Abstract

Glycosylation is an integral part in health and disease, as emphasized by the growing number of identified glycosylation defects. In humans, proteins are modified with a diverse range of glycoforms synthesized in complex biosynthetic pathways. Glycosylation disorders have been described in congenital disorders of glycosylation (CDG) as well as in acquired disease conditions such and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). A hallmark in a subset of CDG cases is the reduced glycosylation site occupancy of asparagine-linked glycans. Using an optimized method protocol, we determined the glycosylation site occupancy from four proteins of hepatic and lymphatic origin from CDG and NAFLD patients. We found variable degrees of site occupancy, depending on the tissue of origin and the disease condition. In CDG glycosylation sites of IgG2 and IgA1 were occupied to normal levels. In NAFLD haptoglobin and transferrin glycosylation sites were hyper-glycosylated, a property qualifying for its use as a potential biomarker. Furthermore, we observed, that glycosylation sites of liver-originating transferrin and haptoglobin are differentially occupied under physiological conditions, a further instance not noticed in serum proteins to date. Our findings suggest the use of serum protein hyperglycosylation as a biomarker for early stages of NAFLD.

Alcoholic liver disease (ALD), non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and congenital disorders of glycosylation (CDG) share common symptoms manifested by the development of fatty liver, liver fibrosis/cirrhosis and insulin resistance1. Whereas CDG constitutes a group of autosomal recessive inherited diseases, ALD and NAFLD are considered as acquired disease conditions2,3. Although, a recent study of twins based on MRI assessments suggests that hepatic steatosis and fibrosis are heritable traits4. NAFLD can be grouped into benign liver steatosis and the more progressed and inflammatory form of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). NAFLD/NASH is also been described as the manifestation of the metabolic syndrome in the liver1. A recent report describes NASH as a preceding determinant for the development of the metabolic syndrome with potential implications on the clinical diagnosis and treatment5. The search of biomarkers for non-invasive diagnosis, addressing the prevalence and the scope of clinical presentations is a major focus in NAFLD research6. ALD and NASH share common traits, such as the occurrence of Mallory-Denk bodies in the cytoplasm of liver cells, upregulation of the cytochrome P2E1 with subsequent increase in reactive oxygen species and accumulation of 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal in the liver tissue. The accumulation of 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal is made responsible for the development of hepatocellular carcinoma in late stage disease conditions. For the differentiation of ALD and NASH non-invasive diagnostic measures are lacking and liver biopsies are required for diagnosis7. Serum values of aminotransferases and gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase and the mean corpuscular volume of erythrocytes are overlapping between NASH and ALD samples. Nevertheless, a direct comparison of levels of carbohydrate deficient transferrin (CDT) in serum can be used to differentiate between NASH and alcoholic hepatitis patients8. N-linked glycosylation profiles have been used for diagnosing liver cirrhosis and to differentiate patients with hepatocellular carcinoma from cirrhotic patients9,10. Accordingly, an increase of a-galactosylated N-glycans with concomitant decrease of the galactosylated glycoforms serum samples, and in the Fc-region of serum IgG has been proposed as a biomarker for diagnosing advanced NASH related fibrosis and differentiating between liver steatosis and NASH11,12.

CDG is a multi-systemic condition affecting various glycosylation pathways. A new nomenclature addressing CDG forms deriving from differing glycan biosynthetic pathways was proposed, using the official gene symbol of the protein involved followed by “-CDG”13. A subset of CDG forms derived from the N-glycan biosynthesis typically display reduced glycosylation site occupancy of secreted proteins. The reduced glycosylation frequency is due to gene defects of enzymes mediating the assembly of the precursor dolichol-linked oligosaccharide or the oligosaccharide transfer to the newly synthesized glycoprotein. Other forms of CDG display aberrant glycan structures, but normal glycosylation frequency on secreted proteins, due to gene defects in proteins involved in the glycan maturation and processing in the Golgi. A common symptom to CDG and ALD is a reduced N-glycosylation site occupancy, and is characterized by an increase of CDT in the blood of affected patients14. CDT levels are routinely assessed by isoelectric focusing gel electrophoresis, HPLC analysis or liquid chromatography coupled mass spectrometry (LC-MS)15,16,17. We have previously developed a multiple reaction monitoring mass spectrometric (MRM-MS) assay to directly determine the N-glycosylation site occupancy at the peptide level, and found decreasing site occupancy in correlation with the severity of the clinical symptoms in the respective CDG forms18. Here we devised an optimized protocol, omitting immunoaffinity purification and simplified sample preparation procedures for the semi-quantitative determination of the N-glycosylation site occupancy of four serum proteins of hepatic and lymphatic tissue origin. We validated this protocol using a serum cohort from CDG patients with known hypoglycosylation phenotypes and explored its use for determining potential biomarkers for NAFLD. We selected the serum glycoproteins transferrin, haptoglobin, IgG2 and IgA1 to compare the glycosylation status of proteins derived from hepatic and lymphatic origin.

Serum IgG glycosylation has been explored in search for biomarkers for autoimmune and congenital disease conditions. Changes in the N-glycan structures at the glycosylation site in the conserved Fc-region of the IgG heavy chain have been shown to modulate the binding of IgG to Fc-gamma receptors and C-type lectins, thereby influencing the inflammatory responses in autoimmune conditions (reviewed in refs 19 and 20). In congenital defects, abnormal IgG N-glycosylation for classical galactosaemia and MAN1B1-CDG-specific IgG glycans were described recently21,22. The variable Fab-region of IgG and IgA can also contain glycosylated sequons and might have emerged via somatic hypermutation19,23. The significance of Fab-glycosylation of IgG in (patho-)physiology and immunity has been discussed recently24. IgA1 contains two N-glycosylation sites in the constant Fc region and up to six occupied O-glycosylation sites in the hinge region. GlcNAc terminating IgA1 glycans selectively bind to the transferrin receptor, mediating effector functions in IgA nephropathy. Whereas glycans terminating with galactose serve as ligands for the asialoglycoprotein receptor, mediating the clearance of IgA from the serum23. Aberrant glycosylation of IgA1 has been ascribed to result in the depositions in the glomeruli of the kidney mesangium in IgA nephropathy25.

Transferrin and haptoglobin are serum glycoproteins produced in hepatocytes. Haptoglobin contains four N-glycosylation sites and belongs to the acute phase proteins, whose blood levels and glycosylation profiles change during inflammatory reactions in sepsis, tissue damage or cancer26. Haptoglobin binds free hemoglobin for degradation in the liver and for iron recycling. The binding characteristic of haptoglobin to surface receptors of macrophages in the tumor microenvironment might play a crucial role for tumor cell growth and survival27. The iron-binding blood protein transferrin contains two N-linked glycosylation sites. Transferrin has been utilized since decades as a biomarker for monitoring alcohol abuse28. Carbohydrate deficient transferrin is characterized by a reduced N-glycosylation site occupancy or alterations in N-glycosylation profiles and is used as a versatile diagnostic marker in CDG research. Serum transferrin glycoforms are monitored by isoelectric focusing gel electrophoresis, HPLC or mass spectrometric approaches16,18,28,29.

Results

Reduced site occupancy of N-linked glycosylation sites is a hallmark in CDG and ALD. Previously, we developed a MRM-MS based method for directly determining the site occupancy at the peptide level and found decreasing occupancy in correlation with the severity of the clinical symptoms displayed in CDG with reduced N-glycosylation frequency18. Here we devised a sample preparation protocol in favor of simplicity, omitting previous glycoprotein enrichment by affinity purification. One μl of serum was reduced and alkylated before trypsin digestion, and a single sample transfer was required for isolating the tryptic peptides using a cation exchange resin. N-linked glycopeptides were enzymatically de-glycosylated with PNGase F in 18O-water containing buffer, introducing the 18O-isotope to the newly formed aspartic acid residue after deglycosylation. Isotopic labeling of the glycosylation sites helps to differentiate PNGase F reaction products from spontaneous deamination reactions of unoccupied asparagine residues. C-terminally isotope labeled standard peptides corresponding to unglycosylated and deglycosylated glycopeptide sequences were added to the samples to assess the relative N-glycosylation site occupancy. One glycosylation site per glycoprotein was assayed, based on robust detection in LC-MS-MS peptide sequencing, using the Mascot peptide score algorithm (Table 1).

