Abstract

Relapsing polychondritis (RP) is an autoimmune disorder characterized by inflammation in cartilaginous structures including the ears, noses, peripheral joints, and tracheobronchial tree. It rarely involves the central nervous system (CNS) but diagnosis of CNS complication of RP is challenging because it can present with varying clinical features. Herein we report 3 cases of relapsing polychondritis involving CNS with distinct manifestations and clinical courses. The first patient presented with rhombencephalitis resulting in brain edema and death. The second patient had acute cognitive dysfunction due to limbic encephalitis. He was treated with steroid pulse therapy and recovered without sequelae. The third patient suffered aseptic meningitis that presented as dementia, which was refractory to steroid and immune suppressive agents. We also reviewed literature on CNS complications of RP.

Keywords: Relapsing Polychondritis, Meningoencephalitis, Limbic Encephalitis, Dementia

INTRODUCTION

Relapsing polychondritis (RP) is a rare autoimmune disorder characterized by inflammation in cartilaginous structures (1). It mainly involves the cartilage of the ears, nose, larynx, and tracheobronchial tree but it frequently present as a systemic disease showing arthritis, ocular inflammation, audiovestibular involvement, skin lesions, heart valve incompetence, and vasculitis (2). Involvement of central nervous system (CNS) in RP is a fatal condition but it is difficult to diagnose due to rare frequency and variable presentation of disease. There have been papers on CNS involvement of RP but they are few in number and are only sporadic. We have experienced 3 cases of RP with distinct CNS manifestations.

CASE DESCRIPTION

Case 1

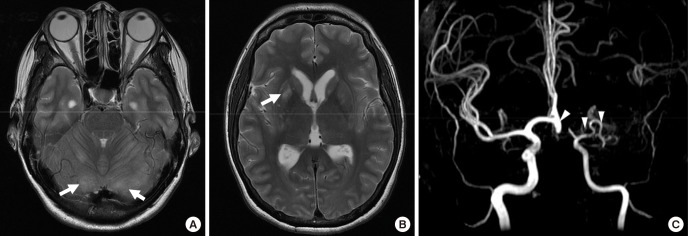

A 48-year-old woman was admitted for severe occipital headache on 22nd April 2014. Two months earlier, she developed bilateral auricular swelling, scleral injection, and fever which responded to oral glucocorticoid. She was diagnosed with RP according to McAdam’s criteria. The headache started 3 days prior and was accompanied by nausea, vomiting, and neck stiffness. On cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination, WBC count was 71 /mm3 (lymphocyte 58%, PMN 28%). Total protein and glucose in CSF were 86.6 mg/dL and 62.9 mg/dL. Stains and cultures for microorganisms were all negative. Serologic tests including antinuclear antibody (ANA), antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA), and rheumatoid factor (RF) were negative. Brain MRI revealed diffuse edema and features of rhombencephalitis: some high signals in parenchyme of bilateral cerebellar hemisphere, cerebellar vermis and bilateral basal ganglia (Fig. 1A and B). Also noted was near complete occlusion of left anterior and middle cerebral, and left distal internal carotid artery but there was no definite sign of infarction (Fig. 1C). She was diagnosed with meningoencephalitis from RP and was treated with methylprednisolone pulse treatment. While on steroid pulse therapy, her headache aggravated continuously. On follow-up CT scan, aggravation of brain edema and compression of ventricle due to increased intracranial pressure (IICP) was noted. Despite treatment to relieve IICP and craniectomy she had rapid deterioration of consciousness and fell into coma. She expired on the 27th hospital day.

Fig. 1.

Brain MRI and MR angiography.

T2 weighted image showed edema of brain cortex and some high signals (arrows) in parenchyma of bilateral cerebellum (A) and basal ganglia (B). MR angiography showed near complete occlusion (arrow heads) of left distal internal carotid artery, left proximal middle cerebral artery, and left anterior cerebral artery (C).

