Abstract

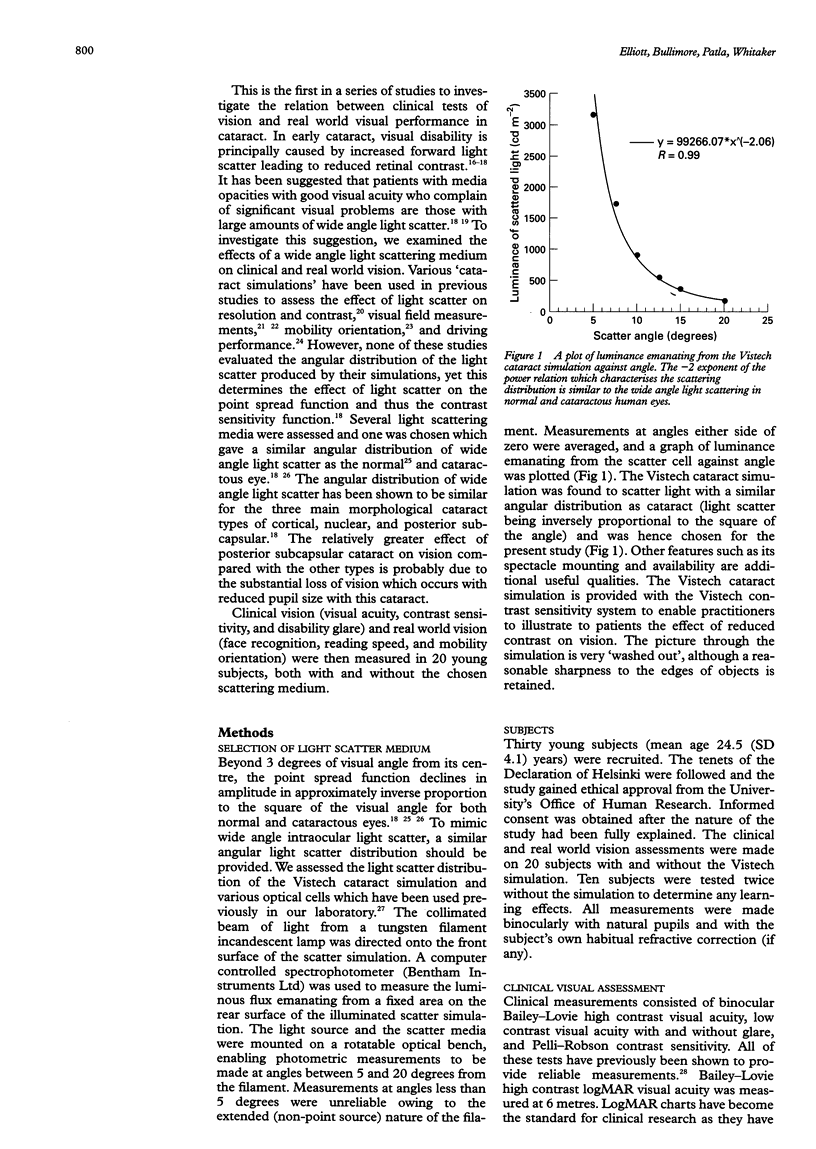

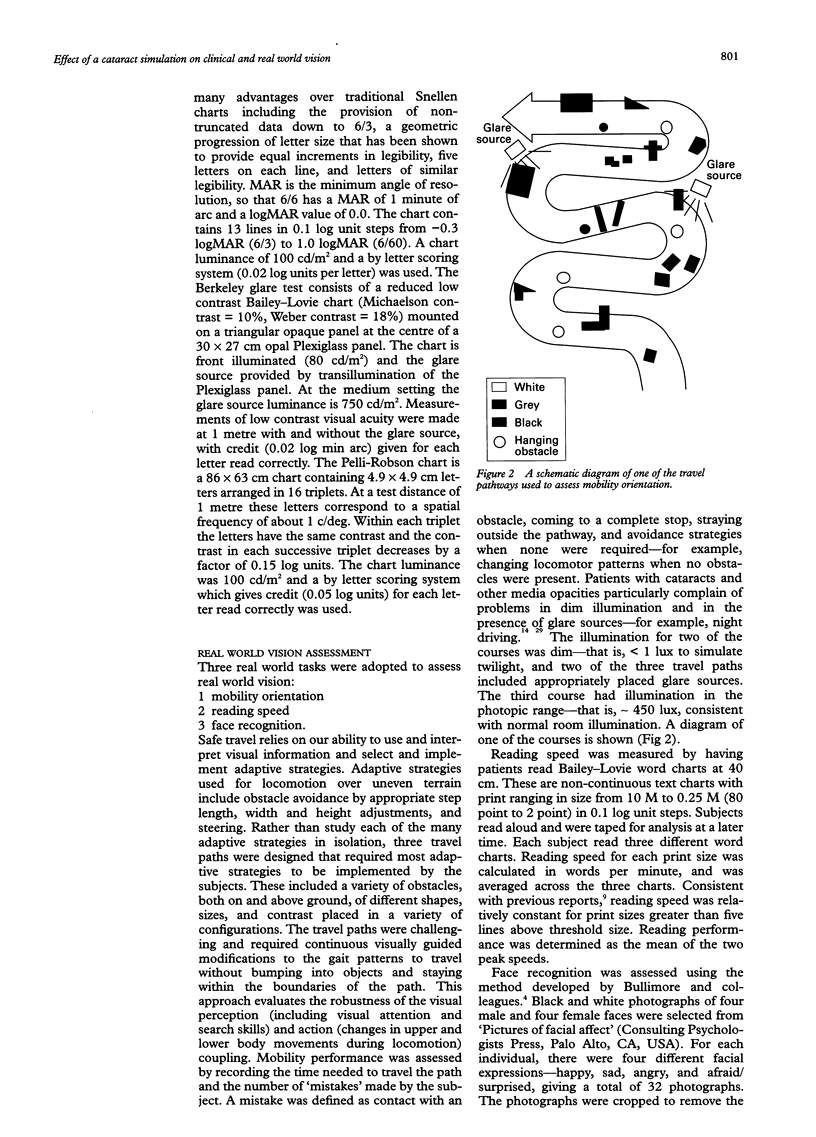

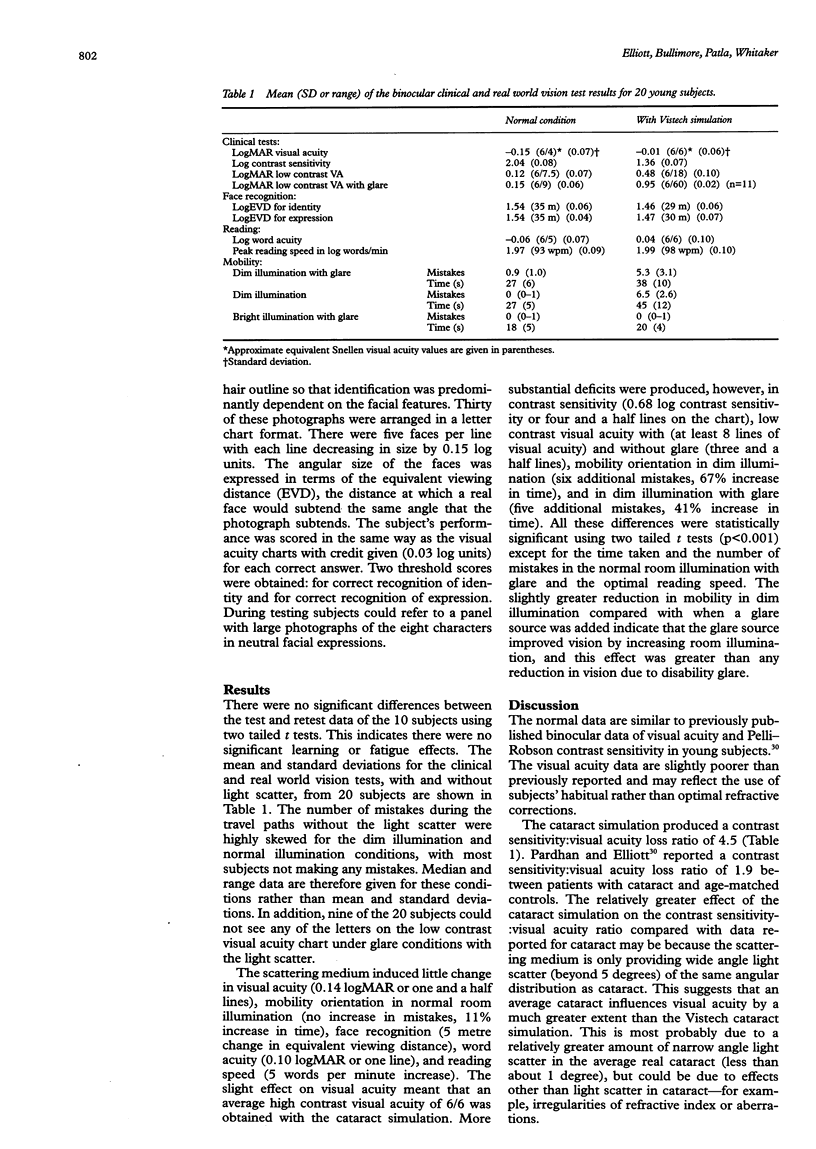

AIMS/BACKGROUND: Many reports have indicated that some patients with cataract can retain good visual acuity but complain of significant visual problems. This is the first in a series of papers trying to determine what causes these symptoms and whether other clinical tests can predict the real world vision loss. METHODS: The effect of a cataract simulation with a similar angular distribution of light scatter as real cataract on clinical (visual acuity, contrast sensitivity, and disability glare) and real world vision (face recognition, reading speed, and mobility orientation) was investigated. RESULTS: The simulation had a relatively small effect on visual acuity (6/6 with the simulation), but much larger effects on contrast sensitivity and low contrast acuity with and without glare. The simulation had no effect on high luminance and high contrast real world tasks, such as mobility orientation in room light and optimal reading speed. A small, but significant deterioration was found for the slightly lower contrast task of face and expression recognition. However, under low luminance conditions, substantial defects in mobility orientation were obtained (despite 6/6 acuity). CONCLUSIONS: Although the relative effect of the cataract simulation on acuity and contrast tasks is not typical of the average cataract, it can be found in those cataract patients with visual problems despite good visual acuity. This corroborates the suggestion that it is large amounts of wide angle light scatter (forward and/or backward) which are at least partly responsible for visual disability in cataract patients with good visual acuity. A patient's reported visual disability may depend on the percentage of time he or she spends under low contrast and/or low luminance conditions, such as walking or reading in dim illumination, and walking or driving at night, in fog, or heavy rain.