Table 1. Peptides used to determine the N-glycosylation site occupancies.

| Protein | Peptide | m/z | Charge | Fragments | av. RT (min) | av. dot p | Description | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sp|P02787|TRFE_HUMAN | K.ILRQQQHLFGSNVTDCSGNFCLFR.S | 727.6059 | 4 | y4 | b132+ | b142+ | b152+ | 36.7 | 0.81 | standard-N |

| K.ILRQQQHLFGSNVTDCSGNFCLFR.S | 727.8519 | 4 | y4 | b132+ | b142+ | b152+ | 37.1 | 0.80 | standard-D | |

| K.ILRQQQHLFGSNVTDCSGNFCLFR.S | 725.3498 | 4 | y4 | b132+ | b142+ | b152+ | 37.1 | 0.76 | deamination-16O | |

| K.ILRQQQHLFGSNVTDCSGNFCLFR.S | 725.8509 | 4 | y4 | b132+ | b142+ | b152+ | 37.1 | 0.81 | deamination-18O | |

| K.ILRQQQHLFGSNVTDCSGNFCLFR.S | 725.1038 | 4 | y4 | b132+ | b142+ | b152+ | 36.7 | 0.80 | no deamination | |

| sp|P00738|HPT_HUMAN | K.VVLHPNYSQVDIGLIK.L | 601.6800 | 3 | y6 | y142+ | b9 | b102+ | 36.1 | 0.73 | standard-N |

| K.VVLHPNYSQVDIGLIK.L | 602.0080 | 3 | y6 | y142+ | b9 | b102+ | 36.5 | 0.72 | standard-D | |

| K.VVLHPNYSQVDIGLIK.L | 599.3366 | 3 | y6 | y142+ | b9 | b102+ | 36.5 | 0.67 | deamination-16O | |

| K.VVLHPNYSQVDIGLIK.L | 600.0047 | 3 | y6 | y142+ | b9 | b102+ | 36.5 | 0.88 | deamination-18O | |

| K.VVLHPNYSQVDIGLIK.L | 599.0086 | 3 | y6 | y142+ | b9 | b102+ | 36.1 | 0.73 | no deamination | |

| sp|P01876|IGHA1_HUMAN | R.LSLHRPALEDLLLGSEANLTCTLTGLR.D | 744.1571 | 4 | y10 | y11 | b11 | b122+ | 43.4 | 0.74 | standard-N |

| R.LSLHRPALEDLLLGSEANLTCTLTGLR.D | 744.4031 | 4 | y10 | y11 | b11 | b122+ | 44.2 | 0.76 | standard-D | |

| R.LSLHRPALEDLLLGSEANLTCTLTGLR.D | 741.9010 | 4 | y10 | y11 | b11 | b122+ | 44.2 | 0.63 | deamination-16O | |

| R.LSLHRPALEDLLLGSEANLTCTLTGLR.D | 742.4021 | 4 | y10 | y11 | b11 | b122+ | 44.2 | 0.71 | deamination-18O | |

| R.LSLHRPALEDLLLGSEANLTCTLTGLR.D | 741.6550 | 4 | y10 | y11 | b11 | b122+ | 43.4 | 0.70 | no deamination | |

| sp|P01859|IGHG2_HUMAN | K.TKPREEQFNSTFR.V | 825.4171 | 2 | y4 | y7 | y112+ | b9 | 28.0 | 0.75 | standard-N |

| K.TKPREEQFNSTFR.V | 825.9091 | 2 | y4 | y7 | y112+ | b9 | 28.6 | 0.81 | standard-D | |

| K.TKPREEQFNSTFR.V | 820.9050 | 2 | y4 | y7 | y112+ | b9 | 28.6 | na | deamination-16O | |

| K.TKPREEQFNSTFR.V | 821.9071 | 2 | y4 | y7 | y112+ | b9 | 28.6 | 0.86 | deamination-18O | |

| K.TKPREEQFNSTFR.V | 820.4130 | 2 | y4 | y7 | y112+ | b9 | 28.0 | na | no deamination | |

The areas of the MRM transitions corresponding to the fragment ions b132+, b142+, b152+ of the transferrin peptide, the y142+, b9, b102+ of haptoglobin peptide, the y7, b182+ of the IgA1 peptide and the y112+, y7, b9 of the IgG2 peptide were used for semi-quantitative computation of the N-glycosylation site occupancies. The deaminated asparagine residues of the N-glycosylation sequons are marked with N. The stable isotope labeled lysine and arginine residues of the standard peptides are labeled with K and R, respectively. C denotes carbamidomethylated cysteine residues. The synthetic peptides denoted with standard-N or standard-D were added to the sampled prior MRM-MS analyses. The Swiss-Prot designations for the proteins are shown. The dotp values are the similarity measures between product peak areas and the corresponding intensities in the spectral library used in Skyline. The average dotp values were calculated from manually validated MRM transitions of the peptides. The dotp values for all peptides investigated are listed in Supplemental data dotp values.xlsx. “na” = not applicable, for those peptides no product peak areas could be validated.

