Abstract

Objective

To describe changes in sleep quality in family caregivers of ICU survivors from the patients’ ICU admission until 2 months post-ICU discharge.

Design

Descriptive repeated measure design

Setting

Academic hospital medical ICU

Main outcome measures

Subjective sleep quality (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index [PSQI]) and objective sleep/wake variables (SenseWear Armband™) were measured in family caregivers at patients’ ICU admission, within 2 weeks post-ICU discharge, and 2 months post-ICU discharge.

Results

In 28 family caregivers of ICU survivors, most caregivers reported poor sleep quality (i.e., PSQI > 5) across the three time points (64.3 % during patients’ ICU admission, 53.6 % at each post-ICU time point). Worse trends in sleep quality and objective sleep/wake pattern were observed in caregivers who were employed, and a non-spouse. There were trends of worsening sleep quality in caregivers of patients unable to return home within 2 months post-ICU discharge compared to patients able to return home.

Conclusions

Poor sleep quality was highly prevalent and persisted in family caregivers of ICU survivors for 2 months post-ICU discharge. Our data support the need for a larger longitudinal study to examine risk factors associated with sleep quality in family caregivers of ICU survivors to develop targeted interventions.

Keywords: Intensive care unit, intensive care unit survivors, family caregivers, sleep, post intensive care outcomes

Introduction

Promoting physical and mental health of family caregivers is an important component of family-centered critical care nursing. Psychological symptoms commonly experienced by family members of intensive care unit (ICU) survivors include depression, post -traumatic stress and complicated grief, a constellation of symptoms referred to as Post-ICU Syndrome-Family (PICS-F) (Davidson et al. 2012). Poor sleep quality and impaired sleep/wake patterns may be major contributing factors leading to PICS-F.

Inadequate rest is a highly prevalent health risk in family members of critically ill patients admitted to an ICU (Choi et al. 2013). During the patient’s ICU stay, family caregivers report poor sleep quality and its association with decreased daytime functioning (Verceles et al. 2014). The nature of recovery after critical illness is complex and unpredictable (Unroe et al. 2010), with many caregivers assuming responsibility for patients’ physical and psychological needs (Choi 2009, Van Pelt et al. 2007). In addition, patients may experience several transitions between care settings during recovery, providing additional stress (Unroe et al. 2010). Stress from these increased responsibilities and the unpredictable nature of the recovery may cause persistent problems with sleep quality. Few studies have explored sleep quality or objective sleep/wake patterns in family caregivers during the post-ICU discharge period, an important phenomenon to explore when designing interventions to address PICS-F.

The aim of this report was to describe the trajectory of sleep quality and objective sleep/wake patterns in family caregivers of ICU survivors from the patients’ ICU hospitalization to 2 months post-ICU discharge. We also described sleep quality and objective sleep/wake patterns by caregiver characteristics and patient home discharge status. We hypothesized that poor sleep quality and disrupted sleep/wake patterns would be present across the phases of patients’ illness and recovery and vary depending on characteristics of patients’ recovery (e.g., timing of home discharge after ICU discharge).

Methods

Design and setting

This descriptive analysis was part of a longitudinal study that explored biobehavioral stress responses in family caregivers of critically ill adults who required mechanical ventilation (≥ 4 days) in a medical ICU in a tertiary academic hospital (Choi 2009). Potentially eligible family caregivers and patients were identified by ICU staff and asked to give permission to be approached by a research team member. If permission was granted, a member of the research team verified eligibility and explained the study’s purpose, risks and benefits. Baseline data collection occurred during the patients’ ICU hospitalization. Follow up data collection occurred at various locations at each time point, depending on patients’ placement after hospital discharge.

