Abstract

The influenza A (H1N1) virus, also known as swine flu is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality since 2009. There is a need to explore novel anti-viral drugs for overcoming the epidemics. Traditionally, different plant extracts of garlic, ginger, kalmegh, ajwain, green tea, turmeric, menthe, tulsi, etc. have been used as hopeful source of prevention and treatment of human influenza. The H1N1 virus contains an important glycoprotein, known as neuraminidase (NA) that is mainly responsible for initiation of viral infection and is essential for the life cycle of H1N1. It is responsible for sialic acid cleavage from glycans of the infected cell. We employed amino acid sequence of H1N1 NA to predict the tertiary structure using Phyre2 server and validated using ProCheck, ProSA, ProQ, and ERRAT server. Further, the modelled structure was docked with thirteen natural compounds of plant origin using AutoDock4.2. Most of the natural compounds showed effective inhibitory activity against H1N1 NA in binding condition. This study also highlights interaction of these natural inhibitors with amino residues of NA protein. Furthermore, among 13 natural compounds, theaflavin, found in green tea, was observed to inhibit H1N1 NA proteins strongly supported by lowest docking energy. Hence, it may be of interest to consider theaflavin for further in vitro and in vivo evaluation.

Keywords: influenza A Virus, molecular docking analysis, neuraminidase, phytochemicals

Introduction

Swine flu, also known as influenza A (H1N1) is an infectious disease caused by RNA viruses of the family Orthomyxoviridae [1]. The H1N1 influenza virus arises due to the genetic recombination of genes from pig, human, and bird's H1N1 virus. It is unevenly spherical and is enveloped by a lipid membrane containing two glycoproteins namely hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA) [1], which are responsible for viral infection [2]. HA helps in attachment of the viral strain on the host cell surface and is needed for infection, while NA is responsible initiation of viral infection by cleaving of sialic acid from glycans of the infected cell [3,4]. As these two glycoproteins are very essential for viral infection, these can be considered as excellent drug targets for the control of viral influenza, including H1N1. Although oseltamivir and zanamivir, two NA inhibitors approved for treatment and prevention of influenza [5,6], more effective natural medications are required for preventing the wide spread of swine flu.

There are many plant products traditionally used for treatment of common cold that provide relief from symptoms, including sore throat, sneezing, nasal congestion and blocked nose [7]. Most of them are plant extracts and the exact mechanism of action are yet to be fully understood. The interaction profile of the active compounds of those plant extracts with viral proteins are need to be explored further, so as to design novel drugs of natural origin which could be possibly used effectively in prevention or treatment of H1N1 influenza without any adverse effects.

There are many plant products traditionally used for treatment of influenza infection among them few natural compounds such as allicin, ajoene, andrographolide, baicalin, carvacrol, catechin, coumarin, curcumin, menthol, eugenol, theaflavin, ursolic acid, and tinosporon have been reported to act against human influenza. The active constituents of the essential oil from the fruit of Trachyspermum ammi are thymol and carvacrol [8]. The essential oil has strong antiseptic, antispasmodic, aromatic, bitter, diaphoretic, digestive, diuretic, expectorant, and tonic [9]. Also, it is used for the treatment of cold, cough, influenza, and asthma [10]. The Ocimum sanctum have great Ayurvedic treatment option for swine flu. The main chemical constituents of O. sanctum are oleanolic acid, ursolic acid, rosmarinic acid, eugenol, carvacrol, linalool, and β-caryophyllene [11]. The antimicrobial properties of O. sanctum make it useful for the prevention of novel H1N1 flu. Basil is safe, with no side effects and is great to prevent swine flu from spreading like wildfire [12]. Zingiber officinalis (ginger) has been reported as the natural remedies for swine flu prevention. The active compounds present in ginger are allicin, alliin, and ajoene etc and the compound allicin has been reported to have anti-influenza cytokine [13]. Allium sativum (garlic) has natural antiviral, antibacterial, and immune-boosting properties and has been used for hundreds of years to treat fungal, parasitic, and viral infections, and has anti-inflammatory properties and it is reported to kill influenza virus in vitro condition [14]. The active compound found in fresh garlic is ajoene. Curcumin, the active constituents of Curcuma longa (turmeric), is reported to have strong antioxidant with antiinflammatory, anti-viral properties [15]. Tinospora cordifolia having active compound tinosporon, tinosporic acid, and syringen prevent swine flu. The plant has immense potential for use against novel H1N1 flu since it is a potent immunostimulant [16]. The principal components of the oil of Mentha piperita are menthol (29%), menthone (20% to 30%), and menthyl acetate (3% to 10%). Menthol has antimicrobial and antiviral activity and also observed to have virucidal against influenza, herpes, and other viruses in vitro [17]. Green tea is particularly rich in polyphenolic compounds like theaflavin and catechins. Catechin and theaflavin derivatives have shown pronounced antiviral activity. Green tea has the ability to enhance humoral and cell-mediated immunity and therefore, useful for preventing influenza by inhibiting flu replication using potentially directs virucidal effect [7,18].

