Abstract

Echinococcus granulosus (E. granulosus) and Echinococcus multilocularis (E. multilocularis) infections are the most common parasitic diseases that affect the liver. The disease course is typically slow and the patients tend to remain asymptomatic for many years. Often the diagnosis is incidental. Right upper quadrant abdominal pain, hepatitis, cholangitis, and anaphylaxis due to dissemination of the cyst are the main presenting symptoms. Ultrasonography is important in diagnosis. The World Health Organization classification, based on ultrasonographic findings, is used for staging of the disease and treatment selection. In addition to the imaging methods, immunological investigations are used to support the diagnosis. The available treatment options for E. granulosus infection include open surgery, percutaneous interventions, and pharmacotherapy. Aggressive surgery is the first-choice treatment for E. multilocularis infection, while pharmacotherapy is used as an adjunct to surgery. Due to a paucity of clinical studies, empirical evidence on the treatment of E. granulosus and E. multilocularis infections is largely lacking; there are no prominent and widely accepted clinical algorithms yet. In this article, we review the diagnosis and treatment of E. granulosus and E. multilocularis infections in the light of recent evidence.

Keywords: Echinococcus granulosus, Echinococcus multilocularis, Liver, Ultrasonography, Albendazole

Core tip: Echinococcus granulosus and Echinococcus multilocularis infections are the most common parasitic diseases of the liver. They could be asymptomatic for many years. Most of the asymptomatic patients are diagnosed incidentally. Ultrasonography is important in diagnosis. There is no standardized and widely accepted treatment approach.

INTRODUCTION

Cystic echinococcus (CE) is a parasitic illness, caused by infection with Echinococcus granulosus (E. granulosus) in its larval stage[1]. Although the disease occurs worldwide, it is endemic in Africa, South America, and Eurasia[2-4]. The liver is the most commonly affected organ; however, the lungs, spleen, kidney, brain, and breasts may be involved[5]. Mortality from CE is usually due to the development of complications and is reported to be 2%-4%[6,7]. The disease course is typically slow and most CE patients remain asymptomatic for several years. In addition, due to non-specific symptoms, the diagnosis is often incidental[8]. Hepatic alveolar echinococcus (AE) referring to the intrahepatic growth of the larvae of Echinococcus multilocularis (E. multilocularis) is a rare yet serious disease. When the epidemiology of AE is analyzed, it is striking that the disease is encountered in the northern hemisphere only[9].

Complications of the echinococcal disease include allergic reactions to the dissemination of cyst contents due to spontaneous, traumatic or iatrogenic rupture, secondary infection, and cholangitis[3,10-12]. While most CE patients have a single cyst, 20%-40% tend to harbor multiple cysts[13].

Although a wide range of treatment methods have been identified (medical, percutaneous, monitoring, and surgical), a standardized treatment protocol has yet to be defined.

In this article, we present an update on the diagnosis and treatment of the CE and AE diseases in the liver in the light of emanating evidence.

E. GRANULOSUS INFECTION

Life cycle

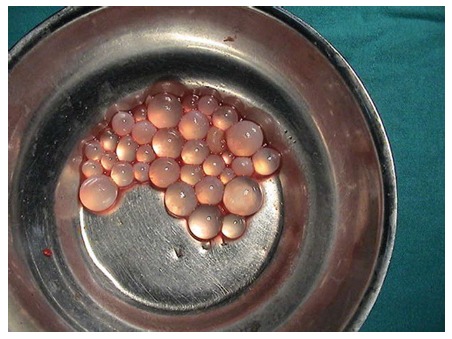

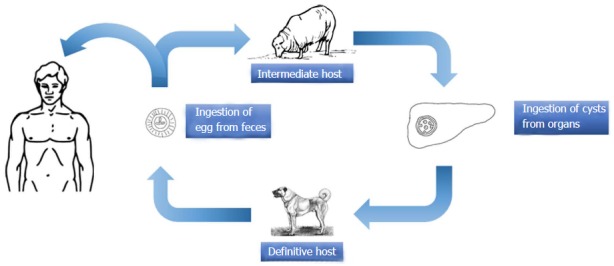

E. granulosus is a small sized tapeworm with 10 different genotypes. The definitive host of this parasite is the dog and other members of canids; the intermediate hosts include members of the ungulates such as sheep, goat, and pigs. The adult parasites localize in the liver of the definitive host; eggs are excreted via the stool of the host. Upon oral ingestion of the eggs by the intermediate host, the eggs hatch within the stomach and intestine. Oncosphere larvae emerge and cling onto the small intestine by its hooks. Subsequently, the oncosphere larvae migrate to organs such as the liver and lungs through the blood and lymph vessels. Humans are accidental hosts and not essential to the life-cycle of Echinococcus. Infection occurs after the oral ingestion of eggs. The eggs grow inside the host organs and form a cyst (hydatid cyst). Hydatid cysts are round in shape and are usually filled with a clear fluid. The inner part of the cyst features a germinating membrane while the outer part features a laminated layer. In time, the parasite matures and evokes a granulomatous inflammatory reaction which leads to walling off of the cyst by fibrous tissue. In time, budding (germination) occurs from the germinative membrane and blisters are formed (Figure 1). The protoscolexes, which occur inside the organ that the definitive host consumed, open up and Echinococcus matures into adult from clinging onto the intestine of the definitive host, thus completing the cycle[14-17] (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Daughter vesicules of Echinococcus granulosus.

Figure 2.

Life circle of Echinococcus granulosus.

Clinical presentation

Most patients have an asymptomatic disease course. The most important reason for this is the slow growth rate of the cysts (1-5 mm per year). Therefore, symptoms usually develop in adulthood[13,14,18]. The most common presenting symptoms are discomfort in the right upper quadrant of abdomen and loss of appetite. Other symptoms may include pain caused by an increase in the size of the cyst, anaphylactic reaction[11] induced by the rupture of the cyst, hepatitis, and cholangitis due to biliary obstruction caused by the daughter vesicles[19], secondary infection of the cyst, embolism[14], and subphrenic or intracystic abscess[13]. In 90% of the patients, the cysts open into the biliary tract, which causes the complications listed above[20]. In approximately 10% of cases, intraperitoneal rupture of the cyst induces anaphylaxis. In addition, secondary CE may develop due to the rupture of the cyst, and this may lead to a much larger mass developing over a relatively short period[13]. Patients are usually diagnosed incidentally during radiological examination conducted for complaints unrelated to CE. During physical examination, hepatomegaly, palpable mass in one right upper quadrant, and abdominal distension may be encountered as well.

For patients who develop hepatitis, colic pain, portal hypertension, acidity, pressure in inferior vena cava, and Budd-Chiari syndrome, liver hemangioma, liver cysts, adenoma, liver abscess, hepatocellular cancer, liver metastasis, and in addition, liver Echinococcus should be taken into account during the differential diagnosis of the masses that are found in the liver[21,22].

Diagnosis

Most of CE patients at the asymptomatic early stage are diagnosed incidentally. Diagnosis relies on imaging and immunological tests. Ultrasonography is a convenient tool for diagnosis that indicates the location, number, and size of the cysts with relative ease[2,3,13,18,23,24].

However, small-sized cysts may not be detected by ultrasonography. The criteria for classification of liver cysts on ultrasonography, which were first developed by Gharbi in 1981, were improved by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2001 (WHO-IWGE)[25,26] (Tables 1 and 2). The WHO classification includes cysts of unknown origin and includes modified subtypes of the Types 2 and 3 cysts[14]. There are three categories of cysts: Active, transitional, and inactive[27]. Types 1 and 2 cysts are considered “active” while Type 3 cysts are considered “transitional”. Types 4 and 5 cysts are categorized as “inactive”[27]. However, this classification has changed with the long term results of the medical and percutaneous treatment and the usage of the high-field magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Type 3 cysts, which are considered transitional, are further divided into two subgroups: CE3a (separated endocysts) and CE3b (solid type containing doughter vesicle)[7,28]. Some studies have suggested that CE3a cysts are inactive while CE3b cysts are active[14,29]. Ultrasonography may also be used for monitoring of the lesion. For patients who have received treatment, post-treatment follow-up examinations every 3-6 mo until stabilization of the cyst, and annual examinations thereafter, are recommended. In general, a period of 5 years without recurrence is considered sufficient[30]. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computer tomography (CT) may be required in some cases, where ultrasonography fails to provide a definitive diagnosis. These include obese patients, patients with subdiaphragmatic cyst or secondary infection of cysts, complicated cases such as biliary fistula, cases with extra-abdominal spread, and patiens who have a common disease. CT and MRI are particularly useful for pre-operative and follow-up examinations. Use of MRI for diagnosis and follow-up examination is known to be superior to CT[28,31,32].

