Abstract

Background

Performing a test of cure (TOC) could demonstrate success or failure of antimicrobial treatment of Chlamydia trachomatis infection, but recommendations for the timing of a TOC using nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) are inconsistent. We assessed time to clearance of C. trachomatis after treatment, using modern RNA- and DNA-based NAATs.

Methods

We analysed data from patients with a C. trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae coinfection who visited the STI Clinic Amsterdam, The Netherlands, from March through October 2014. After treatment with ceftriaxone plus either azithromycin or doxycycline, patients self-collected anal, vaginal or urine samples during 28 consecutive days. Samples were analysed using an RNA-based NAAT (Aptima Combo 2) and a DNA-based NAAT (Cobas 4800 CT/NG). We defined clearance as three consecutive negative results, and defined “blips” as isolated positive results following clearance.

Results

We included 23 patients with C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae coinfection. All patients cleared C. trachomatis during follow-up, and we observed no reinfections. The median time to clearance (range) was 7 days (1–13) for RNA, and 6 days (1–15) for DNA. Ninety-five per cent of patients cleared RNA at day 13, and DNA at day 14. The risk of a blip after clearance was 4.4 % (RNA) and 1.7 % (DNA).

Conclusions

If a TOC for anogenital chlamydia is indicated, we recommend performing it at least 14 days after initiation of treatment, when using modern RNA- and DNA-based assays. A positive result shortly after 14 days probably indicates a blip, rather than a treatment failure or a reinfection.

Keywords: Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Antimicrobial resistance, Nucleic acid amplification test, Test of cure

Background

Chlamydia trachomatis is the most common bacterial sexually transmitted infection (STI) globally, leading to late sequelae like pelvic inflammatory disease and infertility [1, 2]. Currently, the first-choice treatment for anogenital chlamydia consists of a single 1000 mg dose of azithromycin, or 100 mg doxycycline twice daily for 7 days [3, 4]. No resistance of C. trachomatis to either of these drugs has been reported, and a recent randomized controlled trial suggested no inferiority of azithromycin (97 % effective) compared to doxycycline (100 % effective) in urogenital chlamydia infections [5]. However, some studies voice concern about the efficacy of azithromycin as first-choice treatment for anorectal chlamydia [6–9]. Persisting C. trachomatis infections could be detected by performing a test of cure (TOC) after treatment. Current chlamydia treatment guidelines recommend a TOC between 3 and 4 weeks after initiation of treatment, in certain patient groups or when symptoms persist [4, 7, 10]. However, up to 90 % of chlamydia infections are asymptomatic, which could lead to persisting infections remaining undetected [4, 11, 12]. Previous reports on the appropriate timing of a TOC using molecular methods are inconsistent, and show (intermittent) persistence of C. trachomatis nucleic acids between 0 and 42 % up to 51 days after treatment [9, 13–19]. Recently, we performed a prospective cohort study on time to clearance for N. gonorrhoeae, using modern RNA- and DNA-based nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) [20]. Thirty-seven per cent of the included patients were also coinfected with C. trachomatis. As this study has results of 28 consecutive days for both RNA and DNA, we evaluated the appropriate timing of TOC for anogenital C. trachomatis infections in these coinfected patients.

Methods

Study population and procedure

In a previously performed cohort study we included patients with anogenital N. gonorrhoeae infection, who visited the STI Outpatient Clinic in Amsterdam, The Netherlands, from March through October 2014 [20]. We collected follow-up data and samples for only one infected anatomical site. The Academic Medical Center Amsterdam medical ethics committee approved the original cohort study (NL45935.018.13), and all patients provided written informed consent. For the current analysis, only patients coinfected with C. trachomatis were included from the cohort.

