Abstract

Background/Aims

Twenty-four-hour esophageal impedance and pH monitoring allows detection of all types of reflux episodes and is considered the best technique for identifying gastroesophageal refluxes. However, normative data for the Japanese population are lacking. This multicenter study aimed to establish the normal range of 24-hour esophageal impedance and pH data both in the distal and the proximal esophagus in Japanese subjects.

Methods

Forty-two healthy volunteers (25 men and 17 women) with a mean ± standard deviation age of 33.3 ± 12.4 years (range: 22–72 years) underwent a combined 24-hour esophageal impedance and pH monitoring. According to the physical and pH properties, distal or proximal esophageal reflux events were categorized.

Results

Median 45 reflux events occurred in 24 hours, and the 95th percentile was 85 events. Unlike previous reports, liquid-containing reflux events are median 25/24 hours with the 95th percentile of 62/24 hours. Acidic reflux events were median 11/24 hours with the 95th percentile of 39/24 hours. Non-acidic gas reflux events were median 15/24 hours with the 95th percentile of 39/24 hours. Proximal reflux events accounted for 80% of the total reflux events and were mainly non-acidic gas refluxes. About 19% of liquid and mixed refluxes reached the proximal esophagus.

Conclusions

Unlike previous studies, liquid-containing and acidic reflux events may be less frequent in the Japanese population. Non-acidic gas reflux events may be frequent and a cause of frequent proximal reflux events. This study provides important normative data for 24-hour impedance and pH monitoring in both the distal and the proximal esophagus in the Japanese population.

Keywords: 24-hour esophageal impedance and pH monitoring, Gastroesophageal reflux, Japanese population, Normal values, Proximal reflux

Introduction

Patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) are reported to have a lower quality of life than those with mild heart failure or angina pectoris.1 The prevalence of GERD is reported to be increasing in Japan.2 This is thought to be due to adoption of a western diet and a decrease in the prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection. Accordingly, there is a greater need to elucidate the pathophysiology of GERD in Japanese patients.

Esophageal impedance monitoring is a technique for determining the physical characteristics (liquid, gas, or mixed) of refluxate, and combining impedance monitoring with pH recording makes it possible to assess whether reflux is acidic or non-acidic. One study demonstrated that non-acidic reflux caused GERD symptoms in patients on proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy. Recent studies using this technique have found an association between symptoms and non-acidic reflux in patients with PPI-resistant GERD4 and in patients with non-erosive reflux disease (NERD).5 It has also been reported that gas or gas-containing reflux which reaches the proximal esophagus is an important cause of symptoms in GERD patients, as is pharyngeal gas reflux in patients with reflux laryngitis or chronic cough.6–8 Combined impedance and pH monitoring is the only method with a high sensitivity for detection of all types of reflux.9 Because this technique is becoming important for both research and clinical practice, data on the normal ranges of impedance and pH parameters are needed to distinguish normal from abnormal persons, ie, GERD patients. There have already been some reports of normal values determined in healthy volunteers of other countries.10–14 In a normative study from the USA,11 only liquid-containing (liquid and mixed) reflux was analyzed. In another normative study from Europe,12 gas reflux events were considered separately and were not characterized by pH. All of studies including that from China14 did not analyze precise physical and pH properties in the proximal esophageal reflux events. Moreover, there could be significant differences of normative data between the Japanese population and other populations because of differences in dietary habits or race. Although many Japanese people adopt a western diet, meals are not completely the same as in the western countries. Kawamura et al8 determined normal values for esophageal and pharyngeal reflux events in healthy Japanese volunteers in a study of patients with chronic cough, although the number of volunteers was only 10. However, in their study, the number of liquid and mixed reflux events in the distal esophagus of healthy controls were 8 ± 2 and 10 ± 3, respectively. The median and 95th percentile value of reflux events per 24 hours in the USA study11 were 30 and 75, respectively. Therefore, the number of reflux events in the Japanese population might be less frequent than those in the USA population. Accordingly, we performed a multicenter study to establish the normal ranges of 24-hour esophageal impedance and pH parameters in both the distal and the proximal esophagus in the Japanese population.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

Healthy volunteers were recruited from 4 university hospitals for 24-hour esophageal impedance and pH monitoring. They had no gastrointestinal symptoms, no history of thoracic or digestive surgery, and no medications that could alter gastric acidity or gastroesophageal motility. Subjects with H. pylori infection, known diseases, pregnant women, and breast-feeding women were excluded. All of the subjects underwent upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and were confirmed to have no abnormalities of the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum, as well as no hiatal hernias. We checked for H. pylori infection by measuring the serum level of anti-H. pylori IgG antibody. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of each hospital (approval No.777, UMIN-CTR [University hospital Medical Information Network-Clinical Trials Registry] ID: 000004064). Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects and the study was performed in conformity with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Impedance and pH Monitoring