Testing the linearity in the peptide detection

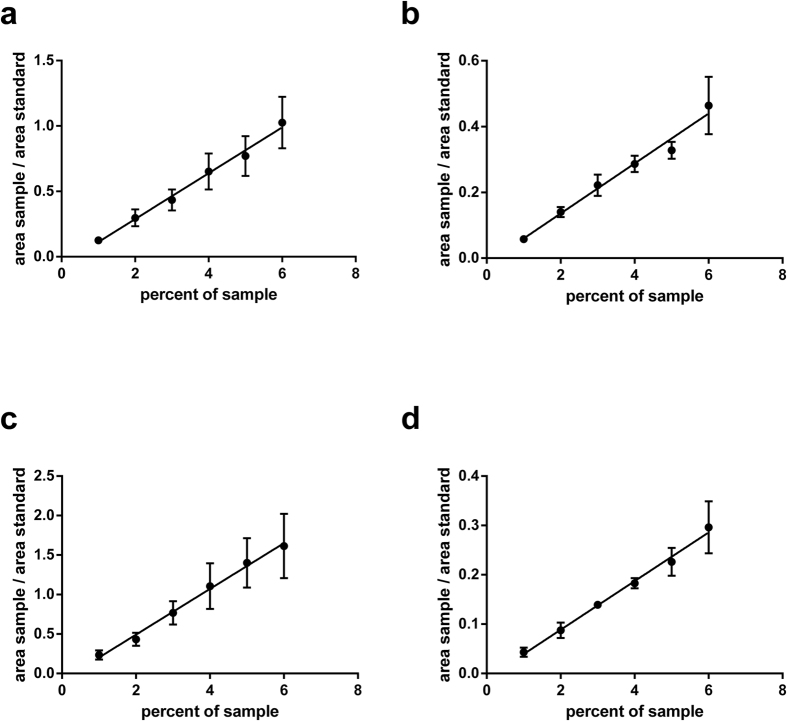

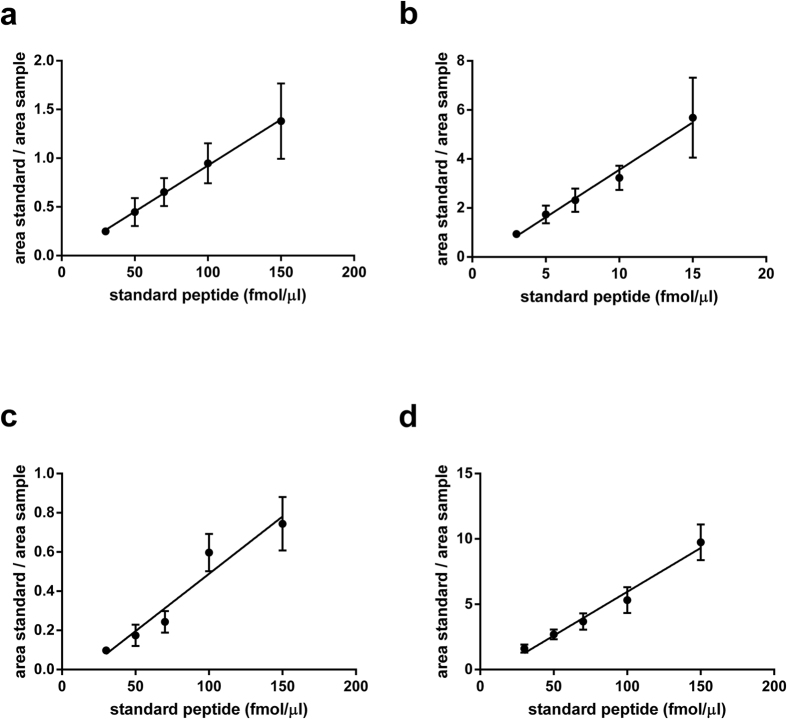

The linearity in the peptide detection was tested by loading increasing amounts of sample onto the nanobore column. We obtained a linear relationship of the amount of sample relative to the standard peptides when loading 1 to 6 percent of the sample preparation with r2 values of 0.98 and 0.99 after regression analyses (Fig. 1). Accordingly, we assayed for linearity with increasing amounts of standard peptides added to four percent of sample. We obtained a linear relationship with the standard peptides at concentrations from 25 to 150 fmol/μl for the transferrin, IgA1 and IgG2 peptides. The corresponding r2 values were calculated between 0.94 and 1.00 after regression analyses. For the haptoglobin peptides a 10-fold lower concentration was used in the standard peptide mixture, due to higher signal intensities observed for this peptide (Fig. 2). For the linearity tests technical triplicates were necessary to obtain a precise linear fit. Therefore, three replicates starting with the trypsin digests were prepared for each serum sample analyzed.

Figure 1. Linear relationship in the ratio of standard peptides with increasing amounts of sample.

Increasing amounts of the sample preparation were dissolved with the standard peptide mix and subjected to LC-MRM-MS. The areas of the sample per area of the standard peptides are plotted against the amounts of sample. Data points are displayed as mean values from triplicate sample preparations, and the error bars indicate the standard error of mean (SEM) values. Linear regression analyses was performed for the deglycosylated transferrin (a), r2 = 0.99), haptoglobin (b), r2 = 0.98), IgA1 (c), r2 = 0.99) and IgG2 peptides (d), r2 = 0.99).

Figure 2. Linear relationship of the ratio of sample derived peptides with increasing amounts of standard peptides.

Increasing concentrations of the standard peptide mix were added to the sample before subjecting to LC-MRM-MS (>70% purity, Supplemental Fig. 3). The areas of the sample per area of the standard peptides are plotted against the standard peptide concentrations. Data points are displayed as mean values from triplicate sample preparations, and the error bars indicate the standard error of mean values. Linear regression analyses was performed for the deglycosylated transferrin ((a), r2 = 1.00), haptoglobin ((b), r2 = 0.99), IgA1 ((c), r2 = 0.94) and IgG2 peptides ((d), r2 = 0.98).

Occurrence of spontaneous deamination

The occurrence of spontaneous deamination of asparagine was detected by the presence of 16O-aspartic acids in the glycosylation sequon. We observed a varying degree of deamination reactions, depending on the peptide sequence ranging from 2.9% in the haptoglobin peptide to 12.9% in IgA1 throughout all samples analyzed (Supplemental Table 2). Since the deglycosylation reaction was performed in 18O-containing buffer, 16O-aspartic acid within the sequon must have formed prior PNGase F mediated deglycosylation. Therefore, these values add towards the unglycosylated peptide count. For the IgG peptide only 18O-asparic acid could be detected, indicating that the amount of 16O-water in the reaction buffer is low and evades detection with the instrumentation used in this study (Table 2). Therefore, it appears likely that the content of 16O-water in the buffer used for the deglycosylation reaction did not contribute significantly to the 16O-aspartic acid counts.

Table 2. N-glycosylation site occupancies in health and liver disease conditions.

| ID | Sample | OMIM entry | Clinical score | TRFE |

HPT |

IGHA1 |

IGHG2 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean | SEM | mean | SEM | mean | SEM | mean | SEM | ||||

| 001 | PMM2-CDG | 601785 | * | 86 | 2.8 | 3 | 1.0 | 82 | 2.8 | 100 | 0.0 |

| 002 | PMM2-CDG | 601785 | mild | 90 | 2.1 | 32 | 4.6 | 83 | 1.0 | 100 | 0.0 |

| 003 | PMM2-CDG | 601785 | mild/moderate | 91 | 0.7 | 24 | 3.1 | 86 | 1.0 | 100 | 0.0 |

| 004 | PMM2-CDG | 601785 | moderate | 91 | 1.0 | 13 | 2.2 | 87 | 0.2 | 100 | 0.0 |

| 005 | PMM2-CDG | 601785 | severe | 84 | 1.8 | 3 | 0.5 | 86 | 2.1 | 100 | 0.0 |

| 034 | AlG11-CDG | 613661 | * | 94 | 0.1 | 28 | 1.2 | 90 | 2.7 | 100 | 0.0 |

| 036 | AlLG1-CDG | 608540 | moderate | 82 | 2.1 | 7 | 0.4 | 91 | 0.1 | 100 | 0.0 |

| 037 | ALG6-CDG | 603147 | severe | 85 | 0.5 | 3 | 0.3 | 90 | 0.5 | 100 | 0.0 |

| 038 | MPDU1-CDG | 604041 | moderate/severe | 91 | 0.5 | 12 | 3.4 | 87 | 1.7 | 100 | 0.0 |

