Abstract

Laparoscopic resection for colon and rectal cancer is associated with quicker return of bowel function, reduced postoperative morbidity rates and shorter length of hospital stay compared to open surgery, with no differences in long-term survival. Conversion to open surgery is reported in up to 30% of patients enrolled in randomized control trials comparing open and laparoscopic colorectal resection for cancer. In this review, reasons for conversion are anatomical-related factors, disease-related-factors and surgeon-related factors. Body mass index, local tumour extension and co-morbidities are independent predictors of conversion. The current evidence has shown that patients with converted resection for colon cancer have similar outcomes compared to patients undergoing a laparoscopic completed or open resection. The few studies that have assessed the outcomes after conversion of laparoscopic rectal resection reported significantly higher rates of complications and longer length of hospital stay in converted patients compared to laparoscopically treated patients. No definitive conclusions can be drawn when converted and open rectal resections are compared. Early and pre-emptive conversion appears to have more favourable outcomes than reactive conversion; however, further large studies are needed to better define the optimal timing of conversion. With regard to long-term oncologic outcome, overall and disease-free survival in the case of conversion in laparoscopic colorectal cancer surgery seems to be worse than those achieved in patients in whom resection was successfully completed by laparoscopy. Although a worse long-term oncologic outcome has been suggested, it remains difficult to draw a proper conclusion due to the heterogeneity of the long-term outcomes as well as the inclusion of both colon and rectal cancer patients in most of the studies. Therefore, we discuss the currently available evidence of the impact of conversion in laparoscopic resection for colon and rectal cancer on both short-term outcomes and long-term survival.

Keywords: Conversion, Laparoscopy, Open surgery, Colon cancer, Rectal cancer, Morbidity, Mortality, Predictors, Recurrence, Survival

Core tip: Several randomized controlled trials have reported the short-term advantages of laparoscopic resection compared to open resection for both colon and rectal cancer. In addition, there is evidence showing the non-inferiority of the laparoscopic approach in colon and rectal cancer surgery in long-term survival. Conversion to open surgery has been reported in up to 30% of laparoscopic colorectal cancer resections. However, both short and long-term outcomes in these patients are unclear. Therefore, we discuss the currently available evidence of the impact of conversion of laparoscopic resection for colon and rectal cancer on both short-term outcomes and long-term survival.

INTRODUCTION

Since its introduction in the early nineties[1], laparoscopic resection for colorectal cancer has increasingly gained popularity[2]. Large randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have proved several short-term advantages of this approach, such as less intraoperative blood loss, sooner return to bowel function and shorter hospital stay[3-5] and similar long-term oncologic when compared with open surgery[6-11].

Conversion of laparoscopic colorectal resection to open surgery has been reported in up to 30% of patients enrolled in these RCTs. However, converted patients were mostly analyzed in the laparoscopic group on an “intention-to-treat” basis. The evidence coming from the non-randomized studies that have specifically assessed the impact of conversion on both short-term and long-term outcomes (i.e., local recurrence rate and overall and disease-free survival) is controversial[12-29]. The vast majority of these studies only included a limited number of patients and did not analyze colon and rectal cancer patients separately. As a consequence, the real influence of conversion on both short-term outcomes and long-term survival outcome in colorectal cancer patients is still unclear.

The aim of this review was to summarize all the available literature with regard to the short and long-term outcome in patients who were converted during laparoscopic resection for both colon and rectal cancer and to compare these outcomes with the results in patients in whom resection was successfully completed by laparoscopy.

LITERATURE SEARCH AND STUDY SELECTION

A search strategy of the literature was independently performed by two reviewers (Allaix ME and Furnée EJB) in MEDLINE, using the Pubmed search engine. The following search terms in title and abstract were used as free text words and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH): “colon”, “rectum”, “colorectal”, “rectal”, “conversion”, “cancer”, “laparoscopy” and “laparoscopic”. The literature search was performed for all years, up to March 2016. The studies identified by the search strategy were subsequently selected based on title, abstract and full-text by two independent reviewers (Allaix ME and Furnée EJB).

DATA ACQUISITION

Data of the included studies were independently acquired by two reviewers using a standard data extraction form. The study design, number of total, laparoscopic and converted patients, sex ratio, age, body mass index and preoperative (chemo)radiation in rectal cancer patients were extracted from the individual studies. Collected intra-operative data included type of colorectal resection, reason for conversion, amount of blood loss and operative time. With regard to short-term outcome parameters, the number and type of postoperative complications, mortality rate, postoperative transfusion rate, time to return to bowel function, reoperation and readmission rate and hospital stay were collected. Based on the histological assessment of the colorectal specimen, tumor size, number of lymph nodes, presence of a positive resection margin and tumor staging according to TNM classification as well as disease stage were extracted. Regarding long-term oncologic follow-up, the number of patients available for follow-up, time to follow-up, local and distant recurrence rate and overall as well as disease-free survival were collected.

RESULTS

The search strategy in MEDLINE yielded a total of 654 articles eligible for selection. Based on the in- and exclusion criteria, all articles were subsequently selected on title, abstract and full-text. Eventually, 18 studies were selected for inclusion in this review: 12 prospective[12,15-17,19-22,24-26,28], five retrospective cohort studies[13,14,18,23,29] and one prospective case-control study[27].

Most studies included colon as well as rectal cancer patients. Three studies only included colon cancer patients[23,25,29] and five only included rectal cancer patients[14,22,26,20,28]. Overall, a total number of 53329 patients were included in all individual studies. The median conversion rate was 14.3%. The median conversion rate for colon and rectal resections was 12.8% and 10.0%, respectively. Definition of conversion as well as description of surgeon’s experience in laparoscopic colorectal surgery was reported in 12 studies (66.7%)[12-17,19-21,23,24,26-28]. The baseline characteristics of the individual studies are reported in Table 1. Three studies reported significantly more male patients in the converted group (CG) compared to the laparoscopic group (LG)[14,16,29]. The body mass index (BMI) was significantly higher in the CG in five studies[14,18,20,27,28]. Neo-adjuvant chemo-radiation in rectal cancer patients was significantly more frequently applied in the CG in the study by Keller et al[22] (n = 63, 54.3% vs n = 19, 76.0%) and in the LG in the study by Rottoli et al[20] (n = 33, 22.4% vs n = 1, 3.8%). There were no significant differences between both groups in the other six studies reporting this item[13-16,19,26].