All patients had received routine treatment for N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis coinfection, consisting of a single intramuscular dose of 500 mg ceftriaxone, plus one oral dose of azithromycin 1000 mg in case of urogenital infection, or doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for at least 7 days in case of anorectal infection. Participants self-collected urine, anal or vaginal NAAT samples: one for RNA-based and one for DNA-based NAAT. Samples were collected pre-treatment and subsequently daily for 28 consecutive days after treatment. We requested participants to abstain from sexual contact or use condoms, refrain from vaginal or rectal douching and keep a study diary. At the end-of-study visit (within 35 days of inclusion) a nurse collected samples from the designated anatomical site for both NAATs.

NAAT testing for C. trachomatis

Samples for the RNA-based NAAT were tested using the Aptima Combo 2 assay for C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae (Hologic, San Diego, California). Test sensitivity is 93–98 % and specificity is >99 % [21–23]. Equivocal results were retested using the Aptima CT assay (Hologic). We considered repeatedly equivocal results as positive and excluded samples with repeatedly invalid results.

Samples for DNA-based NAAT were tested using the Cobas 4800 CT/NG assay for C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae (Roche, Basel, Switzerland), and reported as either negative or positive with corresponding cycle threshold (Ct) value. Test sensitivity is 87–97 % and specificity is >99 % [22–24]. Pre-treatment samples with discrepant RNA and DNA results were retested, using the Aptima CT assay (Hologic) for RNA samples, and the Abbott RealTime CT/NG assay (Abbott, Abbott Park, Illinois) for DNA samples.

Statistical analysis

The primary endpoint, clearance of C. trachomatis using RNA- or DNA-based NAAT, was defined as three or more consecutive negative results following a positive result. We allowed one missing sample between the last positive and the first negative result. Reinfection was defined as positive test results on three or more consecutive days after clearance; tests had to be positive for both RNA and DNA on at least 1 day. To analyse differences we compared patients grouped by anatomical site using Chi-square, Fisher’s exact or Kruskal-Wallis testing. Time to clearance was analysed with Kaplan-Meier curves, log-rank testing and Cox regression analysis. If we could not determine the exact day of clearance due to missing samples, the patient was excluded from this analysis.

The secondary endpoint, intermittent presence of RNA or DNA (“blip”), was defined as a positive test following clearance, not due to reinfection. Only positive results after the three consecutive negative tests results, used to define clearance, were eligible as a blip. We used logistic regression with generalized estimated equation (GEE) models to identify characteristics associated with blips. All analyses were performed using Stata (version 13; StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

Results

Participants

Out of 462 patients with anogenital gonorrhoea diagnosed at our STI clinic from March through October 2014, 77 were included in the original cohort. Twenty-six patients (34 %) had a coinfection with C. trachomatis of whom three were lost to follow-up. The remaining 23 patients were included in the current analysis.

Baseline characteristics

We included nine women, all with endocervical infections, and 14 men, of whom seven had a urethral and seven a rectal infection; 71 % were men who have sex with men (MSM, Table 1). The median age was 24 years (interquartile range [IQR]: 20–35 years); women were significantly younger (median 20 years) compared to men (median 32 years, P < 0.001). Five men (22 %) were HIV-positive, and four (80 %) were on antiretroviral therapy, of whom three had CD4 + cell counts of ≥500 cells/mm3. A previous chlamydia infection was reported by 12 patients (52 %), and 13 (57 %) currently experienced symptoms. The median time between diagnosis and inclusion was 8 days (range 0–12). At inclusion 16 patients (70 %) received ceftriaxone with azithromycin, and seven (30 %) received ceftriaxone with doxycycline.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of 23 patients with Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae coinfection at inclusion

| Characteristics | Total N (%)a |

Urethra N (%)a |

Rectum N (%)a |

Endocervix N (%)a |

P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 23 | 7 (30.4) | 7 (30.4) | 9 (39.1) | |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 14 (60.9) | 7 (100.0) | 7 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Female | 9 (39.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (100.0) | |

| Median age, in years (IQR) | 24 (20–35) | 29 (24–35) | 40 (24–44) | 20 (19–23) | 0.003 |

