Abstract

Introduction

We examined the effect of seasonal variation on sexual behavior and its relationship with testosterone levels. The existence of the inhibiting effect of cold stress on sexual behavior and testosterone levels was our hypothesis.

Material and methods

A total of 80 cases, aged between 20 and 35 years old, were enrolled. Blood samples for testosterone, FSH, LH, and prolactin were obtained twice from each participant at the same time of day (before 10 am). The first samples were taken in January and February, the months which have the average lowest heat days (-15.9°C and -14.6°C, respectively) in our region. The second samples were taken in July and August, which has the average highest heat days (25.4°C and 26.1°C, respectively) in our region. Two times IIEFs (International Index of Erectil Function) were fulfilled at the same day of taking blood samples. The frequency of sexual thoughts and ejaculation were questioned by asking “How many times did you imagine having sex?’’ and “How many times did you ejaculate in a week?”. The body mass index of the participants in the study was calculated in the winter and in the summer.

Results

There were significant differences in terms of IIEF scores, frequency of sexual thoughts and ejaculations, BMI (Body mass index), and both testosterone and FSH levels between the winter and summer measurements. We did not find any significant differences with regards to prolactin and LH levels.

Conclusions

Although testosterone levels are within normal limits in both seasons, its level in cold months is less than in hot months. Testosterone levels can change according to the season. The impact of cold seasons in particular should be taken into account when evaluating testosterone levels and sexual status, as well as the other influences (social, cultural).

Keywords: seasonal variation, cold stress, sexual behavior, testosterone

INTRODUCTION

Sex is a fundamental part of the human life that is expressed in countless ways of varying depth and complexity. The reality that men and women think about one another as potential partners, flirt, tell salacious jokes, and sometimes even end up having sex is the basis for television shows, movies, books, and everyday office gossip [1]. Does frequency of such behavior change seasonally?

According to a special report by Lauritsen et al. regarding seasonal patterns in criminal victimization trends, adult rates of simple assault exhibited relatively less seasonal fluctuation but were highest in the summer [2]. Can testosterone be a culprit in such crimes?

Numerous experimental and clinical studies have investigated stress factors such as immobilization, heat, light, electrical foot shocks, cold, ether, exercise, and food restriction that cause males to experience anxiety about their sexual behavior [3, 4]. There may be many factors that regulate male sexual behavior, as well as the psychological mood. Males under stress may exhibit suppression of testosterone secretion, spermatogenesis, and libido [3]. Cold has been regarded as a stress factor in many experimental studies [3, 5]. Cold stress has been defined as acute and chronic cold stress in terms of exposure time, according to animal studies [5]. It is defined as expose to the cold at +4°C for 8 hours for only once and +4°C for 4 hours daily for at least 21 days, for acute and chronic cold stress, respectively [5].

Our region is one of the coldest areas in eastern Turkey. The average lowest temperatures for January and February are -15.9°C and -14.6°C, respectively. The average highest temperatures in July and August are 25.4°C and 26.1°C, respectively according to the data from Turkey Meteorology Institute. In this study, we examined the seasonal variation on sexual behavior and its relationship with testosterone levels. The existence of the inhibiting effect of cold stress on sexual behavior and testosterone levels was our hypothesis.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

The study was designed as a non-randomized prospective trial. Permission for the study was obtained from the Regional Ethics Committee and performed in accordance with the World Medical Association’s Helsinki Declaration (Ethics Committee approval number: 80576354-050-99/01). Informed consent was received from all cases.

A total of 80 cases living in Kars over one year, aged between 20 and 35 years old, were enrolled into the study. All cases in this study were married. The participants were in particular chosen from the ones who work outdoors in their work place or who are exposed to the cold for at least one hour, for instance walking in the morning and evening hours to their work place and home in their normal winter clothes. Our participants were exposed to the cold for at least 60 days (the two coldest months in our region) at -15.9°C and -14.6°C, respectively, which was slightly different from the chronic cold stress definition in terms of exposure time and coldness degree. Blood samples were obtained from the participants at the end of February.

