Abstract

Scope

Fish oil-derived long-chain monounsaturated fatty acids (LCMUFA) containing chain lengths longer than 18 were previously shown to improve cardiovascular disease risk factors in mice. However, it is not known if LCMUFA also exerts anti-atherogenic effects. The main objective of the present study was to investigate the effect of LCMUFA on the development of atherosclerosis in mouse models.

Methods and results

LDLR-KO mice were fed Western diet supplemented with 2% (w/w) of either LCMUFA concentrate, olive oil, or not (control) for 12 wk. LCMUFA, but not olive oil, significantly suppressed the development of atherosclerotic lesions and several plasma inflammatory cytokine levels, although there were no major differences in plasma lipids between the three groups. At higher doses 5% (w/w) LCMUFA supplementation was observed to reduce pro-atherogenic plasma lipoproteins and to also reduce atherosclerosis in ApoE-KO mice fed a Western diet. RNA sequencing and subsequent qPCR analyses revealed that LCMUFA upregulated PPAR signaling pathways in liver. In cell culture studies, apoB-depleted plasma from LDLR-K mice fed LCMUFA showed greater cholesterol efflux from macrophage-like THP-1 cells and ABCA1-overexpressing BHK cells.

Conclusions

Our research showed for the first time that LCMUFA consumption protects against diet-induced atherosclerosis, possibly by upregulating the PPAR signaling pathway.

Key works: long-chain monounsaturated fatty acids, atherosclerosis, PPAR signaling pathway, inflammation, cholesterol efflux

1. Introduction

Atherosclerosis, a multi-factorial disease involving inflammation and changes in lipid and lipoprotein metabolism components [1], is one of the major underlying causes of cardiovascular disease (CVD). Dietary lipids, by modulating inflammation and lipid metabolism, can have a profound effect on CVD risk. Unlike pro-atherogneic saturated fatty acids (FA), numerous animal and human studies have shown that regular consumption of polyunsaturated FA (PUFA)-rich fish oils have favorable effects on serum lipids, as well as on endothelial function, inflammation, thrombosis and arrhythmia. Most of these beneficial effects have been attributed to n-3 PUFA, namely eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) [2]. Fish oils, however, also contain varying amounts of other unusual types of FAs that are not commonly found in other food sources. For example, oils derived from saury [3] and pollock [4] are all enriched in long-chain monounsaturated FAs (LCMUFA), defined here as monounsaturated fatty acids at least 20 carbons in length (i.e., C20:1 and C22:1 isomers combined). Interestingly, data from the original epidemiologic studies of Greenland Eskimos that first established a link between n-3 PUFA consumption and CVD protection also showed a possible link between LCMUFA consumption and cardiovascular health [5, 6]. Besides n-3 PUFA, levels of LCMUFA were also found to be high in the typical diet and plasma of Greenland Eskimos, who had lower mortality from heart diseases compared with Caucasian Danes and Danish Eskimos. Studies on the association between red blood cell fatty acid levels and incident coronary artery disease in the Physician’s Health Study also showed a strong inverse association between red blood cell LCMUFA levels and CVD, even after adjusting for de novo synthesized MUFAs (C16:1 and C18:1), indicating a possible atheroprotective effect of LCMUFA [7].

We previously reported in animal studies that dietary LCMUFA-rich fish oils have beneficial physiological effects, such as hypolipidemic and anti-inflammatory activities, which were found partly through downregulation of several inflammatory genes and upregulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma (Pparg) and its target genes [3, 4, 8]. PPARs are lipid-activated transcription factors, and accumulating evidence has suggested that activation of PPAR signaling pathways suppresses atherosclerosis progression by regulating lipid and lipoprotein metabolism, decreasing the production of inflammatory cytokines, as well as by direct influences on the vascular wall [9]. Therefore, we hypothesized that LCMUFA consumption, by modulating the PPAR signaling pathway, may protect against diet-induced atherosclerosis.

In the present study, we investigated whether supplementation of LCMUFA to a high-fat diet prevents the development of atherosclerosis in two mouse models and used a MUFA-rich olive oil diet as a control. Most studies on MUFA focus on oleic acid (C18:1), the most abundant MUFA contained in olive oil (~ 60–70%), and multiple studies have demonstrated that oleic acid-rich oil also decreases the risk of coronary artery disease compared with saturated fatty acids [10]. We hypothesized that MUFAs with different carbon chain lengths might have different effects on CVD risk. In terms of the mouse models, we tested the effect of LCMUFA supplementation on both ApoE-KO mice and LDLR-KO mice. ApoE-KO mice develop severe dyslipidemia because of decreased clearance of apoB containing lipoproteins [11], particularly when placed on a high fat diet, and for this model we supplemented their Western diet with a high dose of LCMUFA (5% (w/w)). In contrast, LDLR-KO mice develop less of a severe dyslipidemic phenotype and is closer to human dyslipidemia [11], particularly patients with Familial Hypercholesterolemia with a defective LDL receptor. For these mice, we used a lower and more physiologic dose of LCMUFA, namely Western diet supplemented with 2% (w/w) of either LCMUFA concentrate or olive oil. Results from the present study show for the first time that LCMUFA consumption can have a variable effect on plasma lipoprotein levels dependent on the dose and that it protects against atherosclerosis, possibly by upregulating PPAR signaling pathways.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Ethical Statement

Animal handling and experiments were performed in accordance with guidelines provided by the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. All procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee in the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, or in Tokushima University.

2.2. Animals and experimental design

Eight-week old LDLR-KO female mice and 7-week old ApoE-KO male mice were purchased from Jackson Lab (Bar Harbor, ME). Olive oil was provided by Harlan Teklad (Indianapolis, IN), and LCMUFA concentrate was supplied by Nippon Suisan Kaisha (Tokyo, Japan), with respective fatty acid composition shown in Table 1. LDLR-KO mice were fed on a Western diet TD.88137 Adjusted Calories Diet (Harlan Teklad) supplemented with 2% (w/w) LCMUFA, 2% (w/w) olive oil, or not (control) for 12 weeks. ApoE-KO mice were fed on a Western diet D12079Bpx03 (Research Diets, Inc., NJ) supplemented with 5.2% (w/w) LCMUFA or not (control) for 12 weeks. The compositions of diets for LDLR-KO mice and ApoE-KO mice are shown in Supplemental Table 1 and 2, respectively. The fatty acid composition of each diet used for LDLR-KO mice was shown in Supplemental Table 3. To evaluate plasma lipid profile, retro-orbital bleeds were performed on mice that had been fasted for 5 hrs. At the end of the feeding period, mice from each group were sacrificed and blood was collected in heparinized capillary tubes and plasma was separated from blood samples by centrifugation and stored in aliquots at −80°C for further use.