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of individual studies

| Ref. | Study design | Colon and/or rectal | No. patients |

Conversion (%) |

Men (%) |

Age (yr) |

BMI (kg/m2) |

|||||

| Overall | Colon resection | Rectal resection | LAP | CONV | LAP | CONV | LAP | CONV | ||||

| Allaix et al[13] | Retrospective | Both | 1114 | 122 (10.9) | 77 (10.7) | 45 (11.4) | 530 (53.4) | 69 (56.6) | 67.01 | 68.0 | 23.0 | 24.0 |

| Agha et al[14] | Retrospective | Rectal | 300 | 26 (8.6) | NA | 26 (8.6) | 166 (60.5)1 | 21 (80.7) | 64.7 | 64.5 | 26.21 | 29.0 |

| Biondi et al[12] | Prospective | Both | 207 | 33 (15.9) | 14 (42.4) | 19 (57.6) | 102 (58.6) | 23 (69.7) | 65.5 | 66.8 | NR | NR |

| Bouvet et al[15] | Prospective | Both | 91 | 38 (41.1) | NR | NR | 30 (56,6) | 25 (65.8) | 65.0 | 67.0 | NR | NR |

| Chan et al[16] | Prospective | Both | 470 | 41 (8.7) | NR (12.3) | NR (7.2) | 238 (55.5)1 | 30 (73.2) | 69.0 | 69.1 | NR | NR |

| Franko et al[21] | Prospective | Both | 174 | 31 (17.8) | NR | NR | 73 (51.0) | 21 (51.2) | 70.0 | 69.0 | NR | NR |

| Keller et al[22] | Prospective | Rectal | 141 | 25 (17.7) | NA | 25 (17.7) | 63 (54.3) | 17 (68.0) | 63.1 | 63.5 | 28.7 | 27.5 |

| Li et al[23] | Retrospective | Colon | 217 | 33 (15.2) | 33 (15.2) | NA | 94 (51.1) | 20 (60.7) | 62.6 | 62.9 | 25.6 | 24.5 |

| Martínek et al[17] | Prospective | Both | 243 | 17 (7.0) | 10 (6.3) | 7 (8.2) | 146 (64.6) | 13 (76.5) | 64.5 | 62.8 | 26.7 | 28.4 |

| Moloo et al[24] | Prospective | Both | 359 | 46 (12.8) | NR | NR | 171 (54.6) | 25 (54.3) | 65.0 | 65.0 | NR | NR |

| Ptok et al[25] | Prospective | Colon | 346 | 56 (16.2) | 56 (16.2) | NA | NR | NR | 66.5 | 68.9 | NR | NR |

| Rickert et al[26] | Prospective | Rectal | 162 | 38 (23.5) | NA | 38 (23.5) | 69 (55.7) | 27 (71.0) | 63.01 | 69.0 | 25.1 | 25.8 |

| Rottoli et al[20] | Prospective | Rectal | 173 | 26 (15.0) | NA | 26 (15.0) | NR | NR | 63.2 | 64.3 | 24.91 | 27.3 |

| Rottoli et al[27] | Prospective2 | Both | 93 | 31 (NA) | NR | NR | 37 (59.7) | 24 (77.4) | 72.0 | 72.0 | 26.81 | 29.6 |

| Scheidbach et al[18] | Retrospective | Both | 1409 | 80 (5.7) | 41 (8.2) | 39 (6.4) | 658 (49.5) | 46 (57.5) | 68.9 | 69.7 | 25.21 | 26.4 |

| White et al[19] | Prospective | Both | 175 | 25 (14.3) | NR | NR | 70 (46.7) | 11 (44.0) | 69.7 | 74.4 | 27.2 | 26.9 |

| Yamamoto et al[28] | Prospective | Rectal | 1073 | 78 (7.3) | NA | 78 (7.3) | 625 (62.8) | 48 (61.5) | 62.9 | 63.8 | 22.71 | 24.6 |

| Yerokun et al[29] | Retrospective | Colon | 46472 | 6144 (13.2) | 6144 (13.2) | NA | 19738 (48.9)1 | 3308 (53.8) | 70.01 | 69.0 | NR | NR |

P value of difference between overall LAP and CONV is < 0.05;

Case-control study. BMI: Body mass index; NR: Not reported; NA: Not applicable; LAP: Laparoscopic group; CONV: Converted group.

Type of colorectal resection

The type of colorectal resection performed in the individual patients was only reported in eight studies (44.4%). In all patients who underwent a colon resection in the LG, 362 (39.0%) had a right hemicolectomy, 271 (29.2%) a left hemicolectomy and 295 (31.8%) a sigmoid colon resection. The number of different colonic resections in the CG was 60 (42.6%), 40 (28.4%) and 41 (29.1%), respectively. In the rectal resection group, low anterior resection was performed in 1636 patients (82.6%) in the LG and 185 (80.4%) in the CG, abdominoperineal resection in 323 (16.3%) and 39 (17.0%), and Hartmann’s procedure in 22 (1.1%) and 6 (2.6%), respectively.

Reasons for conversion and intra-operative data

The reason for conversion was reported in 16 studies (88.9%) (Table 2). In more than half of them, tumor related aspects were the most frequent reason for conversion[12,13,18-20,23,24,25,27].

Table 2.

Reason for conversion, intra-operative blood loss and operative time

| Ref. |

Tumor related (%) |

Anatomic related (%) | Intra-operative complication (%) | Obesity (%) | Adhesions (%) | Other reason (%) |

Intra-operative blood loss (mL) |

Duration of operation (min) |

||||

| Overall | Colon | Rectal | ||||||||||

| LAP | CONV | LAP | CONV | |||||||||

| Allaix et al[13] | 59 (48.4) | 44 (57.1) | 15 (33.3) | 6 (4.9) | 5 (4.1) | 23 (18.8) | 18 (14.8) | 11 (9.0) | 1001 | 150 | 1401 | 180 |

| Agha et al[14] | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (19.2) | 10 (38.5) | 4 (15.4) | 7 (26.9) | NR | NR | 2151 | 258 |

| Biondi et al[12] | 17 (51.5) | NR | NR | 3 (9.1) | 6 (18.2) | 0 (0) | 6 (18.2) | 1 (3.0) | 96.41 | 184 | 162.01 | 187.9 |

| Bouvet et al[15] | 6 (15.8) | NR | NR | 10 (26.3) | 2 (5.3) | 0 (0) | 12 (31.6) | 8 (21.1) | NR | NR | 240 | 270 |

| Chan et al[16] | 11 (26.9) | NR | NR | 4 (9.8) | 6 (14.7) | 0 (0) | 14 (34.1) | 6 (14.7) | 191.21 | 461.9 | 179.4 | 187.2 |

| Franko et al[21] | 4 (12.9) | NR | NR | 18 (58.1) | 5 (16.1) | 0 (0) | NR | 4 (12.9) | NR | NR | 1601 | 182 |

| Keller et al[22] | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 741 | 253 | 242.61 | 260 |

