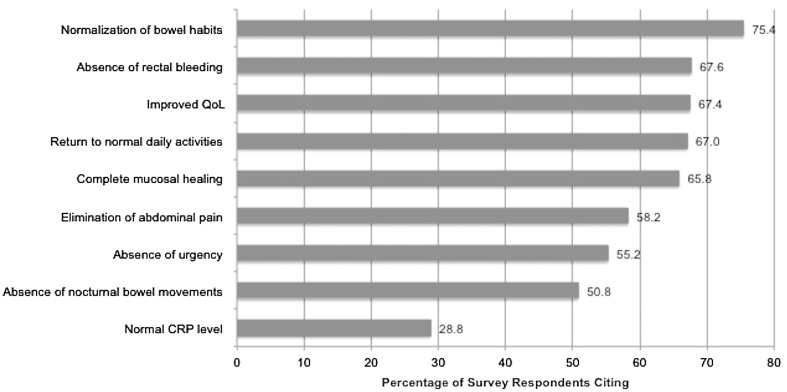

Improved QoL was among the most often cited defining features of clinical remission, along with normalization of bowel habits, absence of rectal bleeding, return to normal daily activities, and complete mucosal healing (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Defining features of clinical remission among patients with UC, as reported by gastroenterologists (N = 500). CRP C-reactive protein, QoL quality of life, and UC ulcerative colitis

UC Treatment Goals and Medication Performance Ratings

Treatment goals that were commonly considered most important by the survey participants included QoL improvement (31.2% of respondents), maintenance of clinical remission (17.4%), and mucosal healing (17.4%). When respondents rated the performance of each medication class in achieving each of these treatment goals, biologics had significantly higher ratings than all other classes (P < 0.05), whereas 5-ASA agents commonly had the lowest ratings (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Performance ratings of medication classes by UC treatment goals. Scale 1 very poor; 5 very well. Letters A, B, C, and D indicate which medication groups were significantly different from others for each attribute (P < 0.05, a Tukey post hoc adjustment). Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Asterisk indicates not applicable. ASA aminosalicylic acid, QoL quality of life, and UC ulcerative colitis

Medication Use by UC Severity

Medication class use by severity of UC was generally consistent with the traditional step-up approach to UC therapy [11–13]. For mild and moderate UC, 5-ASA agents were employed significantly more often than any other class (P < 0.05), regardless of whether they were used for induction or maintenance. For severe UC, corticosteroids were used more often for induction, and biologics were used more often for maintenance than any other medication class (P < 0.05 for both). Unlike use of other medication classes, the use of 5-ASA agents decreased with increased UC severity (P < 0.05 for use in mild vs. moderate, mild vs. severe, and moderate vs. severe UC). However, somewhat unexpectedly, the mean frequency rating for 5-ASA agent use was high for severe UC (induction, 3.06 [95% confidence interval (CI), 2.97–3.14]; maintenance, 3.36 [95% CI, 3.27–3.44]). For some medication classes, the frequency of use in mild, moderate, and severe UC differed significantly depending on the characteristics of the treating gastroenterologist, including gender, age, practice setting, and practice type (Tables S2 and S3 in the supplementary material).

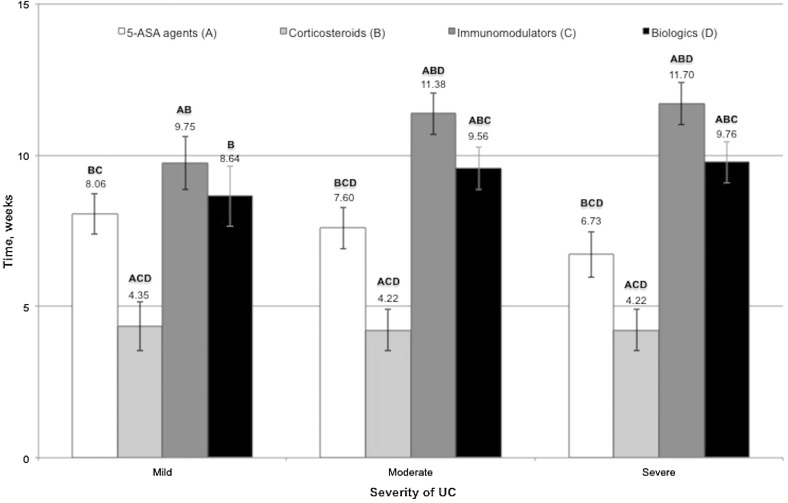

Duration of Treatment by Medication Class

Corticosteroids required the shortest duration of use before treatment success (or lack thereof) was determined; immunomodulators required the longest duration (Fig. 4). The mean duration of 5-ASA use before treatment was deemed unsuccessful was significantly shorter for severe UC than for mild UC (P < 0.05). Conversely, the mean duration of immunomodulator use before establishment of treatment success/lack of success was significantly longer for moderate and severe UC than for mild UC (P < 0.05). For corticosteroids and biologics, the duration of use before treatment success designation was similar across mild, moderate, and severe UC.

