Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the long-term efficacy of ciliary neurotrophic factor delivered via an intraocular encapsulated cell implant for the treatment of retinitis pigmentosa (RP).

Design

Long-term follow up of a multicenter, sham-controlled study.

Methods

Thirty-six patients at three CNTF4 sites were randomly assigned to receive a high- or low- dose implant in one eye and sham surgery in the fellow eye. The primary endpoint (change in visual field sensitivity at 12 months) has been reported previously.1 Here we report long-term visual acuity, visual field and optical coherence tomography (OCT) outcomes in 24 patients either retaining or explanting the device at 24 months relative to sham-treated eyes.

Results

Eyes retaining the implant showed significantly greater visual field loss from baseline than either explanted eyes or sham eyes through 42 months. By 60 months and continuing through 96 months, visual field loss was comparable among sham-treated eyes, eyes retaining the implant and explanted eyes, as was visual acuity and OCT macular volume.

Conclusions

Over the short term, ciliary neurotrophic factor released continuously from an intra-vitreal implant lead to loss of total visual field sensitivity that was greater than the natural progression in the sham-treated eye. This additional loss of sensitivity related to the active implant was reversible when the implant was removed. Over the long term (60 – 96 months), there was no evidence of efficacy for visual acuity, visual field sensitivity or OCT measures of retinal structure.

A major challenge in the treatment of retinitis pigmentosa (RP) is the safe and effective delivery of therapeutic macromolecules to the retina. One potential approach to this challenge is an intraocular encapsulated-cell implant to enable controlled, continuous, and long-term delivery of therapeutic macromolecules, including neurotrophic factors.1,2 Ciliary neurotrophic factor is a member of the interleukin-6 (IL-6) family of cytokines and interacts with a tripartite receptor complex composed of ciliary neurotrophic factor receptor α plus two signal-transducing transmembrane units, leukemia inhibitory factor receptor β and glycoprotein 130 (gp130).3 Ciliary neurotrophic factor receptor α is located on Müller glial membranes4 and on rod and cone photoreceptors5. Ciliary neurotrophic factor has been shown to rescue photoreceptors after a single intraocular injection in a variety of animal models of RP 6–11 and with maintained exposure through gene therapy in mouse models12–14. However, retinal degeneration models treated with ciliary neurotrophic factor may also show suppression of retinal function as measured with the electroretinogram, suggesting that dosage and duration of exposure can be critical 13,14.

A therapeutic approach to treatment with ciliary neurotrophic factor in patients with RP was established through sustained-release delivery with intraocular encapsulated cell technology implants (NT-501; Neurotech USA, Cumberland, Rhode Island, USA). After showing safety and efficacy in animal models 11, the ciliary neurotrophic factor implants passed appropriate milestones in a phase 1 human clinical study of RP 2. Thus, two Phase 2 studies (CNTF3 and CNTF4) were designed to evaluate the effect of ciliary neurotrophic factor on retinal structure and function in patients with RP. CNTF3 was motivated by preliminary evidence of visual acuity improvement in the Phase 1 trial. The primary endpoint was change in best-corrected acuity at 12 months. As reported previously 1, no significant changes in visual acuity were observed in ciliary neurotrophic factor or sham-treated eyes, effectively ruling out any short-term benefit to visual acuity from the ciliary neurotrophic factor implants.

CNTF4 sought to determine whether sustained-release of ciliary neurotrophic factor could slow the progression of visual field loss in patients with RP and visual acuity of 20/63 or better.1 Patients (n=68) were randomized to either high- or low-dose NT-501 implants in 2:1 ratio in 1 eye, and a sham treatment in the fellow eye. The high dose was selected based on the dose-response effect of ciliary neurotrophic factor in the rcd1 dog model of retinal degeneration and was the maximum effective dose. The low dose was 50% of the minimum effective dose in the dog model. The primary outcome at 12 months was the change in total visual field sensitivity, as determined by the sum of the thresholds for the 76 locations with the Humphrey visual field 30-2 test. As reported previously1, eyes treated with the high-dose implant showed a greater loss of total visual field sensitivity compared to sham, and this decrease was reversible with implant removal. Ciliary neurotrophic factor also resulted in a dose-dependent increase in retinal thickness. Ancillary studies with Adaptive Optics Scanning Laser Ophthalmoscopy showed cone preservation in ciliary neurotrophic factor-treated eyes compared with the sham-treated fellow eyes in a subset of CTNF4 participants 15,16.