Case 2

A 56-year-old man was admitted with headache and dizziness that developed 3 weeks prior, on 20th July 2012. He had had history of scleritis (3 months ago) and sensory neural hearing loss (1 month ago). On physical examination, there were swelling, erythema, and warmth over both ear helices suggesting active chondritis. Serologic tests including ANA, ANCA, and RF were negative. He was diagnosed with RP based on McAdam’s criteria. While admitted to the hospital, he suddenly developed visual hallucination and agitation. Brain MR imaging was performed immediately but it did not show abnormal findings. On CSF examination, WBC count was 25 /mm3 (lymphocyte 60%, PMN 1%) and total protein and glucose were 61.9 mg/dL and 129.9 mg/dL. Cultures for tuberculosis and ordinary bacteria, and herpes simplex PCR were all negative. There was no malignant cell on CSF cytology. On electroencephalography (EEG), there were frequent brief rhythmic spikes and slow wave complexes, which suggests irritative cerebral dysfunction and partial seizure disorder (Fig. 2). Based on these findings, he was suspected of having limbic encephalitis from RP rather than infection. He was then treated with methylprednisolone pulse therapy and his symptoms gradually improved.

Fig. 2.

Electroencephalography (EEG).

There were frequent brief rhythmic spikes and slow wave complexes on EEG.

Case 3

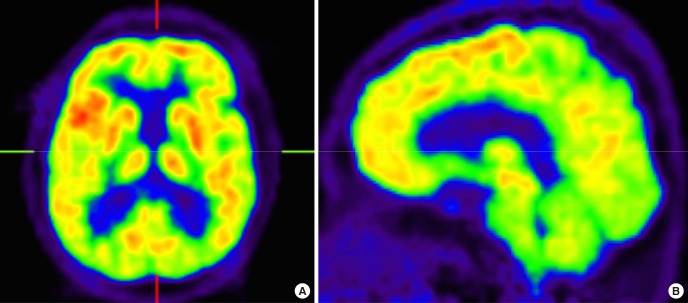

A 48-year-old man who had a 2-month history of loss of memory, difficulty in concentration, and anxiety admitted on 6th November 2008. Seventeen months earlier, he had been diagnosed as having RP due to bilateral auricular chondritis and scleritis. He had several flare-ups and had been treated irregularly. On cerebrospinal fluid examination, WBC count was 18 /mm3 (lymphocyte 74%, PMN 5%), glucose 66.8 mg/dL, and protein were 34.2 mg/dL. Serologic tests including ANA, ANCA, and RF were negative. Brain MR was checked and diffuse mild atrophy of cerebrum was noted but no abnormal signal was observed. PET CT was performed and showed symmetrically decreased FDG uptake in temporal lobe and cerebellum (Fig. 3). Dementia due to aseptic meningitis from RP was suspected. The patient was treated with high dose steroid and methotrexate, and azathioprine was combined consequently. Despite the treatments his symptoms deteriorated and dysphasia, loss of orientation, and behavioral change followed in a few months. As his condition did not improve, he gave up treatment and became lost to follow up.

Fig. 3.

PET-CT scan of brain.

PET-CT scan showed (A) symmetric decreased FDG uptake in both temporal lobe and both cerebellum, and asymmetric decreased FDG uptake in right basal ganglion in axial view, and (B) decreased FDG uptake in posterior cingulate gyrus and precuneus area in sagittal image.

DISCUSSION

Neurological involvement of RP is rare and affects about 3% of patients but it is an important cause of death (3). The pathogenesis of CNS involvement in RP is still unknown but seems to be related with autoimmunity. Autoantibodies to glutamate receptor GluRɛ2 (4) and neutral glycosphingolipids are detectable in the CSF and sera obtained from patients with encephalitis (5). Vasculitis is the major pathological change. In some studies, biopsy showed perivascular lymphocytic cuffing and infiltration in small vessels, with loss of nerve cells and gliosis (6,7). As for clinical manifestations, cranial nerve palsy (V and VII) are the most common form of neurologic manifestations and aseptic meningitis, meningoencephalitis, stroke, and cerebral aneurysm may develop (2).

