Abstract

Six free base tetrapyrrolic chromophores, three quinoline-annulated porphyrins and three morpholinobacteriochlorins, that absorb light in the near-IR range and possess, in comparison to regular porphyrins, unusually low fluorescence emission and 1O2 quantum yields were tested with respect to their efficacy as novel molecular photo-acoustic imaging contrast agents in a tissue phantom, providing an up to ~2.5-fold contrast enhancement over that of the benchmark contrast agent ICG. The testing protocol compares the photoacoustic signal output strength upon absorption of approximately the same light energy. Some relationships between photophysical parameters of the dyes and the resulting photoacoustic signal strength could be derived.

Introduction

Photoacoustic imaging (PAI) is a non-invasive biomedical imaging modality that combines optical and ultrasound imaging in such a way that its key characteristics are superior to each of the component imaging techniques.1–3 The absorption of a light pulse by a chromophore causes a rapid and transient rise in temperature (in the order of mK), leading to a localized thermalelastic expansion. As a laser beam pulsed in the nanosecond range is scanned through an object to be imaged, the emitted ultrasonic wave profile is acquired using standard ultrasonic transducers. The data are used to reconstruct 2D or 3D optical absorption maps. PAI is non-invasive and combines the advantages of high optical contrast and ultrasound (sub-mm) spatial resolution.2,4–6

Using the high optical absorption of the endogenous chromophore hemoglobin, PAI proved itself as a powerful tool for imaging the blood content of, for instance, the vascular network of cancers in rodent brains or ovary tissues, in mesoscopic biological objects, or present in whole animals.7 However, to achieve the good signal to noise ratio in reasonably short times that would make PAI of deeply-seated lesions practical, the sensitivity of PAI at greater tissue depths needs to be improved.4 Furthermore, many cancers, particularly in their early stages, cannot be detected by their intrinsic vascular contrast.8 These current shortcomings in PAI suggest, inter alia, the use of exogenous contrast agents.

The native light absorption of tissue is wavelength-dependent, with the least absorbance in the NIR region. For instance, the wavelength of maximum penetration of breast tissue is ~725 nm; whole blood has an absorption minimum at ~710 nm.9 Thus, using near-IR wavelengths within the ‘spectroscopic window’ (~700–1000 nm) allows tissues to be imaged at deeper depth (several cm) than most other optical imaging techniques.

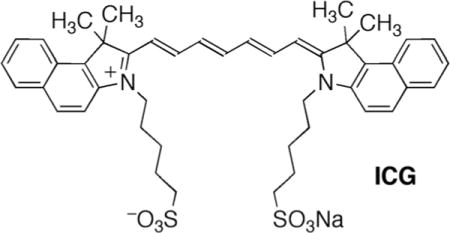

It thus follows that a good PAI contrast agent ought to have a strong absorption in the NIR, particularly in the region between ~700 and 800 nm. The FDA-approved ocular angiographic dye indocyanine green (ICG) and ICG derivatives fulfill this spectroscopic requirement.10 ICG and ICG derivatives were utilized as rare molecular NIR PAI contrast agents even though there are other photophysical parameters – like the significant fluorescence of ICG derivatives, see below – that do not make them ideal PAI contrast agents.11 Irrespective of the shortcomings, the utilization of ICG suggests its use as the benchmark dye.

ICG is confined to the vasculature space and it clears rapidly (t1/2 < 3 min), complicating longitudinal in vivo studies. This led to the development of other contrast agents, such as metal-based nanoparticles combined with and without organic dyes, nanotubes, and porphyrin-based liposomes.2,12 Since the safety of the use of nanoparticles in medicine is as yet unclear,13 it led to the search for novel ways to, for instance, generate dyes in tissue.6,14 For instance, photoacoustic probes activatable by cancer markers were developed.3 Notably rare from all these reports are novel small molecular dyes as PAI contrast agents.15

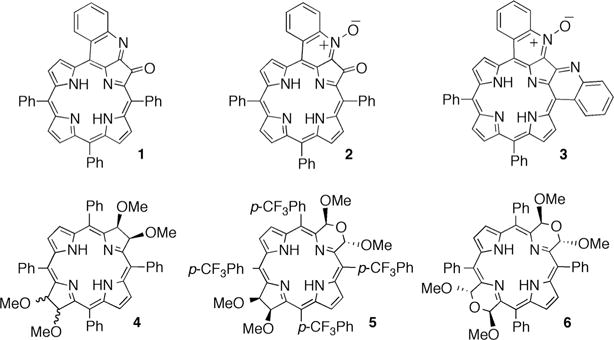

The annulation of carba- and heterocycles to the periphery of porphyrins is an established method to red-shift the optical spectra of porphyrins (regular porphyrins generally do not absorb much past 650 nm).16 We, and independently others,17 recently reported the synthesis of quinoline-annulated porphyrins, such as parent compound 1, its N-oxide 2, and bisquinoline 3.18 As a result of the extended π-conjugation within these chromophores, they are endowed with, for porphyrins, unusually red-shifted λmax bands in the 750 nm range.