CNTF3 and CNTF4 showed that long-term intraocular delivery of ciliary neurotrophic factor could be safely achieved through intraocular implants.1 They also demonstrated that there was no demonstrable benefit to the patients at 12 months. However, ciliary neurotrophic factor showed clear biological activity as indicated by the dose-dependent increase in macular thickness and a decrease in visual field sensitivity in the treated eye. These studies did not address, however, long-term consequences of intraocular ciliary neurotrophic factor. Ciliary neurotrophic factor down-regulates phototransduction and reduces ERG amplitude9,17,18, consistent with reduced visual field sensitivity at 12 months. What is not known, however, is whether this down-regulation over the short-term is associated with preservation of photoreceptors over the long term as in mouse models of RP.13,14 The goal of the present study, therefore, was to determine the functional and structural status of patients many years after the ciliary neurotrophic factor treatment.

Methods

Patients were followed for 24 months in the CNTF4 trial (registered as NCT00447980 on clinicaltrials.gov). There was an optional registry study in which the patients were followed for an additional 12 months. Three of the CNTF4 study sites continued to follow 24 patients out of the 36 enrolled for durations up to 8 years (mean duration of follow-up = 80 months). These included 8 patients with the low-dose device and 16 patients with the high-dose device. The original trial design approved by the FDA specified that implants be removed at 24 months. After the initiation of the trial, the FDA recommended that patients retain the implants at the end of the study (avoiding a second surgery). Since all patients had consented to have their implants removed at the end of the study, they were informed of study results to date, given an updated risk/benefit assessment, and offered a choice either to keep the implant in place (n=14) or to have the implant removed (n=10). Institutional Review Boards for each participating site approved the study and subjects signed written informed consent forms prior to participation in the study.

BCVA was measured by an electronic visual acuity tester (EVA) using the ETDRS protocol.19 Visual field sensitivity was measured with the 30-2 grid using the Humphrey visual field analyzer. Visual field sensitivity was measured twice per eye on each of 3 baseline visits. Eligibility for enrollment was determined by the results of baseline 1. The average value of the two baseline 2 and two baseline 3 examinations (4 total), each representing the sum of actual thresholds for all 76 locations, provided the baseline visual field sensitivity. During the CNTF4 trial, four visual field sensitivity measurements per eye were taken for each subsequent visit and the average of the four visual field sensitivity sums was used to assess the change from baseline. On follow-up visits beyond 30 months, visual fields were typically obtained without replicates. Retinal thickness and morphology were evaluated by OCT. During the CNTF4 trial, the fast macular thickness map protocol, a 7-mm horizontal line scan, and 6-mm vertical line scan was obtained with the Stratus OCT (Carl Zeiss Meditec, Inc, Dublin, California, USA). On follow-up visits beyond 30 months, spectral domain (SD)-OCTs were obtained with the Heidelberg Spectralis HRA+OCT (Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany).

Results

A summary of outcome data on the visit approximately 80 months post implant surgery is shown in Table 1. Mean logMAR BCVA in the ciliary neurotrophic factor treated eye at follow-up was 0.26 (20/32). This was not significantly different (P = 0.96) than the mean logMAR BCVA in the sham eye of 0.25 (20/32).

Table 1.

Outcome data at 80 months post implant. Values are for the eye receiving encapsulated cell intraocular implant releasing ciliary neurotrophic factor and the sham eye in patients with retinitis pigmentosa.

| Implant | Sham | diff (95% CI, significance) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Best-corrected visual acuity (logMAR) | Mean (SD) | 0.26 (SD: 0.23) | 0.25 (SD: 0.32) | 0.004 (-0.16 to 0.15, P = 0.96) |

| Change in visual field sensitivity (dB) | Mean (SD) | -468 (SD: 252) | -475 (SD: 229) | 7.0 (-33 to 70, P = 0.40) |

| Total macular volume (mm3) | Mean (SD) | 7.23 (SD: 0.87) | 7.15 (SD: 0.88) | 0.08 (-0.12 to 0.29, P = 0.41) |

Changes in total visual field sensitivity on the final visit were comparable (P = 0.88) for those receiving the low dose device and those receiving the high dose device, so doses were combined for subsequent analyses. On the final visit at an average of 80 months post implantation, the total sensitivity loss in explanted eyes (-378 dB) was not significantly different (P = 0.29) from the total loss in eyes retaining the device (-492 dB). Combining low and high dose eyes, and explant versus no explant, the average difference from baseline on the final visit for treated eyes (-468 dB) was 7.0 dB less (95% CI = -33 to 30, P=0.40) than for sham eyes (-475 dB).