Table 1.

The Gharbi classification of hydatid cysts

| Type | Characteristics |

| I | Unilocular cyst, wall and internal echogonicities |

| II | Cyst with detached membrane (water-lily sign) |

| III | Multivesicular, multiseptated cyst, daughter cyst (honeycomb pattern) |

| IV | Hererogeneous cyst, no daughter vesicules |

| V | Cyst with partially or completely calcified wall |

Table 2.

The World Health Organization classification of hydatid cysts

| WHO stage | Characteristics | Activity |

| CE1 | Uniloculer, anechoic cyst with double line sign | Active |

| CE2 | Multiseptated “rosette-like” “honeycomb patern” cyst | Active |

| CE3a | Cyst with detached membrane (water-lily sign) | Transitional |

| CE3b | Daughter cysts in solid matrix | Transitional |

| CE4 | Hererogeneous cyst, no daughter vesicules | Inactive |

| CE5 | Solid matrix with calcified wall | Inactive |

WHO: World Health Organization.

There are no workups amongst the routine blood workups that may be used specifically for CE. Hyperbilirubinemia and increased levels of alkaline phosphatase and gamma glutamyl transferase may indicate opening of the cyst into the biliary tract[15,30,33]. Although EC is a parasitic infection, eosinophilia may not be always present. Serologic diagnostic methods are used to support the radiological diagnosis and for follow-up assessment. The immunological response to the disease tends to vary from one individual to another. Rugged and intact cysts tend to show minimal immune response, while leaking or ruptured cysts tend to evoke a strong immune response[2,34,35].

The indirect hemagglutination (IHA) is usually non-specific and is of value in tandem with other investigations such as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and immunoblotting[36]. Concomitant use of IHA and ELISA is associated with diagnostic sensitivity rates up to 85%-96%[37-41]. Immunoblotting is generally used to confirm the diagnosis in cases where IHA and ELISA findings are not definitive[14]. E. granulosus antigen B and antigen 5 (Ag5) are the most specific antigens used for immunological diagnosis[2,35]. However, these immunological methods often show cross reactivity with other parasitic antigens or with non-parasitic diseases such as malignancy or liver cirrhosis[15,42-45]. Sensitivity of the serological tests tends to vary with the location, stage, and size of the cyst[11].

While seronegativity is observed in 20% of patients with CE, those with multiple cysts are usually seropositive. Rate of seronegativity is relatively higher in patients with CE1, CE4, and CE5 cyst types as compared to those with CE2 and CE3 types. Moreover, seropositive patients may continue to remain so for more than 10 years despite treatment[14,46-48]. This may lead to unnecessary treatment and an increase in costs.

Percutaneous fine needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy under ultrasound guidance is used in suspected cases with equivocal radiological and serological test results. Observing the protoscolexes and cyst membranes, or Echinococcal antigen or DNA in aspirated fluid confirms the diagnosis[49]. Percutaneous procedure requires meticulous care due to the associated risk of anaphylaxis; informed consent of the patient should be obtained prior to the procedure[50]. Anaphylaxis risk of FNA is 2.5%[51]. In order to prevent secondary CE, pretreatment with albendazole for 4 d prior to the biopsy and continuation of treatment for one month after the biopsy are recommended[20,52].

Treatment and management of E. granulosus infection

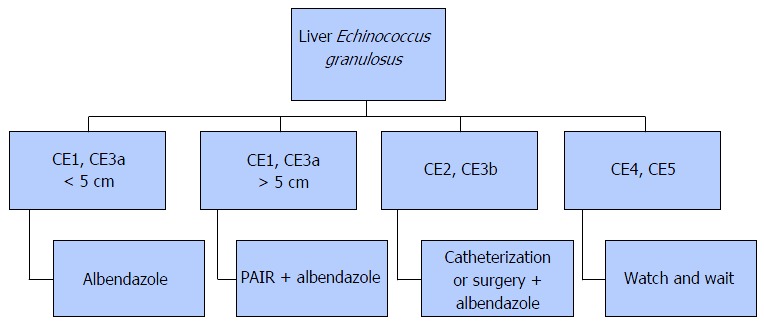

The treatment options for CE included surgery, percutaneous treatment, medical pharmacotherapy, and monitoring[10]. In the literature, there is no randomized clinical study that compares the treatment methods with each other. Therefore, there is no standardized and widely accepted treatment approach for CE either[14]. The treatment planning is done according to the WHO diagnostic classification. In case CE1 and CE3a cysts are < 5 cm in diameter, albendazole alone may suffice, while for cysts exceeding 5 cm in size, the puncture, aspiration, injection of a scolecidal agent, and reaspiration (PAIR) treatment in tandem with albendazole is preferred. Types CE2 and CE3b cysts are treated by catheterization or surgery. For types CE4 and CE5 inactive cysts, monitoring is often sufficient[10] (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Treatment algoritm for Echinococcus granulosus infection. PAIR: Puncture, aspiration, injection of a scolecidal agent, and reaspiration.

Medical treatment: Exclusive medical pharmacotherapy is used in special cases where surgical or percutaneous treatment (such as elderly patients, cases with high comorbidity, patients who opt out of surgical and percutaneous treatment, and inoperable cases) is not suitable, or as an adjunct to surgical and percutaneous treatment.

Ever since benzimidazoles became available for use in 1970s, therapeutic efficacy of albendazole and mebendazole for larval stage of E. granulosus has been proved[14]. At present, albendazole is the most commonly used drug in the treatment of E. granulosus infection[53]. The dose of albendazole is 10-15 mg/kg per day and the treatment usually lasts for 3-6 mo. Efficacy of mebendazole is comparable to that of albendazole, but requires higher doses for a longer period of time, due to its poor absorption[53-55]. The dose of mebendazole is 40-50 mg/kg per day for the patients who can not use albendasole.

With benzimidazoles, the duration of treatment is 3-6 mo without interruption for CE1, CE3a cysts that are < 5 cm[10,56]. Studies have demonstrated that 28.5%-58% of patients who undergo medical treatment are cured, and that cure rates do not increase with the increase in the duration of treatment[54,57-61].

According to the recommendations of WHO, the medical treatment should be initiated 4-30 d prior to the surgical operation and continued for at least 1 mo thereafter for albendazole, and at least 3 mo for mebendazole. Medical pharmacotherapy is also indicated in patients with spontaneous or traumatic ruptured of cysts. In these cases, too, albendazole should be used for at least 1 mo or mebendazole for 3 mo[62-64].

In a large study (929 cysts) of the effectiveness of medical therapy in late stages, albendazole therapy was associated with a significantly higher incidence of degenerative changes than that with mebendazole therapy (82.2% vs 56.1%; P < 0.001). However, the relapse rates were comparable between the two groups[65].

Headache, nausea, neutropenia, hair loss, and hepatotoxicity are the most commonly reported side effects of albendazole and mebendazole. Monthly monitoring of leukocyte counts and liver function tests is recommended in patients who experience significant side effects. Contraindications to medical treatment include liver failure, pregnancy, and bone marrow suppression[13].

Praziquantel has protoscolicidal activity and can be used for treatment of CE, either as a standalone therapy or in combination with albendazole. A study suggested higher efficacy of the combination of praziquantel plus albendazole[66]. More studies on the efficacy of praziquantel are required.

Percutaneous treatment: The percutaneous treatment methods defined in the 1980s for liver CE continue to be popular today[67-70]. These are classified under two main categories. The first and more popular one is the PAIR method[71]. This method is based on the destruction of the germinal membrane by use of a scolicidal agent. However, PAIR is not a suitable method for cysts that contain daughter vesicles and for multi-vesicular cysts that have a higher solid content[7,69,72].

Secondary percutaneous treatment modalities include catheterization of the cyst with a broad tube to remove the solid contents of the cyst as well as the daughter vesicles. Several catheterization methods such as percutaneous evacuation, a modified catheterization technique, and dilatable multi-function trocar have been described[73-75]. This treatment method can be used for treatment of Types CE2 and CE3a cysts and for post-PAIR relapsing cysts[76].

A review of percutaneous CE treatment (n = 5.943) revealed a 0.03% incidence of lethal anaphylaxis and 1.7% incidence of allergic reactions[49]. Using albendazole starting from 4 h prior to the percutaneous treatment until 30 d after the percutaneous treatment is convenient[10].

