Abstract

BACKGROUND

Increased endothelin (ET)-1 expression causes endothelial dysfunction and oxidative stress. Plasma ET-1 is increased in patients with diabetes mellitus. Since endothelial dysfunction often precedes vascular complications in diabetes, we hypothesized that overexpression of ET-1 in the endothelium would exaggerate diabetes-induced endothelial dysfunction.

METHODS

Diabetes was induced by streptozotocin treatment (55mg/kg/day, i.p.) for 5 days in 6-week-old male wild type (WT) mice and in mice overexpressing human ET-1 restricted to the endothelium (eET-1). Mice were studied 14 weeks later. Small mesenteric artery (MA) endothelial function and vascular remodeling by pressurized myography, reactive oxygen species (ROS) production by dihydroethidium staining and mRNA expression by reverse transcription/quantitative PCR were determined.

RESULTS

Endothelium-dependent vasodilatory responses to acetylcholine of MA were reduced 24% by diabetes in WT (P < 0.05), and further decreased by 12% in eET-1 (P < 0.05). Diabetes decreased MA media/lumen in WT and eET-1 (P < 0.05), whereas ET-1 overexpression increased MA media/lumen similarly in diabetic and nondiabetic WT mice (P < 0.05). Vascular ROS production was increased 2-fold by diabetes in WT (P < 0.05) and further augmented 1.7-fold in eET-1 (P < 0.05). Diabetes reduced endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS, Nos3) expression in eET-1 by 31% (P < 0.05) but not in WT. Induction of diabetes caused a 52% (P < 0.05) increase in superoxide dismutase 1 (Sod1) and a 32% (P < 0.05) increase in Sod2 expression in WT but not in eET-1.

CONCLUSIONS

Increased expression of ET-1 exaggerates diabetes-induced endothelial dysfunction. This may be caused by decrease in eNOS expression, increase in vascular oxidative stress, and decrease in antioxidant capacity.

Keywords: blood pressure, endothelium, hypertension, resistance arteries, vascular remodeling.

The prevalence of diabetes mellitus among adults is increasing worldwide and is projected to increase from the estimated 135 million affected in 1995 to 300 million by 2025.1 The major cause of mortality in diabetic patients is vascular disease,2 which includes macroangiopathy (atherosclerosis) and microangiopathy (leading to nephropathy, neuropathy, retinopathy). Endothelial dysfunction, characterized by a reduction in the bioavailability of the vasodilating nitric oxide (NO), is a common finding in diabetes and participates in the onset of diabetes-related vascular disease. Although the exact cause of endothelial dysfunction in diabetes is complex, overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) is believed to play an important role.

Endothelin (ET)-1 is a potent vasoconstrictor peptide produced by endothelial cells3 that participates in cardiovascular disease by causing vascular injury. Circulating levels of ET-1 are increased in patients with diabetes mellitus and may contribute to diabetes-related endothelial dysfunction.4–6 Chronic oral treatment with bosentan, a dual ET receptor antagonist, improved endothelial function in patients with type-2 diabetes and microalbuminuria.7 In streptozotocin (STZ)-treated rats, dual ET receptor blockade with J-104132 improved type-1 diabetes-induced aortic endothelial dysfunction.8 Vascular overproduction of ET-1 in diabetes could cause endothelial dysfunction through generation of oxidative stress. Indeed, transgenic mice overexpressing ET-1 selectively in the endothelium (eET-1) present endothelial dysfunction and vascular remodeling that is associated with enhanced reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase activity.9

The goal of the current study was to determine whether increased levels of ET-1 participate in diabetes-induced vascular injury. We hypothesized that endothelium-restricted overexpression of ET-1 would exaggerate type-1 diabetes-induced endothelial dysfunction by increasing oxidative stress.

METHODS

Detailed Materials and Methods are available in the Supplementary Data.

Experimental design

The study was approved by the Animal Care Committee of the Lady Davis Institute for Medical Research and McGill University and followed recommendations of the Canadian Council for Animal Care. Transgenic mice constitutively overexpressing human ET-1 selectively in endothelial cells (eET-1) were previously described.9 Six week-old male C57BL/6 wild-type (WT) mice or eET-1 mice were injected intraperitoneally with either vehicle (sodium citrate buffer) or with STZ (55mg/kg/day) for 5 consecutive days to induce type-1 diabetes mellitus. Ten days after the last injection of STZ, only mice presenting a blood glucose level ≥15 mmol/l after 4–6 hours of fasting were included in the study. Fourteen weeks after the last intraperitoneal injection of either vehicle or STZ, mice were weighed, anesthetized with isoflurane, and tissues were collected. Blood was collected by cardiac puncture on EDTA and plasma stored at −80 °C until used for ET-1 determination by ELISA (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). The mesenteric artery (MA) vascular bed was dissected, and other tissues and tibia harvested in ice-cold phosphate buffered saline. Tissues were weighed and tibia length measured. Second-order small MA were used for assessment of endothelial function and vessel mechanics by pressurized myography. Segments of MA were embedded in Clear Frozen Section Compound (VWR International, Edmonton, Canada) for determination of ROS generation with the ROS-sensitive fluorescent dye dihydroethidium. For the study of mRNA expression, the MA arcade was dissected away from the attached intestine under RNase-free conditions and stored immediately in RNAlater (Life Technologies, Burlington, Canada) until RNA extraction. The mRNA expression of endothelial NO synthase (eNOS, Nos3), inducible NO synthase (iNOS, Nos2), ETA receptor (Ednra), ETB receptor (Ednrb), superoxide dismutase 1 (Sod1), Sod2 (Sod2), Sod3 (Sod3), NADPH oxidase 1 (Nox1), Nox4 (Nox4), arginase 2 (Arg2), and ribosomal protein S16 (Rps16) was determined in MA by reverse transcription/quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR with oligonucleotides mentioned in Supplemental Table S1).