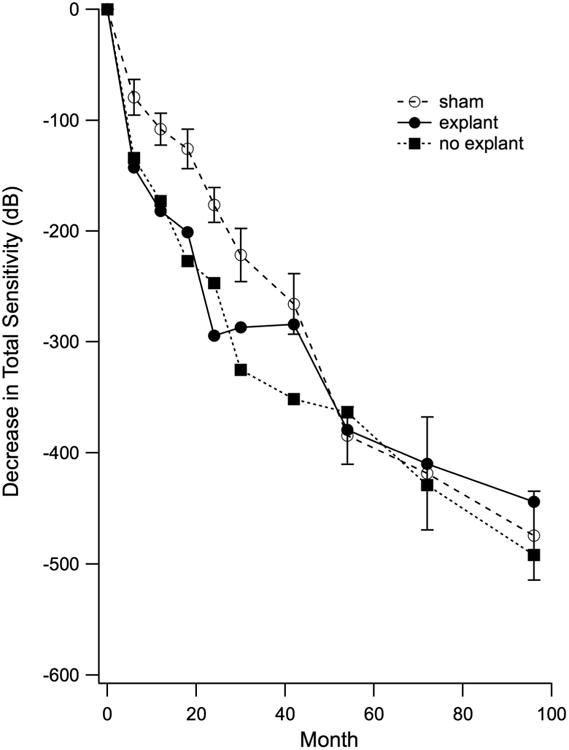

Changes from baseline in total visual field sensitivity are shown for each visit in Figure 1. All patients (n=24) were followed to 30 months. For extended follow-up, 5 had their final visit at 66-78 months and 19 were tested at 96 months. Sham eyes (open circles) showed an average decline in total sensitivity of 475 dB over 96 months (59 dB/yr). Eyes retaining the implant (solid squares) showed greater loss in total visual field sensitivity through month 42 (351 dB versus 266 dB in sham). By month 54, total loss in eyes retaining the implant was comparable to that in sham eyes and remained so through month 96. In eyes where the ciliary neurotrophic factor device was explanted at 24 months (solid circles), there was a plateau in loss between 24 and 40 months. Beyond 42 months, total visual field loss was comparable in explanted eyes to sham eyes.

Figure 1.

Mean decrease in total Humphrey visual field sensitivity over time in a subset of 24 patients with retinitis pigmentosa participating in the CNTF4 trial. All patients received the ciliary neurotrophic factor implant in 1 eye. Ten patients elected to have the implant removed at 24 months (explant); 14 patients chose to retain the implant (no explant).

Measures of macular volume were obtained from all eyes on the final visit. Eight patients had cystoid macular edema (CME) in one or both eyes and were excluded from the volume analysis. Among those without CME, macular volume was comparable (P = 0.41) between treated (7.22 mm3) and sham (7.15 mm3) eyes.

Discussion

CNTF3 and CNTF4 studies showed that long-term exposure to potential therapeutic agents could be safely achieved through encapsulated-cell implants.1 While the surgical procedure was well tolerated and there were no serious adverse events related to the implantation or to the active study agent, there was no evidence of efficacy in the randomized studies. Indeed, visual field sensitivity declined more in treated eyes than in sham eyes, perhaps due to documented effects on phototransduction processes.9,12,18 While these findings substantially reduced enthusiasm for ciliary neurotrophic factor as a therapy for retinitis pigmentosa, the possibility remained that reduced visual sensitivity was an unavoidable consequence of mechanisms that ultimately promote cell survival. Thus, for example, ERGs are reduced by ciliary neurotrophic factor in mouse models of RP, but cell structure is nevertheless preserved months after the exposure.12,14 Cone preservation in ciliary neurotrophic factor-treated eyes compared with the sham-treated fellow eyes was evident in a subset of CTNF4 participants imaged with AOSLO at 30 to 60 months post implant.15,16 Thus we were motivated to evaluate structure and function of patients with RP many years after exposure to ciliary neurotrophic factor.