Exclusion criterias

The cases with erectile dysfunction (psychogenic or organic etiology), who are single, those in whom the ejaculations were produced by nocturnal imagination, psychological problems, drug-using history, or libido failure, those with a low hormone profile in terms of testosterone, prolactin, follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), or luteinizing hormone (LH), and the cases who have any abnormal genital physical examination such as varicocele or atrophic testis were excluded from the study.

Blood samples were obtained twice from each participant at the same time of day (before 10 am). The first samples were taken at the end of February. The second samples were taken at the end of August. International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) forms were fulfilled at the same day of taking blood sample twice over the course of the study. The frequency of sexual thoughts and ejaculation were questioned by asking on a special form “How many times did you imagine having sex?’’ and “How many times did you ejaculate in a week, except ejaculations produced by nocturnal imagination?”. The body mass index of the participants in the study was calculated at the same day of taking blood sample.

Statistical analysis

This study was designed to detect a 30% difference in hormone levels between the groups with 90% power, assuming a significance level of 0.05 using two-tailed statistical tests. Sample size was calculated based on the results of a pilot study of hormone levels in consultation with a biostatistics specialist. Results are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Data were analyzed using SPSS 16.0 for Windows (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Differences between the results in terms of hormones, body mass indices (BMI), IIEF scores, and frequency of sexual thoughts were analyzed using paired-samples student t tests.

RESULTS

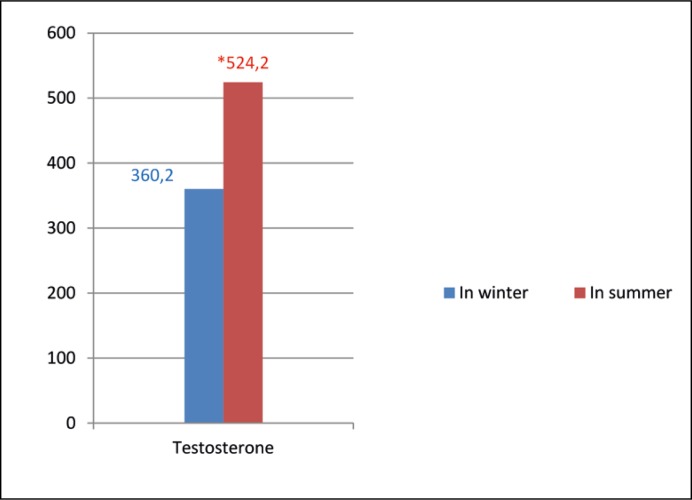

The mean age of the patients was 27.8 years (min: 20, max: 35). There were significant differences in terms of IIEF scores (24.05 ±2.1 and 24.5 ±1.7, p = 0.006), frequency of sexual thoughts (17.4 ±11.04 and 28.1 ±14.1, p = 0.001) and ejaculations (2.31 ±1.15 and 7.16 ±2.49, p = 0.001), BMI (25.7 ±6.1 and 26.16 ±8.15 kg/m2, p = 0.002) and both testosterone (360.2 ±107.4 and 524.2 ±130.01 ng/dL, p = 0.001) and FSH levels (3.77 ±2.47 and 4.3 ±2.8 mIU/ml, p = 0.03) (Table 1, Figure 1) between the winter and summer measurements. We did not find any significant differences with regards to prolactin and LH levels (Table 1).

Table 1.