Data collection

Medical records were reviewed to obtain patient characteristics. Two instruments were used to assess caregiver sleep. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) measured subjective sleep quality (Buysse et al. 1989). The potential PSQI score ranges from 0 to 21; scores over 5 indicate poor sleep quality. Higher scores indicate worse sleep quality. Reliability and validity have been well established (Backhaus et al. 2002, Buysse et al. 1989, Carpenter & Andrykowski 1998, Fichtenberg et al. 2002). The Cronbach’s α reported for the Global PSQI score was 0.83 (Buysse et al. 1989). The Cronbach’s α in a population of ICU family caregivers has not yet been established. The Cronbach’s α for our caregiver sample across three time points was 0.76 – 0.82. The SenseWear Armband™ (SWA; Body Media Inc., Pittsburgh, PA) measured objective sleep/wake patterns. The SWA is an accelerometer with two-axis microelectronic mechanical and heat sensors that allows assessment of activity and sleep. The SWA calculates the sleep/wake variables of total sleep time (TST), sleep efficiency (SE) and wake after sleep onset (WASO). Validity of the SWA In estimating TST, SE and WASO was confirmed in studies that found no significant differences in evaluation these sleep/wake variables between the SWA with either polysomnography or Actiwatch actigraphy (Alsaadi et al. 2014, Sharif & Bahammam 2013).

Both PSQI and SWA were measured at the following three time points: (1) enrollment which occurred during patients’ ICU admission after the patient was on mechanical ventilation for 4 days or longer; (2) within 2 weeks post-ICU discharge, a period requiring initial adjustment following ICU discharge; and (3) 2 months post-ICU discharge, a time point when a majority of patients were discharged to home and challenges to caregivers tend to diversify by patients’ care situations (e.g., home or institution, level of physical care needs).

The PSQI was administered face-to-face or via telephone, depending on caregiver preference. Administering the PSQI via telephone interview has been validated in previous studies (Lequerica et al. 2014, Monk et al. 2013, Tomfohr et al. 2013). If a caregiver preferred telephone-administration of the PSQI, a copy of the response options in each item was provided for reference during the phone call. Caregivers wore the SWA for 72 hours (except when bathing or swimming). Data recorded by SWA were downloaded and analyzed using manufacturer software.

Caregivers’ depressive symptoms and caregiving burden

Shortened version of Center for Epidemiology Study Depression subscale with 10 items (CESD-10) was used to measure depressive symptoms in caregivers (Radloff 1977). The CESD-10 used a 4-point Likert-type summative scale (range 0 – 30). Higher scores indicated more depressive symptoms. Scores of ≥ 8 have been used as a cutoff to indicate clinically significant depressive symptoms (Schulz et al. 2001). Validity has been established in caregivers and healthy adults (Andresen et al. 1994, Logsdon & Teri 1995). The Cronbach’s α reported for the CESD-10 was 0.85 – 0.92 (Choi et al. 2012, Irwin et al. 1999). The Cronbach’s α in our sample was 0.86 – 0.87.

Brief Zarit Burden Interview 12-item (Zarit-12) was used to measure caregiver burden (Bedard et al. 2001). Items in the Zarit-12 described feelings due to caregiving (e.g., feeling strained) using a 5-point Likert-type scale (range 0–48). Higher scores indicated greater burden. Validity in prediction of depressive symptoms was reported in caregivers of community dwelling elderly (O’Rourke & Tuokko 2003). The Cronbach’s reported for the Zarit-12 was 0.88 had been reported (Bedard et al. 2001). The Cronbach’s α in our sample was 0.76 – 0.92.

Ethics and formal requirements

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board. All family caregivers and patients (or their proxy) provided informed consent.

Data Analyses

IBM-SPSS v. 19.0 (SPSS, Inc.; Chicago, IL) was used. The Friedman test was used to explore changes in sleep data. When significant changes were found, follow-up pairwise comparisons were performed using a Wilcoxon test. The Least Significant Difference (LSD) procedure was used for pairwise comparisons. Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare sleep quality and objective sleep variables by caregiver characteristics. Spearmans’ rho was used to examine correlation between subjective sleep quality, objective sleep/wake patterns and caregivers’ depressive symptoms and caregiving burden at each time point. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05 (two-tailed). In addition, trends were examined for differences in sleep quality and objective sleep/wake patterns by caregiver characteristics and patients’ recovery.

Results

Of the 47 dyads enrolled, 28 caregivers (96% Caucasian; 79% females; age 49.7 ± 12.8 years) completed measures at all three time points. Nineteen dyads were unable to complete measures due to the patients’ death during the study period (n=11), caregiver withdrawal or lost to contact (n=6) or data not provided for one or more time points (n=2). Participant characteristics, objective and subjective sleep data in caregivers and patients’ home discharge status over 2 months post-ICU discharge are summarized in Table 1. Caregivers were mostly spouses who were employed and working at enrollment. Those who completed all measures were younger (M ± SD = 51.3 ± 16.6 years vs. 61.5 ± 15.3 years, p = 0.04). Except for age, there were no significant differences between dyads who completed all measures and those who did not.