The PAIR treatment is a less invasive method than surgery. In selected patients (CE1 and CE3b) success rates of up to 97% have been reported; the reported mortality and morbidity rates have varied from 0%-1% to 8.5%-32%[77-80]. In a study of ethanol plus PAIR treatment (n = 231), only one case of relapse was reported[80]. Eleven percent to thirteen percent of patients undergoing PAIR tend to develop fever and rash; however, the risk of anaphylaxis is quite low[77,81].

PAIR treatment is not recommended for the cysts which are containing materials that can not be absorbed, cysts which carry the risk of spread into the abdominal cavity, cysts that have already opened into the peritoneal cavity or biliary tract, and inactive and calcified cysts[7].

The relation of the cyst with the biliary tract should be examined prior to administration of scolicidal agent. Although no cases of scolicidal agent-related cholangitis after PAIR procedure have been reported, several such cases have been reported after surgical procedure[82-84]. The commonly used scolicidal agents used during PAIR are hypertonic saline and ethanol[14]. Successful intra-cystic application of albendazole and mebendazole solutions as scolicidal agents during PAIR has been reported in sheep[85].

The reported success rate of percutaneous treatment plus albendazole in non-complicated cysts is similar to that of surgery but has the advantage of a shorter duration of hospital stay[86]. In a retrospective comparison of conservative surgery and PAIR, the incidence of biliary fistula and residual cavity relapse was considerably lower with the latter[87].

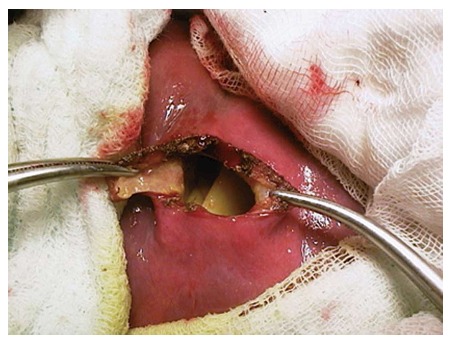

Surgical treatment: While surgical treatment was once the most commonly used treatment modality, it is currently, to a large extent, reserved for complicated cysts (such as cysts that develop biliary fistula or perforated cysts) or is applied to the cysts that contain doughter cysts (CE2, CE3b). In addition, it is a suitable treatment option for superficial cysts that are smaller than 10 cm or are at high risk of rupture and for cases not suitable for percutaneous treatment[7,10,53,88]. The surgical treatment options include open surgery and laparoscopic surgery[5,89,90]. Open surgical options include radical and conservative surgery. Radical surgery refers to the removal of the cyst along with the pericystic membrane (Figure 4) and may also include liver resection if indicated. Conservative surgery includes removal of the cyst contents only, while the pericystic membrane is retained (Figure 5). Omentoplasty, external drainage, or obliteration of the residual cavity by imbricating sutures from within (capitonnage) is used for drainage from the residual cavity. The complication rates of the surgical treatment options vary between 3%-25%, while the recurrence rates vary between 2% and 40%[89,91-93]. The complication and recurrence rates tend to differ based on the location and size of the cyst, as well as the experience of the surgeon and the selected treatment method.

Figure 4.

An example of pericyctectomy material.

Figure 5.

An example of concervative surgery.

It is not clear which one of the given treatment options is the safest and the most effective. However, recurrence and complication rates tend to be higher with conservative surgery as compared to those with radical surgery[94]. Many retrospective studies have revealed similar results[93,95].

The recurrences usually occur due to failure of complete removal of the endocysts and/or their dissemination during the surgery. For this reason, special attention should be paid to prevent spread during the operation[96,97]. Of note, spread during the surgery may also lead to other complications such as anaphylaxis.

The most common complication of liver EC is the infection and the contact with the biliary tract. The contact of the cyst with the biliary tracts is encountered in 3%-7% of all cases[98]. A relationship between cyst size and its contact with the biliary tract has been reported. In cases where the radius of the cyst is > 7.5 cm, the sensitivity of the contact of the cyst with the biliary tract is reported to be 73% while its specificity is indicated to be 79%[99]. Prior to intraoperative administration of drugs in the cyst, the relation of the cyst with the biliary tract should be ascertained as protoscolicidal agents are known to induce sclerosis, cholangitis, and pancreatitis.

In case of preoperative evidence of opening of the cyst into the biliary tract, sphincterotomy by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) prior to surgery decreases the risk of postoperative external fistula from 11.1% to 7.6%[100]. When the relation of the cyst with the biliary tract is noticed during the surgery, presence of a cystic component within the biliary branches or within the common biliary duct should be checked. For this, intraoperative cholangiography is often required. In addition, the width of the biliary tract would be in normal range if there is no cystic component within the biliary branches or within the common biliary duct. The biliary tracts, which can be clearly seen through the cyst, should be sutured. In case there is a cystic component inside the biliary tract, the biliary tract would be widened. In such cases, removal of the cystic components within the biliary branches and applying T-tube or choledochoduodenostomy is recommended[101,102]. In addition, postoperative bilioma or high flow biliary fistula requires ERCP and sphincterotomy along with nasobiliary drainage or biliary stenting[103,104].

The most commonly used protoscolicidal agent during the surgery is 20% hypertonic saline. The hypertonic saline should be in contact with the germinal membrane for at least 15 min. Albendazole, ivermectin, and praziquantel can also be used as protoscolicidal agents[105,106]. In a recently conducted ex vivo research, use of selenium nano-particles (250-500 μg/mL) as a protoscolicidal agent for 10-20 min showed good results[107].

Intraoperative dissemination of the mass in the peritoneum should be rinsed with hypertonic saline. Postoperative albendazole for 3-6 mo plus praziquantel for 7 d is recommended[108].

In a retrospective review of conservative surgery methods (n = 304), use of external drainage was associated with a statistically significant increase in complication rates as compared to patients who received omentoplasty or capitonnage[109]. In another randomized clinical trial and one retrospective study, patients who received omentoplasty in addition to the conservative surgery showed fewer complications as compared to patients with external drainage[5,110].

The first laparoscopic surgery for CE was reported in 1992[111]. While the laparoscopic surgery offers some advantages such as shorter duration of hospital stay, lesser postoperative pain, and lower infection rates, it is applicable only to selected cases. Further laparoscopic procedures are associated with an increased risk of intraoperative dissemination of the cyst contents due to the increased pressure inside the mass[5,88]. No studies comparing open surgery with laparoscopic surgery were retrieved on the literature search. Appropriate patient selection is critical to the success of laparoscopic surgery. Deep-seated cysts in the hepatic parenchyma, posterior cysts close to the vena cava, multiple cysts (> 3), and cysts with calcified walls are unsuitable for laparoscopic surgery[88,112-114].

Monitoring: Some studies suggest that inactive cysts, such as CE4 and CE5, require no treatment[7,49,76]. However, more studies in this regard are required.

E. MULTILOCULARIS INFECTION

Life cycle

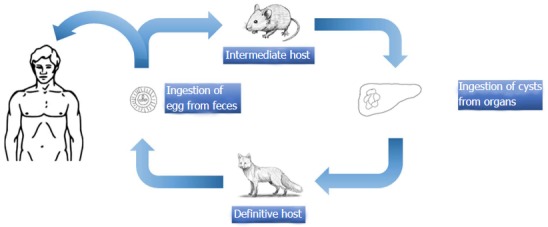

E. multilocularis is a small cestode. The definitive hosts of the sylvatic cycle are feral carnivores, and the definitive hosts of the synanthrophic cycle are domestic cats and dogs. The fully grown parasites within the small intestine of the definitive host excrete their eggs with the feces of the definitive host. Upon ingestion of the eggs by intermediate hosts such as small rodents, echinococcal metacestodes form alveolar structures with multiple vesicles of different sizes within the liver. Humans get infected after oral ingestion of eggs[3,17]. Each vesicle has a structure, similar to the cysts of E. granulosus[115]. Potential complications include the formation of pseudocysts due to fluid accumulation or central necrosis. Small cysts usually do not contain liquid within them and are semisolid in structure[16] (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Life circle of Echinococcus multilocularis.