Table 1.

Fatty acid composition of dietary oils incorporated into mouse diets

| Fatty acids (%) | Olive oil | LCMUFA |

|---|---|---|

| 14:0 | ND | 3.5 |

| 16:0 | 13.7 | 12.8 |

| 16:1(n-7) | 1.2 | 1.3 |

| 18:0 | 2.5 | 3.0 |

| 18:1(n-9) | 71.1 | 4.8 |

| 18:2(n-6) | 10 | 0.8 |

| 18:3(n-3) | 6 | 0.3 |

| 20:0 | ND | 0.4 |

| 20:1(n-11) | ND | 16.8 |

| 20:1(n-9) | ND | 4.7 |

| 20:4(n-6) | ND | 0.1 |

| 20:5(n-3) | ND | 0.2 |

| 22:1(n-11) | ND | 34.8 |

| 22:1(n-9) | ND | 1.5 |

| 22:5(n-3) | ND | 0.2 |

| 22:6(n-3) | ND | 0.4 |

| Total SFA | 16.2 | 19.7 |

| LCMUFA | 0.2 | 57.8 |

| Total MUFA | 72.5 | 63.9 |

| Total n-6 PUFA | 10 | 0.9 |

| Total n-3 PUFA | 6 | 1.1 |

LCMUFA: long-chain monounsaturated fatty acids; MUFA: monounsaturated fatty acids; ND: not detected; PUFA: polyunsaturated fatty acids; SFA: saturated fatty acids.

2.3. Hepatic lipids and fatty acid composition

In LDLR-KO mice, the analyses of hepatic lipid contents and fatty acid composition were described in Supplemental Methods.

2.4. Plasma metabolites and cytokines

Fasting plasma were analyzed for triglycerides (TG), total cholesterol (TC), free cholesterol (FC), and phospholipids (PL), using commercial enzymatic methods (Wako Chemicals USA, Inc., Richmond, VA). LDL cholesterol values in ApoE KO mice were measured by the direct assay (Sekisui Medical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). For LDLR-KO mice, the plasma concentrations of 33 cytokines were measured, using Magnetic Luminex bead-based multiplex assays from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN) by flow cytometry (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Plasma lipoprotein profiles from pooled plasma (n = 12) were analyzed after separation by fast protein liquid chromatography (FPLC), as described previously [12].

2.5. Atherosclerotic lesion analysis

The analysis of atherosclerotic lesion, as well as aortic accumulations of lipid and macrophage was described in Supplemental Methods.

2.6. Total RNA extraction

Total RNA from livers in LDLR-KO mice and aortas in ApoE-KO mice were isolated using an RNeasy Kit (Qiagen Inc., CA) and Illustra RNAspin RNA Isolation Kit (GE Healthcare), respectively, and treated with DNase I (Qiagen) to remove genomic DNA according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The RNA concentration was quantified using a NanoDrop® ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Inc., DE). The quality of the RNA was determined with Agilent 2100 analyzer using RNA 6000 Pico Chip kits. RNA typically had an A260:A230 ratio greater than 1.7, and an A260:A280 ratio of approximately 2.1.

2.7. RNA-Seq library construction and sequencing

For LDLR-KO mice, 10 ng of Total RNA from liver was used as starting material for double strand DNA production using Ovation RNA seqv2 (NuGen, Inc., San Carlos, CA). Following DNA production, Nextera XT DNA library preparation kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA) was used for sequence library preparation. Indexed RNAseq libraries were mixed and subjected to 50 base pair pared-end sequencing on Hiseq2500 (Illumina, San Diego, CA). Sequencing data were demultiplexed and converted to FASTQ format.

2.8. RNA-Seq read mapping pathway analysis

A total of 12 samples were sequenced (4 samples from each group of LDLR-KO mice) with an average of 23 millions of reads over all samples. The RNAseq reads were mapped to the mouse reference genome mm10 with Ensembl annotation NCBIM37 (http://useast.ensembl.org/) by Tophat2 (https://ccb.jhu.edu/software/tophat) with default parameters. The average mapping rate is 80%. Raw counts were then obtained by HTSeq (http://www-huber.embl.de/users/anders/HTSeq). To perform the pathway analysis using KEGG pathways (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/kegg2.html), the Ensembl Gene identifiers were converted to Entrez Gene identifiers by the annotation database org.Mm.eg.db (https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/data/annotation/html/org.Mm.eg.db.html). Differential expression analysis was performed using the Bioconductor tool edgeR (https://www.bioconductor.org/packages/3.3/bioc/html/edgeR.html).With the log2 Fold Change output from edgeR, we performed the gene set enrichment analysis by GSEA with KEGG pathway database downloaded from Bader lab (http://baderlab.org/GeneSets), and genes were pre-ranked by the log2Fold Change.

2.9. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis

To confirm expression changes of vitally important genes in the PPAR pathway obtained from RNA-Seq analysis, we performed qPCR using total RNA from liver samples (Supplemental Methods). Primer sequences are shown in Supplemental Table 4.

2.10. Cell culture

Human THP-1 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and antibiotics and were differentiated into macrophages by adding phorbol 12-myristate 12-acetate (PMA) (100 ng/mL) overnight. BHK cells expressing human ABCA1, ABCG1, or neither (MOCK) were cultured in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% FBS and antibiotics. Cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. All in vitro studies were carried out on standard 24-well plates (300,000 cells/well).

2.11. In vitro cholesterol efflux assay

To estimate HDL function in plasma of mice, cholesterol efflux assays were performed at 37°C in macrophage-like THP-1 cells labelled with [3H]cholesterol for 24 hr. After being washed three times with PBS, the cells were incubated for 4 hr with 1% of plasma previously depleted of apoB-containing lipoproteins by precipitation with polyethylene glycol (MW 8000; Sigma-Aldrich, MO). Each sample was tested in triplicate. For each well, radioactivity was counted in media and cell lysate, and cholesterol efflux was expressed as the % of [3H]cholesterol transferred from cells to medium. We also applied individual LCMUFA isomer to THP-1 cells to estimate the Furthermore, to investigate the roles of ABC transporters in promoting mass cholesterol efflux due to LCMUFA diet, we conducted efflux assays in BHK-ABCA1, BHK-ABCG1, and BHK-mock-transfected cells with a mifepristone inducible gene [13]. BHK-mock-transfected cells that do not express either ABCA1 or ABCG1 were used as controls.