In the current study, we performed docking analysis to explore the atomic interaction and molecular mechanism between 13 plants originated active compounds such as allicin, ajoene, andrographolide, baicalin, carvacrol, catechin, coumarin, curcumin, menthol, eugenol, theaflavin, tinosporon, and ursolic acid against NA protein of H1N1. This study comprises of protein structure modeling of NA using Phyre2 server followed by structural refinement and energy minimization by Yet Another Scientific Artificial Reality Application (YASARA) energy minimization server. Auto-Dock4.2 tool was used to analyze the molecular interaction between NA with natural ligands.

Methods

Neuraminidase of H1N1

NA protein of H1N1 was selected as the drug target. The protein sequence of H1N1 NA (ID: ADJ40637.1) was retrieved from NCBI (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/).

Molecular modelling and structural validation of drug target

Phyre2 server was used for modeling of the tertiary structure of NA protein. It predict the three-dimensional (3D) structure of a protein sequence using the principles and techniques of homology modeling. Because the structure of a protein is more conserved in evolution than its amino acid sequence, a protein sequence of interest (the target) can be modeled with reasonable accuracy on a very distantly related sequence of known structure (the template), provided that the relationship between target and template can be discerned through sequence alignment [19]. YASARA Energy Minimization Server [20] was employed for structural refinement and energy minimization of the predicted model. The refined model reliability was evaluated through ProCheck [21], ProSA-web [22], ProQ [23], and ERRAT server [24].

Ligand preparation and molecular docking

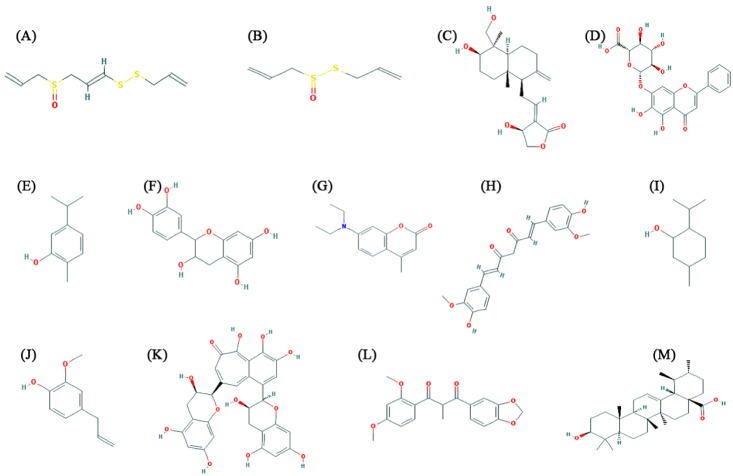

Chemical structures of 13 natural compounds (allicin, ajoene, andrographolide, baicalin, carvacrol, catechin, coumarin, curcumin, menthol, eugenol, theaflavin, tinosporon, and ursolic acid) (Fig. 1), along with Chemical Abstracts Service registry numbers, reported in the literature were retrieved from the PubChem database (Table 1) [25]. Both ligands and receptor molecule (H1N1 NA) was prepared in AutoDock4.2 program [26]. AutoDock is used to predict small molecule to the receptors of known 3D structure. The ligand and target protein were given as input and the flexible docking was performed. The negative and low value of ΔG bind indicates strong favorable bonds between protein and the novel ligand indicating that the ligand was in its most favorable conformations [26]. Docking studies were carried out as per the normal methodology for protein-ligand docking used by Kumar et al. [27] and Jagadeb et al. [28].