Table 1.

Characteristics of family caregivers (n=28)

| Variables | Mean ± SD or n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 49.7 ± 12.8 |

| Gender, female | 22 (79) |

| Ethnicity, Caucasian | 27 (96) |

| Relationship to patient | |

| Spouse or significant other | 16 (57.1) |

| Adult child | 6 (21.4) |

| Parent or sibling | 6 (21.4) |

| Education, years | 13.9 ± 2.7 (9 – 21) |

| Working full or part time | 17 (60.7) |

| Number of chronic health problems | 1.5 ±1.5 (0 – 6) |

| History of emotional problem, yes◆ | 12 (43) |

| Caregiver sleep quality | |

| PSQI score; PSQI≥ 5 poor sleep quality. | |

| ICU admission | 6.9 ± 4.1; 18 (64.3) |

| ≤ 2 weeks post-ICU discharge | 6.8 ± 4.6; 15 (53.6) |

| 2 months post-ICU discharge | 6.2 ± 3.6; 15 (53.6) |

| Caregiver objective sleep/wake pattern*a | |

| TST, minutes | |

| ICU admission | 328 ± 71 |

| ≤ 2 weeks post-ICU discharge | 368 ± 115 |

| 2 months post-ICU discharge | 351 ± 105 |

| Sleep efficiency, % | |

| ICU admission | 81 ± 11 |

| ≤ 2 weeks post-ICU discharge | 79 ± 11 |

| 2 months post-ICU discharge | 80 ± 12 |

| WASO, minutes | |

| ICU admission | 54 ± 36 |

| ≤ 2 weeks post-ICU discharge | 67 ± 45 |

| 2 months post-ICU discharge | 66 ± 60 |

PSQI, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; ICU, intensive care unit; TST, Total Sleep Time; WASO, Wake After Sleep Onset

Caregivers were asked to answer the item “Have you seen a doctor for emotional, nervous or psychiatric problems?”

Objective sleep/wake pattern measured by SenseWear-Armband™; Sleep quality measured by PSQI

Missing data exist at ICU admission (n=3), ≤2 weeks post-ICU discharge (n=4) and 2 months post-ICU discharge (n=5).

Caregivers’ Sleep from ICU Admission to 2 Months Post-ICU Discharge

Mean PSQI scores were highest during patient ICU admission. While mean PSQI scores tended to decrease following patient ICU discharge, over half of caregivers continued to report a PSQI score above 5. Regarding objective sleep/wake patterns measured by SWA, average TST ranged from 5 hours 28 minutes to 6 hours 7 minutes. Caregivers were awake almost an hour during the night (e.g., mean WASO ranged 54.2 – 66 minutes). The sleep/wake data displayed no statistically significant difference across the time points.

Caregivers’ Sleep by Caregiver Characteristics

PSQI scores and objective sleep/wake data were compared at each time point by caregiver characteristics (e.g., employment, relationship to patient, gender, previous history of emotional problem and age). Descriptive results from this comparison are summarized in Table 3. Caregivers who were employed had significantly lower mean TST at 2 months post-ICU discharge compared to those who were unemployed. Non-spouse caregivers had significantly lower SE than spouse caregivers at 2 weeks post-ICU discharge and 2 months post-ICU discharge. Caregivers who reported a history of being seen by a clinician for an emotional problem had a trend of worse PSQI, WASO, and SE at all time points. However, these trends were not statistically significant except PSQI score at 2 weeks and WASO during ICU admission. In our sample, worse PSQI scores were significantly correlated with worse depressive symptoms and worse caregiving burden at all time points (Table 4). However, no significant correlations were observed between variables indicating objective sleep/wake pattern (e.g., TST, WASO, SE) and caregivers’ depressive symptoms and caregiving burden (Table 4).

Table 3.