Bacteriochlorins (2,3,12,13-tetrahydroporphyrins) are the chromophores of the photosynthetic pigments of anoxygenic photo-autotrophic cyanobacteria and are the light antenna and electron-transfer pigments in strictly anaerobic heliobacteria.19 Bacteriochlorins are characterized by UV-visible spectra with intense absorption bands in the near infrared (NIR) region (>700 nm).20 These optical properties and their ability to generate singlet oxygen make bacteriochlorins very attractive for use as, for instance, photochemotherapeutics21 or light-harvesting systems.22 Preliminary reports on their use as PAI imaging agents have also appeared.15

We prepared the fully synthetic bacteriochlorin 4 by dihydroxylation/alkylation of the corresponding porphyrin.23 Further functional group manipulation leading to ring expansion reactions in the closely related dihydroxy-, dimethoxy- and tetrahydroxy-substituted bacteriochlorins resulted in the formation of the bacteriochlorin analogues 5 and 6, containing one or two morpholino moieties in place of the pyrroline moieties.24 These chromophores are endowed with particularly red-shifted and broadened optical spectra, whereby much of the spectral modulation in the morpholinobacteriochlorins 4 and 6 is presumed to be derived from a conformational modulation of the macrocycle; they are particularly ruffled and are believed to be conformationally flexible.24

We report here the evaluation of the chromophores 1 through 6 as PAI contrast agents in direct comparison to ICG (Fig. 1). We also compare the photophysical characteristics of the chromophores (longest wavelength absorption bands, extinction coefficients, fluorescence and singlet oxygen quantum yields, singlet state lifetimes, and intersystem crossing yields) to their relative efficacy as PAI contrast agents. We are not aware of any study in which a correlation between the photophysical characteristics of a range of NIR dyes and their efficacy as PAI agents using a near-identical irradiance energy was reported. However, the efficacy of a dye as a PAI contrast agent is related to a large number of physical factors, including – but certainly not limited to – the key photophysical properties listed above. Indeed, this study cannot establish any correlation that would possess good predictive values. Nonetheless, we can identify molecular PAI contrast agents that provide better PAI contrast enhancements than the benchmark dye ICG, and we can glean some trends in the photophysical characteristics of a good imaging agent that may guide further investigations.

Fig. 1.

Structures of the NIR chromophores investigated.

Results and discussion

Chromophore selection and their optical properties

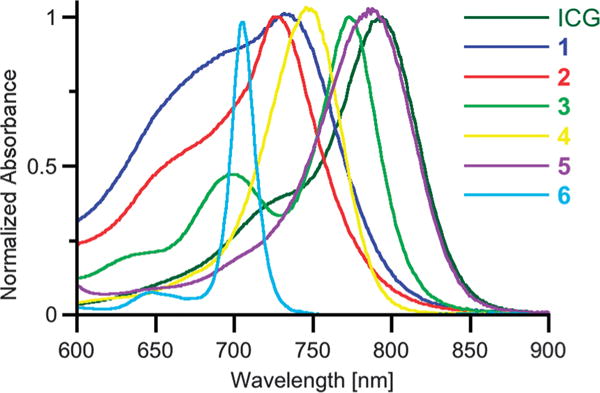

We selected the chromophores 1 through 6 for our investigation because of their UV-Vis-NIR absorption properties. Their λmax values (the wavelengths of the band of longest absorption) in DMF between 726 and 790 nm fall into the spectroscopic window of tissue, and all fall within a range of 70 nm of those of ICG in the same solvent (Fig. 2), allowing for a meaningful direct comparison of the PAI data accrued (for further details, see below).

Fig. 2.

UV-Vis spectra (DMF) of the chromophores used in the PAI experiments. The concentrations were adjusted to an absorption value of 1.0 ± 0.05 at the respective λmax wavelength, 1 cm glass cuvette.

A number of general requirements for a chromophore to render a strong photoacoustic effect can be predicted:3,25 inter alia, the chromophore should possess a high extinction coefficient (ɛ) in the NIR range and fast kinetics of the non-radiative deactivation of the chromophore are required so that all absorbed light energy is rapidly converted to heat, resulting in a strong localized thermo-elastic expansion.

Upon light absorption, porphyrins generally undergo a π → π* transition into an excited singlet state. From there the system either relaxes back to the ground state through fluorescence or thermally through internal conversion (IC). It can also undergo an inter-system crossing (ISC) into an excited triplet state. In turn, the triplet state relaxes either thermally, through phosphorescence or, frequently observed in porphyrins, through interaction with triplet oxygen (3Σg), generating singlet oxygen (1Δg). Thus, the singlet state lifetime (τS1), the fluorescence quantum yield (ΦFluo), the ISC quantum yield (ΦISC), and the singlet oxygen quantum yield (ΦΔ) are crucial parameters to assess the relaxation pathways of the chromophores investigated.

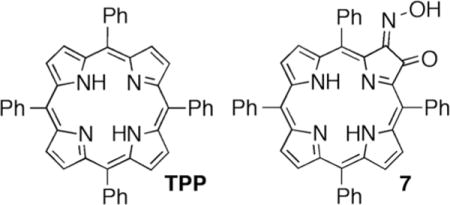

The photophysical characteristics of the quinoline-annulated porphyrins 1 through 3, in comparison to the corresponding data of the benchmark porphyrin TPP and the precursor to the quinoline-annulated porphyrin, oxime 7, are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Photophysical properties of the dyes investigated

| λmax/nm | log ɛ at λmax/cm−1M−1 | ΦFluo/% | ΦISC/% (±3%) | ΦΔn/% (±10%) | (±10%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICG | 776,d 794j | 5.06 | 8g | 0.6h | —i | 0.15h |

| TPPa | 648 | 3.61 | 9 (11)c | 50 | 45 | 0.24 |

| 1k | 728 | 4.30 | <1 | 2 | 5 | 0.04 |

| 2k | 726 | 4.49 | <1 | b.d.e | <1 | b.d.e |

| 3m | 773 | 4.44 | 0.004 | —b | 4o | 0.74, 1.70f |

| 7k,j | 667 | 3.75 | <1 | 27 | 7 | 1.33 |

| 4k,j | 704 | 4.71 | 17 | 45 | 40 | 5.40 |

| 5k,j l | 745 | 4.54 | 3 | 85 | —b | 3.77 |

| 6k,j | 790 | 4.36 | 0.01 | 87 | 12 | 0.45 |

In toluene.