| Ethnicity | 1.00 | ||||

| Dutch | 11 (47.8) | 3 (42.9) | 4 (57.1) | 4 (44.4) | |

| Non-Dutch | 12 (52.2) | 4 (57.1) | 3 (42.9) | 5 (55.6) | |

| Sexual risk group | |||||

| MSM | 10 (43.5) | 3 (42.9) | 7 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Hetero male | 4 (17.4) | 4 (57.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Female | 9 (39.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (100.0) | |

| HIV positive | 5 (21.7) | 1 (14.3) | 4 (57.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0.02 |

| Using cART | 4 (80.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (100.0) | - | 0.20 |

| CD4 + cell count (cells/mm3) | 1.00 | ||||

| 350–499 | 1 (20.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (25.0) | - | |

| ≥ 500 | 4 (80.0) | 1 (100.0) | 3 (75.0) | - | |

| Previous chlamydia episode | 12 (52.2) | 3 (42.9) | 4 (57.1) | 5 (55.6) | 1.00 |

| Chlamydia in preceding 6 months | 3 (13.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (14.3) | 2 (22.2) | 0.75 |

| Symptoms or signs at examinationb,c | 13 (56.5) | 6 (85.7) | 3 (42.9) | 4 (44.4) | 0.23 |

| Median time to inclusion, days (IQR) | 8 (0–12) | 0 (0–0) | 10 (7–13) | 9 (8–12) | 0.003 |

| Treatment at inclusiond | 0.001 | ||||

| Ceftriaxone + azithromycin | 16 (69.6) | 7 (100.0) | 1 (14.3) | 8 (88.9) | |

| Ceftriaxone + doxycycline | 7 (30.4) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (85.7) | 1 (11.1) | |

IQR interquartile range, MSM men who have sex with men, HIV human immunodeficiency virus, cART combination antiretroviral therapy

aUnless otherwise indicated

bSymptoms included: discharge, itch, burning, frequent or painful urination, bleeding, abdominal pain, pain during sex, anal cramps or pain, and changed defecation

cSigns included: red urethra, discharge, bleeding, fragile mucosa, swelling or anal ulcerations

d1 patient was negative for Chlamydia trachomatis at the initial visit and therefore received ceftriaxone mono-therapy. The test at inclusion was positive and doxycycline was started 6 days after inclusion; therefore the start of the study for the C. trachomatis analysis in this patient was day 6, and the treatment was ceftriaxone + doxycycline

Behaviour after inclusion

The median number of collected samples was 28 (range 25–28, Table 2). Forty-eight per cent of patients missed at least one sample. Rectal or vaginal douching was reported by four of 16 patients with rectal or endocervical chlamydia (25 %). Sexual contact at some point during the 28 days of follow-up was reported by 12 patients (52 %), and condomless sex by five patients (22 %).

Table 2.

Behaviour after inclusion and clearance of Chlamydia trachomatis based on RNA and DNA testing, by anatomical site

| Characteristics | Total n (%)a |

Urethra n (%)a |

Rectum n (%)a |

Endocervix n (%)a |

P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | 23 | 7 (30.4) | 7 (30.4) | 9 (39.1) | |

| Behaviour after inclusion | |||||

| Median no. of samples collected (range) | 28 (25–28) | 28 (26–28) | 28 (26–28) | 27 (25–28) | 0.01 |

| Patients with missed samples | 11 (47.8) | 1 (14.3) | 2 (28.6) | 8 (88.9) | 0.009 |

| Median no. of missed samples (IQR) | 1 (1–3) | 2 (2–2) | 1.5 (1–2) | 1 (1–3) | 0.86 |

| Rectal/vaginal douching | 4 (25.0)g | - | 3 (42.9) | 1 (11.1) | 0.26 |

| Sexual contact | 12 (52.2) | 3 (42.9) | 4 (57.1) | 5 (55.6) | 1.00 |

| Condomless sex | 5 (21.7) | 1 (14.3) | 2 (28.6) | 2 (22.2) | 1.00 |

| RNA clearanceb | |||||

| Clearance during follow-up | 23 (100.0) | 7 (100.0) | 7 (100.0) | 9 (100.0) | |