| 039 | RFT1-CDG | 612015 | severe | 72 | 1.7 | 3 | 0.7 | 91 | 1.8 | 100 | 0.0 |

| 007 | healthy | na | na | 93 | 0.9 | 61 | 2.5 | 84 | 1.8 | 100 | 0.0 |

| 008 | healthy | na | na | 94 | 0.5 | 57 | 3.2 | 86 | 1.6 | 100 | 0.0 |

| 009 | healthy | na | na | 93 | 1.1 | 54 | 1.8 | 85 | 1.3 | 100 | 0.0 |

| 010 | healthy | na | na | 95 | 0.5 | 52 | 3.1 | 84 | 1.3 | 100 | 0.0 |

| 011 | healthy | na | na | 95 | 0.5 | 56 | 6.5 | 86 | 4.3 | 100 | 0.0 |

| 012 | Steatosis | nd | <3 | 95 | 1.4 | 73 | 4.0 | 86 | 1.9 | 100 | 0.0 |

| 013 | Steatosis | nd | <3 | 94 | 0.5 | 71 | 5.6 | 85 | 1.0 | 100 | 0.0 |

| 015 | Steatosis | nd | <3 | 95 | 0.7 | 61 | 5.8 | 84 | 4.0 | 100 | 0.0 |

| 016 | Steatosis | nd | <3 | 95 | 0.5 | 68 | 1.9 | 87 | 1.4 | 100 | 0.0 |

| 014 | NASH | nd | 5 | 95 | 0.2 | 69 | 1.9 | 86 | 1.5 | 100 | 0.0 |

| 017 | NASH | nd | 3 | 95 | 0.8 | 59 | 5.2 | 86 | 0.9 | 100 | 0.0 |

| 018 | NASH | nd | 4 | 96 | 1.0 | 64 | 1.4 | 86 | 1.9 | 100 | 0.0 |

| 019 | NASH | nd | 5–6 | 95 | 0.7 | 69 | 4.1 | 82 | 1.4 | 100 | 0.0 |

| 020 | NASH | nd | 4 | 95 | 1.5 | 60 | 12.3 | 88 | 2.6 | 100 | 0.0 |

| 021 | NASH | nd | 4 | 94 | 0.7 | 53 | 4.4 | 88 | 3.3 | 100 | 0.0 |

| 022 | NASH | nd | 6 | 95 | 1.3 | 43 | 3.9 | 91 | 1.5 | 100 | 0.0 |

| 023 | NASH | nd | * | 94 | 0.7 | 58 | 11.5 | 90 | 2.0 | 100 | 0.0 |

The values for each glycosylation site are averaged from three technical replicates, starting with the serum sample preparation. SEM = standard error of mean. Average values derived from 5 samples from healthy serum, 4 liver steatosis samples and 8 NASH samples. OMIM = Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man, na = not applicable, nd = not determined, ID = unique sample identifier, TRFE = transferrin, HPT = haptoglobin, IGHA1 = human IgA1, IGHG2 = human IgG2, (*) = no clinical information available. The clinical score values are displayed according to Grünewald et al. or Kleiner et al. (NAFLD activity scores), respectively30,31.

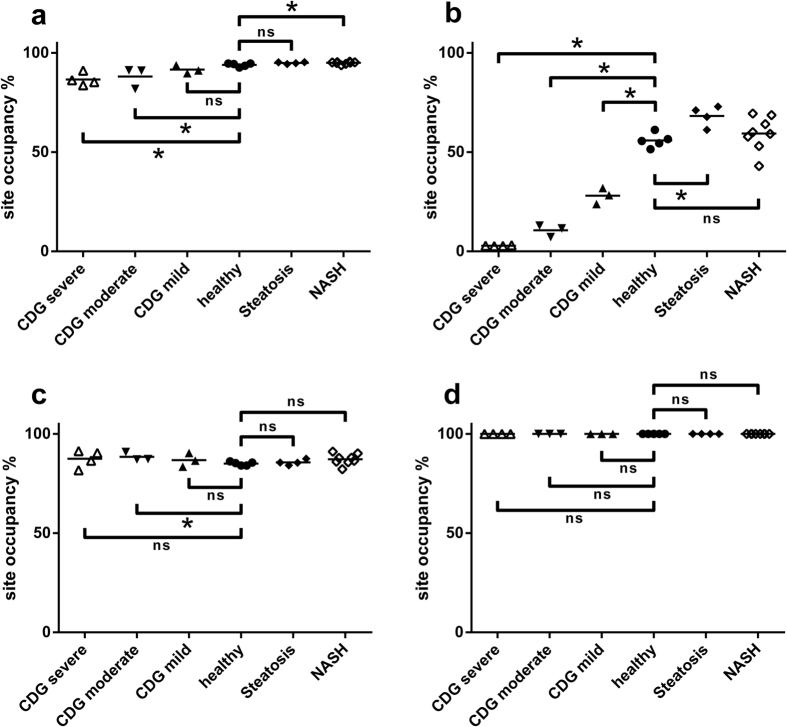

Serum samples

Cohorts of 10 CDG and 12 NAFLD with varying severities of clinical symptoms were selected to assay the N-glycosylation site occupancies. The CDG samples were collected from patients with mild, moderate and severe symptoms according to the scoring system proposed by Grünewald et al.30. The CDG samples selected comprised defects in the biosynthesis upstream to the transfer of the preassembled oligosaccharide precursor to the newly synthesized protein (i.e. PMM2-CDG, ALG11-CDG, ALG1-CDG, ALG6-CDG, MPDU1-CDG, RFT1-CDG, see Table 2). These CDGs are characterized by a reduced N-glycosylation site occupancy in serum proteins such as the diagnostic marker protein transferrin. The liver disease samples were obtained from patients with NAFLD activity scores ranging from less than 3 to 6 (Table 2)31. Reduced N-glycosylation site occupancies were observed for the CDG samples with liver synthesized transferrin and haptoglobin, whereas no change in glycosylation frequency was observed with the glycopeptides from the immunoglobulins IgA1 and IgG2. It stands out, that under physiological conditions N-glycosylation sites are differentially glycosylated, depending on the glycoprotein. This is evident when comparing the transferrin and haptoglobin glycopeptides (Fig. 3). Both proteins are mainly synthesized in hepatocytes. Typically, transferrin contains two and haptoglobin contains four N-linked glycosylation sites. A third N-linked glycosylation site has been described at a non-canonical NXC sequon within the human transferrin at Asn491. This glycosylation site has been described to be occupied at 2 mol% in a commercially available human transferrin preparation and is not always detectable in serum protein preparations32,33. Whereas the transferrin peptide is almost completely glycosylated in healthy individuals, only 56% of the haptoglobin peptide at Asn241 is glycosylated on average. Likewise, the IgG2 peptide is completely glycosylated and the IgA1 glycopeptide is glycosylated to 85% in healthy control sera. The glycosylation sites tested to date were occupied to nearly 100% in healthy control serum samples18. The observation of differential degrees of glycosylation, depending on the glycoprotein is unprecedented and appears to be a tissue-independent cellular phenomenon.

Figure 3. N-glycosylation site occupancy in CDG and NAFLD.

The site occupancy in % of the transferrin (a), haptoglobin (b), IgA1 (c) and IgG2 (d) glycopeptides is plotted for the CDG, NAFLD and healthy control samples. Each data point represents the mean value of triplicate measurements starting with the sample preparation. The biological mean values with error bars (SEM) are indicated in each group of serum samples plotted. Differences between groups were calculated using the Mann-Whitney statistical test. Differences were considered significant with p < 0.05 (*). ns = non-significant. The CDG samples were obtained from PMM2-CDG, ALG11-CDG, ALG1-CDG, ALG6-CDG, MPDU1-CDG and RFT1-CDG patients, and grouped into severe, moderate and mild phenotypes. The NAFLD group is divided into liver steatosis and NASH samples.