2.12. Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism statistical software (GraphPad Software Inc. version 6.00, La Jolla, CA). Statistical analysis between three groups of LDLR-KO mice was completed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Bonferroni post hoc test where appropriate, and the Student's t-test was used to compare two groups of ApoE-KO mice. All data were expressed as mean ± SEM, and differences were considered significant when P ≤ 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Plasma lipid levels

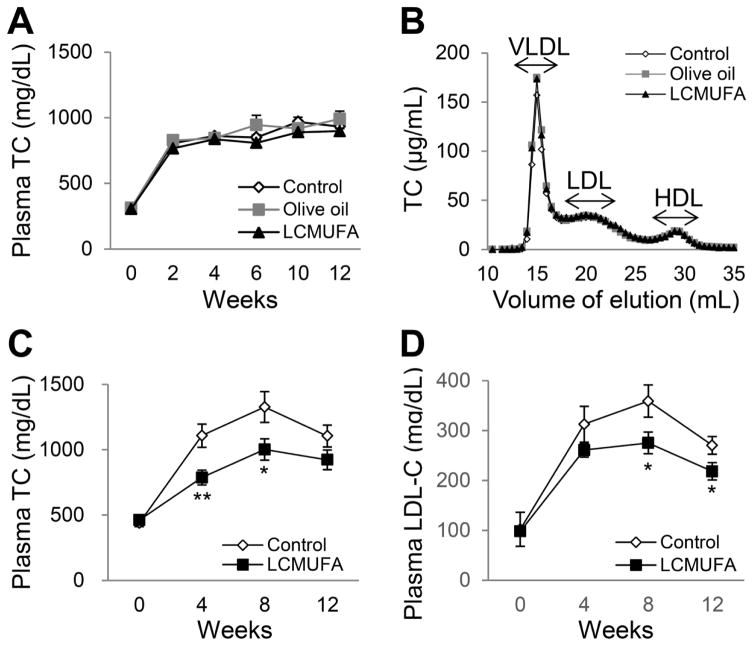

In LDLR-KO mice, the diets supplemented with 2% LCMUFA or olive oil did not differ compared to non-supplemented Western diet on their effect on plasma TC levels (Fig. 1A), as well as TG, FC and PL (data not shown). Analysis of lipoproteins by FPLC analysis also showed no difference in cholesterol on VLDL, LDL, and HDL fractions between the 3 diet groups (Fig. 1B). A the higher dose (5% w/w), LCMUFA, however, did reduce plasma TC and LDL-cholesterol levels significantly at week 4, 8, and 12 (P < 0.05) in ApoE-KO mice (Fig. 1C and 1D), although LCMUFA diet did not affect plasma levels of FC and HDL-cholesterol (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Plasma lipid levels in LDLR-KO mice fed a Western diet supplemented with 2% olive oil, LCMUFA, or not (control), and APOE-KO mice fed a Western diet supplemented with 5% LCMUFA or not (control). (A) Time course of plasma TC levels in LDLR-KO mice (n = 12). (B) FPLC analysis of plasma cholesterol of LDLR-KO at 12 wk. Values of pooled plasma from the twelve mice of each group were used for the data representation (injection volume: 100 μL). (C) Time course of plasma TC levels in ApoE-KO mice (n = 10). (D) Time course of plasma LDL-cholesterol levels in ApoE-KO mice (n = 10). Values represent the means ± SEM. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01 vs. control at the indicated time points.

3.2. Hepatic lipids and fatty acid composition

In LDLR-KO mice, there were no significant differences in hepatic TG and TC contents among the three groups (Supplemental Table 5). Hepatic fatty acid composition analysis revealed that LCMUFA-rich diet significantly increased (P < 0.05) hepatic levels of LCMUFA by ~47.5% compared to control and olive oil diets. In contrast, olive oil ingestion increased oleic acid in liver significantly (P < 0.05) by ~6% compared to control and LCMUFA diets (Supplemental Table 6). There were no differences in total saturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids among the three diet groups.

3.3. Atherosclerosis lesion development

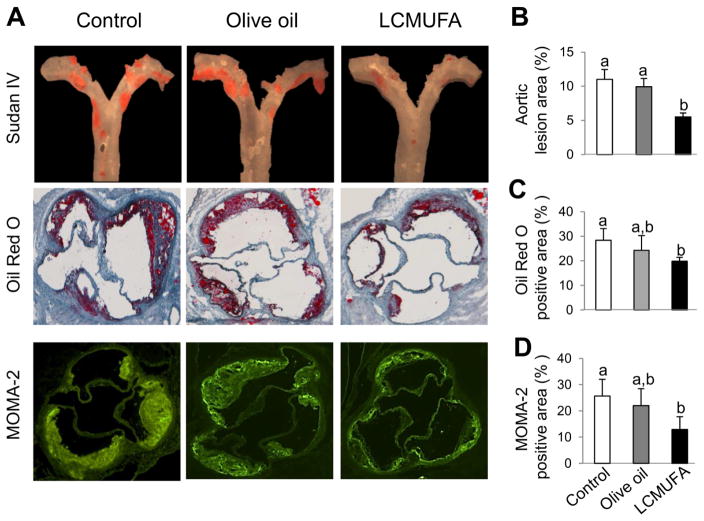

In LDLR-KO mice, the development of atherosclerosis lesions in the LCMUFA group as assessed by total atherosclerotic lesions with en face analysis was significantly suppressed by 50 % (P < 0.05) and 45% (P < 0.05) compared to the control and olive oil groups, respectively. There was no significant difference in atherosclerosis lesion area between the control and olive oil group (Fig. 2A top panel, and Fig. 2B). In addition, we further characterized the plaque composition by staining for lipid deposition and macrophages in serial cross-sections of the aortic sinus, the anatomic site that is most predisposed to atherosclerosis and is often resistant to various therapies [14]. The 2% LCMUFA, but not olive oil, diet significantly suppressed (P < 0.05) the lipid accumulation in aortic sinus by 30% compared to control group as determined by Oil Red O staining (Fig. 2A middle panel, and Fig. 2C). Immunofluorescence staining showed that MOMA-2, a marker for detection of monocytes and macrophages, decreased significantly (P < 0.05) by 50% in LCMUFA group compared to control, although no difference was detected between the control and olive oil group (Fig. 2A bottom panel, and Fig. 2D), although the mRNA expression of genes for intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (Icam-1) and inflammation (Il-6 and Tnfα) in aorta were not different among the three groups (Supplemental Fig. 1).