| Day of clearance definablec | 21 (91.3) | 7 (100.0) | 6 (85.7) | 8 (88.9) | 1.00 |

| Median time to clearance, days (range) | 7 (1–13) | 5 (1–13) | 6.5 (5–9) | 8 (6–13) | 0.20 |

| Blipsd | |||||

| Samples at risk for blip | 411 | 140 | 126 | 145 | |

| Number of blips | 18 | 0 | 12 | 6 | |

| Number of patients | 8 (34.8) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (42.9) | 5 (55.6) | 0.09 |

| Median time to first blip from being at risk, days (range) | 1 (1–16) | - | 1 (1–2) | 4.5 (1–16) | 0.61 |

| DNA clearanceb,e | |||||

| Clearance during follow-up | 22 (100.0) | 6 (100.0) | 7 (100.0) | 9 (100.0) | |

| Day of clearance definablef | 21 (95.5) | 6 (100.0) | 7 (100.0) | 8 (88.9) | |

| Median time to clearance, days (range) | 6 (1–15) | 6 (1–14) | 5 (2–9) | 7.5 (5–15) | 0.08 |

| Blipsf | |||||

| Samples at risk for blip | 403 | 117 | 138 | 144 | |

| Number of blips | 7 | 0 | 0 | 7 | |

| Number of patients | 5 (22.7) | 0 | 0 | 5 (55.6) | 0.01 |

| Median time to first blip from being at risk, days (range) | 3 (2–8) | - | - | 3 (2–8) | |

| Mean Ct-value (range) | 38.6 (35.3–41.7) | - | - | 38.6 (35.3–41.7) | |

RNA ribonucleic acid, DNA deoxyribonucleic acid; IQR inter-quartile range; Ct cycle threshold

aUnless otherwise indicated

bBased on a definition of 3 consecutive negative tests following a positive test

cFor 2 patients the exact day of clearance could not be defined due to missing samples in the period of clearance

dBlip was defined as a positive test following clearance. Samples from all 23 patients were included; for those without an exact day of clearance due to missing samples, all samples after the first three consecutive negative results were considered at risk for blips

eOne patient was excluded from this analysis because the sample at inclusion was negative for Chlamydia trachomatis DNA

fFor 1 patient the exact day of clearance could not be defined due to missing samples in the period of clearance

gRectal/vaginal douching was only reported on by the 16 patients with rectal/endocervical infection

Clearance of C. trachomatis RNA and DNA

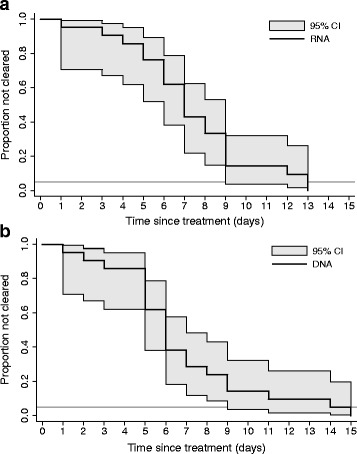

During the 28 days of follow-up all patients cleared C. trachomatis RNA, and none experienced a reinfection (Table 2). Because of missing samples in the days around clearance, we could not determine the exact day of clearance for two patients. The median time to clearance for the remaining 21 patients was 7 days (range 1–13), and 95 % of patients had cleared RNA at day 13 (Fig. 1a). One patient was post-hoc excluded from the DNA analysis because of a negative pre-treatment DNA result for C. trachomatis. All other patients cleared C. trachomatis DNA during follow-up, and there were no reinfections. We could not determine the exact day of clearance for one patient (Table 2). The median time to clearance of the 21 patients was 6 days (range 1–15), and 95 % of patients had cleared DNA at day 14 (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

Time to clearance of Chlamydia trachomatis RNA (a) and DNA (b). The horizontal line represents 95 % clearance. RNA, ribonucleic acid; DNA, deoxyribonucleic acid

Because of the small sample size the power to detect associations with clearance is very limited. Cox regression analyses showed no significant associations with clearance, and Kaplan-Meier curves with log-rank testing showed no significant difference in clearance by anatomical site or treatment.