Comparison of family caregivers’ sleep at each time point by caregivers’ characteristics

| Caregiver characteristics | PSQI | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICU admission | p | ≤ 2 weeks | p | 2 months | p | |||||

| Gender | Female | 7.23 ± 4.02 | 0.23 | 7.18 ± 4.38 | 0.24 | 6.32 ± 3.72 | 0.74 | |||

| Male | 5.67 ± 4.76 | 5.33 ± 5.50 | 5.67 ± 3.20 | |||||||

| Working full or part time | Yes | 6.35 ± 3.77 | 0.48 | 6.94 ± 4.31 | 0.70 | 6.0 ± 3.48 | 0.67 | |||

| No | 7.73 ± 4.73 | 6.55 ±5.22 | 6.45 ± 3.86 | |||||||

| Relationship to patient | Spouse | 6.76 ± 4.05 | 0.92 | 6.53 ± 4.19 | 0.91 | 6.12 ± 3.50 | 0.83 | |||

| Non-spouse | 7.09 ± 4.48 | 7.18 ± 5.36 | 6.27 ± 3.85 | |||||||

| History of emotional problem | Yes | 8.08 ± 3.72 | 0.28 | 8.50 ± 3.63 | 0.04* | 7.25 ± 3.33 | 0.16 | |||

| No | 6.00 ± 3.72 | 5.50 ± 4.92 | 5.38 ± 3.63 | |||||||

| Caregiver characteristics | TST (minutes)a | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICU admission | p | ≤ 2 weeks | p | 2 months | p | |||||

| Gender | Female | 344 ± 67 | 0.02* | 386 ± 121 | 0.07 | 363 ± 102 | 0.27 | |||

| Male | 263 ± 52 | 300 ± 50 | 284 ± 117 | |||||||

| Working full or part time | Yes | 321 ± 75 | 0.65 | 336 ± 100 | 0.67 | 310 ± 92 | 0.03* | |||

| No | 341 ± 65 | 431 ± 123 | 414 ± 96 | |||||||

| Relationship to patient | Spouse | 339 ± 76 | 0.41 | 394 ± 118 | 0.33 | 354 ± 109 | 0.94 | |||

| Non-spouse | 312 ± 64 | 324 ± 100 | 348 ± 106 | |||||||

| History of emotional problem | Yes | 335 ± 70 | 0.66 | 344 ± 110 | 0.40 | 334 ± 100 | 0.41 | |||

| No | 322 ± 74 | 388 ± 119 | 368 ± 112 | |||||||

| Caregiver characteristics | SE (%)a | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICU admission | p | ≤ 2 weeks | p | 2 months | p | |||||

| Gender | Female | 82 ± 11 | 0.20 | 81 ± 11 | 0.15 | 80 ± 11 | 0.49 | |||

| Male | 75 ± 9 | 74 ± 10 | 83 ± 19 | |||||||

| Working full or part time | Yes | 78 ± 10 | 0.17 | 77 ± 10 | 0.18 | 79 ± 12 | 0.49 | |||

| No | 84 ± 11 | 83 ± 13 | 83 ± 11 | |||||||

| Relationship to patient | Spouse | 84 ± 9 | 0.18 | 83 ± 10 | 0.01* | 84 ± 10 | 0.04* | |||

| Non-spouse | 76 ± 12 | 73 ± 9 | 74 ± 12 | |||||||

| History of emotional problem | Yes | 78 ± 12 | 0.62 | 78 ± 11 | 0.66 | 79 ± 14 | 0.94 | |||

| No | 82 ± 9 | 80 ± 12 | 81 ± 9 | |||||||

| Caregiver characteristics | WASO (minutes)a | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICU admission | p | ≤ 2 weeks | p | 2 months | p | |||||

| Gender | Female | 58 ± 38 | 0.54 | 70 ± 47 | 0.37 | 72 ± 63 | 0.24 | |||

| Male | 40 ± 28 | 56 ± 43 | 35 ± 38 | |||||||

| Working full or part time | Yes | 54 ± 40 | 0.87 | 68 ± 47 | 0.76 | 61 ± 51 | 0.64 | |||

| No | 55 ± 32 | 64 ± 44 | 74 ± 76 | |||||||

| Relationship to patient | Spouse | 49 ± 33 | 0.44 | 63 ± 45 | 0.53 | 55 ± 47 | 0.46 | |||

| Non-spouse | 63 ± 41 | 72 ± 48 | 82 ± 78 | |||||||

| History of emotional problem | Yes | 75 ± 42 | 0.01* | 67 ± 56 | 0.88 | 79 ± 82 | 0.73 | |||

| No | 38 ± 21 | 67 ± 37 | 53 ± 24 | |||||||

≤ 2 weeks, ≤ 2 weeks post-ICU discharge; 2 months, 2 months post-ICU discharge; PSQI, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; ICU, intensive care unit; TST, Total Sleep Time; WASO, Wake After Sleep Onset

Mann-Whitney U test, p < 0.05

Missing data exist at ICU admission (n=3), ≤2 weeks post-ICU discharge (n=4) and 2 months post-ICU discharge (n=5).