Fig. 4.

Time (weeks) a patient with UC must receive therapy before it is deemed successful or not by medication class. Bars represent mean values. Letters A, B, C, and D indicate which medication classes were significantly different from other classes within each level of UC severity (P < 0.05 using a Tukey post hoc adjustment). Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. ASA aminosalicylic acid and UC ulcerative colitis

Drivers for Use of Biologic Therapy

The most common drivers for initiation of biologic therapy in patients with moderate-to-severe UC included the development of steroid refractoriness (66.8%) and steroid dependency (65.8%), increases in the number of hospitalizations for UC (62.2%), and decreases in patients’ ability to perform daily activities (56.0%). Laboratory measures, including C-reactive protein levels, were not strong drivers for initiation of biologic therapy.

Barriers to Use of Biologic Therapy

Of the 500 survey respondents, 219 (43.8%) reported that they have experienced barriers to prescribing biologics for UC. The most commonly cited barriers included patient insurance restrictions (79.0%), out-of-pocket cost for patients (71.7%), and patient and physician concerns about side effects (57.1% and 50.7%, respectively).

Discussion

These survey results highlight common perceptions among practicing physicians, including the idea that UC is relatively benign and less burdensome and easier to diagnose and treat than CD. However, results from other recent surveys suggest that despite treatment, many patients feel that UC disrupts their lives and relationships and is associated with substantial physical and psychological burdens [14–17]. Compared with patients, gastroenterologists who treat UC may underestimate the physical and psychological impacts of the disease as well as the disruptive effects of symptoms on day-to-day life while simultaneously overestimating disease control [18]. In addition, findings from a recent French survey study suggest that treatment with anti-tumor necrosis factor agents was significantly less common in patients with UC than in those with CD and that despite recent increases in available biologic treatment options, disease activity persists in many patients [19].

The perceptions about UC highlighted herein may ultimately lead to suboptimal management approaches. In the current survey, UC steroid refractoriness and steroid dependency were the most commonly cited drivers for the initiation of biologic therapy, which implies that biologics are used relatively late in the disease course, consistent with the traditional step-up approach to therapy. Meanwhile, the recent literature suggests that treatment goals and therapeutic approaches for UC are evolving [11, 13, 20–23]. The premise behind earlier use of more potent therapies is the potential for rapid induction of steroid-free remission and promotion of mucosal healing, which may modify the natural history of UC [23].

As an alternative approach, some authors have suggested that structured treatment algorithms with specific time limits for evaluation of therapeutic success would be useful in guiding therapeutic decisions and achieving treatment goals [23]. The recently published Ulcerative Colitis Care Pathway considers not only disease activity but also risk stratification to provide a pragmatic management tool for clinicians [24]. Treat-to-target strategies have also emerged, wherein treatment algorithms are geared toward a specific, well-defined target or targets, such as mucosal healing, histologic healing, or deep remission [11, 13, 21, 25]. In cases where a link between the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic effects of a biologic agent has been well established, therapeutic drug monitoring with dosage adjustment to achieve a serum trough drug concentration target helps to improve outcomes and reduce costs [13, 21, 25]. Furthermore, assessment for the presence of anti-drug antibodies along with drug concentration monitoring could help guide treatment decisions [13, 26].

Several limitations of this study should be noted. First, as in any survey study and particularly in the context of honoraria provided for survey completion, the physician-reported data described herein may have been affected by recall bias, and there was no independent confirmation of data (e.g., frequency of medication use) from medical records. Survey participants may also have had characteristics that differ from those who chose not to participate; thus, results may not be generalizable to the overall gastroenterology population. In addition, the survey did not include questions about certain practice dynamics (e.g., typical frequency and duration of appointments, involvement of nurse practitioners or physician assistants in patients’ care), which could have yielded useful insight on perceptions of UC. Finally, the survey did not allow participants to specify whether medications were used as monotherapy or as part of polytherapy, thus hindering the interpretation of medication use and duration of use data.