Not determined.

G. H. Barnett, M. F. Hudson, and K. M. Smith, J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. I, 1975, 1401–1403.

At 6.5 μM ICG in H2O, M. L. J. Landsman, G. Kwant, G. A. Mook, W. G. Zijlstra, J. Appl. Physiol., 1976, 40, 575–583.

Below the detection limit.

Biexponential decay.

J. Pauli, R. Brehm, M. Spieles, W. A. Kaiser, I. Hilger, and U. Resch-Genger, J. Fluoresc., 2010, 20, 681–693.

In O2-free H2O. T. Luo, MSc thesis, University of Waterloo, 2008.

While ICG does not appear to generate much, if any, 1O2 upon radiation, it generates medicinally relevant reactive oxygen species: S. Fickweiler, R.-M. Szeimies, W. Bäumler, P. Steinbach, S. Karrer, A. E. Goetz, C. Abels, and F. Hofstädter, J. Photochem. Photobiol. B, 1997, 38, 178–183.

Ref. 22.

λmax and log ɛ in CH2Cl2, all else in DMF.

Data for the closely related meso-tetraphenyl derivative.

λmax and log ɛ in CH2Cl2, all else in DMSO.

λexcitation = λSoret.

At λexcitation = 625 nm, ΦΔ = 21%, a finding rationalized by the presence of non-sensitizing dimers that are excited at λSoret but that do not get excited at 625 nm; instead, strongly sensitizing monomers are addressed. A. Vollertsen, MS thesis, Humboldt-University, Berlin, 2012.

A comparison of the data reveals that the annulated porphyrins are characterized by parameters that are expectedly favorable for their utilization as PAI contrast agents. Specifically, the quinoline-annulated porphyrins 1, 2, and 3 possess comparably higher extinction coefficients at λmax (that are, however, still a factor of ~4 smaller than ɛ of ICG), they possess low fluorescence quantum yields (ΦFluo), low intersystem crossing quantum yields (ΦISC), short S1 state life times , and generate little singlet oxygen (see also below why this is important). These parameters suggest that their excited S1 states relax rapidly along primarily thermal pathways, converting more than 98% of the incident light into heat. Therefore, using a good PAI signal generation can be expected upon irradiation of the quinoline-annulated porphyrins 1 through 3.

The use of porphyrins in diagnostic applications is potentially hampered by the photosensitization of toxic singlet oxygen upon their irradiation in oxygenated environments.26 However, chromophores 1 through 3 are characterized by very low singlet oxygen quantum yields (ΦΔ). Applied in vivo, this reduces the risk of photosensitization-induced oxidative stress upon extended periods of irradiation and also of oxidative chromophore photobleaching.

Some metalloporphyrins possess theoretically better photophysical properties than their corresponding free bases: for instance, the nickel(II) or copper(II) complexes are expected to possess high non-radiative decay rate constants from the excited singlet state and they are expected to not generate any singlet oxygen.27 However, the metal complexes of bacteriochlorins are generally less studied because their preparation poses multiple challenges.20 Moreover, the porphyrinoid metal complexes frequently possess blue-shifted optical spectra, reduced long wavelengths absorptivities, and lower solubilities compared to their free bases.28 We thus opted here for the study of the free base compounds.

A comparison of the photophysical data for oxime 7 and quinoline-annulated system 1 also clearly shows that the imine-type nitrogen substituent or the ketone functionality at the porphyrin β-positions are not the primary origin of the bathochromic spectrum of chromophore 1 or the observed change in the photophysical parameters. A comparison of the data for quinolines 1 and 2 reveals that the presence of the N-oxide only accentuates the trends established by quinoline annulation. Bis-fusion in 3 causes an additional red-shift of λmax but does not improve other key parameters.

The bacteriochlorins 4 through 6 cover a λmax range from slightly above 700 nm for the idealized planar compound 4 to 790 nm for the strongly ruffled bismorpholinobacteriochlorin 6, with 5 occupying a middle position.18 The more planar and presumably conformationally more rigid chromophore 4 possesses a reasonably high fluorescence yield, its ISC yield is higher than those of all other chromophores investigated, it possesses a relatively long S1 state lifetime and corresponding high singlet oxygen quantum yield (that is, however, lower than those reported for other bacteriochlorins suggested as PAI/PDT theranostic agents).15 However, with increasing pyrroline-to-morpholine replacement, increasing nonplanarity and conformational flexibility, the fluorescence yields degrade, and the singlet oxygen yields are diminished (though still high compared to those of the quinoline-substituted chromophores 1 through 3). Also, while the singlet lifetimes are reduced with increasing morpholine substitution, they are still 1–2 orders of magnitude longer than those of the quinoline-annulated systems 3 through 6. In totality, this may suggest that even though their strong absorbance in the NIR is enticing, their long excited state lifetimes may not result in good PA signals.

Evaluation of the chromophores as PAI contrast agents

The Grüneisen coefficient describes the proportionality between the thermal expansion coefficient and the heat capacity of a material (at constant pressure), amounting to the proportionality of the absorbed light energy and the resulting photoacoustic pressure.25 While known for tissues and other bulk materials, this number is not known for chromophore solutions. However, since something equivalent to the Grüneisen parameter could be very useful for the comparison of a number of dyes in dilute solutions, we assessed the NIR-absorbing chromophores 1 through 6 as PAI contrast agents in phantom studies in comparison to ICG in a standardized fashion and to the PAI signal obtained from a pure blood sample. The data derived from these experiments approximate the comparative value of the Grüneisen parameter.