Data analysis

Results are presented as means ± SEM. Two-way analysis of variance for repeated measurements evaluated differences among groups in concentration-response curves. Differences in the maximal responses to norepinephrine were evaluated between concentrations of 10–5 and 10–4 mol/l. Differences in the response to acetylcholine were evaluated between concentrations of 10–6 to 10–4 mol/l. All other results were compared using 2-way analysis of variance followed by a Student–Newman–Keuls post-hoc test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Effects of type-1 diabetes on WT and eET-1 mice body and tissue weights

Induction of type-1 diabetes resulted in similar decrease in body weight in WT and eET-1 mice (Supplemental Table S2, P < 0.05). In contrast, tibia length was only slightly reduced in STZ-treated eET-1 mice (P < 0.05). Fasting glycemia prior to sacrifice was increased ~1.6-fold (P < 0.05) in diabetic WT mice, which was slightly reduced by ET-1 overexpression (P < 0.05). Induction of type-1 diabetes decreased heart weight and increased kidney weight to a similar extent in WT and eET-1 mice (P < 0.05). Type-1 diabetes was associated with increased liver weight in WT mice (P < 0.05), which was further exaggerated in diabetic eET-1 mice (P < 0.05). Lung and spleen weights were unaffected by either type-1 diabetes or ET-1 overexpression.

Type-1 diabetes did not alter plasma ET-1 level in WT mice, but reduced it in eET-1 mice

As we previously described,9 plasma ET-1 level was increased 9-fold (P < 0.05) in eET-1 compared to WT mice (Supplemental Figure S1A). Induction of type-1 diabetes did not alter plasma ET-1 level in WT mice, whereas plasma ET-1 was reduced in eET-1 mice compared to nondiabetic eET-1 mice (P < 0.05). Since the eET-1 mice overexpress human ET-1 under the transcriptional control of the endothelium-specific angiopoietin-1 receptor (Tek, also known as Tie2) promoter, we investigated the mRNA expression of Tie2 in mesenteric arteries. Induction of type-1 diabetes reduced Tie2 expression (P < 0.05) in eET-1 mice but not WT mice (Supplemental Figure S1B).