| Li et al[23] | 15 (45.5) | 15 (45.5) | NA | 4 (12.1) | 4 (12.1) | 0 (0) | 10 (30.3) | 0 (0) | 901 | 147 | 1651 | 188 |

| Martínek et al[17] | 3 (17.6) | NR | NR | 6 (35.3) | 5 (29.4) | NR | NR | 3 (17.6) | 1771 | 415 | 1521 | 224 |

| Moloo et al[24] | 13 (28.3) | NR | NR | 12 (26.1) | 4 (8.7) | 0 (0) | 5 (10.9) | 11 (23.9) | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Ptok et al[25] | 15 (26.8) | 15 (26.8) | NA | 8 (14.3) | 7 (12.5) | 0 (0) | 9 (16.1) | 17 (30.4) | NR | NR | 178.9 | 186.7 |

| Rickert et al[26] | 7 (18.4) | NA | 7 (18.4) | 11 (28.9) | 4 (10.5) | 6 (15.8) | 6 (15.8) | 4 (10.5) | NR | NR | 345 | 363 |

| Rottoli et al[20] | 7 (26.9) | NA | 7 (26.9) | 10 (23.5) | 6 (23.1) | 0 (0) | 2 (7.7) | 1 (3.8) | NR | NR | 2851 | 342 |

| Rottoli et al[27] | 12 (38.7) | NR | NR | 6 (19.3) | 2 (6.5) | 0 (0) | 11 (35.5) | 0 (0) | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Scheidbach et al[18] | 24 (30.0) | NR | NR | 8 (10.0) | 14 (17.5) | 0 (0) | 15 (18.8) | 19 (23.7) | 2001 | 500 | 1801 | 232 |

| White et al[19] | 18 (72.0) | NR | NR | 0 (0) | 4 (12.0) | 0 (0) | 3 (12.0) | 0 (0) | NR | NR | 145.61 | 172 |

| Yamamoto et al[28] | 13 (16.7) | NA | 13 (16.7) | 26 (33.3) | 7 (9.0) | 12 (15.4) | 10 (12.8) | 10 (12.8) | 801 | 265 | 2701 | 295 |

| Yerokun et al[29] | NR | NR | NA | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

P value of difference between LAP and CONV is < 0.05. NR: Not reported; NA: Not applicable; LAP: Laparoscopic group; CONV: Converted group.

Intra-operative blood loss was reported in eight studies and ranged from 74 mL to 200 mL in the LG and from 147 mL to 500 mL in the CG. In all eight studies, intra-operative blood loss was significantly less in the LG compared to the CG (Table 2). Duration of surgery was significantly shorter in the LG in 11 of 15 studies reporting the operative time (Table 2).

Short-term postoperative outcomes

Several studies have compared the short-term outcomes of laparoscopic colorectal resections converted to open surgery to those achieved after laparoscopically completed colorectal resection, reporting controversial results. Postoperative complication rate ranged from 6.0% to 36.8% in the LG and from 15.4% to 61.2% in the CG (Table 3). In five studies (21.7%), postoperative complications occurred more frequently in the CG than in the LG[14,16,18,22,28], while 8 studies did not find any significant difference[12,13,15,17,20,25-27]. The wound infection rate was significantly lower in the LG in four out of ten studies reporting this topic[12,14,18,26]. A significant difference in anastomotic leakage rate was found in only one out of 11 studies, in favor of the LG (5.0% vs 13.8%)[18]. With regard to prolonged postoperative ileus, there was only one out of six studies reporting a significant difference in favor of the LG (1.1% vs 9.1%)[12]. Urologic and cardiopulmonary complications were reported in six studies (33.3%) and no significant differences were found between both groups[13,14,16,18,22,26,28]. Return to bowel function was only reported in four studies[12,13,18,23], and in two of them[18,23] bowel function returned significantly sooner in the LG (2.3 d vs 3.4 d and 3 d vs 4 d, respectively).

Table 3.

Postoperative data

| Ref. |

Postoperative complications (%) |

Wound

infection (%) |

Anastomotic

leakage (%) |

Mortality

(30-d) (%) |

Hospital

stay (d) |

|||||

| LAP | CONV | LAP | CONV | LAP | CONV | LAP | CONV | LAP | CONV | |

| Allaix et al[13] | 156 (15.7) | 20 (16.4) | 9 (0.9) | 3 (2.5) | 49 (4.9) | 4 (3.3) | 3 (0.3) | 1 (0.8) | 7 | 9 |

| Agha et al[14] | 101 (36.8)1 | 16 (61.2) | 33 (12.0)1 | 6 (23.0) | 23 (8.3) | 3 (11.5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 10 | 10.5 |

| Biondi et al[12] | 10 (6.0) | 11 (33.3) | 1 (0.6)1 | 2 (6.1) | 3 (1.7) | 1 (3.0) | NR | NR | 8.41 | 10.6 |

| Bouvet et al[15] | 13 (24.5) | 10 (26.3 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 1 (1.9) | 0 (0) | 61 | 8 |

| Chan et al[16] | 72 (16.7)1 | 23 (56.1) | 8 (1.9) | 6 (2.4) | 10 (2.3) | 1 (2.4) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (2.4) | 61 | 10 |

| Franko et al[21] | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 1 (0.7) | 2 (6.5) | 4.01 | 6.8 |

| Keller et al[22] | 25 (21.5)1 | 8 (32.0) | 2 (1.7) | 4 (20.0) | 3 (2.6) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0) | 4.41 | 6.8 |

| Li et al[23] | NR | NR | 4 (2.2) | 3 (9.1) | 14 (7.6) | 3 (9.1) | NR | NR | 41 | 8 |

| Martínek et al[17] | 65 (28.8) | 6 (35.3) | NR | NR | NR | NR | 7 (3.1) | 0 (0) | 11.3 | 12.5 |

| Moloo et al[24] | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Ptok et al[25] | 75 (25.9) | 22 (39.3) | NR | NR | NR | NR | 1 (0.3) | 1 (1.8) | NR | NR |

| Rickert et al[26] | 42 (33.9) | 19 (50.0) | 6 (4.8)1 | 7 (18.4) | 18 (16.4) | 7 (22.6) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.6) | 121 | 15 |

| Rottoli et al[20] | 34 (23.1) | 4 (15.4) | NR | NR | 17 (11.6) | 4 (15.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 8 | 9 |

| Rottoli et al[27] | 13 (21.0) | 7 (22.6) | NR | NR | 1 (1.6) | 1 (3.2) | 1 (1.6) | 0 (0) | NR | NR |

| Scheidbach et al[18] | 389 (28.5)1 | 41 (51.3) | 138 (10.4)1 | 16 (20.0) | 67 (5.0)1 | 11 (13.8) | 20 (1.5)1 | 4 (5.0) | NR | NR |

| White et al[19] | NR | NR | 14 (9.3) | 5 (20.0) | NR | NR | 0 (0) | 1 (4.0) | 8.31 | 14.4 |

| Yamamoto et al[28] | 210 (21.1)1 | 34 (43.6) | 56 (5.6) | 14 (17.9) | 72 (7.2) | 14 (17.9) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 141 | 20 |

| Yerokun et al[29] | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 419 (1.0)1 | 115 (1.9) | 51 | 6 |

P value of difference between LAP and CONV is < 0.05. NR: Not reported; LAP: Laparoscopic group; CONV: Converted group.