Meningitis and enephalitis in RP can show various symptoms like cognitive impairment, psychomotor abnormality, confusion, and disorientation (8). Characteristic MRI pattern has not been established but multifocal hyper-intensity lesions, especially in basal ganglia and periventricular and subcortical white matter are the most common findings (7,9,10). Cerebrospinal fluid analysis shows marked pleocytosis with a predominance of PMN but some cases show predominance of lymphocytosis. Sugar level is usually normal and protein is slightly elevated (7,11). In the first case of this report, the patient had meningoencephalitis and imaging and CSF findings were similar to previous reports. One unique aspect of the case was occlusion of cerebral arteries. There have been few reports on combination of meningitis and stroke in RP (12). Stenosis or aneurysmal change due to vasculitis or vascular thrombus formation has been suggested as the cause of stroke in RP (12,13). The prognosis of patients with RP complicated by meningoencephalitis is poor and the reported mortality of meningitis is 12% and that of encephalitis is 36.4% (9).

Limbic encephalitis results from bilateral damage to the medial temporal lobes. It is caused by the herpes simplex virus or by non-herpetic disorders (non-herpetic viruses, Hashimoto’s encephalopathy, CNS lupus, gliomatosis cerebri, intravascular malignant lymphomatosis, and paraneoplastic conditions) (6). RP also is a cause of limbic encephalitis. It can present as cognitive dysfunction, memory impairment, seizures, depression, anxiety and hallucinations (6). In the second case, the patient showed hallucination and agitation, which are symptoms of limbic encephalitis. The findings of EEG, generalized slowing and/or epileptiform activity, also support the diagnosis (14). Though there was no detectable changes in brain MRI, there have been some reports suggesting that it takes time to see a noticeable change on a brain MRI and repeated testing is often required (15,16).

There have been few reports on dementia from RP. The time to develop dementia after diagnosis of RP was a few months to 1 year (16,17,18). In addition to memory loss, changes in behavior, emotional lability, and language and movement abnormalities have been described (16,17,18). Atrophy of cerebral cortex, especially in temporal lobe could be observed in either autopsy or brain MRI. Diffuse vasculitis and gliosis in cerebral cortex, especially in hippocampus was a common pathological feature (16,17). In the third case of our report, the patient had been diagnosed with RP 17 months before the onset of dementia. Similar to previous reports, the CSF finding was compatible with aseptic meningitis.

In regard to diagnosis of RP, McAdam’s criteria require the presence of three or more of the following features: bilateral auricular chondritis, nonerosive seronegative inflammatory polyarthritis, nasal chondritis, ocular inflammation, respiratory tract chondritis, and audiovestibular damage (1). But there have been some modifications on these criteria and some suggest that one McAdam’s criterion and a positive histologic confirmation, or two McAdam’s criteria and a positive response to the administration of corticosteroids or dapsone can suffice the diagnosis (19). In our report, we could not perform cartilage biopsy in all patients and diagnosed RP based on clinical manifestations.

Diagnosis of CNS complication of RP is mainly clinical and is challenging because it can present with varying clinical features. In addition, CNS vasculitis may develop in the absence of detectable systemic vasculitis (18) and complication is not always parallel with the auricular presentation (7).

With regard to treatment of CNS involvement of RP, for it is a very rare complication, treatment is largely empirical. Steroids in high dose or pulse range are the mainstay of treatment. For patients who are refractory to steroid or are requiring long-term steroid therapy, immunosuppressive or cytotoxic treatments are indicated (3,7,12). There have been a few reports in which treatment with TNF blocking agent, infliximab has been effective to CNS involvement resistant to steroid and cytotoxic agents (9,20).

CNS involvement is a very rare complication of RP and diagnosis of this condition is very challenging due to its various presentation and lack of efficient tools. Early suspicion and prompt management may prevent disability and mortality.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE: The author has no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION: Conception and coordination of the study: Jeon CH. Acquisition of data: Jeon CH. Manuscript preparation and approval: Jeon CH.