We performed two series of experiments. In one, we prepared solutions of the dyes 1 through 3 and ICG in PBS–1% DMF–1% Cremophore EL® at concentrations that resulted all solutions to possess an equal absorption at λmax (O.D. of 1.0 at 1 cm path length, see Fig. 2), and we irradiated at λmax. Since all solutions absorbed within a narrow window, the energy input difference between the extremes of λmax is less than 9%. Empirically, we find the data of the PAI experiments to vary upon replication by up to 7%, i.e. the simplification of using different irradiation wavelengths/energies at equal absorbance values is within acceptable limits. We then performed the phantom studies described below, the results of which are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparison of the PAI signal strengths in the phantom studya

| λirradiation/nm | Relative PAI signal strength at 1 cm depth | Relative PAI signal strength at 2 cm depth | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ICG | 790 | 1.0b (1.0)c | 1.0b (1.0)c |

| By definition | By definition | ||

| Bloode | 750 | 1.1 | 1.0 |

| 1 | 765 | 2.5b (1.6)d | 2.4b (1.5)d |

| 2 | 755 | 1.9b (1.4)d | 1.2b (1.4)d |

| 3 | 780 | 1.7b (1.0)d | 1.1b (1.1)d |

| 4 | 715 | —f | —f |

| 5 | 765 | 0.5b | 0.5b |

| 6 | 741 | 0.8b | 0.7b |

The concentrations of the dyes were adjusted to an equal absorbance value of A = 1.0 in a 1.0 cm path length cell.

Solvent DMF.

Solvent PBS.

Solvent PBS–1% DMF–1% Cremophore EL® and λirradiation = λSoret, see Table 1.

Day-old whole rat blood, used as is, λirradiation = 750 nm.

PAI signal strength below the detection limit.

To allow a much better direct comparison of the PAI signal strength generated by ICG, a blood sample, and any given dye and to allow a correlation to the photophysical data measured primarily in DMF (Table 1), we set up a second series of experiments. The spectra of the dyes 1 through 6 all overlap with the spectrum of ICG. Thus, DMF solutions of the dyes and ICG were prepared and the isoabsorbance point for each dye– ICG pair was determined. Then the concentration of the solutions was adjusted to an O.D. of 1.0 at the isoabsorbance wavelength (at 1 cm path length; see Table 2 for the λirradiation used), thus assuring that each ICG–dye pair would receive the identical energy input upon irradiation at this wavelength. The blood sample was used as is and irradiated at 750 nm, an arbitrary wavelength in the middle of the range of the λirradiation used.

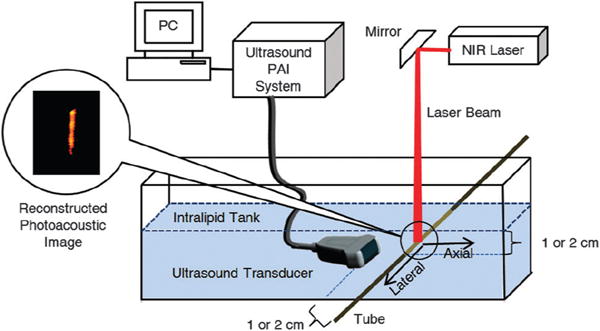

The phantom studies to evaluate the dyes relative to ICG were performed using the set-up shown in Fig. 3. A translucent polyethylene tube with an inner diameter of 0.38 mm was filled with the standard DMF solutions of the dyes 1 through 6 and ICG. The tube was immersed at 1.0 and 2.0 cm depths in a tank filled with a 4% intralipid suspension, a white opaque emulsion of soy bean oil, egg phospholipids and glycerin. This emulsion is widely used to simulate the scattering properties of biological tissues at wavelengths in the red and infrared ranges where tissue highly scatters but has a rather low absorption coefficient.29

Fig. 3.

PAI experimental setup. Details: Nd:YAG-pumped tunable Ti:sapphire laser, average power of 18 mJ cm−2; ultrasound transducer of central frequency 1.3 MHz and bandwidth of 80%, connected to a 64 channel ultrasound PAI system.

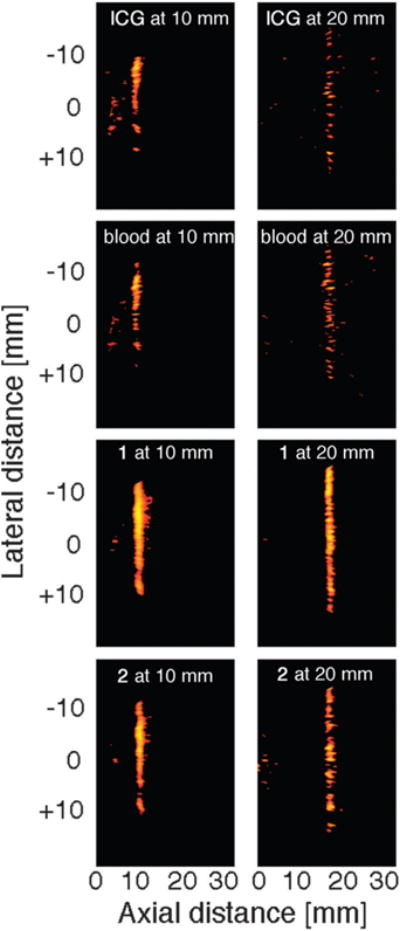

Upon illumination with an NIR laser tuned to the λirradiation chosen and spread to 2 cm diameter width at the point where it intersected with the tube, the photoacoustic measurements were recorded for each sample solution using a commercial low-frequency transducer array. The array was held at a fixed position 1.0 cm and 2.0 cm away from the center of the intersection of the NIR beam and the tube, respectively. The PA signal was collected and processed using a PAI system. Photoacoustic images were reconstructed using a typical ultrasound beam forming algorithm based on the transducer array geometry (for details of the system, see Experimental section). The data thus obtained were plotted using a color scale, providing the photoacoustic images shown in Fig. 4. The PAI signal strengths relative to those obtained for ICG in the same solvents are listed in Table 2.