In four out of six studies, postoperative transfusion was necessary in significantly more patients in the CG[13,14,18,21], whereas no significant difference between both groups was found in the other two studies[20,27]. A previous pooled analysis of these data showed that converted patients were more likely to require postoperative blood transfusion than patients undergoing completed laparoscopic resection[30]. The 30-d mortality rate was not significantly different between both groups in most studies, although a significant difference in favor of the LG was found in three studies[18,21,29]. A previous meta-analysis of seven studies including 1655 patients showed that converted patients had a higher risk of 30-d mortality than patients with laparoscopically completed colorectal resection[30].

There was a range in reoperation rate in the LG from 4.9% to 17.7% and from 0% to 15.0% in the CG. Only one study reported a significant difference between both groups, in favor of LG (4.9% vs 15.0%)[18]. In 10 out of 14 studies, the hospital stay was significantly shorter in the LG[12,15,16,19,21-23,26,28,29], whilst no significant difference was present in the remaining studies[13,14,17,20]. The readmission rate was only reported in three studies[21,22,29]. A significant difference was found in one, in favor of the LG (5.0% vs 7.5%)[29]. The interpretation of these data is made difficult by several factors, including heterogeneous definitions of conversion, size and nature of the studies that in most cases did not separately analyze colon and rectal cancer patients.

Only a few studies assessed factors that might affect morbidity after conversion of laparoscopic colorectal resections. Aytac et al[31] performed a retrospective review of 2483 patients undergoing laparoscopic colorectal resection. A total of 270 were converted to open surgery. A high ASA score, previous abdominal surgery but not conversion were independently associated with postoperative complications. Among patients who required conversion to open surgery, smoking, cardiac co-morbidities, hypertension, previous abdominal surgery and intra-operative adhesions were factors significantly associated with increased postoperative complications. Patients who suffered postoperative complications had a significantly shorter time to conversion. However, it is worth to note that patients undergoing conversion within 50 min from the beginning of the operation were older and were more likely to have co-morbidities.

Conversion in colon cancer: When considering colon cancer patients, three large studies did not report significant differences in short-term outcomes[23,25,29]. Guillou et al[5] analyzed the short-term results of the Medical Research Council (MRC) CLASICC trial reporting similar rates of postoperative morbidity among 61 converted patients and 185 who had a completed laparoscopic colon resection (38% vs 34%). Our group[13] recently compared the early outcomes in 641 patients who had a completed laparoscopic colon resection and in 77 converted patients. No significant differences were observed in complication rate: 12.9% vs 14.5%, respectively (P = 0.864). Median length of hospital stay was 7 d vs 8 d, respectively (P = 0.303). Similar results were reported by Ptok et al[25] in a prospective study comparing 290 patients with completed laparoscopic colon resection and 56 converted patients: morbidity rate was 26% vs 39% and mortality rate was 1.8% vs 0.3%, respectively. Conversely, a retrospective review of the United States National Cancer Data Base including 40328 patients treated by completed laparoscopic colon resection and 6144 converted patients, found a slightly longer hospital stay (median 4 d vs 3 d) and higher rates of both readmission within 30 d (7.5% vs 5%) and mortality at 30 d (1.9% vs 1%) in the group of converted patients[29].

Conversion in rectal cancer: Only one RCT[5] and a few studies[14,22,28] focused on patients undergoing laparoscopic resection for rectal cancer, reporting worse short term outcomes in case of conversion to open surgery. The short-term results of the MRC CLASICC trial showed a higher 30-d postoperative complication rate in 82 converted patients compared to 160 patients who had a laparoscopic completed rectal resection: transfusion requirement, wound infections, pulmonary infection and anastomotic leakage rate were increased in converted patients[5]. Hospital stay was longer in these patients. Agha et al[14] analyzed rectal cancer patients undergoing elective laparoscopic rectal surgery. The overall complication rate was higher in the group of converted patients. Perioperative blood transfusions were needed in 11.5% of converted patients and in 1.9% of patients undergoing a completed laparoscopic rectal resection (P = 0.001). Wound infections occurred more frequently in converted patients (23% vs 12%, P = 0.01). Yamamoto et al[28] retrospectively reviewed 1073 patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery for rectal cancer. The postoperative morbidity rate was significantly higher after conversion: 43.6% vs 21.1%. The most common complications in converted patients were wound infection (17.9%), anastomotic leakage (17.9%) and small bowel obstruction (10.3%). The rate of these complications in the group of patients who had a completed laparoscopic rectal resection was 7.2% for anastomotic leakage, 5.6% for wound infection and 3.0% for small bowel obstruction. Resumption of gastrointestinal functions was significantly prolonged in the case of conversion and median length of hospital stay was significantly longer (20 d vs 14 d, P = 0.010). Similar results were observed by others[22].

Reactive vs pre-emptive conversion: The outcomes after a reactive or a pre-emptive conversion are poorly studied. Yang et al[32] matched 30 patients who had undergone a reactive conversion for several reasons including bleeding, bowel injury, ureter damage or splenic injury with 60 patients who had pre-emptive conversion and 60 patients who had a laparoscopically completed colorectal resection. After a reactive conversion, patients more frequently had a postoperative complication (50% vs 26.7%, P = 0.028), later resumption of a regular diet (6 d vs 5 d, P = 0.033) and a trend towards a longer hospital stay (8.1 d vs 7.1 d, P = 0.08) than patients who had a pre-emptive conversion. Aytac et al[31] found that reactive conversion was associated with a higher risk of postoperative pneumonia, bleeding and need for reoperation compared to patients requiring pre-emptive conversion to open surgery. Overall morbidity, length of hospital stay and readmission rates were slightly worse in patients with reactive conversion, even though the differences did not reach statistical significance.