Fig. 1. Chemical structures of natural compounds. (A) Ajoene. (B) Allicin. (C) Andrographolide. (D) Baicalin. (E) Carvacrol. (F) Catechin. (G) Coumarin. (H) Curcumin. (I) Menthol. (J) Eugenol. (K) Theaflavin. (L) Tinosporon. (M) Ursolic acid.

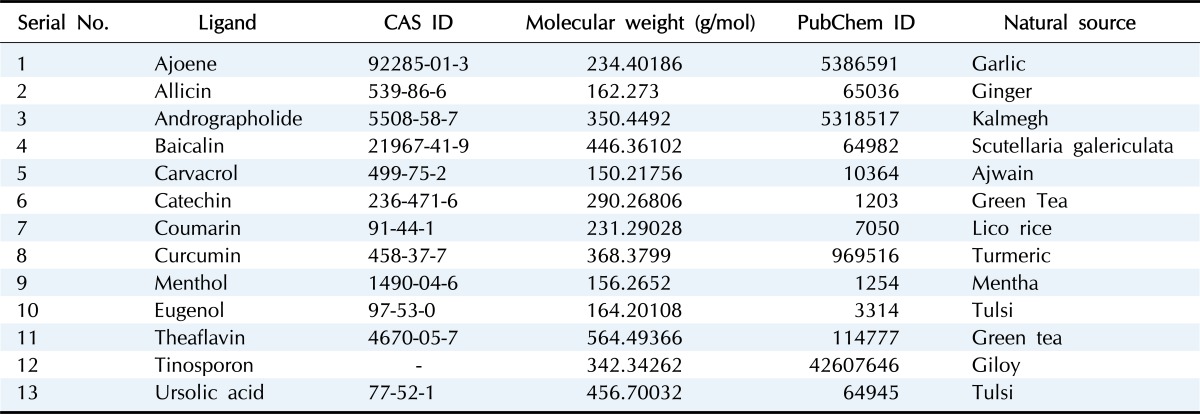

Table 1. Natural compounds reported to use against influenza.

CAS, Chemical Abstracts Service.