Fig. 4.

Photoacoustic images of the dyes indicated, dissolved in an aqueous solution containing the surfactant Cremophore EL to a concentration resulting in an absorbance value of A = 1.0 at 1.0 cm path lengths. Left column: targets located at 1 cm depth, the right column shows targets located at 2 cm depth. Targets: a transparent polyethylene tube of inner diameter 0.38 mm and outer diameter 1.09 mm filled with the dye solution, submersed in an opaque 4% intralipid suspension. To best visualize the contrast, the dynamic range of the display was set to 10 dB.

At 1 cm depth–detector distance, all dyes tested provide a clear image of the target. However, the intensity of the signal varied. The signal strengths recorded for the quinoline-annulated porphyrins 1 through 3 are 1.7 to 2.5-fold stronger than the signal for the benchmark compound ICG or the blood sample (that showed very similar PAI signal strengths to those obtained with ICG), with compound 1 providing the best signal. The signal strength recorded for 1 is still nearly 2.4-fold stronger at 2 cm immersion depth–detector distance, though the relative advantages of these dyes in DMF over ICG are largely eroded. A comparison of the photophysical data for the dyes (Table 1) with the PAI data (Table 2) reveals that the best PAI contrast agent 1 is mostly differentiated from the other two structurally similar compounds (and ICG) by possessing the shortest singlet state lifetime, suggesting that this may have been the crucial factor for its relatively high efficacy.30

Using an aqueous solvent for the comparison of the three dyes with ICG, the absolute signal strength and the relative signal strength advantages of the dyes 1 through 3 are not as strong. Given the lower heat capacity of DMF (1.88 J K−1 cm−3) compared to that of water (4.19 J K−1 cm−3) (and ignoring factors such as their varying thermal pressure coefficients),30 the lower light absorption-induced photoacoustic pressure in water does not surprise. The fact, however, that the relative drop in the signal strengths with the phantom immersion depth–detector distance is not as steep when using the aqueous solvent versus DMF does not find a simple explanation.

As a result of the higher signal-to-noise ratios, the PAI images recorded with dyes 1 and 2 also show a better-defined tubing structure than the image recorded with ICG (Fig. 3; note that the images shown were recorded using aqueous solvents). The signal strength recorded for 3 (no image shown) was identical to that recorded for ICG. However, the ~4-fold higher absorptivity of ICG compared to the porphyrinoids at around 750 nm suggests that ICG is still a better contrast agent at equal concentrations.

As, perhaps, could be predicted based on their higher fluorescence quantum yields, larger ISC yields, longer-lived excited singlet states, and higher singlet oxygen quantum yields, the bacteriochlorins 4 through 6 did not perform as well as the quinoline-annulated porphyrins or ICG in the PAI experiments. This illustrates well the need to fine-tune all photophysical properties of a potential PAI imaging dye, not just their optimal absorption properties. On the other hand, the ability to induce a PAI signal when irradiated with NIR light as well as to generate ROS suggest their utilization in theranostic applications, as suggested by Arnaut and co-workers.15

Conclusions

We have shown the direct comparsion of a range of porphyrinoids with NIR absorbing properties belonging to two different compound classes (quinoline-annulated porphyrins and bacteriochlorins) as exogenous PAI imaging contrast agents in phantom studies. We demonstrated the imaging of a sub-mm target at up to 2 cm depth in a tissue-like matrix whereby some porphyrinoids matched or exceeded the performance of the benchmark dye ICG at equal absorbance or the performance of pure blood. This suggests the use of quinoline-annulated porphyrins as potential contrast agents for in vivo use for multi-cm deep tissue PAI. While our data do not allow any obvious direct correlations between the photophysical data and the PAI contrast enhancement measured to be made, the need for the ability of the dyes to access a very efficient thermal relaxation pathway is once again highlighted. Moreover, as we are screening more members of NIR-absorbing porphyrinoids using the simple and rapid screening tool used here, a direct correlation between the PAI signal strength and key photophysical parameters may come into focus, further assisting in the design of optimized contrast agents.

The best contrast agents identified in this study, the two quinoline-annulated porphyrins, are currently undergoing a range of in cyto and in vivo cytotoxicity and PAI studies. Preliminary data suggest that the dyes possess low light and dark toxicity; the details of these investigations will be reported in due course.

Experimental

Materials

The porphyinic dyes 1 through 3, as well as their precursor 7, were prepared from TPP as described in the literature.18 The bacteriochlorins 4 though 6 were also prepared from TPP as previously described.23 All solvents were of spectroscopic grade and used as received. Cremophore EL® was acquired from Acros. ICG was purchased from Sigma Aldrich.