The increased rate of postoperative morbidity after reactive conversion might be related to the sequelae of the intraoperative complication that leads to a reactive conversion, suggesting that a low threshold for conversion is advisable in challenging cases, thus avoiding a dangerous and lengthy dissection. However, the best timing of conversion is unclear. Belizon et al[33] found that the postoperative morbidity rate significantly decreased if the decision to convert was taken within or after the first 30 min of the procedure (40% vs 86.9%, P < 0.05). Conversely, Aytac et al[31] reported that timing of conversion did not adversely affect the postoperative outcomes: 72 patients converted within the first 30 min had similar overall morbidity, reoperation and readmission rates as 198 patients who had late conversion. However, the interpretation of these findings is biased by the fact that several patients in both groups underwent reactive conversion. Further studies are needed to better clarify the real impact of conversion timing on the postoperative course.

Converted vs open colorectal resection: While several studies have compared the short-term outcomes after conversion in laparoscopic colorectal resection to those observed after laparoscopically completed colorectal resection, there are limited data on the effects of conversion compared to planned open surgery. The evidence is controversial with some studies showing a worse postoperative course in converted patients and others reporting no significant differences[34]. In particular, among 4 studies that included only rectal cancer patients, one found better results in converted patients[35], one reported better outcomes after planned open rectal resection[36] and two found no differences[26,37]. Recently, Giglio et al[34] conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of short term outcomes after laparoscopic converted or open colorectal resection. The aim was to determine if conversion is a drawback or a complication of laparoscopic colorectal resection burdened by additional postoperative morbidity. The authors identified 20 studies including a total of 30656 patients undergoing open surgery and 11085 having laparoscopic colorectal resection. A total of 1935 patients (17%) in the laparoscopic group were converted to open surgery. Colorectal cancer was the indication for surgery in 13 of the studies included in this meta-analysis, while both benign and malignant diseases were included in seven. A total of five studies only included rectal cancer patients, while other five only analyzed colon resections. The risk of bias was moderate to high in 11 studies. No differences in 30-d mortality and 30-d morbidity rates were found. While a higher rate of wound infection was observed among converted patients, no significant differences were observed between both groups in length of hospital stay, anastomotic leakage, postoperative bleeding, sepsis, cardiac complications, deep venous thrombosis and reoperation rates. Subgroup analyses on mortality, overall morbidity and length of hospital stay according to the site of disease (colon vs rectum), and indication for surgery (cancer vs benign disease) showed that the short-term outcomes in converted patients were comparable to those observed in patients treated by open surgery. The learning curve of the surgeon and the reason for conversion did not show any adverse impact on the postoperative course of converted patients.

Very recently, Masoomi et al[38] published the results of a retrospective analysis of 646414 patients from the United States National Inpatient Sample undergoing laparoscopic (27.7%) or open colorectal resection for both benign and malignant diseases. The conversion rate of laparoscopic to open surgery was 16.6%. They found that the group of converted patients had significantly better outcomes compared to the open group, with a lower in-hospital mortality rate. Even though the length of hospital stay was similar between the two groups, the median total hospital charge was $2800 higher in the converted group compared to the open group. Similar results were reported by Yerokun et al[29] who used the United States National Cancer Data Base to identify patients undergoing elective colon resection for stage I-III colon cancer between 2010 and 2012. Of 104400 patients, 40328 (38.6%) underwent laparoscopic colectomy, 57928 (55.5%) open colectomy and 6144 (5.9%) converted colectomy. After adjustment for patient, clinical and treatment characteristics, conversion to open surgery was associated with a significantly reduced 30-d mortality (1.9% vs 2.8%, P < 0.001), a shorter hospital stay and a reduced 30-d readmission rate (5.9% vs 7.5%, P < 0.001) when compared to open surgery.

Since converted colon resection is still associated with better outcomes than planned open colon resection, the authors concluded that the laparoscopic approach in patients with colon cancer should be attempted in all cases with no contraindications to laparoscopy. Even though there is increasing evidence showing that conversion of laparoscopic colon resection does not impair short-term outcomes, the data are not definitive and robust data regarding conversion of laparoscopic rectal resection are missing. While waiting further studies to confirm these results and to shed more light on the impact of conversion of laparoscopic rectal resections, several studies have been conducted aiming to identify risk factors for conversion. Algorithms to predict conversion from laparoscopic colorectal resection to open surgery have been proposed; however, most of them are not specific for colorectal cancer[39-41]. To date, only a few studies have been focused on predictors of conversion in patients with colon or rectal cancer. Thorpe et al[42] analyzed the data from the MRC Conventional vs Laparoscopic-Assisted Surgery in Colorectal Cancer (CLASICC). They found that locally advanced tumor, BMI, and ASA score greater than 3 were independent risk factors for conversion in colon cancer patients. Similarly, BMI and male sex were independently associated with conversion in rectal cancer patients. BMI was also identified as risk factor for conversion in rectal cancer patients by Yamamoto et al[28] in a retrospective analysis of 1073 rectal cancer patients.

A model to predict conversion to open surgery during laparoscopic rectal resection for cancer was proposed by Zhang et al[43]. Six possible risk factors for conversion were extracted from a review of the literature and a series of 602 laparoscopic rectal resections, including male sex, surgical experience (at least 25 previous laparoscopic rectal resections), previous open abdominal surgery, BMI ≥ 28, tumor diameter ≥ 6 cm, and tumor invasion, for which a score of relevance was assigned. Further studies however are needed to confirm this model.

Histological outcome of the colorectal specimen

The tumor (T) stage was reported in 10 studies (55.6%)[12-17,19,23,25,27]. In most of them (n = 7), no significant differences in T-stage were found between both groups. In the study by Allaix et al[13], T1 was significantly more frequent in the LG (n = 345, 34.8% vs n = 9, 7.4%), whilst T3 and T4 were significantly more frequent in the CG (n = 446, 45.0% vs n = 85, 69.7% for T3, and n = 37, 3.7% vs n = 15, 12.3% for T4, respectively). Agha et al[14] found significantly more T2-tumors in the LG (n = 87, 31.7% vs n = 5, 19.2%) and significantly more T4-tumors in the CG (n = 10, 3.6% vs n = 6, 23.0%). In the study by Bouvet et al[15], T4-tumors were significantly more frequent in the CG (n = 1, 1.9% vs n = 5, 13.2%), whilst the other T-stages were comparable between both groups in this study.

The number of lymph nodes harvested was similar between both groups in all 13 studies reporting this item[12,13,15-17,20-23,26-29]. The number of harvested lymph nodes ranged from 8 to 20.2 in the LG and from 9 to 22.4 in the CG. The N-stage was reported in five studies (27.8%)[12,13,20,25,26]; in two of these studies[12,13], the N0-stage was significantly more frequent in the LG (n = 679, 68.4% vs n = 67, 54.9% and n = 92, 52.9% vs n = 8, 24.2%, respectively).