Visualization

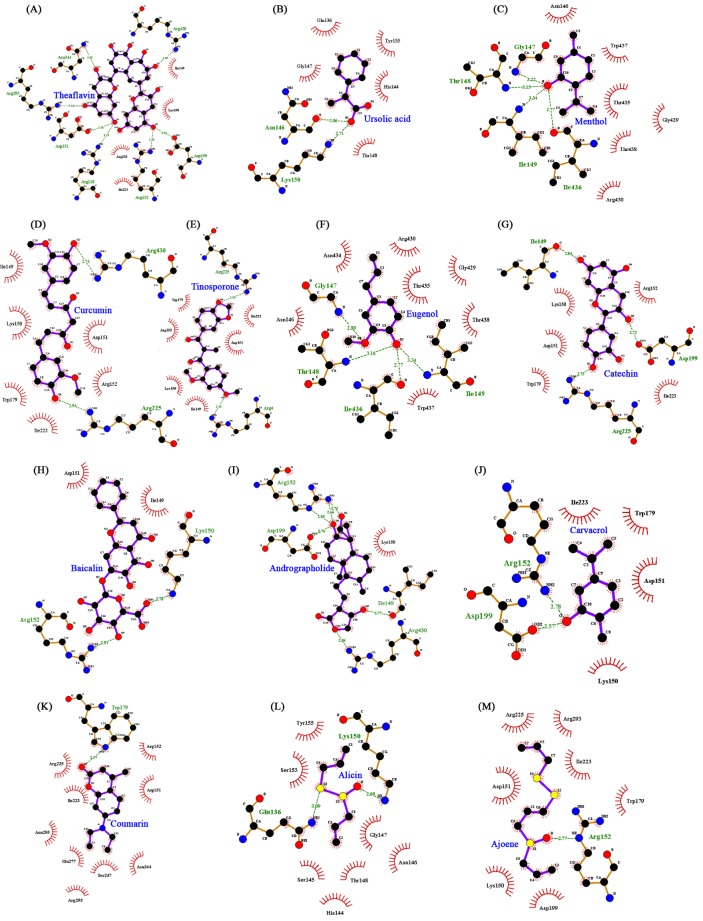

The visualization of structure files was done using the graphical interface of the ADT tool and the schematic diagrams of protein-ligand interactions was prepared using the LigPlot [29].

Results and Discussion

Structural model and evaluation of NA receptor

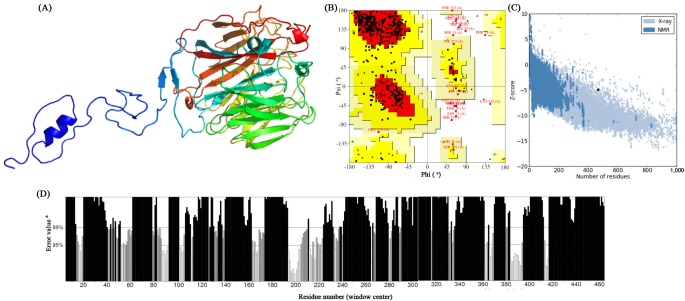

NA protein of H1N1 is of length of 469 amino acids sequence. Due to unavailability of experimentally determined structure of selected NA protein, tertiary structure was predicted using the Phyre2 web server. Two templates were used to predict the 3D structures of NA protein (Fig. 2A), such as D chain of H5N1 NA in complex with oseltamivir (Protein Data Bank [PDB] ID: 2HU4) [30] and D chain of I223R NA mutant structure (PDB ID: 4B7Q) [31]. The predicted structure was then subjected to the YASARA Energy Minimization Server for structural refinement. The total energy for the refined structure obtained from the YASARA Energy Minimization Server for NA was –194,023.8 kJ/mol (score, –2.68) where prior to energy minimization, it was 25,622,682,021,439 kJ/mol (score, –7.17). The stereochemistry of the refined model of NA (ProCheck analysis) (Fig. 2B) revealed that 94.4% residues were situated in the most favorable region and additional allowed regions and 1.8% of residues were in the generously allowed region, whereas 3.8% the residues fell in the disallowed region of the Ramachandran plot (Fig. 2B). ProSA-web evaluation revealed a compatible Z score value of NA was obtained to be –4.89 (Fig. 2C) which is well within the range of native conformations of crystal structures. The overall residual energies of the NA tertiary model were largely negative except for few peaks. The 3D model of H1N1 NA protein showed a Levitt-Gerstein (LG) score of 4.183 and Maxus 0.060 by Protein Quality Predictor (ProQ) tool, implying a high accuracy level of the predicted structure. A ProQ LG score > 2.5 is necessary for suggesting that a model is of very good quality [24]. Similar assumptions were achieved using the ERRAT plot where the overall quality factor for NA was observed to be 13.015 (Fig. 2D). All of these outcomes recommended the reliability of the proposed model.

Fig. 2. (A) Predicted protein structure of neuraminidase (NA). (B) Ramachandran plot of predicted NA model (the red, dark yellow, and light yellow regions represent the most favored, allowed, and generously allowed regions). (C) ProSA-web Z-scores of NA (all protein chains in Protein Data Bank [PDB] determined by X-ray crystallography [light blue] and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy [dark blue] with respect to their length). (D) ERRAT plot of NA for residue-wise analysis of homology model. NMR, nuclear magnetic resonance. aOn the error axis, two lines are drawn to indicate the confidence with which it is possible to reject regions that exceed that error value.