The dyes 1 through 6 and ICG were dissolved in DMF at a concentration so that they possess all identical absorbances (A = 1.0 at the wavelengths listed in Table 2 at 1 cm path length). The dyes 1 through 3 and ICG were also tested in an aqueous solution using the FDA-approved excipient Cremophore EL®, also at A = 1.0 at λSoret.31

Photophysical measurements

The UV/Vis spectra shown in Fig. 2 were recorded on a Cary 50 spectrophotometer. The absorption data listed in Table 1 were recorded at room temperature on a Shimadzu UV/VIS-160 spectrophotometer. The molar extinction coefficients ɛ(λ) were determined by means of serial dilutions resulting in concentration curves. Steady-state fluorescence spectra were also recorded to determine fluorescence quantum yields (ΦFl) using different standards (TPP in toluene, ΦFFl,TPP = 0.11; TPPS in H2O, ΦFl,TPPS = 0.09; Rhodamine 6G in H2O, ΦFl,Rh = 0.90). A Xe-lamp (XBO 150, OSRAM) with a monochromator was used for excitation. For the emission detection a polychromator with a cooled CCD-matrix (LotOriel, Instaspec IV, 77131) was used.

Time-resolved fluorescence spectroscopy was performed in low-concentration samples (OD ≈ 0.1 at excitation wavelength) via the time-correlated single photon counting (TCSPC) technique, thus yielding fluorescence decay curves. The excitation source used was a pulsed, frequency-doubled Nd:VO4 laser (Cougar, Time Bandwith Products) with λexc = 532 nm, a pulse width of 12 ps and a repetition rate of 60 MHz. The response function of the system was determined using a Ludox scattering solution (Aldrich). Data were analyzed using a homemade program based on the Nelder–Mead simplex algorithm to obtain fluorescence lifetimes τFl.

Intersystem crossing quantum yields (ΦISC) were measured by transient absorption spectroscopy. To measure transient absorption spectra, a white light continuum was generated (test pulse) in a cell containing a D2O–H2O mixture using highly intense, 25 ps-wide pulses from a Nd3+:YAG laser (PL 2143A, Ekspla) of 1064 nm wavelength. On its way to the sample, the white continuum pulse was split to generate a reference spectrum. Both the transmitted and reference beam were focused into optical fibers and recorded simultaneously at different traces on a CCD-matrix (LotOriel, Instaspec IV, 77131). Tunable radiation from an OPG/OPA (Ekspla PG 401/SH, tuning range: 200–2300 nm) pumped by the TH (355 nm) of the same laser was used for excitation. A propagation delay line enables the measurement of light-induced changes of the absorption spectrum at different delay times up to 15 ns after excitation. The absorbance (OD) of all samples was 1.0 at the maximum of the lowest-energy absorption band.

Photoacoustic phantom studies

A translucent polyethylene tube with an inner diameter of 0.38 mm and outer diameter of 1.09 mm was filled with the standard solutions of the dyes 1 through 6, ICG and day-old whole rat blood. The tube was immersed at 1.0 and 2.0 cm depths in a tank filled with a 4% intralipid suspension. Upon illumination with an NIR laser tuned to the λmax of the dye investigated (Table 1) and spread to 2 cm diameter width at the point where it intersected with the tube, the photoacoustic measurements were recorded for each sample solution using a commercial low-frequency transducer array (produced by Vermon, France), and consisted of 64 elements with 0.85 mm pitch. The center frequency of the transducer was 1.3 MHz and bandwidth of 80%, connected to a 64 channel ultrasound PAI system. The array was held at 1.0 and 2.0 cm, respectively, away from the center of the intersection of the NIR beam and the tube. The beam was provided by an Nd:YAG-pumped tunable Ti:sapphire laser with an average power of radiant exposure of 18 mJ cm−2, i.e., well below the ANSI limits of 21 mJ cm−2, for the shortest wavelengths used.32 The signal was then collected and processed by a 64 channel ultrasound PAI system with a scalable center frequency and bandwidth of the ultrasound transducer: imaging speed 5 frames per s and utilizing a unique field programmable gate array (FPGA) based reconfigurable processor that allows real-time switching and interlacing between the two imaging modalities (i.e. ultrasound and photo-acoustic imaging). The system features a modular design and the ability of real-time parallel acquisition from 64 channels with each channel sampled at 40 MHz.33 Photoacoustic images were reconstructed using a typical ultrasound beam forming algorithm based on the transducer array geometry. These images were then plotted using a color scale, providing the photoacoustic images shown in Fig. 4.