The tumor size ranged from 3.5 to 5.1 cm in the LG and from 3.5 to 5.6 cm in the CG. In three out of seven studies (42.9%), the tumor size was significantly larger in the CG (5.3 cm vs 3.9 cm, 5.0 cm vs 4.0 cm and 4.0 cm vs 3.7 cm, respectively)[12,16,29]. Tumor margin status was also reported in seven studies[13,14,17,20,26,27,29] and in one of these, tumor margin positivity was significantly more frequent in the CG (n = 319, 5.2% vs n = 1075, 2.7%)[29].

Disease stage was reported in all studies, although incomplete in two[20,18]. In seven studies, stage I-III patients were included[12,13,19,21,23,25,29], in three stage I-IV[14,17,24], in four studies stage 0-IV[15,16,22,28] and in two studies stage 0-III[26,27]. In three studies[12,13,29], disease stage I was significantly more frequent in the LG, whilst stage III was more frequent in the CG. In the studies by Biondi et al[12] and Yerokun et al[29], stage II was also significantly more frequent in the LG. In the studies by Agha et al[14] and Rottoli et al[20], stage IV disease was significantly more frequent in the CG as well.

Long-term oncologic outcome

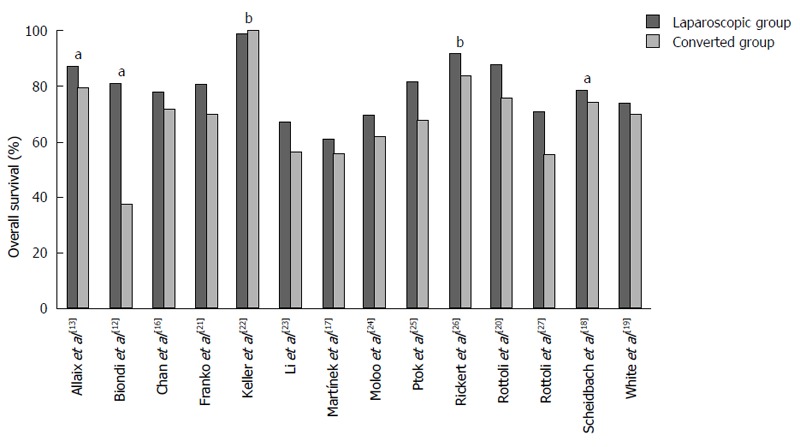

Survival: Most of the studies reported one or more long-term oncologic outcome measures. Overall survival (OS) was reported in fourteen studies[12,13,16-27] (Figure 1). The median 5-year OS was 79.7% (61.0%-99.1%) in the LG and 70.2% (38.0%-100%) in the CG. OS was in favor of the patients in the LG in all studies, except in the study by Keller et al[22], who reported an extremely high OS in both groups. However, there was a statistically significant difference in OS in only three studies in favor of the LG[12,13,18]. The lack of significance in OS between LG and CG in the other series might be caused by the small number of patients included, as two of the studies reporting a significant difference in OS were very large studies including more than one thousand patients[13,18]. Additionally, the interpretation of the outcome with regard to OS is also complicated by the fact that in most studies colon as well as rectal cancer patients were included. OS was reported in three of the five studies only including rectal cancer patients[20,22,26] and in two of the three studies in which only colon cancer patients were included[23,25]. In none of these studies, there was a significant difference in OS found between the laparoscopic and converted group.

Figure 1.

Overall survival rates reported in the individual studies. aP value of difference between the laparoscopic and converted group is < 0.05; b3-yr overall survival rates, the other studies reported 5-yr overall survival rates.

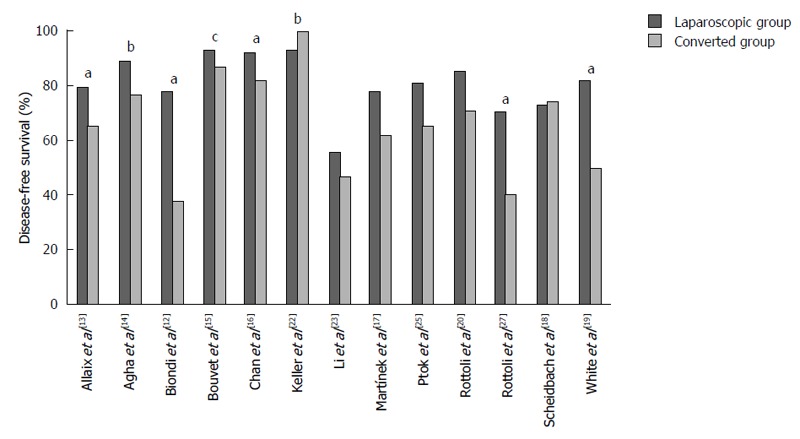

The 5-year disease-free survival (DFS) was reported in ten studies[12,13,16-20,23,25,27], whilst 3 and 2-year DFS was reported in two[14,22] and one study[15], respectively (Figure 2). The median DFS was 81.3% (55.5%-93.1%) in the LG and 65.6% (38.0%-100%) in the CG. DFS was in favor of the LG in all, except two studies[18,22]. A statistical significant difference was found in five of the studies reporting a favorable outcome in the LG (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Disease-free survival rates reported in the individual studies. aP value of difference between the laparoscopic and converted group is < 0.05; b3-yr and c2-yr disease-free survival rates, the other studies reported 5-yr disease-free survival rates.

The significant worse OS and DFS in the CG might be related to several factors other than conversion itself, including a locally advanced tumor[30]. We performed a multivariate analysis of predictors of survival in our study and found pT4 tumor stage and a positive lymph node ratio ≥ 0.25, but not conversion itself as independent predictors of poor OS and DFS[13]. In addition, an adverse survival in converted patients might be explained by a more extensive inflammatory response due to more tissue damage as well as a higher postoperative complication rate compared to the laparoscopic group of patients[30].

Recurrence: The local and distant recurrence rate was also reported in some studies. Median duration of follow-up in the studies reporting these recurrence rates was 35 (22.5-120) mo in the LG and 34.1 (23.6-120) mo in the CG. At follow-up, local recurrence rate ranged from 2.6% to 15.8% in the LG and from 0% to 26.3% in the CG. A statistically significant difference in local recurrence rate between both groups was only found in one of the studies: Chan et al[16] reported a significant difference in local recurrence rate of 2.8% in the LG and 9.8% in the CG after 31 mo of follow-up (P < 0.001). Four studies reported the local recurrence rate in a study population of only rectal cancer patients. In three of these studies, the local recurrence rate was comparable: 3% in both groups after 34 months of follow-up in the study by Rickert et al[26], 4.8% in the LG and 3.8% in the CG (P = 0.875) after almost two years of follow-up in the study by Agha et al[14]; in the study by Keller et al[22] local recurrence was only present in the LG, in 2.6% of patients after 38.2 mo of follow-up (P = 0.07). Rottoli et al[20] reported a large difference in local recurrence rate between both groups; 11.4% in the LG and 26.3% in the CG, although this did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.07). However, this large difference in recurrence rate between both groups might be explained by the difference in duration of follow-up of 10 mo between both groups in this study; 36 months in the LG and 46 months in the CG.