Clinical symptoms of E. multilocularis infections

The latent period for infection in which the patients are asymptomatic lasts around 5-15 years and is rather longer compared to the CE. In general, the AE is set into the right lobe of the liver and its size may vary from a few millimeters to 20 cm[11,13]. The AE may spread locally or metastasize to the brain, bones, and lungs via blood[115]. Extrahepatic manifestations are rare in primary disease[11]. The typical presenting symptoms include fatigue, weight loss, abdominal pain, and signs of hepatitis or hepatomegaly. Up to one-third of patients suffer from hepatitis and abdominal pain[115-117]. The prognosis for untreated cases or cases with incomplete treatment is grim; liver failure, splenomegaly, portal hypertension, and acidity may occur in advanced stages. The life expectancy may extend up to 20 years with treatment[118].

Diagnosis of E. multilocularis infection

The radiological imaging methods are the main methods of diagnosis of AE and the serologic examinations are used to support the diagnosis[3,4,10,119]. Ultrasonography is the diagnostic method of choice. On ultrasonography, a pseudotumoral mass with hypo and hyperechoic areas together that contain irregular, limited, and dispersed calcifications is diagnostic[120,121]. Doppler ultrasonography may be useful for imaging of biliary tracts and vascular infiltrations. Although CT renders the anatomical details in a better manner, MRI is considered the best method to determine invasion of the contiguous structures[120-122]. Percutaneous cholangiography is an important method for diagnosis in order to view the relation between the alveolar lesions and the biliary tracts. In addition cranial and thoracic imaging should be required to rule out extra-hepatic involvement in AE patients[120]. Despite the fact that the fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography can be used for diagnosis, negative results do not necessarily mean that the parasite is active[123]. The WHO classification developed for Echinococcus is based on the imaging methods and aims to establish standardization in the diagnosis and treatment of the disease[3,10,124]. WHO-IWGE PNM classification system resembles the TNM classification used for the tumors[3,124]. P indicates the size and location of the parasite within the liver, N indicates the adjunct organ involvement while M indicates distant metastasis (Table 3).

Table 3.

PNM classification of Echinococcus multilocularis[146]

| P | Hepatic localization of the metacestode |

| Px | Primary lesion unable to be assessed |

| P0 | No detectable hepatic lesion |

| P1 | Peripheral lesion without biliary or proximal vascular involvement |

| P2 | Central lesions with biliary or proximal vascular involvement of one lobe |

| P3 | Central lesions with biliary or proximal vascular involvement of both lobes or two hepatic veins or both |

| P4 | Any lesion with extension along the portal vein, inferior vena cava or hepatic arteries |

| N | Extra-hepatic involvement of neighbouring organs |

| Nx | Not evaluable |

| N0 | No regional involvement |

| N1 | Involvement of neighboring organs or tissues |

| M | Absence or presence of distant metastasis |

| Mx | Not completely assessed |

| M0 | No metastasis on chest radiograph and computer tomography brain scan |

| M1 | Metastasis present |

The immunological diagnostic methods are helpful for diagnosis as well as for monitoring the effectiveness of the treatment[125,126]. The serological investigations for AE (ELISA or IHA test) are more specific than the ones used for the diagnosis of CE (antigens Em2 and Em II/3-10 are highly specific to AE)[127]. However, EM2-ELISA may remain positive for many years even in the treated cases as the EM2 antigen is present in inactive lesions. The most active component of AE is the protoscolex that has EM16 and EM18 antigens. The activity of the lesion can be obtained by using those antigens in immunoblot tests[128]. In addition, EM18 is helpful for distinction between AE and CE[2]. In some studies, AE patients had high levels of IgG1 and IgG4 antibodies and their IgG4 antibody levels decreased after treatment. Therefore, an increase in IgG4 levels may be a surrogate marker of reactivation of the parasite[129-132]. Demonstration of alveolar vesicles in the samples extracted by percutaneous needle biopsy in suspected cases helps confirm the diagnosis. Although PCR imaging of the E. multilocularis DNA in the liver biopsy samples has high positive predictive value, negative results do not necessarily rule out the presence of an active parasite[10]. There are several studies evaluating the serologic agents best suited for post-treatment follow-up[133,134].

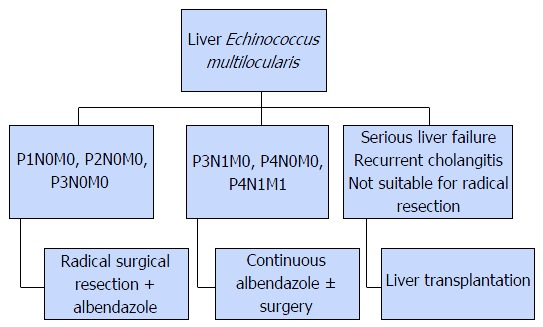

Treatment and management of E. multilocularis infection

AE is comparatively difficult to treat than CE. The main treatment modalities are medical pharmacotherapy and surgery (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Treatment algoritm for Echinococcus multilocularis infection.

Surgical treatment is the primary method for AE; radical resection is often required for hepatic lesions. Conservative and palliative surgery is not recommended since they offer no advantage over medical pharmacotherapy[135,136]. Treatment is based on pre-operative assessment and the disease stage as per the WHO-IWGE PNM classification[124]. Liver transplantation is an option for patients with advanced stage liver failure, patients that have recurrent cholangitis, and patients unsuitable for radical surgery. Extrahepatic spread of AE during surgery is particularly hazardous in liver transplant recipients, due to drug-induced immunosuppression[10]. These patients are at risk of relapse[137].

Although there is no information regarding the effectiveness of pre-operative pharmacotherapy, it is generally used for liver transplant recipients. Postoperative albendazole is recommended in all patients for at least 2 years[30,137]. Although there are alternative drugs such as mebendazole, praziquantel, and amphotericin, none is as effective as albendazole[138,139]. In a recently conducted study, it was revealed that nitazoxanide has no effect on the treatment of AE[140].

Optimal duration of albendazole treatment in patients not treated by surgery is not clear. However, cases have been documented where albendazole was continuously used for up to 20 years without any complications[10]. The use of albendazole in patients who do not undergo surgical treatment increases the 15-year survival from 0% to 53%-80%[141-145]. Interventions such as endoscopic sclerosis of the varicose veins of the esophagus and stent implantation may be required during treatment[53].

CONCLUSION

E. granulosus and E. multilocularis infections are the most common parasitic diseases that involve the liver. Due to the typical slow growth, these often present in adulthood. Their symptoms include right upper quadrant abdominal pain, chlorosis, cholangitis, and anaphylaxis due to cyst rupture. AE is one of the most fatal helminthic infections. Ultrasonography plays a special role in diagnosis. WHO classification is used for staging and treatment selection. Immunological diagnostic methods are used to support the diagnosis. Cysts smaller than 5 cm (WHO stages CE1 and CE3a) are treated with albendazole only, while PAIR plus albendazole therapy is recommended for cysts > 5 cm. PAIR treatment for patients with CE2 and CE3b cysts is associated with frequent relapses. Therefore, broad tube percutaneous treatment should be considered in these cases. During open surgery and percutaneous treatment, all necessary efforts should be made to prevent dissemination of cyst contents; albendazole should be used at least for 4 d prior to such procedures and for 1 mo after the procedures. For AE, despite the fact that albendazole is not used preoperatively, postoperative treatment for 2 years is recommended. For CE, radical surgery is reported to be more effective than conservative surgery. For AE, the radical treatment option is also recommended as palliative surgery offers no advantages over medical treatment. Despite the fact that the general templates regarding the treatment seem clear, the lack of randomized clinical studies that compare the treatment options leads to failure in the selection of treatment.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Turkey

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare no conflict of interests for this article.