Docking analysis of H1N1 NA with natural ligands

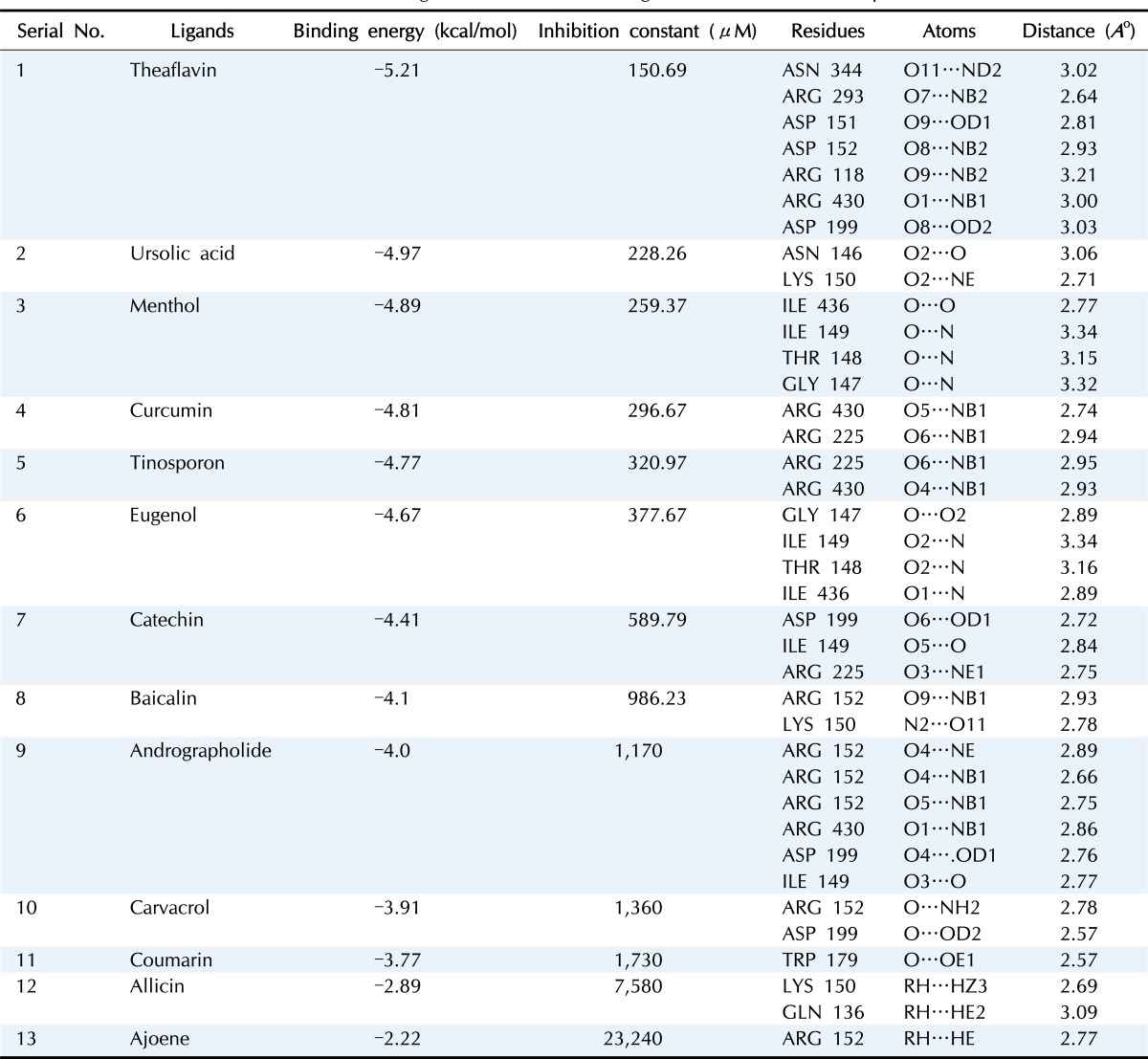

Few earlier in silico docking studies conducted against NA protein with zanamivir, oseltamivir and some natural ligands to recommend NA as a suitable drug target as well as the importance of natural inhibitors [32,33]. In this study, we have predicted the structure of NA for docking analysis and found that all natural ligands (inhibitors) were docked in various conformations and with varying binding energies, the lowest energy conformation was selected. Upon docking, the high-ranked binding energies of modeled structures of NA (Table 2) proteins with natural ligands were obtained. All the 13 active natural compounds were found to interact with the receptor at the sialic acid site (Fig. 3A–M). In our docking study, among the 13 different ligands, theaflavin showed the lowest binding energy (–5.21 kcal/mol) and inhibition constant (150.69 µM) for the protein (H1N1 NA)-ligand complex. Theaflavin was found to interact with the amino acid residues like Arg118, Asp151, Asp 152, Arg193, Asp199, Asn344, and Arg430 of NA by forming hydrogen bonds (Fig. 3A). Theaflavin and catechins are two active polyphenolic compounds found in green tea and reported to have pronounced antiviral activity [7,18]. Due to its ability to enhance humoral and cell-mediated immunity, green tea is very useful for preventing influenza by inhibiting flu replication. Further, ursolic acid showed the second lowest binding energy of –4.97 kcal/mol and an inhibition constant of 228.26 µM. During docking with the receptor it formed two hydrogen bond with Asn146 and Lys150 of NA (Fig. 3B). Ursolic acid is the active component of O. sanctum (tulsi) which has great ayurvedic treatment option for swine flu and due to its antimicrobial properties it useful for the prevention of novel H1N1 flu [17]. The principal components of the oil of M. piperita are menthol (29%), menthone (20% to 30%), and menthyl acetate (3% to 10%). Menthol has antimicrobial and antiviral activity and also observed to have virucidal against influenza, herpes, and other viruses in vitro [11]. In our docking study, the interaction binding energy of menthol and NA was observed to be –4.89 kcal/mol with inhibition constant of 259.37 µM. Further, it formed four hydrogen bonds with amino acid residues (Ile436, Ile149, Thr148, and Gly147) of NA (Fig. 3C).