After the subjects fasted for at least 5 hours, high-resolution esophageal manometry (Manoscan, Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA) was done to exclude esophageal motility disorders according to the Chicago classification ver. 3.015 and to identify the location of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES). Then the subjects underwent 24-hour esophageal impedance and pH monitoring. Impedance was recorded with a combined impedance and pH probe (model ZAN-BG-44; Sandhill Scientific Inc, Highlands Ranch, CO, USA), which was a polyvinyl assembly with a diameter of 2.3 mm containing a series of cylindrical electrodes (each 4 mm in axial length) at 2 cm intervals. The probe was connected to an ambulatory data acquisition unit (Sleuth or ZepHr; Sandhill Scientific Inc), and the sampling frequency of both impedance and pH data was set at 50 Hz. Esophageal and gastric pH were measured with antimony pH electrodes. Before each study, the electrodes were calibrated with 2 buffer solutions (pH 4.0 and pH 7.0). After esophageal manometry, the combined impedance/pH monitoring assembly was inserted nasally under topical anesthesia with 2% Xylocaine jelly (AstraZeneca K.K., Osaka, Japan), and was positioned so that the pH electrodes were located 5 cm above and 10 cm below the LES. With the probe in this position, impedance could be measured at 3, 5, 7, 9, 15, and 17 cm proximal to the upper margin of the LES. Correct positioning of the probe was confirmed by fluoroscopy. Subjects were asked to remain upright during the day and to only lie down at their usual bedtime. They were also instructed to perform their usual activities and to consume three meals during the 24-hour measurement period. Furthermore, they were instructed to press the event marker on the data recorder for meals, body position changes, and symptoms (such as heartburn, regurgitation, and belching) if any.

Just before manometry and 24-hour monitoring, each subject completed the frequency scale for the symptoms of GERD (FSSG), which is a specific questionnaire for assessing GERD that was developed in Japan.16 It consists of 12 questions: a total score of less than 8 is normal while a score equal to or above 8 indicates a diagnosis of GERD.

Data Analysis

After recording was complete, data were transferred to a personal computer for manual analysis with BioView version 5.6.3.0 software (Sandhill Scientific Inc). Data acquired at meal times were excluded from the analysis.

Changes of impedance corresponding to gastroesophageal reflux events were defined from the results of previous human studies.17–19 A liquid reflux event was identified as a decrease of impedance by 50% or more from baseline in at least the 2 distal channels that was propagated retrogradely. Gas reflux was identified as an abrupt increase of impedance by 50% or more from baseline in at least two adjacent channels with simultaneous or near-simultaneous propagation in the retrograde direction. Mixed reflux was defined as a combination of the gas reflux and liquid reflux patterns. Baseline impedance was determined as the average value during a 5-second period immediately before the reflux event.

When esophageal pH recordings were assessed, acidic reflux was defined as a decrease of pH from above 4 to below 4, weakly acidic reflux was defined as a decrease of more than 1 pH unit with a nadir pH above 4, and non-acidic reflux meant no change of pH or a decrease of less than 1 pH unit.8 Reflux events in the proximal esophagus was stratified assuming that the acidity of refluxate in the proximal esophagus was the same as that in the distal esophagus. Superimposed acidic reflux was also analyzed, which was defined as acidic reflux occurring before the esophageal pH had been restored to above 4. All the reflux events were stratified according to its acidity and physical property.

The total acid exposure time was calculated using pH data. When the total distal esophageal acid exposure time, ie, the percentage of time at pH < 4 (% time pH < 4), exceeded 4%, this was considered to be abnormal.

Statistical Methods

According to the physical and pH properties, distal (5 cm above the upper margin of the LES) or proximal (15 cm above the LES margin) esophageal reflux events were categorized. Because reflux events did not show a normal distribution, the data are presented as the median value with the 25th, 75th, and 95th percentiles. Ninety-fifth percentile values are thought to represent the normal range. Statistical analyses of median values were performed by Kruskal-Wallis testing followed by Dunn’s pairwise multiple comparison test. The analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed if data were normally distributed. In all analyses, P < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Profiles of the Subjects

Forty-five healthy volunteers were recruited. Two were excluded because of esophageal motility abnormality by high-resolution manometry (hypertensive peristalsis and weak peristalsis), and 1 was excluded due to abnormal esophageal acid exposure (% time pH < 4 was 6.3%). The remaining 42 healthy volunteers (25 men and 17 women aged 33.3 ± 12.4 [SD] years; range: 22–72 years) were investigated for determination of the normal values of esophageal impedance and pH parameters. The mean body mass index was 21.7 ± 2.2 kg/m2. The FSSG score was determined in 28 subjects and the mean total FSSG score was 2.6 ± 0.4 (range: 0–7).