Blips after clearance of C. trachomatis

After clearance of RNA, eight patients experienced 18 blips (Table 2). After clearance of DNA, five patients experienced seven blips, of which three (all vaginal samples) coincided with RNA blips (Table 2). Among the patients with blips, sex after clearance was reported by five (RNA) and three (DNA) patients. We observed both RNA and DNA blips among vaginal samples, while we observed only RNA blips among rectal samples, and no blips among urine samples.

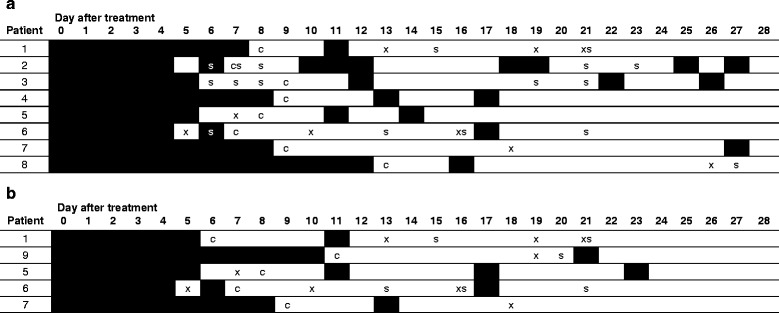

When analysing all samples after clearance (411 for RNA and 403 for DNA), the median number of days at risk per patient was 19 (range 12–25) for RNA, and 20 (range 11–25) for DNA. The overall risk of finding a blip after clearance was 4.4 % per day for RNA and 1.7 % per day for DNA. DNA blips had significantly higher Ct-values (mean: 38.6, range: 35.3–41.7) compared to pre-treatment samples (mean: 31.6, range: 27.8–39.3, P < 0.001). Only two RNA blips and two DNA blips were observed within 24 h of reported sex, of which one was a blip in both RNA and DNA testing (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Test results, reported sexual contact and blips of Chlamydia trachomatis RNA (a) or DNA (b) per day of follow-up after treatment in patients with blips. Black squares: positive for C. trachomatis (before clearance, or blip); white squares: negative for C. trachomatis; c: clearance; x: missing sample; s: sexual contact reported on this day (after sampling)

Although the sample size was relatively small, we determined characteristics associated with blips using GEE logistic regression. RNA blips were significantly associated with HIV-positivity (odds ratio [OR]: 8.0, 95 % confidence interval [95 %-CI]: 2.3–28.1, P = 0.001), a chlamydia infection in the previous 6 months (OR: 6.6, 95 %-CI: 1.8–24.7, P = 0.005), and with absence of symptoms or signs (OR: 0.17, 95 %-CI: 0.03–0.97, P = 0.05). In multivariable analysis, HIV-status and previous chlamydia infection remained significantly associated (OR: 7.1, 95 %-CI: 2.5–19.9, P < 0.001, and OR: 5.9, 95 %-CI: 2.2–16.3, P = 0.001, respectively). As there were seven DNA blips, the power for this analysis was limited; only sexual contact in the 24 h before sampling was significantly associated in univariable analysis (OR: 6.8, 95 %-CI: 1.3–36.7, P = 0.03).

Discussion

In this study we analysed the time to clearance of anogenital C. trachomatis after treatment in patients coinfected with N. gonorrhoeae, using modern RNA- and DNA-based NAATs and daily collected samples. The median time to clearance was 7 days for RNA and 6 days for DNA. Ninety-five per cent of patients had cleared C. trachomatis RNA and DNA after 13 and 14 days, respectively.