Figure 2.

Development of atherosclerosis in LDLR-KO mice fed Western diet supplemented with 2% olive oil, LCMUFA, or not (control) for 12 weeks. (A) Representative en face Sudan IV staining of aorta (top panels), cross-sectional Oil Red O staining (middle panels), and cross-sectional MOMA-2 fluorescent immunostaining (bottom panels) of aortic sinus. (B) Quantitative analysis of en face Sudan IV-positive area of aorta (n = 12). (C) Quantitative analysis of cross-sectional Oil Red O-positive area of aortic sinus (n = 5). (D) Quantitative analysis of cross-sectional MOMA-2 positive area of aortic sinus (n = 5). Data are shown as mean ± SEM. Labeled means without a common letter differ, P < 0.05.

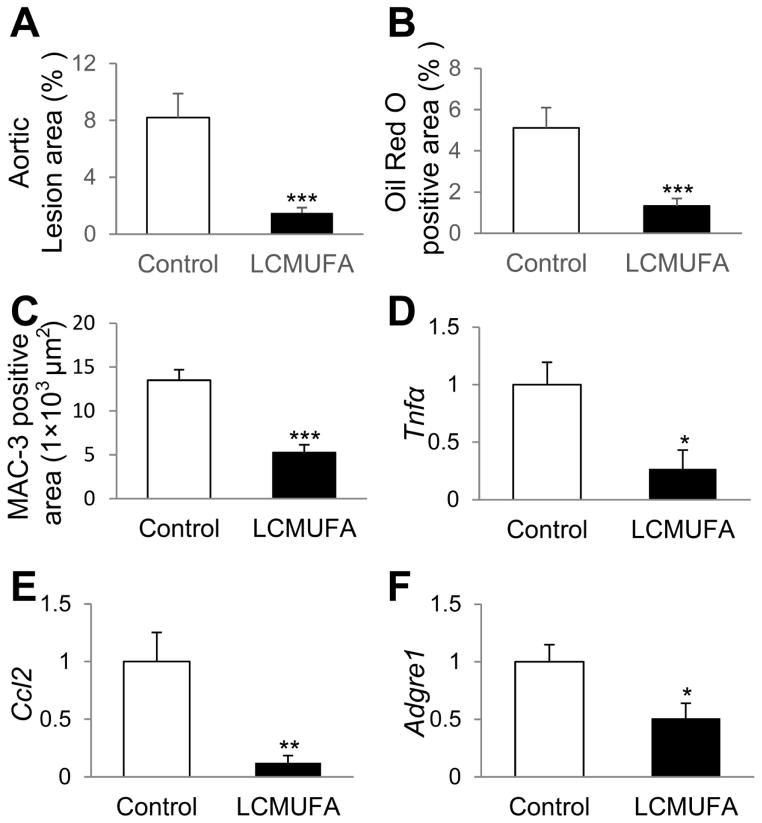

As shown in Fig. 3, the anti-atherosclerotic effect of LCMUFA supplementation was also observed in ApoE-KO mice. 5% LCMUFA significantly (P < 0.05) suppressed the development of atherosclerotic lesions by 81.6% (Fig. 3A, and Supplemental Fig. 2A), and lipid deposition by 74.1% in aortic sinus (Fig. 3B, and Supplemental Fig. 2B). Immunostaining of macrophage marker MAC-2 revealed that LCMUFA diet significantly decreased (P < 0.01) macrophage accumulation in aortic sinus by 40% compared to control (Fig. 3C, and Supplemental Fig. 2C). LCMUFA remarkably (P < 0.05) decreased aortic gene expression of inflammation and macrophage markers, including tumor necrosis factor-alpha (Tnfα) (Fig. 3D), chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2 (Ccl2) (Fig. 3E), and adhesion G protein-coupled receptor E1 (Adgre1) (Fig. 3F).

Figure 3.

Development of atherosclerosis in ApoE-KO mice fed Western diet supplemented with 5% LCMUFA or not (control) for 12 weeks. (A) Quantitative analysis of en face Sudan IV-positive area of aorta (n = 12~16). (B) Quantitative analysis of cross-sectional Oil red O-positive area of aortic sinus (n = 12~15). (C) Quantitative analysis of cross-sectional MAC-2-positive area of aortic sinus (n = 12~15). (D–F) Aortic relative mRNA expression of genes of inflammation and macrophage markers (n = 6~14). (D) Tnfα. (E) Ccl2. (F) Adgre1. Data are shown as mean ± SEM. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. control.

3.4. Plasma inflammatory cytokines

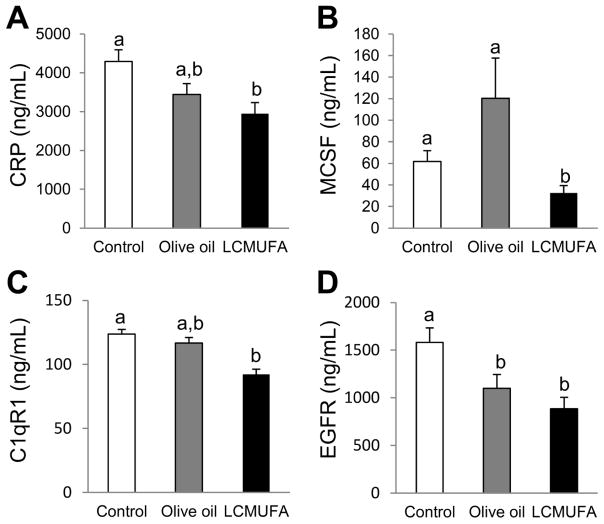

To determine if LCMUFA could attenuate inflammatory markers in LDLR-KO mice, we measured levels of several cytokines in plasma of LDLR-KO mice. 2% LCMUFA, but not olive oil, decreased the plasma concentration of C-reactive protein (CRP), macrophage colony-stimulating factor (MCSF), and Complement component 1q, receptor 1(C1qR1). Compared to control, plasma epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) concentrations were also significantly (P < 0.05) decreased in the olive oil and LCMUFA groups (Fig. 4). Other inflammatory cytokines contained in the multiplex kits were either not significantly different between the three groups or below the limit of detection (Supplemental Table 7).