Table 4.

Correlations between family caregivers’ sleep, depressive symptoms and caregiving burden at each time point.

| PSQI | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICU admission | ≤ 2 weeks | 2 months | ||||

| r | p | r | p | r | p | |

| CESD-10 | 0.38 | 0.04* | 0.62 | < 0.001* | 0.44 | 0.02* |

| Zarit-12 | 0.45 | 0.02* | 0.54 | 0.003* | 0.59 | 0.001* |

| TST (minutes)a | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICU admission | ≤ 2 weeks | 2 months | ||||

| r | p | r | p | r | p | |

| CESD-10 | 0.07 | 0.73 | −0.15 | 0.48 | 0.19 | 0.43 |

| Zarit-12 | 0.30 | 0.15 | −0.06 | 0.80 | −0.03 | 0.92 |

| SE (%)a | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICU admission | ≤ 2 weeks | 2 months | ||||

| r | p | r | p | r | p | |

| CESD-10 | 0.12 | 0.56 | −0.29 | 0.17 | 0.27 | 0.25 |

| Zarit-12 | −0.02 | 0.92 | −0.19 | 0.38 | −0.02 | 0.95 |

| WASO (minutes)a | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICU admission | ≤ 2 weeks | 2 months | ||||

| r | p | r | p | r | p | |

| CESD-10 | 0.19 | 0.39 | 0.22 | 0.30 | −0.21 | 0.37 |

| Zarit-12 | 0.05 | 0.82 | 0.32 | 0.13 | 0.32 | 0.17 |

≤ 2 weeks, ≤ 2 weeks post-ICU discharge; 2 months, 2 months post-ICU discharge; PSQI, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; ICU, intensive care unit; TST, Total Sleep Time; WASO, Wake After Sleep Onset; CESD-10, Shortened version of Center for Epidemiology Study Depression subscale with 10 items; Zarit-12, Brief Zarit Burden Interview 12-item

Spearman’s rho test, p < 0.05

Missing data exist at ICU admission (n=3), ≤2 weeks post-ICU discharge (n=4) and 2 months post-ICU discharge (n=5).

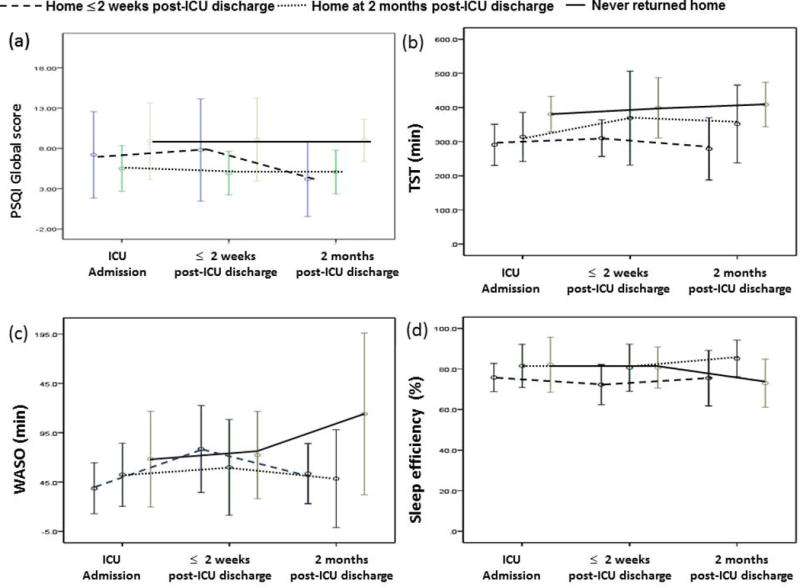

Caregiver Sleep by Timing of Patient Home Discharge for 2 Months Post-ICU Discharge

At 2 months post-ICU discharge, 9 patients (32.1%) had not returned home; 5 patients (17.9 %) were discharged home within 2 weeks and 14 patients (50.0%) were discharged home at 2 months. For caregivers of patients who were not discharged home, all sleep/wake pattern variables showed worsening trends (Figure 1). When discharge home occurred within 2 weeks, mean WASO tended to increase once the patients returned home and then decreased by 2 months post-ICU discharge; and SE improved by 2 months post-ICU discharge.