Despite these limitations, this study had numerous strengths, including its 2-phase design, wherein results from a small preliminary phone survey were used to inform the development of the large-scale, web-based phase 2 survey described here. Survey participants were 500 experienced and currently practicing gastroenterologists who treat at least 10 patients with UC per month on average and spend >50% of their professional time on direct patient care. Thus, these data represent a robust sample of physicians with extensive clinical experience in treating patients with UC.

The current survey study provides valuable information regarding UC from the perspective of gastroenterologists. Clinicians’ perceptions of UC may influence their treatment goals and therapeutic decisions, possibly limiting opportunities for better outcomes with earlier use of therapies that may be effective. An increased awareness of such perceptions is an important step toward a better overall understanding of UC and, ultimately, toward improved management aligned with treatment goals.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

This study was sponsored by the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA), and the design and conduct of the study as well as article processing charges and the open access fee for this publication were funded by Takeda Pharmaceuticals International, Inc. (TPI). All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval to the version to be published, including the authorship list. Karen Lasch, Stephen Liu, Lyann Ursos, and Reema Mody contributed to study concept and design; acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation of data; drafting of the manuscript; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; statistical analysis; obtainment of funding; administrative, technical, or material support; and study supervision. Kristen King-Concialdi contributed to study concept and design; acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation of data; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; administrative, technical, or material support; and study supervision. Marco DiBonaventura contributed to study concept and design; acquisition of data; statistical analysis; analysis and interpretation of data; and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. Julie Leberman contributed to study concept and design; acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation of data; drafting of the manuscript; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; statistical analysis; obtainment of funding; administrative, technical, or material support; and study supervision. Marla Dubinsky will act as the guarantor of the article; she contributed to study concept and design; acquisition of data; analysis and interpretation of data; drafting of the manuscript; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; statistical analysis; obtainment of funding; administrative, technical, or material support; and study supervision. Medical writing support and editorial assistance in the preparation of this manuscript was provided by Elizabeth Barton of MedLogix Communications, LLC, and was funded by TPI.

Disclosures

Karen Lasch, Stephen Liu, and Lyann Ursos are employees of Takeda Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc. Reema Mody was an employee of Takeda Pharmaceuticals International, Inc., at the time of the study and is currently an employee of Eli Lilly and Company. Kristen King-Concialdi, Marco DiBonaventura, and Julie Leberman have served as consultants for Takeda Pharmaceuticals International, Inc. Marla Dubinsky has served as a consultant for Takeda Pharmaceuticals International, Inc.; AbbVie Inc.; Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Pfizer; Prometheus; UCB Pharma; and Celgene.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964, as revised in 2013. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Footnotes

Enhanced content

To view enhanced content for this article go to http://www.medengine.com/Redeem/E9E4F0602AD975D5.

References

- 1.Ochsenkühn T, D’Haens G. Current misunderstandings in the management of ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2011;60:1294–1299. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.218180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernklev T, Jahnsen J, Henriksen M, Lygren I, Aadland E, Sauar J, et al. Relationship between sick leave, unemployment, disability, and health-related quality of life in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:402–412. doi: 10.1097/01.MIB.0000218762.61217.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kappelman MD, Moore KR, Allen JK, Cook SF. Recent trends in the prevalence of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in a commercially insured US population. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:519–525. doi: 10.1007/s10620-012-2371-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Solberg IC, Lygren I, Jahnsen J, Aadland E, Hoie O, Cvancarova M, et al. Clinical course during the first 10 years of ulcerative colitis: results from a population-based inception cohort (IBSEN Study) Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:431–440. doi: 10.1080/00365520802600961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lutgens MW, van Oijen MG, van der Heijden GJ, Vleggaar FP, Siersema PD, Oldenburg B. Declining risk of colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: an updated meta-analysis of population-based cohort studies. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:789–799. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0b013e31828029c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Torres J, Billioud V, Sachar DB, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Colombel JF. Ulcerative colitis as a progressive disease: the forgotten evidence. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:1356–1363. doi: 10.1002/ibd.22839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Høivik ML, Moum B, Solberg IC, Henriksen M, Cvancarova M, Bernklev T, et al. Work disability in inflammatory bowel disease patients 10 years after disease onset: results from the IBSEN Study. Gut. 2013;62:368–375. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Targownik LE, Singh H, Nugent Z, Bernstein CN. The epidemiology of colectomy in ulcerative colitis: results from a population-based cohort. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1228–1235. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peyrin-Biroulet L, Patel AS, Lindsay JO. Colectomy is not a cure for ulcerative colitis: a systematic review (P403). https://www.ecco-ibd.eu/index.php/publications/congress-abstract-s/abstracts-2015/item/p403-colectomy-is-not-a-cure-for-ulcerative-colitis-a-systematic-review.html. Accessed March 5, 2015.