CDG and NAFLD

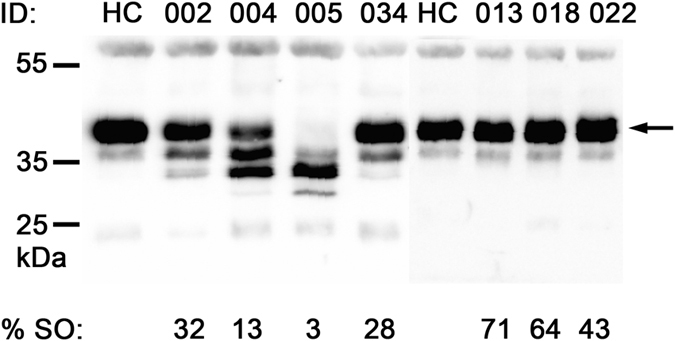

In CDG the extent of hypoglycosylation of haptoglobin can reach to as low as 3% site occupancy as seen in CDG samples with a severe clinical display (PMM2-CDG, Alg6-CDG, RFT1-CDG, Table 2), whereas for the transferrin glycosylation site the lowest value measured was 72% (RFT1-CDG, Table 2), highlighting the dynamic range of N-glycosylation site occupancies for serum glycoproteins. Reduced site occupancy for the IgA1 and IgG2 glycopeptides could not be observed in any of the CDG or NAFLD samples analyzed in this study (Fig. 3C,D). On the other hand, for the transferrin and haptoglobin glycopeptides of the NAFLD samples an increased glycosylation frequency was detected. The increase observed with the transferrin peptide corresponds to a mean value of 94 raised to 96% site occupancy (NASH group, Fig. 3A). Although the difference is minimal, a p-value of 0.026 was calculated after statistical evaluation, using the Mann-Whitney-test. An increased glycosylation within the steatosis samples was pronounced when analyzing the haptoglobin glycopeptide (Fig. 3B). The average site occupancy rose from 56 to 68%, compared to the healthy control samples. Hyperglycosylation appears to occur early during the development of liver steatosis in NAFLD. An increase in site occupancy was observed in the steatosis samples, whereas the site occupancy of the haptoglobin peptide in the NASH samples is heterogeneous, varying from mildly hypo- to hyperglycosylation. On the other hand, statistical comparison among the diseased groups did not yield significance in the difference neither between severe versus moderate or moderate versus mild CDG nor between the steatosis and NASH group (Supplemental Table 3).The variability in the NASH samples reflects the heterogeneity within this NAFLD classification. Notably, for the sample with the lowest site occupancy in the NASH group, a differential diagnosis was indicated for viral hepatitis (ID 022, Table 3). This patient with an NAS score of 6 also displayed the most advanced fibrosis stage. In contrast, patient 019 has a similar NAS score, but displayed only a mild fibrosis stage. It remains to be shown to what extent a reduced N-glycosylation site occupancy correlates with the formation of liver fibrosis. The hyperglycosylation phenotype of haptoglobin in NAFLD sera was not visible in Western blot analyses (Fig. 4, Supplemental Fig. 2). Possibly, the increase in mass due to additional N-glycosylation is not resolved during SDS-PAGE. The gain in mass of hyperglycosylated haptoglobin may be insufficient to result in a significant shift in the protein migration that can be resolved within in the mass range of haptoglobin. On the other hand, hypoglycosylation of haptoglobin is clearly resolved in CDG samples. In agreement with earlier findings, the degree of underglycosylation of haptoglobin correlates with the severity of the clinical CDG manifestations18 Likewise, with isoelectric focusing gel electrophoreses the CDG samples were clearly recognized, whereas the NAFLD samples were without pathological findings (Supplemental Fig. 1).

Table 3. NAFLD clinical data.

| ID | Sample | Clinical score | Age | Gender | Steatosis level | Hepatocyte ballooning | Inflammation | Fibrose stage | Differential diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 012 | Steatosis | <3 | 53 | f | mixed vesicular | isolated ballooning | borderline to steatohepatitis | Fibrose stage 2 | |

| 013 | Steatosis | <3 | 40 | m | mixed vesicular | no ballooning | some portal inflammation | none | |

| 015 | Steatosis | <3 | 34 | m | mixed vesicular | no ballooning reported | none | focal pericellular fibrosis | |

| 016 | Steatosis | <3 | 40 | f | mainly micovesicular | no ballooning | none | minor pericellular fibrosis | nutritional or medicinal intoxication |

| 014 | NASH | 5 | 40 | m | mixed vesicular | ballooning | minor lobular inflammation | isolated minor pericellular fibrosis | |

| 017 | NASH | 3 | 52 | m | moderate mixed vesicular | isolated ballooning | no lobular or portal inflammation | no portal or pericellular fibrosis | |

| 018 | NASH | 4 | 50 | f | moderate mainly macrovesicular | discreet ballooning | sparse mixed cellular inflammarory portal infiltration | discreet pericentral fibrosis and perisinusoidal collagen deposition | |

| 019 | NASH | 5–6 | 54 | f | mainly macrovesicular | ballooning | isolated, sparse portal inflammatory infiltration | discreet focal pericellular fibrosis | |

| 020 | NASH | 4 | 54 | f | mixed vesicular | pronounced ballooning | focal necro-inflammatory activity | perisinusoidal, portal and periportal fibrosis, focal septum formation | |

| 021 | NASH | 4 | 31 | m | mixed vesicular | isolated ballooning | no lobular or portal inflammation | minor pericellular fibrosis | |

| 022 | NASH | 6 | 58 | m | mixed vesicular | ballooning | portal and lobular inflammation | septal and portal fibrosis | additional viral hepatitis appears to be possible |

| 023 | NASH | * | 66 | f | mainly macrovesicular | ballooning | no definite florid lobular inflammation | minor focal pericellular fibrosis |

ID = unique sample identifier, the clinical score values are displayed as NAFLD activity scores31.

Figure 4. Western-blot analyses of haptoglobin from CDG and NAFLD samples.

Lanes with ID 002-005 show CDG samples with increasing severity of the clinical symptoms; ID 002, PMM2-CDG, mild, ID 004, PMM2-CDG, moderate, ID 005, PMM2-CDG, severe30. ID 034 shows the ALG11-CDG sample and lanes with ID 013-022 show NAFLD samples with increasing clinical scores; ID 013, steatosis, score < 3, ID 018, NASH, score 4, ID 022, NASH, score 631. The arrow indicates the migration position of fully glycosylated haptoglobin. The migration positions of the protein molecular weight markers are indicated at the left in kDa. The percent site occupancy of the corresponding haptoglobin glycopeptide is indicated below the lanes (% SO = percent site occupancy, ID = unique sample identifier, HC = pooled healthy control serum).

Discussion

In this pilot study, we analyzed the N-glycosylation sites from liver derived glycoproteins and glycoproteins of lymphatic origin, using sample cohorts from CDG and NAFLD patients together with healthy control sera. Using an optimized sample preparation protocol, four glycoproteins, haptoglobin, transferrin, IgG2 and IgA1 were analyzed. Our results show that in comparison to healthy controls, haptoglobin is hyperglycosylated in liver steatosis patients, suggesting hyperglycosylation as a diagnostic marker for early stage NAFLD. Furthermore, we show that IgG2 and IgA1 of CDG patients are normally glycosylated. We found that serum glycoproteins are glycosylated to varying degrees under physiological conditions, an instance not noticed in serum proteins to date.

Increased levels of CDT are a common hallmark in ALD and CDG, and the absence of entire glycan chains in CDT has been shown18,29. Here we provide direct evidence that IgA1 and IgG2 glycosylation levels are not affected in CDG patients with a hypoglycosylation phenotype of serum transferrin and haptoglobin. Whereas for the IgG2 peptide no unglycosylated sequon could be detected, the glycosylation level of IgA1was determined to average at 82 to 90% site occupancy. The normal glycosylation levels of the immunoglobulins in CDG point to compensatory or alternative biosynthetic processes in lymphatic tissues yielding homeostatic N-glycosylation levels. Another explanation for this observation may be a rapid clearance of unglycosylated immunoglobulins in the blood via an as yet unknown processes analogous to the asialoglycoprotein receptor mediated clearance of IgA from the serum23. Glycosylation of the Fc-region is important for mediating the effector functions via binding to the Fc-receptors to regulate immune responses20. De-sialylated, galactose exposing glycoproteins are recognized by the hepatic asialoglycoprotein receptor and rapidly cleared from the blood circulation34. The presence of high mannose N-glycan accelerates the clearance rate of IgG through binding to the mannose receptor present on immune cells in mice35. Complete absence of Fc region glycosylation however results in the loss of effector functions in vivo as well as decreased stability and increased protein aggregation in vitro, which might explain the observed absence of unglycosylated IgG in the serum samples analyzed in this study20,36. Our observations that the liver derived transferrin and haptoglobin glycopeptides are hypoglycosylated, and the immunoglobulins are not affected in the CDG cases analyzed, are in good agreement with findings described by Dupre et al.37. In Western blot analyses of IgG from serum and peripheral blood mononuclear cell homogenates as well as of the glucose transporter GLUT-1 in skin fibroblast homogenate, no indications for underglycosylation in PMM2-CDG samples were detected. Based on their findings with further glycoproteins in different cell types, the authors concluded that hypoglycosylation of proteins is tissue dependent in PMM2-CDG.