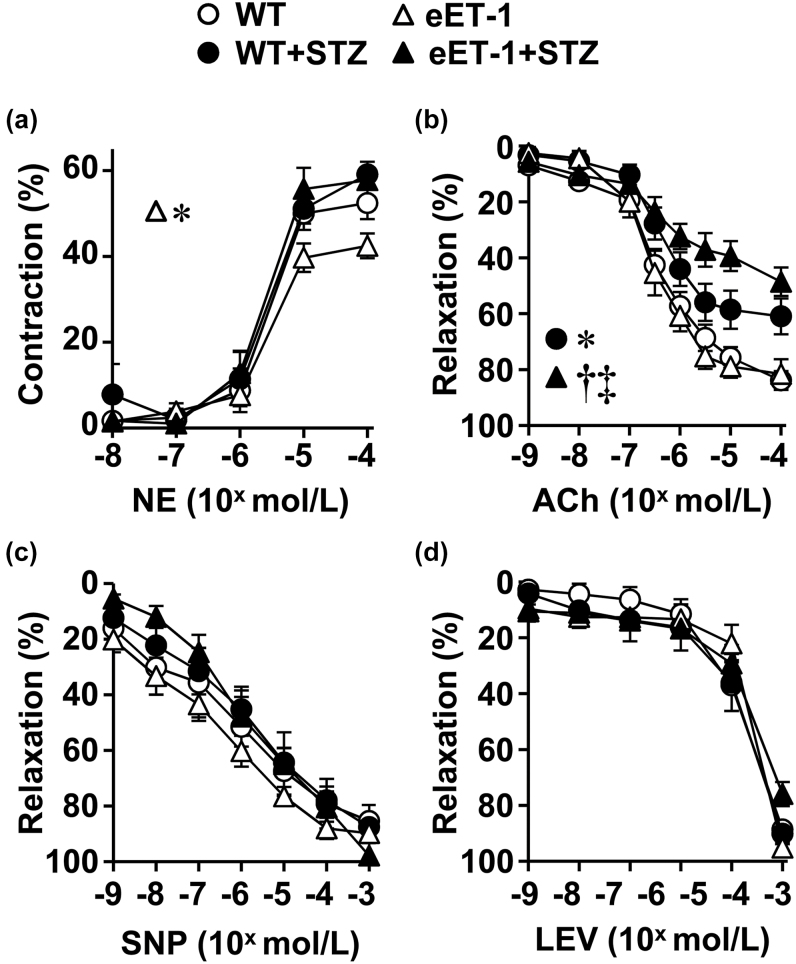

ET-1 overexpression exaggerated diabetes-induced impairment of endothelium-dependent relaxation

The maximal vasoconstrictor response of MA to norepinephrine was reduced only in nondiabetic eET-1 mice (Figure 1A). WT and eET-1 mice presented similar MA relaxation responses to acetylcholine. Induction of type-1 diabetes reduced endothelium-dependent relaxation by 24% (P < 0.05) in WT mice compared to control WT mice (Figure 1B), which was further impaired by 12% (P < 0.05) in diabetic eET-1 mice. In contrast, MA relaxation to the exogenous NO donor sodium nitroprusside (Figure 1C) and the ATP-sensitive K+ channel opener levcromakalim (Figure 1D) were similar in the 4 groups. RT-qPCR analysis demonstrated an increase in Nos3 (eNOS) gene expression in MA of vehicle-treated eET-1 compared with WT (Figure 4A). The induction of type-1 diabetes reduced the expression of Nos3 in the MA of diabetic eET-1 mice (P < 0.05) but did not affect expression of Nos3 in the MA of diabetic WT (Figure 4A).

Figure 1.

ET-1 overexpression exaggerated the diabetes-induced impairment of endothelium-dependent relaxation. Contractile responses to norepinephrine (NE, a), endothelium-dependent relaxation responses to acetylcholine (ACh, b), and endothelium-independent relaxation responses to sodium nitroprusside (SNP, c) or levcromakalim (LEV, d) were determined in small mesenteric arteries of wild type and eET-1 mice 14 weeks after treatment with either vehicle or streptozotocin. Relaxation responses are % increases in lumen diameter after NE precontraction. Values are means ± SEM, n = 6–9. Differences in the maximal responses to norepinephrine were evaluated between concentrations of 10−5 and 10−4 mol/l. Differences in the response to acetylcholine were evaluated between concentrations of 10−6 to 10−4 mol/l. *P < 0.05 vs. WT, †P < 0.01 vs. eET-1, and ‡P < 0.05 vs. WT + STZ. Abbreviations: eET-1, mice overexpressing human ET-1 restricted to endothelium; STZ, streptozotocin; WT, wild type.

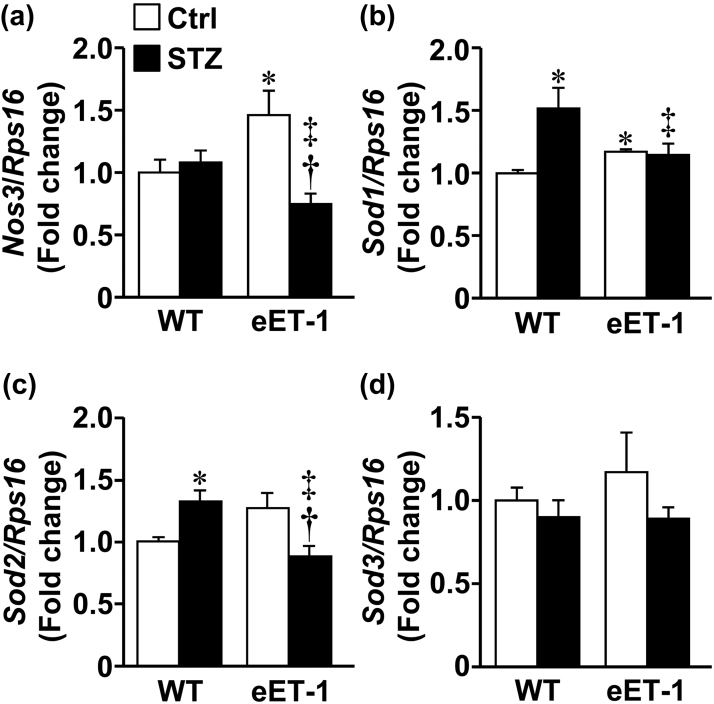

Figure 4.

ET-1 overexpression blunted type-1 diabetes-induced upregulation of superoxide dismutase 1 and 2 mRNA expression in small mesenteric arteries. The gene expression of Nos3 (or eNOS: endothelial nitric oxide synthase, a), superoxide dismutase 1 (Sod1, b), Sod2 (c), Sod3 (d), and ribosomal protein S16 (Rps16) mRNAs was determined in small mesenteric arteries of wild type and eET-1 mice 14 weeks after treatment with either vehicle or streptozotocin. Data are presented as means ± SEM, n = 5–7. *P < 0.05 vs. WT, †P < 0.05 vs. eET-1, and ‡P < 0.05 vs. WT + STZ. Abbreviations: eET-1, mice overexpressing human ET-1 restricted to endothelium; STZ, streptozotocin; WT, wild type.