Reflux Events in the Distal Esophagus

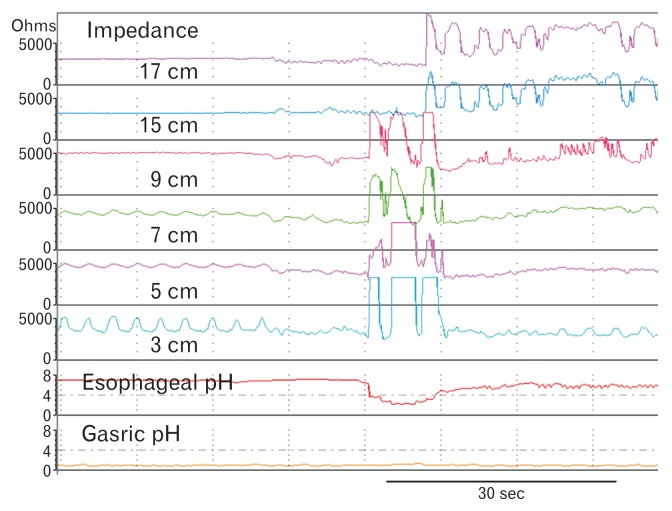

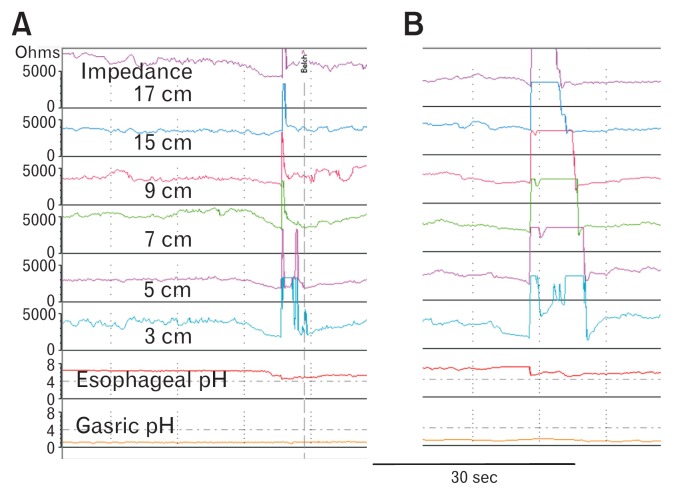

Monitoring was well tolerated by all of the subjects and any important technical failure did not occur. The median reflux events in 24 hours were 45. The median acidic reflux events were 13, the median weakly acidic reflux events were 10, and the median non-acidic reflux events were 20 (Table 1). The median reflux events in the recumbent position were 0, and the median number of reflux events in the upright position was 43 (Table 1). Mixed reflux events (median: 17 [39.5%]) and gas reflux events (median: 17 [39.5%]) were more frequent than liquid reflux events (median: 9 [20.9%]) (Table 2). The number of liquid-containing (liquid and mixed) reflux events was 25. Acidic gas reflux events were observed in the distal esophagus in 6 subjects (median: 2, range: 1–6; Fig. 1) and weakly acidic gas reflux events occurred in 19 subjects (median: 3, range: 1–17; Fig. 2). Superimposed acidic reflux was rare, and was only observed once each in 2 subjects while they were in the upright position.

Table 1.

Gastroesophageal Reflux Events Detected by 24-hour Ambulatory Impedance and pH Monitoring in 42 Healthy Subjects

| All reflux | Acidic reflux | Weakly acidic reflux | Non-acidic reflux | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | ||||

| Median (25th, 75th) | 45 (26, 56) | 11 (4, 20) | 10 (4, 13) | 20 (16, 27) |

| 95th percentile | 85 | 39 | 31 | 67 |

| Upright | ||||

| Median (25th, 75th) | 43 (26, 56) | 10 (4, 17) | 10 (4, 13) | 20 (15, 27) |

| 95th percentile | 84 | 38 | 31 | 67 |

| Supine | ||||

| Median (25th, 75th) | 0 (0, 1) | 0 (0, 0) | 0 (0, 0)) | 0 (0, 0) |

| 95th percentile | 4 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

Table 2.

Characteristics of Gastroesophageal Reflux Determined by Ambulatory 24-hour Impedance and pH Monitoring in 42 Healthy Subjects

| Liquid reflux | Mixed reflux | Gas reflux | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | |||

| Median (25th, 75th) | 9 (4, 13) | 17 (7, 24) | 17 (12, 24) |

| 95th percentile | 26 | 44 | 50 |

| Upright | |||

| Median (25th, 75th) | 8 (4, 13) | 17 (7, 24) | 17 (12, 24) |

| 95th percentile | 25 | 44 | 49 |

| Supine | |||

| Median (25th, 75th) | 0 (0, 0) | 0 (0, 0) | 0 (0, 0)) |

| 95th percentile | 3 | 1 | 1 |

Figure 1.