Previously, we found a preferential glycosylation of the first N-linked glycosylation sites and a higher susceptibility of the second site to hypoglycosylation in transferrin and α1-antitrypsin. Hypoglycosylation was found to correlate with the severity of the clinical symptoms in CDG. Furthermore, the level of hypoglycosylation detected in transferrin of the patient samples reached as low as 41% for the most severe CDG cases18. Here we selected one glycosylation site per protein based on the detectability in LC-MS after proteolytic digestion with a single protease. The serum samples were prepared with minimal sample manipulations, omitting immunoaffinity purification of the proteins. CDG samples with various gene defects were selected to validate the sample preparation protocol. In this study, the lowest detected glycosylation site occupancy of the corresponding transferrin peptides was found to be 72% for equally severe diseased patients. The greater range in hypoglycosylation observed with the previous method is of advantage for assessing the severity of the clinical phenotype using transferrin as the diagnostic marker, and can be explained by an enrichment-bias towards unglycosylated transferrin epitopes induced by the immunoaffinity purification18. Therefore, the values obtained in this study most likely present a more precise description of the samples analyzed, since a bias in the sample preparation due to immunoaffinity enrichment was precluded. We found a dramatic dynamic range of hypoglycosylation with the haptoglobin peptide. In the healthy control samples the haptoglobin peptide is glycosylated to 56% only, a value so far not observed in proteins in non-diseased conditions. This finding is in contrast to previous reports showing a 95% N-glycosylation site occupancy for hemoglobin-affinity enriched haptoglobin38. It is conceivable, that the affinity enrichment introduces a bias towards glycosylated haptoglobin. Whether haptoglobin binding to free hemoglobin in vivo is affected by the glycosylation status of the carrier protein is not clear. The physiological significance of haptoglobin N-glycosylation site occupancies remain to be demonstrated. Nevertheless, haptoglobin appears to be more adequate for detecting changes in glycosylation frequency than other serum proteins examined to date. Haptoglobin glycosylation has been investigated in previous studies, comparing hepatocellular carcinoma patients originated from ALD, hepatitis C and hepatitis B virus infection. Quantitative analysis of purified haptoglobin N-glycans indicated an increase in bi-fucosylated glycans in hepatocellular carcinoma patients, providing a potential use as a marker for the detection of early stage hepatocellular carcinoma patients39. In these studies however, the glycosylation site occupancy has not been addressed. A comprehensive assessment of the haptoglobin glycosylation status from differing liver disease conditions might be valuable for identifying predictive liver disease markers in future studies.

The N-glycosylation site occupancy of serum proteins has not been determined in NAFLD patients in previous studies. Originally, reduced glycosylation was observed in ALD and the determination of CDT levels are used as a reliable means to monitor disease progression and patient compliance28. The cytochrome CytP2E1 is upregulated in ALD and NASH, and made responsible for the increased production of reactive oxygen species in the corresponding tissue40. In this regard it is surprising to find opposing glycosylation levels in NAFLD and ALD patients, indicating that the regulation of N-glycosylation site occupancy is independent of CytP2E1 mediated oxidative stress. In search for diagnostic markers to differentiate alcoholic hepatitis from NASH, Ohtsuka et al.8 found increasing levels of CDT in alcoholic hepatitis patients in comparison to patients with NASH. The relationship of patient to healthy control samples, however has not been investigated, leaving questions about the levels of CDT in NASH unanswered. Alterations in the N-glycosylation site occupancy are a result of interferences in the biosynthesis upstream to the transfer of glycan precursors to the newly synthesized polypeptide in the ER, whereas alterations in the N-glycans structures can be attributed to interferences in the glycan maturation and processing in the Golgi. Deficient glycan processing enzymes or defective Golgi associated proteins can be involved in this instance. Here we determined a clear hyperglycosylation of the haptoglobin peptide in sera obtained from liver steatosis patients. The hyperglycosylation of haptoglobin occurred independent of liver inflammation, prior to the development of NASH in the early staged NAFLD patients. The observed occurrence of hyperglycosylation in NAFLD might be a result of interferences early in the biosynthesis of the N-glycans. On the other hand, increases in site occupancy will most likely affect the N-glycan maturation, due to an increased load of substrate for the Golgi localized glycan processing enzymes. For instance, the undergalactosylation of serum N-glycans was proposed as a glycomarker for liver inflammation and NASH-related fibrosis11,12. In subsequent studies, increased fucosylation of haptoglobin N-glycans as a diagnostic marker for NASH were suggested41,42. In this context, analyzing the glycosylation site occupancy provides a sensitive and specific means to diagnose liver steatosis early in NAFLD before the development of NASH.

In conclusion our data suggest that under physiological conditions N-glycosylation sites can be occupied with different frequencies, depending on the glycoprotein, an instance as yet not described in serum proteins. For the glycoproteins investigated, glycosylation site occupancies were also dependent on the tissue of origin. Furthermore, no changes to healthy controls were observed with the immunoglobulin derived peptides in the CDG patients. Our third finding that in NAFLD haptoglobin is hyperglycosylated opens new opportunities in biomarker research for fatty liver diseases.

Methods

Serum Samples

Ten CDG samples obtained from patients with confirmed diagnosis of PMM2-CDG, Alg11CDG, Alg1-CDG, Alg6-CDG, MPDU1-CDG and RFT1-CDG and 5 healthy control samples were used. Twelve NAFLD samples, 4 with confirmed diagnosis of steatosis and 8 samples with confirmed diagnosis of NASH were evaluated. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University Hospital Zurich and all NAFLD patients were provided with written, informed consent. All experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines and regulations of the Ethics Committee of the University Hospital Zurich.

Preparation of serum samples

One μl of serum was diluted 20-fold to give 20 μl of 50 mM triethylammonium bicarbonate buffer (Sigma, Switzerland), pH 8.5, 0.1% (w/v) SDS, 5 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (ThermoFischer, USA) and incubated for one hour at 60 °C. The samples were cooled to room temperature, 10 μl of freshly prepared 50 mM iodoacetamide were added and the samples were incubated at room temperature in the dark. After 40 min, a five-fold excess of dithiothreitol over iodoacetamide was added to quench the reaction and the samples were digested with trypsin for 16 h at 37 °C (10 μl of 0.5 μg trypsin/μl in H2O, sequencing grade, Roche, Switzerland). The samples were acidified with 4 μl of 10% (v/v) acetic acid and stored at −20 °C until further processing. A 0.5 ml Dowex AG50 × 8 column was pre-cycled with 5% (v/v) ammonia in 25% (v/v) acetonitrile and equilibrated with 0.8% (v/v) acetic acid in 25% (v/v) acetonitrile. The samples were diluted to 8 ml with 0.8% (v/v) acetic acid, 25% (v/v) acetonitrile, loaded onto the column, washed with 6 ml of 0.8% (v/v) acetic acid, 25% (v/v) acetonitrile and eluted with 2 ml 5% (v/v) ammonia, 25% (v/v) acetonitrile. The volumes of the eluates were concentrated by rotary evaporation before lyophilization. The dried samples were re-dissolved in 44 μl 20 mM ammonium bicarbonate buffer prepared with 18O-H2O (>97% 18O, Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, USA) and 6 units of N-glycosidase F (Roche, Switzerland) in 20 mM 18O-H2O ammonium bicarbonate buffer were added. The peptides were de-glycosylated for 6 h at 37 °C and aliquots were desalted with ZipTip C18 tips (Millipore, USA) prior submission to mass spectrometry.