Figure 4.

Plasma levels of inflammatory cytokines of LDLR-KO mice on a Western diet supplemented with 2% olive oil, LCMUFA, or not (control) for 12 weeks. (A) CRP. (B) MCSF. (C) C1qR1. (D) EGFR. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 12). Labeled means without a common letter differ, P < 0.05.

3.5. Pathway analysis

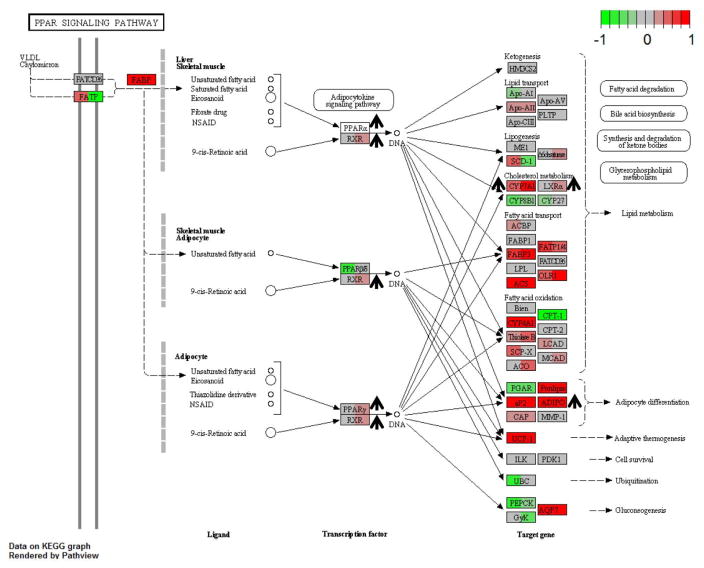

To better understand the anti-atherogenic effect of LCMUFA seen in the LDLR-KO mice without changes in plasma lipoprotein levels, hepatic gene expression was determined by RNA-Seq analysis for mice on the 3 diets. Among the gene sets with False Discovery Rate (FDR) ≥ 0.1, 196 and 45 hepatic genes sets were upregulated due to the LCMUFA diet as compared to the control and olive oil diets, respectively. Supplemental Tables 8 and 9 show the upregulated gene sets involved in atherosclerosis development. There were no downregulated gene sets with FDR ≤ 0.1 after LCMUFA diet compared to the control or olive oil diets. In the LCMUFA-derived upregulated gene sets, the “PPAR signaling pathway” (FDR < 0.01) was among the pathways most affected (Fig. 5). In addition, potential beneficial gene changes on atherosclerosis were also observed in the “Fatty acid degradation pathway” (FDR < 0.01) (Supplemental Fig. 3), in “Primary bile acid biosynthesis” (FDR < 0.01) (Supplemental Fig. 4), and in “Fat digestion and absorption pathway” (FDR = 0.01) (Supplemental Fig. 5) when compared with both control and olive oil diet.

Figure 5.

PPAR signaling pathway upregulated in LCMUFA group compared to control (FDR < 0.01) and olive oil group (FDR < 0.01). LDLR-KO mice were fed a Western diet supplemented with 2% olive oil, LCMUFA, or not (control) for 12 weeks. The nodes represented genes in the pathway. For each node, left panel: gene expression log2(Fold Change) of LCMUFA vs. control; right panel: gene expression log2(Fold Change) of LCMUFA vs. olive oil group (n = 4). Red and green colors of panels in each node indicated up- or down-regulated genes, respectively, by LCMUFA consumption. †: Upregulated genes of interest verified by qPCR.

3.6. Hepatic qPCR analysis

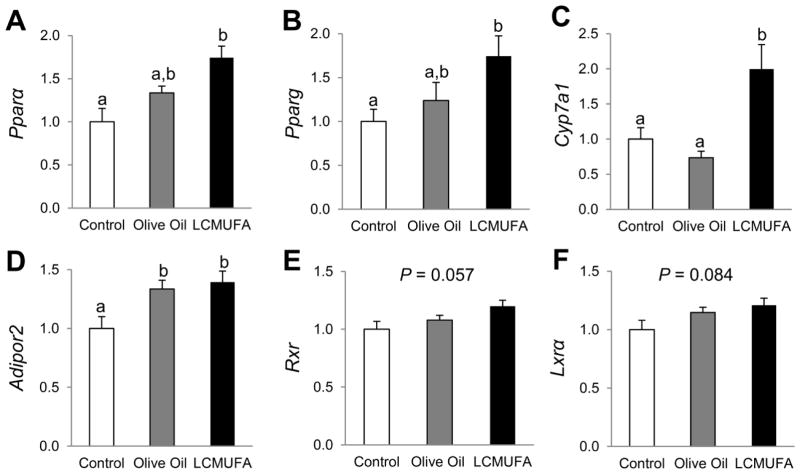

qPCR was used to verify key hepatic gene expression changes in the PPAR signaling pathway in the LDLR-KO mouse study. Similar to what was observed by RNA-Seq analysis, 2% LCMUFA, but not olive oil, enriched diet led to significant increases (P < 0.05) in mRNA expression for Pparα and Pparg (74% and 75% increases, respectively) as compared with the control diet (Figs. 6A and 6B) in LDLR-KO mice. LCMUFA also increased expression of the key bile acid synthase gene Cyp7a1 by 99% (P < 0.05) and 172% (P < 0.05), as compared with the control and olive oil groups, respectively, although there were no significant differences between the control and olive oil groups (Fig. 6C). Compared with the control diet, mRNA expression of Adipor2, which encodes for adiponectin receptor, was also increased by 33% (P < 0.05) in the olive oil group, and by 39% (P < 0.05) in the LCMUFA group (Fig. 6D). Furthermore, the LCMUFA diet tended to increase expression of the nuclear receptor Rxr (retinoid X receptor) (P = 0.057) (Fig. 6E) and Lxrα (Liver X receptor-alpha) (P = 0.084) compared to the control diet (Fig. 6F). Furthermore, in ApoE-KO mice, 5% LCMUFA-supplemented Western diet also increased the mRNA expression of Pparα and Cyp7a1 by 62% and 157%, respectively (Supplemental Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

Hepatic relative mRNA expression of genes involved in PPAR signaling pathway of LDLR-KO mice fed Western diet supplemented with 2% olive oil, LCMUFA, or not (control) for 12 weeks. (A) Pparα. (B) Pparg. (C) Cyp7a1. (D) Adipor2. (E) Rxr. (F) Lxrα. Data are expressed as means ± SEM (n = 12). Labeled means without a common letter differ, P < 0.05.