Figure 1.

Trends of sleep quality and objective sleep/wake patterns in caregivers of ICU survivors by patients’ home discharge status: (1) home ≤ 2 weeks post-ICU discharge, n= 5 (17.9 %); (2) home at 2 months post-ICU discharge, n=14 (50.0%); and (3) never returned home, n=9 (32.1 %). The middle circle represents the mean and error bar refers to standard deviations from the mean.

TST, total sleep time; WASO, wake after sleep onset; PSQI, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index

To determine if there was a difference in caregivers’ sleep related to timing of home discharge, we compared sleep variables between caregivers of the patients who were home within 2 weeks post-ICU discharge (n=5) and caregivers of patients who were home by 2 months post-ICU discharge (n=14) at the point when patients were home (2 weeks and 2 months, respectively). In caregivers whose patients did not return home by 2 months post-ICU discharge, we observed worsening trends in both subjective and objective sleep variables. However, these trends were not statistically significant.

Discussion

Whereas previous studies have reported the negative impact of impaired sleep quality and excessive daytime sleepiness on daytime function among family caregivers during patient ICU hospitalization (Day et al. 2013, Verceles et al. 2014), the present study examined impaired sleep quality and disrupted sleep/wake patterns over a 2-month period following patients’ ICU discharge. Our findings, although preliminary due to the small sample size, provide preliminary evidence in support of our hypothesis that poor sleep quality among family caregivers continues after patients’ discharge from the ICU and varies depending on caregiver characteristics and discharge disposition.

In the present study, both TST and WASO reflected impaired sleep quality. Average TST was less than the average (7–8 hours) reported for the general population (Carskadon & Dement 2011). Mean WASO was greater than the DSM-5 criteria (WASO > 20 – 30 minutes), indicating difficulty maintaining sleep during the night (American Psychiatric Association 2013). In our comparison of caregivers’ sleep quality by caregivers’ characteristics, caregivers who were not a spouse of the patient (e.g., adult children, parents) and worked full- or part-time tended to have worse sleep post-ICU discharge. Moreover, caregivers’ subjective sleep quality was significantly correlated with depressive symptoms and caregiving burden consistently across the time points while the report from the SWA did not show any meaningful correlations.

Although our small sample size limits depicting causal relationship among these characteristics and caregivers’ sleep, our data provides a longitudinal snapshot suggesting (1) working, non-spouse caregivers maybe at high risk for poor sleep quality because of competing demands between caregiver role and their personal and professional lives, and (2) psychological stress and caregiving burden are highly associated with poor subjective sleep quality. We also observed trends of worse sleep quality in caregivers who had history of emotional problems. These results are consistent with reports from multiple studies that support there is a bi-directional relationship between impaired sleep and depressed mood (Buysse 2004, 2014).

Our data also displayed trends in caregiver sleep by patient home discharge status for 2 months post-ICU discharge. Both subjective and objective sleep variables show worsening trends in caregivers of patients who did not return home by 2 months post-ICU discharge. Conversely, among caregivers of patients being discharged to home within 2 weeks post-ICU discharge, both objective and subjective sleep variables were worse than those of caregivers of patients who returned home by 2 months. We speculate that, for caregivers of ICU survivors, prolonged care in a long-term care institution creates psychological stress, predisposing to sleep disturbance. Early home discharge may also create stress by overwhelming caregivers with heightened care demands. If home discharge is the only option due to insufficient insurance, care demands may be further escalated. In our sample, caregivers of patients who were discharged to home within 2 weeks showed trends of worse sleep quality at home discharge than those who had to deal with home discharge at 2 months.

Our data are consistent with prior studies that suggest continued care in an institutional setting may be as stressful as providing care at home (Choi et al. 2011, Im et al. 2004). While caregiving demands may be less on a day-to-day basis, inability to return home signals recovery will be lengthy or not occur. Given the lack of statistical significance, our results are limited in answering whether caregivers’ sleep quality may vary depending on time of home discharge or caregivers’ experience in the post-ICU settings. These are important questions to be answered in future studies in order to identify targets of interventions to support caregivers who may be most vulnerable.