A standard peptide mix consisting of synthetic peptides with c-terminal labeled arginine or lysine corresponding to the target glycopeptide sequences with asparagine or aspartic acid at the glycosylation sites was prepared (>70% purity, Intavis AG, Germany, Table 1, Supplemental Fig. 3). The peptides were dissolved in 2% (v/v) acetonitrile, 0.1% (v/v) formic acid at a concentration of 100 or 50 fmol per μl for the transferrin, IgG2 and IgA1 peptides and 10 or 5 fmol per μl for the haptoglobin peptides. An aliquot corresponding to 4% of the sample was desalted with ZipTip C18 tips, dried by rotary evaporation, and re-dissolved in 10 μl of the standard peptide mix. For each sample, 4 μl were injected onto a nano-frit column (15 cm × 75 μm; OD 375 μm; beads, Magic C18 AQ, 3 μm, 200 Å; Bischoff Chromatography, Germany), connected to a spray tip (PicoTip emitter, New Objective, USA), coupled to an Eksigent nano LC system (Eksigent, AB Sciex, USA). The column was kept at 50 °C. Peptides were eluted using a gradient from 3 to 45% acetonitrile, 0.1% (v/v) formic acid in water for 40 min, and a flow rate of 300 nl/min.

LC-MS-MS peptide sequencing

Glycosylation site containing peptides were identified by LC-MS-MS peptide sequencing. The dried peptides were re-suspended in 3% (v/v) acetonitrile and 0.1% (v/v) formic acid and analyzed on a LTQ-Orbitrap Velos mass spectrometer (ThermoFischer Scientific, USA) coupled to an Eksigent nano LC system (Eksigent, AB Sciex, USA). The analyses were performed in the data-dependent acquisition mode. The ten most intense precursor ions in the mass range m/z 300–2000 were selected for HCD spectrum acquisition with a normalized collision energy of 40 V. Single charged precursors and unassigned charge states were rejected and the minimal signal intensity required for MS2 was 2000 counts. Dynamic exclusion was switched on with an exclusion list size of 50, and an exclusion mass width relative to mass of ±10 ppm. Values were excluded from MS/MS for 45 s. The instrument was calibrated externally according to the manufacturer’s instructions. From the LC-MS-MS peptide sequencing results of a healthy control serum, treated with PNGase F in 18O-H2O buffer, a spectral library was generated and imported into Skyline for the MRM-method development. The glycopeptides were selected on the basis of robust detection after identification using the Mascot search engine (Matrix Science, UK; Version: 2.4.1.). Mascot was set up to search the human protein entries of the Swissprot database (downloaded 04.12.2012, 170103 entries, containing decoy dataset and common contaminants) assuming the digestion enzyme trypsin with maximal one missed cleavage. Mascot was searched with a fragment ion mass tolerance of 0.60 Da and a parent ion tolerance of 10.0 ppm. Carbamidomethyl-alkylation of cysteine was specified as fixed modifications. Oxidation of Met, Gln conversion to pyro-Glu and 18O-incorporation in Asn residues were specified in Mascot as variable modifications. Suitable tryptic peptides were selected on the basis of high peptide identification scores for the synthesis of isotopically labeled standards. Selected peptides should not contain missed cleavage sites or methionine whenever possible. The peptide length was kept short with maximal one missed tryptic cleavage site to enable reproducible and unambiguous identifications and chromatographic separation of deaminated and non-deaminated peptide variants.

MRM-method development

Four glycosylation site containing peptides were selected from four proteins, based on robust detection in LC-MS-MS peptide sequencing. Theoretical MRM transitions were computed using the Skyline software environment, and six transition per precursor were analyzed43. LC-MRM-MS files were imported and precursor-fragment transitions were manually inspected for correct assignment and accurate peak integration. Precursor peaks were identified by co-elution of transitions derived from the isotopically labeled standard peptides included in the samples. The four transitions showing most intense signals and highest selectivity for each precursor in comparison to the spectral library were selected. Whenever possible, transitions including the glycosylation site in the fragment ion were selected. For the four selected peptides a list was assembled of 104 transitions (Supplemental Table 1). The isotopically labeled standard peptide mix was used to validate the transitions and to empirically optimize collisional energies (Table 1).

The analyses were performed in positive ion mode on a QTRAP 5500 mass spectrometer (AB Sciex, USA) equipped with a nanospray ion source. The interface temperature was set to 170 °C, an ion spray voltage from 2000–2500 V, the ion source gas pressure was 6–10 psi, the curtain gas pressure was 25 psi, and the collision gas set to medium was used. The declustering potential had a value of 80 V, collision cell exit potential of 13 V, and entrance potential of 10 V. Further settings were unit resolution for both Q1 and Q3 and 3 ms pause between mass ranges. The total scan time was 2.6 s.

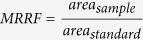

For quantitative calculations of peptide abundances only transitions unique to the target peptide were used (Table 1). The product peak areas were validated manually and assessed for the co-elution of the sample peptides with the isotope labeled standard peptides added to the samples. Molar relative response factors (MRRF) were computed for spontaneously deaminated peptides (i.e. deamination-16O, not glycosylated, MRRF-16O), enzymatically deaminated peptides (i.e. deamination-18O, deglycosylated, MRRF-18O) and non-deaminated peptides (i.e. not glycosylated, MRRF-N):

|

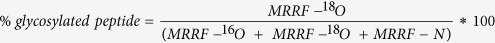

The relative glycosylation site occupancy was calculated using the MRRF:

|

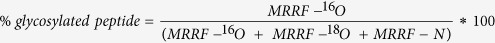

The portion of spontaneously deaminated peptides was calculates as follows.

|

Western blot analysis of serum haptoglobin

Serum samples were diluted 1:250 in H2O and serum protein precipitated by the addition of 1/10 volume 100% (w/v) trichloroacetic acid (w/vol). Precipitated protein was centrifuged, protein pellets washed with ice-cold acetone and dried at 95 °C for 10 min. For SDS-PAGE, dried pellets were dissolved in 200 μl 2x Laemmli Sample Buffer containing 5% (v/v) 2-mercaptoethanol and boiled for 5 min at 95 °C. Proteins were separated on a 10% (w/v) SDS polyacrylamide gel and blotted onto Protran BA85 nitrocellulose membrane (Whatman) and blocked at room temperature for 1 h in PBS-0.1% (v/v) Tween −5% (w/v) non-fat dry milk (PBSTP). The membrane was incubated for 1 h at room temperature with 1/3500 rabbit-α-human haptoglobin (DakoCytomation), followed by incubation with 1/5000 goat-α-rabbit –HRPO (Santa Cruz). All incubation steps were performed in PBSTP and the membrane was subsequently washed three times in PBS −0.1% Tween. Detection occurred using ECL (GE Healthcare Life Sciences).

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Hülsmeier, A. J. et al. Glycosylation site occupancy in health, congenital disorder of glycosylation and fatty liver disease. Sci. Rep. 6, 33927; doi: 10.1038/srep33927 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Prof. Jaak Jaeken, Centre of Metabolic Disease, University Hospital Gasthuisberg, Leuven, Belgium for providing CDG serum samples.We thank Dr. Oliver Tschopp, Divisions of Endocrinology, Department of Internal Medicine, University Hospital Zurich, for providing the NAFLD serum samples. We thank Dr. Asa Wahlander and Dr. Nathalie Selevsek, Functional Genomics Center Zurich, for their excellent support with the mass spectrometers. This work was supported by the University of Zurich.

Footnotes

Author Contributions A.J.H. designed and performed the experiments, analyzed the results and wrote the manuscript. M.T. performed western blot experiments, isoelectric focusing gel electrophoresis and analyzed results. P.B. and T.H. wrote the manuscript.