Several previous studies reported on in vivo clearance of C. trachomatis after treatment, but used different molecular testing methods, and a sampling frequency of no more than twice a week. Some studies observed clearance of DNA within 3 weeks using ligase chain reaction or in-house PCR methods [13, 14], while other studies reported 5–25 % DNA persistence after 3–4 weeks [9, 15, 16, 25]. The exact time to clearance of RNA, when tested by NAAT, was also previously unknown. Sena et al. reported 12 % RNA persistence after 4 weeks in men, while Dukers et al. reported 42 % intermittent positive results up to 51 days [9, 19]. In addition, a recent study reported 24 % positivity in 180 patients after 6 months, but no data on re-exposure or reinfections were reported [26]. Since none of these previous studies reported results from consecutive days, the exact time to clearance could not be determined, and prolonged persistence could not be distinguished from blips. In addition, none reported data on events that could have caused reinfection, like was done in the current study. Although no previous studies have been performed on the clearance of C. trachomatis in patients coinfected with N. gonorrhoeae, our results confirm the assumption that C. trachomatis RNA and DNA are cleared after 2 weeks [14, 17, 25].

Intermittent positive results or blips have been previously described by several studies; between 5 and 18 % of patients had a positive test result following a previous negative result after treatment [9, 14, 17–19]. We report an overall risk of blips after clearance of almost 2 % for DNA and 4 % for RNA, and no treatment failures or reinfections. The slightly higher sensitivity of the RNA test could explain the higher frequency of RNA blips, compared to DNA blips. The fact that all but one of the pre-treatment samples initially diagnosed by RNA testing were also positive for DNA, makes it unlikely that the different sensitivity is of clinical importance in diagnosing chlamydia. On the other hand, when performing a TOC, higher sensitivity could result in more positive results. The implications of this should be clarified in larger studies. Unfortunately, NAAT testing only gives information about the presence of genetic material, but not on the viability of the pathogen or whether this is still infectious. Therefore blips could be the result of deposition of viable or non-viable genetic material by a sexual partner, release of genetic material by degrading cells, or possibly the presence of elementary bodies that hold genetic components of C. trachomatis [18, 27]. The origin of blips needs to be further examined in future research. Due to the small sample size we could not identify characteristics associated with the occurrence of blips. However, the occurrence of blips, as well as reinfections, could explain the higher positivity rates reported by some studies, especially in those with very long follow-up and limited sampling [9, 15, 18, 19, 26].

Our study has several limitations. It was performed at a single centre in a high-incidence population, which may limit the generalizability. We selected patients from a cohort infected with N. gonorrhoeae, so this concerns a population coinfected with N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis, which may influence both time to clearance and the occurrence of blips. Because all patients were coinfected with N. gonorrhoeae, they were also treated with ceftriaxone. Since ceftriaxone is not effective against chlamydia, it is unlikely that treatment with ceftriaxone influenced the clearance of C. trachomatis. Nevertheless, confirmation of our results in chlamydia monoinfected patients is warranted.

Conclusions

Our results are the first to show that C. trachomatis RNA and DNA are cleared within 14 days of initiating treatment, using daily testing. Despite the small sample size, our results suggest that if a TOC is indicated in patients with C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae coinfection, it is best performed after at least 2 weeks. Positive results obtained more than 2 weeks after initiation of treatment should be evaluated carefully, as these probably represent blips, and do not necessarily indicate treatment failure or reinfection. To exclude blips as the cause of a positive TOC, we recommend to obtain a new sample for retesting.

Acknowledgments

We thank all participants of the cohort for their effort. We also thank Myra van Leeuwen, Claudia Owusu and Princella Felipa for their assistance in recruiting the participants. We thank Fred Zethof for performing the Aptima Combo 2 assays, Davy Janssen for performing the Cobas 4800 assays and Paul Smits for performing the Abbott NG/CT assays.

Funding

This study was funded by the Public Health Service Amsterdam.

Availability of data and materials

Due to the small sample size and possible identification of patients the data are not openly available. Data are available by request to the corresponding author.