A representative example of acidic gas reflux. An abrupt increase of impedance was observed in the distal esophagus. At the same time, esophageal pH decreased below 4. The numbers with cm show the distant from upper margin of the lower esophageal sphincter.

Figure 2.

Representative examples of weakly acidic gas reflux. An abrupt increase of the distal and proximal esophageal impedance was observed in both A and B. At the same time, esophageal pH decreased more than 1 pH unit with a nadir pH above 4 in both examples. In A, subject pressed the event marker of belch immediately after the reflux event. The numbers with cm show the distant from upper margin of the lower esophageal sphincter.

Reflux Events in the Proximal Esophagus

As shown in Table 3, 80% (median: 36) of reflux events reached the proximal esophagus. Table 3 also shows the number of reflux events stratified according to acidity in the proximal esophagus. Non-acidic reflux was more frequent than acidic and weakly acidic reflux combined. Reflux events in the proximal esophagus were predominantly gas reflux and the other types of reflux were uncommon (Table 4). In this analysis, almost all gas reflux events that entered the distal esophagus subsequently reached the proximal esophagus (median: 18 [25th, 75th, and 95th percentiles: 10, 24, 52]) and around half of the mixed reflux events in the distal esophagus became gas reflux in the proximal esophagus (10 [3, 21, 42]). Accordingly, the number of gas reflux events was higher in the proximal esophagus than in the distal esophagus (median: 26 vs 17). Compared with gas reflux, mixed reflux and liquid reflux were less likely to reach the proximal esophagus, with only around 18% of mixed reflux events and 20% of liquid reflux events reaching the proximal esophagus. The median number of liquid and mixed reflux events was only 5 (95th percentile 26, 19% of those in the distal esophagus).

Table 3.

Gastroesophageal Reflux Events in the Proximal Esophagus Detected by 24-hour Ambulatory Impedance and pH Monitoring in 42 Healthy Subjects

| All reflux | Acidic reflux | Weakly acidic reflux | Non-acidic reflux | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | ||||

| Median (25th, 75th) | 36 (23, 45) | 7 (3, 13) | 8 (3, 11) | 17 (13, 24) |

| 95th percentile | 73 | 34 | 25 | 56 |

| Upright | ||||

| Median (25th, 75th) | 35 (23, 44) | 7 (3, 13) | 8 (3, 11) | 17 (13, 24) |

| 95th percentile | 73 | 34 | 25 | 56 |

| Supine | ||||

| Median (25th, 75th) | 0 (0, 0) | 0 (0, 0) | 0 (0, 0)) | 0 (0, 0) |

| 95th percentile | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

The proximal esophagus was defined as 15 cm above the lower esophageal sphincter.

Table 4.

Characteristics of Gastroesophageal Reflux Events in the Proximal Esophagus Determined by Ambulatory 24-hour Impedance and pH Monitoring in 42 Healthy Subjects

| Liquid reflux | Mixed reflux | Gas reflux | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | |||

| Median (25th, 75th) | 2 (0, 4) | 3 (0, 9) | 26 (15, 39) |

| 95th percentile | 12 | 19 | 65 |

| Upright | |||

| Median (25th, 75th) | 2 (0, 3) | 1 (0, 6) | 26 (14, 39) |

| 95th percentile | 12 | 12 | 65 |

| Supine | |||

| Median (25th, 75th) | 0 (0, 0) | 0 (0, 0) | 0 (0, 0) |

| 95th percentile | 0 | 0 | 2 |

The proximal esophagus was defined as 15 cm above the lower esophageal sphincter.

The Physical and pH Properties of Reflux Events in the Distal and Proximal Esophagus

In the distal esophagus, acidic reflux events were mainly liquid-containing reflux (pure liquid and mixed), while non-acidic reflux events were mainly gas reflux (Table 5). In the proximal esophagus, acidic reflux events were mainly gas reflux (Table 6).

Table 5.

Gastroesophageal Reflux Events in the Distal Esophagus Stratified by Physical Properties and pH

| All reflux | Acidic | Weakly acidic | Non-acidic reflux | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | ||||

| Median (25th, 75th) | 45 (26, 56) | 11 (4, 20) | 10 (4, 13) | 20 (16, 27) |

| 95th percentile | 85 | 39 | 31 | 67 |

| Liquid | ||||

| Median (25th, 75th) | 9 (4, 13) | 2 (0, 5) | 1 (0, 3) | 2 (1, 6) |

| 95th percentile | 26 | 12 | 9 | 14 |

| Mixed | ||||

| Median (25th, 75th) | 17 (7, 24) | 7 (2, 12) | 3 (0, 6) | 3 (2, 5) |

| 95th percentile | 44 | 31 | 19 | 18 |

| Gas | ||||

| Median (25th, 75th) | 17 (12, 24) | 0 (0, 0) | 3 (0, 6) | 15 (9, 21) |

| 95th percentile | 50 | 4 | 14 | 39 |

Table 6.