Table 2. Polar contact information from docking calculations between ligands and neuraminidase protein.

Fig. 3. Interaction profile of all 13 natural ligands with neuraminidase showing interaction of ligands with the active site residues of receptors by forming hydrogen bonds drawn by LigPlot. (A) Theaflavin. (B) Ursolic acid. (C) Menthol. (D) Curcumin. (E) Tinosporone. (F) Eugenol. (G) Catechin. (H) Baicalin. (I) Andrographolide. (J) Carvacrol. (K) Coumarin. (L) Alicin. (M) Ajoene.

Further, other natural compounds like curcumin, reported to have strong antioxidant with anti-inflammatory, anti-viral properties [15]; carvacrol, the active constituent of the essential oil from the fruit of Trachyspermum ammi [8] which is used for the treatment of colds, coughs, influenza, and asthma [10]; allicin (active compounds present in ginger) has been reported to have anti-influenza cytokine [13]; ajoene present in garlic and the garlic has been used for hundreds of years to treat fungal, parasitic, and viral infections, and has anti-inflammatory properties and it is reported to kill influenza virus in vitro [14]. Further, curcumin, tinosporon, eugenol, catechin, baicalin, and andrographolide were also found to inhibit H1N1 NA with significant binding energy of in the range of –4.89 to –4.0 kcal/mol (Table 2). The current in silico docking study, also observed all these natural ligands inhibits H1N1 NA with significant binding energy (Table 2).

All natural ligands were reported to block influenza infection; our docking study also revealed the in silico validation for the possible mechanism of blocking. Most of the natural ligands were found to interact with H1N1 NA protein with effective binding energy and with amino acid residues known for sialic acid binding. This interaction might prevent NA glycoprotein from interacting with host sialic acid, which may correlate with why these natural compounds are used to prevent or treat against influenza without any adverse effect.