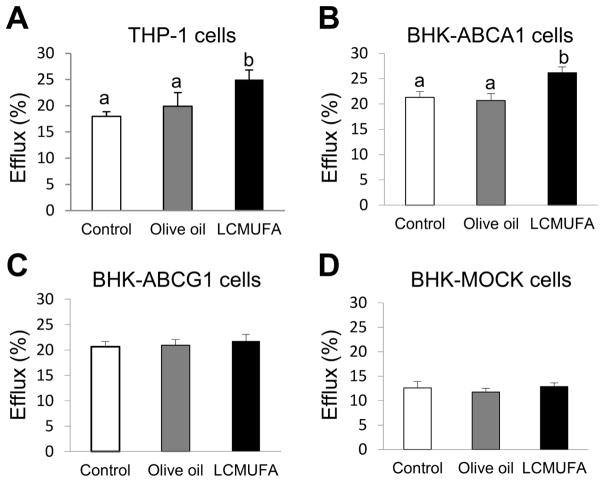

3.7. Cholesterol efflux

We next examined the effect of LCMUFA diet supplementation in LDLR-KO mice on plasma cholesterol efflux from THP-1 macrophage cells. As shown in Fig. 7A, apoB-depleted plasma from the LCMUFA group in LDLR-KO mice, but not the olive oil group, significantly promoted more cholesterol efflux by 39% (P <0.05) compared to control. We then examined the possible pathways for cholesterol efflux by performing the assay in cells stably transfected with either ABCA1 or ABCG1. Plasma from the LCMUFA group, but not the olive oil group, significantly enhanced cholesterol efflux by 25% in BHK-ABCA1 cells (Fig. 7B) compared to control. There were no differences in cholesterol efflux between the three dietary groups from either BHK-ABCG1 (Fig. 7C) or BHK-MOCK cells (Fig. 7D).

Figure 7.

Cholesterol efflux from cultured cells to ApoB-depleted plasma of LDLR-KO mice fed a Western diet supplemented with 2% olive oil, LCMUFA, or not (control) for 12 weeks. (A) Cholesterol efflux from THP-1 cells. (B) Cholesterol efflux from BHK-ABCA1 cells. (C) Cholesterol efflux from BHK-ABCG1 cells. (D) Cholesterol efflux from BHK-MOCK cells. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 5). Labeled means without a common letter differ, P < 0.05.

4. Discussion

This is the first study to demonstrate that supplementation of LCMUFA-rich oil inhibits atherosclerotic plaque formation in two different atherosclerosis mouse models, and is consistent with a previous study in diabetic mice [8] on the beneficial effect of LCMUFA on risk factors for atherosclerosis. The present data also provide evidence that LCMUFA-induced decrease in atherosclerosis is probably the result of combined protective effects of decreasing circulating pro-inflammatory cytokine concentrations and enhancing cholesterol removal from macrophages possibly through stimulation of the PPAR signaling pathway. The observed effects are likely attributed to LCMUFA, which comprised ~60% of the fats in the LCMUFA diet, and LCMUFA-rich diet caused an increase in the hepatic concentration of LCMUFA. The concentration of total saturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids were similar in the three diets and liver in the three groups.

Circulating cholesterol is one of the most important determinants of cardiovascular risk, and reducing LDL-cholesterol has been established as a primary modality for decreasing cardiovascular disease [15]. In our previous mouse study on LCMUFA [8] and in the current study, a higher dose of LCMUFA (4-5% in diet) resulted in significantly decreased plasma total cholesterol or LDL-cholesterol in ApoE-KO mice. A lower dose of LCMUFA (2% w/w), however, did not change plasma cholesterol concentrations in LDLR-KO mice. It is well known that fish oils can have concentration-dependent effect on plasma lipids. Mori et al., for example, reported that no plasma lipid changes were observed when relatively low doses (2% or 4%) of omega-3 PUFA-rich fish oil supplementation (purity of EPA plus DHA: 51%) were included in the diet for 5 months, although an 8% fish oil diet decreased plasma cholesterol significantly compared with high-fat diet group [16]. Nevertheless, LCMUFA suppressed atherosclerosis, and 2% LCMUFA consumption did affect the extent of atherosclerosis without changing the plasma lipid profile in LDLR-KO mice. Besides having less atherosclerotic lesions, mice fed LCMUFA also displayed a more stable plaque morphology characterized by less lipid deposition, decreased accumulation of macrophages and downregulation of marker genes for inflammation and macrophage. Other types of dietary treatments in atherosclerosis mouse models, such as blueberries and sphingolipids, have also been shown to reduce atherosclerosis in mice without significantly affecting serum lipoproteins, and it is well known that statins decrease atherosclerosis in mice without significantly changing plasma lipids [17, 18].

In order to gain insight into the possible anti-atherogenic mechanisms of LCMUFA supplementation, we examined hepatic gene expression changes by RNA-Seq and qPCR analysis of the mice on the three diets. Results from these studies revealed that LCMUFA favorably regulated genes involved in PPAR signaling pathways in both LDLR-KO mice and ApoE-KO mice. PPARs are members of a nuclear hormone receptor superfamily that function in ligand-activated transcription for a large variety of genes involved in atherosclerosis [9]. The PPAR family contains three types of isoforms: α, β/δ, and γ. Activation of PPARα and PPARγ has been demonstrated to be beneficial in cardiovascular disease and protects against atherosclerosis through multiple mechanisms, including regulating lipoprotein metabolism [19]. In the current study, 5% LCMUFA upregulated Pparα mRNA expression and decreased plasma cholesterol, although 2% LCMUFA did not alter plasma cholesterol levels. Accumulated evidence has also shown that PPARα and PPARγ play important roles in inflammation regulation, and their agonists attenuate multiple inflammatory conditions by inhibiting a wide variety of inflammatory pathways [20]. Inflammation plays a fundamental role in mediating all stages of atherosclerosis, and elevated plasma levels of several inflammatory mediators are predictive of future cardiovascular events. For example, elevated CRP levels were associated with atherosclerosis development in observational studies, and baseline CRP levels were shown to predict future cardiovascular events [21]. In the current study, LCMUFA consumption decreased plasma levels of multiple inflammatory cytokines, namely CRP, MCSF, C1qR1, and EGFR in LDLR-KO mice, and the results correlated with the extent of atherosclerosis.