The results with the standard deviations of study, significance p <0.05

| n=80 | In winter | In summer | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | |||

| IIEF scores | 24.05 ±2.1 | 24.5 ±1.7 | 0.006 |

| Frequency/ week | 17.4 ±11.04 | 28.1 ±14.1 | 0.001 |

| Ejaculation/week | 2.31 ±1.15 | 7.16 ±2.49 | 0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.7 ±6.1 | 26.1 6 ±8.15 | 0.002 |

| Testosterone (ng/dL) | 360.2 ±107.4 | 524.2 ±130.01 | 0.001 |

| FSH (mIU/ml) | 3.77 ±2.47 | 4.3 ±2.8 | 0.03 |

| LH (mIU/ml) | 4.75 ±1.83 | 4.77 ±1.53 | 0.93 |

| Prolactine (ng/ml) | 7.95 ±3.6 | 11.2 ±4.2 | 0.25 |

Figure 1.

Testosterone levels according to the season, *p <0.05. Testosterone: ng/dL (218–906 ng/dL).

DISCUSSION

Ample evidence exists to support the concept of diurnal changes in testosterone levels, but, substantiations for seasonal fluctuations is rare and inconsistent. Since circadian disparities exist, the blood samples have traditionally been obtained in order to know the testosterone levels in the early morning. Current research suggests that while some evidence exists to support the notion of seasonal testosterone changes, the discussed inconsistencies preclude the incorporation of this concept into current clinical standards [6].

Moskovic et al. investigated seasonal fluctuations in some hormones, including testosterone, in men by month and by season. According to their results, no differences in testosterone or free testosterone were established. Statistically significant evidence of changes in estradiol and testosterone/estrogen ratio were identified in men included in their study. According to their comments, although this is consistent with seasonal body habitus changes, physical activity levels, and hypothesized hormonal patterns, the variability reported in the literature makes further trials covering a broader geographic region important to confirm the findings [7].

Testosterone has been shown to follow a seasonal variation in many species, especially in males, that can promote changes in human behavior and physiology, such as waist-to-hip ratio, relationship status, and sexual intercourse [8]. While the majority of studies report that testosterone concentrations peak in the fall for men, other have reported peaks during other months of the year. Inconsistencies in prior findings may have resulted from the varied nature of different studies; some used atypical populations, used participants of only one sex, or collected samples over less than a full year. For that reason, the nature of the seasonal variation in humans’ testosterone concentrations remains poorly characterized [8].

Cold is an interesting and poorly investigated factor that may significantly affect human physiology. A study showed that in tropical men who were acclimatized to Antarctica cold, exposure to cold for various durations caused increased excretion of urinary epinephrine, norepinephrine, and salivary cortisol levels associated with significant autonomic changes in heart rate and blood pressure [5]. So, in this work, we aimed to understand the cold effect in terms of seasonal variations on the hormone profile, including testosterone, LH, FSH, and prolactin and sexual behaviors.

The hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis has a critical role for the development and adulthood in four physiological processes: 1) phenotypic gender development during embryogenesis, 2) sexual maturation at puberty, 3) testis endocrine function- testosterone production, and 4) testis exocrine function-sperm production [9]. Androgen affects the growth and development of the male reproductive system and secondary sex characteristics, as well as the libido and sexual behavior [9]. According to the Mulligan and Schmitt’s study, testosterone enhances sexual interest and increases the frequency of sexual acts and nocturnal erection, but has little or no effect on fantasy – induced or visually – stimulated erections [10]. The most important hypothalamic hormone for androgen production is gonadotropin-releasing or luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (GnRH or LHRH). GnRH secretion results from an integrated input from the effects of stress, exercise, and diet from higher brain centers [9]. The stress response to physical or psychological stressors can affect the HPG axis by inhibiting it [4].

The magnitude of the stress depends on the type and duration of the stressor [11]. According to the model in several studies, acute stress exposure can change from seconds to a few hours, and chronic stress exposure usually lasts at least 20 days [3]. According to these models, our study is acceptable as a chronic stress exposure because of the exposure time that was about 60 days at -15.9°C and -14.6°C degrees. In some studies, while acute stress did not modify testosterone, decrease plasma LH and testosterone, or increase testosterone in hamsters and humans, it decreased serum levels of LH and testosterone in rabbits, macaques, and baboons [3]. Rekkas et al. established that testosterone in the blood of three breeds of rams showed a seasonal variation [12]. Namely, the responses to the same stress effect can change from species to species. On the other hand, chronic stress in rats, hamsters, and men has been known to have an inhibitory effect on the HPG axis through decreasing LH and testosterone [3].