Notes and references

- 1.Xua M, Wang LV. Rev Sci Instrum. 2006;77:041101–041122. [Google Scholar]; Pysz MA, Gambhir SS, Willmann JK. Clin Radiol. 2010;65:500–516. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2010.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Wang LV. Nat Photonics. 2009;3:503–509. doi: 10.1038/nphoton.2009.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim C, Favazza C, Wang LV. Chem Rev. 2010;110:2756–2782. doi: 10.1021/cr900266s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levi J, Kothapalli SR, Ma TJ, Hartman K, Khuri-Yakub BT, Gambhir SS. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:11264–11269. doi: 10.1021/ja104000a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Esenaliev RO, Karabutov AA, Oraevsky AA. IEEE J Sel Top Quantum Electron. 1999;5:981–988. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kruger RA, Reinecke DR, Kruger GA. Med Phys. 1999;26:1832–1837. doi: 10.1118/1.598688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stender AS, Marchuk K, Liu C, Sander S, Meyer MW, Smith EA, Neupane B, Wang G, Li J, Cheng JX, Huang B, Fang N. Chem Rev. 2013;113:2469–2527. doi: 10.1021/cr300336e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holen CGA, de Mul FFM, Pongers R, Dekker A. Opt Lett. 1998;23:648–650. doi: 10.1364/ol.23.000648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Wang XD, Pang YJ, Ku G, Xie XY, Stoica G. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:803–806. doi: 10.1038/nbt839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Aguirre A, Guo P, Gamelin J, Yan S, Sanders MM, Brewer M, Zhu Q. J Biomed Opt. 2009;14:0540141–0540149. doi: 10.1117/1.3233916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Ma R, Taruttis A, Ntziachristos V, Razansky D. Opt Express. 2009;17:21414–21426. doi: 10.1364/OE.17.021414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Razansky1 D, Vinegoni C, Ntziachristos V. Phys Med Biol. 2009;54:2769–2777. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/54/9/012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Troy TL, Page DL, Sevick-Muraca EM. J Biomed Opt. 1996;1:342–355. doi: 10.1117/12.239905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cerussi AE, Berger AJ, Bevilacqua F, Shah N, Jakubowski D, Butler J, Holcombe RF, Tromberg BJ. Acad Radiol. 2001;8:211–218. doi: 10.1016/S1076-6332(03)80529-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luo S, Zhang E, Su Y, Cheng T, Shi C. Biomaterials. 2011;32:7127–7138. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang X, Ku G, Wegiel MA, Bornhop DJ, Stoica G, Wang LH. Opt Lett. 2004;29:730–732. doi: 10.1364/ol.29.000730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Ku G, Wang LV. Opt Lett. 2005;30:507–509. doi: 10.1364/ol.30.000507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Wang B, Qing Z, Barkey NM, Morse DL, Jiang H. Med Phys. 2012;39:2512–2517. doi: 10.1118/1.3700401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De La Zerda A, Zavaleta C, Keren S, Vaithilingam S, Bodapati S, Liu Z, Levi J, Smith BR, Ma TJ, Oralkan O, Cheng Z, Chen X, Dai H, Khuri-Yakub BT, Gambhir SS. Nat Nanotechnol. 2008;3:557–562. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2008.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Song KH, Kim C, Cobley CM, Xia Y, Wang LV. Nano Lett. 2008;9:183–188. doi: 10.1021/nl802746w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Yang X, Skrabalak S, Stein E, Wu B, Wei X. Proc SPIE. 2008;6856:6856601. [Google Scholar]; Wang B, Yantsen E, Larson T, Karpiouk AB, Sethuraman S, Su JL, Sokolov K, Emelianov SY. Nano Lett. 2008;9:2212–2217. doi: 10.1021/nl801852e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Mallidi S, Larson T, Tam J, Joshi PP, Karpiouk A, Sokolov K, Emelianov S. Nano Lett. 2009;9:2825–2831. doi: 10.1021/nl802929u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Pan D, Pramanik M, Senpan A, Yang X, Song KH, Scott MJ, Zhang H, Gaffney PJ, Wickline SA, Wang LV, Lanza GM. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2009;48:4170–4173. doi: 10.1002/anie.200805947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Yang X, Stein EW, Ashkenazi S, Wang LV. WIREs Nanomed Nanobiotech. 2009;1:260–368. doi: 10.1002/wnan.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Chen J, Yang M, Zhang Q, Cho EC, Cobley CM, Kim C, Glaus C, Wang LV, Welch MJ, Xia Y. Adv Funct Mater. 2010;20:3684–3694. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201001329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d l Zerda A, Liu Z, Bodapati S, Teed R, Vaithilingam S, Khuri-Yakub BT, Chen X, Dai H, Gambhir SS. Nano Lett. 2010;10:2168–2172. doi: 10.1021/nl100890d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Lovell JF, Jin CS, Huynh E, Jin H, Kim C, Rubinstein JL, Chan WCW, Cao W, Wang LV, Zheng G. Nat Mater. 2011;10:324–332. doi: 10.1038/nmat2986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Moon GD, Choi SW, Cai X, Li W, Cho EC, Jeong U, Wang LV, Xia Y. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:4762–4765. doi: 10.1021/ja200894u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Pan D, Cai X, Yalaz C, Senpan A, Omanakuttan K, Wickline SA, Wang LV, Lanza GM. ACS Nano. 2012;6:1260–1267. doi: 10.1021/nn203895n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Jokerst JV, Cole AJ, Van de Sompel D, Gambhir SS. ACS Nano. 2012;6:10366–10377. doi: 10.1021/nn304347g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Ku G, Zhou M, Song S, Huang Q, Hazle J, Li C. ACS Nano. 2012;6:7489–7496. doi: 10.1021/nn302782y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Jokerst JV, Thangaraj M, Kempen PJ, Sinclair R, Gambhir SS. ACS Nano. 2012;6:5920–5930. doi: 10.1021/nn302042y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; de la Zerda A, Bodapati S, Teed R, May SNY, Tabakman SM, Liu Z, Khuri-Yakub BT, Chen X, Dai H, Gambhir SS. ACS Nano. 2012;6:4694–4701. doi: 10.1021/nn204352r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Homan KA, Souza M, Truby R, Luke GP, Green C, Vreeland E, Emelianov S. ACS Nano. 2012;6:641–650. doi: 10.1021/nn204100n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Cook JR, Frey W, Emelianov S. ACS Nano. 2013;7:1272–1280. doi: 10.1021/nn304739s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heister E, Brunner EW, Dieckmann GR, Jurewicz I, Dalton AB. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2013;5:1870–1891. doi: 10.1021/am302902d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Filonov GS, Krumholz A, Xia J, Yao J, Wang LV, Verkhusha VV. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2011;51:1448–1451. doi: 10.1002/anie.201107026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Zhang Y, Cai X, Wang Y, Zhang C, Li L, Choi SW, Wang LV, Xia Y. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2011;50:7359–7363. doi: 10.1002/anie.201101659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schaberle FA, Arnaut LG, Serpa C, Silva EFF, Pereira MM, Abreu AR, Simões S. Proc SPIE. 2010;7376:7376X. [Google Scholar]; Schaberle FA, Reis LAF, Sá GFF, Serpa C, Abreu AR, Pereira MM, Arnaut LG. Proc SPIE. 2011;8089:8089Q. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rogers JE, Nguyen KA, Hufnagle DC, McLean DG, Su W, Gossett KM, Burke AR, Vinogradov SA, Pachter R, Fleitz PA. J Phys Chem A. 2003;107:11331–11339. [Google Scholar]; Fox S, Boyle RW. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:10039–10054. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jeandon C, Ruppert R. Eur J Org Chem. 2011:4098–4102. [Google Scholar]; Pereira AMVM, Richeter S, Jeandon C, Gisselbrecht JP, Wytko J, Ruppert R. J Porphyrins Phthalocyanines. 2012;16:464–478. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Akhigbe J, Zeller M, Brückner C. Org Lett. 2011;13:1322–1325. doi: 10.1021/ol1031848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scheer H. In: Chlorophylls and Bacteriochlorophylls. Grimm B, Porra RJ, Rüdinger W, Scheer H, editors. Springer; Dordrecht, NL: 2006. pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brückner C, Samankumara L, Ogikubo J. In: Handbook of Porphyrin Science. Kadish KM, Smith KM, Guilard R, editors. Vol. 17. World Scientific; River Edge, NY: 2012. pp. 1–112. (Synthetic Developments, Part II), ch. 76. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen Y, Potter WR, Missert JR, Morgan J, Pandey RK. Bioconjugate Chem. 2007;18:1460–1473. doi: 10.1021/bc070092i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Chen Y, Li G, Pandey RK. Curr Org Chem. 2004;8:1105–1134. [Google Scholar]; Mroz P, Huang YY, Szokalska A, Zhiyentayev T, Janjua S, Nifli AP, Sherwood ME, Ruzie C, Borbas KE, Fan D, Krayer M, Balasubramanian T, Yang E, Kee HL, Kirmaier C, Diers JR, Bocian DF, Holten D, Lindsey JS, Hamblin MR. FASEB J. 2010;24:3160–3170. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-152587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Huang YY, Mroz P, Zhiyentayev T, Sharma SK, Balasubramanian T, Ruzie C, Krayer M, Fan D, Borbas KE, Yang E, Kee HL, Kirmaier C, Diers JR, Bocian DF, Holten D, Lindsey JS, Hamblin MR. J Med Chem. 2010;53:4018–4027. doi: 10.1021/jm901908s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Fukuzumi S, Ohkubo K, Zheng X, Chen Y, Pandey RK, Zhan R, Kadish KM. J Phys Chem B. 2008;112:2738–2746. doi: 10.1021/jp0766757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Yerushalmi R, Ashur I, Scherz A. In: Chlorophylls and Bacteriochlorophylls. Grimm B, Porra RJ, Rüdinger W, Scheer H, editors. Springer; Dordrecht, NL: 2006. pp. 495–506. [Google Scholar]; Huang L, Huang YY, Mroz P, Tegos GP, Zhiyentayev T, Sharma SK, Lu Z, Balasubramanian T, Krayer M, Ruzie C, Yang E, Kee HL, Kirmaier C, Diers JR, Bocian DF, Holten D, Lindsey JS, Hamblin MR. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:3834–3841. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00125-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Springer JW, Parkes-Loach PS, Reddy KR, Krayer M, Jiao J, Lee GM, Niedzwiedzki DM, Harris MA, Kirmaier C, Bocian DF, Lindsey JS, Holten D, Loach PA. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:4589–4599. doi: 10.1021/ja207390y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Samankumara LP, Zeller M, Krause JA, Brückner C. Org Biomol Chem. 2010;8:1951–1965. doi: 10.1039/b924539a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Samankumara LP, Wells S, Zeller M, Acuña AM, Röder B, Brückner C. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2012;51:5757–5760. doi: 10.1002/anie.201201124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Larina IV, Larin KV, Esenaliev RO. J Phys D: Appl Phys. 2005;38:2633–2639. [Google Scholar]