The results of this report are limited by our small sample of mostly Caucasian, female, middle aged family caregivers. Therefore, our results need cautious interpretation considering the imbalance in ethnic, gender and age diversity in our sample. We did not retrospectively assess caregivers’ overall sleep quality prior to patients’ ICU admission or pre-existing sleep disorders (e.g., obstructive sleep apnea and insomnia). Although a previous study reported no significant association between current or past sleep disorders and sleep quality among family caregivers during patient ICU hospitalization (Verceles et al. 2014), it remains unclear whether or not the same results continue during the post-ICU discharge period.

Conclusions

Poor sleep quality was highly prevalent and persisted in caregivers of ICU survivors 2 months post-ICU discharge. In our analysis, subjective sleep quality and report of objective sleep/wake variables (TST, WASO, and SE) were worse when (1) caregivers were required to balance demands of caregiving and work and (2) patients remained in a facility or were discharged home soon after ICU discharge.

Future studies are necessary in a larger diverse sample to further verify risk factors associated with sleep quality in caregivers in conjunction with varied post-ICU transitions by ICU survivors. Targeted interventions based upon caregivers’ risks and needs unique in major post-ICU transition patterns will help improving caregivers’ sleep quality and ultimately benefit patients’ and family recovery.

Table 2.

Characteristics of ICU survivors (n=28)

| Variables | Mean ± SD or n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, years | 51.3 ± 16.6 |

| Gender, male | 20 (71.4) |

| Ethnicity, Caucasian | 27 (96.4) |

| Primary diagnosis | |

| Respiratory | 17 (60.7) |

| Sepsis, Multisystem failure | 3 (10.9) |

| Gastrointestinal, Hepatic | 5 (17.9) |

| Others | 3 (10.8) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Score | 3.4 ± 3.6 |

| APACHE II score | 22.1 ± 8.6 |

| Length of stay in Intensive Care, days | 24.9 ± 12.4 |

| Days on mechanical ventilation, days | 22.1 ± 12.0 |

| Home discharge status | |

| Home ≤ 2 weeks post-ICU discharge | 5 (17.9) |

| Home 2 months post-ICU dischargea | 14 (50.0) |

| Never returned homeb | 9 (32.1) |

APACHE, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation

Prior to home discharge, disposition for these patients included a Long-Term Acute Care Hospital (n=6), hospital step down unit (n=7) and a skilled nursing facility (n=1).

At 2 months post-ICU discharge, disposition for these patients included a Long-Term Acute Care Hospital (n=4), hospital step down unit (n=1) and a skilled nursing facility (n=4).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alsaadi SM, McAuley JH, Hush JM, Bartlett DJ, McKeough ZM, Grunstein RR, Dungan GC, 2nd, Maher CG. Assessing sleep disturbance in low back pain: the validity of portable instruments. PLoS One. 2014;9:e95824. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders DSM-5™. 5th. American Psychiatric Press; Washington, D.C.: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL. Screening for depression in well older adults: evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale) Am J Prev Med. 1994;10:77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backhaus J, Junghanns K, Broocks A, Riemann D, Hohagen F. Test-retest reliability and validity of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index in primary insomnia. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53:737–740. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00330-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedard M, Molloy DW, Squire L, Dubois S, Lever JA, O’Donnell M. The Zarit Burden Interview: a new short version and screening version. Gerontologist. 2001;41:652–657. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.5.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buysse DJ. Insomnia, depression and aging. Assessing sleep and mood interactions in older adults. Geriatrics. 2004;59:47–51. quiz 52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buysse DJ. Sleep health: can we define it? Does it matter? Sleep. 2014;37:9–17. doi: 10.5665/sleep.3298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter JS, Andrykowski MA. Psychometric evaluation of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. J Psychosom Res. 1998;45:5–13. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(97)00298-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carskadon MA, Dement WC. Normal Human Sleep: An Overview. In: Kryger MH, Roth T, Dement W, editors. Princlples and Practice of Sleep Medicine. 5th. Elsevier; Saunders, St. Louis, MO: 2011. pp. 15–26. [Google Scholar]