References

- 1.McAdam LP, O’Hanlan MA, Bluestone R, Pearson CM. Relapsing polychondritis: prospective study of 23 patients and a review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 1976;55:193–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Puéchal X, Terrier B, Mouthon L, Costedoat-Chalumeau N, Guillevin L, Le Jeunne C. Relapsing polychondritis. Joint Bone Spine. 2014;81:118–124. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sampaio L, Silva L, Mariz E, Ventura F. Central nervous system involvement in relapsing polychondritis. Joint Bone Spine. 2010;77:619–620. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2010.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kashihara K, Kawada S, Takahashi Y. Autoantibodies to glutamate receptor GluRepsilon2 in a patient with limbic encephalitis associated with relapsing polychondritis. J Neurol Sci. 2009;287:275–277. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mihara T, Ueda A, Hirayama M, Takeuchi T, Yoshida S, Naito K, Yamamoto H, Mutoh T. Detection of new anti-neutral glycosphingolipids antibodies and their effects on Trk neurotrophin receptors. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:4991–4995. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fujiki F, Tsuboi Y, Hashimoto K, Nakajima M, Yamada T. Non-herpetic limbic encephalitis associated with relapsing polychondritis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75:1646–1647. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2003.035170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang SM, Chou CT. Relapsing polychondritis with encephalitis. J Clin Rheumatol. 2004;10:83–85. doi: 10.1097/01.rhu.0000120900.55459.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Niwa A, Okamoto Y, Kondo T, Nabatame H, Takahashi R, Tomimoto H. Perivasculitic panencephalitis with relapsing polychondritis: an autopsy case report and review of previous cases. Intern Med. 2014;53:1191–1195. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.53.1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garcia-Egido A, Gutierrez C, De la Fuente C, Gomez F. Relapsing polychondritis-associated meningitis and encephalitis: response to infliximab. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2011;50:1721–1723. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ker184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi HJ, Lee HJ. Relapsing polychondritis with encephalitis. J Clin Rheumatol. 2011;17:329–331. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0b013e31822e071b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yaguchi H, Tsuzaka K, Niino M, Yabe I, Sasaki H. Aseptic meningitis with relapsing polychondritis mimicking bacterial meningitis. Intern Med. 2009;48:1841–1844. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.48.2173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsu KC, Wu YR, Lyu RK, Tang LM. Aseptic meningitis and ischemic stroke in relapsing polychondritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2006;25:265–267. doi: 10.1007/s10067-005-1152-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karapanayiotides T, Kouskouras K, Ioannidis P, Polychroniadou E, Grigoriadis N, Karacostas D. Internal carotid artery floating thrombus in relapsing polychondritis. J Neuroimaging. 2015;25:142–144. doi: 10.1111/jon.12088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lawn ND, Westmoreland BF, Kiely MJ, Lennon VA, Vernino S. Clinical, magnetic resonance imaging, and electroencephalographic findings in paraneoplastic limbic encephalitis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78:1363–1368. doi: 10.4065/78.11.1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nara M, Komatsuda A, Togashi M, Wakui H. Relapsing polychondritis with encephalitis: a case report and literature review. Intern Med. 2015;54:231–234. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.54.3568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yan M, Cooper W, Harper C, Schwartz R. Dementia in a patient with non-paraneoplastic limbic encephalitis associated with relapsing polychondritis. Pathology. 2006;38:596–599. doi: 10.1080/00313020601023989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Erten-Lyons D, Oken B, Woltjer RL, Quinn J. Relapsing polychondritis: an uncommon cause of dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79:609–610. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.131425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Head E, Starr A, Kim RC, Parachikova A, Lopez GE, Dick M, Cribbs DH. Relapsing polychondritis with features of dementia with Lewy bodies. Acta Neuropathol. 2006;112:217–225. doi: 10.1007/s00401-006-0098-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang ZJ, Pu CQ, Wang ZJ, Zhang JT, Wang XQ, Yu SY, Shi Q, Liu JX, Huang XL, Fu CJ, et al. Meningoencephalitis or meningitis in relapsing polychondritis: four case reports and a literature review. J Clin Neurosci. 2011;18:1608–1615. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2011.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kondo T, Fukuta M, Takemoto A, Takami Y, Sato M, Takahashi N, Suzuki T, Sato J, Atsuta N, Sobue G, et al. Limbic encephalitis associated with relapsing polychondritis responded to infliximab and maintained its condition without recurrence after discontinuation: a case report and review of the literature. Nagoya J Med Sci. 2014;76:361–368. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]