Gastroesophageal Reflux Events in the Proximal Esophagus Stratified by Physical Properties and pH

| All reflux | Acidic reflux | Weakly acidic | Non-acidic reflux | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | ||||

| Median (25th, 75th) | 36 (23, 45) | 7 (3, 13) | 8 (3, 11) | 17 (13, 24) |

| 95th percentile | 73 | 34 | 25 | 56 |

| Liquid | ||||

| Median (25th, 75th) | 2 (0, 4) | 0 (0, 2) | 0 (0, 1) | 0 (0, 1) |

| 95th percentile | 12 | 5 | 3 | 5 |

| Mixed | ||||

| Median (25th, 75th) | 3 (0, 9) | 1 (0, 6) | 0 (0, 2) | 0 (0, 1) |

| 95th percentile | 19 | 12 | 5 | 6 |

| Gas | ||||

| Median (25th, 75th) | 26 (15, 39) | 3 (1, 7) | 5 (1, 9) | 16 (9, 24) |

| 95th percentile | 65 | 25 | 22 | 44 |

The proximal esophagus was defined as 15 cm above the lower esophageal sphincter.

pH Findings in the Distal Esophagus

The median % time with pH < 4 over 24 hours was 0.3 % (25th, 75th, and 95th percentiles: 0.1, 0.9, 3.3, range: 0–3.7%), while the median % time with pH < 4 in the upright position was 0.4% (0.1, 1.2, 4.4) and that in the recumbent position was 0 % (0, 0, 2.3).

Effects of Gender

The mean age of the male subjects was 33.9 ± 13.3 (SD) years (range: 22–72) and that of the female subjects was 32.4 ± 11.4 years (range: 22–60), with no significant difference between genders (P = 0.719). Body mass index was significantly higher in male (22.3 ± 2.3 kg/m2) than in women (20.8 ± 1.9 kg/m2) (P = 0.03). Total acid reflux, total acid liquid reflux, total mixed reflux and total acidic mixed reflux events were significantly more frequent in men than in women, and total mixed reflux and weakly acid mixed reflux events in the proximal esophagus were also significantly more frequent in men than in women. The acid exposure time over 24 hours was also significantly longer in men (0.400% vs 0.200%) (Table 7).

Table 7.

Characteristics of Gastroesophageal Reflux Events Stratified by Gender

| Males (n = 25) | Females (n = 17) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total reflux (n) | 45 (39-67-106) | 42 (24-53-82) | 0.078 |

| Total acidic reflux (n) | 13 (5-21-44) | 5 (1-13-39) | 0.035 |

| Total weakly acidic reflux (n) | 10 (8-14-27) | 7 (2-15-31) | 0.182 |

| Total non-acidic reflux (n) | 19 (16-28-76) | 23 (16-28-37) | 0.847 |

| Total liquid reflux (n) | 9 (3-15-30) | 7 (4-10-16) | 0.153 |

| Total acidic liquid reflux (n) | 3 (1-7-13) | 1 (0-3-7) | 0.041 |

| Total mixed reflux (n) | 22 (10-25-43) | 9 (3-22-49) | 0.045 |

| Total acidic mixed reflux (n) | 10 (4-16-31) | 3 (1-9-32) | 0.033 |

| Total gas reflux (n) | 16 (12-29-53) | 19 (15-23-31) | 0.617 |

| Proximal reflux (n) | 38 (29-56-89) | 24 (18-44-73) | 0.118 |

| Proximal mixed reflux (n) | 6 (2-13-26) | 1 (0-6-9) | 0.021 |

| Proximal weakly acidic mixed reflux (n) | 1 (0-3-7) | 0 (0-1-4) | 0.016 |

| Acid exposure time (%) | 0.400 (0.100-1.400-3.600) | 0.200 (0.005-0.400-2.100) | 0.037 |

Data are shown as the median (25th-75th-95th percentiles).

Discussion

Twenty-four hour esophageal impedance and pH monitoring allows detection of all types of reflux episodes8 and is considered to be the best technique to detect reflux and assess the pathophysiology of GERD. Ambulatory impedance and pH monitoring devices are approved and are now widely used in Japan, so that there is an urgent need to establish normal data for the Japanese population.

We detected a median of 45 reflux events in 24 hours, and the 95th percentile for events was 85. Table 8 shows comparison of the number of the esophageal reflux events during 24-hour impedance and pH monitoring among different countries. The corresponding numbers reported by Shay et al,11 Zerbib et al,12 and Xiao et al14 were 30 and 73, 44 and 75, and 40 and 75, respectively, and did not differ much from our results. In our study, the median number of liquid, mixed, and gas reflux events were 9, 17, and 17, respectively, while the corresponding numbers reported by Zerbib et al12 and Xiao et al14 were 20, 17, and 10, and 12, 22, and 4, respectively. The number of liquid-containing reflux (median 25, 95th 62) and acidic reflux (median 10, 95th 31) may be less frequent in Japanese subjects than in those of other countries. These results might be due to difference in diet, race or physique. Although many Japanese people adopt a western diet, meals are not completely the same as in western countries. Fat intake in the Japanese population is far smaller than in western countries.