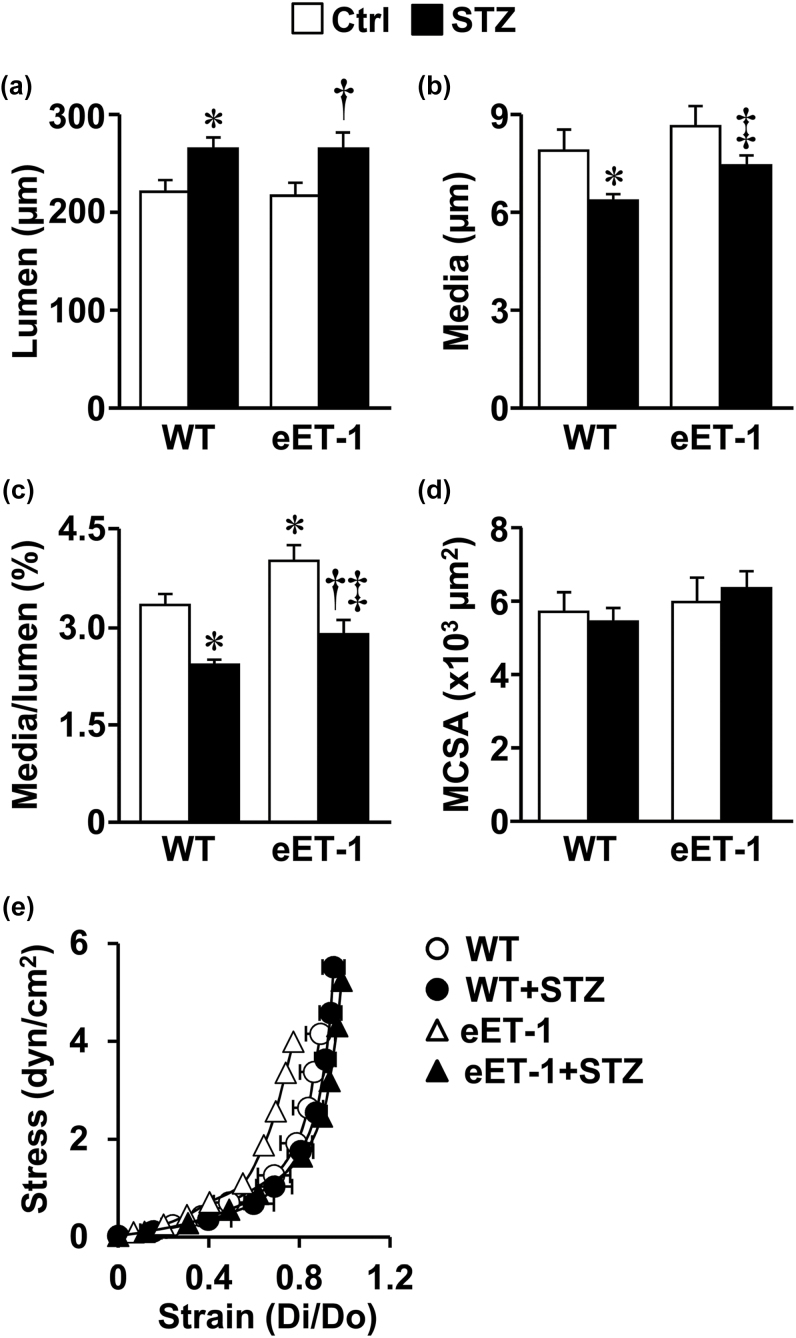

Effects of type-1 diabetes on MA remodeling and stiffness in WT and eET-1 mice

Induction of type-1 diabetes was associated with increased MA lumen (Figure 2A), decreased MA wall thickness (Figure 2B) and MA media/lumen ratio (Figure 2C) in both WT and eET-1 mice (P < 0.05). ET-1 overexpression increased MA media/lumen ratio by 20% (P < 0.05) in both vehicle-treated and STZ-treated WT mice (Figure 3C). The media cross-sectional area and the MA stress-strain curves were unaffected by either type-1 diabetes or by ET-1 overexpression (Figure 2E).

Figure 2.

Effects of type-1 diabetes on MA remodeling and stiffness in wild type and eET-1 mice. Lumen (a), media (b), media/lumen (c) and media cross-sectional area (d) at 45mm Hg, and stress-strain relationship (e) were determined in small mesenteric arteries of WT and eET-1 mice 14 weeks after treatment with either vehicle or streptozotocin. Values are means ± SEM, n = 6–9. *P < 0.05 vs. WT, †P < 0.05 vs. eET-1, and ‡P < 0.05 vs. WT + STZ. Abbreviations: eET-1, mice overexpressing human ET-1 restricted to endothelium; MA, mesenteric arteries; STZ, streptozotocin; WT, wild type.