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Anderson N. B., Cohen H. J. Health status of aged minorities: directions for clinical research. J Gerontol. 1989 Jan;44(1):M1–M2. doi: 10.1093/geronj/44.1.m1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball K., Owsley C. Identifying correlates of accident involvement for the older driver. Hum Factors. 1991 Oct;33(5):583–595. doi: 10.1177/001872089103300509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernth-Petersen P. Visual functioning in cataract patients. Methods of measuring and results. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1981 Apr;59(2):198–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1981.tb02979.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown B., Brabyn L., Welch L., Haegerstrom-Portnoy G., Colenbrander A. Contribution of vision variables to mobility in age-related maculopathy patients. Am J Optom Physiol Opt. 1986 Sep;63(9):733–739. doi: 10.1097/00006324-198609000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown N. A. The morphology of cataract and visual performance. Eye (Lond) 1993;7(Pt 1):63–67. doi: 10.1038/eye.1993.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullimore M. A., Bailey I. L. Reading and eye movements in age-related maculopathy. Optom Vis Sci. 1995 Feb;72(2):125–138. doi: 10.1097/00006324-199502000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullimore M. A., Bailey I. L., Wacker R. T. Face recognition in age-related maculopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1991 Jun;32(7):2020–2029. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott D. B., Bullimore M. A. Assessing the reliability, discriminative ability, and validity of disability glare tests. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1993 Jan;34(1):108–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott D. B. Evaluating visual function in cataract. Optom Vis Sci. 1993 Nov;70(11):896–902. doi: 10.1097/00006324-199311000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott D. B., Hurst M. A., Weatherill J. Comparing clinical tests of visual function in cataract with the patient's perceived visual disability. Eye (Lond) 1990;4(Pt 5):712–717. doi: 10.1038/eye.1990.