Table 8.

Comparison of the Esophageal Reflux Events and % Acid Exposure Time During 24-hour Impedance and pH Monitoring Among Different Countries

| Location | Report | All | Acidic | Weakly acidic | Non-acidic | Liquid | Mixed | Gas | % time pH < 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| (median, 95th) | |||||||||

| Distal | Our study, Japan | 45, 85 | 11, 39 | 10, 31 | 20, 67 | 9, 26 | 17, 44 | 17, 50 | 0.3, 3.3 |

| USA11 | 30, 73 | 18, 55 | NA | 9, 26 | NA | NA | NA | 1.2, 6.3 | |

| Belgium-France12 | 44, 75 | 22, 50 | NA | 11, 33 | 20, 55 | 17, 42 | 10, 30 | 0.9, 3.7 | |

| China14 | 40, 75 | 22, 54 | NA | 16, 40 | 12, 46 | 22, 44 | 4, 11 | 0.4, 1.2 | |

| Proximal | Our study, Japan | 36, 73 | 7, 34 | 8, 25 | 17, 56 | 2, 12 | 3, 19 | 26, 65 | - |

In our study, weakly acidic reflux was defined as reflux causing a decrease of more than 1 pH unit with a nadir pH above 4, while non-acidic reflux caused no change of pH or a decrease of less than 1 pH unit. In other studies, non-acidic reflux was defined as reflux with a nadir pH between 4 and 7. The 95th values represent the normal range.

In contrast to liquid-containing reflux, the gas reflux events were more frequent in our study, and that is why our median number of total reflux events was higher than other authors. Balaji et al10 reported that 26.7% of all events were gas reflux events and 65% of all events were non-acidic reflux (using the same definition of non-acidic reflux as ours). In addition, Zentilin et al13 found that gas reflux events accounted for 29% of all reflux events. In our study, about 40% of events were gas reflux, and larger percentage of the gas reflux events in our study is more similar to these two reports than other reports. One explanation for the difference from the findings of other reports12,14 is that our definition of gas reflux was relatively less strict. In the other studies, gas reflux was defined as a simultaneous increase in impedance of > 3000 Ohms in any 2 consecutive impedance channels with 1 channel having an absolute impedance > 7000 Ohms (or 5000 Ohms). In contrast, our definition was an abrupt increase of impedance by 50% or more from baseline in at least 2 adjacent channels with simultaneous or near-simultaneous propagation in the retrograde direction and an actual impedance value was not specified. If the criteria of other studies are adopted, apparent gas reflux events with a belch event marker often cannot be categorized as gas reflux. Also, the sensitivity of automated analysis with BioView software for detection of gas reflux is rather low and it is possible that investigators in previous studies11–14 missed a number of gas reflux events. Gas reflux events are thought to play an important role in several situations.6–9 Bredenoord et al6 reported that symptomatic pure gas reflux was more frequently accompanied by a pH drop (corresponding to our categories of acidic and weakly acidic reflux) than asymptomatic gas reflux in patients with suspected GERD. Therefore, it may be important to detect gas reflux events as completely as possible. Moreover, we observed acidic gas reflux in the distal esophagus of 6 subjects and weakly acidic gas reflux in 19 subjects (Fig. 1 and 2). Such acid-containing gas reflux may cause symptoms in the patients, so we cannot neglect gas reflux events. Zerbib et al12 considered gas reflux events without liquid separately in their study and did not characterize them by pH, but gas reflux events should be analyzed and characterized by pH.

In our volunteers, the median % time pH < 4 over 24 hours was 0.3%, confirming that they were normal. The upper limit of 24-hour esophageal acid exposure in our volunteers was 3.7%, which corresponds to the normal values obtained by traditional 24-hour pH monitoring.20 The corresponding values reported by Shay et al,11 Zerbib et al,12 Zentilin et al,13 and Xiao et al,14 were 1.2%, 0.9%, 0.5%, and 0.4%, respectively. This suggests that the acid exposure time may be shorter in eastern than western populations. It was reported that gastric acid secretion has increased over the past 20 years in Japanese subjects, however, gastric acid secretion is still lower in Japanese subjects than in Europeans or Americans, which may be one reason for lower esophageal acid exposure and smaller number of acidic reflux events in the present study.21