References

- Neuman M. G. et al. Alcoholic and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Exp Mol Pathol 97, 492–510, doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2014.09.005 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altamirano J. & Bataller R. Alcoholic liver disease: pathogenesis and new targets for therapy. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 8, 491–501, doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2011.134 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. C., Horton J. D. & Hobbs H. H. Human fatty liver disease: old questions and new insights. Science 332, 1519–1523, doi: 10.1126/science.1204265 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loomba R. et al. Heritability of Hepatic Fibrosis and Steatosis Based on a Prospective Twin Study. Gastroenterology 149, 1784–1793, doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.08.011 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonardo A., Ballestri S., Marchesini G., Angulo P. & Loria P. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a precursor of the metabolic syndrome. Dig Liver Dis 47, 181–190, doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2014.09.020 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick E. & Dhawan A. Noninvasive biomarkers in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: current status and a glimpse of the future. World J Gastroenterol 20, 10851–10863, doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i31.10851 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spengler E. K. & Loomba R. Recommendations for Diagnosis, Referral for Liver Biopsy, and Treatment of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Mayo Clin Proc 90, 1233–1246, doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.06.013 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtsuka T., Tsutsumi M., Fukumura A., Tsuchishima M. & Takase S. Use of serum carbohydrate-deficient transferrin values to exclude alcoholic hepatitis from non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: a pilot study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 29, 236S–239S (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callewaert N. et al. Noninvasive diagnosis of liver cirrhosis using DNA sequencer-based total serum protein glycomics. Nat Med 10, 429–434 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X. E. et al. N-glycomic changes in hepatocellular carcinoma patients with liver cirrhosis induced by hepatitis B virus. Hepatology 46, 1426–1435, doi: 10.1002/hep.21855 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blomme B. et al. N-glycan based biomarker distinguishing non-alcoholic steatohepatitis from steatosis independently of fibrosis. Dig Liver Dis 44, 315–322, doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2011.10.015 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C. et al. Serum protein N-glycans profiling for the discovery of potential biomarkers for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. J Proteome Res 8, 463–470, doi: 10.1021/pr800656e (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeken J., Hennet T., Matthijs G. & Freeze H. H. CDG nomenclature: time for a change! Biochimica et biophysica acta 1792, 825–826, doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2009.08.005 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arndt T. Carbohydrate-deficient transferrin as a marker of chronic alcohol abuse: a critical review of preanalysis, analysis, and interpretation. Clinical chemistry 47, 13–27 (2001). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bean P. & Peter J. B. Allelic D variants of transferrin in evaluation of alcohol abuse: differential diagnosis by isoelectric focusing-immunoblotting-laser densitometry. Clinical chemistry 40, 2078–2083 (1994). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helander A., Bergstrom J. & Freeze H. H. Testing for congenital disorders of glycosylation by HPLC measurement of serum transferrin glycoforms. Clinical chemistry 50, 954–958, doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2003.029629 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacey J. M., Bergen H. R., Magera M. J., Naylor S. & O’Brien J. F. Rapid determination of transferrin isoforms by immunoaffinity liquid chromatography and electrospray mass spectrometry. Clinical chemistry 47, 513–518 (2001). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hülsmeier A. J., Paesold-Burda P. & Hennet T. N-glycosylation site occupancy in serum glycoproteins using multiple reaction monitoring liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. Mol Cell Proteomics 6, 2132–2138, doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700361-MCP200 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plomp R., Bondt A., de Haan N., Rombouts Y. & Wuhrer M. Recent advances in clinical glycoproteomics of immunoglobulins. Mol Cell Proteomics, doi: 10.1074/mcp.O116.058503 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony R. M. & Ravetch J. V. A novel role for the IgG Fc glycan: the anti-inflammatory activity of sialylated IgG Fcs. Journal of clinical immunology 30 Suppl 1, S9–14, doi: 10.1007/s10875-010-9405-6 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maratha A. et al. Classical galactosaemia: novel insights in IgG N-glycosylation and N-glycan biosynthesis. Eur J Hum Genet, doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2015.254 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saldova R. et al. N-Glycosylation of Serum IgG and Total Glycoproteins in MAN1B1 Deficiency. J Proteome Res 14, 4402–4412, doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.5b00709 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold J. N., Wormald M. R., Sim R. B., Rudd P. M. & Dwek R. A. The impact of glycosylation on the biological function and structure of human immunoglobulins. Annu Rev Immunol 25, 21–50, doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141702 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Bovenkamp F. S., Hafkenscheid L., Rispens T. & Rombouts Y. The Emerging Importance of IgG Fab Glycosylation in Immunity. J Immunol 196, 1435–1441, doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1502136 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki H. et al. IgA1-secreting cell lines from patients with IgA nephropathy produce aberrantly glycosylated IgA1. J Clin Invest 118, 629–639, doi: 10.1172/JCI33189 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy C. et al. The role and importance of glycosylation of acute phase proteins with focus on alpha-1 antitrypsin in acute and chronic inflammatory conditions. J Proteome Res 13, 3131–3143, doi: 10.1021/pr500146y (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey E. & Rudd P. M. Acute phase glycoproteins: bystanders or participants in carcinogenesis? Ann N Y Acad Sci 1253, 122–132, doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06420.x (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stibler H. Carbohydrate-deficient transferrin in serum: a new marker of potentially harmful alcohol consumption reviewed. Clinical chemistry 37, 2029–2037 (1991). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peter J. et al. Identification of carbohydrate deficient transferrin forms by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry and lectin ELISABiochim Biophys Acta 1998 Aug 24;1381(3):356. Biochimica et biophysica acta 1380, 93–101 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grünewald S., Schollen E., Van Schaftingen E., Jaeken J. & Matthijs G. High residual activity of PMM2 in patients’ fibroblasts: possible pitfall in the diagnosis of CDG-Ia (phosphomannomutase deficiency). Am J Hum Genet 68, 347–354, doi: 10.1086/318199 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleiner D. E. et al. Design and validation of a histological scoring system for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 41, 1313–1321, doi: 10.1002/hep.20701 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong Q. et al. A Method for Comprehensive Glycosite-Mapping and Direct Quantitation of Serum Glycoproteins. J Proteome Res 14, 5179–5192, doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.5b00756 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satomi Y., Shimonishi Y. & Takao T. N-glycosylation at Asn(491) in the Asn-Xaa-Cys motif of human transferrin. FEBS letters 576, 51–56, doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.08.061 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morell A. G., Gregoriadis G., Scheinberg, I. H., Hickman J. & Ashwell G. The role of sialic acid in determining the survival of glycoproteins in the circulation. J Biol Chem 246, 1461–1467 (1971). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanda Y. et al. Comparison of biological activity among nonfucosylated therapeutic IgG1 antibodies with three different N-linked Fc oligosaccharides: the high-mannose, hybrid, and complex types. Glycobiology 17, 104–118, doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwl057 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng K., Bantog C. & Bayer R. The impact of glycosylation on monoclonal antibody conformation and stability. mAbs 3, 568–576, doi: 10.4161/mabs.3.6.17922 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupre T. et al. Defect in N-glycosylation of proteins is tissue-dependent in congenital disorders of glycosylation Ia. Glycobiology 10, 1277–1281 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pompach P. et al. Site-specific glycoforms of haptoglobin in liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Cell Proteomics 12, 1281–1293, doi: 10.1074/mcp.M112.023259 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J. et al. Analysis of serum haptoglobin fucosylation in hepatocellular carcinoma and liver cirrhosis of different etiologies. J Proteome Res 13, 2986–2997, doi: 10.1021/pr500128t (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weltman M. D., Farrell G. C., Hall P., Ingelman-Sundberg M. & Liddle C. Hepatic cytochrome P450 2E1 is increased in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology 27, 128–133, doi: 10.1002/hep.510270121 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamada Y. et al. Serum Fucosylated Haptoglobin as a Novel Diagnostic Biomarker for Predicting Hepatocyte Ballooning and Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. PLoS One 8, e66328, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066328 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamada Y. et al. A novel noninvasive diagnostic method for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis using two glycobiomarkers. Hepatology 62, 1433–1443, doi: 10.1002/hep.28002 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLean B. et al. Skyline: an open source document editor for creating and analyzing targeted proteomics experiments. Bioinformatics 26, 966–968, doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq054 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.