It is well known that masculine sexual behavior depends mainly on testosterone, whose secretion is suppressed by stress [4, 13]. While many kinds of acute stress have been studied, chronic ones have been rarely studied. Moreover, responses to the kind of stressors changed from species to species. This situation can be explained as a rationalization or defensive mechanism for survival in the face of stressors that the test subjects have exposed themselves. For instance, in Talapoin monkeys, subordinate males (undergoing social stress) display neither an increase in aggression nor sexual behavior, as independent from their plasma LH and testosterone levels [3]. For this reason, the main purpose of our study was to identify the effect of chronic cold stress on male sexual behavior and on testosterone, FSH, LH, and prolactin levels.

According to the findings of Retana-Marquez et al., sexual behavior in male rats depends on the characteristics of each stressor and on the duration of exposure (either acute or chronic). According to their results of the immersion cold water stressor, low body temperature could be partially responsible for the low performance in sexual behavior [3]. According to our results, the frequency of the sexual thoughts and weekly ejaculations decreased in winter (Table 1). Panesar et al. showed that low temperatures slowed down metabolism, partly because the kinetic energy of molecules was reduced and enzymes might be structurally impaired. As a result, testosterone production was completely impaired [14]. In addition to these studies, Parua et al. investigated the effect of cold stress on plasma testosterone levels in toads (Bufo melanostictus) during breeding and hibernating seasons for periods of 7, 14, and 21 days. Their results revealed that cold-exposed animals displayed a decrease in testicular weight, testicular delta 5–3 beta, and 17 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase activities, as well as low levels of plasma testosterone both in breeding and hibernating seasons. There was no significant difference in terms of results after seven days of cold exposure [15].

According to our results, although the values of testosterone and FSH in winter and summer fell within normal limits, the difference between these parameters was significant statistically (Table 1). There was not any statistical difference in terms of the LH values in winter and summer. “Perhaps for that reason, the values of testosterone were within normal limits in both seasons”. According to some studies, male sexual activity increased plasma levels of both corticosterone and testosterone. This finding has been established in rats, mice, tritons, amphibians, and lizards. However, the physiological mechanism of this effect is still unknown [3]. Furthermore, sexual behavior and mating have beneficial effects on neuronal and endocrine responsiveness to stress and have an anxiolytic-like effect [16, 17]. “Namely, the sexual activity in males operates as a protective effect against the cold environment as a rationalization or defensive mechanism of nature”.

Our results revealed a statistical difference in terms of BMI results (Table 1). This result is consistent with the Retana-Marquez’s et al. study [4]. In our opinion, the mechanism of the difference with regard to BMI is associated with the suppression of appetite and feeding behavior in stressful conditions, for instance during exposure to the cold in winter. The summer may affect the appetite and feeding behavior positively. The summer diet may also affect the hormone levels and sexual behaviors. However, in contrast, there may be the effect of the hormones on metabolism such as testosterone with the different pathways. But, we believe that further randomized prospective controlled studies are needed to explain these questions and pathways.

Limitations of study

One of the limitations of our study was the lack of an acute group (exposing to the cold once but for a long time, about 8 hours). Another was that it was carried out in a single center. The third is the age range, in which a greater range until 60 years old was not included; it could obtain the comparative results in terms of the ages. Also, the summer dates chosen are usually associated with summer holidays, a fact that could influence sex behaviors (more free time, etc.) and hormones (sleeping time, outdoor activities, etc). Thus, these observations can affect our results.

CONCLUSIONS

Although testosterone levels are within normal limits in both seasons, its level in cold months is lower than the hot months. Testosterone levels can change according to the season. The impact of cold seasons in particular should be taken into account when evaluating testosterone levels and sexual status, as well as the other influences (social, cultural).