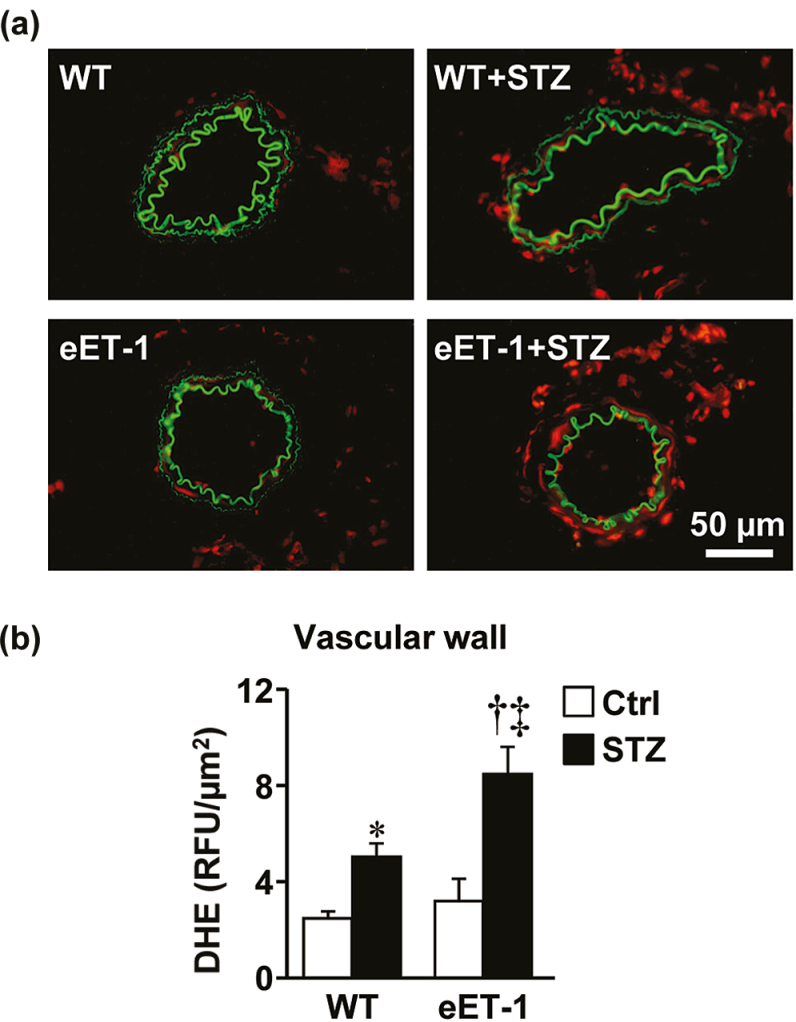

Figure 3.

ET-1 overexpression exaggerated type-1 diabetes-induced oxidative stress in small mesenteric arteries. Reactive oxygen species generation was determined (a and b) by dihydroethidium (DHE) staining (relative fluorescence units) in small mesenteric arteries of wild type and eET-1 mice 14 weeks after treatment with either vehicle or streptozotocin. Representative DHE-stained sections (a) of mesenteric arteries from 4–6 mice per group are presented. Data are presented as means ± SEM, n = 4–6. *P < 0.05 vs. WT, †P < 0.001 vs. eET-1, and ‡P < 0.05 vs. WT + STZ. Abbreviations: eET-1, mice overexpressing human ET-1 restricted to endothelium; REPETITION HERE; STZ, streptozotocin; WT, wild type.

ET-1 overexpression exaggerated type-1 diabetes-induced vascular oxidative stress

Vascular ROS production was assessed in MA by dihydroethidium staining. Induction of type-1 diabetes was associated with a doubling of dihydroethidium staining within the MA wall of WT mice (P < 0.05), which was further exacerbated in diabetic eET-1 mice (P < 0.05). Type-1 diabetes was associated with increased mRNA expression of antioxidant enzymes Sod1 (50%, P < 0.05) and Sod2 (30%, P < 0.05) in the MA of WT mice compared with vehicle-treated WT (Figure 4B–C), whereas no effect was observed in diabetic eET-1. Type-1 diabetes reduced the expression of Sod2 by 30% (P < 0.05) in the MA of eET-1 mice when compared to vehicle-treated eET-1 mice (Figure 4C). The mRNA expression of pro-oxidant enzymes Nos2 (iNOS), Nox1 and Nox4 were unaffected by either type-1 diabetes or ET-1 overexpression (Supplemental Figure S2B–D).

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated that endothelial ET-1 overexpression exaggerates type-1 diabetes-induced endothelial dysfunction by enhancing oxidative stress. Indeed, diabetic mice overexpressing ET-1 exhibited enhanced vascular oxidative stress and decreased expression of antioxidant enzymes.