All natural ligands were reported to block influenza infection; our docking study also revealed the in silico validation for the possible mechanism of blocking. Most of the natural ligands were found to interact with H1N1 NA protein with effective binding energy and with amino acid residues known for sialic acid binding. This interaction might prevent NA glycoprotein from interacting with host sialic acid, which may correlate with why these natural compounds are used to prevent or treat against influenza without any adverse effect.

In conclusion, different natural/herbal products with antiviral activity have been traditionally used to prevent or reduce the effects of the viral infection. Most of literature has given stress on using natural products of plant origin. It is the time for in silico validation of those plant products against viral proteins before in vitro and in vivo study. The major antigenic determinants of H1N1 virus is NA which is a surface glycoprotein and is a suitable target for H1N1. Thus, in order to prevent or cure viral infection, there is need to identify new inhibitors against NA. The in silico docking approaches used in this study revealed the molecular interaction of natural ligands against NA protein which may be of interest in designing new drugs from natural sources against H1N1. Out of all the inhibitors molecules, Theaflavin has been docked with minimum binding energy of –5.21 kcal/mol by forming hydrogen bonding with amino acid residue of the receptor can be consider for in vitro and in vivo validation.

Acknowledgments

Authors express gratitude to the Department of Biotechnology, MoS&T, Government of India for supporting Bioinformatics Centre wherein this study has been carried out. Grateful thanks to Shri D.S. Mehta, President, Kasturba Health Society; Dr. B.S. Garg, Secretary, Kasturba Health Society; Dr. K.R. Patond, Dean, MGIMS; Dr. S.P. Kalantri, Medical Superintendent, Kasturba Hospital, MGIMS, Sevagram and Dr. B.C. Harinath, Director, JBTDRC & Coordinator, Bioinformatics Centre for their encouragement.