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Aquino K, Sheppard L, Watkins MB, O’Reilly J, Smith A. Social sexual behavior at work. Res Org Beh. 2014;34:217–236. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lauritsen JL, White N. Seasonal patterns in criminal victimization trends. U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics. 2014 Jun; www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/spcvt.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Retana-Marquez S, Bonilla-Jaime H, Vazquez-Palacios G, Martinez-Garcia R, Velazquez-Moctezuma J. Changes in masculine sexual behavior, corticosterone and testosterone in response to acute and chronic stress in male rats. Horm Behav. 2003;44:327–337. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2003.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Retana-Marquez S, Vigueras-Villasenor RM, Juarez Rojas L, Aragon Martinez A, Reyes Torres G. Sexual behavior attenuates the effects of chronic stress in body weight, testes, sexual accessory glands, and plasma testosterone in male rats. Horm Behav. 2014;66:766–778. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2014.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Demir A, Onol FF, Ercan F, Tarcan T. Effect of cold-induced stress on rat bladder tissue contractility and histomorphology. Neurourol Urodyn. 2007;26:296–301. doi: 10.1002/nau.20305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith RP, Coward RM, Kovac JR, Lipshultz LI. The evidence for seasonal variation of testosterone in men. Maturitas. 2013;74:208–212. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2012.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moskovic DJ, Eisenberg ML, Lipshultz LI. Seasonal fluctuations in testosterone-estrogen ratio in men from the southwest United States. J Androl. 2012;33:1298–1304. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.112.016386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stanton SJ, Mullet-Gillman OA, Huettel SA. Seasonal variation of salivary testosterone in men, normally cycling women, and women using hormonal contraceptives. Physiol Behav. 2011;104:804–808. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turek PJ. Male Reproductive Physiology. In: Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Novick AC, Partin AW, Peters CA, editors. Campbell-Walsh Urology. 10th edn. Vol. 1. Elsevier: Saunders Press; pp. 591–615. Chapt. 20. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mulligan T, Schmitt B. Testosterone for erectile failure. J Gen Intern Med. 1993;8:517–521. doi: 10.1007/BF02600118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Retana-Marquez S, Dominguez-Salazar E, Velazquez-Moctezuma J. Effect of acute and chronic stres on masculine sexual behavior in the rat. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1996;21:39–50. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(95)00029-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rekkas C, Kokolis N, Smokovitis A. Breed and seasonal variation of plasminogen activator activity and plasminogen activator inhibition in spermatozoa and seminal plasma of the ram in correlation with testosterone in the blood. Andrologia. 1993;25:101–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0272.1993.tb02690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meisel RL, Sachs BD. The physiology of male sexual behavior. In: Knobil E, Neil J, editors. The physiology of reproduction. NY: Raven Press; pp. 3–105. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Panesar NS, Chan KW. Low temperature blocks the stimulatory effect of human chorionic gonadotropin on steroidogenic acute regulatory protein mRNA and testosterone production but not cyclic adenosine monophosphate in mouse Leydig tumor cells. Metabolism. 2004;53:955–958. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parua S, Ghosh D, Nandi DK, Debnath J. Effect of cold exposure on testicular delta 5-3 beta and 17 beta hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase activities and plasma levels of testosterone in toad (Bufo melanostictus) in breeding and hibernating season: duration-dependent response. Andrologia. 1998;30:105–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0272.1998.tb01155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Waldherr M, Nyuyki K, Maloumby R, Bosch OJ, Neumann ID. Attenuation of the neuronal stres responsiveness and corticotropin releasing hormone synthesis after sexual activity in male rats. Horm Behav. 2010;57:222–229. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2009.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Justel NR, Bentosela M, Mustaca AE. Sexual behavior and anxiety. Rev Latinoam Psical. 2009;41:429–444. [Google Scholar]