In this study, weakly acidic reflux was defined as a decrease of more than 1 pH unit with the nadir pH remaining above 4, while non-acidic reflux was defined as no change of pH or a decrease of less than 1 pH unit. Because Sifrim et al22 reported the importance of weakly acidic reflux (using the same definition as ours) in patients with suspected GERD, we defineded weakly acidic refluxes separately from non-acidic refluxes. In other studies of normative data12–14 weakly acidic reflux was defined as reflux events with an esophageal pH between 4 and 7, which corresponds to weakly acidic plus non-acidic reflux in our study. In our study, the median number of acidic reflux events and median number of weakly acidic plus non-acidic events over 24 hours was 11 and 30, respectively, while Shay et al,11 Zerbib et al,12 and Xiao et al14 reported that these numbers were 18 and 9, 22 and 11, and 22 and 16, respectively (Table 8). Thus, acidic reflux events may be less frequent, and weakly acidic plus non-acidic events may be more frequent in our study than in the other studies. Table 5 shows that non-acidic reflux was mainly gaseous, while acidic reflux was generally liquid-containing reflux (liquid and mixed reflux), so the reason for the higher number of non-acidic reflux events in the present study is the higher frequency or detection of gas reflux. Our results are in agreement with those of Balaji et al,10 who reported that 59% of reflux events were non-conventional acidic reflux and 58% were gas reflux. We found that 75% of all reflux events were weakly acidic plus non-acidic reflux, which would have not been detected by pH monitoring alone.

In this study, 80% (36 [23, 45, 73]) of reflux events reached the proximal esophagus (15 cm above the LES). According to Shay et al,11 Zerbib et al,12 and Xiao et al,14 the percentage of events reaching the proximal esophagus was 34%, 22%, and 27%, respectively, and these numbers are far lower than our results. This difference can also be explained by the higher number of gas reflux events reaching the proximal esophagus in our study. Because the majority of gas reflux events (87.6%) are reported to reach the proximal esophagus,6 the number of proximal gas reflux events should increase when gas reflux is frequent in the distal esophagus. Moreover, almost half of mixed reflux events in the distal esophagus became gas reflux in the proximal esophagus,7,8 so the number of proximal gas reflux events was higher than that of distal events. In our study, the median number of acidic reflux events and the median number of weakly acidic plus non-acidic events in the proximal esophagus was 7 and 25, respectively, while Xiao et al14 found 6 and 2 events, respectively. We found that non-acidic reflux events in the proximal esophagus were mainly gas reflux events, as was the case in the distal esophagus. The previous studies of normal impedance values10–14 did not describe the physical and pH properties of reflux events in the proximal esophagus, and our study is the first to provide data about the properties of proximal esophageal reflux in a normal population. The median number of proximal liquid plus mixed reflux events was only 5 (95th percentile 26) and accounted for about 19% of distal liquid plus mixed reflux events, so only a few liquid-containing reflux events reached the proximal esophagus in Japanese normal subjects.

The chief limitation of this study was the relatively small number of subjects. The studies of Shay et al,11 Zerbib et al,12 and Xiao et al14 investigated 60, 72, and 70 subjects, respectively. In addition, Balaji et al10 and Zentilin et al13 studied 25 and 17 subjects, respectively, although they used a standard meal. When a standard meal is used, the deviation of data is decreased, but the findings will not have wide applicability because the same standard meal is not always available in clinical practice. Standard meals should be used in clinical research, but cannot always be applicable in clinical practice. Moreover, in the patients study, we believe that the assessment of reflux events after their usual meal is important. Therefore, we did not use a standard meal. Our results were comparable to those obtained in other studies, except for a higher frequency of non-acidic gas reflux. Therefore, the data that we obtained should be applicable as normal values for the Japanese population.

In conclusion, this study detected median 45 reflux events in 24 hours (the 95th percentile was 85) in healthy Japanese subjects. Unlike previous studies, liquid-containing and acidic reflux events may be less frequent which might be due to the difference in diet, race or physique, and non-acidic gas reflux events may be frequent which might be due to the difference in the analysis. We found that 80% of all reflux events reached the proximal esophagus (15 cm above the LES) and these events were mainly non-acidic gas reflux. However, only 19% (5, 26) of liquid and mixed refluxes reached the proximal esophagus. Reflux events were significantly more frequent in men than in women. This study provides important normative data for 24-hour impedance and pH monitoring in the Japanese population.

Acknowledgements

We thank all of the members of IPS (Impedance Study) research committee.

Footnotes

Financial support: None.

Conflicts of interest: None.

Author contributions: Osamu Kawamura: planning and conducting the study, collecting and interpreting data, and drafting the manuscript; Yukie Kohata, Noriyuki Kawami, Hiroshi Iida, Akiyo Kawada, Hiroko Hosaka, Yasuyuki Shimoyama, and Shiko Kuribayashi: collecting data; Yasuhiro Fujiwara, Katsuhiko Iwakiri, Masahiko Inamori, and Motoyasu Kusano: planning and conducting the study; and Micho Hongo: interpreting data and drafting the manuscript.