Authors’ contributions

CMW, MFSL, MU, APD and HJCV designed the study. CMW coordinated the study implementation, included patients and collected samples. APD and RS supervised the laboratory testing. CMW analysed the data. MFSL provided statistical advice for the data analysis. All authors interpreted the data. CMW wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version.

Competing interests

Hologic provided Aptima test materials and kits in kind. Roche provided Cobas test materials and kits in kind.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Academic Medical Center Amsterdam medical ethics committee approved the original cohort study (NL45935.018.13), and all patients provided written informed consent.

Abbreviations

- 95 %-CI

95 % confidence interval

- Ct

Cycle threshold

- DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid

- GEE

Generalized estimated equation

- HIV

Human immunodeficiency virus

- IQR

Interquartile range

- MSM

Men who have sex with men

- NAAT

Nucleic acid amplification test

- OR

Odds ratio

- PCR

Polymerase chain reaction

- RNA

Ribonucleic acid

- STI

Sexually transmitted infection

- TOC

Test of cure

Contributor Information

Carolien M. Wind, Email: cwind@ggd.amsterdam.nl

Maarten F. Schim van der Loeff, Email: mschimvdloeff@ggd.amsterdam.nl

Magnus Unemo, Email: magnus.unemo@regionorebrolan.se.

Rob Schuurman, Email: R.Schuurman-1@umcutrecht.nl.