The results showed no evidence of long-term benefit to visual function, based on either visual acuity or visual field. Eyes retaining the ciliary neurotrophic factor implant showed more rapid loss of visual sensitivity than sham eyes until about 60 months following implant surgery. In patients studied with AOSLO, however, cone density was higher in treated eyes than in sham eyes.15,16 Longitudinal AOSLO measures will be necessary to better understand the relationship between visual sensitivity and cone structure in treated eyes. It is not known exactly how long the encapsulated-cell implants continue to release ciliary neurotrophic factor. In devices that have been explanted, higher-dose capsules produced twice the ciliary neurotrophic factor at 12 months than at 24 months.1 Ciliary neurotrophic factor is still produced by capsules explanted at 50 months, but the output is much lower. It is reasonable to expect that the output has dropped to near zero by 60 months. Beyond 60 months, the rates of visual sensitivity decline in eyes retaining capsules, explanted eyes, and sham eyes were comparable.

Limitations of the study include the fact that patients were no longer masked to treatment assignment after 24 months, which may have biased subjective measures such as visual acuity and visual field sensitivity. In addition, only a subset of patients were available for long-term follow up after the 30 month CNTF4 study ended, and the data do not include patients who did not return for longitudinal evaluation. Finally, follow up occurred at varying intervals determined by the treating physician.

These results provide important long-term visual field progression data for a representative sample of patients with relatively preserved fields at baseline. The annual decline in the sham eyes was 59 dB/year. For patients with an average total field sensitivity of 1148 dB at baseline, this translates into a 5.2% loss per year. This rate of decline for the present sample of patients without genetic typing compares with a 6.9% loss per year for total field sensitivity 20,21 or 4.7% loss per year for visual field area22 in patients with XLRP.

Roughly half of these patients elected to have the capsules removed at 24 months. At 6 months post explant, total visual sensitivity loss was comparable to the sham-treated eyes, again consistent with a reversible decrease in sensitivity directly attributable to ciliary neurotrophic factor. By the final visit at an average 80 months, there were no significant differences in total sensitivity loss among sham-treated eyes, eyes retaining implants and eyes that were explanted.

Ciliary neurotrophic factor demonstrated a significant biological effect in increased macular volume in treated eyes at 12 months.1 While these measures were obtained before the wide availability of spectral domain OCT, and SDOCT was not available at baseline, it was possible to compare treated and sham eyes in a subset of patients at one site. It was found that the increase in volume at 12 months was primarily due to increased thickness of the outer layer complex1, which appeared to parallel outer nuclear layer protection in the rat, dog, and rabbit models. We repeated macular volume measurements on the final visits of patients followed here and found no significant differences among groups, although the small number of patients limited our power to detect a small difference. Thus the increased macular volume in the presence of ciliary neurotrophic factor was not evident when ciliary neurotrophic factor was no longer present.

In conclusion, we found no evidence for long-term benefit to visual acuity, visual field sensitivity or macular structure in patients with RP treated with ciliary neurotrophic factor. While encapsulated cell intraocular implants have been shown to be a practical delivery device, an effective therapeutic agent for delivery remains to be identified.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: Supported by R01EY09076 (DGB), the Foundation Fighting Blindness (DGB, JLD, MEP, RGW), K08EY021186 (MEP), Research to Prevent Blindness Career Development Award (MEP), Nelson Trust Award for Retinitis Pigmentosa (JLD), R01-FD004100 (JLD) and unrestricted Research to Prevent Blindness grants to Casey Eye Institute and UCSF. Neurotech USA, Inc., Cumberland, Rhode Island supported the original CNTF4 trial.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: Acucela, AGTC, Shire Human Genetic Therapies, Ionis Pharmaceuticals, QLT Phototherapeutics, Thrombogenics (DGB), Ionis Pharmaceuticals, Neurotech USA, Inc., Ocugen, Inc., Shire Human Genetic Therapies, Inc., California Institute for Regenerative Medicine, QLT Phototherapeutics (JLD), AGTC, Sanofi-Fovea (RGW), Ionis Pharmaceuticals, Spark Therapeutics, AGTC, ProQR Therapeutics, Sanofi, CRF (MEP).