Although vascular disease constitutes the major cause of mortality in patients with diabetes, the mechanisms leading to impaired vascular function are incompletely understood. Hyperglycemia alone can decrease NO bioavailability by increasing ROS production and through protein kinase C-dependent eNOS downregulation. Interestingly, plasma levels of ET-1 are increased in diabetes4,5 and blockade of ET receptors improves endothelial function in patients with type-2 diabetes and microalbuminuria.7 Vascular overproduction of ET-1 may therefore contribute to vascular abnormalities in diabetes. To test this hypothesis, we studied transgenic mice which overexpress ET-1 selectively in endothelial cells using a traditional model of type-1 diabetes induced by STZ treatment.

Induction of type-1 diabetes reduced body weight to a similar extent in WT and eET-1 mice. It increased fasting glycemia 1.6-fold in WT mice, which was slightly reduced by ET-1 overexpression but nevertheless maintained at diabetic levels. Importantly, this indicates that the enhanced vascular injury observed in diabetic eET-1 mice is not due to an exaggeration in fasting glycemia. The reduction in glycemia may be a result of enhanced glucose uptake in peripheral tissues, as ET-1 increases glucose uptake through stimulation of GLUT4 translocation in adipocytes.10

In the current study, induction of diabetes did not increase plasma ET-1 levels in WT mice. It is possible that the duration of diabetes was not sufficiently long to increase ET-1 levels. Alternatively, plasma levels may have increased transiently and returned to levels similar to nondiabetic mice. Indeed, Hopfner et al.11 have shown that plasma ET-1 levels in STZ-treated rodents vary depending on duration of diabetes. ET-1 overexpression increased plasma ET-1 level 9-fold in WT mice, which was reduced by type-1 diabetes. Since the eET-1 mice overexpress human ET-1 under the transcriptional control of the Tie2 promoter, we investigated MA mRNA expression of Tie2. A reduction of Tie2 expression in eET-1 mice but not WT mice by type-1 diabetes may explain in part the alteration in ET-1 levels. Notwithstanding, plasma ET-1 levels are 8-fold higher in diabetic eET-1 mice when compared to diabetic WT mice, which is consistent with ET-1 overexpression exaggerating diabetes-induced vascular injury. Liver weight was increased by diabetes, which was further increased in diabetic eET-1 mice. Increases in liver weight have previously been described in STZ diabetic mice and have been ascribed to increased accumulation of fat within hepatocytes.12 ET-1 overexpression may therefore worsen liver injury by increasing fat uptake or by stimulating fibrosis.

Endothelial dysfunction is a common finding in diabetes and is thought to participate in the onset of diabetes-related vascular disease. In this study, we found that type-1 diabetes reduced MA endothelium-dependent relaxation to acetylcholine in WT mice, which was further exaggerated by ET-1 overexpression. The impairment in vasorelaxation was not due to a defect in smooth muscle function, as endothelium-independent relaxations to the NO donor sodium nitroprusside and the K+ channel opener levcromakalim were similar in all groups. Using an organ-culture system, Kamata et al.13 have previously demonstrated that prolonged incubation of aorta from diabetic rats with ET-1 worsens endothelial dysfunction. We have extended these findings by demonstrating that in vivo overexpression of ET-1 exaggerated diabetes-induced endothelial dysfunction in small resistance arteries. We next investigated whether the impairment in endothelial function was due to reduced production of vasodilating factors. We evaluated eNOS expression since endothelial cells promote vasodilation mainly through the release of eNOS-derived NO. We found that diabetes decreased MA eNOS mRNA expression by >30% in eET-1 but not WT mice. In contrast, eNOS expression was increased in vehicle-treated eET-1 mice compared to WT. Reduced eNOS expression in diabetic mice overexpressing ET-1 is likely to contribute to their exaggerated endothelial dysfunction whereas increased eNOS expression in vehicle-treated eET-1 mice may explain the absence of endothelial dysfunction in these mice. It is currently unclear why nondiabetic eET-1 mice present increased MA eNOS expression. This may be a result of genetic drift, as these transgenic mice were generated many years ago and may have adopted a slightly different phenotype over the years. Arg2 also contributes to endothelial dysfunction in cardiovascular disease by competing with eNOS for its substrate l-arginine.14 We did not however find any changes in Arg2 expression between groups.

In addition to changes in endothelial function, diabetes is associated with alterations in vascular morphology. Small resistance arteries from patients with type-2 diabetes undergo hypertrophic vascular remodeling, as indicated by an increase in both media/lumen ratio and media cross-sectional area.15,16 In rats, STZ-induced diabetes has been associated with resistance artery hypertrophic inward remodeling17,18 and eutrophic outward remodeling.19 Interestingly, selective ETA20,21 or dual ETA/B18 receptor blockade reduces diabetes-induced vascular hypertrophy of resistance arteries in rodents, suggesting that ET-1 contributes to diabetes-associated vascular remodeling. In the current study, ET-1 overexpression increased media/lumen ratio to a similar degree in vehicle- and STZ-treated mice without affecting media cross-sectional area. In contrast, type-1 diabetes decreased MA media/lumen ratio in both WT and eET-1 mice. It is possible that the changes in media/lumen ratio caused by diabetes are a result of the protein catabolism that follows 14 weeks of insulin deficit. Accordingly, ET-1-induced vascular remodeling would be offset by alterations in energy and protein metabolism.