The rate of distant metastases in the LG en CG was reported in seven studies[13,14,17,22,23,26,27], ranging from 4.3% to 17.3% in the LG and from 0% to 22.6% in the CG. In three of these seven studies[13,14,27], the distant metastasis rate was noteworthy higher in the CG, even though the difference did not reach the statistical significance. In two of these studies both colon and rectal cancer patients were included: Rottoli et al[27] reported a distant metastasis rate of 9.9% in the LG and 21.8% in the CG after a follow-up of approximately four years (P = 0.79), and in the study by our group[13] the distant metastasis rate was 16.1% in the LG and 22.6% in the CG after ten years of follow-up (P = 0.244). Agha et al[14] only included rectal cancer patients and reported a distant recurrence rate of 13.1% in the LG and 19.2% in the CG (P = 0.390). The distant metastasis rate was comparable between both groups in the other four studies.

CONCLUSION

This review of the literature has demonstrated that conversion of laparoscopic colon resection does not seem to significantly increase the postoperative morbidity, while the results after converted laparoscopic resection for rectal cancer are less favorable than those achieved by patients who had a completely laparoscopic surgery. With regard to long-term oncologic outcome, OS and DFS in the case of conversion in laparoscopic colorectal cancer surgery seems to be worse compared to the group of patients in whom resection was successfully completed by laparoscopy. However, it remains difficult to draw a proper conclusion due to the heterogeneity of the long-term oncologic outcomes as well as the inclusion of both colon and rectal cancer patients in most of the studies. Poorer survival in converted patients seems to be multifactorial, including tumor stage as well as inflammatory response secondary to more tissue damage and sequelae of postoperative complications.

Footnotes

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Italy

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Conflict-of-interest statement: No conflict of interest.

Peer-review started: April 29, 2016

First decision: June 20, 2016

Article in press: August 5, 2016

P- Reviewer: Giglio MV, Lakatos PL, Wasserberg N S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