- Choi CW, Stone RA, Kim KH, Ren D, Schulz R, Given CW, Given BA, Sherwood PR. Group-based trajectory modeling of caregiver psychological distress over time. Ann Behav Med. 2012;44:73–84. doi: 10.1007/s12160-012-9371-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J. Caregivers of Prolonged Mechanical Ventilation: Mind-Body Interaction Model. 2009 Available at: http://projectreporter.nih.gov/project_info_description.cfm?aid=7673131&icde=24939781&ddparam=&ddvalue=&ddsub=&cr=5&csb=default&cs=ASC (accessed Nov 1 2015)

- Choi J, Donahoe MP, Zullo TG, Hoffman LA. Caregivers of the chronically critically ill after discharge from the intensive care unit: six months’ experience. Am J Crit Care. 2011;20:12–22. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2011243. quiz 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J, Hoffman LA, Schulz R, Ren D, Donahoe MP, Given B, Sherwood PR. Health Risk Behaviors in Family Caregivers During Patients’ Stay in Intensive Care Units: A Pilot Analysis. Am J Crit Care. 2013;22:41–45. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2013830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day A, Haj-Bakri S, Lubchansky S, Mehta S. Sleep, anxiety, and fatigue in family members of patients admitted to the intensive care unit: a questionnaire study. Crit Care. 2013;17:R91. doi: 10.1186/cc12736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fichtenberg NL, Zafonte RD, Putnam S, Mann NR, Millard AE. Insomnia in a post-acute brain injury sample. Brain Inj. 2002;16:197–206. doi: 10.1080/02699050110103940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Im K, Belle SH, Schulz R, Mendelsohn AB, Chelluri L. Prevalence and outcomes of caregiving after prolonged (> or =48 hours) mechanical ventilation in the ICU. Chest. 2004;125:597–606. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.2.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin M, Artin KH, Oxman MN. Screening for depression in the older adult: criterion validity of the 10-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:1701–1704. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.15.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lequerica A, Chiaravalloti N, Cantor J, Dijkers M, Wright J, Kolakowsky-Hayner SA, Bushnick T, Hammond F, Bell K. The factor structure of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index in persons with traumatic brain injury. A NIDRR TBI model systems module study. NeuroRehabilitation. 2014;35:485–492. doi: 10.3233/NRE-141141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logsdon RG, Teri L. Depression in Alzheimer’s disease patients: caregivers as surrogate reporters. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43:150–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb06380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monk TH, Buysse DJ, Billy BD, Fletcher ME, Kennedy KS, Begley AE, Schlarb JE, Beach SR. Shiftworkers report worse sleep than day workers, even in retirement. J Sleep Res. 2013;22:201–208. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Rourke N, Tuokko HA. Psychometric properties of an abridged version of The Zarit Burden Interview within a representative Canadian caregiver sample. Gerontologist. 2003;43:121–127. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.1.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff L. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, Beach SR, Lind B, Martire LM, Zdaniuk B, Hirsch C, Jackson S, Burton L. Involvement in caregiving and adjustment to death of a spouse: findings from the caregiver health effects study. JAMA. 2001;285:3123–3129. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.24.3123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharif MM, Bahammam AS. Sleep estimation using BodyMedia’s SenseWear armband in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Ann Thorac Med. 2013;8:53–57. doi: 10.4103/1817-1737.105720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomfohr LM, Schweizer CA, Dimsdale JE, Loredo JS. Psychometric characteristics of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index in English speaking non-Hispanic whites and English and Spanish speaking Hispanics of Mexican descent. J Clin Sleep Med. 2013;9:61–66. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.2342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unroe M, Kahn JM, Carson SS, Govert JA, Martinu T, Sathy SJ, Clay AS, Chia J, Gray A, Tulsky JA, Cox CE. One-year trajectories of care and resource utilization for recipients of prolonged mechanical ventilation: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:167–175. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-153-3-201008030-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Pelt DC, Milbrandt EB, Qin L, Weissfeld LA, Rotondi AJ, Schulz R, Chelluri L, Angus DC, Pinsky MR. Informal caregiver burden among survivors of prolonged mechanical ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:167–173. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200604-493OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verceles AC, Corwin DS, Afshar M, Friedman EB, McCurdy MT, Shanholtz C, Oakjones K, Zubrow MT, Titus J, Netzer G. Half of the family members of critically ill patients experience excessive daytime sleepiness. Intensive Care Med. 2014;40:1124–1131. doi: 10.1007/s00134-014-3347-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]