References

- 1.Behera DK, Behera PM, Acharya L, Dixit A, Padhi P. In silico biology of H1N1: molecular modelling of novel receptors and docking studies of inhibitors to reveal new insight in flu treatment. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2012;2012:714623. doi: 10.1155/2012/714623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gallaher WR. Towards a sane and rational approach to management of Influenza H1N1 2009. Virol J. 2009;6:51. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-6-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harrison SC. Viral membrane fusion. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:690–698. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burmeister WP, Ruigrok RW, Cusack S. The 2.2 A resolution crystal structure of influenza B neuraminidase and its complex with sialic acid. EMBO J. 1992;11:49–56. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05026.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eiland LS, Eiland EH. Zanamivir for the prevention of influenza in adults and children age 5 years and older. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2007;3:461–465. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heinonen S, Silvennoinen H, Lehtinen P, Vainionpää R, Vahlberg T, Ziegler T, et al. Early oseltamivir treatment of influenza in children 1-3 years of age: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:887–894. doi: 10.1086/656408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Narayanan MM, Nair CB, Sanjeeva SK, Rao PS, Pullela PK, Barrow CJ. Design of multiligand inhibitors for the swine flu H1N1 neuraminidase binding site. Adv Appl Bioinform Chem. 2013;6:47–53. doi: 10.2147/AABC.S49503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arora R, Singh S, Sharma RK. Neem leaves: Indian herval medicine. In: Watson RR, Preedy VR, editors. Botanical Medicine in Clinical Practice. Wallingford: CABI; 2008. pp. 85–98. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chatterjee A, Saha SK. Isolation of allo-imperatorin and β-sitosterol from the fruits of Aegle marmelos Correa. J Indian Chem Soc. 1957;34:228–230. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spickler AR. Influenza. Ames: The Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University; 2014. [Accessed 2015 May 17]. Available from: http://www.cfsph.iastate.edu/Factsheets/pdfs/influenza.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shah A, Krishnamurthy R. Swine flu and its herbal remedies. Int J Eng Sci. 2013;2:68–78. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chopra RN, Nayar SL, Chopra IC. Glossary of Indian Medicinal Plants. New Delhi: Council of Scientific & Industrial Research; 1956. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hornung B, Amtmann E, Sauer G. Lauric acid inhibits the maturation of vesicular stomatitis virus. J Gen Virol. 1994;75(Pt 2):353–361. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-2-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wolkerstorfer A, Kurz H, Bachhofner N, Szolar OH. Glycyrrhizin inhibits influenza A virus uptake into the cell. Antiviral Res. 2009;83:171–178. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Winston D, Maimes S. Adaptogens: Herbs for Strength, Stamina, and Stress Relief. Rochester: Healing Arts Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bown D. Encyclopedia of Herbs and Their Uses. London: Dorling Kindersley; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Naik GH, Priyadarsini KI, Naik DB, Gangabhagirathi R, Mohan H. Studies on the aqueous extract of Terminalia chebula as a potent antioxidant and a probable radioprotector. Phytomedicine. 2004;11:530–538. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yiannakopoulou EC. Recent patents on antibacterial, antifungal and antiviral properties of tea. Recent Pat Antiinfect Drug Discov. 2012;7:60–65. doi: 10.2174/157489112799829738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kelley LA, Sternberg MJ. Protein structure prediction on the Web: a case study using the Phyre server. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:363–371. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krieger E, Joo K, Lee J, Lee J, Raman S, Thompson J, et al. Improving physical realism, stereochemistry, and side-chain accuracy in homology modeling: Four approaches that performed well in CASP8. Proteins. 2009;77(Suppl 9):114–122. doi: 10.1002/prot.22570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laskowski RA, MacArthur MW, Moss DS, Thornton JM. PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J Appl Cryst. 1993;26:283–291. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wiederstein M, Sippl MJ. ProSA-web: interactive web service for the recognition of errors in three-dimensional structures of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:W407–W410. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wallner B, Elofsson A. Can correct protein models be identified? Protein Sci. 2003;12:1073–1086. doi: 10.1110/ps.0236803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Colovos C, Yeates TO. Verification of protein structures: patterns of nonbonded atomic interactions. Protein Sci. 1993;2:1511–1519. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560020916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Y, Xiao J, Suzek TO, Zhang J, Wang J, Bryant SH. PubChem: a public information system for analyzing bioactivities of small molecules. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:W623–W633. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morris GM, Huey R, Lindstrom W, Sanner MF, Belew RK, Goodsell DS, et al. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J Comput Chem. 2009;30:2785–2791. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kumar S, Jena L, Galande S, Daf S, Mohod K, Varma AK. Elucidating molecular interactions of natural inhibitors with HPV-16 E6 oncoprotein through docking analysis. Genomics Inform. 2014;12:64–70. doi: 10.5808/GI.2014.12.2.64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jagadeb M, Konkimalla VB, Rath SN, Das RP. Elucidation of the inhibitory effect of phytochemicals with Kir6.2 wild-type and mutant models associated in Type-1 diabetes through molecular docking approach. Genomics Inform. 2014;12:283–288. doi: 10.5808/GI.2014.12.4.283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wallace AC, Laskowski RA, Thornton JM. LIGPLOT: a program to generate schematic diagrams of protein-ligand interactions. Protein Eng. 1995;8:127–134. doi: 10.1093/protein/8.2.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Russell RJ, Haire LF, Stevens DJ, Collins PJ, Lin YP, Blackburn GM, et al. The structure of H5N1 avian influenza neuraminidase suggests new opportunities for drug design. Nature. 2006;443:45–49. doi: 10.1038/nature05114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van der Vries E, Collins PJ, Vachieri SG, Xiong X, Liu J, Walker PA, et al. H1N1 2009 pandemic influenza virus: resistance of the I223R neuraminidase mutant explained by kinetic and structural analysis. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002914. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ramachandran M, Nambikkairaj B, Bakyavathy M. In silico molecular modeling of neuraminidase enzyme H1N1 avian influenza virus and docking with zanamivir ligands. Asian Pac J Trop Dis. 2012;2:426–430. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gupta S, Saxena V, Singh B. Homology modeling and docking studies of neuraminidase protein of influenza A virus (H1N1) virus with select ligand: a computer aided structure based drug design. Int J Pharm Sci Invent. 2013;2:35–41. [Google Scholar]