Peer-review started: April 28, 2016

First decision: June 16, 2016

Article in press: July 13, 2016

P- Reviewer: Grattagliano I, Reshetnyak VI, Tanaka N S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Li D

References

- 1.Li H, Song T, Shao Y, Aili T, Ahan A, Wen H. Comparative Evaluation of Liposomal Albendazole and Tablet-Albendazole Against Hepatic Cystic Echinococcosis: A Non-Randomized Clinical Trial. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e2237. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000002237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang W, McManus DP. Recent advances in the immunology and diagnosis of echinococcosis. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2006;47:24–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2006.00060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pawlowski ZS, Eckert DA, Vuitton DA, Ammann RW, Kern P, Craig PS, Dar K. Eckert J, Gemmell MA, Meslin F-X, Pawlowski ZS. WHO/OIE manual on echinococcosis in humans and animals: a public health problem of global concern. Paris, World Organisation for Animal Health; 2001. F, De Rosa F, Filice C, Gottstein B, Grimm F, Macpherson C.N.L, Sato N, Todorov T, Uchino J, von Sinner W, Wen H. Echinococcosis in humans: clinical aspects, diagnosis and treatment; pp. 20–72. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eckert J, Deplazes P. Biological, epidemiological, and clinical aspects of echinococcosis, a zoonosis of increasing concern. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17:107–135. doi: 10.1128/CMR.17.1.107-135.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dziri C, Haouet K, Fingerhut A. Treatment of hydatid cyst of the liver: where is the evidence? World J Surg. 2004;28:731–736. doi: 10.1007/s00268-004-7516-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Belhassen-García M, Romero-Alegria A, Velasco-Tirado V, Alonso-Sardón M, Lopez-Bernus A, Alvela-Suarez L, del Villar LP, Carpio-Perez A, Galindo-Perez I, Cordero-Sanchez M, et al. Study of hydatidosis-attributed mortality in endemic area. PLoS One. 2014;9:e91342. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Junghanss T, da Silva AM, Horton J, Chiodini PL, Brunetti E. Clinical management of cystic echinococcosis: state of the art, problems, and perspectives. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;79:301–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manzano-Román R, Sánchez-Ovejero C, Hernández-González A, Casulli A, Siles-Lucas M. Serological Diagnosis and Follow-Up of Human Cystic Echinococcosis: A New Hope for the Future? Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:428205. doi: 10.1155/2015/428205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu W, Delabrousse É, Blagosklonov O, Wang J, Zeng H, Jiang Y, Wang J, Qin Y, Vuitton DA, Wen H. Innovation in hepatic alveolar echinococcosis imaging: best use of old tools, and necessary evaluation of new ones. Parasite. 2014;21:74. doi: 10.1051/parasite/2014072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brunetti E, Kern P, Vuitton DA. Expert consensus for the diagnosis and treatment of cystic and alveolar echinococcosis in humans. Acta Trop. 2010;114:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McManus DP, Gray DJ, Zhang W, Yang Y. Diagnosis, treatment, and management of echinococcosis. BMJ. 2012;344:e3866. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e3866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Torgerson PR, Keller K, Magnotta M, Ragland N. The global burden of alveolar echinococcosis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4:e722. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nunnari G, Pinzone MR, Gruttadauria S, Celesia BM, Madeddu G, Malaguarnera G, Pavone P, Cappellani A, Cacopardo B. Hepatic echinococcosis: clinical and therapeutic aspects. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:1448–1458. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i13.1448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rinaldi F, Brunetti E, Neumayr A, Maestri M, Goblirsch S, Tamarozzi F. Cystic echinococcosis of the liver: A primer for hepatologists. World J Hepatol. 2014;6:293–305. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v6.i5.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eckert JGM, Meslin FX, Pawlowski ZS, editors . WHOI/OIE manual on echinococcosis in humans and animals: a public health problem of global concern. Paris: World Health Organization for Animal Health; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thompson RC, McManus DP. Aetiology: parasites and lifecycles. In: Eckert J, Gemmell M, Meslin FX, Pawlowski Z, editors. WHOI/OIE manual on echinococcosis in humans and animals: a public health problem of global concern. Paris: World Organisation for Animal Health; 2001. pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thompson RC. Biology and systematics of Echinococcus. The biology of Echinococcus and hydatid disease. In: Thompson RCA, Lymbery AJ, editors. Wallingford: CAB International; 1995. pp. 1–50. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moro P, Schantz PM. Echinococcosis: a review. Int J Infect Dis. 2009;13:125–133. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2008.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Atli M, Kama NA, Yuksek YN, Doganay M, Gozalan U, Kologlu M, Daglar G. Intrabiliary rupture of a hepatic hydatid cyst: associated clinical factors and proper management. Arch Surg. 2001;136:1249–1255. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.136.11.1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pedrosa I, Saíz A, Arrazola J, Ferreirós J, Pedrosa CS. Hydatid disease: radiologic and pathologic features and complications. Radiographics. 2000;20:795–817. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.20.3.g00ma06795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cattaneo F, Graffeo M, Brunetti E. Extrahepatic textiloma long misdiagnosed as calcified echinococcal cyst. Case Rep Gastrointest Med. 2013;2013:261685. doi: 10.1155/2013/261685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Polat P, Kantarci M, Alper F, Suma S, Koruyucu MB, Okur A. Hydatid disease from head to toe. Radiographics. 2003;23:475–494; quiz 536-537. doi: 10.1148/rg.232025704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen H, Paolillo E, Bonifacino R, Botta B, Parada L, Cabrera P, Snowden K, Gasser R, Tessier R, Dibarboure L, et al. Human cystic echinococcosis in a Uruguayan community: a sonographic, serologic, and epidemiologic study. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1998;59:620–627. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1998.59.620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shambesh MA, Craig PS, Macpherson CN, Rogan MT, Gusbi AM, Echtuish EF. An extensive ultrasound and serologic study to investigate the prevalence of human cystic echinococcosis in northern Libya. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;60:462–468. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.60.462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gharbi HA, Hassine W, Brauner MW, Dupuch K. Ultrasound examination of the hydatic liver. Radiology. 1981;139:459–463. doi: 10.1148/radiology.139.2.7220891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.WHO Informal Working Group. International classification of ultrasound images in cystic echinococcosis for application in clinical and field epidemiological settings. Acta Trop. 2003;85:253–261. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(02)00223-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grisolia A, Troìa G, Mariani G, Brunetti E, Filice C. A simple sonographic scoring system combined with routine serology is useful in differentiating parasitic from non-parasitic cysts of the liver. J Ultrasound. 2009;12:75–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jus.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hosch W, Junghanss T, Stojkovic M, Brunetti E, Heye T, Kauffmann GW, Hull WE. Metabolic viability assessment of cystic echinococcosis using high-field 1H MRS of cyst contents. NMR Biomed. 2008;21:734–754. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kabaalioğlu A, Ceken K, Alimoglu E, Apaydin A. Percutaneous imaging-guided treatment of hydatid liver cysts: do long-term results make it a first choice? Eur J Radiol. 2006;59:65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2006.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brunetti E, White AC. Cestode infestations: hydatid disease and cysticercosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2012;26:421–435. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stojkovic M, Rosenberger K, Kauczor HU, Junghanss T, Hosch W. Diagnosing and staging of cystic echinococcosis: how do CT and MRI perform in comparison to ultrasound? PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6:e1880. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hosch W, Stojkovic M, Jänisch T, Heye T, Werner J, Friess H, Kauffmann GW, Junghanss T. MR imaging for diagnosing cysto-biliary fistulas in cystic echinococcosis. Eur J Radiol. 2008;66:262–267. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Filippou D, Tselepis D, Filippou G, Papadopoulos V. Advances in liver echinococcosis: diagnosis and treatment. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:152–159. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gottstein B. Molecular and immunological diagnosis of echinococcosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1992;5:248–261. doi: 10.1128/cmr.5.3.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ito A. Serologic and molecular diagnosis of zoonotic larval cestode infections. Parasitol Int. 2002;51:221–235. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5769(02)00036-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Craig PS, Rogan MT, Campos-Ponce M. Echinococcosis: disease, detection and transmission. Parasitology. 2003;127 Suppl:S5–S20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ortona E, Siracusano A, Castro A, Rigano R, Mühlschlegel F, Ioppolo S, Notargiacomo S, Frosch M. Use of a monoclonal antibody against the antigen B of Echinococcus granulosus for purification and detection of antigen B. Appl Parasitol. 1995;36:220–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lorenzo C, Ferreira HB, Monteiro KM, Rosenzvit M, Kamenetzky L, García HH, Vasquez Y, Naquira C, Sánchez E, Lorca M, et al. Comparative analysis of the diagnostic performance of six major Echinococcus granulosus antigens assessed in a double-blind, randomized multicenter study. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:2764–2770. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.6.2764-2770.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ortona E, Riganò R, Buttari B, Delunardo F, Ioppolo S, Margutti P, Profumo E, Teggi A, Vaccari S, Siracusano A. An update on immunodiagnosis of cystic echinococcosis. Acta Trop. 2003;85:165–171. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(02)00225-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ito A, Craig PS. Immunodiagnostic and molecular approaches for the detection of taeniid cestode infections. Trends Parasitol. 2003;19:377–381. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4922(03)00200-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang W, Li J, McManus DP. Concepts in immunology and diagnosis of hydatid disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2003;16:18–36. doi: 10.1128/CMR.16.1.18-36.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ortona E, Riganò R, Margutti P, Notargiacomo S, Ioppolo S, Vaccari S, Barca S, Buttari B, Profumo E, Teggi A, et al. Native and recombinant antigens in the immunodiagnosis of human cystic echinococcosis. Parasite Immunol. 2000;22:553–559. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3024.2000.00336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu D, Rickard MD, Lightowlers MW. Assessment of monoclonal antibodies to Echinococcus granulosus antigen 5 and antigen B for detection of human hydatid circulating antigens. Parasitology. 1993;106(Pt 1):75–81. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000074849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carmena D, Benito A, Eraso E. Antigens for the immunodiagnosis of Echinococcus granulosus infection: An update. Acta Trop. 2006;98:74–86. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Poretti D, Felleisen E, Grimm F, Pfister M, Teuscher F, Zuercher C, Reichen J, Gottstein B. Differential immunodiagnosis between cystic hydatid disease and other cross-reactive pathologies. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;60:193–198. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1999.60.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moro PL, Gilman RH, Verastegui M, Bern C, Silva B, Bonilla JJ. Human hydatidosis in the central Andes of Peru: evolution of the disease over 3 years. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:807–812. doi: 10.1086/520440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cirenei A, Bertoldi I. Evolution of surgery for liver hydatidosis from 1950 to today: analysis of a personal experience. World J Surg. 2001;25:87–92. doi: 10.1007/s002680020368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Perdomo R, Alvarez C, Monti J, Ferreira C, Chiesa A, Carbó A, Alvez R, Grauert R, Stern D, Carmona C, et al. Principles of the surgical approach in human liver cystic echinococcosis. Acta Trop. 1997;64:109–122. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(96)00641-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brunetti E, Junghanss T. Update on cystic hydatid disease. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2009;22:497–502. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e328330331c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Neumayr A, Troia G, de Bernardis C, Tamarozzi F, Goblirsch S, Piccoli L, Hatz C, Filice C, Brunetti E. Justified concern or exaggerated fear: the risk of anaphylaxis in percutaneous treatment of cystic echinococcosis-a systematic literature review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5:e1154. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.von Sinner WN, Nyman R, Linjawi T, Ali AM. Fine needle aspiration biopsy of hydatid cysts. Acta Radiol. 1995;36:168–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hira PR, Shweiki H, Lindberg LG, Shaheen Y, Francis I, Leven H, Behbehani K. Diagnosis of cystic hydatid disease: role of aspiration cytology. Lancet. 1988;2:655–657. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)90470-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Guidelines for treatment of cystic and alveolar echinococcosis in humans. WHO Informal Working Group on Echinococcosis. Bull World Health Organ. 1996;74:231–242. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Senyüz OF, Yeşildag E, Celayir S. Albendazole therapy in the treatment of hydatid liver disease. Surg Today. 2001;31:487–491. doi: 10.1007/s005950170106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nahmias J, Goldsmith R, Soibelman M, el-On J. Three- to 7-year follow-up after albendazole treatment of 68 patients with cystic echinococcosis (hydatid disease) Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1994;88:295–304. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1994.11812870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vutova K, Mechkov G, Vachkov P, Petkov R, Georgiev P, Handjiev S, Ivanov A, Todorov T. Effect of mebendazole on human cystic echinococcosis: the role of dosage and treatment duration. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1999;93:357–365. doi: 10.1080/00034989958357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stojkovic M, Zwahlen M, Teggi A, Vutova K, Cretu CM, Virdone R, Nicolaidou P, Cobanoglu N, Junghanss T. Treatment response of cystic echinococcosis to benzimidazoles: a systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2009;3:e524. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Teggi A, Lastilla MG, De Rosa F. Therapy of human hydatid disease with mebendazole and albendazole. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:1679–1684. doi: 10.1128/aac.37.8.1679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Erzurumlu K, Hökelek M, Gönlüsen L, Tas K, Amanvermez R. The effect of albendazole on the prevention of secondary hydatidosis. Hepatogastroenterology. 2000;47:247–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Aktan AO, Yalin R. Preoperative albendazole treatment for liver hydatid disease decreases the viability of the cyst. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1996;8:877–879. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Arif SH, Shams-Ul-Bari NA, Zargar SA, Wani MA, Tabassum R, Hussain Z, Baba AA, Lone RA. Albendazole as an adjuvant to the standard surgical management of hydatid cyst liver. Int J Surg. 2008;6:448–451. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Manterola C, Mansilla JA, Fonseca F. Preoperative albendazole and scolices viability in patients with hepatic echinococcosis. World J Surg. 2005;29:750–753. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-7691-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gil-Grande LA, Rodriguez-Caabeiro F, Prieto JG, Sánchez-Ruano JJ, Brasa C, Aguilar L, García-Hoz F, Casado N, Bárcena R, Alvarez AI. Randomised controlled trial of efficacy of albendazole in intra-abdominal hydatid disease. Lancet. 1993;342:1269–1272. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92361-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bildik N, Cevik A, Altintaş M, Ekinci H, Canberk M, Gülmen M. Efficacy of preoperative albendazole use according to months in hydatid cyst of the liver. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41:312–316. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000225572.50514.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Franchi C, Di Vico B, Teggi A. Long-term evaluation of patients with hydatidosis treated with benzimidazole carbamates. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:304–309. doi: 10.1086/520205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cobo F, Yarnoz C, Sesma B, Fraile P, Aizcorbe M, Trujillo R, Diaz-de-Liaño A, Ciga MA. Albendazole plus praziquantel versus albendazole alone as a pre-operative treatment in intra-abdominal hydatisosis caused by Echinococcus granulosus. Trop Med Int Health. 1998;3:462–466. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1998.00257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Filice C, Pirola F, Brunetti E, Dughetti S, Strosselli M, Foglieni CS. A new therapeutic approach for hydatid liver cysts. Aspiration and alcohol injection under sonographic guidance. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:1366–1368. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)90358-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ben Amor N, Gargouri M, Gharbi HA, Golvan YJ, Ayachi K, Kchouck H. [Trial therapy of inoperable abdominal hydatid cysts by puncture] Ann Parasitol Hum Comp. 1986;61:689–692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mueller PR, Dawson SL, Ferrucci JT, Nardi GL. Hepatic echinococcal cyst: successful percutaneous drainage. Radiology. 1985;155:627–628. doi: 10.1148/radiology.155.3.3890001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gargouri M, Ben Amor N, Ben Chehida F, Hammou A, Gharbi HA, Ben Cheikh M, Kchouk H, Ayachi K, Golvan JY. Percutaneous treatment of hydatid cysts (Echinococcus granulosus) Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1990;13:169–173. doi: 10.1007/BF02575469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.World Health Organization. PAIR: Puncture, Aspiration, Injection, Re- Aspiration. An option for the treatment of Cystic echinococcosis. WHO/CDS/CSR/APH/2001.6 Geneva, 2003: 1-4. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nasseri Moghaddam S, Abrishami A, Malekzadeh R. Percutaneous needle aspiration, injection, and reaspiration with or without benzimidazole coverage for uncomplicated hepatic hydatid cysts. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;2:CD003623. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003623.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Akhan O, Gumus B, Akinci D, Karcaaltincaba M, Ozmen M. Diagnosis and percutaneous treatment of soft-tissue hydatid cysts. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2007;30:419–425. doi: 10.1007/s00270-006-0153-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Schipper HG, Laméris JS, van Delden OM, Rauws EA, Kager PA. Percutaneous evacuation (PEVAC) of multivesicular echinococcal cysts with or without cystobiliary fistulas which contain non-drainable material: first results of a modified PAIR method. Gut. 2002;50:718–723. doi: 10.1136/gut.50.5.718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Vuitton DA, Wang XZ, Feng SL, Chen JS, Shou LY, Li SF, Ke TQ. PAIR-derived US-guided techniques for the treatment of cystic echinococcosis: a Chinese experience (e-letter) Gut. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 76.Brunetti E, Garcia HH, Junghanss T. Cystic echinococcosis: chronic, complex, and still neglected. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5:e1146. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ustünsöz B, Akhan O, Kamiloğlu MA, Somuncu I, Uğurel MS, Cetiner S. Percutaneous treatment of hydatid cysts of the liver: long-term results. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;172:91–96. doi: 10.2214/ajr.172.1.9888746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Giorgio A, de Stefano G, Esposito V, Liorre G, Di Sarno A, Giorgio V, Sangiovanni V, Iannece MD, Mariniello N. Long-term results of percutaneous treatment of hydatid liver cysts: a single center 17 years experience. Infection. 2008;36:256–261. doi: 10.1007/s15010-007-7103-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Salama H, Farid Abdel-Wahab M, Strickland GT. Diagnosis and treatment of hepatic hydatid cysts with the aid of echo-guided percutaneous cyst puncture. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:1372–1376. doi: 10.1093/clinids/21.6.1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Filice C, Brunetti E. Use of PAIR in human cystic echinococcosis. Acta Trop. 1997;64:95–107. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(96)00642-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Men S, Hekimoğlu B, Yücesoy C, Arda IS, Baran I. Percutaneous treatment of hepatic hydatid cysts: an alternative to surgery. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;172:83–89. doi: 10.2214/ajr.172.1.9888745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Castellano G, Moreno-Sanchez D, Gutierrez J, Moreno-Gonzalez E, Colina F, Solis-Herruzo JA. Caustic sclerosing cholangitis. Report of four cases and a cumulative review of the literature. Hepatogastroenterology. 1994;41:458–470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Belghiti J, Benhamou JP, Houry S, Grenier P, Huguier M, Fékété F. Caustic sclerosing cholangitis. A complication of the surgical treatment of hydatid disease of the liver. Arch Surg. 1986;121:1162–1165. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1986.01400100070014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Taranto D, Beneduce F, Vitale LM, Loguercio C, Del Vecchio Blanco C. Chemical sclerosing cholangitis after injection of scolicidal solution. Ital J Gastroenterol. 1995;27:78–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Paksoy Y, Odev K, Sahin M, Dik B, Ergül R, Arslan A. Percutaneous sonographically guided treatment of hydatid cysts in sheep: direct injection of mebendazole and albendazole. J Ultrasound Med. 2003;22:797–803. doi: 10.7863/jum.2003.22.8.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Khuroo MS, Wani NA, Javid G, Khan BA, Yattoo GN, Shah AH, Jeelani SG. Percutaneous drainage compared with surgery for hepatic hydatid cysts. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:881–887. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709253371303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Gupta N, Javed A, Puri S, Jain S, Singh S, Agarwal AK. Hepatic hydatid: PAIR, drain or resect? J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:1829–1836. doi: 10.1007/s11605-011-1649-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Dervenis C, Delis S, Avgerinos C, Madariaga J, Milicevic M. Changing concepts in the management of liver hydatid disease. J Gastrointest Surg. 2005;9:869–877. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2004.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gollackner B, Längle F, Auer H, Maier A, Mittlböck M, Agstner I, Karner J, Langer F, Aspöck H, Loidolt H, et al. Radical surgical therapy of abdominal cystic hydatid disease: factors of recurrence. World J Surg. 2000;24:717–721. doi: 10.1007/s002689910115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.El Malki HO, El Mejdoubi Y, Souadka A, Mohsine R, Ifrine L, Abouqal R, Belkouchi A. Predictive factors of deep abdominal complications after operation for hydatid cyst of the liver: 15 years of experience with 672 patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206:629–637. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Buttenschoen K, Carli Buttenschoen D. Echinococcus granulosus infection: the challenge of surgical treatment. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2003;388:218–230. doi: 10.1007/s00423-003-0397-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Daradkeh S, El-Muhtaseb H, Farah G, Sroujieh AS, Abu-Khalaf M. Predictors of morbidity and mortality in the surgical management of hydatid cyst of the liver. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2007;392:35–39. doi: 10.1007/s00423-006-0064-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Aydin U, Yazici P, Onen Z, Ozsoy M, Zeytunlu M, Kiliç M, Coker A. The optimal treatment of hydatid cyst of the liver: radical surgery with a significant reduced risk of recurrence. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2008;19:33–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Yüksel O, Akyürek N, Sahin T, Salman B, Azili C, Bostanci H. Efficacy of radical surgery in preventing early local recurrence and cavity-related complications in hydatic liver disease. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:483–489. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0301-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Tagliacozzo S, Miccini M, Amore Bonapasta S, Gregori M, Tocchi A. Surgical treatment of hydatid disease of the liver: 25 years of experience. Am J Surg. 2011;201:797–804. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2010.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kapan M, Kapan S, Goksoy E, Perek S, Kol E. Postoperative recurrence in hepatic hydatid disease. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:734–739. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2005.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lissandrin R, Agliata S, Brunetti E. Secondary peritoneal echinococcosis causing massive bilateral hydronephrosis and renal failure. Int J Infect Dis. 2013;17:e141–e142. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2012.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kumar R, Reddy SN, Thulkar S. Intrabiliary rupture of hydatid cyst: diagnosis with MRI and hepatobiliary isotope study. Br J Radiol. 2002;75:271–274. doi: 10.1259/bjr.75.891.750271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kilic M, Yoldas O, Koc M, Keskek M, Karakose N, Ertan T, Gocmen E, Tez M. Can biliary-cyst communication be predicted before surgery for hepatic hydatid disease: does size matter? Am J Surg. 2008;196:732–735. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Galati G, Sterpetti AV, Caputo M, Adduci M, Lucandri G, Brozzetti S, Bolognese A, Cavallaro A. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiography for intrabiliary rupture of hydatid cyst. Am J Surg. 2006;191:206–210. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Bedirli A, Sakrak O, Sozuer EM, Kerek M, Ince O. Surgical management of spontaneous intrabiliary rupture of hydatid liver cysts. Surg Today. 2002;32:594–597. doi: 10.1007/s005950200107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Erzurumlu K, Dervisoglu A, Polat C, Senyurek G, Yetim I, Hokelek M. Intrabiliary rupture: an algorithm in the treatment of controversial complication of hepatic hydatidosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:2472–2476. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i16.2472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Agarwal S, Sikora SS, Kumar A, Saxena R, Kapoor VK. Bile leaks following surgery for hepatic hydatid disease. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2005;24:55–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Chowbey PK, Shah S, Khullar R, Sharma A, Soni V, Baijal M, Vashistha A, Dhir A. Minimal access surgery for hydatid cyst disease: laparoscopic, thoracoscopic, and retroperitoneoscopic approach. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2003;13:159–165. doi: 10.1089/109264203766207672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Paksoy Y, Odev K, Sahin M, Arslan A, Koç O. Percutaneous treatment of liver hydatid cysts: comparison of direct injection of albendazole and hypertonic saline solution. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;185:727–734. doi: 10.2214/ajr.185.3.01850727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Dziri C, Haouet K, Fingerhut A, Zaouche A. Management of cystic echinococcosis complications and dissemination: where is the evidence? World J Surg. 2009;33:1266–1273. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-9982-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Mahmoudvand H, Fasihi Harandi M, Shakibaie M, Aflatoonian MR, ZiaAli N, Makki MS, Jahanbakhsh S. Scolicidal effects of biogenic selenium nanoparticles against protoscolices of hydatid cysts. Int J Surg. 2014;12:399–403. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Taylor DH, Morris DL. Combination chemotherapy is more effective in postspillage prophylaxis for hydatid disease than either albendazole or praziquantel alone. Br J Surg. 1989;76:954. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800760927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Balik AA, Başoğlu M, Celebi F, Oren D, Polat KY, Atamanalp SS, Akçay MN. Surgical treatment of hydatid disease of the liver: review of 304 cases. Arch Surg. 1999;134:166–169. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.134.2.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Utkan NZ, Cantürk NZ, Gönüllü N, Yildirir C, Dülger M. Surgical experience of hydatid disease of the liver: omentoplasty or capitonnage versus tube drainage. Hepatogastroenterology. 2001;48:203–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Katkhouda N, Fabiani P, Benizri E, Mouiel J. Laser resection of a liver hydatid cyst under videolaparoscopy. Br J Surg. 1992;79:560–561. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800790628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Bickel A, Daud G, Urbach D, Lefler E, Barasch EF, Eitan A. Laparoscopic approach to hydatid liver cysts. Is it logical? Physical, experimental, and practical aspects. Surg Endosc. 1998;12:1073–1077. doi: 10.1007/s004649900783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Baskaran V, Patnaik PK. Feasibility and safety of laparoscopic management of hydatid disease of the liver. JSLS. 2004;8:359–363. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Seven R, Berber E, Mercan S, Eminoglu L, Budak D. Laparoscopic treatment of hepatic hydatid cysts. Surgery. 2000;128:36–40. doi: 10.1067/msy.2000.107062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Eckert J. Alveolar echinococcosis (Echinococcus multilocularis) and other forms of echinococcosis (Echinococcus oligarthrus and Echinococcus vogeli) In: Palmer SR, Soulsby EJL, Simpson DIH, editors. Oxford Textbook of Zoonoses: Biology, Clinical Practice, and Public Health Control. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1998. pp. 689–716. [Google Scholar]