Alje P. van Dam, Email: avdam@ggd.amsterdam.nl

Henry J. C. de Vries, Phone: +31 205555429, Email: h.j.devries@amc.uva.nl

References

- 1.Newman L, Rowley J, Vander HS, Wijesooriya NS, Unemo M, Low N, et al. Global estimates of the prevalence and incidence of four curable sexually transmitted infections in 2012 based on systematic review and global reporting. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0143304. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control . Annual Epidemiological Report 2014 - Sexually Transmitted Infections, Including HIV and Blood-Borne Viruses. Stockholm: ECDC; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64(No. RR-3):1–137. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lanjouw E, Ouburg S, de Vries HJ, Stary A, Radcliffe K, Unemo M. 2015 European guideline on the management of Chlamydia trachomatis infections. Int J STD AIDS Published (Online first) 24 november 2015. doi: 10.1177/0956462415618837. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Geisler WM, Uniyal A, Lee JY, Lensing SY, Johnson S, Perry RC, et al. Azithromycin versus Doxycycline for Urogenital Chlamydia trachomatis Infection. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2512–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1502599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hocking JS, Kong FY, Timms P, Huston WM, Tabrizi SN. Treatment of rectal chlamydia infection may be more complicated than we originally thought. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70:961–4. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horner PJ. Azithromycin antimicrobial resistance and genital Chlamydia trachomatis infection: duration of therapy may be the key to improving efficacy. Sex Transm Infect. 2012;88:154–6. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2011-050385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kong FY, Hocking JS. Treatment challenges for urogenital and anorectal Chlamydia trachomatis. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:293. doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-1030-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dukers-Muijrers NH, Morre SA, Speksnijder A, van der Sande MA, Hoebe CJ. Chlamydia trachomatis test-of-cure cannot be based on a single highly sensitive laboratory test taken at least 3 weeks after treatment. PLoS One. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geisler WM. Diagnosis and Management of Uncomplicated Chlamydia trachomatis Infections in Adolescents and Adults: Summary of Evidence Reviewed for the 2015 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(Suppl 8):S774–84. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rebe K, Lewis D, Myer L, de Swardt G, Struthers H, Kamkuemah M, et al. A cross sectional analysis of Gonococcal and chlamydial infections among Men-Who-have-Sex-with-Men in Cape Town, South Africa. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0138315. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tongtoyai J, Todd CS, Chonwattana W, Pattanasin S, Chaikummao S, Varangrat A, et al. Prevalence and correlates of chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae by anatomic site among urban Thai Men Who have Sex with Men. Sex Transm Dis. 2015;42:440–9. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Claas HC, Wagenvoort JH, Niesters HG, Tio TT, Van Rijsoort-Vos JH, Quint WG. Diagnostic value of the polymerase chain reaction for Chlamydia detection as determined in a follow-up study. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:42–5. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.1.42-45.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gaydos CA, Crotchfelt KA, Howell MR, Kralian S, Hauptman P, Quinn TC. Molecular amplification assays to detect chlamydial infections in urine specimens from high school female students and to monitor the persistence of chlamydial DNA after therapy. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:417–24. doi: 10.1086/514207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morre SA, Sillekens PT, Jacobs MV, de Blok S, Ossewaarde JM, van Aarle P, et al. Monitoring of Chlamydia trachomatis infections after antibiotic treatment using RNA detection by nucleic acid sequence based amplification. Mol Pathol. 1998;51:149–54. doi: 10.1136/mp.51.3.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whittington WL, Kent C, Kissinger P, Oh MK, Fortenberry JD, Hillis SE, et al. Determinants of persistent and recurrent Chlamydia trachomatis infection in young women: results of a multicenter cohort study. Sex Transm Dis. 2001;28:117–23. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200102000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jang D, Sellors J, Howard M, Mahony J, Frost E, Patrick D, et al. Correlation between culture testing of swabs and ligase chain reaction of first void urine from patients recently treated for Chlamydia trachomatis. Sex Transm Infect. 2003;79:237–9. doi: 10.1136/sti.79.3.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Renault CA, Israelski DM, Levy V, Fujikawa BK, Kellogg TA, Klausner JD. Time to clearance of Chlamydia trachomatis ribosomal RNA in women treated for chlamydial infection. Sex Health. 2011;8:69–73. doi: 10.1071/SH10030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sena AC, Lensing S, Rompalo A, Taylor SN, Martin DH, Lopez LM, et al. Chlamydia trachomatis, Mycoplasma genitalium, and Trichomonas vaginalis infections in men with nongonococcal urethritis: predictors and persistence after therapy. J Infect Dis. 2012;206:357–65. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wind CM, Schim van der Loeff MF, Unemo M, Schuurman R, van Dam AP, de Vries HJC. Test of cure for anogenital gonorrhoea using modern RNA-based and DNA-based nucleic acid amplification tests - a prospective cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62:1348-55. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Schachter J, Moncada J, Liska S, Shayevich C, Klausner JD. Nucleic acid amplification tests in the diagnosis of chlamydial and gonococcal infections of the oropharynx and rectum in men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35:637–42. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31817bdd7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Der Pol B, Liesenfeld O, Williams JA, Taylor SN, Lillis RA, Body BA, et al. Performance of the cobas CT/NG test compared to the Aptima AC2 and Viper CTQ/GCQ assays for detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:2244–9. doi: 10.1128/JCM.06481-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taylor SN, Liesenfeld O, Lillis RA, Body BA, Nye M, Williams J, et al. Evaluation of the Roche cobas(R) CT/NG test for detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae in male urine. Sex Transm Dis. 2012;39:543–9. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31824e26ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Geelen TH, Rossen JW, Beerens AM, Poort L, Morre SA, Ritmeester WS, et al. Performance of cobas(R) 4800 and m2000 real-time assays for detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae in rectal and self-collected vaginal specimen. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013;77:101–5. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2013.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hillis SD, Coles FB, Litchfield B, Black CM, Mojica B, Schmitt K, et al. Doxycycline and azithromycin for prevention of chlamydial persistence or recurrence one month after treatment in women. A use-effectiveness study in public health settings. Sex Transm Dis. 1998;25:5–11. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199801000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kapil R, Press CG, Hwang ML, Brown L, Geisler WM. Investigating the epidemiology of repeat Chlamydia trachomatis detection after treatment by using C. trachomatis OmpA genotyping. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53:546–9. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02483-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bragina EY, Gomberg MA, Dmitriev GA. Electron microscopic evidence of persistent chlamydial infection following treatment. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:405–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2001.00342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Due to the small sample size and possible identification of patients the data are not openly available. Data are available by request to the corresponding author.