- 26.The strong fluorescence and generally good 1O2 photosensitization ability of porphyrins is the basis of their utilization as imaging and photochemotherapeutics:; Ethirajan M, Chen Y, Joshi P, Pandey RK. Chem Soc Rev. 2011;40:340–362. doi: 10.1039/b915149b. See also ref. 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Drain CM, Gentemann S, Roberts JA, Nelson NY, Medforth CJ, Jia S, Simpson MC, Smith KM, Fajer J, Shelnutt JA, Holten D. J Am Chem Soc. 1998;120:3781–3791. [Google Scholar]; Retsek JL, Drain CM, Kirmaier C, Nurco DJ, Medforth CJ, Smith KM, Sazanovich IV, Chirvony VS, Fajer J, Holten D. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:9787–9800. doi: 10.1021/ja020611m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Buchler JW. In: Porphyrins. Dolphin D, editor. Vol. 1. 1978. pp. 389–483. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Driver I, Feather JW, King PR, Dawson JB. Phys Med Biol. 1989;34:1927–1930. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arnaut LG, Caldwell RA, Elbert JE, Melton LA. Rev Sci Instrum. 1992;63:5381–5389. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cremophor EL (BASF), a polyethoxylated castor oil with excellent surfactant qualities.

- 32.ANSI Z136.1-2007: American National Standard for Safe Use of Lasers, American National Standards Institute Inc. 2007

- 33.Alqasemi U, Li H, Aguirre A, Zhu Q. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control. 2012;59:1344–1353. doi: 10.1109/TUFFC.2012.2335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]