- 116.Sato N, Aoki S, Matsushita M, Uchino J. Clinical features. In: Uchino J, Sato N, editors. Alveolar echinococcosis of the liver. Sapporo: Hokkaido University School of Medicine; 1993. pp. 63–68. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Ammann RW, Eckert J. Cestodes. Echinococcus. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1996;25:655–689. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8553(05)70268-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Torgerson PR, Schweiger A, Deplazes P, Pohar M, Reichen J, Ammann RW, Tarr PE, Halkik N, Müllhaupt B. Alveolar echinococcosis: from a deadly disease to a well-controlled infection. Relative survival and economic analysis in Switzerland over the last 35 years. J Hepatol. 2008;49:72–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.McManus DP, Zhang W, Li J, Bartley PB. Echinococcosis. Lancet. 2003;362:1295–1304. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14573-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Bresson-Hadni S, Delabrousse E, Blagosklonov O, Bartholomot B, Koch S, Miguet JP, Mantion GA, Vuitton DA. Imaging aspects and non-surgical interventional treatment in human alveolar echinococcosis. Parasitol Int. 2006;55 Suppl:S267–S272. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2005.11.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Bartholomot G, Vuitton DA, Harraga S, Shi DZ, Giraudoux P, Barnish G, Wang YH, MacPherson CN, Craig PS. Combined ultrasound and serologic screening for hepatic alveolar echinococcosis in central China. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2002;66:23–29. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2002.66.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Reuter S, Nüssle K, Kolokythas O, Haug U, Rieber A, Kern P, Kratzer W. Alveolar liver echinococcosis: a comparative study of three imaging techniques. Infection. 2001;29:119–125. doi: 10.1007/s15010-001-1081-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Stumpe KD, Renner-Schneiter EC, Kuenzle AK, Grimm F, Kadry Z, Clavien PA, Deplazes P, von Schulthess GK, Muellhaupt B, Ammann RW, et al. F-18-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron-emission tomography of Echinococcus multilocularis liver lesions: prospective evaluation of its value for diagnosis and follow-up during benzimidazole therapy. Infection. 2007;35:11–18. doi: 10.1007/s15010-007-6133-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Kern P, Wen H, Sato N, Vuitton DA, Gruener B, Shao Y, Delabrousse E, Kratzer W, Bresson-Hadni S. WHO classification of alveolar echinococcosis: principles and application. Parasitol Int. 2006;55 Suppl:S283–S287. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2005.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Ma L, Ito A, Liu YH, Wang XG, Yao YQ, Yu DG, Chen YT. Alveolar echinococcosis: Em2plus-ELISA and Em18-western blots for follow-up after treatment with albendazole. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1997;91:476–478. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(97)90291-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Scheuring UJ, Seitz HM, Wellmann A, Hartlapp JH, Tappe D, Brehm K, Spengler U, Sauerbruch T, Rockstroh JK. Long-term benzimidazole treatment of alveolar echinococcosis with hematogenic subcutaneous and bone dissemination. Med Microbiol Immunol. 2003;192:193–195. doi: 10.1007/s00430-002-0171-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Gottstein B, Jacquier P, Bresson-Hadni S, Eckert J. Improved primary immunodiagnosis of alveolar echinococcosis in humans by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using the Em2plus antigen. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:373–376. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.2.373-376.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Ito A, Schantz PM, Wilson JF. Em18, a new serodiagnostic marker for differentiation of active and inactive cases of alveolar hydatid disease. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1995;52:41–44. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1995.52.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Wen H, Bresson-Hadni S, Vuitton DA, Lenys D, Yang BM, Ding ZX, Craig PS. Analysis of immunoglobulin G subclass in the serum antibody responses of alveolar echinococcosis patients after surgical treatment and chemotherapy as an aid to assessing the outcome. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1995;89:692–697. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(95)90449-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Wen H, Craig PS, Ito A, Vuitton DA, Bresson-Hadni S, Allan JC, Rogan MT, Paollilo E, Shambesh M. Immunoblot evaluation of IgG and IgG-subclass antibody responses for immunodiagnosis of human alveolar echinococcosis. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1995;89:485–495. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1995.11812981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Dreweck CM, Lüder CG, Soboslay PT, Kern P. Subclass-specific serological reactivity and IgG4-specific antigen recognition in human echinococcosis. Trop Med Int Health. 1997;2:779–787. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1997.d01-385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Wen H, Craig PS. Immunoglobulin G subclass responses in human cystic and alveolar echinococcosis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1994;51:741–748. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1994.51.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Ben Nouir N, Gianinazzi C, Gorcii M, Müller N, Nouri A, Babba H, Gottstein B. Isolation and molecular characterization of recombinant Echinococcus granulosus P29 protein (recP29) and its assessment for the post-surgical serological follow-up of human cystic echinococcosis in young patients. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2009;103:355–364. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Ben Nouir N, Nuñez S, Gianinazzi C, Gorcii M, Müller N, Nouri A, Babba H, Gottstein B. Assessment of Echinococcus granulosus somatic protoscolex antigens for serological follow-up of young patients surgically treated for cystic echinococcosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:1631–1640. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01689-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Buttenschoen K, Carli Buttenschoen D, Gruener B, Kern P, Beger HG, Henne-Bruns D, Reuter S. Long-term experience on surgical treatment of alveolar echinococcosis. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2009;394:689–698. doi: 10.1007/s00423-008-0392-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Kadry Z, Renner EC, Bachmann LM, Attigah N, Renner EL, Ammann RW, Clavien PA. Evaluation of treatment and long-term follow-up in patients with hepatic alveolar echinococcosis. Br J Surg. 2005;92:1110–1116. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Reuter S, Jensen B, Buttenschoen K, Kratzer W, Kern P. Benzimidazoles in the treatment of alveolar echinococcosis: a comparative study and review of the literature. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2000;46:451–456. doi: 10.1093/jac/46.3.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Reuter S, Buck A, Grebe O, Nüssle-Kügele K, Kern P, Manfras BJ. Salvage treatment with amphotericin B in progressive human alveolar echinococcosis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:3586–3591. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.11.3586-3591.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Stettler M, Fink R, Walker M, Gottstein B, Geary TG, Rossignol JF, Hemphill A. In vitro parasiticidal effect of Nitazoxanide against Echinococcus multilocularis metacestodes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:467–474. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.2.467-474.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Kern P, Abboud P, Kern W, Stich A, Bresson-Hadni S, Guerin B, Buttenschoen K, Gruener B, Reuter S, Hemphill A. Critical appraisal of nitazoxanide for the treatment of alveolar echinococcosis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;79:119. [Google Scholar]