The PPAR target genes Cyp7a1 and Adipor2 were also highly upregulated by LCMUFA in LDLR-KO mice, and in fact were the most highly induced genes in the gene set. Cholesterol-7-alpha hydroxylase (CYP7A1), encoded by Cyp7a1, is the liver-specific enzyme that regulates the rate limiting step in the conversion of cholesterol to bile acids. Transgenic mice overexpressing CYP7A1 were protected from diet-induced atherosclerosis, possibly via the role of CYP7A1 in maintaining hepatic cholesterol and lipoprotein homeostasis [22]. Hepatic Cyp7a1 expression was also increased 1.5-fold by 5% LCMUFA intake in ApoE-KO mice, which possibly contributed to the observed decrease in plasma cholesterol. Adiponectin receptors encoded by Adipor1/r2 have also been shown to play pivotal roles in pleiotropic adiponectin actions, including improving metabolic syndrome and atherosclerosis [23]. Diet-induced obese downregulated hepatic expression of adipor2, the predominant hepatic adiponectin receptor, and impaired adiponectin actions via ADIPOR2 in endothelial cell may cause atherosclerosis, suggesting the importance of this receptor in the maintenance of metabolic homeostasis, as well as improvement of CVD risk. Therefore, upregulation of these two genes by LCMUFA supplementation could also play a role in protecting against atherosclerosis.

PPARs are also known to protect against atherosclerosis by enhancing ABCA1-dependent cholesterol efflux from macrophages in the arterial wall. Cholesterol efflux, in which accumulated cholesterol is removed from macrophages by HDL, is the first and rate-limiting step of the Reverse Cholesterol Transport (RCT) pathway [24]. Synthesized or dietary cholesterol in peripheral tissues is transported from the vessel wall to the liver for either recycling or biliary excretion by the RCT pathway, thus protecting against atherosclerosis. Enhanced cholesterol efflux through activation of the LXR-ABCA1 pathway has been shown to contribute to the protective effect of PPARs on atherosclerosis, and activation of PPARα and PPARγ were previously demonstrated to exert antiatherogenic effects in LDLR-KO mice [20]. Multiple studies have also demonstrated that macrophage-specific RCT contributes to the cardioprotective effect of HDL [25].

Several in vitro studies have previously suggested that unsaturated fatty acids may play a role in the regulation of RCT [26, 27]. In the current study, our results showed that LCMUFA supplementation enhances cholesterol efflux from THP-1-derived macrophages. Several ABC transporter family members, such as ABCA1 and ABCG1, have been shown to promote cholesterol efflux to extracellular acceptors and modulate atherosclerosis [19]. We, therefore, investigated whether LCMUFA supplementation promotes cholesterol efflux through ABC transporters. ApoB-depleted plasma from LDLR-KO mice fed a LCMUFA diet was found to increase cholesterol efflux from BHK-ABCA1 cells, but not from BHK-ABCG1 or BHK-MOCK cells, suggesting a possible role for ABCA1 in increasing cholesterol efflux from mice treated with the LCMUFA diet. As a member of the ABC transporter protein family, ABCA1 is the major transporter that facilitates cholesterol efflux, particularly to small HDL or lipid-poor apoA-I and is the defective gene in Tangier disease patients, who lack ABCA1 activity and accumulate cholesterol in macrophages [19]. In the current study, although individual LCMUFA isomer did not alter cholesterol efflux rate in cell culture study (Supplemental Fig. 7), LCMUFA-rich diet improved the rate of cholesterol efflux possibly via ABCA1 through upregulation of PPARs without altering plasma HDL levels in LDL-KO mice. Lesna et al. reported that a decrease in plasma HDL cholesterol levels did not result in a decrease in cholesterol efflux after replacing dietary saturated FA with PUFA in healthy subjects, suggesting that the level of circulating HDL does not completely correspond to the kinetics of RCT and may be more related to HDL function [28]. By using a validated ex vivo system that incubated macrophages with apoB-depleted serum from the study participants, recent clinical study has also demonstrated a negative correlation between in vitro cholesterol efflux from macrophages and carotid atherosclerosis independently of HDL cholesterol mass [29]. Nevertheless, more studies are needed to investigate the effect of LCMUFA metabolites on cholesterol efflux, as well as the effect of LCMUFA on the composition and/or structure of HDL.

In conclusion, although a lower dose (2%, w/w) of LCMUFA did not alter plasma lipids, dietary supplementation of LCMUFA decreased atherosclerosis in both LDLR-KO mice and ApoE-KO mice. The LCMUFA diet upregulated hepatic mRNA expression of key genes in the PPAR signaling pathway, which could account for the some of the observed beneficial changes in inflammation and cholesterol efflux. Further studies are needed to elucidate the potential regulatory effects of individual LCMUFA isomers on modulating PPAR levels, as well as the effects of different doses of LCMUFA on lipoprotein levels in different mouse models. Given the promising results from this study and the fact that fish oils are the most commonly used dietary supplement, more human studies on the effect of LCMUFA and some of the other minor fatty acid components in fish oils are needed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Conceived and designed the experiments: Z.-H.Y., H.S., M. S. and A.R. Performed the experiments: Z.-H.Y., M.B., T.S., B.E.-O., B.W., D.F., B.V., M.P., Y.W, M.S., Z.-X. Y., A.S. and A.Z. Analyzed the data: Z.-H.Y., M.B., T.S., Y.C., A.S. Wrote the manuscript: Z.-H.Y. and A.R.