ET-1 mediates its actions through stimulation of ETA and ETB receptors. ETA receptors are found on vascular smooth muscle cells whereas ETB receptors are found on endothelial cells but also smooth muscle cells under pathophysiological conditions. Activation of smooth muscle cell ETA and ETB receptors causes vasoconstriction, whereas activation of endothelial cell ETB receptors causes vasodilation mainly through release of NO. ETB receptors also mediate clearance of circulating ET-1 in the lung, liver, and kidney. In experimental models of diabetes, resistance artery expression of ETA and ETB is increased and vessel contractility to ET-1 is enhanced.22,23 In the current study, diabetes increased MA ETB expression and tended to increase MA ETA receptor expression. Although this change is observed in MA, a similar increase in pulmonary endothelial ETB clearance receptors could have contributed to the absence of changes in plasma ET-1 levels in diabetic WT mice. ET-1 overexpression increased expression of both receptors only in nondiabetic mice. Thus, the enhancement of diabetes-induced vascular injury by ET-1 overexpression is not mediated by an upregulation of ETA receptors.

Oxidative stress, defined as an imbalance between ROS generation and inactivation, plays an important role in the pathophysiology of vascular disease. Excess ROS production impairs endothelial function by reducing NO bioavailability and promotes vascular remodeling by enhancing cell proliferation and hypertrophy.24 In this study, induction of type-1 diabetes increased ROS production within the MA wall of WT mice, which was further exaggerated by ET-1 overexpression. Enhanced ROS production in diabetic eET-1 mice is likely to have contributed to the exaggerated endothelial dysfunction. As ROS production was detected by dihydroethidium staining, it is also impossible to distinguish between cytosolic superoxide and peroxynitrite anion. We investigated the expression of pro-oxidant enzymes such as NADPH oxidases 1 and 4 as well as iNOS but did not find any differences between groups. Superoxide dismutases catalyze the dismutation of superoxides into oxygen and hydrogen peroxide and as such contribute to the antioxidant capacity of cells. We found indeed that type-1 diabetes increased MA Sod1 and Sod2 expression, which may serve as a compensatory mechanism to counteract increased ROS generation. Interestingly, diabetes did not increase SOD expression in eET-1 mice but actually decreased Sod2. Thus, increased production of endothelial ET-1 impairs antioxidant capacity within the vasculature, resulting in excess ROS.

In conclusion, these results demonstrate that vascular overproduction of ET-1 exaggerates type-1 diabetes-induced endothelial dysfunction. This is mediated by decreased eNOS expression, decreased antioxidant capacity, and enhanced ROS production. Type-1 diabetic patients with elevated plasma ET-1 levels may therefore be at greater risk of developing vascular disease.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary materials are available at American Journal of Hypertension (http://ajh.oxfordjournals.org).

DISCLOSURE

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Adriana Cristina Ene and Guillem Colell Dinarès for excellent technical support and animal care. This work was supported by Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) grants 37917 and 102606, a CIHR First Pilot Foundation Grant, a Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation Grant number 4-2010-528 on NOX-derived ROS: Renal and Vascular Complications of Type-1 Diabetes, a Canada Research Chair (CRC) on Hypertension and Vascular Research by the CRC Government of Canada/CIHR Program and by the Canada Fund for Innovation (CFI), all to E.L.S., and by fellowships to N.I.K. (SQHA and “Fonds de recherche du Québec en Santé”), S.O. (CIHR Canada Graduate Scholarship-Master’s scholarship), M.O.R.M. (Canadian Vascular Network and Lady Davis Institute/TD Bank studentship), and T.B. (Société québécoise d’hypertension artérielle (SQHA) and Richard and Edith Strauss Postdoctoral Fellowship).