- 141.Ammann RW, Hirsbrunner R, Cotting J, Steiger U, Jacquier P, Eckert J. Recurrence rate after discontinuation of long-term mebendazole therapy in alveolar echinococcosis (preliminary results) Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1990;43:506–515. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1990.43.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Wilson JF, Rausch RL, McMahon BJ, Schantz PM. Parasiticidal effect of chemotherapy in alveolar hydatid disease: review of experience with mebendazole and albendazole in Alaskan Eskimos. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;15:234–249. doi: 10.1093/clinids/15.2.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Ammann RW, Fleiner-Hoffmann A, Grimm F, Eckert J. Long-term mebendazole therapy may be parasitocidal in alveolar echinococcosis. J Hepatol. 1998;29:994–998. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(98)80129-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Ishizu H, Uchino J, Sato N, Aoki S, Suzuki K, Kuribayashi H. Effect of albendazole on recurrent and residual alveolar echinococcosis of the liver after surgery. Hepatology. 1997;25:528–531. doi: 10.1002/hep.510250305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Ammann RW, Ilitsch N, Marincek B, Freiburghaus AU. Effect of chemotherapy on the larval mass and the long-term course of alveolar echinococcosis. Swiss Echinococcosis Study Group. Hepatology. 1994;19:735–742. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840190328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Krige J, Bornman J. C, Belghiti J. Hydatid disease of the liver. In: Belghiti J, Büchler MW, Chapman WC, D'Angelica MI, DeMatteo RP, et al., editors. Blumgart's Surgery of the Liver, Biliary Tract and Pancreas. Philadelphia: Elsevier Sounders; 2012. p. 1050. [Google Scholar]