References

- 1.Dimenäs E, Carlsson G, Glise H, Israelsson B, Wiklund I. Relevance of norm values as part of the documentation of quality of life instruments for use in upper gastrointestinal disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1996;31(sup-pl 221):8–13. doi: 10.3109/00365529609095544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fujiwara Y, Arakawa T. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of GERD in the Japanese population. J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:518–534. doi: 10.1007/s00535-009-0047-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vela MF, Camacho-Lobato L, Srinivasan R, Tutuian R, Katz PO, Castell DO. Simultaneous intraesophageal impedance and pH measurement of acid and nonacid gastroesophageal reflux: effect of omeprazole. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:1599–1606. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.24840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mainie I, Tutuian R, Shay S, et al. Acid and non-acid reflux in patients with persistent symptoms despite acid suppressive therapy: a multicentre study using combined ambulatory impedance-pH monitoring. Gut. 2006;55:1398–1402. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.087668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Savarino E, Zentilin P, Tutuian R, et al. The role of nonacid reflux in NERD: lessons learned from impedance-pH monitoring in 150 patients off therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2685–2693. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.02119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bredenoord AJ, Weusten BL, Curvers WL, Timmer R, Smout AJ. Determinants of perception of heartburn and regurgitation. Gut. 2006;55:313–318. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.074690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kawamura O, Aslam M, Rittmann T, Hofmann C, Shaker R. Physical and pH properties of gastroesophagopharyngeal refluxate: a 24-hour simultaneous ambulatory impedance and pH monitoring study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1000–1010. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.30349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kawamura O, Shimoyama Y, Hosaka H, et al. Increase of weakly acidic gas esophagopharyngeal reflux (EPR) and swallowing-induced acidic/weakly acidic EPR in patients with chronic cough responding to proton pump inhibitors. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;23:411–418. e172. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01658.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sifrim D, Castell D, Dent J, Kahrilas PJ. Gastro-oesophageal reflux monitoring: review and consensus report on detection and definitions of acid, non-acid, and gas reflux. Gut. 2004;53:1024–1031. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.033290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Balaji NS, Blom D, DeMeester TR, Peters JH. Redefining gastro-esophageal reflux (GER) Surg Endosc. 2003;17:1380–1385. doi: 10.1007/s00464-002-8859-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shay S, Tutuian R, Sifrim D, et al. Twenty-four hour ambulatory simultaneous impedance and pH monitoring: a multicenter report of normal values from 60 healthy volunteers. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1037–1043. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zerbib F, des Varannes SB, Roman S, et al. Normal values and day-today variability of 24-h ambulatory oesophageal impedance-pH monitoring in a Belgian-French cohort of healthy subjects. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:1011–1021. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02677.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zentilin P, Iiritano E, Dulbecco P, et al. Normal values of 24-h ambulatory intraluminal impedance combined with pH-metry in subjects eating a Mediterranean diet. Dig Liver Dis. 2006;38:226–232. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2005.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xiao YL, Lin JK, Cheung TK, et al. Normal values of 24-hour combined esophageal multichannel intraluminal impedance and pH monitoring in the Chinese population. Digestion. 2009;79:109–114. doi: 10.1159/000209220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kahrilas PJ, Bredenoord AJ, Fox M, et al. The Chicago Classification of esophageal motility disorders, v3.0. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27:160–174. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kusano M, Shimoyama Y, Sugimoto S, et al. Development and evaluation of FSSG: frequency scale for the symptoms of GERD. J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:888–891. doi: 10.1007/s00535-004-1417-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silny J. Intraluminal multiple electric impedance procedure for measurement of gastrointestinal motility. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 1991;3:151–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.1991.tb00061.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Silny J, Knigge KP, Fass J, Rau G, Matern S, Schumpelick V. Verification of the intraluminal multiple electrical impedance measurement for the recording of gastrointestinal motility. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 1993;5:107–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.1993.tb00114.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fass J, Silny J, Braun J, et al. Measuring esophageal motility with a new intraluminal impedance device. First clinical results in reflux patients. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1994;29:693–702. doi: 10.3109/00365529409092496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mattox HE, 3rd, Richter JE. Prolonged ambulatory esophageal pH monitoring in the evaluation of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Med. 1990;89:345–356. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(90)90348-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kinoshita Y, Kawanami C, Kishi K, Nakata H, Seino Y, Chiba T. Helicobacter pylori independent chronological change in gastric acid secretion in the Japanese. Gut. 1997;41:452–458. doi: 10.1136/gut.41.4.452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sifrim D, Dupont L, Blondeau K, Zhang X, Tack J, Janssens J. Weakly acidic reflux in patients with chronic unexplained cough during 24 hour pressure, pH, and impedance monitoring. Gut. 2005;54:449–454. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.055418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]