We wish to thank Tadaomi Naka and Yuji Hirouchi for technical assistance and Lita Freeman for her help with the preparation of the manuscript. This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and the Office of Dietary Supplements (ODS) Research Scholars Program at National Institutes of Health.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- FA

fatty acids

- FC

free cholesterol

- KO

knockout

- LCMUFA

long-chain monounsaturated fatty acids

- MUFA

monounsaturated fatty acids

- PL

phospholipid

- PUFA

polyunsaturated fatty acids

- TC

total cholesterol

- TG

triglyceride

References

- 1.Libby P, Ridker PM, Hansson GK. Progress and challenges in translating the biology of atherosclerosis. Nature. 2011;473:317–325. doi: 10.1038/nature10146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Calder PC, Yaqoob P. Understanding omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Postgrad Med. 2009;121:148–157. doi: 10.3810/pgm.2009.11.2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang ZH, Miyahara H, Takemura S, Hatanaka A. Dietary saury oil reduces hyperglycemia and hyperlipidemia in diabetic KKAy mice and in diet-induced obese C57BL/6J mice by altering gene expression. Lipids. 2011;46:425–434. doi: 10.1007/s11745-011-3553-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang ZH, Miyahara H, Takeo J, Hatanaka A, Katayama M. Pollock oil supplementation modulates hyperlipidemia and ameliorates hepatic steatosis in mice fed a high-fat diet. Lipids Health Dis. 2011;10:189. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-10-189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dyerberg J, Bang HO, Stoffersen E, Moncada S, Vane JR. Eicosapentaenoic acid and prevention of thrombosis and atherosclerosis? Lancet. 1978;2:117–119. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(78)91505-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bang HO, Dyerberg J, Sinclair HM. The composition of the Eskimo food in north Western Greenland. Am J Clin Nutr. 1980;33:2657–2661. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/33.12.2657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsumoto C, Matthan NR, Lichtenstein AH, Gaziano JM, Djoussé L. Red blood cell MUFAs and risk of coronary artery disease in the Physicians' Health Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;98:749–754. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.059964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang ZH, Miyahara H, Iwasaki Y, Takeo J, Katayama M. Dietary supplementation with long-chain monounsaturated fatty acids attenuates obesity-related metabolic dysfunction and increases expression of PPAR gamma in adipose tissue in type 2 diabetic KK-Ay mice. Nutr Metab. 2013;10:16. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-10-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bensinger SJ, Tontonoz P. Integration of metabolism and inflammation by lipid-activated nuclear receptors. Nature. 2008;454:470–477. doi: 10.1038/nature07202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silva S, Combet E, Figueira ME, Koeck T, Mullen W, Bronze MR. New perspectives on bioactivity of olive oil: evidence from animal models, human interventions and the use of urinary proteomic biomarkers. Proc Nutr Soc. 2015;74:268–281. doi: 10.1017/S0029665115002323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zadelaar S, Kleemann R, Verschuren L, de Vries-Van der Weij J, et al. Mouse models for atherosclerosis and pharmaceutical modifiers. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:1706–1721. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.142570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vaisman BL, Klein HG, Rouis M, Berard AM, et al. Overexpression of human lecithin cholesterol acyltransferase leads to hyperalphalipoproteinemia in transgenic mice. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:12269–12275. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.20.12269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vaughan AM, Oram JF. ABCA1 redistributes membrane cholesterol independent of apolipoprotein interactions. J Lipid Res. 2003;44:1373–1380. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M300078-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.VanderLaan PA, Reardon CA, Getz GS. Site specificity of atherosclerosis: site-selective responses to atherosclerotic modulators. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:12–22. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000105054.43931.f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baigent C, Keech A, Kearney PM, Blackwell L, et al. Efficacy and safety of cholesterol-lowering treatment: prospective meta-analysis of data from 90,056 participants in 14 randomised trials of statins. Lancet. 2005;366:1267–1278. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67394-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mori T, Kondo H, Hase T, Tokimitsu I, Murase T. Dietary fish oil upregulates intestinal lipid metabolism and reduces body weight gain in C57BL/6J mice. J Nutr. 2007;137:2629–2634. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.12.2629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu X, Kang J, Xie C, Burris R, et al. Dietary blueberries attenuate atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice by upregulating antioxidant enzyme expression. J Nutr. 2010;140:1628–1632. doi: 10.3945/jn.110.123927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hojjati MR, Li Z, Zhou H, Tang S, et al. Effect of myriocin on plasma sphingolipid metabolism and atherosclerosis in apoE-deficient mice. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:10284–10289. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412348200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chinetti G, Lestavel S, Bocher V, Remaley AT, et al. PPAR-alpha and PPAR-gamma activators induce cholesterol removal from human macrophage foam cells through stimulation of the ABCA1 pathway. Nat Med. 2001;7:53–58. doi: 10.1038/83348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moraes LA, Pigueras L, Bishop-Bailey D. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors and inflammation. Pharmacol Ther. 2006;110:371–385. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ridker PM. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein: potential adjunct for global risk assessment in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2001;103:1813–1818. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.13.1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miyake JH, Duong-Polk XT, Taylor JM, Du EZ, et al. Transgenic expression of cholesterol-7-alpha-hydroxylase prevents atherosclerosis in C57BL/6J mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:121–126. doi: 10.1161/hq0102.102588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hui X, Lam KS, Vanhoutte PM, Xu A. Adiponectin and cardiovascular health: an update. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;165:574–590. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01395.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rader DJ, Pure E. Lipoproteins, macrophage function, and atherosclerosis: beyond the foam cell? Cell Metab. 2005;1:223–230. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cuchel M, Rader DJ. Macrophage reverse cholesterol transport: key to the regression of atherosclerosis? Circulation. 2006;113:2548–2555. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.475715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shao F, Ford DA. Differential regulation of ABCA1 and macrophage cholesterol efflux by elaidic and oleic acids. Lipids. 2013;48:757–767. doi: 10.1007/s11745-013-3808-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Y, Oram JF. Unsaturated FA inhibit cholesterol efflux from macrophages by increasing degradation of ATP-binding cassette transporter A1. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:5692–5697. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109977200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lesna IK, Suchanek P, Kovar J, Stavek P, Poledne R. Replacement of dietary saturated FAs by PUFAs in diet and reverse cholesterol transport. J Lipid Res. 2008;49:2414–2418. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M800271-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khera AV, Cuchel M, de la Llera-Moya M, Rodrigues A, et al. Cholesterol efflux capacity, high-density lipoprotein function, and atherosclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:127–135. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.