- 10.Lasch K, Ursos L, Liu S, Mody R, Concialdi K, DiBonaventura M, et al. Understanding attitudes, perceptions, and beliefs about ulcerative colitis among gastroenterologists: phase 1 survey results (abstract 1631) Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:S484. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.52. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones J, Peña-Sánchez JN. Who should receive biologic therapy for IBD? The rationale for the application of a personalized approach. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2014;43:425–440. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2014.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kornbluth A, Sachar DB, Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology Ulcerative colitis practice guidelines in adults: American College of Gastroenterology, Practice Parameters Committee. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:501–523. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Samaan MA, Bagi P, Vande Casteele N, D’Haens GR, Levesque BG. An update on anti-TNF agents in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2014;43:479–494. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2014.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rubin DT, Dubinsky MC, Panaccione R, Siegel CA, Binion DG, Kane SV, et al. The impact of ulcerative colitis on patients’ lives compared to other chronic diseases: a patient survey. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:1044–1052. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-0953-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hofmann R, Guillaume X. Current views and concerns of European UC patients based on an online survey (P690). https://www.ecco-ibd.eu/index.php/publications/congress-abstract-s/abstracts-2015/item/p690-current-views-and-concerns-of-european-uc-patients-based-on-an-online-survey.html. Accessed March 5, 2015.

- 16.Carpio D, Argüelles F, Calvet X, Juliá B, Romero C, López-Sanromán A. Perception of social and emotional impact of ulcerative colitis by Spanish patients—UC-life survey (P645). https://www.ecco-ibd.eu/index.php/publications/congress-abstract-s/abstracts-2015/item/p645-perception-of-social-and-emotional-impact-of-ulcerative-colitis-by-spanish-patients-uc-life-survey.html. Accessed March 5, 2015.

- 17.López-Sanromán A, Carpio D, Calvet X, Cea-Calvo L, Romero C, Argüelles F. Perception about disease activity and treatment attributes in patients with ulcerative colitis from Spain—UC-life survey (P670). https://www.ecco-ibd.eu/index.php/publications/congress-abstract-s/abstracts-2015/item/p670-perception-about-disease-activity-and-treatment-attributes-in-patients-with-ulcerative-colitis-from-spain-uc-life-survey.html. Accessed March 5, 2015.

- 18.Rubin DT, Siegel CA, Kane SV, Binion DG, Panaccione R, Dubinsky MC, et al. Impact of ulcerative colitis from patients’ and physicians’ perspectives: results from the UC: NORMAL survey. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:581–588. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duchesne C, Faure P, Kohler F, Pingannaud MP, Bonnaud G, Devulder F, et al. Management of inflammatory bowel disease in France: a nationwide survey among private gastroenterologists. Dig Liver Dis. 2014;46:675–681. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2014.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.D’Haens GR, Sartor RB, Silverberg MS, Petersson J, Rutgeerts P. Future directions in inflammatory bowel disease management. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:726–734. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2014.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levesque BG, Sandborn WJ, Ruel J, Feagan BG, Sands BE, Colombel JF. Converging goals of treatment of inflammatory bowel disease from clinical trials and practice. Gastroenterology. 2015;148(37–51):e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burger D, Travis S. Conventional medical management of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2011;140(1827–37):e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.02.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Panaccione R, Rutgeerts P, Sandborn WJ, Feagan B, Schreiber S, Ghosh S. Treatment algorithms to maximize remission and minimize corticosteroid dependence in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28:674–688. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03753.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dassopoulos T, Cohen RD, Scherl EJ, Schwartz RM, Kosinski L, Regueiro MD. Ulcerative colitis care pathway. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:238–245. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gerich ME, McGovern DP. Towards personalized care in IBD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;11:287–299. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Afif W, Loftus EV, Jr, Faubion WA, Kane SV, Bruining DH, Hanson KA, et al. Clinical utility of measuring infliximab and human anti-chimeric antibody concentrations in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1133–1139. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.