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Birch DG, Weleber RG, Duncan JL, Jaffe GJ, Tao W. Ciliary Neurotrophic Factor Retinitis Pigmentosa Study G. Randomized trial of ciliary neurotrophic factor delivered by encapsulated cell intraocular implants for retinitis pigmentosa. Am J Ophthalmol. 2013;156(2):283–292. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2013.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sieving PA, Caruso RC, Tao W, et al. Ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF) for human retinal degeneration: phase I trial of CNTF delivered by encapsulated cell intraocular implants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(10):3896–3901. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600236103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stahl N, Yancopoulos G. The tripartite CNTF receptor complex: Activation and signaling involves components shared with other cytokines. J Neurobiol. 1994;25:1454–1466. doi: 10.1002/neu.480251111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wahlin KJ, Campochiaro PA, Zack DJ, Adler R. Neurotrophic Factors Cause Activation of Intracellular Signaling Pathways in Mu ¨ ller Cells and Other Cells of the Inner Retina, but Not Photoreceptors. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:927–936. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beltran WA, Zhang Q, Kijas JW, et al. Cloning, mapping, and retinal expression of the canine ciliary neurotrophic factor receptor α (CNTFRα) Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44(8):3642–3649. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Faktorovich EG, Steinberg RH, Yasumura D, Matthes MT, LaVail MM. Photoreceptor degeneration in inherited retnal dystrophy delayed by basic fibroblast growth factor. Nature. 1990;347(6288):83–86. doi: 10.1038/347083a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.LaVail MM, Unoki K, Yasumura D, Matthes MT, Yancopoulos GD, Steinberg RH. Multiple growth factors, cytokines and neurotrophins rescue photoreceptors from the damaging effects of constant light. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89(23):11249–11253. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.23.11249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McDonald NQ, V CM. Structural determinants of neurotrophin action. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(34):19669–19672. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.34.19669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cayouette M, Gravel C. Adenovirus-mediated gene transfer of ciliary neurotrophic factor can prevent photoreceptor degeneration in the retinal degeneration (rd) mouse. Hum Gene Ther. 1997;8(4):423–430. doi: 10.1089/hum.1997.8.4-423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cayouette M, Behn D, Sendtner M, Lachapelle P, Gravel C. Intraocular gene transfer of ciliary neurotrophic factor prevents death and increases responsiveness of rod photoreceptors in the retinal degeneration slow mouse. J Neurosci. 1998;18(22):9282–9293. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-22-09282.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tao W, Wen R, Goddard MB, et al. Encapsulated cell-based delivery of CNTF reduces photoreceptor degeneration in animal models of retinitis pigmentosa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43(10):3292–3298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liang FQ, Aleman TS, Dejneka NS, et al. Long-term protection of retinal structure but not function using RAAV.CNTF in animal models of retinitis pigmentosa. Mol Ther. 2001;4(5):461–472. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2001.0473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liang FQ, Dejneka NS, Cohen DR, et al. AAV-mediated delivery of ciliary neurotrophic factor prolongs photoreceptor survival in the rhodopsin knockout mouse. Mol Ther. 2001;3(2):241–248. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2000.0252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bok D, Yasumura D, Matthes MT, et al. Effects of adeno-associated virus-vectored ciliary neurotrophic factor on retinal structure and function in mice with a P216L rds/peripherin mutation. Exp Eye Res. 2002;74(6):719–735. doi: 10.1006/exer.2002.1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Talcott KE, Ratnam K, Sundquist SM, et al. Longitudinal study of cone photoreceptors during retinal degeneration and in response to ciliary neurotrophic factor treatment. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(5):2219–2226. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miao I, Bhakta A, Sredar N, et al. In vivo examination of cone photoreceptors in patients with retinitis pigmentosa implanted over five years ago with encapsulated ciliary neurotrophic factor. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55(E-Abstract):2619. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bush RA. Encapsulated Cell-Based Intraocular Delivery of Ciliary Neurotrophic Factor in Normal Rabbit: Dose-Dependent Effects on ERG and Retinal Histology. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45(7):2420–2430. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rhee KD, Ruiz A, Duncan JL, et al. Molecular and cellular alterations induced by sustained expression of ciliary neurotrophic factor in a mouse model of retinitis pigmentosa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48(3):1389–1400. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beck RW, Moke PS, Turpin AH, et al. A computerized method of visual acuity testing: adaptation of the early treatment of diabetic retinopathy study testing protocol. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;135(2):194–205. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(02)01825-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoffman DR, Hughbanks-Wheaton DK, Spencer R, et al. Docosahexaenoic Acid Slows Visual Field Progression in X-Linked Retinitis Pigmentosa: Ancillary Outcomes of the DHAX Trial. Investig Opthalmology Vis Sci. 2015;56(11):6646. doi: 10.1167/iovs.15-17786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Birch DG, Anderson JL, Fish GE. Yearly rates of rod and cone functional loss in retinitis pigmentosa and cone-rod dystrophy. Ophthalmology. 1999;106(2):258–268. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sandberg MA, Rosner B, Weigel-DiFranco C, Dryja TP, Berson EL. Disease course of patients with X-linked retinitis pigmentosa due to RPGR gene mutations. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48(3):1298–1304. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-0971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]