Critical illness polyneuromyopathy (CIPNM) usually presents clinically as symmetric weakness in someone who is critically ill

Flaccid weakness develops in the limbs or respiratory muscles; the latter may present as difficulty in weaning from ventilation. Sensation may be reduced to pinprick. Reflexes may be present in the acute phase of the illness but are generally reduced or absent. Cranial nerve and autonomic function is usually preserved. Imaging and the results of cerebrospinal fluid analysis are normal.1 Creatine kinase levels are typically normal or mildly elevated.2

Primary risk factors are markers of increased critical illness severity

CIPNM affects 25%–45% of people with critical illness and up to 100% of those with multiorgan failure.2 The pathophysiology is complex and likely multifactorial (Figure 1).3 Established risk factors include duration of sepsis, number of organ systems involved and immobility.2 Other contributory factors may include neuromuscular blocking agents, glucocorticoids, aminoglycoside antibiotics and hyperglycemia.2

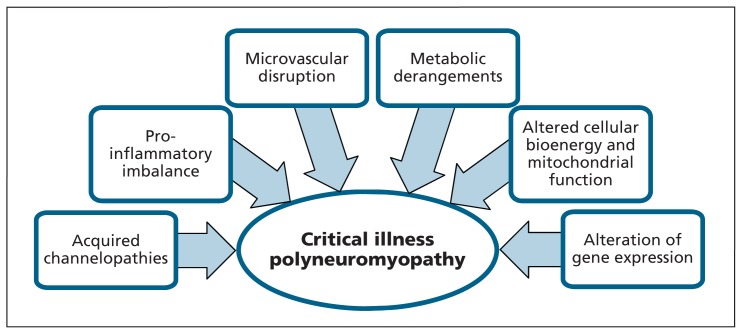

Figure 1:

Critical illness polyneuromyopathy involves multiple pathophysiologic mechanisms,3 as shown here.

Diagnosis requires nerve conduction studies and electromyography

The diagnosis is based on a history of critical illness, evidence of limb or respiratory weakness, and results of electrodiagnostic testing consistent with axonal motor and sensory polyneuropathy or myopathy (or both) that is not explained by another cause.1

CIPNM can cause persistent functional limitations

CIPNM is associated with increased length of stay in the intensive care unit, prolonged mechanical ventilation and greater mortality.2 Those with myopathy alone have a better prognosis. Those with neuropathy have delayed recovery, with over one-third of individuals showing substantial functional limitations at one year.4

Management is focused on prevention and rehabilitation

There is moderate-quality evidence that intensive insulin therapy and early physical therapy reduce the incidence and effects of CIPNM.5 Avoidance of risk factors such as corticosteroids and neuromuscular blocking agents, unless essential, is advised. We suggest early consultation with a physical medicine and rehabilitation specialist to help identify the disorder, prevent complications and initiate rehabilitation interventions such as exercise and bracing.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Bolton CF. Neuromuscular manifestations of critical illness. Muscle Nerve 2005;32:140–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lacomis D. Neuromuscular disorders in critically ill patients: review and update. J Clin Neuromuscul Dis 2011;12:197–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friedrich O, Reid MB, Van den Berghe G, et al. The sick and the weak: neuropathies/myopathies in the critically ill. Physiol Rev 2015;95:1025–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koch S, Wollersheim T, Bierbrauer J, et al. Long-term recovery in critical illness myopathy is complete, contrary to polyneuropathy. Muscle Nerve 2014;50:431–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hermans G, De Jonghe B, Bruyninckx F, et al. Interventions for preventing critical illness polyneuropathy and critical illness myopathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;(1):CD006832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]