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuer D. K., Anderson D. R., Knighton R. W., Feuer W. J., Gressel M. G. The influence of simulated light scattering on automated perimetric threshold measurements. Arch Ophthalmol. 1988 Sep;106(9):1247–1251. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1988.01060140407042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holladay J. T., Prager T. C., Trujillo J., Ruiz R. S. Brightness acuity test and outdoor visual acuity in cataract patients. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1987 Jan;13(1):67–69. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(87)80016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch D. D. Glare and contrast sensitivity testing in cataract patients. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1989 Mar;15(2):158–164. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(89)80004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leat S. J., Woodhouse J. M. Reading performance with low vision aids: relationship with contrast sensitivity. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 1993 Jan;13(1):9–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-1313.1993.tb00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legge G. E., Pelli D. G., Rubin G. S., Schleske M. M. Psychophysics of reading--I. Normal vision. Vision Res. 1985;25(2):239–252. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(85)90117-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legge G. E., Rubin G. S., Luebker A. Psychophysics of reading--V. The role of contrast in normal vision. Vision Res. 1987;27(7):1165–1177. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(87)90028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangione C. M., Phillips R. S., Lawrence M. G., Seddon J. M., Orav E. J., Goldman L. Improved visual function and attenuation of declines in health-related quality of life after cataract extraction. Arch Ophthalmol. 