References

- 1.Jacobs M, Verdeja JC, Goldstein HS. Minimally invasive colon resection (laparoscopic colectomy) Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1991;1:144–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kwon S, Billingham R, Farrokhi E, Florence M, Herzig D, Horvath K, Rogers T, Steele S, Symons R, Thirlby R, et al. Adoption of laparoscopy for elective colorectal resection: a report from the Surgical Care and Outcomes Assessment Program. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;214:909–918.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Veldkamp R, Kuhry E, Hop WC, Jeekel J, Kazemier G, Bonjer HJ, Haglind E, Påhlman L, Cuesta MA, Msika S, et al. Laparoscopic surgery versus open surgery for colon cancer: short-term outcomes of a randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6:477–484. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70221-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van der Pas MH, Haglind E, Cuesta MA, Fürst A, Lacy AM, Hop WC, Bonjer HJ. Laparoscopic versus open surgery for rectal cancer (COLOR II): short-term outcomes of a randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:210–218. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guillou PJ, Quirke P, Thorpe H, Walker J, Jayne DG, Smith AM, Heath RM, Brown JM. Short-term endpoints of conventional versus laparoscopic-assisted surgery in patients with colorectal cancer (MRC CLASICC trial): multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;365:1718–1726. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66545-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buunen M, Veldkamp R, Hop WC, Kuhry E, Jeekel J, Haglind E, Påhlman L, Cuesta MA, Msika S, Morino M, et al. Survival after laparoscopic surgery versus open surgery for colon cancer: long-term outcome of a randomised clinical trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:44–52. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70310-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonjer HJ, Deijen CL, Abis GA, Cuesta MA, van der Pas MH, de Lange-de Klerk ES, Lacy AM, Bemelman WA, Andersson J, Angenete E, et al. A randomized trial of laparoscopic versus open surgery for rectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1324–1332. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jayne DG, Thorpe HC, Copeland J, Quirke P, Brown JM, Guillou PJ. Five-year follow-up of the Medical Research Council CLASICC trial of laparoscopically assisted versus open surgery for colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2010;97:1638–1645. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Green BL, Marshall HC, Collinson F, Quirke P, Guillou P, Jayne DG, Brown JM. Long-term follow-up of the Medical Research Council CLASICC trial of conventional versus laparoscopically assisted resection in colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2013;100:75–82. doi: 10.1002/bjs.8945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fleshman J, Sargent DJ, Green E, Anvari M, Stryker SJ, Beart RW, Hellinger M, Flanagan R, Peters W, Nelson H. Laparoscopic colectomy for cancer is not inferior to open surgery based on 5-year data from the COST Study Group trial. Ann Surg. 2007;246:655–662; discussion 662-664. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318155a762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuhry E, Schwenk W, Gaupset R, Romild U, Bonjer J. Long-term outcome of laparoscopic surgery for colorectal cancer: a cochrane systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Cancer Treat Rev. 2008;34:498–504. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Biondi A, Grosso G, Mistretta A, Marventano S, Tropea A, Gruttadauria S, Basile F. Predictors of conversion in laparoscopic-assisted colectomy for colorectal cancer and clinical outcomes. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2014;24:e21–e26. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e31828f6bc0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allaix ME, Degiuli M, Arezzo A, Arolfo S, Morino M. Does conversion affect short-term and oncologic outcomes after laparoscopy for colorectal cancer? Surg Endosc. 2013;27:4596–4607. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-3072-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agha A, Fürst A, Iesalnieks I, Fichtner-Feigl S, Ghali N, Krenz D, Anthuber M, Jauch KW, Piso P, Schlitt HJ. Conversion rate in 300 laparoscopic rectal resections and its influence on morbidity and oncological outcome. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008;23:409–417. doi: 10.1007/s00384-007-0425-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bouvet M, Mansfield PF, Skibber JM, Curley SA, Ellis LM, Giacco GG, Madary AR, Ota DM, Feig BW. Clinical, pathologic, and economic parameters of laparoscopic colon resection for cancer. Am J Surg. 1998;176:554–558. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(98)00261-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chan AC, Poon JT, Fan JK, Lo SH, Law WL. Impact of conversion on the long-term outcome in laparoscopic resection of colorectal cancer. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:2625–2630. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-9813-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martínek L, Dostalík J, Guňková P, Guňka I, Vávra P, Zonča P. Impact of conversion on outcome in laparoscopic colorectal cancer surgery. Wideochir Inne Tech Maloinwazyjne. 2012;7:74–81. doi: 10.5114/wiitm.2011.25799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scheidbach H, Garlipp B, Oberländer H, Adolf D, Köckerling F, Lippert H. Conversion in laparoscopic colorectal cancer surgery: impact on short- and long-term outcome. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2011;21:923–927. doi: 10.1089/lap.2011.0298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.White I, Greenberg R, Itah R, Inbar R, Schneebaum S, Avital S. Impact of conversion on short and long-term outcome in laparoscopic resection of curable colorectal cancer. JSLS. 2011;15:182–187. doi: 10.4293/108680811X13071180406439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rottoli M, Bona S, Rosati R, Elmore U, Bianchi PP, Spinelli A, Bartolucci C, Montorsi M. Laparoscopic rectal resection for cancer: effects of conversion on short-term outcome and survival. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:1279–1286. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0398-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Franko J, Fassler SA, Rezvani M, O’Connell BG, Harper SG, Nejman JH, Zebley DM. Conversion of laparoscopic colon resection does not affect survival in colon cancer. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:2631–2634. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-9812-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keller DS, Khorgami Z, Swendseid B, Champagne BJ, Reynolds HL, Stein SL, Delaney CP. Laparoscopic and converted approaches to rectal cancer resection have superior long-term outcomes: a comparative study by operative approach. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:1940–1948. doi: 10.1007/s00464-014-3419-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li J, Guo H, Guan XD, Cai CN, Yang LK, Li YC, Zhu YH, Li PP, Liu XL, Yang DJ. The impact of laparoscopic converted to open colectomy on short-term and oncologic outcomes for colon cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19:335–343. doi: 10.1007/s11605-014-2685-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moloo H, Mamazza J, Poulin EC, Burpee SE, Bendavid Y, Klein L, Gregoire R, Schlachta CM. Laparoscopic resections for colorectal cancer: does conversion survival? Surg Endosc. 2004;18:732–735. doi: 10.1007/s00464-003-8923-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ptok H, Kube R, Schmidt U, Köckerling F, Gastinger I, Lippert H. Conversion from laparoscopic to open colonic cancer resection - associated factors and their influence on long-term oncological outcome. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2009;35:1273–1279. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rickert A, Herrle F, Doyon F, Post S, Kienle P. Influence of conversion on the perioperative and oncologic outcomes of laparoscopic resection for rectal cancer compared with primarily open resection. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:4675–4683. doi: 10.1007/s00464-013-3108-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rottoli M, Stocchi L, Geisler DP, Kiran RP. Laparoscopic colorectal resection for cancer: effects of conversion on long-term oncologic outcomes. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:1971–1976. doi: 10.1007/s00464-011-2137-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamamoto S, Fukunaga M, Miyajima N, Okuda J, Konishi F, Watanabe M. Impact of conversion on surgical outcomes after laparoscopic operation for rectal carcinoma: a retrospective study of 1,073 patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;208:383–389. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yerokun BA, Adam MA, Sun Z, Kim J, Sprinkle S, Migaly J, Mantyh CR. Does Conversion in Laparoscopic Colectomy Portend an Inferior Oncologic Outcome? Results from 104,400 Patients. J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;20:1042–1048. doi: 10.1007/s11605-016-3073-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clancy C, O’Leary DP, Burke JP, Redmond HP, Coffey JC, Kerin MJ, Myers E. A meta-analysis to determine the oncological implications of conversion in laparoscopic colorectal cancer surgery. Colorectal Dis. 2015;17:482–490. doi: 10.1111/codi.12875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aytac E, Stocchi L, Ozdemir Y, Kiran RP. Factors affecting morbidity after conversion of laparoscopic colorectal resections. Br J Surg. 2013;100:1641–1648. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang C, Wexner SD, Safar B, Jobanputra S, Jin H, Li VK, Nogueras JJ, Weiss EG, Sands DR. Conversion in laparoscopic surgery: does intraoperative complication influence outcome? Surg Endosc. 2009;23:2454–2458. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0414-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Belizon A, Sardinha CT, Sher ME. Converted laparoscopic colectomy: what are the consequences? Surg Endosc. 2006;20:947–951. doi: 10.1007/s00464-005-0553-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Giglio MC, Celentano V, Tarquini R, Luglio G, De Palma GD, Bucci L. Conversion during laparoscopic colorectal resections: a complication or a drawback? A systematic review and meta-analysis of short-term outcomes. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2015;30:1445–1455. doi: 10.1007/s00384-015-2324-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laurent C, Leblanc F, Wütrich P, Scheffler M, Rullier E. Laparoscopic versus open surgery for rectal cancer: long-term oncologic results. Ann Surg. 2009;250:54–61. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181ad6511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mroczkowski P, Hac S, Smith B, Schmidt U, Lippert H, Kube R. Laparoscopy in the surgical treatment of rectal cancer in Germany 2000-2009. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:1473–1478. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2012.03058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Penninckx F, Kartheuser A, Van de Stadt J, Pattyn P, Mansvelt B, Bertrand C, Van Eycken E, Jegou D, Fieuws S. Outcome following laparoscopic and open total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2013;100:1368–1375. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Masoomi H, Moghadamyeghaneh Z, Mills S, Carmichael JC, Pigazzi A, Stamos MJ. Risk factors for conversion of laparoscopic colorectal surgery to open surgery: does conversion worsen outcome? World J Surg. 2015;39:1240–1247. doi: 10.1007/s00268-015-2958-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tekkis PP, Senagore AJ, Delaney CP. Conversion rates in laparoscopic colorectal surgery: a predictive model with, 1253 patients. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:47–54. doi: 10.1007/s00464-004-8904-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cima RR, Hassan I, Poola VP, Larson DW, Dozois EJ, Larson DR, O’Byrne MM, Huebner M. Failure of institutionally derived predictive models of conversion in laparoscopic colorectal surgery to predict conversion outcomes in an independent data set of 998 laparoscopic colorectal procedures. Ann Surg. 2010;251:652–658. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181d355f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schlachta CM, Mamazza J, Seshadri PA, Cadeddu MO, Poulin EC. Predicting conversion to open surgery in laparoscopic colorectal resections. A simple clinical model. Surg Endosc. 2000;14:1114–1117. doi: 10.1007/s004640000309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thorpe H, Jayne DG, Guillou PJ, Quirke P, Copeland J, Brown JM. Patient factors influencing conversion from laparoscopically assisted to open surgery for colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2008;95:199–205. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang GD, Zhi XT, Zhang JL, Bu GB, Ma G, Wang KL. Preoperative prediction of conversion from laparoscopic rectal resection to open surgery: a clinical study of conversion scoring of laparoscopic rectal resection to open surgery. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2015;30:1209–1216. doi: 10.1007/s00384-015-2275-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]