REFERENCES

- 1. Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, Sicree R, King H. Global prevalence of diabetes: estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030. Diabetes Care 2004; 27:1047–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Morrish NJ, Wang SL, Stevens LK, Fuller JH, Keen H. Mortality and causes of death in the WHO Multinational Study of Vascular Disease in Diabetes. Diabetologia 2001; 44(Suppl 2):S14–S21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yanagisawa M, Kurihara H, Kimura S, Tomobe Y, Kobayashi M, Mitsui Y, Yazaki Y, Goto K, Masaki T. A novel potent vasoconstrictor peptide produced by vascular endothelial cells. Nature 1988; 332:411–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schneider JG, Tilly N, Hierl T, Sommer U, Hamann A, Dugi K, Leidig-Bruckner G, Kasperk C. Elevated plasma endothelin-1 levels in diabetes mellitus. Am J Hypertens 2002; 15:967–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Takahashi K, Ghatei MA, Lam HC, O’Halloran DJ, Bloom SR. Elevated plasma endothelin in patients with diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 1990; 33:306–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Collier A, Leach JP, McLellan A, Jardine A, Morton JJ, Small M. Plasma endothelinlike immunoreactivity levels in IDDM patients with microalbuminuria. Diabetes Care 1992; 15:1038–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rafnsson A, Böhm F, Settergren M, Gonon A, Brismar K, Pernow J. The endothelin receptor antagonist bosentan improves peripheral endothelial function in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and microalbuminuria: a randomised trial. Diabetologia 2012; 55:600–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kanie N, Kamata K. Effects of chronic administration of the novel endothelin antagonist J-104132 on endothelial dysfunction in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat. Br J Pharmacol 2002; 135:1935–1942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Amiri F, Virdis A, Neves MF, Iglarz M, Seidah NG, Touyz RM, Reudelhuber TL, Schiffrin EL. Endothelium-restricted overexpression of human endothelin-1 causes vascular remodeling and endothelial dysfunction. Circulation 2004; 110:2233–2240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wu-Wong JR, Berg CE, Wang J, Chiou WJ, Fissel B. Endothelin stimulates glucose uptake and GLUT4 translocation via activation of endothelin ETA receptor in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. J Biol Chem 1999; 274:8103–8110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hopfner RL, McNeill JR, Gopalakrishnan V. Plasma endothelin levels and vascular responses at different temporal stages of streptozotocin diabetes. Eur J Pharmacol 1999; 374:221–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kume E, Ohmachi Y, Itagaki S, Tamura K, Doi K. Hepatic changes of mice in the subacute phase of streptozotocin (SZ)-induced diabetes. Exp Toxicol Pathol 1994; 46:368–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kamata K, Kanie N, Matsumoto T, Kobayashi T. Endothelin-1-induced impairment of endothelium-dependent relaxation in aortas isolated from controls and diabetic rats. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 2004; 44(Suppl 1):S186–S190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Toque HA, Tostes RC, Yao L, Xu Z, Webb RC, Caldwell RB, Caldwell RW. Arginase II deletion increases corpora cavernosa relaxation in diabetic mice. J Sex Med 2011; 8:722–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rizzoni D, Porteri E, Guelfi D, Muiesan ML, Valentini U, Cimino A, Girelli A, Rodella L, Bianchi R, Sleiman I, Rosei EA. Structural alterations in subcutaneous small arteries of normotensive and hypertensive patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Circulation 2001; 103:1238–1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schofield I, Malik R, Izzard A, Austin C, Heagerty A. Vascular structural and functional changes in type 2 diabetes mellitus: evidence for the roles of abnormal myogenic responsiveness and dyslipidemia. Circulation 2002; 106:3037–3043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cooper ME, Rumble J, Komers R, Du HC, Jandeleit K, Chou ST. Diabetes-associated mesenteric vascular hypertrophy is attenuated by angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition. Diabetes 1994; 43:1221–1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gilbert RE, Rumble JR, Cao Z, Cox AJ, van Eeden P, Allen TJ, Kelly DJ, Cooper ME. Endothelin receptor antagonism ameliorates mast cell infiltration, vascular hypertrophy, and epidermal growth factor expression in experimental diabetes. Circ Res 2000; 86:158–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Crijns FR, Wolffenbuttel BH, De Mey JG, Struijker Boudier HA. Mechanical properties of mesenteric arteries in diabetic rats: consequences of outward remodeling. Am J Physiol 1999; 276:H1672–H1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Harris AK, Hutchinson JR, Sachidanandam K, Johnson MH, Dorrance AM, Stepp DW, Fagan SC, Ergul A. Type 2 diabetes causes remodeling of cerebrovasculature via differential regulation of matrix metalloproteinases and collagen synthesis: role of endothelin-1. Diabetes 2005; 54:2638–2644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sachidanandam K, Portik-Dobos V, Harris AK, Hutchinson JR, Muller E, Johnson MH, Ergul A. Evidence for vasculoprotective effects of ETB receptors in resistance artery remodeling in diabetes. Diabetes 2007; 56:2753–2758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kelly-Cobbs AI, Harris AK, Elgebaly MM, Li W, Sachidanandam K, Portik-Dobos V, Johnson M, Ergul A. Endothelial endothelin B receptor-mediated prevention of cerebrovascular remodeling is attenuated in diabetes because of up-regulation of smooth muscle endothelin receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2011; 337:9–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Matsumoto T, Yoshiyama S, Kobayashi T, Kamata K. Mechanisms underlying enhanced contractile response to endothelin-1 in diabetic rat basilar artery. Peptides 2004; 25:1985–1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Touyz RM, Schiffrin EL. Reactive oxygen species in vascular biology: implications in hypertension. Histochem Cell Biol 2004; 122: 339–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.