1994 Nov;112(11):1419–1425. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1994.01090230033017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marron J. A., Bailey I. L. Visual factors and orientation-mobility performance. Am J Optom Physiol Opt. 1982 May;59(5):413–426. doi: 10.1097/00006324-198205000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owsley C., Sekuler R., Boldt C. Aging and low-contrast vision: face perception. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1981 Aug;21(2):362–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owsley C., Sloane M. E. Contrast sensitivity, acuity, and the perception of 'real-world' targets. Br J Ophthalmol. 1987 Oct;71(10):791–796. doi: 10.1136/bjo.71.10.791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steen R., Whitaker D., Elliott D. B., Wild J. M. Effect of filters on disability glare. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 1993 Oct;13(4):371–376. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-1313.1993.tb00493.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker D., Steen R., Elliott D. B. Light scatter in the normal young, elderly, and cataractous eye demonstrates little wavelength dependency. Optom Vis Sci. 1993 Nov;70(11):963–968. doi: 10.1097/00006324-199311000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood J. M., Wild J. M., Smerdon D. L., Crews S. J. Alterations in the shape of the automated perimetric profile arising from cataract. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1989;227(2):157–161. doi: 10.1007/BF02169790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman J. L., Miller D., Dyes W., Keller M. Degradation of vision through a simulated cataract. Invest Ophthalmol. 1973 Mar;12(3):213–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Waard P. W., IJspeert J. K., van den Berg T. J., de Jong P. T. Intraocular light scattering in age-related cataracts. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1992 Mar;33(3):618–625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]